Abstract

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA) is a common, progressive, and potentially lethal vascular disease. A major obstacle in AAA research, as well as patient care, is the lack of technology that enables non-invasive acquisition of molecular/cellular information in the developing AAA. In this review we will briefly summarize the current techniques (e.g. ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging) for anatomical imaging of AAA. We also discuss the various functional imaging techniques that have been explored for AAA imaging. In many cases, these anatomical and functional imaging techniques are not sufficient for providing surgeons/clinicians enough information about each individual AAA (e.g. rupture risk) to optimize patient management. Recently, molecular imaging techniques (e.g. optical and radionuclide-based) have been employed to visualize the molecular alterations associated with AAA, which are discussed in this review. Lastly, we try to provide a glance into the future and point out the challenges for AAA imaging. We believe that the future of AAA imaging lies in the combination of anatomical and molecular imaging techniques, which are largely complementary rather than competitive. Ultimately, with the right molecular imaging probe, clinicians will be able to monitor AAA growth and evaluate the risk of rupture accurately, so that the life-saving surgery can be provided to the right patients at the right time. Equally important, the right imaging probe will also allow scientists/clinicians to acquire critical data during AAA development and to more accurately evaluate the efficacy of potential treatments.

Keywords: Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), anatomical imaging, functional imaging, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), molecular imaging, positron emission tomography (PET), ultrasound

INTRODUCTION

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), a progressive expansion and weakening of the abdominal aortic wall, is a common and potentially lethal vascular disease [1]. In the United States, there are approximately 15,000 deaths/year related to the rupture of an AAA (http://www.vdf.org/diseaseinfo/aaa/), a mortality rate that rivals that of ovarian cancer or leukemia [2]. AAA is more prevalent in men over the age of 65. However, it affects both adult men and women of all ages and ethnic backgrounds. As our population ages, a rise in the number of AAA cases is expected. Without the development of new effective therapies, AAA could become an even more significant health problem.

Currently, surgical interventions including open surgical and endovascular repair are the only treatment options for AAA patients. Since endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) was first introduced almost 2 decades ago [3], it has gained widespread acceptance as an alternative to open repair for patients with AAA [4]. One of major complications of EVAR is the development of endoleaks, i.e. blood flow outside the endograft but inside the aneurysm sac, which occur in approximately 25% of patients. Although effective in preventing AAA rupture, these surgical procedures are invasive and therefore are reserved for patients with advanced AAA that are prone to rupture, defined as ≥ 5.5 cm in aortic diameter for men and ≥ 5.0 cm for women, respectively.

The recent advances in diagnosis and endovascular treatment of AAA patients would not have been possible without the concomitant development in vascular imaging techniques that enable visualization and characterization of aneurysmal arteries as well as monitoring of their progression or regression. Ultrasonography has rapidly evolved into a cost-effective approach for aneurysm screening (covered under Medicare in the United States) while computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has becoming an integral component of AAA diagnosis and management. However, many challenges still exist in AAA imaging, among which is the inability to accurately identify ruptured-prone AAAs.

Here we provide a brief overview of the established and newly developed techniques for AAA imaging. Although outcomes are still lacking for many of these methods, it is generally believed that vascular imaging will become an indispensable component of a multidisciplinary effort to improve diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of AAAs.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF AAA

The pathogenesis of AAA is complex and multi-factorial. A brief review of the current knowledge of aneurysm pathophysiology is provided here to facilitate the understanding of the recent development in AAA imaging. Histologically, aneurysmal tissues are characterized by disruption of the elastic fibers, the major component of the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the aortic wall. This feature has been consistently duplicated in animal models of AAA [5]. Extensive research effort has been devoted to understanding the mechanism for such elastolytic process in AAA and an elevated expression and/or activity of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) [6], MMP-3 [7,8], MMP-7 [9], MMP-9 [10–12] and MMP-12 [13,14] has been reported in human AAA tissues. In animal models, targeted gene deletion of MMP-9 [15] and/or MMP-2 [16] also protected mice from developing AAA. Therefore, MMP inhibition has been explored for AAA treatment and pilot clinical trials have indicated that the MMP inhibitor, doxycycline, may limit the growth of small AAAs [17,18]. A multi-centered clinical trail has been initiated. Many studies have also suggested that statins can improve the perioperative and long-term outcomes of aneurysm operations as well as reducing the expansion rates [19,20].

Another prominent histological feature of AAA is the extensive transmural infiltration of macrophages and lymphocytes [21]. Depletion of neutrophils, lymphocytes, mast cells, and proinflammatory cytokines impairs aneurysm formation in experimental models [22–25]. The prevailing view is that inflammatory cells, mainly macrophages, are the major source of matrix-degrading enzymes and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Several major pro-inflammatory mediators have been detected in aneurysmal tissues, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and interferon (IFN)-γ [21,26]. A role for monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and its receptor, CCR2, has also been indicated in AAAs [27–29]. Studies have shown that blockade of MCP-1 or deficiency in CCR2 resulted in suppressed AAA formation, associated with a marked decrease in monocyte-mediated vascular inflammation in mice [30,31].

Histological examination of both experimental animal and human AAAs has revealed a paucity of medial smooth muscle cells (SMCs) in these specimens [32–34]. The loss of SMCs could be caused by apoptosis or necrosis [33,35,36], however the precise contribution of SMC apoptosis to AAA development has not been directly addressed experimentally. Equally understudied is the role of surviving vascular SMCs in AAA pathophysiology [37].

ANATOMICAL IMAGING OF AAA

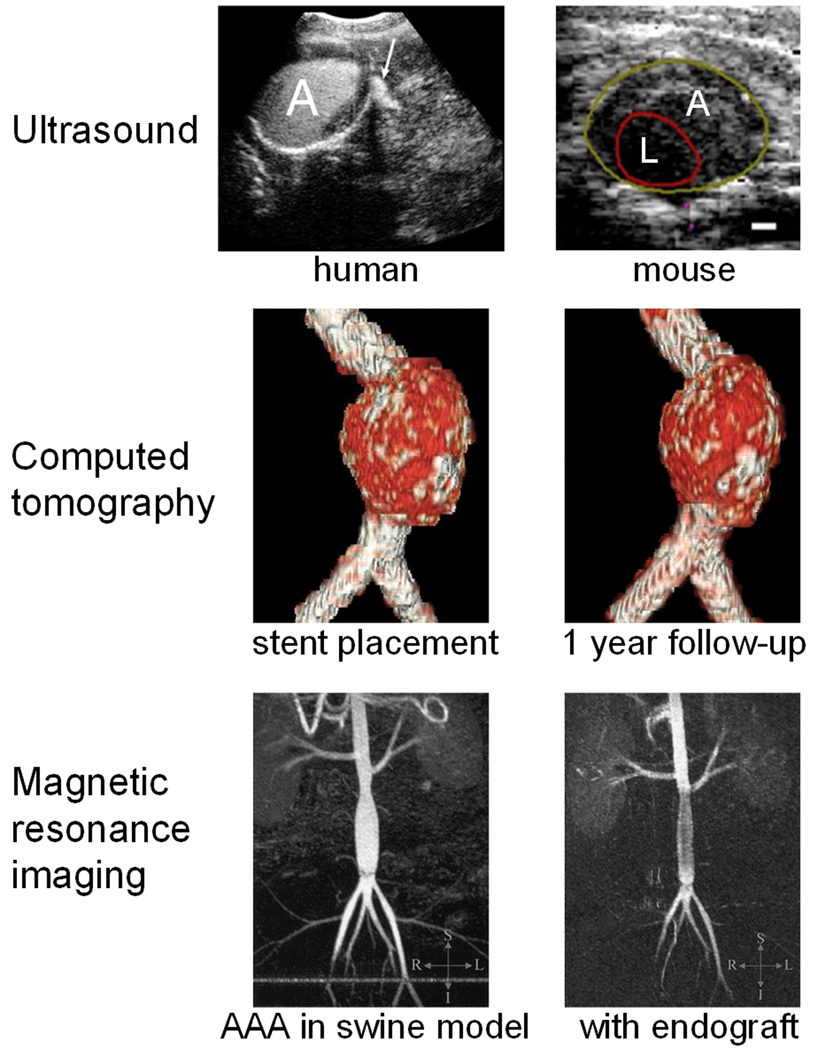

AAA is usually diagnosed by anatomical imaging techniques such as ultrasound, CT, and/or MRI (Figure 1). Comparing with other anatomical imaging techniques, ultrasonography is non-invasive, quick, inexpensive, less technically demanding, and yet quite accurate, all of which are ideal features for routine screening. Several randomized clinical trials, conducted to test the use of ultrasound as a screening modality for AAA, demonstrated that the mortality benefit of AAA screening, at least in older men, is durable and cost-effective [38–42]. Prompted by these results, the federal government of the United States passed the screen for abdominal aortic aneurysms very efficiently (SAAAVE) Act in January 2007. Under this Act and as part of the “Welcome to Medicare” package, Medicare covers a one-time ultrasound screening of 65–75 year old men who ever smoked in their lifetime, and men/women who have a family history of AAA. In comparison, CT and MRI can produce vascular images at high resolution and are frequently used for accurate diagnosis and pre-operative evaluation. In the following section, we will briefly summarize these anatomical imaging techniques and their applications in AAA.

Fig. 1.

Representative anatomical images of AAA in patients and preclinical models, acquired with various imaging techniques. Top left: Contrast-enhanced ultrasound obtained 30 seconds after injection shows contrast extravasation (arrow) in ruptured AAA. Top right: Ultrasound images showing the aneurysm (A) and lumen (L) in a mouse. Scale bar: 0.5 mm. Center: Volume-rendered images of a patient from non-enhanced CT studies at stent placement and 1 year follow-up. Bottom: magnetic resonance angiogram (maximum-intensity projection) before (left) and after (right) endograft delivery in a swine model. Adapted from [47,55,64,75].

Ultrasound

Because of its safety, low cost, ease of use, and wide availability, ultrasonography is the most commonly used clinical imaging modality [43]. High-frequency sound waves are emitted from a transducer placed against the skin and ultrasound images are obtained based on the sound wave reflected back from the internal organs. The contrast of ultrasound is dependent on the sound speed, sound attenuation, backscatter, and the imaging algorithm [44].

Ultrasonography is the standard method for screening and monitoring AAAs that have not ruptured [45]. In the case of an emergency, bed-side ultrasound examination could act as an extension of routine ultrasound for specific symptoms. With the advance in 3-dimensional (3D) imaging, 3D ultrasonography has provided a new opportunity to acquire fast and reliable AAA measurements, which can not only shorten the time for a ultrasound exam but also reduce the workload of AAA surveillance [46]. Such 3D ultrasound imaging [47], as well as high frequency ultrasound [48], has also been used in preclinical models for AAA diagnosis. In addition, intravascular ultrasound is another tool that can be applied for endovascular management of AAA, such as confirming the AAA size measured in a routine abdominal CT scan [49].

Expansion of AAA, reflected by compliance, is related to the remodeling of the vascular matrix which may be an indicator of AAA behavior and thus useful for clinical detection. Tissue Doppler imaging (TDI) is a ultrasonographic technique which can allow wall motion measurement along an arterial segment with good reproducibility [50]. TDI has been applied to analyze AAA wall motion before and after EVAR [51]. Another technique, pulse-wave imaging (PWI), was reported to be capable of mapping the pulse-wave propagation along the abdominal aorta in living mice [52]. Since AAA leads to changes in the mechanical properties of the aortic wall, the pulse-wave velocity (PWV) may indicate a regional change due to the non-uniformity along the normal and pathological (e.g. AAA) arteries, which can be detected by PWI.

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) is another promising method for the diagnosis and follow-up of endoleaks after EVAR [53,54]. One study has reported that CEUS could reveal features specific for ruptured AAA without causing a significant delay in surgery [55]. Ultrasound surveillance after EVAR was safe, which could not only reduce the cost but also avoid the many complications associated with CT surveillance [56]. Overall, ultrasound has been widely used in the screening and diagnosis of AAA. However, the presence of bowel gas or obesity may limit its usefulness in many clinical scenarios. Further, ultrasound is not as accurate as CT angiography and cannot completely replace CT angiography in the follow-up of EVAR [57].

CT

CT is a medical imaging method where digital geometry processing is used to generate a 3D image of the internals of an object from a large series of 2D X-ray images taken around a single axis of rotation [58]. Contrast-enhanced CT has been widely used in the diagnosis of AAA [57,59]. The combination of speed, reproducibility, and spatial resolution makes CT a preferred method for more accurate follow-up of AAA, although the associated accumulated radiation dose is a concern.

EVAR requires precise measurement of the aortoiliac lengths and diameters to select the most suitable endograft. Contrast-enhanced spiral CT is the major tool for pre-operative evaluation and planning before treating AAA patients with stent graft [57,59,60]. Highly accurate aneurysm size and volume measurements can be achieved with this modality. Unlike open surgical repair, follow-up is vital for EVAR and regular post-operative imaging is typically needed for the life of the patient. Only long-term follow-up data will tell which method will become the standard for accurate detection of endoleak, aneurysm expansion, graft migration, and graft deformation, but physical examination, abdominal radiographs, and 3D spiral CT are the current clinical gold standard [61]. CT angiography can delineate endoleaks of AAA with a higher sensitivity over conventional angiography [62]. Further, pre-contrast CT images can also be helpful in differentiating calcification in the AAA sac from an endoleak [63].

To reduce the radiation exposure due to repeated CT scans, volumetric analysis of non-enhanced CT was evaluated as the sole method with which to follow up EVAR and to identify endoleaks [64]. It was found that serial volumetric analysis of AAA with non-enhanced CT could serve as an adequate screening test for endoleak, with significant reduction in radiation exposure. Another way to reduce the radiation exposure is to use ultrasonography instead of CT scans. In 1 study, comparison of CT and ultrasound revealed that CT-based measurement of AAA size tended to be larger than the ultrasound measurement [65]. In another report where a handheld ultrasound device and a newly developed ultrasound volume scanner was compared with CT for AAA diagnosis, both ultrasound devices were capable of effectively identifying the AAAs in patients that have been confirmed by CT [66].

MRI

MRI detects the interaction of protons (or certain other nuclei) with each other and with the surrounding molecules in a tissue [67]. Different tissues have different relaxation times that can result in endogenous MR contrast. Exogenous contrast agents can further enhance this by selectively shortening either the T1 (longitudinal) or T2 (transverse) relaxation time [68,69]. The MR image can be weighted to detect the differences in either T1 or T2 by adjusting certain parameters during data acquisition. Traditionally, Gd3+-chelates have been used to enhance the T1 contrast [70] and iron oxide nanoparticles have been used to increase the T2 contrast [71].

MRI can allow accurate anatomical delineation of AAA without the use of contrast agents or an intravascular catheter [72]. The use of MRI in the diagnosis of thrombus and evaluation of blood flow in aortic diseases has been demonstrated in patients with aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection about a decade ago [73]. Magnetic resonance angiography was reported to be at least as sensitive as CT angiography, and in some cases it could detect endoleaks that were not detected by CT angiography [74]. One study has also shown that real-time MRI guidance of EVAR in experimental swine AAA was feasible [75]. Further, MRI also permitted immediate post-procedural anatomic and functional evaluation of the success of AAA exclusion.

Conventional anatomical imaging of the vasculature using ultrasound, CT, MRI, and contrast-enhanced angiography gives valuable anatomical and morphological information about AAAs. Besides the advantages and disadvantages of each imaging modality as mentioned above, the cost of each imaging modality (e.g. purchase, maintenance, use of contrast agents, training of staff, etc.) also plays a role in the use of each technique. Another concern is that although contrast media provide significant diagnostic benefit, there is some risk of contrast medium-related adverse events in a small percentage of patients which may include renal failure [76], contrast-induced nephropathy [77], allergic reactions [78,79], among others. These considerations also apply to the radionuclide-based imaging techniques discussed later in this review. Each year, hundreds of thousands of new AAA cases are detected through screening programs and the majority of these new cases are small aneurysms, defined as < 5.5 cm in aortic diameter for men and < 5.0 cm for women, respectively. However, the benefit of early detection by screening is offset by the lack of effective medical treatment as well as reliable technologies to assess the true biological progression of AAA. Further, mounting clinical data indicated that AAA size is a poor marker for the prediction of AAA rupture [80]. Patients with similar aortic diameters may have experienced different environmental exposures and/or clinical courses, which can lead to substantially different underlying pathobiology. As a result, patients with identical AAA sizes often demonstrate significantly different morbidity, mortality, and responses to treatment. Clearly, simply measuring the AAA size accurately is not sufficient to improve AAA management and overall outcome.

FUNCTIONAL IMAGING OF AAA

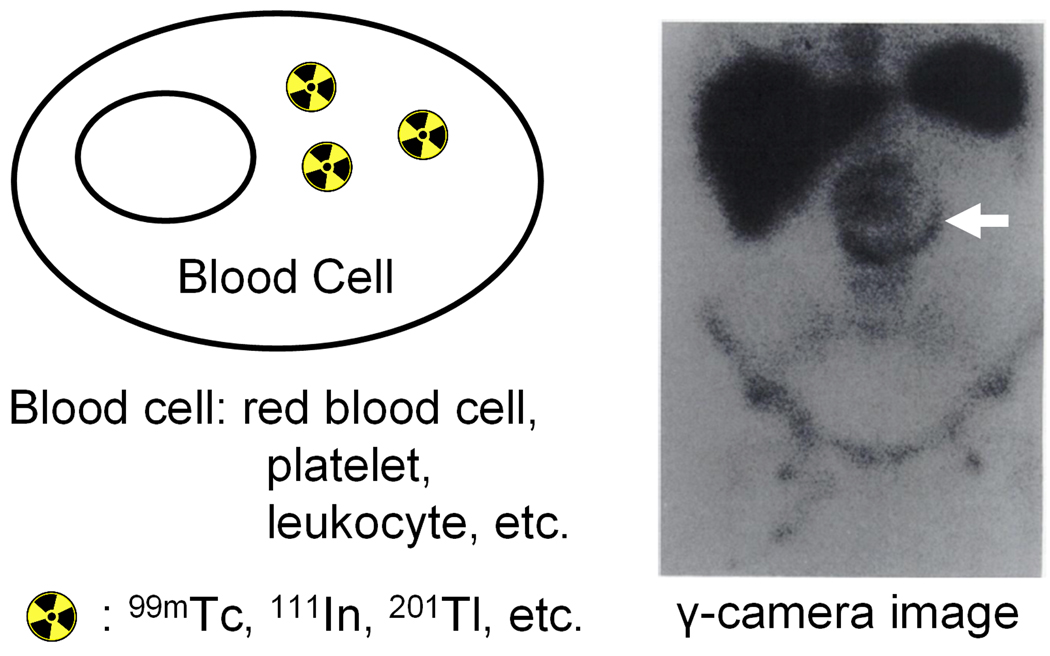

Functional imaging techniques can detect/measure changes in the metabolism, blood flow, regional chemical composition and absorption. As opposed to anatomical imaging, functional imaging reveals physiological activities within a certain tissue or organ by employing imaging techniques that often use tracers or probes, such as radiolabeled blood cells, to reflect their spatial distribution within the body. To date, functional imaging studies of AAA are almost exclusively with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT, Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Functional imaging of AAA. The cells can be labeled first and then intravenously injected or the tracer itself can be intravenously injected. A representative image after injection of radiolabeled red blood cells which delineates endoleak is shown. Adapted from [88].

SPECT imaging detects gamma rays [81]. Internal radiation is typically administered through injecting a low mass amount of radiolabeled pharmaceuticals. A collimator is used to only allow the emitted gamma photon to travel along certain directions to reach the detector, which ensures that the position on the detector accurately represents the source of the gamma ray. The gamma camera can be used in planar imaging to obtain 2D images, or in SPECT imaging to obtain 3D images. Common radioisotopes used for SPECT imaging are 99mTc (t1/2: 6.0 h), 111In (t1/2: 2.8 d), 123I (t1/2: 13.2 h), and 131I (t1/2: 8.0 d).

99mTc-labeled red blood cells (RBCs)

When properly labeled RBCs are injected into a patient, they can be fairly stable in the circulation thus allowing scintigraphic studies of the cardiovascular system. Radionuclide angiography with 99mTc-labeled RBCs was employed to detect AAAs more than 3 decades ago [82]. The technique was simple, non-invasive, and capable of functional evaluation by obtaining flow study. Recently, detection of endoleaks after EVAR with 99mTc-labeled sulfur colloid and 99mTc-labeled RBCs was reported [83]. Flow images were obtained, followed by sequential dynamic images, after intravenous administration of the agents. However, the sensitivity of these scintigraphic scanning methods for endoleak detection was significantly lower than that of CT angiography.

111In-labeled platelets

Labeling platelets with radionuclides offers several useful capabilities, such as the determination of their recovery and survival in the circulation. SPECT imaging with 111In-labeled platelets has been investigated in AAA patients. An early study of the survival and sites of sequestration of 111In-oxine-labeled autologous platelets in aneurysm patients suggested that although platelets were deposited in the aneurysm, many are damaged and are eventually sequestered in the reticuloendothelial system [84]. Subsequently, in a study where autologous platelet labeling was used to calculate the platelet half-life in patients with symptoms of coronary heart disease and/or peripheral arterial disease, abnormal deposition of 111In-labeled platelets indicated the presence of AAA in a small fraction of these patients [85]. Another case report also showed similar findings [86].

To quantitatively characterize the process of platelet thrombus formation in vivo, the kinetics and incorporation into thrombus of autologous 111In-labeled platelets were compared in patients with aortic aneurysms and prosthetic aortic grafts [87]. Although platelet survival was comparably shortened in both patient groups, the maximum radioactivity as determined by γ-camera imaging was significantly higher in the aneurysms than in the grafts. Compartmental analysis of the data indicated that the deposited platelet radioactivity had a longer residence time on grafts but accumulated at a faster rate in aneurysms, suggesting the presence of additional components of platelet destruction unrelated to graft and aneurysm thrombus formation. Besides platelets, 111In-labeled leukocytes have also been used for the imaging of an inflammatory AAA [88].

99mTc-sestamibi

99mTc-sestamibi (or 99mTc-MIBI), a lipophilic cation, has been mainly used for imaging the myocardium (heart muscle) [89]. When injected intravenously into a patient, it distributes in the myocardium proportionally to the myocardial blood flow. More than a decade ago, a prospective open study was carried out in patients (including a small portion of AAA patients) scheduled for elective vascular procedures to compare the ability of dobutamine (a sympathomimetic drug used in the treatment of heart failure and cardiogenic shock) stress echocardiography and dobutamine 99mTc-MIBI SPECT to predict post-operative cardiac events [90]. It was found that the cardiac response (ischemic versus non-ischemic) to dobutamine stress was concordantly classified by echocardiographic and SPECT techniques in 96% of cases.

Thallium-201

Thallium-201 (201Tl) has been used extensively as a myocardial perfusion agent and to assess myocardial viability [91,92]. Unlike 99mTc-MIBI, the regional concentration of 201Tl varies with time which makes it a good candidate for estimating absolute physiologic parameters with kinetic model analysis. One study compared the results of 201Tl myocardial SPECT of patients with arteriosclerosis obliterans (ASO), AAA, and Takayasu arteritis (TA) [93]. Qualitative analysis showed that myocardial perfusion was decreased most in patients with ASO, followed by patients with AAA, and was minimally decreased in patients with TA, suggesting that 201Tl myocardial SPECT should be performed in patients with ASO or AAA but not in TA patients. Subsequent studies also suggested that pre-operative 201Tl SPECT was useful for predicting peri-operative cardiac events in patients with vascular diseases (e.g. ASO and AAA), even in patients identified as having a low risk based on the clinical risk assessment [94,95].

Anatomical and functional imaging techniques, as described above, can reveal useful information in the diagnosis and management of AAA. However, these imaging techniques are insufficient to reveal the cellular/molecular event that may occur in the aortic wall long before any structural/functional changes become detectable. By the nature of the disease, acquisition of aortic tissue in small AAAs (the formative phase of the disease) is not a practical option. Therefore, our current knowledge of human AAAs originated primarily from histopathological analyses of aneurysmal wall specimens of patients who underwent rupture repair or elective surgical repair, both of which involve advanced or end stage AAAs. At this state, the arterial wall structure is grossly distorted which can only provide very limited insight into the events that have led to this aberrant tissue.

Because of the inability to study a developing AAA through biopsy or imaging, there is a severe paucity of information on the sequence of events that culminate in the initiation and growth of human AAAs. Therefore, we do not know precisely what triggers an aneurysm to rupture. Although in general the risk of rupture correlates with the AAA size, rupture has been reported in patients with small AAAs. There is a great need to develop new technologies that will enable us to study AAA development non-invasively in humans and to assess AAA progression and rupture risk more accurately. As part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has designated at least $200 million in fiscal years 2009 – 2010 for a new initiative called the NIH Challenge Grants in Health and Science Research. One of the challenge areas was to “develop technologies for assessment of aortic aneurysms prone to rupture or dissection”. Molecular imaging [96], a recently emerged field, can be a powerful tool in the diagnosis, patient management, and drug development for AAA.

MOLECULAR IMAGING

Molecular imaging, “the visualization, characterization and measurement of biological processes at the molecular and cellular levels in humans and other living systems” [97], has flourished over the last decade. In general, molecular imaging modalities include molecular MRI, magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), optical bioluminescence, optical fluorescence, targeted ultrasound, SPECT, and positron emission tomography (PET) [96]. Many hybrid imaging systems that combine 2 or more modalities are also commercially available and others are under active development [98–100].

Molecular imaging takes advantage of the traditional diagnostic imaging techniques and introduces molecular imaging agents (probes) to determine the expression of indicative molecular markers at different stages of diseases. It can give whole body readout in an intact system which is much more relevant and reliable than in vitro/ex vivo assays; help decrease the workload and speed up the drug development process; provide more statistically accurate results since longitudinal studies can be performed in the same animal which serves as its own control; aid in lesion detection in AAA patients and patient stratification; and help individualize treatment monitoring and dose optimization.

Molecular imaging is not only a promising approach for AAA evaluation but also a feasible one. Animal studies over the last decade have accumulated a wealth of information regarding the cellular and biochemical events underlying experimental AAA development. Such knowledge will serve as the basis for the initial design and testing of these molecular probes. The “holy grail” of AAA imaging is the ability to identify the AAAs that are prone to rupture using non-invasive molecular imaging techniques. Continued development and wider availability of scanners dedicated to small animal imaging studies, which can provide a similar in vivo imaging capability in mice, primates, and humans, can enable smooth transfer of knowledge and molecular measurements between species thereby facilitating clinical translation [101,102]. Non-invasive detection of the molecular markers of AAA can allow for much earlier diagnosis and treatment, as well as better prognosis that will eventually lead to personalized medicine. In the remainder of this review, we will summarize the current state-of-the-art of molecular imaging of AAA.

OPTICAL IMAGING OF AAA

The major limitation of optical imaging is the poor tissue penetration and intense scattering of light [103]. Imaging in the near-infrared (NIR, 700 – 900 nm) window, where the absorbance spectra for all biomolecules reach minima, can provide opportunities for rapid and cost-effective pre-clinical evaluation in small animal models before the more costly radionuclide-based imaging studies [104]. Neovascularization is a characteristic pathological feature of AAA and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) expression may mediate AAA growth and rupture. Recently, VEGFR expression as a function of AAA progression in a murine AAA model was investigated [105].

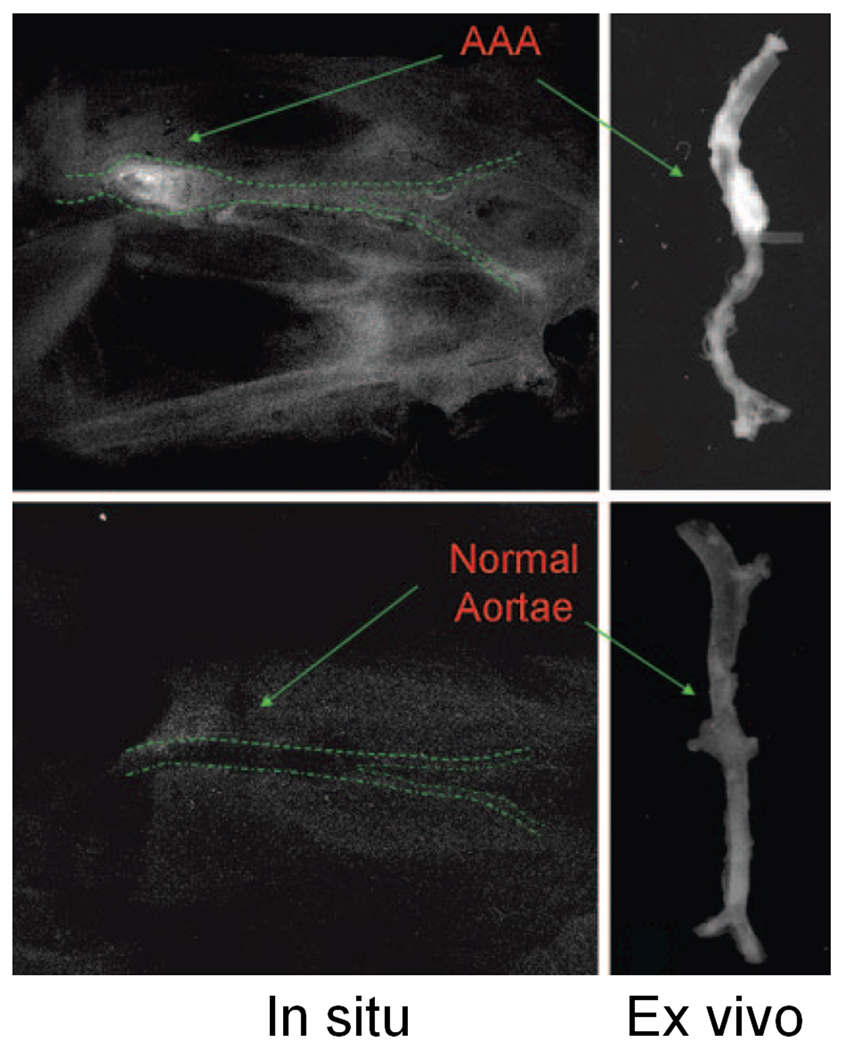

ApoE−/− mice maintained on a high-fat diet underwent continuous infusion with angiotensin II (Ang II) or vehicle (as a control) via subcutaneous osmotic pump [105]. NIR fluorescence imaging was performed with scVEGF/Cy, a single-chain VEGF homo-dimer labeled with Cy5.5. Another AAA mouse cohort received either an oral angiogenesis inhibitor or suitable negative or positive controls to further validate the significance of angiogenesis in experimental AAA progression. Significantly greater fluorescence signal of scVEGF/Cy was obtained from aneurysmal aorta than the various controls (Figure 3). Further, the signal intensity increased in a diameter-dependent fashion in aneurysmal segments and treatment with an angiogenesis inhibitor attenuated AAA formation.

Fig. 3.

Optical imaging of VEGFR expression in AAA with scVEGF/Cy. Both in situ images after abdominal evisceration and bilateral nephrectomies and ex vivo images of the aorta are shown. Adapted from [105].

This study demonstrated the feasibility of imaging VEGFR expression in experimental AAAs as a surrogate for disease progression, which warrants further investigation into the potential significance of VEGF and VEGFR activity in AAA pathogenesis. For clinical applications, optical imaging will only be possible in limited sites such as the tissues and lesions close to the surface of the skin, tissues accessible by endoscopy and intraoperative visualization. NIR optical imaging devices for detecting and diagnosing breast cancer have been tested in patients and the initial results are encouraging [106,107]. Clinical VEGFR expression imaging strategies, if feasible, may improve real-time monitoring of AAA disease progression and response to therapeutic intervention.

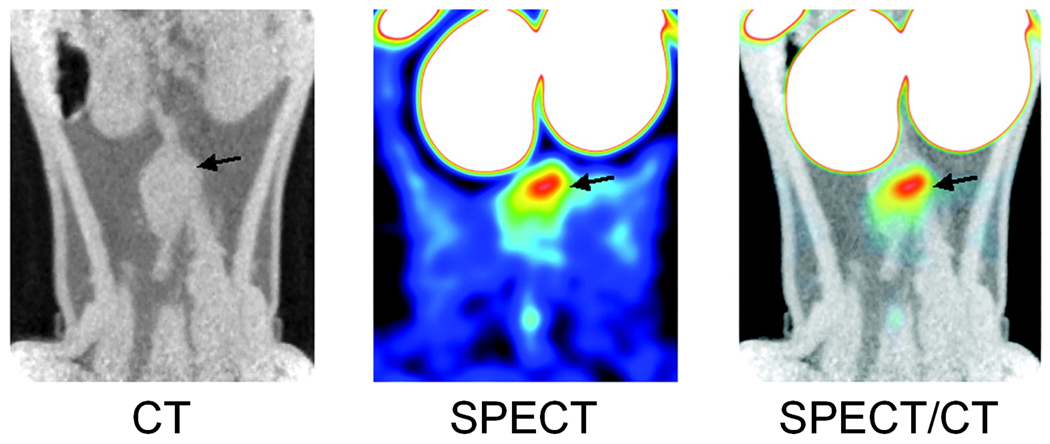

SPECT IMAGING OF AAA

99mTc-annexin V is a tracer that binds to phosphatidylserine exposed on activated platelets and apoptotic cells [108]. In one study, the potential of 99mTc-annexin V imaging to assess mural thrombus biological activity in an experimental AAA model was investigated [109]. Most of the rats with AAA exhibited intense 99mTc-annexin V uptake within AAA by scintigraphy, significantly higher than that of the sham-operated controls (Figure 4). This activity was located in the thrombus area where activated platelets and polymorphonuclear leukocytes accumulated. More importantly, the clinical applicability of this tracer was tested on human samples of excised AAA thrombi and similar patterns were found in all of the human samples.

Fig. 4.

Frontal views of infrarenal aortic aneurysm in a rat as visualized by SPECT/CT imaging after injection of 99mTc-annexin V. Arrow indicates the upper part of the aneurysm. Adapted from [109].

Because of the use of lead collimators to define the angle of incidence, SPECT imaging has a very low detection efficiency (< 10−4 times the emitted number of gamma rays) [110]. One advantage of SPECT is that it can potentially allow simultaneous detection of multiple biological events with multiple isotopes (the gamma ray emitted from different radioisotopes can be differentiated based on the energy), as reported in some functional imaging studies [111]. However, whether dual-isotope SPECT imaging of the molecular signatures of AAA is feasible remains to be demonstrated. PET has higher sensitivity than SPECT [112]. With the continuous developmental effort, state-of-the-art small animal PET scanners can have spatial resolution (< 1 mm) comparable to SPECT and they are also becoming increasingly widely available [110,113].

PET IMAGING OF AAA

PET, a nuclear medicine imaging technique which produces a 3D image or map of functional processes in the body, was first developed in the mid 1970s [114]. The most widely used PET isotopes include 11C (t1/2: 20 min) and 18F (t1/2: 110 min). PET has extremely high sensitivity (down to the picomolar level) and it is highly quantitative. It has been widely used in the clinic for decades [112,115] and small animal PET scanners have also become widely available over the last 10 years. Therefore, the development of novel PET probes for AAA imaging has excellent translational potential, eventually benefiting AAA patients within a short time scale.

To date, PET imaging of AAA has been exclusively studied with 18F-fluoro-deoxy-glucose (18F-FDG), a clinical “gold standard” for cancer diagnosis, staging and treatment monitoring [116]. One disadvantage of 18F-FDG is its uptake in inflammatory tissues which can cause false-positives in cancer imaging [117]. However, this feature can be quite useful in AAA imaging and studies have shown that increased 18F-FDG uptake in AAAs is associated with inflammation, aortic wall instability and acute symptoms.

One early study investigated the increased metabolic activity in AAA by 18F-FDG PET and suggested a possible association between increased 18F-FDG uptake and AAA expansion and rupture [118]. A follow-up study further indicated that 18F-FDG uptake in the AAA wall may correspond to the accumulation of inflammatory cells responsible for the production and activation of degrading enzymes [119]. Based on these findings, positive 18F-FDG PET could help clinicians to decide to proceed with repair, despite the other factors favoring surveillance.

Subsequently, many interesting case reports appeared in the literature. In one report, an aortoenteric fistula was diagnosed by 18F-FDG PET which led to rapid surgical intervention with graft removal and extraanatomic bypass [120]. In another report, PET imaging combined with immunohistologic examination showed a region of increased 18F-FDG uptake which corresponded to an inflammatory infiltrate in the aortic wall in contrast to the thrombus in the aneurysm (devoid of inflammatory cells), while the luminal area showed medium 18F-FDG uptake which corresponded to circulating mediators [121]. One comprehensive imaging study confirmed the diagnosis of an infected AAA by several different imaging modalities including CT, MRI, 111In-labeled white blood cell SPECT, and 18F-FDG PET [122]. Concordance among these modalities demonstrated that 18F-FDG PET can be a useful component of the mycotic aneurysm diagnostic armamentarium. In other reports, diagnosis/identification of epithelioid angiosarcoma in the vessel wall of an AAA [123], infected AAA due to Salmonella enteritidis [124], occult infectious foci in Coxiella burnetii-infected vascular grafts [125], have been described. These encouraging results warrant larger controlled studies to evaluate the utility of 18F-FDG PET in the diagnosis of various AAA-related clinical scenarios.

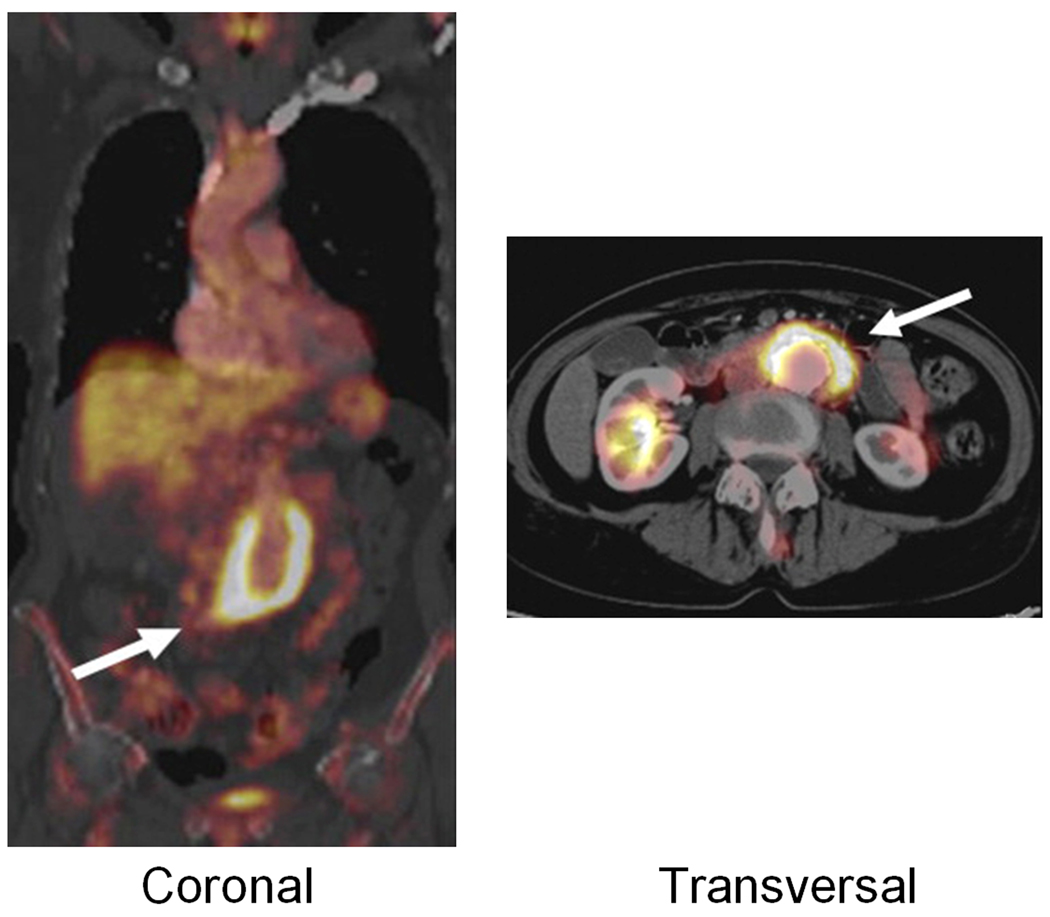

Following these early studies and case reports, several studies have focused on the use of 18F-FDG PET in AAA diagnosis and management [126]. One study showed that symptomatic AAAs had significantly increased 18F-FDG uptake compared with asymptomatic AAAs (Figure 5), which was correlated with higher densities of inflammatory infiltrates, higher MMP-9 expressions, and with reduction of collagen fiber and vascular SMCs [127]. Another study reported that AAAs had significantly higher 18F-FDG uptake than the normal-sized aorta in age-matched controls [128]. More importantly, irrespective of the AAA diameter, asymptomatic AAAs showed more 18F-FDG uptake and more inflammatory activity in the wall than the non-dilated abdominal aorta of sex/age-matched controls.

Fig. 5.

18F-FDG PET/CT of an AAA vessel wall (arrows) in a patient. Adapted from [127].

These findings clearly indicated that 18F-FDG PET can be a new diagnostic technique to study AAA in vivo and may help in the prediction of the rupture risk. Future studies should be directed at the predictive value of increased 18F-FDG uptake for aneurysm wall strength, rupture risk, and the utility of 18F-FDG PET in assessing the effect of medical interventions. Recently, pre-operative 18F-FDG PET/CT performed in patients considered fit for aneurysm repair identified concomitant malignancy in a significant portion of the patients [129], indicating a big impact on AAA patient management as a result of the sensitivity of 18F-FDG PET/CT for detecting malignancy.

Despite the encouraging results described above, a few reports indicated caution in 18F-FDG PET of AAA-related situations. For example, one study aimed at assessing 18F-FDG uptake in vascular grafts in patients with or without symptoms of graft infection revealed that 18F-FDG uptake in vascular grafts was present in the vast majority of patients without graft infection [130]. Therefore, the risk of a false-positive diagnosis of graft infection by 18F-FDG PET/CT is evident. In another report which was focused on detecting increased metabolic activity in the aneurysm wall with 18F-FDG PET, there was no significant difference in 18F-FDG uptake between heavily calcified aneurysms and non-heavily calcified aneurysms [131].

SUMMARY AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

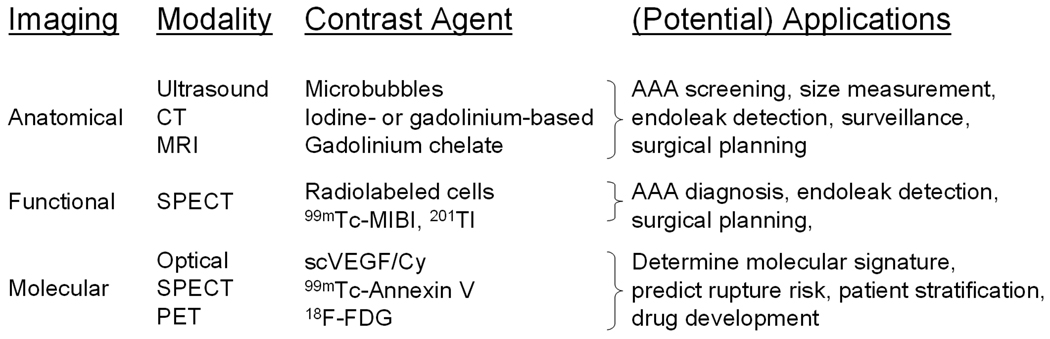

A variety of imaging techniques have been explored for various applications in AAA diagnosis and management (Figure 6). Anatomical imaging of AAA has been widely used over the last decade, both clinically and preclinically. The techniques associated with ultrasound, CT and MRI have become mature and standardized. Functional imaging of AAA, on the other hand, has not been well documented in the literature. Over the last several years, molecular imaging of AAA has gained significant momentum and we expect many more studies to emerge over the forthcoming years. Non-invasive molecular imaging of AAA has clinical applications in many aspects, with the most important ones being patient stratification (i.e. identifying those AAAs that are prone to rupture). The future of AAA imaging lies in the combination of anatomical and molecular imaging techniques, which are largely complementary rather than competitive. There are many challenges, as well as many areas that deserve extensive investigation, in molecular imaging of AAA in the future.

Fig. 6.

A brief summary of various imaging techniques for AAA diagnosis and management.

First, although studies using preclinical models are the indispensable initial steps toward future clinical studies, whether the animal AAA models truly represent the clinical situation is debatable. Several rodent models have been developed and widely used in aneurysm research. Application of exogenous chemicals (elastase, Ang II, or calcium chloride) directly or indirectly to the aortic walls can produce an aortic dilation in animals (mostly mice) that mimics the pathophysiological features of human AAA, such as vascular inflammation, degradation of ECM, depletion of arterial SMCs, neovascularization, and elevated level of cytokines and matrix-degrading enzymes (MMPs in particular) [5]. However, without enough knowledge of aneurysm development in humans, it is difficult to determine whether the cellular and biochemical mechanisms derived from animal models are applicable to AAA patients.

Second, the ideal imaging targets for molecular imaging of AAA need to be identified and validated. Although the molecular mechanism underlying AAA growth or rupture remains inconclusive, several biological events including angiogenesis, apoptosis, inflammation, and proteolysis (in particular the loss of collagen) have been implicated [132]. Since AAAs often co-exist with other chronic conditions such as atherosclerosis and hypertension, the specific molecular markers for AAA severity/rupture risk are likely to reside within the abdominal aortic wall which is suitable for imaging applications. The complete sequencing of the human genome has ushered in a new era of systems biology referred to as “-omics” [133] and genomic/proteomic molecular profiling technologies are transforming biomedical research [134,135]. These constantly evolving technologies may lead to the discovery of new biomarkers for AAA rupture risk. Among hundreds of genes that were found to be differentially expressed in the rupture edge as compared to the anterior sac of AAA tissues, many of them encode factors that are involved in angiogenesis, inflammation and apoptosis [136]. Some of these features/pathways have been extensively studied in other diseases such as atherosclerosis and cancer [137–141]. Therefore, many of the already existing molecular imaging probes may be directly applicable for AAA imaging.

Third, application of nanoparticles in AAA-relate research is a virtually unexplored field to date. Nanotechnology, an interdisciplinary research field involving physics, chemistry, engineering, biology, and medicine, has great potential for early detection, accurate diagnosis, and personalized treatment of diseases [142,143]. With the size of many orders of magnitude smaller than human cells, nanoparticles can offer unprecedented interactions with biomolecules both on the surface of and inside the cells, which may revolutionize disease diagnosis and treatment. One of the most promising clinical applications of nanoparticle-based agents will be in cardiovascular diseases, such as AAA, where there is much less biological barrier for efficient delivery of nanoparticles.

Fourth, with the development of new tracers with better targeting efficacy and desirable pharmacokinetics, clinical translation of the imaging probes will be critical for the maximum benefit of AAA patients. Radionuclide-based imaging (SPECT and PET) has much more clinical relevance than molecular MRI, targeted ultrasound, and optical imaging. However, most of the very promising results on novel PET/SPECT tracers in small animal disease models never moved a step further into the clinical setting due to many obstacles such as the federal/institutional regulations, disconnection between the scientists and clinicians, the daunting cost of clinical translation, among many others. To foster the continued discovery and development of AAA imaging agents, cooperative efforts are needed from cellular/molecular biologists to identify and validate novel imaging targets as well as more clinically relevant animal models and chemists/radiochemists to synthesize and characterize the imaging probes. Close partnerships among academic researchers, clinicians (in particular vascular surgeons), the pharmaceutical industry (many of the leading companies already have an interest in molecular imaging), the National Institutes of Health, and the Food and Drug Administration are needed to quickly apply molecular imaging to multiple facets of AAA patient management. Ultimately, with the right molecular imaging probe, clinicians will be able to monitor AAA growth and evaluate the risk of rupture accurately, so that the life-saving intervention can be provided to the right patients at the right time. Equally important, the right imaging probe will also allow scientists/clinicians to acquire critical data during AAA development in humans and to more accurately evaluate the efficacy of potential new treatments in clinical trials.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge financial support from the UW School of Medicine and Public Health’s Medical Education and Research Committee through the Wisconsin Partnership Program, the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center, NCRR 1UL1RR025011, NHBLI R01 HL-81424, an American Heart Association grant-in-aid 0455859T, and a Susan G. Komen Postdoctoral Fellowship (to H. Hong).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belsley SJ, Tilson MD. Two decades of research on etiology and genetic factors in the abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)--with a glimpse into the 21st century. Acta Chir Belg. 2003;103:187–196. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2003.11679405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parodi JC, Palmaz JC, Barone HD. Transfemoral intraluminal graft implantation for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg. 1991;5:491–499. doi: 10.1007/BF02015271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prinssen M, Verhoeven EL, Buth J, et al. A randomized trial comparing conventional and endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1607–1618. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daugherty A, Cassis LA. Mouse models of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:429–434. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000118013.72016.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMillan WD, Patterson BK, Keen RR, Pearce WH. In situ localization and quantification of seventy-two-kilodalton type IV collagenase in aneurysmal, occlusive, and normal aorta. J Vasc Surg. 1995;22:295–305. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(95)70144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higashikata T, Yamagishi M, Sasaki H, et al. Application of real-time RT-PCR to quantifying gene expression of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in human abdominal aortic aneurysm. Atherosclerosis. 2004;177:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrell TW, Burnand KG, Wells GM, Clements JM, Smith A. Stromelysin-1 (matrix metalloproteinase-3) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3 are overexpressed in the wall of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circulation. 2002;105:477–482. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fontaine V, Jacob MP, Houard X, et al. Involvement of the mural thrombus as a site of protease release and activation in human aortic aneurysms. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1701–1710. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64447-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMillan WD, Patterson BK, Keen RR, et al. In situ localization and quantification of mRNA for 92-kD type IV collagenase and its inhibitor in aneurysmal, occlusive, and normal aorta. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:1139–1144. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.8.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hovsepian DM, Ziporin SJ, Sakurai MK, et al. Elevated plasma levels of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms: a circulating marker of degenerative aneurysm disease. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:1345–1352. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elmore JR, Keister BF, Franklin DP, Youkey JR, Carey DJ. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases and TIMPs in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg. 1998;12:221–228. doi: 10.1007/s100169900144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Annabi B, Shedid D, Ghosn P, et al. Differential regulation of matrix metalloproteinase activities in abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:539–546. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.121124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curci JA, Liao S, Huffman MD, Shapiro SD, Thompson RW. Expression and localization of macrophage elastase (matrix metalloproteinase-12) in abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1900–1910. doi: 10.1172/JCI2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pyo R, Lee JK, Shipley JM, et al. Targeted gene disruption of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (gelatinase B) suppresses development of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1641–1649. doi: 10.1172/JCI8931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longo GM, Xiong W, Greiner TC, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 work in concert to produce aortic aneurysms. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:625–632. doi: 10.1172/JCI15334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosorin M, Juvonen J, Biancari F, et al. Use of doxycycline to decrease the growth rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:606–610. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.117891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baxter BT, Pearce WH, Waltke EA, et al. Prolonged administration of doxycycline in patients with small asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysms: report of a prospective (Phase II) multicenter study. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:1–12. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.125018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paraskevas KI, Liapis CD, Hamilton G, Mikhailidis DP. Are statins an option in the management of abdominal aortic aneurysms? Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2008;42:128–134. doi: 10.1177/1538574407308205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stalenhoef AF. The benefit of statins in non-cardiac vascular surgery patients. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ailawadi G, Eliason JL, Upchurch GR., Jr Current concepts in the pathogenesis of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:584–588. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eliason JL, Hannawa KK, Ailawadi G, et al. Neutrophil depletion inhibits experimental abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Circulation. 2005;112:232–240. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.517391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong W, Zhao Y, Prall A, Greiner TC, Baxter BT. Key roles of CD4+ T cells and IFN-gamma in the development of abdominal aortic aneurysms in a murine model. J Immunol. 2004;172:2607–2612. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun J, Sukhova GK, Yang M, et al. Mast cells modulate the pathogenesis of elastase-induced abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3359–3368. doi: 10.1172/JCI31311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimizu K, Shichiri M, Libby P, Lee RT, Mitchell RN. Th2-predominant inflammation and blockade of IFN-gamma signaling induce aneurysms in allografted aortas. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:300–308. doi: 10.1172/JCI19855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wassef M, Upchurch GR, Jr, Kuivaniemi H, Thompson RW, Tilson MD. 3rd Challenges and opportunities in abdominal aortic aneurysm research. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coll B, Alonso-Villaverde C, Joven J. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and atherosclerosis: is there room for an additional biomarker? Clin Chim Acta. 2007;383:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dawson J, Miltz W, Mir AK, Wiessner C. Targeting monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 signalling in disease. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2003;7:35–48. doi: 10.1517/14728222.7.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schubl S, Tsai S, Ryer EJ, et al. Upregulation of protein kinase cdelta in vascular smooth muscle cells promotes inflammation in abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Surg Res. 2009;153:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishibashi M, Egashira K, Zhao Q, et al. Bone marrow-derived monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 receptor CCR2 is critical in angiotensin II-induced acceleration of atherosclerosis and aneurysm formation in hypercholesterolemic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:e174–e178. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000143384.69170.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ni W, Kitamoto S, Ishibashi M, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 is an essential inflammatory mediator in angiotensin II-induced progression of established atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:534–539. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000118275.60121.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopez-Candales A, Holmes DR, Liao S, et al. Decreased vascular smooth muscle cell density in medial degeneration of human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:993–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henderson EL, Geng YJ, Sukhova GK, et al. Death of smooth muscle cells and expression of mediators of apoptosis by T lymphocytes in human abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circulation. 1999;99:96–104. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walton LJ, Franklin IJ, Bayston T, et al. Inhibition of prostaglandin E2 synthesis in abdominal aortic aneurysms: implications for smooth muscle cell viability, inflammatory processes, and the expansion of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circulation. 1999;100:48–54. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sinha I, Sinha-Hikim AP, Hannawa KK, et al. Mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis in experimental rodent abdominal aortic aneurysms. Surgery. 2005;138:806–811. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson RW, Liao S, Curci JA. Vascular smooth muscle cell apoptosis in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Coron Artery Dis. 1997;8:623–631. doi: 10.1097/00019501-199710000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Curci JA. Digging in the "soil" of the aorta to understand the growth of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Vascular. 2009;1(17 Suppl):S21–S29. doi: 10.2310/6670.2008.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ashton HA, Buxton MJ, Day NE, et al. The Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS) into the effect of abdominal aortic aneurysm screening on mortality in men: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1531–1539. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11522-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scott RA, Bridgewater SG, Ashton HA. Randomized clinical trial of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm in women. Br J Surg. 2002;89:283–285. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.02014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson SG, Ashton HA, Gao L, Scott RA. Screening men for abdominal aortic aneurysm: 10 year mortality and cost effectiveness results from the randomised Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study. BMJ. 2009;338:b2307. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Multicentre aneurysm screening study (MASS): cost effectiveness analysis of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms based on four year results from randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;325:1135. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7373.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norman PE, Jamrozik K, Lawrence-Brown MM, et al. Population based randomised controlled trial on impact of screening on mortality from abdominal aortic aneurysm. BMJ. 2004;329:1259. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38272.478438.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bloch SH, Dayton PA, Ferrara KW. Targeted imaging using ultrasound contrast agents. Progess and opportunities for clinical and research applications. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2004;23:18–29. doi: 10.1109/memb.2004.1360405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wink MH, Wijkstra H, De La Rosette JJ, Grimbergen CA. Ultrasound imaging and contrast agents: a safe alternative to MRI? Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2006;15:93–100. doi: 10.1080/13645700600674252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roshanali F, Mandegar MH, Yousefnia MA, Mohammadi A, Baharvand B. Abdominal aorta screening during transthoracic echocardiography. Echocardiography. 2007;24:685–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2007.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nyhsen CM, Elliott ST. Rapid assessment of abdominal aortic aneurysms by 3-dimensional ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:223–226. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldberg A, Pakkiri P, Dai E, Lucas A, Fenster A. Measurements of aneurysm morphology determined by 3-d micro-ultrasound imaging as potential quantitative biomarkers in a mouse aneurysm model. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2007;33:1552–1560. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin-McNulty B, Vincelette J, Vergona R, Sullivan ME, Wang YX. Noninvasive measurement of abdominal aortic aneurysms in intact mice by a high-frequency ultrasound imaging system. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2005;31:745–749. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kpodonu J, Ramaiah VG, Diethrich EB. Intravascular ultrasound imaging as applied to the aorta: a new tool for the cardiovascular surgeon. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:1391–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Long A, Rouet L, Bissery A, et al. Compliance of abdominal aortic aneurysms: evaluation of tissue Doppler imaging. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2004;30:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Long A, Rouet L, Vitry F, et al. Compliance of abdominal aortic aneurysms before and after stenting with tissue doppler imaging: evolution during follow-up and correlation with aneurysm diameter. Ann Vasc Surg. 2009;23:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luo J, Fujikura K, Tyrie LS, Tilson MD, Konofagou EE. Pulse wave imaging of normal and aneurysmal abdominal aortas in vivo. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2009;28:477–486. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2008.928179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clevert DA, Minaifar N, Kopp R, et al. Imaging of endoleaks after endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) with contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS). A pictorial comparison with CTA. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2009;41:151–168. doi: 10.3233/CH-2009-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun Z. Diagnostic value of color duplex ultrasonography in the follow-up of endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:759–764. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000217944.36738.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Catalano O, Lobianco R, Cusati B, Siani A. Contrast-enhanced sonography for diagnosis of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:423–427. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.2.01840423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chaer RA, Gushchin A, Rhee R, et al. Duplex ultrasound as the sole long-term surveillance method post-endovascular aneurysm repair: a safe alternative for stable aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:845–849. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.10.073. discussion 9–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nyman R, Eriksson MO. The future of imaging in the management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Scand J Surg. 2008;97:110–115. doi: 10.1177/145749690809700206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mortele KJ, McTavish J, Ros PR. Current techniques of computed tomography. Helical CT, multidetector CT, and 3D reconstruction. Clin Liver Dis. 2002;6:29–52. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(03)00065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stavropoulos SW, Charagundla SR. Imaging techniques for detection and management of endoleaks after endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. Radiology. 2007;243:641–655. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2433051649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Broeders IA, Blankensteijn JD. Preoperative imaging of the aortoiliac anatomy in endovascular aneurysm surgery. Semin Vasc Surg. 1999;12:306–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fillinger MF. Postoperative imaging after endovascular AAA repair. Semin Vasc Surg. 1999;12:327–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Armerding MD, Rubin GD, Beaulieu CF, et al. Aortic aneurysmal disease: assessment of stent-graft treatment-CT versus conventional angiography. Radiology. 2000;215:138–146. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.1.r00ap28138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rozenblit AM, Patlas M, Rosenbaum AT, et al. Detection of endoleaks after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm: value of unenhanced and delayed helical CT acquisitions. Radiology. 2003;227:426–433. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2272020555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bley TA, Chase PJ, Reeder SB, et al. Endovascular Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair: Nonenhanced Volumetric CT for Follow-up. Radiology. 2009 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2531082093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Manning BJ, Kristmundsson T, Sonesson B, Resch T. Abdominal aortic aneurysm diameter: a comparison of ultrasound measurements with those from standard and three-dimensional computed tomography reconstruction. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.02.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vidakovic R, Feringa HH, Kuiper RJ, et al. Comparison with computed tomography of two ultrasound devices for diagnosis of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:1786–1791. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pathak AP, Gimi B, Glunde K, et al. Molecular and functional imaging of cancer: Advances in MRI and MRS. Methods Enzymol. 2004;386:3–60. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)86001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Z, Nair SA, McMurry TJ. Gadolinium meets medicinal chemistry: MRI contrast agent development. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:751–778. doi: 10.2174/0929867053507379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pautler RG, Fraser SE. The year(s) of the contrast agent - micro-MRI in the new millennium. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:385–392. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Roos A, Doornbos J, Baleriaux D, Bloem HL, Falke TH. Clinical applications of gadolinium-DTPA in MRI. Magn Reson Annu. 1988:113–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thorek DL, Chen AK, Czupryna J, Tsourkas A. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle probes for molecular imaging. Ann Biomed Eng. 2006;34:23–38. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-9002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sardelic F, Fletcher JP, Ho D, Simmons K. Assessment of abdominal aortic aneurysm with magnetic resonance imaging. Australas Radiol. 1995;39:107–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.1995.tb00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Honda T, Hamada M, Matsumoto Y, Matsuoka H, Hiwada K. Diagnosis of Thrombus and Blood Flow in Aortic Aneurysm Using Tagging Cine Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Int J Angiol. 1999;8:57–61. doi: 10.1007/BF01616845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wicky S, Fan CM, Geller SC, et al. MR angiography of endoleak with inconclusive concomitant CT angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:736–738. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.3.1810736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Raman VK, Karmarkar PV, Guttman MA, et al. Real-time magnetic resonance-guided endovascular repair of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysm in swine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:2069–2077. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schrader R. Contrast material-induced renal failure: an overview. J Interv Cardiol. 2005;18:417–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2005.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stacul F. Reducing the risks for contrast-induced nephropathy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2005;2(28 Suppl):S12–S18. doi: 10.1007/s00270-005-0197-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brockow K. Contrast media hypersensitivity--scope of the problem. Toxicology. 2005;209:189–192. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Idee JM, Pines E, Prigent P, Corot C. Allergy-like reactions to iodinated contrast agents. A critical analysis. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2005;19:263–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2005.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Golledge J, Tsao PS, Dalman RL, Norman PE. Circulating markers of abdominal aortic aneurysm presence and progression. Circulation. 2008;118:2382–2392. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.802074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Peremans K, Cornelissen B, Van Den Bossche B, Audenaert K, Van de Wiele C. A review of small animal imaging planar and pinhole spect Gamma camera imaging. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2005;46:162–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2005.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ryo UY, Pinsky SM. Radionuclide angiography with 99m technetium-RBCs. CRC Crit Rev Clin Radiol Nucl Med. 1976;8:107–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Stavropoulos SW, Itkin M, Lakhani P, et al. Detection of endoleaks after endovascular aneurysm repair with use of technetium-99m sulfur colloid and 99mTc-labeled red blood cell scans. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:1739–1743. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000241892.81074.1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Heyns AD, Lotter MG, Badenhorst PN, et al. Kinetics and fate of indium 111 oxine-labeled platelets in patients with aortic aneurysms. Arch Surg. 1982;117:1170–1174. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1982.01380330032009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sinzinger H, O'Grady J, Fitscha P, Silberbauer K, Hofer R. Detection of aneurysms by gamma-camera imaging after injection of autologous labelled platelets. Lancet. 1984;2:1365–1367. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Forstrom L, Thorpe P, Weir EK, Johnson T. Detection of an abdominal aneurysm by indium-111 platelet imaging. Clin Nucl Med. 1985;10:683–685. doi: 10.1097/00003072-198510000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hanson SR, Kotze HF, Pieters H, Heyns AD. Analysis of indium-111 platelet kinetics and imaging in patients with aortic grafts and abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arteriosclerosis. 1990;10:1037–1044. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.10.6.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bourekas EC, Tupler RH, Turbiner EH. Indium-111 imaging of an inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:1553–1555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mandalapu BP, Amato M, Stratmann HG. Technetium Tc 99m sestamibi myocardial perfusion imaging: current role for evaluation of prognosis. Chest. 1999;115:1684–1694. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.6.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Van Damme H, Pierard L, Gillain D, et al. Cardiac risk assessment before vascular surgery: a prospective study comparing clinical evaluation, dobutamine stress echocardiography, and dobutamine Tc-99m sestamibi tomoscintigraphy. Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;5:54–64. doi: 10.1016/s0967-2109(96)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Iida H, Eberl S. Quantitative assessment of regional myocardial blood flow with thallium-201 and SPECT. J Nucl Cardiol. 1998;5:313–331. doi: 10.1016/s1071-3581(98)90133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Verani MS. Thallium-201 single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) in the assessment of coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70 doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90032-t. 3E–9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Murata Y, Yamada I, Umehara I, Shibuya H. Tl-201 myocardial SPECT in patients with systemic arterial diseases. Clin Nucl Med. 1998;23:832–835. doi: 10.1097/00003072-199812000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chen T, Kuwabara Y, Tsutsui H, et al. The usefulness of dipyridamole thallium-201 single photon emission computed tomography for predicting perioperative cardiac events in patients undergoing non-cardiac vascular surgery. Ann Nucl Med. 2002;16:45–53. doi: 10.1007/BF02995291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Harafuji K, Chikamori T, Kawaguchi S, et al. Value of pharmacologic stress myocardial perfusion imaging for preoperative risk stratification for aortic surgery. Circ J. 2005;69:558–563. doi: 10.1253/circj.69.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Massoud TF, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging in living subjects: seeing fundamental biological processes in a new light. Genes Dev. 2003;17:545–580. doi: 10.1101/gad.1047403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mankoff DA. A definition of molecular imaging. J Nucl Med. 2007;48 18N, 21N. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Beyer T, Townsend DW, Brun T, et al. A combined PET/CT scanner for clinical oncology. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1369–1379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Even-Sapir E, Lerman H, Lievshitz G, et al. Lymphoscintigraphy for sentinel node mapping using a hybrid SPECT/CT system. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1413–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Catana C, Wu Y, Judenhofer MS, et al. Simultaneous acquisition of multislice PET and MR images: initial results with a MR-compatible PET scanner. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1968–1976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Koo V, Hamilton PW, Williamson K. Non-invasive in vivo imaging in small animal research. Cell Oncol. 2006;28:127–139. doi: 10.1155/2006/245619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pomper MG, Lee JS. Small animal imaging in drug development. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:3247–3272. doi: 10.2174/138161205774424681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cheong WF, Prahl SA, Welch AJ. A review of the optical properties of biological tissues. IEEE J. 1990;26:2166–2185. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Frangioni JV. In vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:626–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tedesco MM, Terashima M, Blankenberg FG, et al. Analysis of In Situ and Ex Vivo Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor Expression During Experimental Aortic Aneurysm Progression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.187757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Taroni P, Danesini G, Torricelli A, et al. Clinical trial of time-resolved scanning optical mammography at 4 wavelengths between 683 and 975 nm. J Biomed Opt. 2004;9:464–473. doi: 10.1117/1.1695561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Intes X. Time-domain optical mammography SoftScan: initial results. Acad Radiol. 2005;12:934–947. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Boersma HH, Kietselaer BL, Stolk LM, et al. Past, present, and future of annexin A5: from protein discovery to clinical applications. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:2035–2050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sarda-Mantel L, Coutard M, Rouzet F, et al. 99mTc-annexin-V functional imaging of luminal thrombus activity in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2153–2159. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000237605.25666.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chatziioannou AF. Instrumentation for molecular imaging in preclinical research: Micro-PET and Micro-SPECT. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:533–536. doi: 10.1513/pats.200508-079DS. 10–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Berman DS, Kiat H, Van Train K, et al. Dual-isotope myocardial perfusion SPECT with rest thallium-201 and stress Tc-99m sestamibi. Cardiol Clin. 1994;12:261–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging of cancer with positron emission tomography. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:683–693. doi: 10.1038/nrc882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Stickel JR, Qi J, Cherry SR. Fabrication and characterization of a 0.5-mm lutetium oxyorthosilicate detector array for high-resolution PET applications. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Phelps ME, Hoffman EJ, Mullani NA, Ter-Pogossian MM. Application of annihilation coincidence detection to transaxial reconstruction tomography. J Nucl Med. 1975;16:210–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Phelps ME. PET: the merging of biology and imaging into molecular imaging. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:661–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gambhir SS, Czernin J, Schwimmer J, et al. A tabulated summary of the FDG PET literature. J Nucl Med. 2001;42 1S–93S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rosenbaum SJ, Lind T, Antoch G, Bockisch A. False-positive FDG PET uptake--the role of PET/CT. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1054–1065. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-0088-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sakalihasan N, Van Damme H, Gomez P, et al. Positron emission tomography (PET) evaluation of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;23:431–436. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sakalihasan N, Hustinx R, Limet R. Contribution of PET scanning to the evaluation of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Semin Vasc Surg. 2004;17:144–153. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Krupnick AS, Lombardi JV, Engels FH, et al. 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography as a novel imaging tool for the diagnosis of aortoenteric fistula and aortic graft infection--a case report. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2003;37:363–366. doi: 10.1177/153857440303700509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Defawe OD, Hustinx R, Defraigne JO, Limet R, Sakalihasan N. Distribution of F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (F-18 FDG) in abdominal aortic aneurysm: high accumulation in macrophages seen on PET imaging and immunohistology. Clin Nucl Med. 2005;30:340–341. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000159681.24833.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Davison JM, Montilla-Soler JL, Broussard E, et al. F-18 FDG PET-CT imaging of a mycotic aneurysm. Clin Nucl Med. 2005;30:483–487. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000167663.17630.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Defawe OD, Thiry A, Lapiere CM, Limet R, Sakalihasan N. Primary sarcoma of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31:117–119. doi: 10.1007/s00261-005-0366-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Choi SJ, Lee JS, Cheong MH, Byun SS, Hyun IY. F-18 FDG PET/CT in the management of infected abdominal aortic aneurysm due to Salmonella. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33:492–495. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31817793a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.van Assen S, Houwerzijl EJ, van den Dungen JJ, Koopmans KP. Vascular graft infection due to chronic Q fever diagnosed with fusion positron emission tomography/computed tomography. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:372. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Menezes LJ, Kotze CW, Hutton BF, et al. Vascular inflammation imaging with 18F-FDG PET/CT: when to image? J Nucl Med. 2009;50:854–857. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.061432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Reeps C, Essler M, Pelisek J, et al. Increased 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in abdominal aortic aneurysms in positron emission/computed tomography is associated with inflammation, aortic wall instability, and acute symptoms. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.03.059. discussion 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Truijers M, Kurvers HA, Bredie SJ, Oyen WJ, Blankensteijn JD. In vivo imaging of abdominal aortic aneurysms: increased FDG uptake suggests inflammation in the aneurysm wall. J Endovasc Ther. 2008;15:462–467. doi: 10.1583/08-2447.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Truijers M, Pol JA, Kurvers H, et al. Incidental finding of malignancy in patients preoperatively evaluated for aneurysm wall pathology using PET/CT. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:1313–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Wasselius J, Malmstedt J, Kalin B, et al. High 18F-FDG Uptake in synthetic aortic vascular grafts on PET/CT in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1601–1605. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.053462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kotze CW, Menezes LJ, Endozo R, et al. Increased metabolic activity in abdominal aortic aneurysm detected by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;38:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Choke E, Cockerill G, Wilson WR, et al. A review of biological factors implicated in abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;30:227–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Workman P. The impact of genomic and proteomic technologies on the development of new cancer drugs. Ann Oncol. 2002;4(13 Suppl):115–124. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wulfkuhle J, Espina V, Liotta L, Petricoin E. Genomic and proteomic technologies for individualisation and improvement of cancer treatment. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:2623–2632. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Choke E, Thompson MM, Jones A, et al. Gene expression profile of abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1085:311–314. doi: 10.1196/annals.1383.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Cai W, Chen X. Multimodality molecular imaging of tumor angiogenesis. J Nucl Med. 2008;2(49 Suppl) doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045922. 113S–28S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Cai W, Niu G, Chen X. Imaging of integrins as biomarkers for tumor angiogenesis. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:2943–2973. doi: 10.2174/138161208786404308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Tait JF. Imaging of apoptosis. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1573–1576. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.052803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Rudd JH, Fayad ZA. Imaging atherosclerotic plaque inflammation. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;2(5 Suppl):S11–S17. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Rudd JH, Hyafil F, Fayad ZA. Inflammation imaging in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1009–1016. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.165563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Cai W, Chen X. Nanoplatforms for targeted molecular imaging in living subjects. Small. 2007;3:1840–1854. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Hong H, Gao T, Cai W. Molecular imaging with single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nano Today. 2009;4:252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]