SUMMARY

Bacteria can respond to adverse environmental conditions by drastically reducing or even ceasing metabolic activity. They must then determine that conditions have improved before exiting dormancy, and one indication of such a change is the growth of other bacteria in the local environment. Growing bacteria release muropeptide fragments of the cell wall into the extracellular milieu, and we report here that these muropeptides are potent germinants of dormant Bacillus subtilis spores. The ability of a muropeptide to act as a germinant is determined by the identity of a single amino acid. A well-conserved, eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr membrane kinase containing an extracellular domain capable of binding peptidoglycan is necessary for this response, and a small molecule that stimulates related eukaryotic kinases is sufficient to induce germination. Another small molecule, staurosporine, that inhibits related eukaryotic kinases blocks muropeptide-dependent germination. Thus, in contrast to traditional antimicrobials that inhibit metabolically active cells, staurosporine acts by blocking germination of dormant spores.

INTRODUCTION

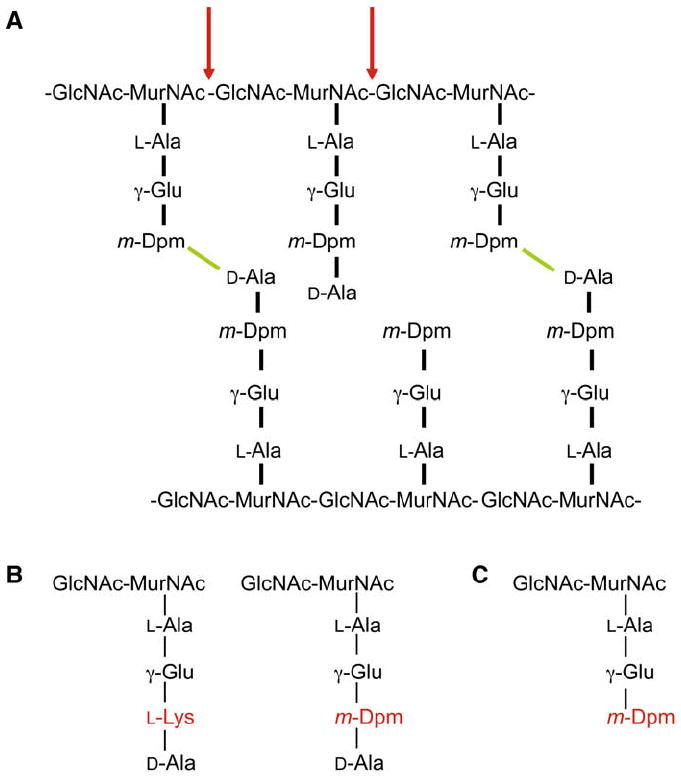

Bacterial shape and cellular resistance to cytoplasmic turgor pressure are determined by peptidoglycan (PG), a polymer of repeated subunits of an N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc) peptide monomer that surrounds the cytoplasmic membrane (Figure 1A). Covalent interactions between the stem peptides arising from separate chains typically crosslink the GlcNAc-MurNAc polymers, although in some organisms this crossbridge is composed of one or more amino acids. Most Gram-positive bacteria contain an l-lysine residue at the third position of the stem peptide (Figure 1B, left), whereas Gram-negative bacteria and most endospore formers have an m-Dpm (meso-diaminopimelic acid) residue in this position (Figure 1B, right).

Figure 1. Peptidoglycan Structure.

(A) B. subtilis peptidoglycan is composed of chains of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc) attached to stem peptides. Bonds (green) between m-Dpm and D-Ala residues arising from separate chains crosslink the GlcNAc-MurNAc polymers. The vast majority of the D-Ala residues that are not in crosslinks (>95%) are removed, leaving the tripeptides, and only 40% of the peptides are cross-linked. Mutanolysin (red) hydrolyzes the β-1,4 bond between the MurNAc and GlcNAc sugars.

(B) Most Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., S. aureus) contain an L-Lys residue at the 3rd position of the stem peptide (left). Gram-negative bacteria and most spore formers (except B. sphaericus) have an m-Dpm residue in this position (right).

(C) Structure of disaccharide tripeptide.

Peptidoglycan fragments serve as signals in a range of host-microbe interactions including B. pertussis infection and V. fischeri-squid symbiosis (Cloud-Hansen et al., 2006). They also stimulate the innate immune response (Hasegawa et al., 2006) by binding to host proteins like Nod1 (Girardin et al., 2003). Peptidoglycan fragments are generated by growing cells as peptidoglycan hydrolases and amidases partially digest the mature peptidoglycan to allow insertion of additional peptidoglycan monomers (Doyle et al., 1988). While Gram-negative bacteria can efficiently recycle the resulting muropeptides, the lack of a similar recycling system in Gram-positive bacteria results in the release of large quantities of peptidoglycan fragments into the extracellular milieu by growing cells (Doyle et al., 1988; Mauck et al., 1971).

Dormant bacteria must monitor nutrient availability so that they can reinitiate metabolism when conditions become favorable. This could be accomplished by determining changes in the levels of individual nutrients. Alternatively, the growth of other bacteria in the environment would also indicate the presence of favorable conditions. Since growing bacteria release muropeptides into the environment, these molecules could serve as an intercellular growth signal to dormant bacteria.

Some Gram-positive species produce dormant spores under conditions of nutritional limitation. These cells are resistant to harsh environmental conditions and can survive in a dormant state for years (Nicholson et al., 2000). Spores exit from dormancy via the process of germination that is triggered by specific molecules known as germinants. Most spore-forming bacteria encode several germination receptors; for example, the B. subtilis GerAA/AB/AC proteins are necessary for germination in response to L-alanine. GerAA and GerAB are integral membrane proteins and GerAC is a putative lipoprotein. GerAA and GerAC, and GerBA, a GerAA homolog, are located in the inner membrane of the spore (Hudson et al., 2001; Paidhungat and Setlow, 2001) where they are positioned to detect germinants that can pass through the outer layers of the spore. The precise chemical nature of germinants varies according to the species, and although they are typically nutrients, these molecules are not metabolized. The amino acid L-alanine or a mixture of asparagine, glucose, fructose, and potassium ions germinates B. subtilis spores, whereas L-proline germinates B. megaterium spores and purine ribonucleosides and amino acids act as co-germinants for B. anthracis spores (Setlow, 2003).

High concentrations of nutrient germinants would be consistent with the ability of the environment to support the growth of germinated spores. However, a more integrated determination of this ability is the growth of other microbes in the environment, and this growth would be indicated by the presence of released muropeptides. How might dormant spores recognize these muropeptides? One protein sequence hypothesized to bind peptidoglycan is the PASTA (“penicillin and Ser/Thr kinase associated”) repeat found in the extracellular domain of membrane-associated Ser/Thr kinases as well as in some proteins that catalyze the transpeptidation reaction in cell wall synthesis. The PASTA domain is a small (~55 aa) globular fold consisting of 3 β sheets and an α helix, with a loop region of variable length between the first and second β strands (Yeats et al., 2002). While the presence of PASTA domains in proteins that interact with peptidoglycan suggests that these domains may mediate this interaction, the binding of PASTA domains to peptidoglycan has not been demonstrated.

The cytoplasmic kinase domain of M. tuberculosis PknB, the essential PASTA-domain-containing Ser/Thr kinase, is structurally homologous to eukaryotic Ser/Thr kinases (Young et al., 2003). Consistent with this homology, PknB phosphorylates several proteins, including a transcriptional activator (Sharma et al., 2006) and a cell division protein (Dasgupta et al., 2006). The closely related B. subtilis PASTA-domain-containing Ser/Thr kinase, PrkC, phosphorylates elongation factor G (EF-G) both in vivo and in vitro. EF-G is an essential ribosomal GTPase involved in mRNA and tRNA translocation (Gaidenko et al., 2002), and although the activity of its eukaryotic homolog, eEF-2 (Ryazanov et al., 1988), is regulated by phosphorylation, similar data are not available for EF-G. While PrkC is not essential, ΔprkC strains have decreased viability (~1 log) following incubation in stationary phase for >24 hr (Gaidenko et al., 2002) and are moderately defective for sporulation (Madec et al., 2002).

Here we show that muropeptides, purified peptidoglycan or supernatants derived from cultures of growing cells, are potent germinants of dormant B. subtilis spores. Diverse bacteria can serve as the source of these molecules, but the identity of a single amino acid residue in the peptidoglycan stem peptide determines its ability to induce germination. PrkC is necessary for this germination response, and several small molecules known to affect the activity of related eukaryotic kinases either stimulate or inhibit germination.

RESULTS

Cell-free Supernatant Causes B. subtilis Spores to Germinate

Dormant bacteria must continuously monitor conditions so that they can reinitiate metabolism when conditions become favorable. The growth of other bacteria in the local environment would reflect such changes, and this growth could be assayed by detecting released metabolic byproducts. These molecules would then serve as a signal for dormant cells that conditions conducive to growth are present. For example, dormant spores would be germinated by supernatants derived from growing bacterial cultures.

We tested this possibility by growing B. subtilis and removing the cells from the supernatant by repeated filtration. Germination was assayed by measuring loss of heat resistance because dormant, but not germinated, spores are resistant to wet heat. Incubation of cell-free supernatants from B. subtilis cultures induced germination of dormant spores (Figure 2A, squares). This germination caused phase bright spores to become phase dark (Figure S1 available online) and occurred with similar kinetics as seen with nutrient germination (Figure S2). However, cell-free supernatants from the Gram-positive bacterium S. aureus did not induce germination, indicating that the stimulatory component was not generated by this species (Figure 2A, diamonds). Supernatants from E. coli cultures were also effective, albeit with decreased potency (Figure 2A, circles). The reduced effectiveness of E. coli supernatants likely results from the presence of the outer membrane that acts as a permeability barrier for hydrophilic compounds in the periplasm (Beveridge, 1999) and therefore inhibits the release of molecules from the cell. However, the ability of cell-free supernatants derived from a Gram-positive and a Gram-negative species to induce germination suggests that the molecule(s) responsible are likely to be released by a phylogenetically broad range of bacteria. Finally, since supernatants isolated from cells transferred to non-growth medium failed to efficiently germinate spores (Figure S3), these molecules are likely to be produced only by growing cells.

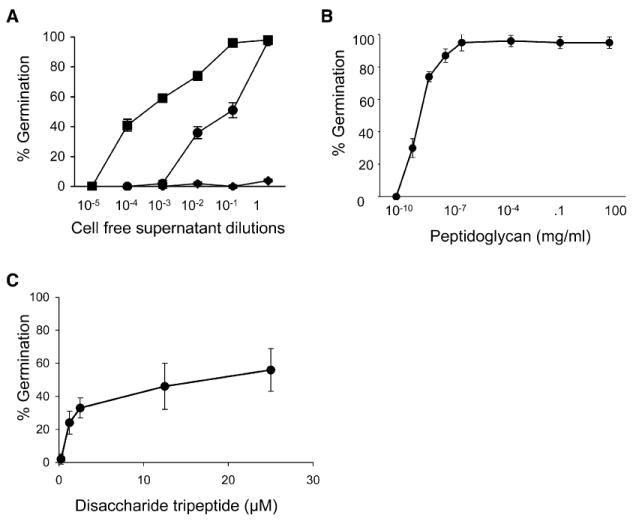

Figure 2. Peptidoglycan Germinates Bacterial Spores.

(A) Cell-free supernatant prepared from growing B. subtilis PY79 (squares), E. coli DH5α (circles), or S. aureus Newman (diamonds) at a range of dilutions incubated with B. subtilis spores for 60 min.

(B) B. subtilis mutanolysin-digested peptidoglycan at a range of concentrations incubated with wild-type B. subtilis spores for 60 min.

(C) Disaccharide tripeptide at a range of concentrations incubated with wild-type B. subtilis spores for 60 min. Error bars represent standard deviation (SD) for triplicate samples.

Peptidoglycan Causes B. subtilis Spores to Germinate

The increased spore germination induced by B. subtilis cell-free supernatant as compared to E. coli is consistent with the larger release of peptidoglycan fragments by Gram-positive as compared to Gram-negative bacteria (Goodell and Schwarz, 1985). Thus, peptidoglycan fragments may act as a spore germinant. To examine this possibility, we purified peptidoglycan from growing B. subtilis cells and digested it into muropeptides with mutanolysin, an enzyme that hydrolyzes the β-1,4 bond between the MurNAc and GlcNAc sugars (red arrow, Figure 1A). Concentrations of peptidoglycan as low as ~0.1 pg/ml induced germination (Figure 2B), indicating that spores detected one or more peptidoglycan fragments. This amount of peptidoglycan corresponds to <1 B. subtilis cell based on our isolation of ~100 mg peptidoglycan from a 100 ml B. subtilis culture grown to an optical density (OD) of 1.2. B. subtilis peptidoglycan also germinated spores generated by other Bacilli including B. anthracis and B. megaterium (data not shown), indicating that the peptidoglycan germination signal is not genus specific.

Bacterial peptidoglycan is often covalently associated with proteins and the anionic polymer teichoic acid. However, treatment of peptidoglycan with the proteases pronase and trypsin did not reduce its ability to act as a germinant (data not shown). In addition, peptidoglycan generated from a B. subtilis tagO mutant that is unable to synthesize teichoic acids (D’Elia et al., 2006) is similarly active as a germinant (data not shown). Thus, peptidoglycan fragments themselves are most likely to be the spore germinant. Further, peptidoglycan isolated from the spore cortex fails to efficiently function as a spore germinant (Figure S4), indicating that only peptidoglycan released by or isolated from vegetative cells functions as a germinant.

Muropeptides Act as Spore Germinants

The ability of both purified mutanolysin-digested peptidoglycan and cell-free supernatant to germinate spores suggested that muropeptides present in both preparations were responsible. To examine this possibility, we used high-performance liquid chromatography to separatemutanolysin-digested B. subtilis peptidoglycan into its muropeptide constituents. Incubation of disaccharide tripeptides with dormant B. subtilis spores at concentrations as low as 1 μM (Figure 2C) led to germination. In addition, disaccharide tetrapeptides were equivalently effective as germinants (data not shown). However, the concentrations of purified disaccharide tripeptides required for a germination response (μM) are higher than the concentration of muropeptides resulting from directly digesting peptidoglycan with mutanolysin (pM). One likely explanation for this difference is the substitution of muramic acid to muramitol due to a reduction step before HPLC purification. Further, both muramyl dipeptide (1 mM, data not shown) and an Ala-D-γ-Glu-Dpm tripeptide (500 μM, data not shown) failed to induce germination, suggesting that both the disaccharide and the third residue in the stem peptide play an important role. Thus, a disaccharide tripeptide appears to be the minimal chemical unit sufficient to germinate spores. Interestingly, a similar requirement is observed with a human peptidoglycan recognition protein heterodimer that binds tracheal cytotoxin where the disaccharide bridges the two proteins (Chang et al., 2006; Lim et al., 2006).

Muropeptide Specificity

The ability of both supernatants derived from cultures of growing B. subtilis and E. coli, but not S. aureus, to induce germination (Figure 2A) could be the result of the presence of an m-Dpm residue in the third position of their stem peptides (Figure 1B, right). S. aureus, like most Gram-positive bacteria, has an L-Lys at that position (Schleifer and Kandler, 1972), so the identity (m-Dpm versus L-Lys) of the third residue in the stem peptide could play an important role in recognition of peptidoglycan by spores. We examined this possibility by purifying peptidoglycan from a number of Gram-positive species that contain different amino acids at the third position of the stem peptide and assaying their ability to induce germination. Consistent with our prediction, only peptidoglycan containing m-Dpm at the third position acted as a germinant (Table 1). Peptidoglycan derived from the spore-former Bacillus sphaericus that, in contrast to all other Bacilli, contains an L-Lys at this position (Hungerer and Tipper, 1969) did not induce germination, highlighting the importance of this residue. Both the mammalian Nod1 protein selectively binds peptidoglycan fragments containing m-Dpm (Girardin et al., 2003) and the human peptidoglycan recognition protein heterodimer binds tracheal cytotoxin where the m-Dpm residue is the primary specificity determinant (Chang et al., 2006; Lim et al., 2006). Thus, the identity of the amino acid in the third position of the stem peptide is critical for the recognition of peptidoglycan by phylogenetically diverse proteins.

Table 1.

Role of Third Residue of Stem Peptide in Germination

| Species | Peptide | Germination |

|---|---|---|

| Bacillus subtilis | m-Dpm | + (85% ± 6) |

| Bacillus anthracis | m-Dpm | + (65% ± 8) |

| Bacillus megaterium | m-Dpm | + (57% ± 4) |

| Bacillus sphaericus | L-Lys | − (6% ± 5) |

| Clostridium acetobutylicum | m-Dpm | + (72% ± 8) |

| Listeria monocytogenes | m-Dpm | + (67% ± 3) |

| Streptomyces coelicolor | L,L-Dpm | + (77% ± 3) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | L-Lys | − (10% ± 4) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | L-Lys | − (5% ± 4) |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | L-Lys | − (8% ± 6) |

| Lactobacillus lactis | L-Lys | − (3% ± 2) |

Peptidoglycan isolated from different Gram-positive bacteria was incubated at concentrations of 100 mg/ml and 100 ng/ml with wild-type B. subtilis spores for 60 min. The presence of an L-Lys or an m-Dpm residue in the third position of the stem peptides is indicated: (+) >50% of the spores were heat sensitive in the presence of both concentrations of peptidoglycan; (−) no increase in heat sensitivity was observed in the presence of peptidoglycan.

Muropeptides Are Recognized by a Novel Germination Pathway

Nutrient germinants are detected by germination receptors located in the spore membrane. Since peptidoglycan fragments still germinated spores lacking all five previously identified germination receptors (Paidhungat and Setlow, 2000), these receptors were not involved in this response (Figure S1). Therefore, to identify the relevant receptor for peptidoglycan fragments during germination, we examined bacterial membrane proteins known or hypothesized to bind peptidoglycan. Diverse bacteria, including all known spore-forming bacteria, have at least one eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr membrane kinase containing multiple PASTA repeats in their extracellular domains (Figure 3A); these repeats have been hypothesized to recognize the peptidoglycan stem peptide (Jones and Dyson, 2006; Yeats et al., 2002). We therefore asked whether the B. subtilis member of this family, PrkCBs, is involved in peptidoglycan-dependent spore germination. Mutant spores lacking PrkCBs (ΔprkC) failed to germinate in the presence of peptidoglycan fragments or purified disaccharide tripeptides (Figure 3B) and tetra-peptides (data not shown). Thus, PrkCBs is required for the germination response of spores exposed to peptidoglycan. ΔprkC spores still responded to the nutrient germinant L-alanine (Figure 3B) and to the chemical germinant Ca2+-dipicolinic acid (Figure S5), indicating that the spores were still capable of germinating and that PrkCBs is not involved in nutrient or chemical germination.

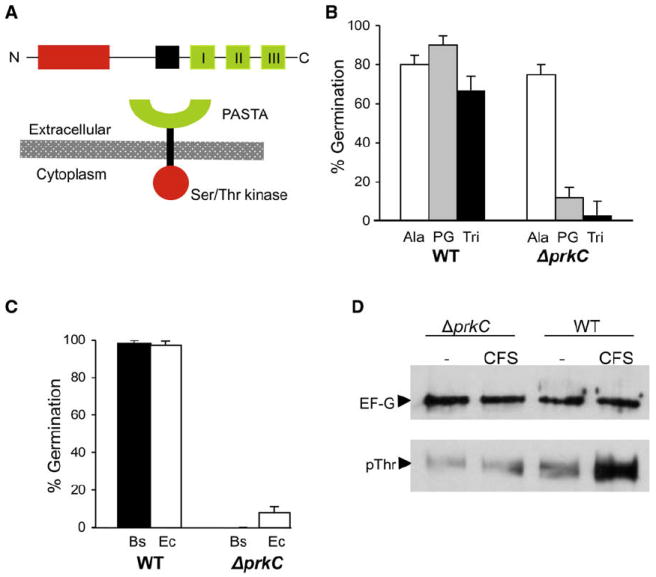

Figure 3. Peptidoglycan-Dependent Germination Uses a Novel Signal Transduction Pathway.

(A) PrkC consists of an N-terminal kinase domain (red), a membrane-spanning sequence (black), and three PASTA repeats (green) in the extracellular domain.

(B) Wild-type or ΔprkC spores incubated with L-alanine (1 mM), B. subtilis peptidoglycan (100 ng/ml), or B. subtilis disaccharide tripeptide (“Tri”; 10 μM) for 60 min.

(C) Wild-type or ΔprkC spores incubated with undiluted cell-free supernatant prepared from log-phase B. subtilis (Bs) or E. coli DH5α (Ec) for 60 min.

(D) Protein lysates from B. subtilis ΔprkC or wild-type spores incubated with buffer alone (–) or with B. subtilis cell-free supernatant (CFS; 10−3 dilution) for 60 min were immunoprecipitated with α-EF-G antibodies and subjected to western blotting with either α-EF-G or α-phosphothreonine antibodies.

Error bars represent SD for triplicate samples.

Since growing cells release peptidoglycan fragments into the extracellular milieu, germination by cell-free supernatant should also require PrkCBs. In support of this hypothesis, incubation of ΔprkCBs spores with cell-free supernatant derived from either B. subtilis or E. coli cultures (Figure 3C) did not result in germination. Although the identity of the component(s) in the supernatants necessary for germination is not known, the requirement for PrkCBs for germination in response to muropeptides suggests that these are likely to be the active molecules.

Finally, we tested the requirement for PrkC in another spore former by constructing a deletion of the B. anthracis prkC homolog. Spores carrying this mutation were similarly blocked in the germination response to peptidoglycan (Figure S6). Thus, the role of PrkC in germination is conserved in at least two spore-forming bacterial species.

PrkC Phosphorylates EF-G during Germination

During vegetative growth of B. subtilis, phosphorylation of EF-G, an essential ribosomal GTPase, is reduced in a strain lacking PrkC. In addition, purified kinase domain of PrkC phosphorylates EF-G in vitro on at least one threonine (Gaidenko et al., 2002). We therefore asked whether EF-G phosphorylation also occurs during PrkC-dependent germination. We generated lysates from wild-type and ΔprkC spores after incubation with cell-free supernatant for 60 min to stimulate germination and immunoprecipitated EF-G using polyclonal antibodies raised against E. coli EF-G (kind gift of W. Wintermeyer). When we probed these immunoprecipitated fractions with an anti-phosphothreonine antibody (Zymed), we observed that EF-G (as identified by probing the same fractions with the α-EF-G) phosphorylation increased following exposure to cell-free supernatant in wild-type spores (Figure 3D). In contrast, no change in phosphorylation was observed in spores lacking PrkC.

As a confirmation of the kinase activity of PrkC during germination, we generated a FLAG-tagged point mutant (K40A) of PrkC since that residue was identified as necessary for PrkC phosphorylation (Madec et al., 2002). Consistent with the expected effect of this mutation, this mutant PrkC did not support germination in response to PG (Figure S7) even though it was expressed and localized properly to the spore inner membrane (Figure S8), whereas a FLAG-tagged version of the wild-type protein did complement a ΔprkC mutation. Thus, PrkC appears to phosphorylate EF-G during germination,and this modification is likely necessary for germination in response to PG.

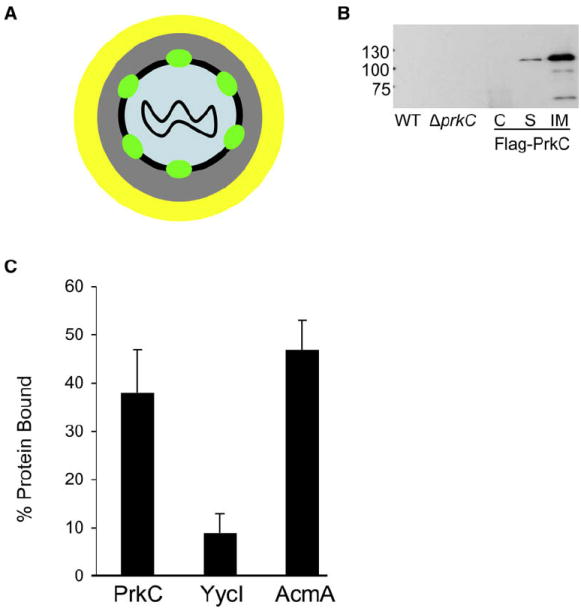

PrkC Localizes to the Spore Inner Membrane

The inability of ΔprkCBs spores to germinate in response to muropeptides suggested that PrkCBs is located either on the spore surface or in the spore interior. The presence of a hydrophobic stretch between the cytoplasmic kinase and extracellular PASTA domains as well as the association of PrkCBs with the cytoplasmic membrane in vegetative cells (Madec et al., 2002) suggest that PrkCBs is associated with the spore membrane, located below the spore coat (Figure 4A). To test the critical hypothesis that PrkCBs is membrane associated in the spore and therefore strategically positioned to sense extracellular peptidoglycan, we performed subcellular fractionation of spores expressing an epitope-tagged PrkC protein. Upon removal of the spore coat and outer membrane, we observed that a FLAG-PrkCBs fusion protein, which complements a ΔprkC mutation for peptidoglycan-dependent germination (Figure S7), was found in the inner membrane fraction of the spore (Figure 4B) similar to proteins involved in nutrient germination (Hudson et al., 2001; Paidhungat and Setlow, 2001).These decoated spores still responded to PG as a germinant (data not shown). Spores expressing either free GFP under control of a forespore-specific promoter or a fusion of GFP to a coat protein exhibited expected patterns of fractionation (Figure S8).

Figure 4. Localization and Peptidoglycan Binding of PrkC.

(A) Schematic of PrkC localization. The DNA is located in the core (blue) and is surrounded by the cortex (gray) and the coat (yellow). PrkC (green) is associated with inner membrane (black) of the spore.

(B) Lysates of wild-type (PY79), ΔprkC (PB705), and ΔprkC amyE::Pspac-FLAG-prkCBs (JDB2226) spores were electrophoresed using 8% SDS-PAGE, and blots were probed with anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma). Shown are whole-cell lysate from wild-type spores (WT); whole-cell lysate from ΔprkC spores (ΔprkC); coat fraction from JDB2226 (C); soluble S100 fraction from JDB2226 (S); insoluble P100 fraction from JDB2226 (IM).

(C) Fifty micrograms of His-tagged extracellular domains of PrkC, YycI, or AcmA were incubated with ~5 mg purified cell wall peptidoglycan. Centrifugation was used to separate protein bound to insoluble PG from unbound protein. Bound protein was eluted by subjecting insoluble fraction to 2% SDS. Fractions containing unbound protein and protein remaining bound to insoluble PG were subjected to 8% SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining and protein bands were quantified using Image J (NIH). The total protein that was incubated was normalized to 100% for unbound + bound and relative bound protein levels were calculated.

Error bars represent SD for triplicate samples.

Since molecules >2–8 kDa are unable to cross the spore coat (Driks, 1999), peptidogylcan fragments that interact with PrkC proteins located in the spore inner membrane below the coat (Figure 4A) must not exceed this size. The observed ability of disaccharide tri- and tetrapeptide fragments (868.9 Da and 940.0 Da, respectively) to germinate spores is consistent with this requirement.

Binding of Peptidoglycan by PrkC

The presence of the hypothesized peptidoglycan-binding PASTA repeats in the PrkC extracellular domain suggested that PrkC functions by binding peptidoglycan. We tested this possibility by expressing and purifying a His-tagged protein (His6-PASTABs) consisting of the entire extracellular domain of PrkC that contains three PASTA repeats. Following previous characterization of bacterial proteins that bind peptidoglycan (Eckert et al., 2006; Steen et al., 2003), His6-PASTABs was incubated with purified B. subtilis peptidoglycan and the mixture centrifuged. In this assay, bound protein pellet with the insoluble peptidoglycan molecules and unbound proteins remained in the supernatant. Under these conditions, His6-PASTABs remained soluble in the absence of added peptidoglycan (data not shown). The fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and the differences in the protein amounts as revealed by Coomassie staining were quantified (Figure 4C). Approximately 40% of the total protein was associated with the insoluble fraction, indicating that a substantial fraction of His6-PASTABs bound to peptidoglycan under the assay condition. As a control, we expressed and purified the His-tagged extracellular domain of YycI, a membrane-associated histidine kinase from B. subtilis (Santelli et al., 2007). Consistent with its lack of PASTA domains, only ~5% of the total protein was found in the insoluble fraction after incubation of this fragment with purified B. subtilis peptidoglycan. As a second control, we examined His6-AcmA, an L. lactis protein that binds peptidoglycan, in the assay, and like His6-PASTABs, approximately 40%–45% protein remained associated to PG (Figure 4C). Thus, the PASTA-containing extracellular C-terminal domain of PrkCBs binds peptidoglycan, consistent with the model that PrkCBs directly binds to muropeptides during germination.

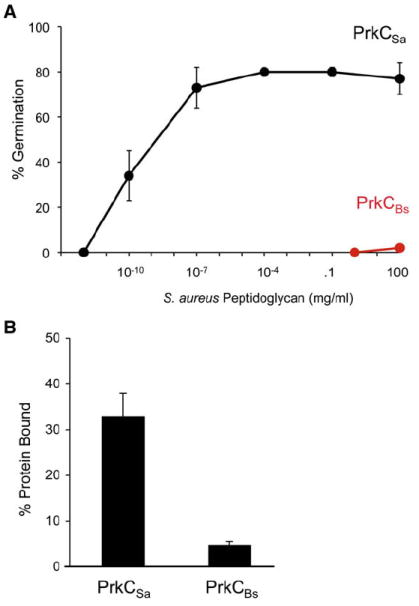

Specificity of PrkC

Peptidoglycan containing an L-Lys at the third position of the stem peptide does not germinate B. subtilis spores, whereas peptidoglycan containing an m-Dpm at this position does act as a germinant (Table 1). Since PrkC is necessary for this germination and the PrkC extracellular domain binds peptidoglycan (Figure 4C), this specificity may originate in PrkC. Thus, a PrkC homolog from a bacterium containing an L-Lys residue should respond to L-Lys containing peptidoglycan. We tested this possibility by substituting the PrkC homolog from the L-Lys-containing species S. aureus (PrkCSa) for PrkCBs and determining whether spores expressing this heterologous protein germinated in response to L-Lys containing peptidoglycan.We amplified the gene encoding PrkCSa from the S. aureus chromosome and placed it under inducible control in the chromosome of a B. subtilis ΔprkCBs strain.

Transgenic PrkCSa expressing spores germinated in response to L-Lys containing S. aureus peptidoglycan (Figure 5A, black) whereas wild-type PrkCBs-expressing spores did not germinate (Figure 5A, red). Thus, the source of PrkC determined its ability to respond to L-Lys containing peptidoglycan since PrkCBs responds to B. subtilis peptidoglycan (Figure 3B). In addition, spores expressing PrkCSa germinated in response to B. subtilis peptidoglycan (data not shown), indicating that PrkCSa responds to both L-Lys and m-Dpm containing peptidoglycan. As a further test of this change in specificity, we incubated PrkCSa-expressing spores with S. aureus cell-free supernatant that does not germinate wild-type B. subtilis spores. Consistent with the previous observations regarding germination in response to S. aureus peptidoglycan, S. aureus cell-free supernatant germinated PrkCSa-expressing spores (Figure S9). Thus, L-Lys containing peptidoglycan can act as a germinant when the Ser/Thr PASTA-containing kinase is changed.

Figure 5. Substrate Specificity of PrkC.

(A) JDB1980 (ΔprkC amyE::Pspac-his6-prkCBs; red) or JDB2017 (ΔprkC amyE::Pspac-his6-prkCSa; black) spores were incubated with different amounts of S. aureus PG for 60 min.

(B) Fifty micrograms His6-PASTABs (PrkCBs) and His6-PASTASa (PrkCSa) were incubated with ~5mg S. aureus PG. Unbound proteins and bound proteins were detected by Coomassie blue and % bound protein was calculated as above. Error bars represent SD for triplicate samples.

Since the extracellular domain of PrkCBs binds to PG (Figure 4C), we examined whether the ability of S. aureus PG to act as a germinant of PrkCSa-expressing spores was due to the ability of the extracellular domain of PrkCSa to bind S. aureus PG. In support of this interpretation, His6-PASTASa bound S. aureus PG much better than His6-PASTABs (Figure 5B). Thus, the ability of PrkCSa-expressing spores to germinate in response to S. aureus PG is at least in part due to the ability of these spores to bind to S. aureus PG.

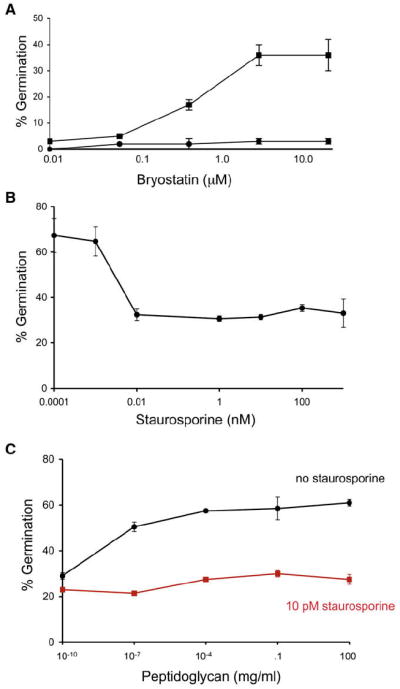

Regulation of Germination by Small-Molecule Kinase Modulators

The cytoplasmic domain of the PrkCBs homolog, M. tuberculosis PknB, is structurally homologous to the catalytic domains of eukaryotic Ser/Thr kinases (Young et al., 2003). This similarity suggests that small molecules known to modulate the activity of these eukaryotic kinases might also modulate PrkC homologs. Oneof these molecules, bryostatin, a natural product synthesized by a marine bacterium, potently activates eukaryotic intracellular Ser/Thr kinases through direct binding to the phorbol ester binding site (Hale et al., 2002). We examined whether bryostatin activated PrkC by incubating wild-type B. subtilis spores with a range of bryostatin concentrations. These spores underwent germination, achieving a maximum of ~40% germination in the presence of 1.0 μM bryostatin (Figure 6A). Bryostatin treatment of ΔprkC spores had no effect (Figure 6A), indicating that bryostatin was acting directly on PrkCBs. Thus, activation of PrkC is sufficient to induce germination, even in the absence of a germinant.

Figure 6. Regulation of Germination by Small Molecules.

(A) Wild-type (squares) or ΔprkC (circles) B. subtilis spores were incubated for 60 min with bryostatin at indicated concentrations.

(B) Wild-type spores were incubated for 60 min with 100 ng/ml B. subtilis peptidoglycan in the presence of staurosporine at indicated concentrations.

(C) Wild-type spores were incubated for 60 min with B. subtilis peptidoglycan at indicated concentrations in the presence (red) or absence (black) of 10 pM staurosporine. Error bars represent SD for triplicate samples.

Dormant spores are resistant to treatments that kill vegetative cells such as antibiotics. However, bryostatin-treated wild-type B. subtilis spores become sensitive to the ribosomal antibiotics tetracycline and spectinomycin (Table S2; data not shown). Since these antibiotics are, like bryostatin, small enough to penetrate the spore coat and membrane, dormant spores are probably resistant because they lack the metabolic activity that is the target of these molecules. Thus, bryostatin stimulation of PrkCBs appears to lead to the resumption of metabolic activity, a hallmark of germination.

Staurosporine, a small-molecule ATP mimic, inhibits intracellular eukaryotic Ser/Thr kinases (Ruegg and Burgess, 1989). As with the bryostatin experiments, we asked whether staurosporine would affect PrkC function. Incubation of staurosporine at concentrations as low as 10 pM with spores significantly reduced peptidoglycan-dependent germination (Figure 6B). In contrast, L-alanine germination was unaffected by staurosporine, consistent with the ability of ΔprkC spores to respond to nutrient germinants (data not shown). Increasing amounts of peptidoglycan did not increase germination in the presence of 10 pM staurosporine, indicating that the compound was not competing for binding of the peptidoglycan (Figure 6C). Thus, PrkCBs phosphorylation of a downstream target is essential for transduction of the peptidoglycan germination signal.

DISCUSSION

Metazoans recognize bacterial cells by the presence of microbial-specific molecules such as peptidoglycan that bind to receptors and trigger the activation of cellular pathways mediating the host response to infection (Kaparakis et al., 2007). In addition, peptidoglycan fragments induce cytopathogical changes in the host during bacterial infections and mediate symbiotic interactions between the eukaryotic host and bacteria (Cloud-Hansen et al., 2006). The presence of these molecules is also consistent with the ability of the environment to support microbial growth since they are released by growing bacteria in large quantities. Here, we report that supernatants of growing bacteria, peptidoglycan isolated from a wide variety of bacteria, and purified muropeptides induce germination in dormant bacterial spores. Thus, peptidoglycan fragments serve as a novel mechanism of interspecies bacterial signaling that likely indicates the presence of growing bacteria (Bassler and Losick, 2006).

PrkC is necessary for germination in response to muropeptides, and it is capable of binding peptidoglycan. The ability of peptidoglycan derived from different bacteria to bind to eukaryotic peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRP) is dependent on the identity of a single residue (L-Lys versus m-Dpm) in the stem peptide (Swaminathan et al., 2006), and we observed a similar specificity in the ability of peptidoglycan to stimulate germination of B. subtilis spores. The structure of a PGRP bound to its peptidoglycan substrate (Chang et al., 2006; Lim et al., 2006) identifies the molecular basis of this specificity. While there is no analogous structure of PrkCBs bound to peptidoglycan, it is intriguing that the observed substrate specificities of PGRP and PrkCBs are so similar despite their apparent phylogenetic distance and lack of primary sequence homology. In addition, fragments of PG bind to and activate the Cyr1p adenyl cyclase of Candida albicans, a key component of the hyphal development pathway, suggesting that PG can play a role in nonimmunological physiological responses of eukaryotic cells (Xu et al., 2008).

Mechanism of Spore Germination

The ability of purified muropeptides and cell-free supernatant isolated from a variety of bacteria to germinate B. subtilis spores (Figures 2A and 2B) suggests that muropeptides released by growing bacteria are a general signal for germination. Since spores undergo a small but detectable rate of spontaneous germination (Paidhungat and Setlow, 2000), the ability of these germinated spores to grow will be detected by the still dormant spores in the population because of their release of muropeptides. Finally, the interspecies nature of this signal (Table 1) is consistent with the existence of most bacteria in multispecies consortia and suggests that spore-forming bacteria monitor the growth of diverse microbes in their environment.

Spore germination initially involves a series of biophysical and biochemical events including ion fluxes and spore rehydration that quickly lead to a loss of spore heat resistance (Setlow, 2003). We have shown that PrkC is required for the loss of heat resistance in peptidoglycan-dependent germination where it phosphorylates EF-G, an essential ribosomal GTPase involved in mRNA and tRNA translocation (Savelsbergh et al., 2003). While the effect of phosphorylation on EF-G activity is not known, the activity of eEF-2, the eukaryotic homolog of EF-G, is determined by its phosphorylation state (Ryazanov et al., 1988). Thus, binding of peptidoglycan fragments to the extracellular PASTA-containing domain of PrkCBs could stimulate translation by inducing the intracellular kinase domain of PrkC to phosphorylate EF-G.

Dormant spores contain mRNA and polysomes (Setlow and Kornberg, 1970), and, when disrupted, they incorporate radiolabeled amino acids (Chambon et al., 1968). Recent evidence indicates that spores contain specific mRNA species directly relevant to the physiological context of the organism (Bettegowda et al., 2006). Thus, translation could be the initial biosynthetic step in the transformation of the dormant spore to a metabolically active cell. However, given the complete metabolic dormancy of the spore core, PrkCBs phosphorylation of EF-G is unlikely to be the sole cause of germination. PrkCBs itself, or an unidentified target of the kinase, probably plays a role in the spore rehydration necessary for translation and metabolism.

Chemical Modulation of the Germination Process

The spore-forming bacterium Clostridium difficile causes an increasingly prevalent gastrointestinal colitis that occurs following antibiotic therapy. C. difficile likely survives exposure to antibiotics as spores since the vegetative form is sensitive to antibiotics (Hecht et al., 2007). When germinated, these spores enter vegetative growth where they are now capable of producing the toxins that cause colitis. Interestingly, members of the GerA germination receptor family are absent from the C. difficile genome. However, since there is a PrkC homolog (Sebaihia et al., 2006), this protein may play an essential role in C. difficile germination.

Most clinically relevant antibiotics are derived from soil-dwelling organisms, presumably reflecting interbacterial competition within soil. While these compounds typically target essential pathways in growing cells, we observed that staurosporine acts by blocking germination of dormant spores at very low (~pM) concentrations. Since staurosporine is synthesized by a species of the soil bacterium Streptomyces (Onaka et al., 2002), it is appealing to posit that staurosporine inhibition of spore germination is relevant to interactions between Streptomyces spp. and Bacillus spp. in the environment.

A Conserved Pathway for Relief of Bacterial Dormancy

Many bacteria exist in a state of metabolic dormancy (Keep et al., 2006) that increases their resistance to antibiotics or to other stresses found in nutrient-limited environments. However, the advantages afforded by this state of dormancy are dependent on the ability of the cell to exit this state when conditions conducive to growth become present. Dormant cells of Micrococcus luteus are stimulated to divide (resuscitate) by exposure to non-dormant M. luteus cells, and this stimulation requires the resuscitation- promoting factor (Rpf), a secreted 17 kDa protein that digests peptidoglycan (Mukamolova et al., 2006) into soluble fragments, likely including muropeptides. The ability of the human pathogen M. tuberculosis to reactivate following in vivo latency is affected by the presence of endogenous resuscitation-promoting factors (Tufariello et al., 2006). Since M. tuberculosis PknB is a homolog of PrkC, PknB may also recognize peptidoglycan fragments as a signal that growth-promoting conditions exist and this ability may have important implications for pathogenesis of this organism. Finally, our observations may provide a mechanistic basis for the observation that many microbes require other bacteria in the local environment in order to grow (Kaeberlein et al., 2002).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

General Methods and Bacterial Strains

B. subtilis strains used in this study and relevant construction details are described in that Supplemental Data. B. subtilis spores were prepared by growth to exhaustion in DSM medium, addition of lysozyme (1 mg/ml, 1 hr, 37°C), and SDS (2%) for 20 min at 37°C. Spores were washed three times with dH2O, resuspended in dH2O, and stored at 4°C. JDB1980, JDB2226, JDB2227, and JDB2017 spores carrying inducible copies of the PrkCBs and PrkCSa genes, respectively, were generated as above except that growth in DSM was in the presence of 1 mM IPTG.

Peptidoglycan Isolation

One hundred milliliter cells grown in LB to an OD600 ~1.2 were collected by centrifugation, washed with 0.8% NaCl, resuspended in hot 4% SDS, boiled for 30 min, and incubated at room temperature (RT) overnight. The suspension was then boiled for 10 min and the SDS-insoluble cell wall material was collected by centrifugation at 15k for 15 min at RT. The pellet-containing cell wall peptidoglycan was washed four times with water and finally resuspended in 1 ml sterile water. Boiling twice with 4% SDS with an overnight incubation removes proteins and lipoteichoic acid molecules from the cell wall material (Girardin et al., 2003). The resuspended PG was digested with mutanolysin (10 μg/ml) overnight at 37°C prior to inactivation of mutanolysin at 80°C for 20 min and use of digested PG in germination assays. Peptidoglycan from B. anthracis Sterne, B. megaterium, B. sphaericus, L. innocua, E. coli, E. faecalis, S. aureus Newman, S. pyogenes, and L. casei were prepared similarly. Cell-free supernatant was obtained from B. subtilis PY79 and E. coli DH5α cells grown in TSS medium and from S. aureus Newman cells grown in Davis medium to an OD600 of 1.2 by filtering (0.2 μm) the culture twice.

Purification of Peptidoglycan Fragments

B. subtilis vegetative peptidoglycan was purified, stripped of teichoic acids, and digested with mutanolysin (McPherson and Popham, 2003). Muropeptides were separated by HPLC using a phosphate buffer with a methanol gradient (Atrih et al., 1999), and individual muropeptides were collected upon elution from the HPLC column. The identities of purified muropeptides were verified using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (Gilmore et al., 2004), and muropeptides were quantified relative to commercial purified amino acid standards using amino acid analysis.

Measurement of Germination

Spores were incubated at 108 spores/ml in 50 μl reactions with germinant in germination buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8], 1 mM glucose) for L-alanine or dH20 for muropeptides for 60 min at 37°C and then subjected to wet heat (80°C) for 20 min. Heat-treated samples were diluted 105-fold, and 100 μl of the diluted samples were spread on LB-agar plates, and following overnight incubation at 37°C, CFUs were determined. Loss of heat resistance as compared to that in the case of incubation with buffer (negative control) and 1 mM L-alanine (positive control) served as a marker for spore germination. Percent germination was expressed upon normalization using CFUs obtained with buffer as control, which results in a failure to germinate spores (i.e., no change in CFUs before or after exposure to heat).

Localization of FLAG-PrkC

Spores were decoated (as confirmed by loss of heat resistance), treated with TEP buffer in the presence of lysozyme, DNase, and RNase for 5 min at 37°C, and cooled on ice for 20 min (Paidhungat and Setlow, 2001). Samples were sonicated (five 15 s pulses) and debris was removed by centrifugation (14K, 5 min). The supernatant was centrifuged (100k•g, 1 hr) to isolate the soluble fraction, and the membrane-containing pellet was resuspended in TEP buffer containing 1% Triton. Following separation of protein by SDS-PAGE (8%), the proteins were transferred onto Nitrocellulose membrane prior to detection with anti-FLAG antibodies (Sigma) and ECL substrate (Amersham).

Peptidoglycan Binding

We purified the C-terminal fragment of PrkC (His6-PASTABs) composed of residues 357–648 using Ni2+ affinity chromatography with an E. coli strain carrying pIMS40 that overproduces His6-PASTABs. His6-YycI composed of residues 31–280 was purified using identical methodology with an E. coli strain carrying pIMS36. His6-AcmA composed of residues 243–439 using an E. coli strain carrying pIMS42 and His6-PASTASa composed of residues 378–644 using an E. coli strain carrying pIMS44 were purified using identical methodology. We separately incubated 50 μg of proteins with purified B. subtilis or S. aureus peptidoglycan (~5 mg) in 20 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 500 mM NaCl for 30 min at 4°C. We centrifuged (10 min, 15k) to remove the supernatant (soluble fraction), washed the pellet twice, resuspended it in 2% SDS, and incubated at RT for 1 hr. Bound fraction (insoluble fraction) was recovered by removing the insoluble pellet by centrifugation. Fractions consisting of unbound soluble protein and insoluble bound protein and the wash were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The gels were stained with Coomassie blue and the differences in the amounts of His6-PASTA in the two fractions were determined by measurement of the appropriate bands using ImageJ (NIH).

Detection of Phosphorylated EF-G

Spores were isolated from 100 ml cultures, decoated, and treated either with non-germinant buffer or cell-free supernatant prior to treatment with TEP buffer (Lysozyme/DNase/RNase) and sonicated to remove debris. The resulting supernatant was subjected to ultracentrifugation at 100k•g for 1 hr. The soluble S100 fraction from each sample was subjected to immunoprecipitation with EF-G antibodies (kind gift of W. Wintermeyer) prebound to Protein A Dynabeads (Invitrogen), and immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by 6% SDS-PAGE followed by transfer of proteins onto nitrocellulose membranes. Immunoblotting was performed with either EF-G antibodies or phosphothreonine antibodies (Zymed, Invitrogen) to detect phosphorylated EF-G using ECL substrate (Amersham).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Aaron Mitchell and Howard Shuman for helpful discussions and Adriano Henriques, Marjorie Russel, Howard Shuman, and Leslie Vosshall for critically reading the manuscript. We thank C. Price and P. Setlow for B. subtilis strains and D. Garsin, F. Lowy, D. Portnoy, and A. Ratner for additional bacterial strains. This work was supported by startup funds from the Department of Microbiology, Columbia University to J.D. and by NIH grant GM56695 to D.L.P. J.D. is an Irma T. Hirschl Trust Scholar.

Footnotes

Supplemental Data include two tables, nine figures, Supplemental Experimental Procedures, and Supplemental References and can be found with this article online at http://www.cell.com/supplemental/S0092-8674(08)01128-8.

References

- Atrih A, Bacher G, Allmaier G, Williamson MP, Foster SJ. Analysis of peptidoglycan structure from vegetative cells of Bacillus subtilis 168 and role of PBP 5 in peptidoglycan maturation. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3956–3966. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.13.3956-3966.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassler BL, Losick R. Bacterially speaking. Cell. 2006;125:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettegowda C, Huang X, Lin J, Cheong I, Kohli M, Szabo SA, Zhang X, Diaz LA, Jr, Velculescu VE, Parmigiani G, et al. The genome and transcriptomes of the anti-tumor agent Clostridium novyi-NT. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1573–1580. doi: 10.1038/nbt1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge TJ. Structures of gram-negative cell walls and their derived membrane vesicles. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4725–4733. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.4725-4733.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambon P, Deutscher MP, Kornberg A. Biochemical studies of bacterial sporulation and germination. X. Ribosomes and nucleic acids of vegetative cells and spores of Bacillus megaterium. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:5110–5116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CI, Chelliah Y, Borek D, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Deisenhofer J. Structure of tracheal cytotoxin in complex with a heterodimeric pattern-recognition receptor. Science. 2006;311:1761–1764. doi: 10.1126/science.1123056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloud-Hansen KA, Peterson SB, Stabb EV, Goldman WE, McFaa-Ngai MJ, Handelsman J. Breaching the great wall: peptidoglycan and microbial interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:710–716. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Elia MA, Millar KE, Beveridge TJ, Brown ED. Wall teichoic acid polymers are dispensable for cell viability in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:8313–8316. doi: 10.1128/JB.01336-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta A, Datta P, Kundu M, Basu J. The serine/threonine kinase PknB of Mycobacterium tuberculosis phosphorylates PBPA, a penicillin-binding protein required for cell division. Microbiology. 2006;152:493–504. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle RJ, Chaloupka J, Vinter V. Turnover of cell walls in microorganisms. Microbiol Rev. 1988;52:554–567. doi: 10.1128/mr.52.4.554-567.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driks A. Bacillus subtilis spore coat. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:1–20. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.1-20.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert C, Lecerf M, Dubost L, Arthur M, Mesnage S. Functional analysis of AtlA, the major N-acetylglucosaminidase of Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:8513–8519. doi: 10.1128/JB.01145-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaidenko TA, Kim TJ, Price CW. The PrpC serine-threonine phosphatase and PrkC kinase have opposing physiological roles in stationary-phase Bacillus subtilis cells. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:6109–6114. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.22.6109-6114.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore ME, Bandyopadhyay D, Dean AM, Linnstaedt SD, Popham DL. Production of muramic delta-lactam in Bacillus subtilis spore peptidoglycan. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:80–89. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.1.80-89.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardin SE, Travassos LH, Herve M, Blanot D, Boneca IG, Philpott DJ, Sansonetti PJ, Mengin-Lecreulx D. Peptidoglycan molecular requirements allowing detection by Nod1 and Nod2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41702–41708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodell EW, Schwarz U. Release of cell wall peptides into culture medium by exponentially growing Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:391–397. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.1.391-397.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale KJ, Hummersone MG, Manaviazar S, Frigerio M. The chemistry and biology of the bryostatin antitumour macrolides. Nat Prod Rep. 2002;19:413–453. doi: 10.1039/b009211h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M, Yang K, Hashimoto M, Park JH, Kim YG, Fujimoto Y, Nunez G, Fukase K, Inohara N. Differential release and distribution of Nod1 and Nod2 immunostimulatory molecules among bacterial species and environments. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29054–29063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht DW, Galang MA, Sambol SP, Osmolski JR, Johnson S, Gerding DN. In vitro activities of 15 antimicrobial agents against 110 toxigenic clostridium difficile clinical isolates collected from 1983 to 2004. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:2716–2719. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01623-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson KD, Corfe BM, Kemp EH, Feavers IM, Coote PJ, Moir A. Localization of GerAA and GerAC proteins in the Bacillus subtilis spore. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4317–4322. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.14.4317-4322.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hungerer KD, Tipper DJ. Cell wall polymers of Bacillus sphaericus 9602. I. Structure of the vegetative cell wall peptidoglycan. Biochemistry. 1969;8:3577–3587. doi: 10.1021/bi00837a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G, Dyson P. Evolution of transmembrane protein kinases implicated in coordinating remodeling of gram-positive peptidoglycan: inside versus outside. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:7470–7476. doi: 10.1128/JB.00800-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeberlein T, Lewis K, Epstein SS. Isolating “uncultivable” microorganisms in pure culture in a simulated natural environment. Science. 2002;296:1127–1129. doi: 10.1126/science.1070633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaparakis M, Philpott DJ, Ferrero RL. Mammalian NLR proteins; discriminating foe from friend. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:495–502. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keep NH, Ward JM, Cohen-Gonsaud M, Henderson B. Wake up! Peptidoglycan lysis and bacterial non-growth states. Trends Microbiol. 2006;14:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JH, Kim MS, Kim HE, Yano T, Oshima Y, Aggarwal K, Goldman WE, Silverman N, Kurata S, Oh BH. Structural basis for preferential recognition of diaminopimelic acid-type peptidoglycan by a subset of peptidoglycan recognition proteins. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8286–8295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madec E, Laszkiewicz A, Iwanicki A, Obuchowski M, Seror S. Characterization of a membrane-linked Ser/Thr protein kinase in Bacillus subtilis, implicated in developmental processes. Mol Microbiol. 2002;46:571–586. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauck J, Chan L, Glaser L. Turnover of the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:1820–1827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson DC, Popham DL. Peptidoglycan synthesis in the absence of class A penicillin-binding proteins in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:1423–1431. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.4.1423-1431.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamolova GV, Murzin AG, Salina EG, Demina GR, Kell DB, Kaprelyants AS, Young M. Muralytic activity of Micrococcus luteus Rpf and its relationship to physiological activity in promoting bacterial growth and resuscitation. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:84–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson WL, Munakata N, Horneck G, Melosh HJ, Setlow P. Resistance of Bacillus endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:548–572. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.3.548-572.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onaka H, Taniguchi S, Igarashi Y, Furumai T. Cloning of the staurosporine biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces sp. TP-A0274 and its heterologous expression in Streptomyces lividans. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2002;55:1063–1071. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.55.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paidhungat M, Setlow P. Role of ger proteins in nutrient and nonnutrient triggering of spore germination in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2513–2519. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.9.2513-2519.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paidhungat M, Setlow P. Localization of a germinant receptor protein (GerBA) to the inner membrane of Bacillus subtilis spores. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3982–3990. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.13.3982-3990.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruegg UT, Burgess GM. Staurosporine, K-252 and UCN-01: potent but nonspecific inhibitors of protein kinases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1989;10:218–220. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(89)90263-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryazanov AG, Shestakova EA, Natapov PG. Phosphorylation of elongation factor 2 by EF-2 kinase affects rate of translation. Nature. 1988;334:170–173. doi: 10.1038/334170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli E, Liddington RC, Mohan MA, Hoch JA, Szurmant H. The crystal structure of Bacillus subtilis YycI reveals a common fold for two members of an unusual class of sensor histidine kinase regulatory proteins. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:3290–3295. doi: 10.1128/JB.01937-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savelsbergh A, Katunin VI, Mohr D, Peske F, Rodnina MV, Wintermeyer W. An elongation factor G-induced ribosome rearrangement precedes tRNA-mRNA translocation. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1517–1523. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleifer KH, Kandler O. Peptidoglycan types of bacterial cell walls and their taxonomic implications. Bacteriol Rev. 1972;36:407–477. doi: 10.1128/br.36.4.407-477.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebaihia M, Wren BW, Mullany P, Fairweather NF, Minton N, Stabler R, Thomson NR, Roberts AP, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Wang H, et al. The multidrug-resistant human pathogen Clostridium difficile has a highly mobile, mosaic genome. Nat Genet. 2006;38:779–786. doi: 10.1038/ng1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlow P. Spore germination. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:550–556. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setlow P, Kornberg A. Biochemical studies of bacterial sporulation and germination. 23. Nucleotide metabolism during spore germination. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:3645–3652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K, Gupta M, Krupa A, Srinivasan N, Singh Y. EmbR, a regulatory protein with ATPase activity, is a substrate of multiple serine/threonine kinases and phosphatase in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEBS J. 2006;273:2711–2721. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steen A, Buist G, Leenhouts KJ, El Khattabi M, Grijpstra F, Zomer AL, Venema G, Kuipers OP, Kok J. Cell wall attachment of a widely distributed peptidoglycan binding domain is hindered by cell wall constituents. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23874–23881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211055200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan CP, Brown PH, Roychowdhury A, Wang Q, Guan R, Silverman N, Goldman WE, Boons GJ, Mariuzza RA. Dual strategies for peptidoglycan discrimination by peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:684–689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507656103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufariello JM, Mi K, Xu J, Manabe YC, Kesavan AK, Drumm J, Tanaka K, Jacobs WR, Jr, Chan J. Deletion of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis resuscitation-promoting factor Rv1009 gene results in delayed reactivation from chronic tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2985–2995. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.5.2985-2995.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XL, Lee RT, Fang HM, Wang YM, Li R, Zou H, Zhu Y, Wang Y. Bacterial peptidoglycan triggers Candida albicans hyphal growth by directly activating the adenylyl cyclase Cyr1p. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeats C, Finn RD, Bateman A. The PASTA domain: a betalactam-binding domain. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:438. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young TA, Delagoutte B, Endrizzi JA, Falick AM, Alber T. Structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis PknB supports a universal activation mechanism for Ser/Thr protein kinases. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:168–174. doi: 10.1038/nsb897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.