Abstract

With improvements to DNA sequencing technologies, including the advent of massively parallel sequencing to perform “deep sequencing” of tissue samples, the ability to determine all of the nucleotide variations in a tumor becomes a possibility. This information will allow us to more fully understand the heterogeneity within each tumor, as well as to identify novel genes involved in cancer development. However, the new challenge that arises will be to interpret the pathogenic significance of each genetic variant. The enormity and complexity of this challenge can be demonstrated by focusing on just the genes involved in the hereditary colon cancer syndromes, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and hereditary non-polyposis coli (HNPCC). The genes responsible for each disease were identified almost two decades ago -- APC for FAP and the MMR genes for HNPCC - and a large number of germline variations have been identified in these genes in hereditary cancer patients. However, relating the effect of an individual genotype to phenotype is not always straightforward. This review focuses on the roles of the APC and MMR genes in tumor development and the work that has been done to relate different variants in each gene to functional aberrations and ultimately tumorigenesis. By considering the work that has already been done on two well-defined diseases with clear genetic associations, one can begin to understand the challenges that lie ahead as new genes and gene mutations are discovered through tumor sequencing.

1. Introduction

A more individualized approach to cancer treatment and prevention will depend upon our ability to identify and understand the molecular changes that drive the tumorigenic process in each individual tumor. As cancer is a highly complex, heterogeneous disease, this seems like a daunting task. We may be entering an era, however, where the molecular changes that underlie a given cancer can be described thoroughly, allowing clinicians and scientists to assess how complex the problem is. The advancement of DNA sequencing technologies spurred by the human genome sequencing project is allowing researchers to determine how many somatic mutations exist in a tumor [1-5]. The number of mutations may be as high as 80 or more [1,2] or it may be as small as eight to ten [3]. The differences likely are due to the tumor type, the methods involved for detecting alterations and the threshold for predicting whether an alteration is significant to phenotype. Determining which variations drive tumor phenotype will depend upon an ability to ascertain the cellular function affected by each somatic change.

This quest to relate genotype to phenotype remains the great challenge of basic cancer research and the key to developing effective targeted therapies. Nothing, perhaps, demonstrates this challenge better than contemplating how much, yet how little, we understand about the relationship between genotype and phenotype in hereditary colorectal cancer (CRC). Because of the abundance of cases in the population, the ability to identify and isolate benign precursor lesions in the colon, and the identification of hereditary diseases with increased predisposition to CRC development, colon cancer has been one the most studied cancers and serves as a model for understanding basic principles of tumorigenesis that may apply to all tumor types [6]. Hereditary CRC, that is, those cases in patients with a family history of colon cancer where a clear genetic basis for the disease has been defined, accounts for 4-6% of colon cancer incidence [7]. The two major syndromes that account for the vast majority of hereditary cases include: i) Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) caused by inherited mutations in the APC gene, and ii) Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colon Cancer (HNPCC) caused by inherited mutations in the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes. Though the genes responsible for these diseases have been identified, researchers are still attempting to fully understand how mutations in these specific genes cause cancer. Both APC and the DNA MMR genes function genetically as tumor suppressors, yet it is not always clear how the alteration identified in these genes affect gene function. This review will focus on these two diseases, FAP and HNPCC, the function of the APC and DNA MMR genes involved in each disease and subsets of variants of these genes that have been studied to determine their effect on tumorigenesis.

2. Familial Adenomatous Polyposis

FAP is an autosomal, dominant disorder characterized by the presence of hundreds to thousands of benign, adenomatous polyps that carpet the colon and rectum of patients. This polyposis phenotype usually initiates during the second or third decade of life. Ninety percent of these polyps will remain less than 0.5 cm in diameter. However, if the colon is not removed there is nearly a 100% chance that one of these lesions will progress to an adenocarcinoma [8]. Extracolonic manifestations of the disease also occur and include small bowel, gastric and periampullary tumors, adrenal adenomas and carcinomas, and thyroid carcinomas. Other associated lesions include desmoid tumors and congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE) [9]. The association of polyposis with certain extracolonic symptoms is often designated as Gardner syndrome, marked by the appearance of multiple osteomas, multiple epidermoid cysts, soft fibromas of the skin, mesenteric fibromatosis, desmoid tumors or dental abnormalities [8]. Extremely rare cases of FAP combined with central nervous system cancers, particularly meduloblastomas, are referred to as Turcot’s syndrome [9].

Cytogenetic analyses of adenomas and carcinomas from FAP patients revealed frequent loss of heterozygosity (LOH) on chromosome arms 5q, 8p, 17p and 18q [10]. These regions were assumed to contain tumor suppressor genes, whose mutation would contribute to a loss of growth control. A breakthrough in the discovery of the gene responsible for FAP came when an interstitial deletion on the long arm of chromosome 5 was identified in a patient with Gardner syndrome [11]. The region around the deletion was further probed in genomic DNA from other FAP families in order to more precisely map the locus [12-14] leading to the identification of three candidate genes within small nested deletions from two unrelated FAP patients [15]. One of these candidates was found to be mutated in four of the patients studied and was termed APC for adenomatous polyposis coli [16].

The APC gene is composed of 15 exons encoding a 2,844 amino acid peptide with exon 15 being the largest coding region (6.5kb) [16]. Mutational and functional studies indicate that APC functions as a tumor suppressor gene and that FAP is an autosomal dominant disease in which the patient inherits one mutant allele followed by a somatic mutation in the remaining wild-type allele. Analysis of sporadic colorectal adenomas and carcinomas revealed that APC mutation occurred in nearly 70-80% of all colorectal tumors and is believed to be an early event in the tumorigenesis process [17,18], though this point has been debated [19].

3. The Role of the APC Gene in Tumorigenesis

3.1 APC Regulation of the WNT Signaling Pathway

Restoration of a normal copy of the APC gene into colorectal cancer cells results in clones with reduced doubling times, reduced growth in soft agar and inhibited ability to generate tumors upon injection into athymic mice, confirming the hypothesis that APC functions as a tumor suppressor [20-22]. A major clue as to the mechanism by which APC functions to protect against tumorigenesis came from the discovery that the APC protein interacts with β-catenin [23,24]. At the time, β-catenin was known to interact with E-cadherin and be an important molecule for the formation of adherens junctions in epithelial cells, thus it was thought that APC may play a role in the regulation of cell adhesion. However, studies of β-catenin homologs in flies and frogs revealed that β-catenin played a role in signal transduction and that overexpression results in the duplication of the dorsal embryonic axis [25,26] - a phenotype similar to that observed when Wnt ligand molecules were overexpressed [27]. β-catenin was eventually demonstrated to interact with members of the TCF/LEF family of transcription factors to activate transcription of many gene targets including C-MYC, Cyclin D1, CD44 and BMP4 [28-32]. The discovery that reintroduction of APC into colorectal cancer cells substantially reduces β-catenin levels [33], and β-catenin-activated transcription [34], led to a model in which APC regulates cell growth through its ability to regulate β-catenin levels.

APC regulation of β-catenin-induced gene activation appears to function through multiple mechanisms. Initially, it was observed that an interaction between β-catenin and APC in a complex with the serine/threonine kinase GSK3β and the scaffold protein axin promotes phosphorylation and ubiquitin-mediated degradation of β-catenin [35]. APC has also been shown to enter into the nucleus and promote the export of β-catenin, reducing its ability to activate transcription [36]. Additionally, APC interacts with the C-terminal binding protein (CtBP) in a complex with the β-TrCP protein at enhancers of Wnt target genes in competition with β-catenin-activating complexes to directly repress these genes [37].

3.2 APC and Cell Migration

While the role of APC in regulating the Wnt signaling pathway clearly has implications for tumor formation, loss of wild-type APC may affect tumorigenesis through other mechanisms as well. APC has been hypothesized to play a role in regulating cell migration. Overexpression of APC in the small intestine leads to misregulated migration of epithelial cells [38], whereas the loss of APC expression abrogates cell migration along the crypt-villus axis [39]. APC is observed at the ends of microtubules at the leading edge of the plasma membrane in actively migrating epithelial cells in culture [40]. siRNA knock-down of APC in cells decreases microtubule stability affecting cell migration [41]. This APC-dependent stabilization of microtubules is believed to be mediated through an interaction of the C-terminus of APC with the microtubule binding protein EB1 [42,43].

APC may also regulate cell migration through different pathways. APC has been shown to interact with actin cytoskeleton proteins including the guanine exchange factors (GEF) Asef1 and Asef2 [44-46]. APC interaction with both Asef1 and Asef2 stimulates their GEF activity, leading to the activation of Cdc42. Activated Cdc42 is involved in re-organizing the actin cytoskeletal network, producing lamellipodia and filopodia, and enhancing cell migration [44-46]. It was observed that C-terminally truncated APC mutants retain the ability to bind to both Asef1 and Asef2 and stimulate these proteins even more than wild-type APC [45,47]. Another actin-filament regulating protein that interacts with APC is the scaffold protein IQGAP1 [48]. IQGAP1 is an effector molecule of Cdc42 and Rac1. IQGAP1 is thought to recruit APC to the leading edge of migrating cells resulting in proper actin network formation and simultaneous microtubule destabilization to allow for cell migration [48].

3.3 A Role for APC in Maintaining Chromosome Stability

Loss of APC function has also been suggested to lead to chromosomal instability (CIN). CIN, a mechanism by which the chromosomal content of a cell changes, is believed to be a driving force in tumorigenesis, resulting in changes to gene expression patterns as well as increased frequencies of LOH [49]. Loss of APC was first suspected to play a role in CIN when it was observed that mouse embryonic stem cells homozygous for the Min allele (a mutated version of Apc that results in a truncated protein product) displayed extensive chromosome aberrations [50]. Furthermore, whereas wild-type cells displayed mitotic spindles with microtubules that connected metaphase chromosomes with the centrosome in an ordered fashion, the spindles from ApcMin/Min cells showed multiple, randomly projected microtubules [50]. Reduction of APC by siRNA in U2OS and HCT116 cells leads to reduced association of the mitotic checkpoint proteins Bub1 and BubR1 with the kinetochores, suggesting that APC may play a role in regulating the mitotic spindle checkpoint [51]. However, a similar study performed in HeLa cells showed no effect of loss of APC on checkpoint protein levels or on chromosomal alignment during metaphase [52]. These authors do observe increased misorientation of paired sister chromatids upon APC knockdown, suggesting that loss of APC contributes to CIN by promoting low-level chromosome segregation errors that are not detectable by the checkpoint apparatus.

4. APC Mutations in FAP

4.1 Truncation Mutations and the First Hit-Second Hit Association

Analyzing the spectrum of APC gene mutations in FAP patients may provide insight into the functions of the APC protein affected during tumorigenesis. Over 95% of the germline mutations identified in the APC gene are frameshift or nonsense mutations that result in a truncated protein product [53]. The majority of germline mutations in APC occur in the 5′ half of the gene leading to the elimination of most, if not all, of the 20-amino acid repeats involved in regulating β-catenin levels and SAMP repeats involved in axin binding (Figure 1) [53-55]. However, these truncated proteins also lack the microtubule and EB1 binding domains located in the C-terminal end of the protein. A careful analysis of the location of the APC germline mutation compared to the polyposis phenotype reveals that patients with mutations near codon 1300, between the first and second 20-amino acid repeats, develop particularly severe disease characterized by > 2000 polyps and earlier-onset cancer formation [56,57].

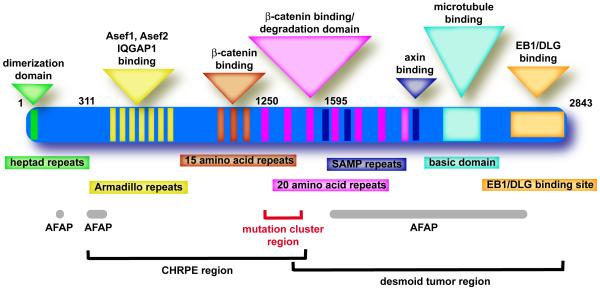

Fig. 1.

The functional domains of the APC protein. Shown are the identified amino acid domains of the APC protein (rectangles) and the implicated functions of each domain (triangles). Also highlighted are particular disease phenotypes that appear to associate with mutations that truncate the APC protein in certain regions along with key codon positions along the protein.

The location of the original germline mutation in APC may also influence the position and type of mutation in the remaining wild-type allele during tumorigenesis [58-60]. Patients with a germline mutation near codon 1300 tend to suffer loss of heterozygosity (LOH) mutations as the second ‘hit’. These LOH events did not result in a change in APC gene dosage, though, suggesting a gene duplication event occurred resulting in two similarly mutated APC alleles [60]. In tumors from patients with germline mutations elsewhere in the APC gene, the second ‘hit’ was more commonly a protein truncating mutation; most within a specific region between codons 1250 and 1450 referred to as the mutation cluster region (Figure 1). The location of the protein truncating mutation affects the number of 20-amino acid repeats remaining. Mutations near codon 1300 would result in an APC protein with one 20-amino acid repeat. The ability of APC to regulate β-catenin activity appears to depend upon the number of 20-amino acid repeats present in the protein [61]. Even truncated APC with one 20-amino acid repeat is capable of exporting β-catenin out of the nucleus, suggesting APC proteins truncated near codon 1300 still maintain some β-catenin downregulating activity [62]. Following LOH and gene duplication, the cell would be left only with an APC protein containing one repeat. However, truncating mutations upstream of codon 1264 would result in a protein with no 20-amino acid repeats remaining, perhaps creating a selective pressure for the second ‘hit’ in these tumors to occur in the MCR resulting in some APC protein with one or two 20-amino acid repeats. Thus, some ability to regulate β-catenin activity appears desirable in the tumor [59,60].

4.2 Attenuated FAP

A less severe form of FAP, marked by the presence of <100 polyps and a later onset of CRC, is referred to as attenuated FAP (AFAP) and accounts for about 10% of FAP cases. The APC germline mutations in AFAP patients tend to cluster in three regions of the gene: i) the 5′ end, particularly in the regions spanning exons 3 and 4, ii) within exon 9, most frequently within a region of exon 9 that is alternatively spliced, and iii) the very 3′ end of the gene beyond codon 1595 (Figure 1) [57,63-65]. It is not immediately obvious why mutations in these regions of the gene would lead to a milder form of the disease. Mutations in the 5′ end of the gene in exons 3 and 4 have been identified most frequently in AFAP patients and it has been speculated that they may result in short APC protein products that are incapable of forming dimers with wild-type APC [66]. APC has also been reported to be alternatively spliced in this region which would result in a reduction in the levels of mutant protein [67]. Some AFAP alleles may still produce functional APC protein through use of an internal ribosomal entry site, leading to internal initiation of translation downstream of the mutation site [68]. The effect of mutations in alternatively spliced regions either in exon 9 or in the 5′ end of the gene may not be due to the production of a mutant protein, particularly considering that the alternatively spliced transcripts would produce an APC protein with mostly normal sequence. However, the amounts of wild-type APC protein may be reduced which may mildly affect β-catenin regulation or other APC functions. This has led some to speculate that a third ‘hit’ in APC may be necessary in patients carrying these AFAP germline mutations [69]. The effect of 3′ mutations is not entirely clear. While these mutations could potentially affect the microtubule and EB1 binding domains without disrupting β-catenin function, it has also been suggested that these mutations may function as null alleles as some of these mutations do not appear to produce a truncated protein product [70].

The association between the site of the APC truncating mutation and the severity of disease may have clinical implications. The severity of the disease in a given patient may direct genetic testing to focus on particular regions of the rather large APC gene. In addition to disease severity, some of the extracolonic phenotypes reported in FAP patients may be associated with mutations in certain regions of the APC gene [57]. The presence of CHRPE appears restricted to patients with inherited mutations between codons 311 and 1465. Desmoid tumors generally occur in FAP patients with mutations downstream of codon 1400 (Figure 1). The relationship between genotype and phenotype may affect decisions regarding clinical management of FAP patients. At risk family members carrying germline mutations near codon 1300 are recommended to begin colonoscopy surveillance early in childhood due to increased propensity for early-onset disease associated with those mutations [71]. However, there exist enough contradictions in the literature to caution against the sole use of genotype in making clinical decisions [57,69]. In the case of AFAP, though the reduced severity and relatively later age of onset in AFAP patients might suggest that those with germline mutations in the AFAP regions of APC (Figure 1) could delay surveillance or avoid prophylactic colectomy, most researchers still caution against such decisions [69]. The studies of AFAP families are still too limited and are marked by contradictions. For example, multiple studies note both intra- and interfamily variation in AFAP phenotype in patients carrying the same mutation [64,69,72,73]. There may be a selection bias in many of these studies as the family is often brought to researchers’ attention because the proband displays more classical polyposis (> 100 polyps).

Complicating matters further, within the last decade, families with an AFAP-like phenotype have been described that do not appear to carry any germline mutation in APC. Instead, it was noted that the APC gene in the tumor sample displayed a high proportion of somatic G:C→T:A mutations. This mutation spectrum was highly similar to that observed in a mutY strain of bacteria. MutY is an adenine glycosylase that removes a mispaired adenine from 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine-adenine (OG-A) mismatches [74]. Indeed, it was determined that the patients carried germline biallelic mutations in the human MUTYH gene, making it the first base-excision repair gene involved in hereditary cancer [75]. Over 25% of AFAP-like patients without a germline APC mutation have been shown to carry bi-allelic mutations in MUTYH. For further discussion of MUTYH and associated variants, the reader is referred to other reviews on this topic [76,77].

4.3 Missense mutations in APC

Nonsense and frameshift mutations that lead to premature stop codons result in a truncated APC protein product that eliminates key functional domains. However, a small number of missense variants of APC have been identified in the germline of patients with multiple polyps and CRC that may contribute to disease. The immediate effect of these single amino acid changes on function of the APC protein is harder to predict. Two missense variants most frequently reported are I1307K and E1317Q [78-82]. The I1307K variant has been identified almost exclusively in patients of Ashkenazi Jewish descent and has been associated with increased risk of multiple adenomas and CRC similar to an AFAP phenotype. Though the altered residue lies in a functionally important domain between 20-amino acid repeats 1 and 2, no functional consequence for altering this isoleucine to a leucine has been described yet. However, the nucleotide change that results in the I1307K allele is a T→A transversion at position 3920 which converts an A3TA4 sequence to an A8 tract. This mononucleotide repeat appears susceptible to polymerase slippage and mispairing during DNA replication resulting in increased frameshift mutations in this newly created tract. In one study of 127 colorectal tumors from patients carrying the germline I1307K mutation, 42% of the tumors harbored additional frameshift mutations within the A8 tract [83]. The mechanism for the increased frameshift mutations in the repeat region, a phenotype normally associated with defects in DNA MMR, was not described. Even though the I1307K variant has been associated with increased adenomas in certain select populations, other studies have identified no increased risk of CRC in carriers of this germline variant. Possibly the association is not between I1307K and CRC risk, but rather some genetic or environmental factor that increases the risk of frameshift mutations in this newly created A8 tract [84]. The relationship between the E1317Q variant of APC and CRC risk is even less clear. An association between E1317Q and multiple adenomatous polyps has been reported along with a weak association with CRC [79,80,82]. However, more recent studies examining larger numbers of CRC patients and controls observed almost no association between the variant and increased CRC risk [81,82]. In total, greater than 60 different germline missense variants of APC have been described in the literature or APC mutation databases as potentially pathogenic [53,79-81,85-87]. However, the number of patients and controls examined is small for most of the variations reported and larger studies examining particular variants fail to find a significant association between some of these variants and CRC risk [81,82].

In addition to an alteration of the amino acid sequence, missense variants may also affect the final protein product by disrupting splicing of the primary transcript. The variations may disrupt regulatory sequences such as splicing enhancers or silencers that result in the splicing machinery skipping exons in the mutant gene [88]. Silent variants which affect the genomic sequence but are still predicted to encode for the same amino acid may also affect splicing, particularly if they fall near an exon-intron boundary. An examination of the primary transcript from different patients harboring missense or silent variants in APC revealed that the majority of them result in exon skipping due to aberrant splicing [89,90]. Variants that result in the skipping of exons 4, 11, and 14 result in premature stop codons and a truncated protein product suggesting these variants are likely pathogenic. A variant from an AFAP patient that leads to the skipping of exon 13 did not result in loss of proper reading frame. However, it is believed that this variant may be pathogenic because it results in the removal of a complete heptad repeat region from the APC protein [90]. Thus, while often missense and, especially, silent variants are excluded from further consideration during screens for cancer-associated mutations, these variants may very likely have pathogenic consequences.

4.4 Functional Analysis of APC variants

To date, one study has attempted to analyze the functional significance of a germline APC variant [86]. An N1026S variant was identified in a Spanish AFAP family in all the affected family members. It was not found in the remaining 440 CRC cases or 203 controls studied. Codon 1026 lies in the first of three 15-amino acid repeats that have been implicated in β-catenin binding [91]. The N1026S variant was shown to disrupt β-catenin binding to the 15-amino acid repeat region of APC. Re-introduction of a full-length APC N1026S into cancer cells lacking endogenous full-length APC leads to a reduction in β-catenin levels and β-catenin/TCF4 mediated transcription, but not to the same extent as wild-type APC [86]. These results provide evidence that a germline APC missense variant identified in an FAP family can affect the function of the APC protein supporting a role for this variant in pathogenicity.

A lack of assays to examine APC function is a challenge to determining the contribution of disease-associated variants to pathogenesis. The large size of the APC protein makes biochemical analyses of the protein difficult. Thus, many studies utilize fragments of the protein to study particular biochemical functions [92]. Studies of an exogenously added full-length APC transgene have been performed in cell culture systems to examine the role of APC in cell growth, cellular transformation, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, β-catenin regulation and cell adhesion [22,33,34,62,93-95]. Any of these assays could be applicable for testing APC variants, though how many studies need to be performed to examine the myriad of APC functions described? A simple analysis of β-catenin localization in response to the introduction of a variant-containing APC would be a relatively simple first screen; as was reported for the N1026S variant described above [86].

Re-introduction of cDNA based transgenes would not assess defects in message stability and splicing. More importantly, such an assay would not asses the disease phenotypes associated with a particular variant - an extremely important question considering the phenotypic variability discussed above. One potentially effective approach for examining genotype/phenotype relationships for APC variants is the use of transgenic mouse models [96]. The first Apc mutant mouse model described was the Multiple intestinal neoplasia (Min) mouse created by random mutagenesis and characterized by the appearance of multiple tumors in the small intestine [97]. The Min allele was later determined to be a truncating mutation at codon 850 in the mouse homolog of the APC gene [98]. Other mouse models of FAP were developed with truncating mutations at different codons of Apc, all showing a similar adenomatous polyp phenotype in the small intestine. However, the number of polyps varied depending on the location of the mutation [96]. The ApcMin mouse develops on average 30 polyps per animal in the small intestine. However, the ApcΔ716 mouse, which contains a truncating mutation at codon 716, develops around 300 polyps per animal [99]. A third model, the Apc1638N, which contains a truncating mutation at codon 1638, develops approximately 3 polyps per animal and appears to survive longer than the ApcMin mice [100]. The difference in disease severity may be linked to the position of the mutation along the Apc gene. The Min allele generates a truncated protein product that lacks the 20-amino acid repeats involved in β-catenin binding and degradation, whereas the 1638N protein product still retains this region. A fourth mouse model carrying a deletion of exon 14, ApcΔ14, results in an animal with a slightly increased disease severity compared to the ApcMin mouse [101]. Though the polypsosis phenotypes in the small intestine were similar between the two mouse models, the ApcΔ14 mouse appears to develop more severe polyposis in the colon and rectum. One difference in the truncated protein products (at codon 580 for ApcΔ14) is that the ApcΔ14 lacks the armadillo repeats involved in binding to Asef 1 and 2 as well as IQGAP [101]. Another mouse model in which exon 14 was deleted in a tissue specific manner displays an increased length of survival compared to both ApcΔ14 and ApcMin, though the animals developed more adenomas in the distal colon with some progressing to carcinoma [102]. The authors speculate that a reduced small intestinal polyp burden may lead to the increased survival. In general, mouse models of FAP have provided a valuable tool for studying the phenotypic effects of various Apc mutations. However, it is an impractical approach to study multiple variants due to the time and expense involved in such studies. Continued research to understand the relationship between APC function and tumor protection will be necessary in order to generate better screens for disease variants. If developed, however, they would provide tremendous information for the counseling and management of CRC patients and their families who harbor these variants.

5. Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colon Cancer

The first documented case of likely HNPCC dates back to the early 20th century. A pathologist at the University of Michigan named Aldred Warthin published the pedigree of his seamstress who had earlier shared with Warthin her concerns that she would die early from colon cancer or some cancer of the female organs since so many other members of her family had before [103]. This work went largely unnoticed until the 1960’s when another pathologist Henry Lynch, hearing a similar story from another patient, was made aware of Warthin’s early work. Lynch spent the rest of his career gathering information on hereditary cancer families, attempting to convince the medical community that another form of hereditary cancer existed besides the well-known hereditary polyposis syndrome FAP. Because of this, HNPCC is also commonly referred to as Lynch syndrome.

HNPCC is an autosomal dominant disorder, similar to FAP, which accounts for 2-7% of the total CRC burden. With the absence of a distinct polyposis phenotype, a detailed family history becomes necessary in diagnosing HNPCC. In 1991, an international panel of physicians and researchers established a list of criteria to assist in identifying HNPCC families [104]. Termed the Amsterdam Criteria, this list is fairly restrictive resulting in a number of familial cancers that, though not diagnosed as HNPCC, may display many HNPCC-like phenotypical and genetic characteristics (Table 1). Additional panels have expanded upon the original Amsterdam criteria, most notably a 1996 meeting in Bethesda, MD, [105] and a second Bethesda meeting in 2002 [106] (Table 1). The guidelines established from these meetings, mainly based on the penetrance of cancer within the families, the location of the tumors and the age of onset in the various family members, have aided the effort to identify potential HNPCC families. HNPCC tumors tend to display an earlier age of onset (~ 44 years old) than sporadic colon cancers and have a propensity to occur in the proximal colon [103]. In addition to colon cancers, HNPCC patients are at increased risk of developing extracolonic cancers, most frequently cancers of the endometrium as well as cancers of the ovary, small intestine, stomach, pancreas, hepatobiliary tract, brain and uro-epithelial tract.

Table 1.

| Amsterdam Criteriaa |

|---|

|

| Bethesda Criteria (Modified)b |

|---|

|

A striking molecular characteristic in more than 90% of colorectal tumors from HNPCC patients is a specific genomic instability event at small repeated sequences in DNA called microsatellite instability (MSI) [107]. MSI occurs when the DNA polymerase slips during replication of highly repetitive regions of DNA resulting in the addition or subtraction of repeat units. This slippage error is normally corrected by the MMR system [108]. Due to the prevalence of MSI in HNPCC patients, MSI testing is now recommended for patients suspected of having HNPCC [106]. Microsatellite markers have been described that provide specific, sensitive determination of MSI status in tumors. The results of various MSI studies have revealed two classes of MSI status in tumors, designated MSI-high (MSI in > 20% of markers tested) and MSI-low (MSI in ≤ 20% of markers tested) [106]. Some observed differences in molecular genetics between MSI-high and MSI-low tumors suggest these may be two different types of disease [109-111]. Whether MSI-low tumors are distinct from microsatellite stable cancers, however, is still a question [106].

The discovery of high levels of MSI in HNPCC tumors led researchers who studied the MMR system in lower organisms to search the HNPCC disease locus on chromosome 2p for a MMR gene. The first MMR gene hMSH2 was soon identified and found mutated in HNPCC patients [112,113]. The following year, a second MMR gene hMLH1 was identified and mutations discovered in HNPCC patients [114,115]. In total, seven genes have been identified as members of the human MMR system, however, the vast majority of HNPCC families have mutations in either hMSH2 or hMLH1 [116] (Table 2). Mutations of a third MMR gene hMSH6 have been identified in about 9% of cases [117], while rare cases of mutations in the MMR genes PMS1 and PMS2 have been reported [118,119].

Table 2.

Human Mismatch Repair Genes and HNPCC

HNPCC is usually caused by the inheritance of one mutant MMR allele and LOH at the remaining wild-type allele leading to tumorigenesis in mid-adulthood. However, one study identified three children within an HNPCC pedigree that were diagnosed with hematological malignancies before the age of 3 [120]. It was determined that both parents were heterozygous for a mutation in hMLH1 and the offspring inherited two mutant alleles. Thus, the appearance of hematological disorders within the spectrum of HNPCC appeared to associate with a constitutional loss of MMR function similar to that described in mouse models of HNPCC which carry homozygously mutated MMR alleles [121]. Independently, a second group identified two sisters from another large HNPCC kindred that were homozygous for a missense mutation in hMLH1 and were diagnosed with non-Hodgkin malignant lymphoma and acute myeloid leukemia at ages 2 and 6, respectively [122]. In the last several years, multiple studies have reported similar observations of childhood malignancies including chronic myeloid leukemias, T-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia and non-Hodgkin’s malignant lymphomas associated with mutations in each of the major MMR genes, hMLH1, hMSH2, hMSH6 and hPMS2, including both homozygous mutations as well as compound heterozygous mutations [123-125]. The change in tumor spectrum in patients who inherit two faulty copies of a MMR gene is of interest and may offer clues as to the mechanism driving tissue specificity.

The presence of MSI in 15-40% of sporadic colon, endometrial, ovarian and upper urinary tract cancers indicates that MMR function is disrupted in sporadic tumors as well [126-129]. However, the majority of these tumors are not caused by mutations in the MMR genes, but rather an epigenetic defect resulting in promoter hypermethylation and downregulation of hMLH1 [130-133]. Sporadic MSI-high tumors share similar features with HNPCC tumors, though some clear phenotypic as well as molecular differences exist [134]. Among these phenotypic differences, the sporadic lesions appear to arise via a serrated polyp precursor as opposed to the typical adenoma carcinoma sequence [135]. The serrated lesion gives rise to tumors marked by an MSI-high phenotype, increased promoter methylation including of hMLH1, and increased mutations of the BRAF serine/threonine kinase; the latter two being molecular events not typically associated with HNPCC tumors.

6. The Role of the MMR Genes in Tumorigenesis

6.1 The Mutator Phenotype

Researchers initially hypothesized that loss of MMR contributed to tumorigenesis by creating a cell that accumulated further mutations at an increased rate [136]. Thus, loss of MMR did not lead to a direct growth advantage, as with classical tumor suppressors, rather, it increased the likelihood that other proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressors would be mutated. This idea supported the mutator phenotype hypothesis suggested by Lawrence Loeb in 1974 [137]. Consistent with a mutator hypothesis, human cell lines marked by MSI display an increased frequency of frameshift mutations within a small repeat in the coding region of the type II TGFβ receptor gene [138]. Many labs have since identified mutations in small repeats within the coding regions of numerous genes in MMR-defective cancers, suggesting this is indeed a general mechanism of promoting tumorigenesis. However, due to the high level of repeat instability in these tumors, it is not necessarily clear whether the subsequent mutations in other genes are contributory to tumor phenotype or whether they are carried along for the ride as passenger mutations [139].

6.2 Non-Repair Functions of the MMR Pathway

In addition to functioning in DNA repair, the MMR proteins are also necessary for the activation of cell cycle checkpoints and apoptosis in response to certain DNA damaging agents. MMR-deficient tumor cell lines and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from Msh2, Mlh1 and Msh6 knockout mice are resistant to treatment with certain DNA damaging agents such as cisplatin and N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) [140-143]. Interestingly, these are the three MMR genes most responsible for HNPCC suggesting a selection for the loss of MMR-dependent checkpoints/apoptosis during tumorigenesis. Checkpoint defects in the G2 and G1/S phase of the cell cycle have been observed in hMSH2- and hMLH1-defective tumor cells that are both p53-dependent and independent [144-148]. The damaging agents that generate the most potent MMR-dependent response generate adducts in the DNA that are often mispaired by the replicative polymerase during the next round of S-phase. Interestingly, the cell cycle arrest following damage typically occurs in the second G2 phase after exposure [149]. Two models have emerged to describe the mechanism underlying this observation. The ‘futile cycle’ model proposes that the MMR proteins recognize and attempt to repair the mismatch generated in the first cell cycle, however, they do not actually repair the original adduct caused by the damaging agent [150]. Thus, multiple cycles of excision and repair ensue eventually leading to single-strand breaks in the DNA. During the next round of DNA replication, those single-strand breaks are converted to double-strand breaks which activate a damage checkpoint and ultimately lead to cell death. A second model proposes that the MMR proteins, when bound to the DNA, directly signal to damage signaling molecules such as ATR, ATM, Chk1 and Chk2 [150], though it is not clear why this mechanism would result in checkpoint activation following the second round of DNA replication.

Loss of MMR checkpoint function may provide a direct growth or survival advantage in vivo in certain environments that could provide the basis for selection of a stem cell that loses its wild-type MMR allele during tumorigenesis [151,152]. Interestingly, two mouse lines have been created with missense mutations in either Msh2 or Msh6 that result in cells deficient in mismatch repair, but proficient in cisplatin-induced cell death - effectively separating the repair and damage response functions of the MMR pathway [153,154]. Both mouse lines still develop tumors, however, the onset of tumorigenesis is delayed. This result may suggest that, though the development of a mutator phenotype is sufficient to drive tumorigenesis, the ability of MMR defective cells to survive under conditions of increased damage may accelerate the process. This mechanism may become even more pertinent in the human disease where a MMR defective cell that arises spontaneously would compete against other stem cells in a niche that are still MMR proficient. This competition dynamic would not occur in the mouse models of HNPCC as they are either homozygous for the mutation or, in the case of the Msh6 missense mutant line, the mutation acts as a dominant negative. The role of the MMR pathway in damage-dependent cell killing may also underlie the observation that patients with MMR-defective tumors do not respond as well to certain forms of chemotherapy [155-158].

MMR proteins also play a role in homologous recombination (HR) fidelity, potentially through at least two different mechanisms [159]. First, MMR proteins correct mismatches that arise in recombination intermediates leading to gene conversion. Mutants of msh2, mlh1, or pms1 in yeast display decreased gene conversion events [160-162]. Second, the MMR pathway can play a more dramatic role in blocking the recombination event between two non-identical sequences. In normal cells, the efficiency of recombination between homeologous sequences (~10% divergence) is reduced, however, in cells deficient for MMR, homeologous sequences recombine nearly as efficiently as homologous sequences. The MMR proteins may prevent the formation of heteroduplex DNA that contains a large number of mismatches during HR [163] and possibly limit branch migration in the presence of increased heteroduplex sequence [161]. The determination as to whether the MMR proteins simply repair the consequential mispairs or abort the entire process likely depends on the level of divergence between the recombining sequences [159]. In a process that may be related, the MMR proteins have also been shown to play a role in maintaining telomere length [164]. Experiments in yeast have shown that defects in MMR result in enhanced telomerase-free survival possibly due to increased telomeric recombination. Additionally, Mlh1 has been shown to be required for normal meiosis in mice [165,166]. In yeast, MutL homologs similarly play a role in promoting crossovers during meiosis [167,168].

Mouse models of HNPCC have revealed an additional role for MMR proteins in the process of somatic hypermutability at the immunoglobulin (Ig) loci in B cells [169,170]. The degree of somatic mutation within the variable region of the Ig loci in MMR-deficient mouse models is reduced possibly implicating the MMR enzymes in a process that increases mutation frequency. Two possible models have emerged for this function. First, a spontaneous mutation occurs, possibly through the activation induced cytidine deaminase (AID), that results in a DNA mismatch. When the MMR system attempts to correct this mismatch, it corrects the nucleotide in the parental strand instead of the template strand, resulting in fixation of the mutation. Second, in the process of correcting a spontaneous mismatch, the MMR proteins recruit an error-prone polymerase such as pol η resulting in secondary mutations in the repaired region [170,171]. In attempt to process a DNA mismatch within the variable region of the Ig loci, the MMR proteins may also be contributing to the class-switch process as loss of MMR results in reduced class-switch recombination [172]. It has been proposed that the combination of AID and the uracil DNA glycosylase result in multiple single-strand nicks throughout the region that are converted to double-strand breaks during the MMR strand excision and resynthesis steps. These double-strand breaks are necessary for instigation of DNA recombination. Though it is tempting to speculate an association between the role of MMR in class switch recombination and cancer, that role is not immediately intuitive as the proposed mechanism would suggest that loss of MMR would reduce the chances of aberrant recombination events that may cause cancer.

7. MMR gene mutations in HNPCC

7.1 Germline Missense Variants in the MMR Genes

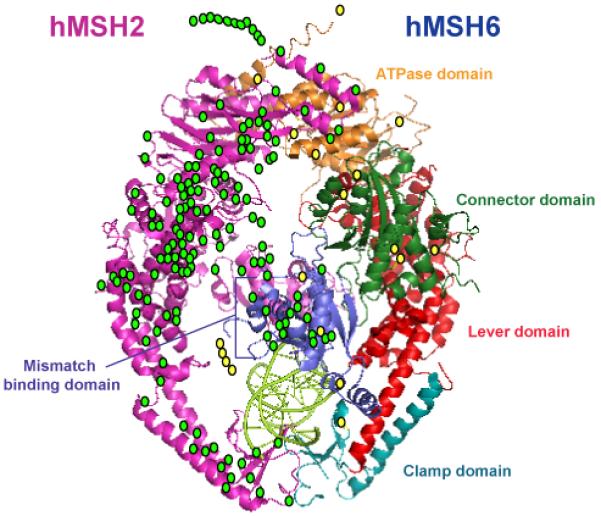

The majority of MMR gene mutations in the germline of HNPCC patients are nonsense or frameshift mutations that result in a truncated protein, or more commonly, no protein product in the cell [116]. Unlike with APC, there do not appear to be partial functions for truncated MMR proteins. Examination of the crystal structures of human MSH2 and MSH6 [173] or bacterial MutL [174] (the hMLH1 homolog) suggest that crucial domains that must be coordinated for proper protein function exist at opposite ends of the molecule (see Figure 2). In addition, many prematurely truncated protein products are likely unstable in the cell as loss of protein expression as determined by immunohistochemistry is commonly observed in HNPCC tumors [175]. For this reason, immunohistochemical analysis of the four major MMR proteins; hMLH1, hMSH2, hMSH6 and hPMS2 is often used, in addition to MSI testing, during screening of CRCs for HNPCC. Therefore, the pathogencity of these germline nonsense and frameshift mutations is often assumed. However, a substantial number of patients that fulfill the Bethesda or Amsterdam criteria for HNPCC (or close enough to fulfilling the criteria to warrant suspicion) carry germline missense variations in one of their MMR genes. Approximately 17% of mutations identified in hMSH2 [116], 31% of mutations in hMLH1 [116] and 45% of mutations in hMSH6 [176] result in single amino acid alterations. The significance of these alterations to pathogenesis is less clear. The mutations are found throughout the length of the MMR proteins with no apparent “hot spots” within known functional domains (Figure 2). The ability to determine the likelihood that these missense variants contribute to disease phenotype will have consequences for the management of the patient, as their risk of future cancers would be increased. In addition, family members who carry the same germline variant will also need to be managed differently depending upon the significance of the variant. Thus, determining the relevance of these variations is an important challenge.

Fig. 2.

HNPCC-associated missense mutations of hMSH2 and hMSH6. The location of HNPCC-associated missense mutations in hMSH2 (green circles) and hMSH6 (yellow circles) are mapped to the crystal structure of the hMSH2-hMSH6 heterodimer [172]. Mutations that do not overlay directly onto the crystal structure represent mutations in regions of the proteins that were removed prior to crystallography. The hMSH2 subunit is labeled in pink, while the hMSH6 subunit is labeled by sub-domain.

7.2 Functional Analyses of MMR Variants

A prediction can be made for the significance of a variant based on its association with disease, its absence from disease-free controls and the type of amino acid change it would encode. However, the ability to determine whether the variant disrupts some aspect of MMR function may provide the best evidence of its pathogenicity. To that end, a number of studies have accumulated over the last several years examining the functional consequences of missense variants in the four major MMR genes. The assays utilized can generally be divided into cell-based assays using either human cells or yeast and in vitro biochemical analyses. Examining the ability of a variant-containing MMR protein to participate in the correction of a DNA mismatch has been performed using in vivo repair assays in yeast. The power of yeast genetics allows for the relatively easy creation of strains carrying different MMR genotypes. These mutant strains can then be tested for the level of instability in homopolymeric runs in marker genes that provide a measurable phenotype. Initial studies expressed human MSH2 and MSH6 in wild-type yeast resulting in a 4000-fold increase in the mutation rate in a reporter gene [177]. The interpretation of this result was that the human proteins bind to mismatched DNA and interfere with the ability of the yeast MMR system to correct the mismatch. However, expression of hMSH6 in conjunction with an HNPCC-associated variant of hMSH2 (R524P) does not affect the mutation rate suggesting that this variant-containing heterodimer is incapable of binding to mismatched DNA and, thus, unable to interfere with the endogenous yeast MMR system. Similarly, expression of human MLH1 in a MMR-proficient yeast strain results in a 5-80 fold increased mutation rate depending on the reporter used by acting in a dominant negative fashion [178]. The authors went on to demonstrate that 16 of 18 HNPCC associated variants of hMLH1 fail to produce a similar dominant mutator phenotype. Reduced expression was observed for some of the variants suggesting the alteration may affect protein stability, however, the remaining variants may directly interfere with protein function.

Some disease associated residues in the human protein are conserved in yeast as the degree of sequence identity between yeast and human MMR proteins is quite high. Thus, numerous studies have tested yeast strains expressing missense mutations in the yeast MMR gene that are analogous to the human disease-associated variant. Disruption of the wild-type yeast MSH2 gene results in a 290-fold increase in repeat tract instability that can be rescued by re-expression of the missing wild-type allele from a plasmid [179]. A plasmid-expressed MSH2 carrying a P640L mutation (equivalent to the P622L variant identified in a human patient [113]) failed to complement the knockout. An examination of yeast strains carrying the equivalent of 7 missense variants of MSH2 concluded that all 7 failed to restore normal repair activity in an msh2 strain [180]. When the variants were expressed in an MSH2 proficient strain, all but the R524P- and P622L-equivalent variants acted in a dominant-negative fashion suggesting that variants can disrupt MMR function via multiple mechanisms. In a more recent large-scale study, 54 missense variants of MSH2 were engineered in yeast and examined for their ability to restore repair capacity to an msh2Δ strain [181]. Thirty-three of the variants displayed defective repair compared to a wild-type control, while three showed an intermediate phenotype. A study of 28 MLH1 variants determined that 15 were either null or defective for MMR activity [182]. Interestingly, however, when the same variants were tested in a similar repair assay in a different yeast strain, there were a number of differences in the mutation rate suggesting that the functional effects of some variants may depend upon genetic background. This finding reveals the complication of interpreting analyses of human MMR variants in yeast.

Attempts have also been made to study the effect of variants on MMR function in human cell culture models. Seven disease-associated variants and two known polymorphisms of hMLH1 were expressed in 293T cells which lack endogenous hMLH1 expression due to promoter hypermethylation [183]. Extracts from these cells were mixed with a plasmid containing a lacZ gene with a G/T mismatch. Transformation of the plasmid into E. coli results in an increase in single color colonies if the repair has occurred as opposed to the mixed blue-white colonies that appear in the absence of repair [184]. The study revealed that four of seven hMLH1 variants fail to restore MMR capability to the extracts to the same extent as wild-type hMLH1, while 3 variants and the two polymorphisms restore normal repair activity. Furthermore, two of the failed variants, T117M and K618T, affect the stability of the hMLH1 protein in the cell [183]. A more recent examination of 101 hMLH1 variants expressed in hMLH1-defective HCT116 cells revealed 50 variants that have less than 60% of the wild-type repair activity leading the authors to conclude they were MMR deficient [185]. A similar study was performed examining fifteen variants of hMSH2 expressed in hMSH2-deficient LoVo cancer cells and tested for their ability to heterodimerize with hMSH6 [186]. Extracts from these cells were then used in an in vitro MMR assay which examines the ability of the extracts to repair a G/T mismatch that resides within a specific restriction site in circular duplex DNA. Correction of the mismatch results in restoration of the restriction site [187]. The authors conclude that, though none of the variants tested affected interaction with hMSH6, 12 of the variants were defective in the MMR assay suggesting pathogenicity.

In addition to being used for repair assays, human cell expression systems have allowed for the examination of MMR variant protein localization in the cell. An inability of the MMR proteins to properly localize to the nucleus would have obvious consequences for their function. The first variants demonstrated to affect nuclear localization are hMSH2 P622L and C697F, which, when fused to YFP, remain mostly in the cytoplasm compared to wild-type hMSH2-YFP [188,189]. Three additional missense variants of hMSH2 were fused to EGFP and examined for nuclear localization [190]. The G162R and R359S variants affect the proper localization of hMSH2 in 293 cells suggesting these variants may be pathogenic.

A number of studies have examined the function of the recombinant variant MMR proteins using in vitro biochemical assays. The ability of recombinant variant MMR proteins to restore repair function to deficient cellular extracts using the MMR assays described above have been examined in four separate studies [191-194]. These reports investigated variants in hMSH2, hMSH6 and hMLH1 demonstrating that the majority of variants tested failed to restore repair activity to the same extent as the wild-type protein. While use of the in vitro MMR assay provides an overall examination of the variants ability to repair a DNA mismatch, recombinant versions of variant MMR proteins have also been utilized to test individual steps in the biochemical mechanism of MMR. An examination of the ability of 6 different hMSH2 variants to effect formation of a heterodimer with hMSH3 or hMSH6 was carried out using in vitro transcription and translation to express the fragments of hMSH2 containing the altered amino acid. These fragments were then tested in a glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown assay for their ability to interact with a full-length GST-tagged hMSH3 or hMSH6 [195]. None of the variants affect interactions with either heterodimer partner. A similar approach was taken to examine 11 variants of hMLH1 and their ability to interact with their heterodimer partner, hPMS2 [196]. In this study, six variants had a significant effect on hPMS2 interaction, three had intermediate effects while two variants had no effect. Ten of the variants, including the two that had no effect on the interaction, localize to a domain of hMLH1 implicated as necessary for binding to hPMS2. Our own group has tested several variants of hMSH2 and hMSH6 to determine their effect on multiple steps in the biochemical mechanism of the hMSH2-hMSH6 heterodimer [197,198]. The hMSH2-hMSH6 heterodimer initiates the MMR process by recognizing and binding to single nucleotide mismatches and small insertion/deletion loops (whereas the hMSH2-hMSH3 heterodimer recognizes larger insertion/deletion loops) [199]. Upon mismatch binding, the hMSH2-hMSH6 proteins, both ATP-binding cassette-type ATPases, exchange ADP for ATP provoking a conformational change that likely allows for the recruitment of hMLH1-hPMS2. This tetramer, through an as of yet undetermined mechanism, facilitates the loading of an exonuclease to excise the mismatch-containing daughter strand. The hydrolysis of ATP by hMSH2-hMSH6, which is essential for MMR [200], may be involved in recycling the complex to its initial state [201]. Using purified, recombinant hMSH2-hMSH6, we tested the ability of variant containing heterodimers to bind to a G/T mismatch, bind to ATP, exchange ADP for ATP and hydrolyze ATP in a mismatch-dependent fashion. While 6 of 7 hMSH2 variants simultaneously affect the ability of the heterodimer to bind to a mismatch and hydrolyze ATP in a mismatch-dependent manner [198], the results for 7 hMSH6 single amino-acid alterations are more varied [197]. Two of seven hMSH6 variants behave similarly to wild-type in all assays tested. Two variants affect both mismatch binding and ATPase activity, while three of the variants affect mismatch-stimulated ATPase without affecting mismatch recognition. These three variants (hMSH6 G566R, D803G and V878A) may effectively uncouple the ATPase activity from mismatch recognition. These results are interesting clinically as they suggest that 6 of the 7 hMSH6 variants affect ATPase function and, therefore, may be pathogenic. However, they are also potentially interesting as tools to further probe the normal mechanism of the hMSH2-hMSH6 heterodimer. By using cancer-associated missense variants of the MMR proteins to reveal the ways in which tumors select to disrupt MMR function, we may gain insight into the normal MMR process.

Similar to the APC gene, missense and silent variants in the MMR genes may also affect splicing of the mRNA. An analysis of the RNA from 7 HNPCC patients, including 5 patients carrying a missense variant in hMLH1 and 2 patients carrying a missense variant in hMSH2, demonstrated that three of the mutations, all in hMLH1, affected RNA splicing [202]. An examination of RNA expression from 19 patients carrying missense or silent variants in hMLH1 or hMSH2 revealed that 10 of the 19 resulted in exon skipping or activation of cryptic splice sites [203]. A third study identified fifteen of sixty missense or silent variations in exonic or intronic regions of hMLH1 or hMSH2 that resulted in aberrant splicing [204]. These combined results make it clear that one must also consider the effect of missense variants on mRNA as well as protein when predicting an effect on pathogencity.

No single assay has emerged that can clearly assign causality to any disease-associated variant. Though the various assays described do provide strong evidence for the role of a given variant in pathogenesis, each assay is tedious and is not terribly practical in a clinical setting. A growing number of variants have been tested, yet over 500 variants in the four major MMR genes have been described and new ones are likely to be discovered [205]. A new database has been established by the International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumors (InSIGHT) which details variants that have been tested with different functional assays and the results of those studies [206]. This resource should help the research community in the classification of the missense variants. What is the best protocol for testing these variants continues to be discussed (see also [206,207]) including a proposed decision tree that involves a combination of in vitro repair assays followed up by other cellular-based assays, if necessary, to thoroughly characterize each variant [208]. The proposed protocol also looks to take advantage of in silico methods to analyze variant contribution to phenotype. A recently described bioinformatics algorithm entitled Multivariate Analysis of Protein Polymorphisms-Mismatch Repair (MAPP-MMR) may assist in classifying MMR variants as either deleterious or neutral [209]. The MAPP-MMR algorithm considers the evolutionary relationship in the protein sequence at each amino acid residue in a multisequence alignment of MMR gene orthologs. Each sequence position is also examined for the physiochemical properties of the amino acid in order to assign a score for how dissimilar a variant may be from the original amino acid. Using MAPP-MMR, the authors classified over 300 missense variants in either hMLH1 or hMSH2. They report a high accuracy of classification based on a series of validation criteria to determine the nature of the variant. In order to be considered deleterious, the variant must occur in a proband that has either early onset CRC or a first-degree relative who does. In addition, two or more of the following criteria must be met: i) the variant must co-segregate with the disease in ≥ 1 family member; ii) functional evidence exists that the variant disrupts an aspect of MMR; or iii) molecular epidemiology evidence linking the variant with increased CRC risk in ≥ 2 nonoverlapping groups. The authors report the sensitivity of the algorithm at 94% with specificity at 96%. Bioinformatics tools such as MAPP-MMR may help identify those variants which would warrant further functional analysis.

8. Beyond the First Hit

The association between germline mutations in APC or one of the MMR genes and colon cancer development in FAP patients and HNPCC patients, respectively, is well established. Yet there remain fundamental questions concerning the relationship between genotype and phenotype in these cancers. An understanding of the relationship between location of an APC mutation and phenotype or determining whether a germline missense variant in an MMR gene contributes to pathogenicity would enhance our ability to effectively use these genes as targets for diagnosis, prevention or treatment in these patients. That these issues remain so challenging for two well-studied diseases with well-established genetic bases underscores the difficulties ahead in unraveling the significance of novel variants in other genes in colon tumors that have been found [1,2] and will surely be found in the future. We are entering an era where we may begin to get a handle on the number of mutations in human tumors, but deciphering which of those alterations are necessary for tumor phenotype will still be an enormous undertaking.

An initial study of colon and breast cancers revealed that individual tumors harbor ~ 80 mutations [1]. A follow-up validation screen of more tumor samples combined with a determination of the number of mutations per nucleotide sequenced for a given gene led to the conclusion that only 15 or less of those mutations were actually driving key phenotypical changes in the tumor [2]. The remaining variants identified may possibly be passenger mutations that do not provide any selective advantage to the tumor, but rather come along for the ride during clonal expansion with another mutation that did affect phenotype. Similar sequencing approaches have been taken to identify mutations in human malignant glioblastomas [5] and lung adenocarcinomas [4]. These studies have focused on sequencing the coding regions from candidate genes and have provided a wealth of information regarding mutations in cancer. More recently, massively parallel sequencing technology was used to “deep sequence” an entire tumor genome from a patient suffering acute myeloid leukemia [3]. The authors identified over 62,000 tumor-specific single nucleotide variants. They further considered 181 variants that were within the coding regions of genes and were non-synonymous or predicted to interfere with splice junctions. Further validation testing reduced the number to 8 single nucleotide variants and 2 small insertion mutations discovered in the tumor. Eight of the ten genes affected are genes whose role in tumor formation is not clear, suggesting that this sequencing approach may identify new genes involved in human cancers.

This improved sequencing technology illustrates the enormous genetic complexity of cancer, but also may provide the best hope for tackling this complexity. A combination of improved sequencing techniques and statistical analyses will be useful in identifying genes that may be involved in cancer. However, these approaches will likely only produce candidate genes requiring further functional testing to determine their contribution to tumorigenesis. As seen even for diseases as well characterized as FAP and HNPCC, the manner in which a variation affects phenotype is not always straightforward. The good news, however, is that these efforts should lead to new targets for treatment. This information may also better prepare us for the day when sequencing everyone’s genome becomes routine and a large number of variants of uncertain significance will be uncovered in the germline of individual patients. These variants may hold clues to cancer risk, leading to an era of medicine where genetic information is no longer used to treat cancer, but rather used to prevent it in the first place.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Dr. Henry Furneaux for helpful comments. This work was supported in part by NIH grant CA115783.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sjoblom T, Jones S, Wood LD, Parsons DW, Lin J, Barber TD, Mandelker D, Leary RJ, Ptak J, Silliman N, Szabo S, Buckhaults P, Farrell C, Meeh P, Markowitz SD, Willis J, Dawson D, Willson JKV, Gazdar AF, Hartigan J, Wu L, Liu C, Parmigiani G, Park BH, Bachman KE, Papadopoulos N, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, Velculescu VE. The Consensus Coding Sequences of Human Breast and Colorectal Cancers. Science. 2006;314:268–274. doi: 10.1126/science.1133427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, Lin J, Sjoblom T, Leary RJ, Shen D, Boca SM, Barber T, Ptak J, Silliman N, Szabo S, Dezso Z, Ustyanksky V, Nikolskaya T, Nikolsky Y, Karchin R, Wilson PA, Kaminker JS, Zhang Z, Croshaw R, Willis J, Dawson D, Shipitsin M, Willson JKV, Sukumar S, Polyak K, Park BH, Pethiyagoda CL, Pant PVK, Ballinger DG, Sparks AB, Hartigan J, Smith DR, Suh E, Papadopoulos N, Buckhaults P, Markowitz SD, Parmigiani G, Kinzler KW, Velculescu VE, Vogelstein B. The Genomic Landscapes of Human Breast and Colorectal Cancers. Science. 2007;318:1108–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ley TJ, Mardis ER, Ding L, Fulton B, McLellan MD, Chen K, Dooling D, Dunford-Shore BH, McGrath S, Hickenbotham M, Cook L, Abbott R, Larson DE, Koboldt DC, Pohl C, Smith S, Hawkins A, Abbott S, Locke D, Hillier LW, Miner T, Fulton L, Magrini V, Wylie T, Glasscock J, Conyers J, Sander N, Shi X, Osborne JR, Minx P, Gordon D, Chinwalla A, Zhao Y, Ries RE, Payton JE, Westervelt P, Tomasson MH, Watson M, Baty J, Ivanovich J, Heath S, Shannon WD, Nagarajan R, Walter MJ, Link DC, Graubert TA, DiPersio JF, Wilson RK. DNA sequencing of a cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukaemia genome. Nature. 2008;456:66–72. doi: 10.1038/nature07485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, Mardis ER, McLellan MD, Cibulskis K, Sougnez C, Greulich H, Muzny DM, Morgan MB, Fulton L, Fulton RS, Zhang Q, Wendl MC, Lawrence MS, Larson DE, Chen K, Dooling DJ, Sabo A, Hawes AC, Shen H, Jhangiani SN, Lewis LR, Hall O, Zhu Y, Mathew T, Ren Y, Yao J, Scherer SE, Clerc K, Metcalf GA, Ng B, Milosavljevic A, Gonzalez-Garay ML, Osborne JR, Meyer R, Shi X, Tang Y, Koboldt DC, Lin L, Abbott R, Miner TL, Pohl C, Fewell G, Haipek C, Schmidt H, Dunford-Shore BH, Kraja A, Crosby SD, Sawyer CS, Vickery T, Sander S, Robinson J, Winckler W, Baldwin J, Chirieac LR, Dutt A, Fennell T, Hanna M, Johnson BE, Onofrio RC, Thomas RK, Tonon G, Weir BA, Zhao X, Ziaugra L, Zody MC, Giordano T, Orringer MB, Roth JA, Spitz MR, Wistuba II, Ozenberger B, Good PJ, Chang AC, Beer DG, Watson MA, Ladanyi M, Broderick S, Yoshizawa A, Travis WD, Pao W, Province MA, Weinstock GM, Varmus HE, Gabriel SB, Lander ES, Gibbs RA, Meyerson M, Wilson RK. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC-H, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, Mankoo P, Carter H, Siu I-M, Gallia GL, Olivi A, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Keir S, Nikolskaya T, Nikolsky Y, Busam DA, Tekleab H, Diaz LA, Jr., Hartigan J, Smith DR, Strausberg RL, Marie SKN, Shinjo SMO, Yan H, Riggins GJ, Bigner DD, Karchin R, Papadopoulos N, Parmigiani G, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW. An Integrated Genomic Analysis of Human Glioblastoma Multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rustgi A. The genetics of hereditary colon cancer. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2525–38. doi: 10.1101/gad.1593107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burt RW. Polyposis Syndromes. In: Yamada T, Alpers DH, Owyang C, Powell DW, Silverstein FE, editors. Textbook of Gastroenterology. Vol. 2. J. B. Lippincott Company; Philadelphia: 1991. pp. 1674–1696. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lynch HT, Lynch JF. Genetics of colonic cancer. Digestion. 1998;59:481–92. doi: 10.1159/000007525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, Vogelstein B. Clonal analysis of human colorectal tumors. Science. 1987;238:193–7. doi: 10.1126/science.2889267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrera L, Kakati S, Gibas L, Pietrzak E, Sandberg AA. Gardner syndrome in a man with an interstitial deletion of 5q. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1986;25:473–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320250309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodmer WF, Bailey CJ, Bodmer J, Bussey HJ, Ellis A, Gorman P, Lucibello FC, Murday VA, Rider SH, Scambler P. Localization of the gene for familial adenomatous polyposis on chromosome 5. Nature. 1987;328:614–6. doi: 10.1038/328614a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leppert M, Dobbs M, Scambler P, O’Connell P, Nakamura Y, Stauffer D, Woodward S, Burt R, Hughes J, Gardner E, et al. The gene for familial polyposis coli maps to the long arm of chromosome 5. Science. 1987;238:1411–3. doi: 10.1126/science.3479843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura Y, Lathrop M, Leppert M, Dobbs M, Wasmuth J, Wolff E, Carlson M, Fujimoto E, Krapcho K, Sears T, et al. Localization of the genetic defect in familial adenomatous polyposis within a small region of chromosome 5. Am J Hum Genet. 1988;43:638–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joslyn G, Carlson M, Thliveris A, Albertsen H, Gelbert L, Samowitz W, Groden J, Stevens J, Spirio L, Robertson M. Identification of deletion mutations and three new genes at the familial polyposis locus. Cell. 1991;66:601–13. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groden J, Thliveris A, Samowitz W, Carlson M, Gelbert L, Albertsen H, Joslyn G, Stevens J, Spirio L, Robertson M. Identification and characterization of the familial adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Cell. 1991;66:589–600. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powell SM, Zilz N, Beazer-Barclay Y, Bryan TM, Hamilton SR, Thibodeau SN, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. APC mutations occur early during colorectal tumorigenesis. Nature. 1992;359:235–7. doi: 10.1038/359235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith KJ, Johnson KA, Bryan TM, Hill DE, Markowitz S, Willson JK, Paraskeva C, Petersen GM, Hamilton SR, Vogelstein B. The APC gene product in normal and tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2846–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jass J, Whitehall V, Young J, Leggett B. Emerging concepts in colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:862–876. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka K, Oshimura M, Kikuchi R, Seki M, Hayashi T, Miyaki M. Suppression of tumorigenicity in human colon carcinoma cells by introduction of normal chromosome 5 or 18. Nature. 1991;349:340–2. doi: 10.1038/349340a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goyette MC, Cho K, Fasching CL, Levy DB, Kinzler KW, Paraskeva C, Vogelstein B, Stanbridge EJ. Progression of colorectal cancer is associated with multiple tumor suppressor gene defects but inhibition of tumorigenicity is accomplished by correction of any single defect via chromosome transfer. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1387–95. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groden J, Joslyn G, Samowitz W, Jones D, Bhattacharyya N, Spirio L, Thliveris A, Robertson M, Egan S, Meuth M. Response of colon cancer cell lines to the introduction of APC, a colon-specific tumor suppressor gene. Cancer Research. 1995;55:1531–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubinfeld B, Souza B, Albert I, Muller O, Chamberlain SH, Masiarz FR, Munemitsu S, Polakis P. Association of the APC gene product with beta-catenin. Science. 1993;262:1731–4. doi: 10.1126/science.8259518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su LK, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Association of the APC tumor suppressor protein with catenins. Science. 1993;262:1734–7. doi: 10.1126/science.8259519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peifer M, Sweeton D, Casey M, Wieschaus E. wingless signal and Zeste-white 3 kinase trigger opposing changes in the intracellular distribution of Armadillo. Development. 1994;120:369–80. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Funayama N, Fagotto F, McCrea P, Gumbiner BM. Embryonic axis induction by the armadillo repeat domain of beta- catenin: evidence for intracellular signaling. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:959–68. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.5.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McMahon AP, Moon RT. Ectopic expression of the proto-oncogene int-1 in Xenopus embryos leads to duplication of the embryonic axis. Cell. 1989;58:1075–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90506-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Behrens J, von Kries JP, Kuhl M, Bruhn L, Wedlich D, Grosschedl R, Birchmeier W. Functional interaction of beta-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature. 1996;382:638–42. doi: 10.1038/382638a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molenaar M, van de Wetering M, Oosterwegel M, Peterson-Maduro J, Godsave S, Korinek V, Roose J, Destree O, Clevers H. XTcf-3 transcription factor mediates beta-catenin-induced axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell. 1996;86:391–9. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He TC, Sparks AB, Rago C, Hermeking H, Zawel L, da Costa LT, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science. 1998;281:1509–12. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tetsu O, McCormick F. Beta-catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature. 1999;398:422–6. doi: 10.1038/18884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van de Wetering M, Sancho E, Verweij C, de Lau W, Oving I, Hurlstone A, van der Horn K, Batlle E, Coudreuse D, Haramis AP, Tjon-Pon-Fong M, Moerer P, van den Born M, Soete G, Pals S, Eilers M, Medema R, Clevers H. The beta-Catenin/TCF-4 Complex Imposes a Crypt Progenitor Phenotype on Colorectal Cancer Cells. Cell. 2002;111:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munemitsu S, Albert I, Souza B, Rubinfeld B, Polakis P. Regulation of intracellular beta-catenin levels by the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor-suppressor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3046–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korinek V, Barker N, Morin PJ, van Wichen D, de Weger R, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Clevers H. Constitutive transcriptional activation by a beta-catenin-Tcf complex in APC-/- colon carcinoma. Science. 1997;275:1784–7. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubinfeld B, Albert I, Porfiri E, Fiol C, Munemitsu S, Polakis P. Binding of GSK3beta to the APC-beta-catenin complex and regulation of complex assembly. Science. 1996;272:1023–6. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neufeld KL, Zhang F, Cullen BR, White RL. APC-mediated downregulation of beta-catenin activity involves nuclear sequestration and nuclear export. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:519–23. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sierra J, Yoshida T, Joazeiro CA, Jones KA. The APC tumor suppressor counteracts beta-catenin activation and H3K4 methylation at Wnt target genes. Genes Dev. 2006;20:586–600. doi: 10.1101/gad.1385806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong MH, Hermiston ML, Syder AJ, Gordon JI. Forced expression of the tumor suppressor adenomatosis polyposis coli protein induces disordered cell migration in the intestinal epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9588–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sansom OJ, Reed KR, Hayes AJ, Ireland H, Brinkmann H, Newton IP, Batlle E, Simon-Assmann P, Clevers H, Nathke IS, Clarke AR, Winton DJ. Loss of Apc in vivo immediately perturbs Wnt signaling, differentiation, and migration. Genes & Development. 2004;18:1385–1390. doi: 10.1101/gad.287404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nathke IS, Adams CL, Polakis P, Sellin JH, Nelson WJ. The adenomatous polyposis coli tumor suppressor protein localizes to plasma membrane sites involved in active cell migration. Journal of Cell Biology. 1996;134:165–79. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.1.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kroboth K, Newton IP, Kita K, Dikovskaya D, Zumbrunn J, Waterman-Storer CM, Nathke IS. Lack of Adenomatous Polyposis Coli Protein Correlates with a Decrease in Cell Migration and Overall Changes in Microtubule Stability. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2007;18:910–918. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-03-0179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su LK, Burrell M, Hill DE, Gyuris J, Brent R, Wiltshire R, Trent J, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. APC binds to the novel protein EB1. Cancer Research. 1995;55:2972–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morrison EE, Askham JM, Markham AF, Meredith DM. EB1, a protein which interacts with the APC tumour suppressor, is associated with the microtubule cytoskeleton throughout the cell cycle. Oncogene. 1998;17:3471–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202247. W.B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]