Abstract

An inner-city Emergency Department (ED) visit provides an opportunity for contact with high-risk adolescents for promoting injury prevention.

Objectives

To identify the prevalence of injuries sustained over the past year by teens presenting to an inner city ED, and to identify factors associated with recent injury to inform future ED-based injury prevention initiatives.

Methods

Over one year, seven days a week, from 1:00–11:00 PM, patients ages 14–18 years presenting to the ED participated in a survey regarding past-year risk behaviors and injuries.

Results

Of the entire group of teens presenting to the ED (n=1128) who completed the survey (83.8% response rate), 46% were male, and 58% were African-American. Past-year injuries were reported by 768 (68.1%) of the teens; 475 (61.8%) reported an unintentional injury and 293 (38.1%) reported an intentional injury. One-third of all youth seeking care reported a past-year sports-related injury (34.5%) or an injury related to driving or riding in a car (12.3%), and 8.2% reported a gun-related injury. Logistic regression found binge drinking (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=1.95) and illicit weapon carrying (AOR=2.31) predicted a past-year intentional injury. African American youth (AOR=0.56) and those receiving public assistance (AOR=0.73) were less likely to report past-year unintentional injuries.

Conclusions

Adolescents seeking care in an inner city ED, regardless of reason for seeking care, report an elevated prevalence of recent injury including violence. Future injury screening and prevention efforts should consider universal screening of all youth seeking ED care.

INTRODUCTION

Injuries cause significant morbidity and mortality among teens in the United States (U.S.). Unintentional injury is the leading cause of death for all adolescents.(1) Intentional injury (homicide) is the leading cause of death for African-American adolescents and the second leading cause of death for Caucasian adolescents.(1) More adolescents in the U.S. die as a result of injuries than any other cause.(1)

Injuries are increasingly understood to be highly preventable occurrences.(2) In 2004, 71% of mortality among youth was due to preventable injury.(3) An American Academy of Pediatrics review of the injury prevention literature showed a positive benefit of prevention messages in 18 of 20 studies.(4) Although injury prevention programs historically have relied heavily on primary care providers, pediatric injury prevention and intervention programs that are initiated or occur during an emergency department (ED) visit are increasing in number, many with positive outcomes.(5–10) Adolescents who present to the ED for care may have elevated rates of risk behaviors compared to other teens, and ED-based injury prevention programs may provide access to adolescents who lack a primary care physician and who do not regularly attend school.(11)

Research from multiple disciplines suggests that injury is nonrandom and is best predicted by past experiences and behaviors.(12) Rates of injury among youth vary by demographics, including age, gender, and race; illicit weapon carrying; history of violent behavior or violence-related injury; and substance use.(13–16) Like injury, risk-taking behaviors also do not occur at random or in isolation, and tend to cluster in predictable ways (e.g., substance use, lack of seatbelt use, weapon carrying).(17) Most studies examining risk factors for injury have utilized national or school-based surveys; however, teens who present to the ED are likely to be from a different population of high-risk individuals who are not well-represented in school-based or general population samples.(18) There is increasing interest and effort focused on creating and evaluating injury prevention programs that originate during the ED visit. Understanding factors associated with past and current injury among teens presenting to the inner-city ED is essential so that future injury prevention efforts with this high-risk group seeking ED care can be more finely focused.

The ED visit itself, regardless of the teen’s reason for the visit, may provide a “teachable moment” for injury prevention. The majority of adolescent injury prevention in the ED has been focused on patients seeking care for an injury from a particular mechanism, such as violence interventions for assault-injured youth; alcohol-related interventions for adolescents seeking care for alcohol intoxication or an alcohol related injury; or drinking and driving interventions for patients involved in minor motor vehicle collisions.(8–10, 19) Focusing interventions only on those youth seeking care for acute injury or acute substance abuse may miss a large proportion of adolescents who would benefit from prevention activities. Understanding the risk factors for injury as well as the history of prior injury among all teens seeking care regardless of chief complaint is critical to developing successful ED-based injury prevention and intervention programs.

The overall purpose of this study was to examine past injury experiences among a large group of urban teens who were seeking ED care for a medical complaint or illness, by systematically surveying them over 12 months, with attention to risk factors commonly associated with injury. Specifically, the objectives of this study are to inform future ED-based injury prevention initiatives by determining the prevalence of injuries during the past year that were experienced by teens seeking care in an inner city ED and to identify factors (e.g., demographics, substance use, weapon carrying) associated with past-year injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Setting

This prospective, cross sectional, observational study took place in the ED at Hurley Medical Center, Flint, Michigan, a 540-bed teaching hospital and Level I Trauma Center, as the screening portion of a larger ongoing injury-related intervention study. Study procedures were approved and conducted in compliance with the guidelines of the University of Michigan and Hurley Medical Center Institutional Review Boards (IRB) for Human Subjects. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health for this study.

Population

Teens, ages 14–18 years, presenting to the ED for either medical illness or injury were eligible for this survey as part of a larger randomized, controlled trial of an ED-based brief intervention, and asked by research staff to participate. Patients were excluded if they were being treated for sexual assault, acute suicidal ideation, or were schizophrenic. Those patients who presented with an altered mental status precluding informed consent, or who had abnormal vital signs, also were not eligible for the survey. Patients presenting with acute intoxication were approached after their mental status cleared.

Study Protocol

Recruitment took place from 1:00 pm–11:00 pm (due to research assistant availability), seven days per week from September 2007 to September 2008, excluding major holidays. Consenting participants self-administered a 15-minute computerized survey on a laptop computer in treatment rooms (with audio via headphones to address literacy levels) and received a token $1.00 gift (e.g., notebook, pens). A research assistant (RA) was available to assist, if needed. Parental consent was obtained for youth under the age of 18 years. The RAs ensured that no one else was able to view the computer (including parents or friends) while each participant was taking the survey.

Measurements

Measures were all obtained via self-administered computerized survey using validated instruments. Demographic information using items selected from the National Study of Adolescent Health included age, sex, race/ethnicity, family receipt of public assistance, and current grades in school.(20)

Past-year injury

The Adolescent Injury Checklist was used to record injuries during the previous 12 months, whether the injury involved alcohol, and if medical care was required.(21) Sample questions include, "In the past 12 months, not including today, were you injured this way…By being in a physical fight with someone?…While riding in a car?" For the analysis, intentional injury was defined as an injury related to a physical fight, being physically attacked, or involvement in a weapon-related injury. Other injuries (sports, bike or skateboard, while riding in or driving a car, and falling) were classified as unintentional. Participants were allowed to report more than one injury in the past year.

Substance use

Frequency and quantity of drinking and heavy drinking of alcohol were assessed with three consumption items from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C).(22) Participants were asked to indicate how often they consumed alcohol in the past 12 months (ranging from “never” to “daily or almost daily”), and how often they consumed 5 or more drinks on one occasion (binge drinking). Participants were also asked to indicate how often they smoked cigarettes or marijuana in the past year.(23) All responses were collapsed into dichotomous variables representing “ever” or “never” in the past 12 months.

Weapon carrying

Two questions regarding weapon carrying were derived from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS).(24) The questions included: “In the past 12 months, how often have you: Carried a knife or razor? Carried a gun?" Responses were collected on a 7-point Likert scale.(25, 26) For the analysis, a single “yes” or “no” weapon carrying item was created.

Statistical Analysis

SAS proprietary software, release 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses. Analyses were conducted to identify: 1) the description of past-year injuries; and 2) factors associated with past-year injury history. Descriptive statistics (counts and percentages) were reported for type of past-year injury (skateboarding, driving a car, fight), if the youth was treated by a doctor or nurse for the injury, or if the injury involved alcohol. Bivariate associations between past-year injury, demographics, and risk behaviors were tested, then multinomial logistic regression was performed to determine independent predictors of past-year injury, with the no past-year injury group used as the reference group. For all bivariate analyses, counts, percentages, and p-values corresponding with chi-square tests of proportions were reported. For all regression analyses, adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals were reported. Alcohol use and binge drinking were highly correlated, therefore, binge drinking was retained in the final model (dropping alcohol use) as it has a stronger theoretically grounded association with injury risk. Multicolinearity diagnostics were calculated on all variables retained in the final regressions and there was no evidence of multicolinearity.

RESULTS

Recruitment and Overall Sample Description

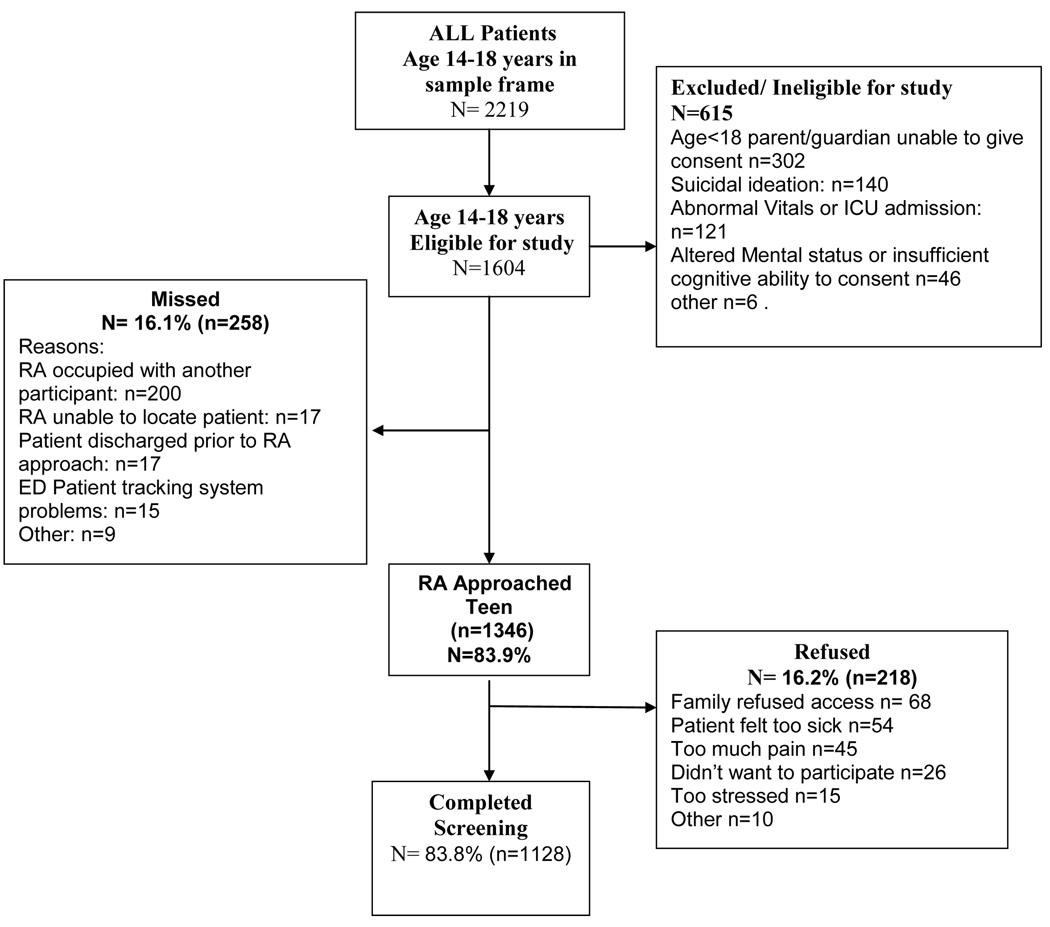

Among eligible patients who were approached, 83.8% (n=1128) completed the screening questionnaire and 16.2% (n=218) refused to participate (48% African American, 52% male) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study Flowchart - September 2007- September 2008

Of the total sample (n=1128), more than half were female (54.1%), more than half (58.0%) were African American, and 36.1% were Caucasian or Hispanic/Latino ethnicity, consistent with the city’s population (Table 1). The majority of the sample presented with a medical illness (58.6%), while 35.5% presented with unintentional injury and 5.9% with intentional injury. Comparisons between the screening sample and refusals indicated the groups were similar by gender (X2=2.75, p=.10), race (X2=3.24, p=.07), and chief complaint (medical, unintentional injury, intentional injury) (X2=2.18, p=.34). On average, participants were 16 years old (SD=1.5). More than half the sample (55.8%) reported that their families received public assistance. Approximately one-quarter of the participants reported past-year alcohol, cigarette, or marijuana use (28%, 26.6%, and 28.5%, respectively). Fourteen percent reported binge drinking. Nearly one-quarter reported past-year weapon carrying (23.5%). One-third of teens reported failing grades in school (mostly D’s or F’s).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Overall Population

| N=1128 | |

|---|---|

| Demographics and Risk Behaviors |

|

| n (%) | |

| Age (16 yrs and older) | 665 (59.0%) |

| African American | 654 (58.0%) |

| Hispanic/ Latino | 67(6.0%) |

| Male | 518 (46.9%) |

| Public assistance | 627 (55.8%) |

| Failing grades ( mostly D or F) |

364 (32.3%) |

| Alcohol use | 315 (28.0%) |

| Binge drinking | 162 (14.4%) |

| Cigarette use | 301 (26.6%) |

| Marijuana use | 416 (36.9%) |

| Weapon carrying | 265 (23.5%) |

Past-Year Injuries

Among the 1128 patients who participated in this study, 768 reported past-year injuries; 61.8% (n=475) reported an unintentional injury and 38.1% (n=293) reported an intentional injury (Table 2). Half (51.9%) of the teens who reported a past-year intentional injury were female. One-third of all youth seeking care reported a past-year sports-related injury (34.5%; 389/1128) or an injury from falling (34.4%; 388/1128); 16.5% reported an injury due to a physical fight (186/1128), and 8.2% (93/1128) noted a gun-related injury. Although many of the teens were not yet of driving age, 12.3% (139/1128) noted an injury related to driving or riding in a car. Nearly half of all the injuries reported (369/768, 48%) received medical attention. Car related injuries most often received medical attention for the injury across all injury types; violent injuries in any category had a larger proportion of respondents reporting alcohol involvement in the injury.

Table 2.

Prevalence and type of past-year injury (n=1128)

| Received medical attention for the injury |

Involved alcohol |

Received medical attention for the injury |

Involved alcohol |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Unintentional injury |

n=475† | n (%)‡ | n (%)‡ |

Intentional injury |

n=293† | n (%)‡ | n (%)‡ |

| Sports-related | 389 | 186 (47.8) | 3 (<1.0) | Physical fight |

186 | 49 (26.3) | 16 (8.6) |

| Falling | 388 | 151 (38.9) | 17 (4.4) | Physically attacked |

105 | 42 (40.0) | 9 (8.6) |

| Bike & skateboard |

159 | 27 (17.0) | 4 (2.5) | Gun- related |

93 | 17 (18.3) | 6 (6.5) |

| Cut | 85 | 31 (36.5) | 5 (5.9) | ||||

| Riding in a car | 70 | 37 (52.9) | 3 (4.3) | ||||

| Driving a car | 69 | 35 (50.7) | 2 (2.9) |

Participants may indicate more then one injury, therefore, the number of injuries total more than the number of participants.

Percentages indicate row percentages (e.g., of those with sports-related injuries, 186 [47.8%] received medical attention for the injury).

Factors Associated with Past-Year Injury

In bivariate analysis (Table 3), a significantly greater proportion of teens with a past-year history of intentional injury were male, reported substance use and weapon carrying compared to those with no past-year injury. Those with a past-year unintentional injury, when compared to those with no past-year injury, differed only with regard to demographics: they were significantly more likely to be male, and less likely to receive public assistance or to be African American compared to those with no past-year injury.

Table 3.

Bivariate analysis of demographics and risk behaviors by past-year injury (n=1128)

| Demographics and Risk Behaviors |

Past-year intentional injury n=293 (26.0%) |

Past-year unintentional injury n=475 (42.1%) |

No past-year injury n=360 (31.9%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age (16 yrs and older) | 175 (59.7) | 268 (56.4) | 222 (61.7) |

| African American | 182 (62.1) | 232 (48.8) *** | 240 (66.7) |

| Male | 141 (48.1)** | 249 (52.4)*** | 128 (35.6) |

| Public assistance | 171 (58.4) | 237 (49.9) * | 219 (60.8) |

| Alcohol use | 117 (39.9)*** | 124 (26.1) | 74 (20.6) |

| Binge drinking | 63 (21.5)*** | 65 (13.7) | 34 (9.4) |

| Cigarette use | 103 (35.2)*** | 113 (23.8) | 84 (23.3) |

| Marijuana use | 120 (41.0) *** | 113 (23.8) | 88 (24.4) |

| Weapon carrying | 108 (36.9)*** | 97 (20.4) | 60 (16.7) |

Reference for both past-year intentional injury and unintentional injury = no past-year njury

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

Multinomial logistic regression predicting past-year injury (unintentional or intentional vs. medical illness) was performed (Table 4). The overall model was significant (χ2 (18) = 114.2, p<.0001). Males (AOR=1.83, range 1.37–2.44) were more likely to report past-year unintentional injury, while African American youth (AOR=0.56, range 0.41–0.77) and those receiving public assistance (AOR=0.73, range 0.54–0.98) were less likely to report past-year unintentional injuries. Behavioral risk factors (binge drinking, marijuana use, weapon carrying) were not significantly different in the regression model between unintentional injury and no injury. In contrast, male gender (AOR=1.49, range 1.07–2.06), binge drinking (AOR=1.95, range 1.15–3.31), and weapon carrying (AOR=2.31, range 1.56–3.41) predicted past-year intentional injury.

Table 4.

Multinomial logistic regression comparing demographics and behavioral risk factors by past-year injury type (n=1128)

| Demographics and behavioral risk factors |

Past-year intentional injury n=293 (26.0%) |

Past-year unintentional injury n=475 (42.1%) |

|---|---|---|

| AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Age(16 yrs and older) | 0.76 (0.54–1.07) | 0.81 (0.60–1.09) |

| African American | 1.01 (0.70–1.44) | 0.56 (0.41–0.77)** |

| Male | 1.49 (1.07–2.06)* | 1.83 (1.37–2.44) *** |

| Public assistance | 0.87 (0.62–1.22) | 0.73 (0.54–0.98) * |

| Cigarette use | 1.17 (0.76–1.80) | 0.91 (0.61–1.35) |

| Binge drinking | 1.95 (1.15–3.31)* | 1.55 (0.92–2.58) |

| Marijuana use | 1.34 (0.88–2.05) | 0.90 (0.61–1.35) |

| Weapon carrying | 2.31 (1.56–3.41)*** | 1.24 (0.85–1.82) |

Reference for both models = no past-year injury (n=360)

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

DISCUSSION

The ED remains an underutilized venue for the prevention of injury among adolescents who may not hear these messages in other settings. Older adolescents are over-represented in ED visits relative to their proportion in the population, perhaps reflecting significant declines in visits to pediatricians in late adolescence, particularly by males.(27, 28) This study is novel in describing the prevalence of types of injuries experienced by a general sample of inner city adolescents who sought ED care, to inform future injury prevention initiatives. Although injury prevention programs historically have relied heavily on primary care providers, pediatric injury prevention and intervention programs that are initiated or occur during an ED visit are increasing in number, and may be particularly salient for underserved populations with limited access to primary care.(5–10) The majority of teens seeking ED care had a recent injury (68%), with almost half of the injuries requiring medical attention. Considering that many of these injuries were of a mechanism that has potential for serious injury (8.2% with a gun-related injury and 12.3% with an injury related to driving or riding in a car), the ED visit may be an opportunity for injury prevention efforts even if youth do not present to the ED seeking care for an injury.

Youth reporting past-year intentional injury were more likely to have a cluster of high-risk behaviors, including binge drinking and weapon carrying. These findings are consistent with other research that shows an association between substance use and risk of intentional injury. A recent meta-analysis of ED studies estimated an attributable risk of 43% for drinking prior to violence-related injuries.(29) Nearly half (49%) of adolescent drinkers are also involved in violent behaviors (e.g., physical fighting, weapon use), although not necessarily while they are under the influence of alcohol.(30) A variety of studies from non-ED samples indicate that violent behaviors and alcohol misuse are often associated with other problem behaviors, such as illicit drug use and delinquency during adolescence, and reflect the propensity for a large constellation of problem behaviors during adolescence.(31) Consistent with prior research, youth seeking ED care who reported weapon carrying in our study were also more likely to have had a intentional injury in the past year.(32)

The data from this study are in keeping with prior literature demonstrating a high rate of injury among males compared with females.(33, 34) Males have higher death rates than females, both for unintentional injury and violence.(35) Adolescent males are more likely to engage in risk-taking behaviors, including physical fights and weapon carrying, compared with their female peers.(36) In contrast, however, more than half (52%) the teens in this study who reported a past-year intentional injury were female. This is consistent with national data and other ED based studies that have found high rates of violent behavior and injury among females approaching that of their male peers.(34, 37)

In this study, being African American was not associated with past-year intentional injury. Other sources have shown that African Americans and Latinos are over-represented as both victims and offenders of violence, and violence-related mortality rates are higher among ethnic minorities than among non-minority groups.(38, 39) However, the association between race and intentional injury may be confounded by socioeconomic status, an effect perhaps not seen in this sample because it was fairly homogeneous with regard to income (56% reported receiving public assistance).(40) Caucasian youth had a higher risk of past-year unintentional injury. Other research has noted that Caucasian youth are at higher risk for sports and recreation-related injuries than African-American or Hispanic youth, and that higher socioeconomic status may also increase the risk of these injuries.(41) This pattern may reflect socioeconomic and socio-cultural differences, i.e., injuries largely represented in this sample such as biking and skateboarding require access to recreational space and equipment that may not be available to those living in less affluent neighborhoods, and might also reflect cultural preferences for recreation and entertainment. It is notable that even though 12% of the unintentional injuries in this study were related to driving, 46% of the sample had not yet reached the legal driving age.

Although more research is needed to develop and evaluate ED-based injury prevention programs, several prior ED-based initiatives have shown promise in taking the next step from screening youth with high risk behavior to successfully enrolling them in ED-based interventions.(5–10, 42) Among older adolescents (>16 years of age) presenting to the ED for alcohol-related reasons, brief interventions have been shown to be feasible and effective at changing alcohol-related injuries or problems.(10) Another study examined a computerized delivery of an alcohol prevention program for adolescents in the ED that showed promise among high risk older adolescents. Hospital- and ED-based violence interventions have largely focused on youth with assault related injuries, actively linking them to outpatient resources.(7–9, 16)

The data presented here highlight the high rates of past injury, including assault related injury, among a general sample of youth seeking ED care. The ED visit is an opportunity to interact with high risk youth who have engaged in or considered risky behaviors, including substance use, drinking and driving, or riding with an impaired driver.

Limitations

This study was limited by its cross-sectional design, and the self-reported nature of the data. Recent reviews of studies of adolescents and young adults, however, have concluded that reliability and validity of self-reported alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use is high, and adolescents and young adults are most likely to report drug use using computerized surveys and when privacy and confidentiality are assured.(43–45) As the survey was limited to the hours of 1:00–11:00 pm, the characteristics of youth evaluated during the overnight hours are unknown. Finally, the strength of this study is its focus on an inner-city ED, which may be an important location for interventions to prevent violence, and the findings may not generalize to other suburban or rural settings.

CONCLUSIONS

To our knowledge, no prior studies have examined the rates and associated risk factors of past injury among a large, systematically sampled group of youth seeking care in an inner-city ED over one full year. Understanding the recent injury experience of teens in inner city EDs will inform future intervention programs. Universal screening of all teens seeking care in the inner-city ED may be warranted based on high rates of risky behavior and past-year injuries. More research into the most feasible mechanisms to deliver injury screening and interventions in the ED is warranted, including research involving additional non-ED staff. The feasibility of screening and intervention delivery is critical given the importance of the setting for contact with high risk teens, as well as the common resource constraints of overburdened ED health care staff. For teens with a past-year injury, identifying those who binge drink or carry weapons may help to identify those youth who would benefit the most from injury prevention programs, since their recent injury-related experience may increase the saliency of prevention messages.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a grant (#14889) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). We would like to thank project staff Bianca Burch, Yvonne Madden, Tiffany Phelps, Carrie Smolenski, and Annette Solomon for their work on the project; also, we would like to thank Pat Bergeron for administrative assistance and Linping Duan for statistical support. Finally, special thanks are owed to the patients and medical staff at Hurley Medical Center for their support of this project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]. Ten leading causes of death. United States 2005. [cited 2008 March 28];2005 2005, Available from: www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars.

- 2.Christoffel T, Scavo Gallagher S. Gaitherburg, MD: Aspen Publishers; 1999. Injury Prevention and Public Health: Practical Knowledge, Skills, and Strategies. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Adolescent Health Information Center (NAHIC) 2006 fact sheet on mortality: Adolescents and young adults. [cited 2008 March 28]; Available from: http://nahic.ucsf.edu/download.php?f=/downloads/UnintInjury.pdf.

- 4.Bass JL, et al. Childhood injury prevention counseling in primary care settings: a critical review of the literature. Pediatrics. 1993;92(4):544–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Posner JC, et al. A randomized, clinical trial of a home safety intervention based in an emergency department setting. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6):1603–1608. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston BD, et al. Behavior change counseling in the emergency department to reduce injury risk: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2002;110(2 Pt 1):267–274. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maio RF, et al. Adolescent injury in the emergency department: opportunity for alcohol interventions? Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35(3):252–257. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(00)70076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zun LS, Downey L, Rosen J. The effectiveness of an ED-based violence prevention program. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24(1):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng TL, et al. Randomized trial of a case management program for assault-injured youth. Ped Emerg Care. 2008;24(3):130–136. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181666f72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monti PM, et al. Brief intervention for harm reduction with alcohol-positive older adolescents in a hospital emergency department. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(6):989–994. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson KM, Klein JD. Adolescents who use the emergency department as their usual source of care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(4):361–365. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallagher CA. Injury recurrence among untreated and medically treated victims of violence in the USA. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(3):627–635. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergen G, et al. Hyatsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. Injury in the United States: 2007 chartbook. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammig BJ, Dahlberg LL, Swahn MH. Predictors of injury from fighting among adolescent males. Inj Prev. 2001;7(4):312–315. doi: 10.1136/ip.7.4.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sege R, et al. Ten years after: examination of adolescent screening questions that predict future violence-related injury. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24(6):395–402. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng TL, et al. Adolescent assault injury: risk and protective factors and locations of contact for intervention. Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):931–938. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jessor R. Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action. J Adolesc Health. 1991;12(8):597–605. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(91)90007-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowenstein SR, et al. Behavioral risk factors in emergency department patients: a multisite survey. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5(8):781–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mello MJ, et al. Emergency department brief motivational interventions for alcohol with motor vehicle crash patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(6):620–625. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris K, et al. The national longitudinal study of adolescent health: Research design [WWW document] [cited May 21 2008];2003 Available from: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design.

- 21.Jelalian E, et al. Adolescent motor vehicle crashes: the relationship between behavioral factors and self-reported injury. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27(2):84–93. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bush K, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston LD, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2006. Volume 1: Secondary school students. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2007:699.

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Survey. [cited 2007 November 4];2005b Available from: www.cdc.gov/yrbss.

- 25.Brener ND, et al. Reliability of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:575–580. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brener ND, et al. Reliability of the 1999 youth risk behavior survey questionnaire. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(4):336–342. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ziv A, Boulet JR, Slap GB. Emergency department utilization by adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics. 1998;101(6):987–994. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.6.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marcell AV, et al. Male adolescent use of health care services: where are the boys? J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00319-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y, Bond J. Attributable risk of injury associated with alcohol use: cross-national data from the emergency room collaborative alcohol analysis project. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(2):266–272. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.031179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swahn MH, et al. Alcohol-consumption behaviors and risk for physical fighting and injuries among adolescent drinkers. Addict Behav. 2004;29(5):959–963. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donovan JE, Jessor R, Costa FM. Syndrome of problem behavior in adolescence: a replication. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(5):762–765. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.5.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pickett W, et al. Cross-national study of fighting and weapon carrying as determinants of adolescent injury. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):e855–e863. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moskowitz H, et al. Serious injuries and deaths of adolescent girls resulting from interpersonal violence: characteristics and trends from the United States, 1989–1998. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(8):903–908. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.8.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mollen CJ, et al. Characterization of nonfatal events and injuries resulting from youth violence in patients presenting to an emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(6):379–384. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000101577.65509.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Adolescent Health Information Center (NAHIC) 2007 fact sheet on violence: Adolescents and young adults. [cited 2008 March 28]; Available from: http://nahic.ucsf.edu//downloads/Violence.pdf.

- 36.Jelalian E, et al. Risk taking, reported injury, and perception of future injury among adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 1997;22(4):513–531. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.U.S. Department of Justice. Rockville, MD: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2000. Juvenile Arrests 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 38.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Youth Violence: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2001

- 39.National Adolescent Health Information Center (NAHIC) 2007 fact sheet on unintentional Injury: Adolescents and young adults. [cited 2008 March 28]; Available from: http://nahic.ucsf.edu/download.php?f=/downloads/UnintInjury.pdf.

- 40.Rich JA, Sullivan LM. Correlates of violent assault among young male primary care patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2001;12(1):103–112. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ni H, Barnes P, Hardy AM. Recreational injury and its relation to socioeconomic status among school aged children in the US. Inj Prev. 2002;8(1):60–65. doi: 10.1136/ip.8.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cunningham R, et al. Acute violent injury, violence history, and substance use among an injured ED population. Acad Emerg Med. In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dennis M, et al. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) experiment: rationale, study design and analysis plans. Addiction. 2002;97 Suppl 1:16–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.97.s01.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brener ND, Billy JO, Grady WR. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: evidence from the scientific literature. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(6):436–457. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harrison LD, et al. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2007. Comparing drug testing and self-report of drug use among youths and young adults in the general population. [Google Scholar]