Abstract

Although polychlorinated biphenyl (PCBs) production, and new uses for PCBs, was halted in the 1970s in the United States, PCBs continue to be used in closed systems and persist in the environment, accumulating in fatty tissues. PCBs are efficacious inducers of drug metabolism and may increase oxidative events and alter many other biochemical and morphologic parameters within cells and tissues. The goal of the present study was to evaluate the effects of a single, very low dose of PCB 126 (3,3′,4,4′,5-pentachlorobiphenyl), a coplanar, dioxin-like PCB congener and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) agonist, on the redox status, metals homeostasis, antioxidant enzymes, and cellular morphology. To examine these parameters, male Sprague-Dawley rats were fed a purified AIN-93 basal diet containing 0.2 ppm selenium for two weeks, then administered a single i.p. injection of corn oil (5 ml/kg body weight) or 1 μmol PCB 126/kg body weight (326 μg/kg body weight) in corn oil. Rats were maintained on the diet for an additional two weeks before being euthanized. This dose of PCB 126 did not later feed intake or growth, but significantly increased liver weight (42%) and hepatic microsomal cytochrome P-450 (CYP1A) enzyme activities (10–40-fold increase). Hepatic zinc, selenium, and glutathione levels were significantly decreased 15%, 30%, and 20%, respectively, by PCB 126. These changes were accompanied by a 25% decrease in selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase activity. In contrast, hepatic copper levels were increased 40% by PCB 126. PCB 126-induced pathology was characterized by hepatocellular hypertrophy and mild steatosis in the liver and a mild decrease in cortical T-cells in the thymus. This controlled study in rats fed a purified diet shows that even a single, very low dose of PCB 126 that did not alter feed intake or growth, significantly perturbed redox and metals homeostasis and antioxidant and enzyme levels in rodent liver.

Keywords: Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs), Glutathione, Redox Status, Selenium, Copper, Zinc

1. Introduction

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were commercially manufactured as industrial mixtures that were known for their stability under a broad range of chemical, thermal, and electrical conditions (Safe 1994). Although production of these chemicals was halted in the 1970s, their resistance to breakdown and their lipophilicity allows them to biomagnify in the food chain and persist in the environment (Hansen 1987).

Among the 209 possible PCB congeners, biological and chemical properties vary greatly depending on the number and placement of chlorine atoms on the biphenyl ring (Ludewig et al. 2007). Especially higher chlorinated PCBs selectively induce cytochrome P-450 monooxygenases (Parkinson et al. 1983) that catalyze the oxidation of a broad range of endogenous and exogenous substances. Congeners with no chlorine atoms adjacent to the biphenyl bridge (in positions 2, 2 ′, 6, 6′) may assume a more co-planar configuration and are known as dioxin-like PCBs because of their ability to mimic 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) and bind to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) (Bandiera et al. 1982). Dioxin-like PCBs, such as PCB 126, that are potent AhR agonists, induce cytochrome P-450 (CYP) 1A proteins which may also result in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) via an uncoupling of the catalytic cycle of cytochrome P-450, resulting in a partial reduction of oxygen (Lewis and Pratt 1998; Schlezinger et al. 1999). The avid binding of PCB 126 to the AhR is reflected in its Toxic Equivalency Factor (TEF) of 0.1 relative to that of TCDD of 1.0 (Van den Berg et al. 1998; Yoshizawa et al. 2007).

Selenium (Se), an essential trace element in the antioxidant defense system, is encoded into selenocysteine, an amino acid incorporated into a key antioxidant enzyme, the Se-dependent form of glutathione peroxidase (SeGPx). SeGPx plays an important role in detoxifying lipid peroxidation-forming hydrogen peroxides, and loss of SeGPx has been shown to be associated with increased oxidative stress (Condell and Tappel 1983; McCray et al. 1976; Muller and Pallauf 2002; Pohjanvirta et al. 1990). Schramm and others have reported that the PCB mixture Aroclor 1254, as well as certain congeneric PCBs, decrease the levels of SeGPx in rodent liver (Schramm et al. 1985). This decrease has been shown to be caused by coplanar chlorinated biphenyls, including PCB 77 and PCB 126 (Hori 1997). The decrease in SeGPx caused by PCB 77 is accompanied by a decrease in message RNA for the enzyme as well as a decrease in hepatic Se levels (Twaroski et al. 2001b). Thus, in addition to increasing the production of ROS, PCBs also decrease the antioxidant enzyme defenses that are capable of detoxifying the ROS. Therefore, one goal of this study was to identify indices as biomarkers of oxidative stress.

Here we examined the congener – specific toxicity of a dioxin-like PCB congener, PCB 126, by examining its ability to alter hepatic redox status. We hypothesized that a low dose of PCB 126 will disrupt glutathione and metals levels, antioxidant enzyme homeostasis, and increase oxidative stress. The dose selected (1 μmol/kg body weight) was chosen as a non-lethal dose that would maximally induce hepatic CYP 1A activities, while not altering the growth of the animals. A dose of PCB 126 in the rat of less than 1 μmol/kg body weight (275 μg/kg body weight) was able to maximally induce hepatic CYP1A, a level of activity that was maintained over 22 days time (Fisher et al. 2006).

2. Material & Methods

2.1. Chemicals

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated. PCB 126 (3,3′,4,4′,5-pentachlorobiphenyl) was prepared by an improved Suzuki-coupling method of 3,4,5-trichlorobromobenzene with 3,4-dichlorophenyl boronic acid utilizing a palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction (Luthe et al. 2009). The crude product was purified by aluminum oxide column and flash silica gel column chromatography and recrystallized from methanol. The final product purity was determined by GC-MS analysis to be >99.8% and its identity confirmed by 13C NMR. Caution: PCBs and their metabolites should be handled as hazardous compounds in accordance with NIH guidelines.

2.2. Animals

This animal experiment was conducted with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Iowa. Male Sprague Dawley rats (75–100g) (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, IN) were housed in hanging metal mesh cages in a controlled environment maintained at 22°C with a 12 hour light-dark cycle. Rats were fed a purified AIN-93 basal diet containing 0.2 ppm sodium selenate (Table 1; Harland Teklad, Madison, WI) and water ad libitum. A purified diet with a carefully controlled selenium level was chosen for this study, since previously we had observed that dietary selenium could directly influence the outcome of studies of the regulation of SeGPx (Chen et al. 1990). After two weeks on the diet, rats were administered a single i.p. injection of vehicle (stripped corn oil; Acros Chemical Company, Pittsburgh, PA) or vehicle with PCB 126 (1 μmol/kg body weight; 326 μg/kg body weight), and were euthanized 2 weeks later by carbon dioxide asphyxiation and cervical dislocation. Livers and other organs were excised and apportioned as follows:

Table 1.

AIN – 93 Diet Composition*

| Constituent | g/kg |

|---|---|

| Casein | 140.0 |

| L-Cysteine | 1.8 |

| Corn Starch | 465.692 |

| Maltodextrin | 155.0 |

| Sucrose | 99.88 |

| Soybean Oil | 40.0 |

| Cellulose | 50.0 |

| Mineral Mix, AIN-93-MX | 35.0 |

| Sodium Selenate (0.1% in sucrose) | 0.12 |

| Vitamin Mix, AIN-93-VX | 10.0 |

| Choline Bitartrate | 2.5 |

| TBHQ, antioxidant | 0.008 |

Se concentration in the diet was confirmed with ICP-MS as 0.21 ppm.

approximately 0.5 g liver was immediately homogenized in 5% 5-sulfosalicylic acid (5-SSA) (w/v) (Anderson et al. 1985; Meister and Anderson 1983) and was used for the determination of GSH and GSSG as described below.

representative slices of liver, spleen, and thymus were placed in 10% buffered formalin for histologic analysis as described below.

portions of liver and kidney, approximately 2.0 g, were taken and frozen in acid-washed high density polyethylene scintillation vials for metal analysis.

the remaining liver tissue was homogenized in ice-cold 0.25 M sucrose solution containing 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4. The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000g for 20 min. The resulting supernatant was then centrifuged at 100,000g for 1 h. The supernatant containing the cytosolic fractions were aliquoted. Microsomal pellets were resuspended in ice-cold sucrose/EDTA solution. Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Lowry et al. (1951).

2.3. Glutathione (GSH & GSSG) analysis

GSH and GSSG levels were determined in hepatic liver tissue by the methods of Griffith (1980) and Anderson (1985), based on an enzyme recycling assay using glutathione reductase, 5,5′-dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) and NADPH. Absorbance change at 412 nm was followed in a Beckman DU-670 spectrophotometer for 5 min. The rate of yellow color accumulation is the result of 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate (TNB) formed from DTNB. This rate is proportional to the amount of total glutathione in the sample. GSSG was measured independently by incubating the tissue in 2-vinylpuridine, which conjugates GSH prior to the measurement of the remaining GSSG. Reduced glutathione is determined by subtracting GSSG from total glutathione. GSH levels are expressed per mg protein.

2.4. Trace Elements determination

Metal concentrations in rat tissues were quantitatively determined by Inductively Coupled Plasma – Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). ICP-MS was selected due to its low detection limits and multi-element capacity (Entwisle and Hearn 2006). Liver tissue was acid-digested with HNO3 in a closed Teflon vessel in a CEM® MARS5 Microwave Digestion System prior to ICP-MS measurement. Metal concentrations in the digested samples were then determined in an Agilent 7500ce ICP-MS equipped with a CETAC AS520 auto sampler.

2.5. Histology

Formalin fixed tissues were processed routinely, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 3–4 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for light microscopic examination. Frozen sections of selected liver samples were stained with oil-red-O for the evaluation of lipids.

2.6. Measurement of CYP1A activity

Cytochrome P450 1A1 and 1A2 activities were estimated in hepatic microsomes by measuring the ethoxyresorufin deethylase (EROD) and methoxyresorufin demethylase (MROD) activity as previously reported (Burke and Mayer 1974). Briefly, using ethoxy- or methoxyresorufin as substrates, the monooxygenase reaction by CYP1A results in the formation of the fluorescent resorufin, which was detected spectrofluorometrically using an excitation wavelength of 550 nm and emission wavelength of 585 nm.

2.7. Measurement of GPx activities

The glutathione peroxidase activities in the cytosolic fraction were determined using the method of Lawrence and Burke (1976). Briefly, SeGPx and total GPx activities were determined using hydrogen peroxide and cumene hydroperoxide as the substrates, respectively. Absorbance change at 340 nm was followed in a Beckman DU-650 for 5 min. One unit of enzymatic activity is defined as the amount of protein that oxidizes 1 μM of NADPH per min, expressed as milliunits per mg protein.

2.8. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA to test for differences in treatment means. Treatment groups were considered statistically different at p < 0.001, 0.01, or 0.05.

3. Results

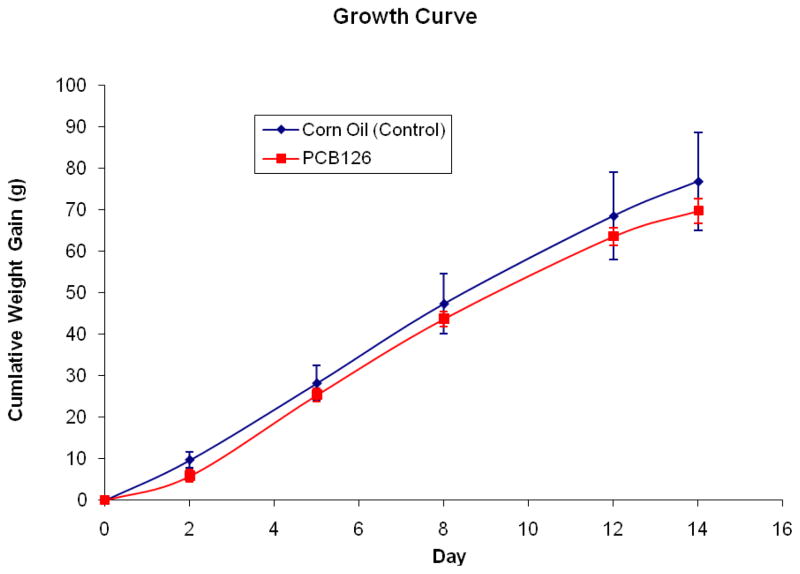

The growth rate of rats treated with PCB 126 did not differ significantly from that of vehicle – treated rats (Figure 1). However, at the termination of the feeding study, PCB 126 – treated rats showed significant increases in both absolute and relative liver weights (38% and 42%, respectively), while both absolute and relative thymus weights were decreased significantly (46% and 44%, respectively) (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Growth curve of vehicle- (control) and PCB 126-treated rats. Average weight of rats on injection day (day 0): Control, 184 ± 6.0g; PCB 126, 187 ± 4.0g. The growth of rats was not significantly affected by PCB 126 treatment.

Table 2.

Body Weight, Liver Weight, Thymus Weight, and Ratio

| Corn Oil | PCB 126 | |

|---|---|---|

| Final Body Weight (g) | 261 ± 8 | 254 ± 5 |

| Liver Weight (g) | 12.9 ± 0.6 | 17.9 ± 0.8** |

| Liver/Body Weight × 100(%) | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.2** |

| Thymus Weightm (g) | 0.59 ± 0.02 | 0.32 ± 0.01** |

| Thymus/Body Weight × 100 (%) | 0.227 ± 0.010 | 0.126 ± 0.004** |

Results are expressed as mean ± SE, n = 4 rats.

statistically significantly different compared to the vehicle control, p < 0.001

Glutathione levels in the liver were determined as indicators of oxidative stress. Hepatic levels of both oxidized (GSSG) and reduced glutathione (GSH) were reduced by 20% in PCB 126 – treated rats, relative to control levels, reflecting an overall decrease in hepatic total glutathione in the treated rats (Table 3), and a shift to a more oxidized environment.

Table 3.

GSH & GSSG

| Corn Oil | PCB 126 | |

|---|---|---|

| GSH nmoles/mg tissue | 7.44 ± 0.62 | 5.91 ± 0.32* |

| GSSG nmoles/mg tissue | 0.053 ± 0.002 | 0.041 ± 0.001** |

Results are mean ± SEM of GSH or GSSG/whole liver weight (nM/mg) with n = 6 rats. Means were statistically significantly different from vehicle control when

p < 0.05

p < 0.001.

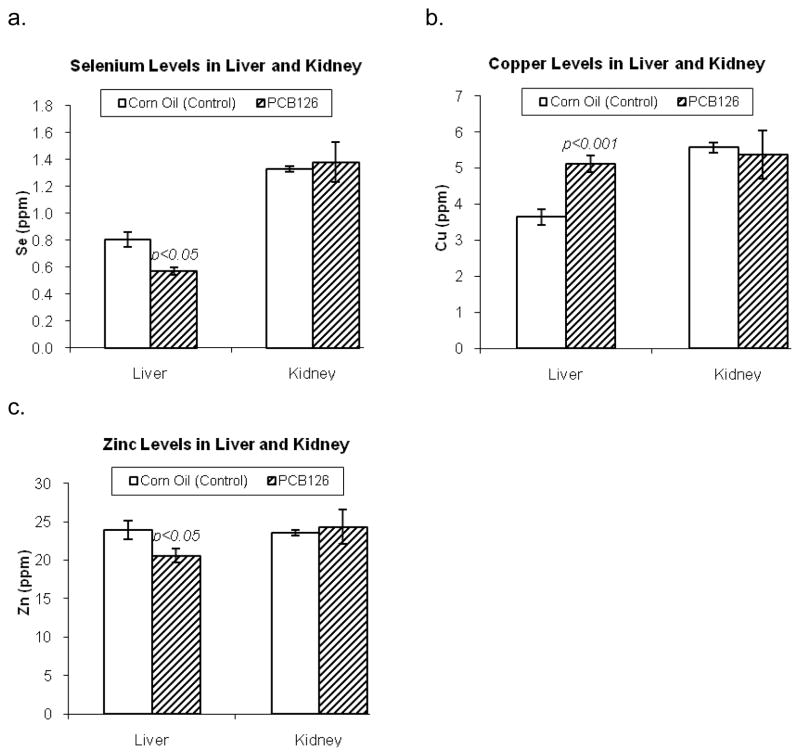

PCB 126 had a strong effect on trace metals in the liver, causing a 30% decrease in hepatic selenium levels and a 15% decrease in zinc levels (Figure 2). In contrast, copper levels were increased 40% in the livers of PCB 126 – treated rats (Figure 2). By comparison, no significant effects on the target metals selenium, copper and zinc were observed in the kidneys of PCB – treated rats.

Figure 2.

Liver and kidney selenium, copper, and zinc levels of vehicle- (control) and PCB 126 treated rats. Hepatic selenium and zinc were significantly diminished, copper increased in PCB 126 treated rats. Kidney levels were not significantly affected by PCB 126.

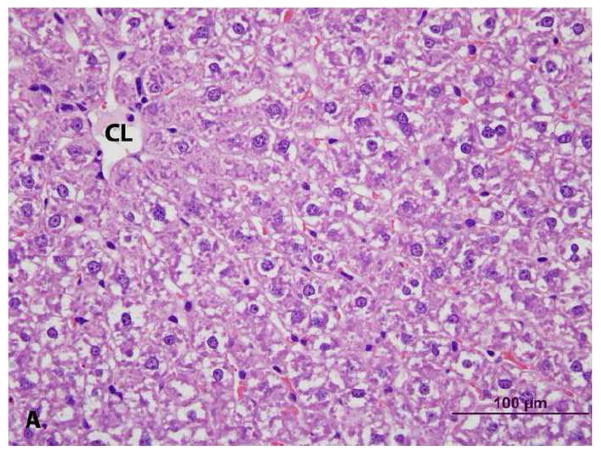

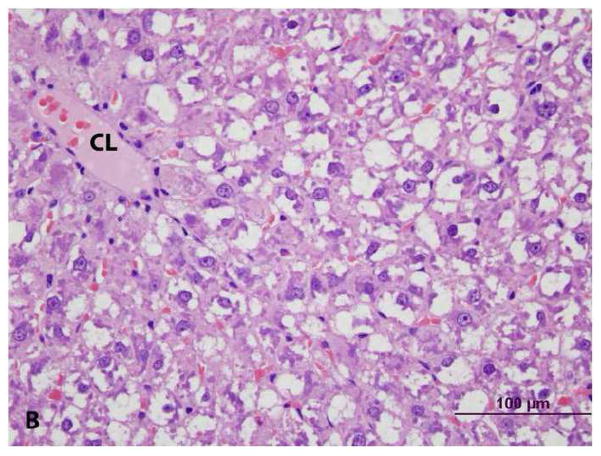

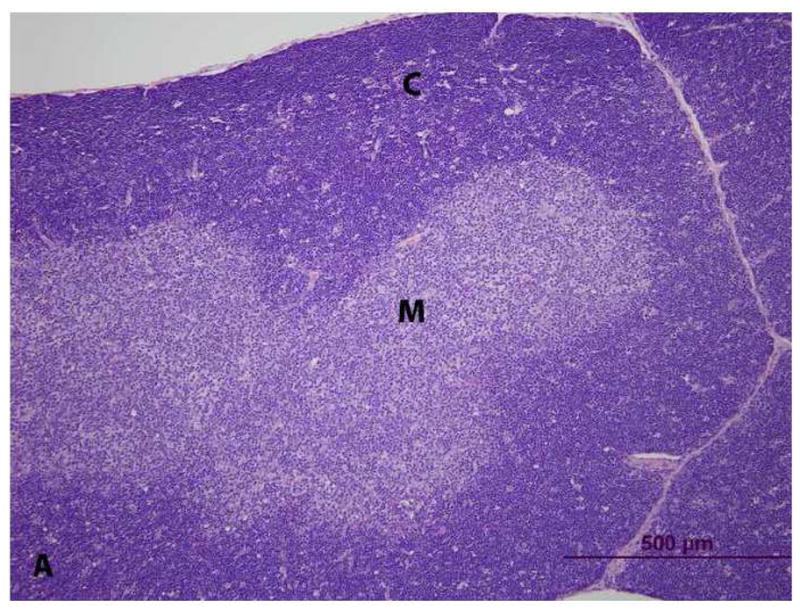

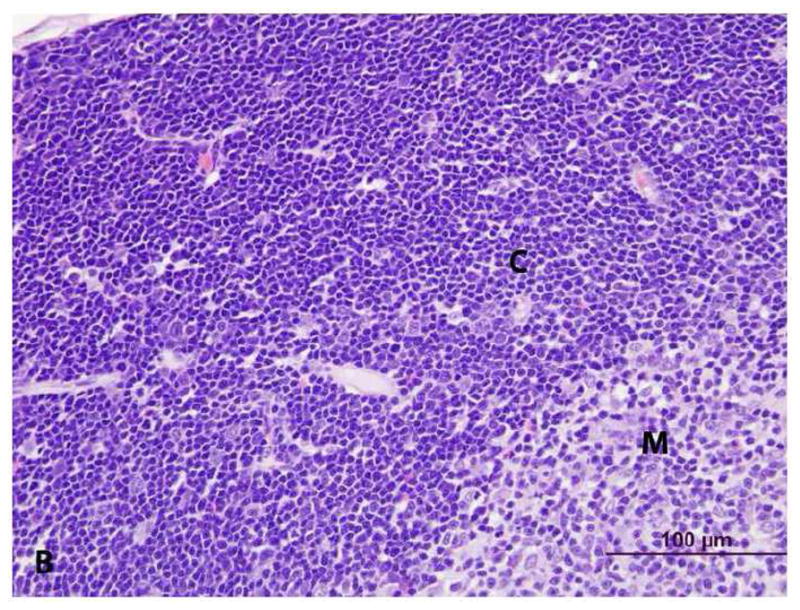

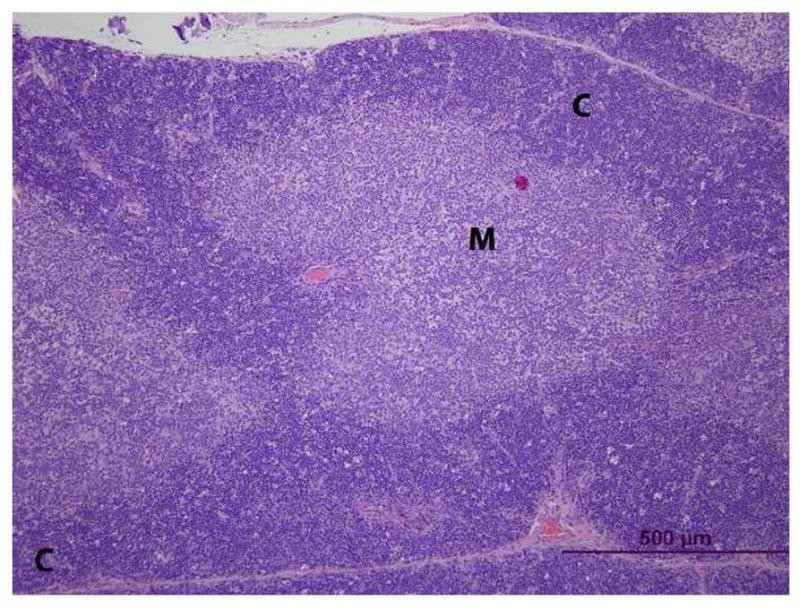

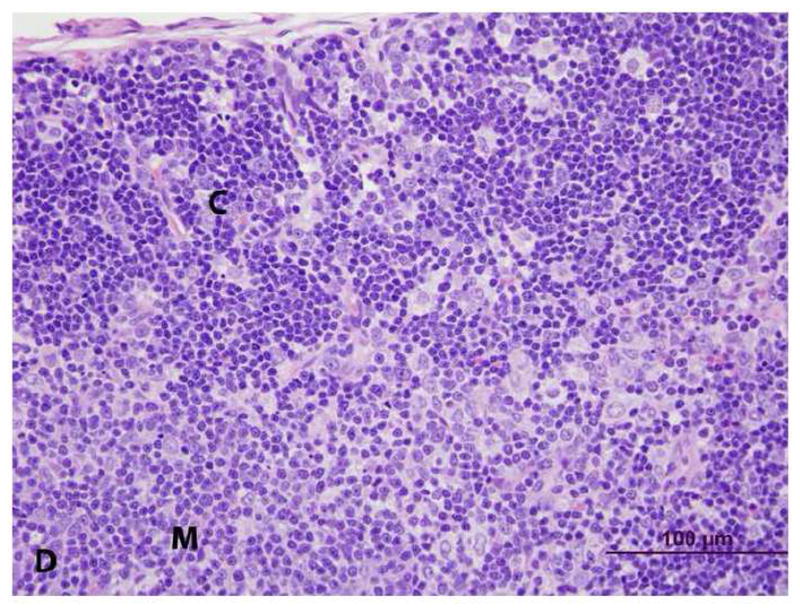

Histologic examination of livers indicated an increase in size of hepatic lobules due to hypertrophy (enlargement) of hepatocytes in PCB 126-treated rats; mild capsular irregularity was also present. Hepatocellular hypertrophy was characterized by large areas of cytoplasmic pallor (hydropic degeneration), small poorly defined vacuoles and occasional peripheralization of nuclei (Figures 3a & 3b). With oil-red-O stain, small lipid globules were present in hepatocytes (mild steatosis) from PCB 126-treated rats but virtually absent in controls (not shown). In addition, there was mild thymic atrophy in PCB 126-treated rats characterized by decreased cortical to medullary width (Figures 4a, 4b, 4c, & 4d). The cortex had decreased density of T-lymphocytes with scattered macrophages indicating T-lymphocyte apoptosis. No changes were observed in the spleens of PCB 126-treated rats (not shown).

Figure 3. Histopathology of liver from vehicle- (control) and PCB 126 treated rats. (CL = centrilobular vein) H&E stain.

A. Control. Mild cytoplasmic clearing without vacuolization and with centrally located nuclei, consistent with glycogen.

B. PCB 126. Hepatocellular hypertrophy characterized by large areas of cytoplasmic pallor (hydropic degeneration), poorly defined vacuoles (lipid) and occasional peripheralized nuclei.

Figure 4. Histopathology of thymus from vehicle- (control) and PCB 126 -treated rats. (C = cortex, M = medulla) H&E stain.

A. Control. The thymic cortex is densely cellular with clear delineation from the medulla.

B. Control. At higher magnification, the T-lymphocytes are closely packed.

C. PCB 126. The thymic cortex is thinner than that in controls with scattered vacuoles.

D. PCB 126. At higher magnification, the cortex consists of a mixed population of T-lymphocytes and macrophages surrounded by a clear space (vacuoles from C).

The increase in liver mass in PCB 126 treated rats was accompanied by an increase in the hepatic microsomal cytochrome P-450 activities CYP 1A1 (ethoxyresorufin O-deethylase, EROD) and CYP 1A2 (methoxyresorufin O-demethylase, MROD). EROD and MROD activities were significantly increased 43-fold and 10-fold, respectively, in PCB 126 – treated rats (Table 4). In contrast, a decrease (60%) in hepatic cytosolic SeGPx activity was observed in PCB 126-exposed livers (Table 4), which mirrors the decrease in hepatic selenium levels (Figure 2). Total GPx activity was only decreased 25% by PCB 126 (Table 4). These results indicate a differential regulation of the cytochrome P450 and antioxidant enzyme activities studied.

Table 4.

Effect of PCB126 on CYP1A, SeGPx, and Total GPx Activities

| Corn Oil | PCB 126 | |

|---|---|---|

| Total GPx (nmol/min/mg protein) | 682 ± 71 | 510 ± 28** |

| SeGPx (nmol/min/mg protein) | 480 ± 32 | 196 ± 17* |

| EROD Activity (nmol/min/mg protein) | 0.039 ± 0.007 | 1.67 ± 0.15** |

| MROD Activity (nmol/min/mg protein) | 0.017 ± 0.003 | 0.161 ± 0.013** |

Data are mean ± SEM (n=4)

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

4. Discussion

The toxicity of a specific PCB congener depends upon its chlorination pattern which determines its potential for metabolic activation or detoxification and binding avidity to various cellular receptors. The most studied PCB congeners are the co-planar, non-ortho substituted PCBs, known as dioxin-like PCBs, because of their structural resemblance to TCDD and their ability to bind to the AhR and induce CYP1A enzymes (Bandiera et al. 1982; Hestermann et al. 2000). PCB 126 is known as the most toxic of these dioxin-like PCB congeners. Thus, the goal of this study was to elucidate the congener-specific potency of this dioxin-like PCB to induce oxidative stress related effects on the hepatic redox status and on hepatic metals homeostasis, antioxidant enzymes and cellular/tissue morphology.

PCB 126-treatment produced a significant decrease in total liver glutathione levels. However, this was not accompanied by an increase in GSSG, the oxidized form of glutathione, suggesting that either the reduction of total GSH is due to covalent binding, for example to a PCB metabolite, or the GSSG was very efficiently reduced back to GSH or excreted into the bile. Treatment of rats with up to 600 μmol/kg PCB 77 over a 3 week period did not cause a decrease in total glutathione (Twaroski et al. 2001b). This provides further evidence of the potency of PCB 126 to cause liver toxicity, compared to PCB 77. In the above mentioned experiment a significant increase in glutathione reductase was observed (Twaroski et al. 2001b). The higher hepatic glutathione reductase activity may suggest that the reduction of hepatic glutathione, in the presence of sufficient reducing equivalents, was not rate limiting.

To our knowledge this is the first report about increased copper levels in the liver of rats after PCB-exposure. This increase in the prooxidant copper after exposure to PCB 126, which has also been seen in TCDD-treated rats (Elsenhans et al. 1991; Wahba et al. 1988), may result in an increased production of ROS. Nishimura and coworkers reported increased Cu-levels in the livers of rats after a single dose of 1 μg/kg TCDD, increased 8-oxo-dG levels after 2 μg/kg, and reduced glutathione levels after 4 μg/kg (Nishimura et al. 2001). It was suggested that this increase in hepatic Cu seen in TCDD-treated rats may reflect impaired biliary excretion of Cu, the normal mechanism of maintaining Cu homeostasis (Elsenhans et al. 1991; Mahoney et al. 1955).

Similarly, we did not find reports of an effect of PCBs on zinc levels in the liver, however, studies with TCDD reported unchanged (Wahba et al. 1988) or increased hepatic zinc levels (Nishimura et al. 2001), indicating a possible difference in the modes of action between TCDD and PCB 126. The mechanism resulting in the zinc decrease after PCB 126-treatment is not clear, but oxidative stress seems to be a consequence or causative agent. Zinc’s diminished availability may influence antioxidant enzymes, such as Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase, which could further increase oxidative stress in the liver.

The significant decreases in hepatic levels of selenium, a metal which is considered protective and a component of important antioxidant enzymes, e.g. SeGPx and thioredoxin reducase, certainly signifies an alteration in the redox balance of the cells. Reduction in hepatic Se levels was also reported previously after treatment with PCB 77 (Stemm et al. 2008) and TCDD (Hassan et al. 1985). The mechanism by which hepatic selenium is lost following exposure to AhR agonists is currently unknown and under investigation. As noted by Hassan et al. (1985), selenium is thought to be necessary to partially protect from the toxic effects of TCDD, as rats exposed to TCDD that were deficient in selenium had higher levels of hepatic lipid peroxidation. Also, exposure to 30 μmol/kg PCB 77 caused a similar increase in CYP 1A activity as PCB 126 in our study and resulted in a significant increase in lipid peroxidation in the liver, indicating an inability to cope with increased oxidative events associated with PCB exposure (Fadhel et al. 2002). Notably in the current study, the PCB 126-induced alterations in hepatic levels of zinc, copper and selenium occurred at a dose that did not alter the feed intake or growth of the rats.

Our data confirm the strong effect of dioxin-like compounds on the liver: two weeks after a single injection of 1 μmol/kg PCB 126, an enlarged liver, most likely due to hypertrophic hepatocytes, and the formation of small lipid droplets were observed. This increased liver weight and histologic evidence of hepatocellular degeneration and lipid accumulation point to significant changes taking place in the liver during PCB 126 exposure. Hepatocellular vacuolization has also been described in immature ovariectomized female C57BL/6 mice treated with PCB 126 (Kopec et al. 2008). In the latter study, complementary microarray and clinical chemistry data suggested the lipid accumulation resulted from the disruption of hepatic lipid uptake and metabolism. The observed thymic change in consistent with early atrophy which is a well known response to PCB exposure; the immune system is among the most sensitive of all organ systems to PCBs.

Apart from lipid deposition, our biochemical and histological data support the proliferation of the endoplasmic reticulum and the induction of cytochrome P-450 as a basis of the liver hypertrophy observed in the PCB 126-treated rats. Over 40-fold increase in CYP1A1 (EROD) and ~10-fold increase in CYP1A2 (MROD) were measured in the current study after PCB 126-treatment. Compared to this a twice-weekly i.p. injection of 100 μmol/kg of the dioxin-like congener PCB 77 resulted in a similar increase in liver weight, but increased EROD activity ~35-fold after the first week and ~18-fold after the second week (Twaroski et al. 2001a). The WHO suggested TEF of PCB 126 and PCB 77 are 0.1 and 0.0001, respectively (Van den Berg et al. 1998). By comparison, 3 nmol/kg TCDD was able to produce a 36-fold and 11-fold induction in EROD and MROD activities, respectively (Santostefano et al. 1999). Transcriptional activation of the AhR gene battery includes the induction of a broad range of phase I and phase II enzymes. These changes in gene transcription may disrupt antioxidant homeostasis (Dostalek et al. 2008; Pereg et al. 2006). Notably CYP 1A, a key enzyme in the biotransformation of xenobiotics, may cause toxicity by producing toxic xenobiotic metabolites (McLean et al. 2000; Pereg et al. 2002), or may increase ROS production through the uncoupling of the cytochrome P450 catalytic cycle (Lewis and Pratt 1998; Schlezinger et al. 1999).

PCB mixtures and the dioxin-like PCB 77 have also been shown to decrease the activity of the antioxidant selenoenzyme, SeGPx (Schramm et al. 1985), and decrease the mRNA for the enzyme and total selenium within the liver (Twaroski et al. 2001b). Our results show that PCB 126’s effect on SeGPx was very pronounced; the level of the enzyme down by about 60% after only 1 μmol/kg PCB 126. This reduction in hepatic SeGPx activity may increase oxidative stress by reducing the liver’s capacity to remove hydrogen peroxide. In a separate study we found that PCB 126 also suppresses hepatic catalase activity, further diminishing the liver’s ability to remove hydrogen peroxide (Robertson et al. 2007). The PCB 126-induced decrease in total GPx activity, which consists of both SeGPx and glutathione transferase (GST) activities, was diminished, but at a lower magnitude to that of SeGPx, suggesting an induction of GST (Prohaska 1980; Schramm et al. 1985). In contrast, much higher doses of PCB 77 reduced Se-GPx activity only by ~20 to 30% (Twaroski et al. 2001b), showing the potent toxicity of PCB 126. Similar findings of GPx activity decrease have also been observed in rats treated with TCDD with a dose as low as 3 nmol/kg (Stohs et al. 1986). The loss of SeGPx activity can be linked to the loss of hepatic selenium and GSH (Chen et al. 1990), as exposure to PCB 126 significantly diminished both of these key components of the enzyme reaction.

Studies employing various routes of administration are difficult to compare. Even if we assume that 100% of the oral dose is absorbed, it is clear that the current study was conducted well above the stated NOAEL of 0.01 μg/kg body weight/day of PCB 126 (Chu et al. 1994), and above the stated LOAEL of 0.74 μg/kg body weight/day (ATSDR 2000). This indicates a broad range of doses, insufficient to cause impairment in growth rates, but sufficient to significantly alter the redox status of the liver, a state reflected by alterations in antioxidant enzymes, reductions in GSH, and the metals, selenium and zinc, with concomitant increases in copper. These findings may well prove to be useful in future studies of biomarkers of PCB exposure/effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their laboratory colleagues for their assistance with the animal studies and for useful discussions. This study was supported by the Iowa Superfund Basic Research Program (P42 ES013661) from NIEHS. Gregor Luthe received support from Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Bonn, Germany. Contents reflect the views of the authors and do not represent any official view(s) of NIEHS or NIH. Funds were also available from the Environmental Health Sciences Research Center (P30 ES05605).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson ME. Determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide in biological samples. Methods Enzymol. 1985;113:548–555. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(85)13073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MJ, Higgins PG, Davis LR, Willman JS, Jones SE, Kidd IM, Pattison JR, Tyrrell DA. Experimental parvoviral infection in humans. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:257–265. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATSDR. Toxicological Profile for Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs). 2000

- Bandiera S, Safe S, Okey AB. Binding of polychlorinated biphenyls classified as either phenobarbitone-, 3-methylcholanthrene- or mixed-type inducers to cytosolic Ah receptor. Chem Biol Interact. 1982;39:259–277. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(82)90045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke MD, Mayer RT. Ethoxyresorufin: direct fluorimetric assay of a microsomal O-dealkylation which is preferentially inducible by 3-methylcholanthrene. Drug Metab Dispos. 1974;2:583–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LC, Borges T, Glauert HP, Knight SA, Sunde RA, Schramm H, Oesch F, Chow CK, Robertson LW. Modulation of selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase by perfluorodecanoic acid in rats: effect of dietary selenium. J Nutr. 1990;120:298–304. doi: 10.1093/jn/120.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu I, Villeneuve DC, Yagminas A, LeCavalier P, Poon R, Feeley M, Kennedy SW, Seegal RF, Hakansson H, Ahlborg UG, et al. Subchronic toxicity of 3,3′,4,4′,5-pentachlorobiphenyl in the rat. I. Clinical, biochemical, hematological, and histopathological changes. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1994;22:457–468. doi: 10.1006/faat.1994.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condell RA, Tappel AL. Evidence for suitability of glutathione peroxidase as a protective enzyme: studies of oxidative damage, renaturation, and proteolysis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;223:407–416. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90604-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dostalek M, Hardy KD, Milne GL, Morrow JD, Chen C, Gonzalez FJ, Gu J, Ding X, Johnson DA, Johnson JA, Martin MV, Guengerich FP. Development of oxidative stress by cytochrome P450 induction in rodents is selective for barbiturates and related to loss of pyridine nucleotide-dependent protective systems. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17147–17157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802447200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsenhans B, Forth W, Richter E. Increased copper concentrations in rat tissues after acute intoxication with 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Arch Toxicol. 1991;65:429–432. doi: 10.1007/BF02284268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle J, Hearn R. Development of an accurate procedure for the determination of arsenic in fish tissues of marine origin by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometrystar. Spectrochimica Acta Part B: Atomic Spectroscopy. 2006;61:438–443. [Google Scholar]

- Fadhel Z, Lu Z, Robertson LW, Glauert HP. Effect of 3,3′,4,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl and 2,2′,4,4′,5,5′-hexachlorobiphenyl on the induction of hepatic lipid peroxidation and cytochrome P-450 associated enzyme activities in rats. Toxicology. 2002;175:15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JW, Campbell J, Muralidhara S, Bruckner JV, Ferguson D, Mumtaz M, Harmon B, Hedge JM, Crofton KM, Kim H, Almekinder TL. Effect of PCB 126 on hepatic metabolism of thyroxine and perturbations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis in the rat. Toxicol Sci. 2006;90:87–95. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith OW. Determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide using glutathione reductase and 2-vinylpyridine. Anal Biochem. 1980;106:207–212. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen LG. Food chain modification of the composition and toxicity of PCB residues. Rev Environ Toxicol. 1987;3:149–212. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan MQ, Stohs SJ, Murray WJ, Birt DF. Dietary selenium, glutathione peroxidase activity, and toxicity of 2,3,7,8-tetrachloro-dibenzo-p-dioxin. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1985;15:405–415. doi: 10.1080/15287398509530668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hestermann EV, Stegeman JJ, Hahn ME. Relative contributions of affinity and intrinsic efficacy to aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand potency. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000;168:160–172. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori M, Kondo H, Ariyoshi N, Yamada H, Hiratsuka A, et al. Changes in the hepatic glutathione peroxidase redox system produced by coplanar polychlorinated biphenyls in Ah-responsive and -less responsive strains of mice: mechanism and implications for toxicity. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 1997;3:267–275. doi: 10.1016/s1382-6689(97)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopec AK, Boverhof DR, Burgoon LD, Ibrahim-Aibo D, Harkema JR, Tashiro C, Chittim B, Zacharewski TR. Comparative toxicogenomic examination of the hepatic effects of PCB126 and TCDD in immature, ovariectomized C57BL/6 mice. Toxicol Sci. 2008;102:61–75. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence RA, Burk RF. Glutathione peroxidase activity in selenium-deficient rat liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1976;71:952–958. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)90747-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DF, Pratt JM. The P450 catalytic cycle and oxygenation mechanism. Drug Metab Rev. 1998;30:739–786. doi: 10.3109/03602539808996329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig G, Esch H, Robertson LW. Polyhalogenierte Bi- und Terphenyle. In: Dunkelberg H Gebel T, Hartwig A., editors. Handbuch der Lebensmitteltoxikologie. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Luthe GM, Schut BG, Aaseng JE. Monofluorinated analogues of polychlorinated biphenyls (F-PCBs): Synthesis using the Suzuki-coupling, characterization, specific properties and intended use. Chemosphere. 2009;77:1242–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney JP, Bush JA, Gubler CJ, Moretz WH, Cartwright GE, Wintrobe MM. Studies on copper metabolism. XV. The excretion of copper by animals. J Lab Clin Med. 1955;46:702–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCray PB, Gibson DD, Fong KL, Hornbrook KR. Effect of glutathione peroxidase activity on lipid peroxidation in biological membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;431:459–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean MR, Twaroski TP, Robertson LW. Redox cycling of 2-(x′-mono, -di, -trichlorophenyl)- 1, 4-benzoquinones, oxidation products of polychlorinated biphenyls. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;376:449–455. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister A, Anderson ME. Glutathione. Annu Rev Biochem. 1983;52:711–760. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.52.070183.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller AS, Pallauf J. Down-regulation of GPx1 mRNA and the loss of GPx1 activity causes cellular damage in the liver of selenium-deficient rabbits. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2002;86:273–287. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0396.2002.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura N, Miyabara Y, Suzuki JS, Sato M, Aoki Y, Satoh M, Yonemoto J, Tohyama C. Induction of metallothionein in the livers of female Sprague-Dawley rats treated with 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Life Sci. 2001;69:1291–1303. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson A, Safe SH, Robertson LW, Thomas PE, Ryan DE, Reik LM, Levin W. Immunochemical quantitation of cytochrome P-450 isozymes and epoxide hydrolase in liver microsomes from polychlorinated or polybrominated biphenyl-treated rats. A study of structure-activity relationships. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:5967–5976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereg D, Robertson LW, Gupta RC. DNA adduction by polychlorinated biphenyls: adducts derived from hepatic microsomal activation and from synthetic metabolites. Chem Biol Interact. 2002;139:129–144. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(01)00292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereg Y, Lam S, Teunisse A, Biton S, Meulmeester E, Mittelman L, Buscemi G, Okamoto K, Taya Y, Shiloh Y, Jochemsen AG. Differential roles of ATM- and Chk2-mediated phosphorylations of Hdmx in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6819–6831. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00562-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohjanvirta R, Sankari S, Kulju T, Naukkarinen A, Ylinen M, Tuomisto J. Studies on the role of lipid peroxidation in the acute toxicity of TCDD in rats. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1990;66:399–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1990.tb00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prohaska JR. The glutathione peroxidase activity of glutathione S-transferases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;611:87–98. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(80)90045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson LW, Berberian I, Borges T, Chen L-C, Chow C, Glauert HP, Filser JG, Thomas H. Suppression of peroxisomal enzyme activities and cytochrome P450 4A isozyme expression by congeneric polybrominated and polychlorinated biphenyls. PPAR Research. 2007;2007:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2007/15481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safe SH. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs): environmental impact, biochemical and toxic responses, and implications for risk assessment. Critical reviews in toxicology. 1994;24:87–149. doi: 10.3109/10408449409049308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santostefano MJ, Richardson VM, Walker NJ, Blanton J, Lindros KO, Lucier GW, Alcasey SK, Birnbaum LS. Dose-dependent localization of TCDD in isolated centrilobular and periportal hepatocytes. Toxicol Sci. 1999;52:9–19. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/52.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlezinger JJ, White RD, Stegeman JJ. Oxidative inactivation of cytochrome P-450 1A (CYP1A) stimulated by 3,3′,4,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl: production of reactive oxygen by vertebrate CYP1As. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:588–597. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.3.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm H, Robertson LW, Oesch F. Differential regulation of hepatic glutathione transferase and glutathione peroxidase activities in the rat. Biochem Pharmacol. 1985;34:3735–3739. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(85)90239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemm DN, Tharappel JC, Lehmler HJ, Srinivasan C, Morris JS, Spate VL, Robertson LW, Spear BT, Glauert HP. Effect of dietary selenium on the promotion of hepatocarcinogenesis by 3,3′, 4,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl and 2,2′, 4,4′, 5,5′-hexachlorobiphenyl. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233:366–376. doi: 10.3181/0708-RM-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stohs SJ, Al-Bayati ZF, Hassan MQ, Murray WJ, Mohammadpour HA. Glutathione peroxidase and reactive oxygen species in TCDD-induced lipid peroxidation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1986;197:357–365. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5134-4_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twaroski TP, O’Brien ML, Larmonier N, Glauert HP, Robertson LW. Polychlorinated biphenyl-induced effects on metabolic enzymes, AP-1 binding, vitamin E, and oxidative stress in the rat liver. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2001a;171:85–93. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twaroski TP, O’Brien ML, Robertson LW. Effects of selected polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) congeners on hepatic glutathione, glutathione-related enzymes, and selenium status: implications for oxidative stress. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001b;62:273–281. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00668-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg M, Birnbaum L, Bosveld AT, Brunstrom B, Cook P, Feeley M, Giesy JP, Hanberg A, Hasegawa R, Kennedy SW, Kubiak T, Larsen JC, van Leeuwen FX, Liem AK, Nolt C, Peterson RE, Poellinger L, Safe S, Schrenk D, Tillitt D, Tysklind M, Younes M, Waern F, Zacharewski T. Toxic equivalency factors (TEFs) for PCBs, PCDDs, PCDFs for humans and wildlife. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106:775–792. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahba ZZ, al-Bayati ZA, Stohs SJ. Effect of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin on the hepatic distribution of iron, copper, zinc, and magnesium in rats. J Biochem Toxicol. 1988;3:121–129. doi: 10.1002/jbt.2570030206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizawa K, Heatherly A, Malarkey DE, Walker NJ, Nyska A. A critical comparison of murine pathology and epidemiological data of TCDD, PCB126, and PeCDF. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:865–879. doi: 10.1080/01926230701618516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]