Abstract

Objective

The subjective experience of loss of control (LOC) during eating, independent of overeating, may be a salient marker of disordered eating and risk for overweight in youth. However, few studies have directly tested this notion in an adequately powered sample.

Method

Three-hundred-sixty-seven youth (M±SD age=12.7±2.8y) were categorized as reporting objective binge eating (OBE; 12.5%), subjective binge eating (SBE; 11.4%), objective overeating without LOC (OO; 18.5%), or no episodes (NE; 57.5%). Disordered eating attitudes, general psychopathology, and adiposity were assessed.

Results

Children with OBE and SBE generally did not differ in their disordered eating attitudes, emotional eating, eating in the absence of hunger, depressive and anxiety symptoms, or adiposity. However, both OBE and SBE youth had significantly greater disordered eating attitudes, emotional eating, eating in the absence of hunger, depressive and anxiety symptoms, and adiposity compared to those with OO or NE (ps<.05).

Conclusion

For non-treatment-seeking youth, LOC during eating episodes, rather than episode size, appears to be the most salient marker of eating and weight problems.

Keywords: Child, Adolescent, Binge Eating, Loss of Control Eating, Obesity

Binge eating, defined as overeating an objectively large amount of food while experiencing a lack of control over what or how much is being eaten, is the core symptom of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder (BED).1 Although few children and adolescents meet full DSM-IV-R criteria for bulimia nervosa or the proposed research criteria for BED, the prevalence of binge eating behavior among school and community samples of children and adolescents is high, with estimates ranging from approximately 6% to 40%.2–7

The assessment of binge eating behavior in youth is complicated by difficulty in determining what constitutes an objectively large amount of food in developing children with varying nutritional needs. Thus, a number of research groups have opted to study the experience of loss of control (LOC) over what or how much is being eaten, regardless of the reported episode size. Objective binge eating (OBE) refers to episodes during which individuals report LOC while consuming an objectively, unambiguously large amount of food. Subjective binge eating (SBE) refers to episodes during which individuals perceive excessive consumption with LOC, but the amount consumed is not objectively large.8 Estimates of LOC eating among non-treatment seeking youth are substantial, ranging from approximately 4% to 33%.9–15

The experience of LOC itself, apart from the reported amount of food consumed, appears to be a salient marker of pediatric disordered eating. Studies examining children and adolescents' LOC eating have found that youth who report the presence of at least one episode of SBE or OBE in the month prior to assessment have greater disordered eating cognitions and behaviors as well as greater depressive and anxiety symptoms than those who report no such episodes.10,11,14 Pediatric LOC eating also may be a risk factor for excessive weight gain. Children with LOC are more likely to be overweight and to have greater body fat mass than their counterparts without LOC eating.10,11,14,16 Among 6 to 13 year-old children, those who report at least one episode of LOC in the month prior to assessment have been found to gain an additional 2.4 kg of weight per year over 4–5 years than children who do not report LOC.17 Laboratory observations of children and adolescents' food intake suggest that those with LOC may be susceptible to greater weight gain in part because they consume more energy-dense palatable foods such as desserts and snacks.18

Despite the available evidence supporting the salience of LOC for pediatric binge eating episodes, it is not yet well understood whether the reported size of LOC eating episodes (i.e., SBE versus OBE) is relevant for distinguishing the degree of disordered eating pathology, associated general psychopathology, and risk for higher body fat among youth. Based on current DSM-IV-TR criteria for a binge eating episode,1 it is often an assumption that those who report OBE have more psychopathology than those who only report SBE. However, a number of adult studies suggest that LOC, rather than the episode size distinction, may be most central to identifying psychological disturbance among adults with eating disorders or obesity.19–23 Nevertheless, among youth, weight-loss treatment-seeking, obese adolescents who meet full symptom criteria for BED have greater disordered eating attitudes, more negative mood, and higher anxiety than youth reporting sub-threshold OBE or SBE.24 To our knowledge, only one pediatric study13 has directly compared the associations of SBE and OBE with psychopathology and disordered eating attitudes among children and adolescents. In an obese, treatment-seeking sample, a small subset of youth with SBE (n=15) had eating concern, shape concern, and emotional and external eating scores intermediate between those of youth with OBE (n=20) and those with no LOC eating (n=161).13 Youth with SBE differed significantly from those with OBE or from those reporting no LOC eating only in their frequency of emotional eating.13 Further investigation into whether episode size matters for pediatric LOC eating episodes is thus needed.

To our knowledge, no study has directly compared SBE and OBE and their correlates in a non-treatment-seeking sample of children of adolescents that is adequately powered to detect significant differences. Such a comparison is especially warranted. In non-treatment-seeking pediatric populations, youth who report LOC typically report only one recent episode (e.g., once in the past month) and also, only one type of episode (i.e., either OBE or SBE).8 Understanding possible similarities or differences in the psychological and anthropometric characteristics of such youth with OBE versus SBE has potential to inform preventative approaches by possibly identifying those at particular risk for future development of BED or obesity.

The objective of the current study was to compare non-treatment-seeking youth with no reported episodes of overeating (NE), objective overeating without a sense of LOC (OO), SBE, and OBE in their body composition, disordered eating attitudes and behaviors, and general psychopathology. Based on the notion that LOC may be the most salient marker of aberrant eating episodes in youth, we hypothesized that youth with either type of LOC eating (SBE or OBE) would have greater body fat, disordered eating, and general psychopathology than youth with NE or OO. Further, we expected that youth with SBE or OBE would have similar scores on measures of body composition, disordered eating, and general psychopathology.

Methods

Participants

Children and adolescents (6–17 years) who were participating in non-intervention metabolic and eating study protocols (ClinicalTrials.gov IDs: NCT00320177, NCT00001522, NCT00631644) were included. Psychological and body composition data from 26% of the total sample has been published in prior studies;14,15,25 the majority (74%) has not been the subject of previous publication. Participants were recruited through posted flyers, mailings to parents in the Montgomery County and Prince George's County, MD school districts, and mailings to local family physicians and pediatricians requesting children willing to participate in studies investigating hormones, growth, and eating patterns in youth. Individuals were excluded if they had a significant medical condition, abnormal hepatic, renal, or thyroid function, were taking medication known to impact body weight, or had a psychiatric disorder that might impede protocol compliance. Pregnant girls were not eligible for the study, nor were children who had lost more than 5% of their body weight in the 3 months prior to assessment or who were undergoing weight loss treatment. The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development institutional review board approved all clinical protocols. Children and their parents' written informed assent and consent for participation were obtained.

Procedure and Assessment

Participants were seen at the National Institutes of Health Warrant Grant Magnuson Clinical Center (Bethesda, MD) following an overnight fast. All youth underwent a medical history and a physical examination conducted by a pediatric endocrinologist or a trained pediatric nurse practitioner. Each child subsequently participated in interview and questionnaire measures of disordered eating pathology, symptoms of general psychopathology, and body composition. A parent also completed measures of children's eating behavior and internalizing and externalizing problems.

Interview Assessment of Loss of Control (LOC) Eating

The Eating Disorder Examination version 12OD/C.2 (EDE)26 or the EDE adapted for children (children age<14 years)27 was administered by trained interviewers to each participant to determine the presence or absence in the month prior to assessment of four types of eating episodes. Participants were categorized as: i) those who reported OBE if they endorsed at least one episode of unambiguous overeating with a sense of lack of control over their eating; ii) those who reported SBE if they reported no OBE, but reported at least one episode of perceived overeating with LOC, but the amount was not viewed as objectively large by the interviewer; iii) those reporting OO if they reported overeating without LOC and reported no episodes of OBE or SBE; or iv) those with no reported episodes (NE) of either overeating or LOC. The EDE has good inter-rater reliability for all episode types (Spearman correlation coefficients: ≥0.70).24,28 Tests of the child EDE have demonstrated good inter-rater reliability (Spearman rank correlations from 0.91–1.00) and discriminant validity in eating disorder samples and matched controls ages 8–14 years.29 Among non-overweight and overweight 6 to 13 year-olds, the child EDE revealed excellent inter-rater reliability with a Cohen's kappa for presence of the different eating episode categories of 1.00 (p<0.001).14 For the current study, interviewers met weekly to review eating episodes.

The EDE also generates four subscales, restraint, eating concern, shape concern, and weight concern, as well as a global score. These continuous variables were used as measures of children and adolescents' disordered eating attitudes. As described previously,14 variables generating the subscales are independent of those identifying eating episodes.

Youth Self-Report of Eating Behavior and General Psychopathology

Participants' perceptions of their emotional eating were assessed by their report on the Emotional Eating Scale adapted for use in children and adolescents (EES-C).15 Children rated their desire to eat in response to emotions on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0=“I have no desire to eat” to 4=“I have a very strong desire to eat.” The EES-C is comprised of three factor-analytically derived subscales: i) eating in response to depressive symptoms (EES-C-DEP; 10 items), ii) eating in response to anger, anxiety, and frustration (EES-C-AAF; 14 items), and iii) eating in response to feeling unsettled (EES-C-UNS; 4 items). The EES-C has demonstrated sound convergent and discriminant validity and test-retest reliability for assessing emotional eating in youth.15

Participants reported on their perceived eating in the absence of hunger on the Eating in the Absence of Hunger Questionnaire for Children (EAH-C).25 The EAH-C consists of 14 total items from which three subscales are factor-analytically derived: i) Negative Affect (6 items), ii) External Eating (4 items), and iii) Fatigue/Boredom (4 items). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0=“never” to 4=“always.” The measure has demonstrated good internal consistency, convergent validity and temporal stability for all scales.25

Participants completed the Children's Depression Inventory (CDI), a reliable and well-validated 27-item self-rated measure of depressive symptoms.30 The total score was used. They also completed the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) A—Trait Scale (STAI-C), a 20-item self-report measure of trait anxiety that is widely used and psychometrically sound.31

Parent Report of Children's Eating Behavior and General Psychopathology

Parents reported on their perceptions of their children's eating in the absence of hunger on a parallel version of the EAH-C for parents (EAH-P). The same factor-analytically derived, internally reliable subscales (Negative Affect, External Eating, and Fatigue/Boredom) were used. Parents also completed the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 4–18,32 an empirically derived measure with excellent norms. The Internalizing and Externalizing Scales were examined as measures of children's symptoms of general psychopathology.

Body Composition

Each participant's fasting weight and height was measured using calibrated electronic instruments as described previously.33 Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. BMI standard deviation scores (BMI-z) for age and sex were calculated according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts.34

Children's body fat mass (kg) was measured either by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) using Hologic QDR-2000 or Hologic QDR 4500A equipment (Hologic, Waltham, MD) or air displacement plethysmography (Bod Pod; Life Measurement Inc., Concord, CA) as previously described.14,33 As recommended, we ensured that measurements of adiposity were equivalent between the two different assessment techniques by adding 2.29 kg to DXA fat mass obtained using the 4500A machine and multiplying girls' Bod Pod fat mass by 1.03.35,36

To assess pubertal stage, female breast development was assigned through physical examination by a pediatric endocrinologist or trained pediatric nurse practitioner according to one of the five stages of Tanner.37,38 Testicular volume (in cc) for males was measured using an orchidometer.39

Data Analytic Plan

Descriptive information was generated on all study variables for each eating episode group (i.e., NE, OO, SBE, and OBE). Analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were used to investigate comparisons among the four eating episode groups on the dependent measures of body composition, disordered eating attitudes and behaviors, and general psychopathology. As recommended,40,41 two-tailed, least squares difference tests were used to follow up on a priori, planned comparisons between groups. Age, sex, race, puberty, and fat mass (kg) were included as covariates in analyses examining group differences in disordered eating attitudes and behaviors and general psychopathology. The same covariates, other than fat mass, were accounted for in analyses examining group differences in body composition. Additionally, we adjusted for height (cm) in the analysis of fat mass. Power analyses conducted with nQuery42 indicated that a sample size of 25 per group was needed to detect significant differences among groups with 80% power. Differences between groups were considered significant when p probability values were <.05. All analyses were performed with SPSS 16.0.43

Results

Descriptive Information

Participants were 176 girls (48%) and 191 boys between the ages of 6 and 17 years (M±SD 12.7±2.8 years). Sample demographics are presented in Table 1. Based on participants' responses to the EDE, none met diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or BED. Just over half (57.5%, n=211) endorsed NE, 18.5% (n=68) reported OO, 11.4% (n=42) reported SBE, and 12.5% (n=46) reported OBE. Of children reporting OO, the frequency of episodes in the past month ranged from 1–22, with the majority (68.4%) reporting one OO episode. Of those reporting SBE, the frequency of episodes ranged from 1–15, with just over half (54.1%) reporting one SBE episode in the past month. The frequency of OBE episodes ranged from 1–28, with the vast majority (71.7%) reporting one episode in the past month. A minority of the total sample reported more than one episode type: 4.3% (n=16) reported both ≥1 SBE and ≥1 OBE, 1.6% (n=6) reported ≥1 OBE and ≥1 OO, and 0.8% (n=3) reported ≥1 SBE and ≥1 OO. Youth were categorized as those reporting OBE regardless of whether they reported another type of episode, and they were categorized as those reporting SBE regardless of whether or not they also reported an OO episode. Comparison of the subset with both ≥1 SBE and ≥1 OBE to those with SBE only or OBE only revealed no significant differences among groups on any measure. Eating episode group showed a significant relationship with sex (χ2=9.76, p=.02) such that a greater percentage of girls than boys comprised the SBE (61.9%) and OBE (60.9%) groups compared to the NE (41.7%) and OO groups (50.0%). Eating episode group was not related to age, race, puberty, or SES (ps>.20).

Table 1.

Sample demographic and anthropometric characteristics

| NE (n=211) | OO (n=68) | SBE (n=42) | OBE (n=46) | F or χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y)1 | 12.5±.19 | 13.0±.35 | 13.4±.42 | 12.6±.39 | 1.56 | .199 |

| Sex (% Female) | 41.7% | 50.0% | 61.9% | 60.9% | 9.76 | .021 |

| Race (% Non-Hispanic White) | 60.7% | 57.4% | 52.4% | 50.0% | 2.37 | .500 |

| Puberty (Median, Range)2 | 3, 1–5 | 4, 1–5 | 4, 1–5 | 3, 1–5 | 15.05 | .658 |

| SES (Median, Range)3 | 2, 1–5 | 3, 1–5 | 2, 1–5 | 2, 1–4 | 9.03 | .700 |

| BMI-z1,4 | .84±.08 | .96±.13 | 1.38±.15 | 1.44±.18 | 5.04 | .002 |

| Total body fat mass (kg)1,5 | 19.4±1.2 | 17.5±1.7 | 24.1±2.0 | 28.3±3.2 | 4.86 | .003 |

Mean±SE.

For puberty, NE n=201; OO n=67; SBE n=41; OBE n=45.

Socioeconomic status (SES) was assessed with the Hollingshead Index.53 For SES, NE n=199; OO n=66; SBE n=44.

For BMI-z, OBE n=45.

For total body fat mass, NE n=210; OO n=65; SBE n=40.

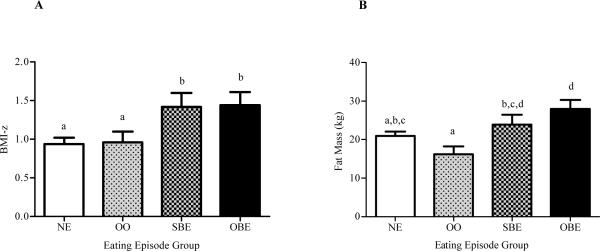

Body Composition

When comparing youth endorsing NE, OO, SBE, and OBE, significant, overall differences were observed in both BMI-z (p=.008) and fat mass (p=.002; Table 1). As shown in Figure 1A, both OBE (M±SE=1.44±.17) and SBE (1.42±.18) youth had higher BMI-z scores than NE (.94±.08) and OO youth (.96±.14, ps<.04), adjusting for covariates. BMI-z scores of OBE and SBE youth did not differ significantly (p=.92), nor did BMI-z scores of NE and OO youth differ (p=.90). As Figure 1B depicts, after adjusting for covariates, OBE (27.99±2.37) and SBE (23.93±2.53) youth had more body fat mass than OO youth (16.17±2.06; ps<.02), and OBE youth had higher fat mass than NE youth (20.94±1.15, p=.008). There was also a significant difference in fat mass between OO and NE youth (p=.045), but SBE and OBE youths' fat mass did not differ (p=.24).

Figure 1.

A: BMI-z and B: total body fat mass among youth who report neither overeating nor loss of control (NE), overeating without loss of control (OO), subjective binge eating (SBE), and objective binge eating (OBE). Analysis for BMI-z was adjusted for age, sex, race, and puberty; analysis for fat mass was adjusted for these covariates as well as for height. Significant differences (p<.05) are indicated by different subscripts.

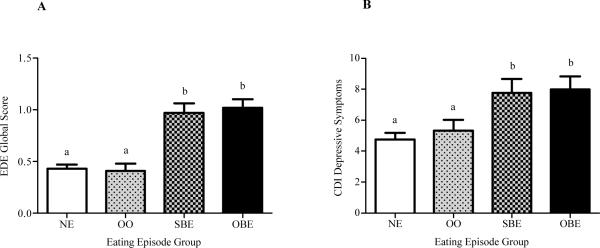

Youth Reports of Disordered Eating Attitudes and Behaviors

When EDE global and subscale scores were examined based upon eating episode group, significant, overall group differences were observed on all scales (ps< .001; Table 2). After adjustment for covariates, both SBE and OBE youth had higher global disordered eating attitudes (ps<.001; Figure 2A), restraint (ps<.007), shape concern (ps <.001), eating concern (ps<.001), and weight concern (ps<.001) than those with NE or OO. SBE and OBE youth did not significantly differ on global (p=.20), restraint (p=.92), shape concern (p=.19), and weight concern (p=.29) scales. However, OBE youth had slightly, but significantly, greater eating concern than youth with SBE (p=.04). Children and adolescents with NE and OO did not significantly differ from each other on any EDE scale (ps>.70).

Table 2.

Comparisons among youth who report NE, OO, SBE, and OBE on measures of youth reported disordered eating and general psychopathology

| NE (n=199) | OO (n=64) | SBE (n=38) | OBE (n=45) | F or χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disordered Eating 1 | ||||||

| EDE global | .43±.04a | .41±.07a | .97±.09b | 1.02±.08b | 21.79 | <.001 |

| EDE restraint | .40±.05a | .38±.08a | .81±.11b | .75±.10b | 6.45 | <.001 |

| EDE eating | .09±.03a | .10±.05a | .43±.06b | .54±.06c | 26.03 | <.001 |

| EDE shape | .53±.06a | .49±.11a | 1.32±.14b | 1.41±.13b | 20.52 | <.001 |

| EDE weight | .70±.06a | .66±.11a | 1.32±.14b | 1.37±.13b | 11.79 | <.001 |

| EAH-C-Negative Affect2 | 1.37±.05a | 1.36±.10a | 1.87±.10b | 1.69±.11b | 8.20 | <.001 |

| EAH-C-Fatigue/Boredom2 | 1.64±.08a | 1.86±.14a,d | 2.36±.14b | 2.06±.16b,d | 7.43 | <.001 |

| EAH-C-External Eating2 | 2.47±.08a | 2.61±.13a,b | 2.84±.14b | 2.86±.16b | 2.90 | .036 |

| EES-C-Depression3 | .70±.07a | .67±.12a | 1.14±.13b | 1.27±.14b | 7.23 | <.001 |

| EES-C- Ang/Anx/Frustration3 | .48±.06a | .44±.11a | .79±.11b | .90±.12b | 4.88 | .003 |

| EES-C-Unsettled3 | .62±.06a | .67±.12a,b | .85±.12a,b | .99±.13b | 2.65 | .050 |

| General Psychopathology 1 | ||||||

| CDI4 | 4.76±.41a | 5.33±.68a | 7.76±.91b | 7.99±.85b | 5.83 | .001 |

| STAI-C5 | 29.87±.53a | 30.27±.87a | 33.30±1.19b | 34.98±1.11b | 7.13 | <.001 |

Mean±SE.

For EAH-C scales, NE n=120; OO n=38; SBE n=35; OBE n=27.

For EES-C scales, NE n=128; OO n=38; SBE n=35; OBE n=32.

For the CDI, NE n=164; OO n=59; SBE n=32; OBE n=38.

For the STAI-C, NE n=161; OO n=59; SBE n=31; OBE n=37.

All estimates are adjusted for age, sex, race, puberty, and fat mass (kg).

Significant differences (p <.05) in pairwise least squares difference comparisons are indicated by different subscripts.

Figure 2.

A: Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) global disordered eating attitudes and B: Children's Depression Inventory (CDI) depressive symptoms among youth who report neither overeating nor loss of control (NE), overeating without loss of control (OO), subjective binge eating (SBE), and objective binge eating (OBE). Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, race, puberty, and fat mass. Significant differences (p<.05) are indicated by different subscripts.

Eating episode group also was significantly related to youths' self-reports of eating in the absence of hunger on the EAH-C (ps<.04; Table 2). EAH-C-Negative Affect scores were higher among both SBE and OBE youth compared to NE or OO youth (ps<.03), and EAH-C-Fatigue/Boredom and EAH-C-External Eating scores were higher among SBE and OBE youth compared to those with NE (ps<.03). SBE youth scored higher on EAH-C-Fatigue/Boredom than OO youth (p=.02). Children and adolescents with SBE and OBE did not differ significantly (ps>.16), nor did youth with NE and OO (ps>.34) differ significantly, on any EAH-C scale.

With regard to emotional eating, the eating episode groups also differed significantly (ps<.04; Table 2). EES-C-DEP and EES-C-AAF scores were higher among both SBE and OBE youth compared to NE and OO youth (ps<.03; Table 2). There were no significant differences between SBE and OBE youth (ps>.47), nor between NE and OO youth (ps>.77). On the EES-CUNS scale, the only significant difference was that children and adolescents reporting OBE scored higher than those reporting NE (p=.01).

Youth Reports of Symptoms of General Psychopathology

When youths' self-reported depressive and anxiety symptoms were examined by eating episode group, significant, overall differences were observed on both measures (ps<.001; Table 2). SBE and OBE youth self-reported higher depressive (ps<.05; Figure 2B) and anxiety (ps<.05) symptoms than their counterparts with NE and OO. SBE and OBE youth did not differ significantly (ps>.37), nor did those with NE and OO differ on depressive or anxiety symptoms (ps>.51).

Parent Reports of Child Eating Attitudes

Parent-reported eating in the absence of hunger scales were overall, significantly different among eating episode groups (ps<.001; Table 3). After accounting for covariates, parents of OO, SBE, and OBE youth reported higher EAH-P-Negative Affect (p=.009) and EAH-P-Fatigue/Boredom (p=.025) than parents of NE youth. EAH-P-External Eating scores were highest among OO youth. Parents of OO youth (p<.001) and SBE youth (p=.006) reported greater EAH-P-External Eating scores compared to parents of youth with NE. Also, parents of OO youth reported higher EAH-P-External Eating scores than parents of OBE youth (p=.028).

Table 3.

Comparisons among youth who report NE, OO, SBE, and OBE on measures of parent reported disordered eating and general psychopathology

| NE (n=186) | OO (n=62) | SBE (n=37) | OBE (n=45) | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disordered Eating1,2 | ||||||

| EAH-P-Negative Affect | 1.28±.06a | 1.66±.10b | 1.78±.10b | 1.64±.12b | 8.44 | <.001 |

| EAH-P Fatigue/Boredom | 1.54±.07a | 1.86±.12b | 2.05±.12b | 1.89±.14b | 5.89 | .001 |

| EAH-P-External Eating | 2.41±.07a, | 2.95±.12b | 2.82±.13b,c | 2.52±.15a,c | 6.23 | <.001 |

| General Psychopathology 1 | ||||||

| CBCL-Internalizing | 45.75±.80a | 49.28±1.36b | 48.01±1.76a,b | 50.17±1.62b | 3.02 | .030 |

| CBCL-Externalizing | 45.96±.78a | 49.31±1.33b | 45.05±1.73a | 48.39±1.59a,b | 2.27 | .080 |

Mean±SE.

For EAH-P scales, NE n=120; OO n=38; SBE n=35; OBE n=26.

All estimates are adjusted for age, sex, race, puberty, and fat mass (kg).

Significant differences (p <.05) in pairwise least squares difference comparisons are indicated by different subscripts.

Parent Reports of Child Internalizing and Externalizing Symptoms

Examining parents' reports of general psychopathology among children endorsing NE, OO, SBE, and OBE, significant, overall differences were observed on internalizing symptoms (p=.03), but not on externalizing symptoms (p=.08; Table 3). Adjusting for covariates, parents of both overeating groups, regardless of LOC experiences (i.e, OO and OBE youth) reported greater child internalizing symptoms than parents of NE youth (ps<.03). No other significant differences were observed with regard to internalizing symptoms.

Post-Hoc Exploratory Analyses

We conducted a series of exploratory follow-up analyses to examine whether age or sex moderated the associations between eating episode group and body composition, disordered eating attitudes and behaviors, or general psychopathology by adding these interactions terms to each model. The observed effects were remarkably consistent across age levels, with 19 out of 20 tests insignificant for an age by eating episode group interaction. Similarly, the observed effects were highly consistent across sex, with 18 out of 20 tests insignificant for a sex by eating episode group interaction.

Also, given the low frequency criterion (≥1 episode in the past month) for assignment to OO, SBE, and OBE categories, we conducted a series of follow-up analyses to explore whether the observed patterns persisted at higher frequencies (≥2 episodes in the past month). Using the same ANCOVA models, we compared body composition, disordered eating, and general psychopathology among youth with NE (n=199), ≥2 OBE episodes (n=18), ≥2 SBE episodes (n=23), or ≥2 OO (n=18) episodes. Although these analyses were underpowered, the results were almost identical to the primary analyses across all domains.

Discussion

It has been theorized that loss of control (LOC) is a more salient marker of pediatric binge eating episodes than the reported amount of food consumed during such episodes.8 Yet, direct tests of this notion are scant. In the present study, we compared a sizeable, adequately powered sample of children and adolescents who were categorized by eating episode size and whether or not LOC was reported. Consistent with our hypotheses, youth with both types of LOC eating exhibited greater disordered eating attitudes and behaviors than youth reporting OO or NE. It is especially notable that relative to children and adolescents with NE or OO, those who reported either SBE or OBE displayed heightened levels of body shape and weight concerns, which have been shown to be prospective risk factors for the development of partial or full syndrome eating disorders.44,45

Compared to their peers with NE or OO, youth who reported either SBE or OBE reported greater emotional eating in response to depressive symptoms and feelings of anger/anxiety/frustration, more frequent eating in the absence of hunger in response to negative affect, and higher depressive and anxiety symptoms. Such associations are congruent with prior data illustrating relationships between pediatric LOC eating and emotional eating, eating in the absence of hunger, and general psychopathology.10,11,15,25

These observed patterns are consistent with affective theories of binge eating, which propose that LOC may occur as a consequence of attempts to alleviate temporary or chronic negative affect.46 Indeed, negative affect has been shown to predict increases in bulimic symptoms, including OBE, in children and adolescents.2,47–49 Although results from the present study are cross-sectional and cannot be construed to imply causation, our data suggest that future studies should examine the effects of negative affect on LOC, SBE, and/or OBE longitudinally.

The current findings clearly delineate that, in a non-treatment seeking sample of youth, the subjective experience of low-frequency LOC, regardless of the reported amount of food consumed, is consistently tied to greater negative affective experiences and reports of eating in response to such emotional distress. The presence of LOC, regardless of the reported size of food intake, may be a particularly important indicator of risk for disordered eating attitudes and behaviors and general psychopathology in youth for several reasons. Foremost, children often do not have the same kind of independent access to food as adults, which may put a ceiling on the amount of food they would otherwise consume during an episode of LOC eating.8 Another consideration is that youth, especially those who are overweight, tend to underreport their food intake.50 Since classification of SBE versus OBE often relies on children's self-reports, it is possible that youth who report consuming an amount of food that is ambiguously large may actually be eating a larger amount of food that would constitute an OBE. Indeed, this explanation is supported by our findings that youth who reported SBE or OBE had similar body composition to each other and greater BMI-z scores and adiposity than youth who reported either OO or NE. Additionally, binge eating behaviors in youth can be difficult to assess because it can be challenging to determine what constitutes an unambiguously large amount of food in developing boys and girls of different ages and pubertal stages.8 For example, reported consumption of two large hamburgers, a large order of French fries, and a large soft drink, might be considered unambiguously large for a pre-pubertal 8-year-old girl; however, the size classification of the same reported amount of food consumed would be much more ambiguous in a 15-year-old boy in the midst of a growth spurt.

Interestingly, examination of parents' reports revealed a pattern that was somewhat discrepant from youths' self-reports. On comparisons of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors, parents of children with the presence of any type of eating episode (i.e., OO, SBE, or OBE) rated their children higher on eating in the absence of hunger in response to negative affect and fatigue/boredom than parents of youth with NE. Further, OO youth were distinguished by the highest parent-perceived eating in the absence of hunger in response to external cues. In terms of symptoms of general psychopathology, OO and OBE youths' parents reported the greatest internalizing symptoms. Judging from parents' perspectives, it is plausible that children who experience overeating with or without LOC may be at elevated risk for disordered eating and general psychopathology compared to children's whose eating is comparatively normative. Such a possible explanation fits with research suggesting that overweight youth have greater overall disordered eating behaviors and attitudes and parent-reported behavioral problems than non-overweight youth.14 Alternatively, it is quite likely that parents may be better observers of objective over-consumption than of their children's internal experiences of LOC. In turn, parents may infer their child's internal experience based on these objective observations. Consistent with this notion are studies finding that parents and youth show little agreement on reports of child eating behavior51 or psychosocial problems, especially for internalizing symptoms.52

The current study findings should be considered in light of its limitations. All data were cross-sectional and correlational, thus the causal direction of any relations cannot be established. Prospective examinations of youth with NE, OO, SBE, and OBE and their disordered eating, general psychopathology, and weight outcomes are necessary for truly distinguishing whether LOC itself is the most salient marker of risk for disordered eating and obesity. Also, it is important to note that although measures of psychological symptomatology among youth with LOC were higher relative to the other eating groups in the sample, they did not reach levels that elicit clinical concern. Nonetheless, subclinical levels of disordered eating pathology have been shown to predict future clinically relevant disordered eating.45,47 Finally, the current study classified youth based on the presence or absence of ≥1 episode of OO, SBE, or OBE in the month prior to assessment. Although this classification scheme is commonly employed and may be most appropriate among non-treatment seeking youth who primarily report only one episode,16 frequency of SBE or OBE episodes appears to play an important role, at least among weight-loss treatment-seeking obese samples of youth.13,24 Regardless, it is noteworthy that the current findings were replicated when we limited analyses to youth with ≥2 recent eating episodes.

One strength of the current study was the administration of the EDE to a large sample of youth with enough participants who reported SBE or OBE episodes that the study was adequately powered to detect potential differences. A second strength was the comparison of pediatric eating episode types with multiple youth self-reports, parent reports, and objective measurements. Although binge eating behaviors in adults have been extensively studied, the investigation of children's binge eating behaviors is an emerging field.8 Results from the current study may help to guide the research on pediatric binge eating in non-treatment-seeking samples by demonstrating that the assessment of subjective LOC over eating may be one of the most salient markers of disordered eating and overweight risk in youth.

Acknowledgments

Research support: Intramural Research Program, NIH, grant Z01-HD-00641 (to J. Yanovski) from the NICHD, supplemental funding from NCMHD and OBSSR (to J. Yanovski), USUHS grant R072IC (to M. Tanofsky-Kraff), and NICHD National Research Service Award 1F32HD056762 (to L. Shomaker).

Footnotes

The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edition Washington, D.C.: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Field AE, Camargo CA, Taylor CB, et al. Overweight, weight concerns, and bulimic behaviors among girls and boys. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(6):754–60. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Resnick MD, Blum RW. Psychosocial concerns and weight control behaviors among overweight and nonoverweight Native American adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;97(6):598–604. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson WG, Rohan KJ, Kirk AA. Prevalence and correlates of binge eating in white and African American adolescents. Eat Behav. 2002;3(2):179–89. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(01)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenfeld D, Quinlan DM, Harding P, Glass E, Bliss A. Eating behavior in an adolescent population. Int J Eat Disord. 1987;6:99–111. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croll J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Ireland M. Prevalence and risk and protective factors related to disordered eating behaviors among adolescents: relationship to gender and ethnicity. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(2):166–75. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Downes B, Resnick M, Blum R. Ethnic differences in psychosocial and health behavior correlates of dieting, purging, and binge eating in a population-based sample of adolescent females. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;22(3):315–22. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199711)22:3<315::aid-eat11>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanofsky-Kraff M. Binge eating among children and adolescents. In: Jelalian E, Steele R, editors. Handbook of Child and Adolescent Obesity. Springer; 2008. pp. 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Decaluwe V, Braet C. Prevalence of binge-eating disorder in obese children and adolescents seeking weight-loss treatment. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(3):404–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan CM, Yanovski SZ, Nguyen TT, et al. Loss of control over eating, adiposity, and psychopathology in overweight children. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;31(4):430–41. doi: 10.1002/eat.10038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Faden D, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Yanovski JA. The perceived onset of dieting and loss of control eating behaviors in overweight children. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38(2):112–22. doi: 10.1002/eat.20158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine MD, Ringham RM, Kalarchian MA, Wisniewski L, Marcus MD. Overeating among seriously overweight children seeking treatment: results of the children's eating disorder examination. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39(2):135–40. doi: 10.1002/eat.20218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goossens L, Braet C, Decaluwe V. Loss of control over eating in obese youngsters. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Marmarosh C, Morgan CM, Yanovski JA. Eating-disordered behaviors, body fat, and psychopathology in overweight and normal-weight children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:53–61. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Theim KR, Yanovski SZ, et al. Validation of the Emotional Eating Scale adapted for use in children and adolescents (EES-C) Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(3):232–40. doi: 10.1002/eat.20362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Goossens L, Eddy KT, et al. A multisite investigation of binge eating behaviors in children and adolescents. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2007;75(6):901–13. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Schvey NA, Olsen CH, Gustafson J, Yanovski JA. A prospective study of loss of control eating for body weight gain in children at high risk for adult obesity. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42(1):26–30. doi: 10.1002/eat.20580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanofsky-Kraff M, McDuffie JR, Yanovski SZ, et al. Laboratory assessment of the food intake of children and adolescents with loss of control eating. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(3):738–45. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colles SL, Dixon JB, O'Brien PE. Loss of control is central to psychological distrubance associated with binge eating disorder. Obesity. 2008;16(3):608–14. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Latner JD, Hildebrandt T, Rosewall JK, Chisholm AM, Hayashi K. Loss of control over eating reflects eating distrubances and general psychopahtology. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(9):2203–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niego SH, Pratt EM, Agras WS. Subjective or objective binge: is the distinction valid? Int J Eat Disord. 1997;22(3):291–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199711)22:3<291::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pratt EM, Niego SH, Agras WS. Does the size of a binge matter? Int J Eat Disord. 1998;24(3):307–12. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199811)24:3<307::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerzhnerman I, Lowe MR. Correlates of subjective and objective binge eating in binge-purge syndromes. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;31(2):220–8. doi: 10.1002/eat.10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glasofer DR, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Eddy KT, et al. Binge eating in overweight treatment-seeking adolescents. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2007;32(1):95–105. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Ranzenhofer LM, Yanovski SZ, et al. Psychometric properties of a new questionnaire to assess eating in the absence of hunger in children and adolescents. Appetite. 2008;51(1):148–55. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fairburn C, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: CG F, GT W, editors. Binge eating, nature, assessment and treatment. 12th ed. Guilford; New York: 1993. pp. 317–60. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bryant-Waugh RJ, Cooper PJ, Taylor CL, Lask BD. The use of the eating disorder examination with children: a pilot study. Int J Eat Disord. 1996;19(4):391–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199605)19:4<391::AID-EAT6>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rizvi SL, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, Agras WS. Test-retest reliability of the eating disorder examination. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28(3):311–6. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200011)28:3<311::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christie D, Watkins B, Lask B. Assessment. In: Lask B, Bryant-Waugh RJ, editors. Anorexia nervosa and related eating disorders in childhood and adolescence. 2 ed. Psychology Press; East Essex, UK: 2000. pp. 105–25. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kovacs M. The children's depression inventory. 1982. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Achenbach TM, Elderbrock C. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell DL, Keil MF, Bonat SH, et al. The relation between skeletal maturation and adiposity in African American and Caucasian children. J Pediatr. 2001;139:844–48. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.119446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv Data. 2000 Jun;8(314):1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicholson JC, McDuffie JR, Bonat SH, et al. Estimation of body fatness by air displacement plethysmography in African American and white children. Pediatric research. 2001;50(4):467–73. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200110000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robotham DR, Schoeller DA, Mercado AB, et al. Estimates of body fat in children by Hologic QDR-2000 and QDR-4500A dual-energy X-ray absorptiometers compared with deuterium dilution. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2006;42(3):331–5. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000189373.31697.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44:291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45:13–23. doi: 10.1136/adc.45.239.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanner JM. Growth and maturation during adolescence. Nutr Rev. 1981;39:43–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1981.tb06734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen J. Things I have learned (so far) Am Psychol. 1990;45:1304–12. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saville DJ. Multiple comparison procedures: The practical solution. Am Stat. 1990;44:174–80. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Statistical Solutions . nQuery. Boston, MA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 43.SPSS Inc. SPSS 16.0. Chicago, IL: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Killen JD, Hayward C, Wilson DM, et al. Factors associated with eating disorder symptoms in a community sample of 6th and 7th grade girls. Int J Eat Disord. 1994;15:357–67. doi: 10.1002/eat.2260150406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.The McKnight Investigators Risk factors for the onset of eating disorders in adolescent girls: results of the McKnight longitudinal risk factor study. The American journal of psychiatry. 2003;160(2):248–54. doi: 10.1176/ajp.160.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heatherton TF, Baumeister RF. Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychol Bull. 1991;110(1):86–108. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Killen JD, Taylor CB, Hayward C, et al. Weight concerns influence the development of eating disorders: a 4-year prospective study. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1996;64(5):936–40. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stice E. A prospective test of the dual-pathway model of bulimic pathology: mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110:124–35. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stice E, Agras WS. Predicting onset and cessation of bulimic behaviors during adolescence: A longitudinal grouping analysis. Behav Ther. 1998;29:257–76. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fisher JO, Johnson RK, Lindquist C, Birch LL, Goran MI. Influence of body composition on the accuracy of reported energy intake in children. Obes Res. 2000;8(8):597–603. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steinberg E, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Cohen ML, et al. Comparison of the child and parent forms of the Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns in the assessment of children's eating-disordered behaviors. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;36(2):183–94. doi: 10.1002/eat.20022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychol Bull. 1987;101:213–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]