Abstract

In 2006, TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43), a highly conserved nuclear protein, was identified as the major disease protein in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and in the most common variant of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), FTLD-U, which is characterized by cytoplasmic inclusions that stain positive for ubiquitin but negative for tau and α-synuclein. Since then, rapid advances have been made in our understanding of the physiological function of TDP-43 and the role of this protein in neurodegeneration. These advances link ALS and FTLD-U (now designated FTLD-TDP) to a shared mechanism of disease. In this Review, we summarize the current evidence regarding the normal function of TDP-43 and the TDP-43 pathology observed in FTLD-TDP, ALS, and other neurodegenerative diseases wherein TDP-43 pathology co-occurs with other disease-specific lesions (for example, with amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer disease). Moreover, we discuss the accumulating data that support our view that FTLD-TDP and ALS represent two ends of a spectrum of primary TDP-43 proteinopathies. Finally, we comment on the importance of recent advances in TDP-43-related research to neurological practice, including the new opportunities to develop better diagnostics and disease-modifying therapies for ALS, FTLD-TDP, and related disorders exhibiting TDP-43 pathology.

Introduction

Over 100 years have passed since the Czech neurologist Arnold Pick published his descriptions of a progressive dementia that differed both clinically and pathologically from Alzheimer disease (AD).1 Clinically, Pick’s patients were notable for their language and behavioral deficits rather than the memory impairment that usually characterizes AD.2,3 Pathologically, the brains of these patients showed patterns of circumscribed atrophy, with a marked loss of volume in the frontal and temporal lobes causing a sharp demarcation between these regions and other parts of the brain.4 The dementia that Pick first described has come to be known as frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) and, in the century that has elapsed since these first descriptions, histopathological, biochemical, and genetic advances have led to a rich understanding of this non-AD dementia.5–8

By 2006, most cases of FTLD were largely recognized to fall into one of two different neuropathological—and, by extension, pathogenic—subtypes. The first subtype was characterized by abnormal accumulations of the microtubule-stabilizing protein tau (FTLD-tau), whereas the second was characterized by inclusion bodies that did not contain tau or α-synuclein but, rather, stained positive for ubiquitin (FTLD-U).9,10 Cases falling into the former group had certain unifying characteristics—not least of which were the tau-immunopositive inclusions—that argued for FTLD-tau to be considered as a distinct disease entity. Notably, a subset of patients with FTLD-tau had underlying mutations in the gene encoding tau, MAPT.11,12 Together, these discoveries provided compelling evidence that tau pathology was sufficient to cause sporadic and familial neurodegenerative diseases (now referred to as ‘tauopathies’) in the absence of amyloid-β (Aβ) deposits or other brain amyloid accumulations. Whether FTLD-U represented a single disease entity or merely a collection of cases unified by a lack of abnormal tau immunopositivity remained unclear.

Two landmark discoveries in 2006 laid the groundwork for our current understanding of the pathobiology of FTLD-U. First, two groups independently reported that a subset of FTLD-U cases were associated with mutations in the progranulin gene (GRN).13,14 Second, TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) was identified by Neumann et al. as the main protein component of the ubiquitinated inclusions found in most cases of FTLD-U.15 The second discovery prompted a modification of FTLD nomenclature, with the term FTLD-TDP replacing FTLD-U to describe such cases.16 Subsequently, TDP-43 lesions were shown to be the neuropathological hallmarks of GRN mutation-associated FTLD.17 The study by Neumann et al. also showed that TDP-43 was the main protein constituent of the ubiquitinated inclusions found in the the most common adult form of motor neuron disease (MND), namely amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).15 The determination of TDP-43 as the main disease protein in both FTLD-TDP and ALS drew attention to the already known but possibly underappreciated links between these disorders. Of note, studies had shown that ≈15% of patients with FTLD developed MND,10,18 ≈50% of patients with MND developed varying degrees of cognitive impairment,19 and ALS and FTLD cosegregated in some families.20

In this Review, we summarize current evidence regarding the physiological function of TDP-43 and provide an overview of the TDP-43 pathology found in FTLD-TDP, ALS and other neurodegenerative diseases. In addition, we evaluate the potential role of TDP-43 in the pathogenesis of FTLD-TDP and ALS, and discuss the accumulating data that support our view that these diseases can be considered as two ends of a spectrum of neurodegenerative disorders characterized as primary TDP-43 proteinopathies. Finally, we comment on the importance of the developments in TDP-43-related research to the practice of neurology.

Key points

Genetic and neuropathological evidence indicate that TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) is the main disease-associated protein in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and in many cases of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD)

FTLD with TDP-43 positive inclusions (FTLD-TDP) and ALS might represent two ends of a disease spectrum of primary TDP-43 proteinopathies

TDP-43 pathology seems to be a secondary feature of several neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease and Huntington disease

Under physiological conditions, TDP-43 resides in the nuclear compartment and is involved in the regulation of gene expression

In neurodegenerative diseases, TDP-43 is primarily found in cytoplasmic inclusions, where the protein is poorly soluble, hyperphosphorylated, ubiquitinated, and cleaved into small fragments

Progress in TDP-43-related research has been rapid, with TDP-43 biomarkers and transgenic mouse models emerging within 3 years of the initial reports linking this protein to FTLD-TDP and ALS

Physiological function

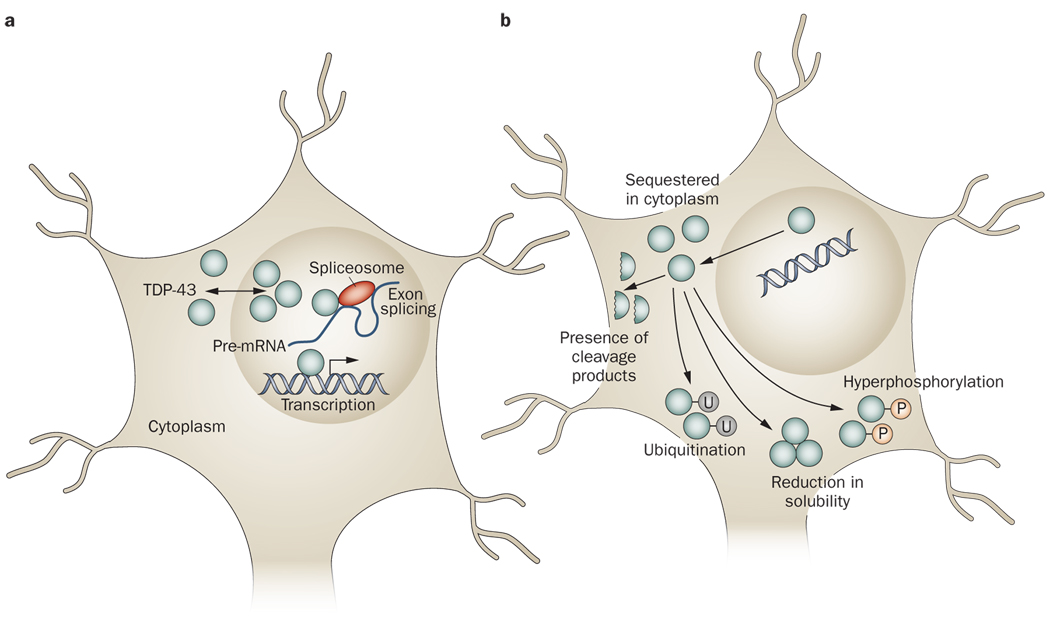

TDP-43 is a 414 amino acid protein of 43 kDa encoded by the TARDBP gene on chromosome 1. Under physiological conditions, TDP-43 is predominantly nuclear,21 although the protein is synthesized in the cytoplasmic compartment and is capable of shuttling between the nucleus and cytoplasm.22,23 The physiological function of TDP-43 is still incompletely characterized; however, the available evidence suggests this protein has several roles in the regulation of gene expression (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Physiological and pathophysiological TDP-43. a | Under physiological conditions, TDP-43 primarily resides in the nucleus, although the protein has the capacity to shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. TDP-43 has been reported to have roles in regulating gene expression at the transcriptional level, regulating gene splicing, and stabilizing mRNA. b | Under pathophysiological conditions, TDP-43 is cleared from the nuclear compartment and accumulates in the cytoplasm. Pathological TDP-43 has been demonstrated to be hyperphosphorylated and/or ubiquitinated. Furthermore, small carboxy-terminal fragments of TDP-43 can be found in the disease state. Pathological TDP-43 is also less soluble than TDP-43 under physiological conditions, possibly making the former more prone to aggregation. The changes that occur in the nature of TDP-43 under pathophysiological conditions might result in various loss-of-function or toxic-gain-of-function mechanisms of pathogenesis. Abbreviation: mRNA, messenger RNA; P, phosphate group; TDP-43, TAR DNA-binding protein 43; U, ubiquitin group.

TDP-43 was first identified in a screen for protein factors that were capable of binding the long terminal repeat transactive response element of HIV-1.24 Subsequent studies have shown that TDP-43 can bind both DNA and RNA.25,26 TDP-43 has been demonstrated to act as a transcriptional repressor of HIV-1 gene expression24 and for the mammalian gene SP-10,27,28 presumably through the protein’s ability to bind DNA. TDP-43 has also been shown to be involved in the exon splicing of several genes, including CFTR,25,29,30 APOA2,31 and SMN, a gene associated with MND.32 The capacity of TDP-43 to interact with RNA, including messenger RNA (mRNA) and pre-mRNA, probably underlies this role in exon splicing. Other reported functions of TDP-43 include stabilization of NEFL mRNA33 and modulation of CDK6 gene expression.34

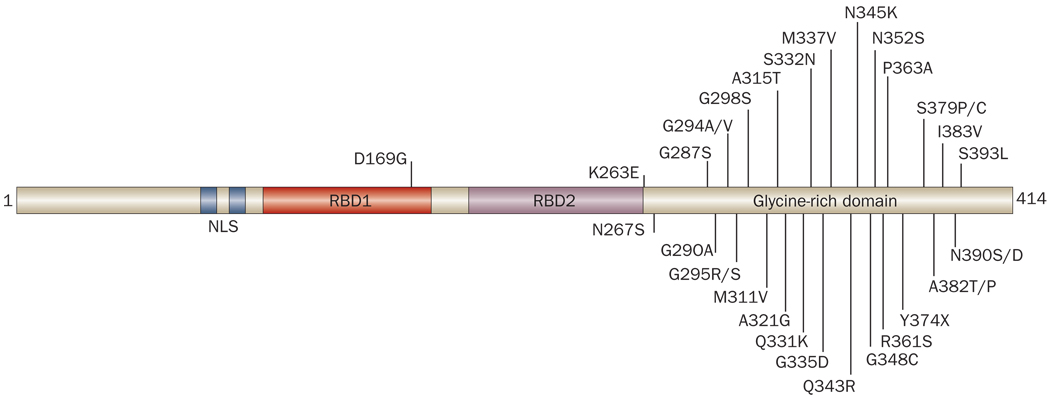

TDP-43 possesses two evolutionarily conserved RNA-binding domains (RBDs) and a carboxy-terminal glycine-rich domain. This structure places TDP-43 in the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) subclass of 2xRBD-Gly proteins (Figure 2).35 Like TDP-43, the other hnRNPs have a role in the regulation of gene splicing.35,36 In addition, the RBDs of TDP-43 show notable homology to the equivalent domains of the other members of the hnRNP subclass.32 By contrast, the glycine-rich domain of TDP-43 shows limited homology to other hnRNPs and is not always present beyond mammals.32,37 This domain, however, seems to be necessary for some of the most well-characterized functions of TDP-43, including the protein’s role as a gene splicing factor.38

Figure 2.

Domain structure and disease-associated mutations of TDP-43. TDP-43 shares structural similarities with heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins, with a domain structure consisting of two RBDs followed by a glycine-rich domain. At least 32 different mutations (indicated by the single letter amino acid code) in TARDBP—the gene encoding TDP-43—have been reported to cause disease in humans. Most of these mutations occur within the glycine-rich domain. At least two of these mutations (Gly295Ser and Lys263Glu) might cause frontotemporal lobar degeneration, although the majority of TARDBP mutations have been reported in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Abbreviations: NLS, nuclear localization signal; RBD, RNA binding domain; TDP-43, TAR DNA-binding protein 43.

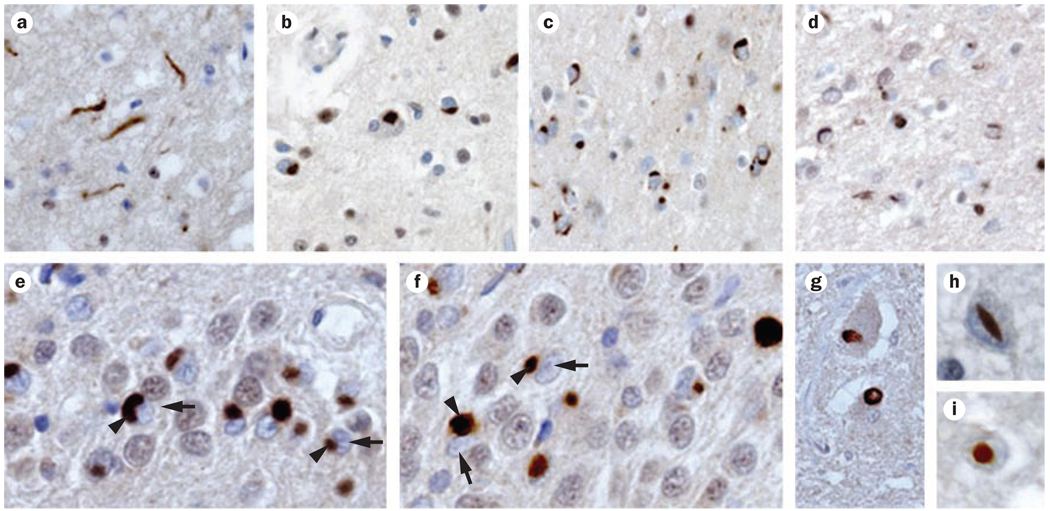

Pathology

TDP-43 pathology can be found in many neurodegenerative diseases (Box 1). In FTLD-TDP and ALS, TDP-43 pathology is the most prominent histopathological feature (Figure 3). In many other disorders, including AD and Parkinson disease (PD), TDP-43 pathology is an important but secondary histopathological feature of disease. In some patients, the topography of TDP-43 pathology accords with the primary clinical symptomology (for example, severe motor cortex pathology in ALS), but in other cases no such association exists (for example, medial temporal lobe pathology in PD).

Box 1 Diseases characterized by TDP-43 pathology

Diseases with TDP-43 pathology as a primary histopathological feature

FTLD-TDP

ALS

Overlap syndromes presenting with features of ALS and FTLD-TDP

Rare disorders (Perry syndrome, FTLD–inclusion body myopathy–Paget syndrome)

Diseases with TDP-43 pathology as a secondary histopathological feature

Alzheimer disease

PD and related disorders (PD with dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies plus Alzheimer disease)

Huntington disease

Rare disorders (Guam ALS, Guam ALS-PD)

Abbreviations: ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; FTLD-TDP, FTLD with TDP-43-positive inclusions; PD, Parkinson disease; TDP-43, TAR DNA-binding protein 43.

Figure 3.

TDP-43 histopathology. Immunohistochemistry with an anti-TDP-43 antibody reveals robust staining of ubiquitinated inclusions (brown staining). TDP-43 pathology in FTLD-TDP can be classified into four subtypes, three of which are shown here in frontal cortex tissue: a | type 1 pathology, b | type 2 pathology and c,d | type 3 pathology. e,f | Immunostaining showing TDP-43 inclusions (arrowheads) and nuclear clearance (arrows) in neurons in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Other morphologies of TDP-43-immunoreactive histopathology include g | intranuclear inclusions, h | lentiform inclusions, and i | round inclusions in motor neurons of the spinal cord. Abbreviations; FTLD-TDP, frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43 inclusions; TDP-43, TAR DNA-binding protein 43. Reprinted with permission from AAAS © Neumann, M. et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 314, 130–133 (2006).

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration

In 2006, Neumann et al. reported that TDP-43 was the main protein component of the ubiquitinated inclusions found in most cases of FTLD-U and in ALS.15 This discovery was rapidly confirmed by others39 and further verified in subsequent studies of familial and sporadic cases of FTLD-TDP.17,40,41

In FTLD-TDP, TDP-43 pathology is found throughout the CNS, although the occipital cortex and cerebellum remain relatively unaffected.42 The histopathological TDP-43 findings found in cases of FTLD-TDP fall into four main subtypes (Figure 3). Type 1 pathology is characterized by a relative abundance of cytoplasmic TDP-43 inclusions in long neuritic profiles in superficial cortical layers, whereas type 2 pathology is delineated by a predominance of such inclusions in both the superficial and deep cortical layers. In type 3 pathology, abundant cytoplasmic TDP-43 inclusions are found mainly in the superficial cortical layers, and in type 4 pathology, which is associated with mutations in the VCP gene (see below), most TDP-43 inclusions are nuclear.39,40,43 The TDP-43 inclusions observed in ALS have a different distribution pattern from inclusions in FTLD-TDP, as ALS predominantly affects the upper and lower motor neurons. Thus, ALS with TDP-43 inclusions is categorized as a type 5 TDP-43 pathology (see below).41

For all subtypes of pathology, neurons with cytoplasmic inclusions of TDP-43 exhibit clearance of ‘normal’ TDP-43 from the nucleus.42 This observation is consistent with an in vitro study which showed that mutant TDP-43, abnormally localized to the cytoplasm, seemed to sequester normal endogenous TDP-43 to this cellular compartment.22 The importance of the various histopathological FTLD-TDP subtypes remains to be established. Of note, however, all neuropathologically characterized cases of FTLD-TDP associated with GRN mutations have shown type 3-like TDP-43 pathology.44,45 These findings suggest mechanistic differences between subtypes of FTLD-TDP with varying TDP-43 pathology.

A small proportion of FTLD-U cases (<10%) do not demonstrate TDP-43 pathology. Many of these cases have been reported to harbor pathological inclusions containing the ALS-associated protein fused in sarcoma (FUS).46 Mutations in the gene encoding this protein have been shown to be present in rare kindreds with familial ALS47,48 and in some cases of sporadic ALS.49,50

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

The vast majority of ALS cases are sporadic, and most of these cases harbor TDP-43 inclusions.51–53 TDP-43 inclusions are also found in patients with familial ALS, with the notable exception of cases associated with mutations in the superoxide dismutase gene (SOD1).54 Thus, SOD1-associated ALS might differ in terms of disease mechanism from the majority of sporadic and familial ALS cases with TDP-43 pathology. TDP-43 histopathology in ALS is characterized by cytoplasmic inclusions of a skein-like or dense granular appearance and by clearance of TDP-43 from the nucleus (Figure 3).52 Some degree of TDP-43 pathology in ALS can be found throughout the brain; however, the most severely affected areas of the CNS are the motor cortex, the spinal cord, the basal ganglia, and the thalamus. This distribution of pathology explains why ALS with TDP-43 inclusions is considered to represent a distinct pathological subtype (type 5).52

Overlap cases

Many cases of FTLD or ALS can be readily categorized accordingly to the most prominent clinical features associated with each condition. However, a small, but still substantial, proportion of suspected cases of FTLD or ALS show features of both FTLD and MND (or ALS). Some of these patients first present with cognitive impairment (sometimes called FTLD–MND), while others initially present with motor impairment (sometimes called ALS-plus). TDP-43 pathology is the primary histopathological feature of such ‘overlap’ cases, and comprises TDP-43-positive inclusions or granular staining in the cytoplasm and an absence of nuclear TDP-43 immunoreactivity.40 Not surprisingly, the topographical distribution of TDP-43 lesions in these cases lies somewhere between the distributions observed in FTLD-TDP (mainly telencephalic lesions) and ALS (lesions mainly affecting upper and lower motor neurons).40,42

Other diseases with prominent pathology

In addition to FTLD-TDP, ALS and their overlap syndromes, several rare conditions have TDP-43 pathology as their primary histopathological feature. Mutations in VCP have been associated with a syndrome complex consisting of FTLD, inclusion body myopathy and Paget disease of the bone.55 As noted above, the TDP-43 pathology in patients with this disease forms a separate pathological subtype (type 4). In contrast to pathological subtypes 1–3, the neuronal TDP-43 inclusions described in VCP-associated cases are almost exclusively nuclear and spare the dentate gyrus. TDP-43 pathology has also been found in muscle cells in these cases, where the inclusions are a prominent histopathological feature.56,57 Reports of inclusion body myositis—an inflammatory form of inclusion body myopathy that is not associated with mutations in VCP—have described abnormal sarcoplasmic TDP-43 staining, again as the most notable histopathological feature of the disease.57,58 Finally, prominent TDP-43 pathology, largely confined to the basal ganglia, has been demonstrated in Perry syndrome, a clinical entity characterized by early-onset parkinsonism, severe weight loss, and depression.59

Mutations in the gene encoding the microtubule-associated protein dynactin (DCTN1) have been reported to be the cause of Perry syndrome.60 Interestingly, DCTN1 mutations have also been associated with MND61 and FTLD.62 Together, these genetic findings suggest a mechanistic link between Perry syndrome, FTLD and ALS. One should also note that mutations in GRN, VCP or DCTN1 all cause neurodegenerative diseases wherein the underlying pathology is not characterized by accumulation of the protein encoded by the mutant gene but, rather, features TDP-43 inclusions. The reasons for these findings are enigmatic; however, we speculate that a better understanding of these disorders could provide important insights into the mechanisms underlying TDP-43-mediated neurodegeneration.

Diseases with secondary pathology

In addition to neurodegenerative diseases in which TDP-43 pathology is the primary histopathological feature (primary TDP-43 proteinopathies), TDP-43 inclusions can be detected in several disorders as secondary pathological features (secondary TDP-43 proteinopathies).

To date, TDP-43 inclusions have been reported to be secondary pathological features of AD, PD (and related disorders), and Huntington disease (HD), as well as several rarer diseases, including Guam ALS and Guam ALS–PD.63–65 In AD, TDP-43 pathology is found in over 50% of cases, and is usually localized to the medial temporal lobe.66–70 The TDP-43 pathology observed in PD, PD with dementia, and dementia with Lewy bodies plus AD is also localized to this region of the brain, and affects up to 60% of cases.67,68,71 Finally, one study has reported that in all cases of HD examined (10 in total), pathological TDP-43 co-localized with mutant huntingtin in cytoplasmic inclusions.72

Evidence for pathogenicity

The abundant TDP-43 pathology found in the disorders highlighted above suggests a pathogenic role for this protein in disease. Such correlative observations, however, do not prove that TDP-43 mediates neurodegeneration.73 We believe that empirical data from humans and in vitro models, which show dramatic changes in the properties of TDP-43 under pathological conditions, support the concept of a TDP-43 proteinopathy.

Disease-associated protein characteristics

TDP-43 is abundantly expressed in neurons, glia, and many other cell types. The appearance of this protein across these cell types differs markedly between healthy tissue and tissue affected by disease. Many studies have shown that TDP-43 in tissue taken from cases of FTLD-TDP or ALS (but not in tissue taken from controls) is often hyperphosphorylated, cleaved, ubiquitinated, mislocalized and poorly soluble (Figure 1).15,39,74–76 These data beg the question of what functional consequences might ensue from the observed differences between normal and abnormal TDP-43.

Hyperphosphorylation of TDP-43 at specific amino acid residues has been shown to clearly differentiate disease-associated TDP-43 from TDP-43 in normal brain tissue.77–79 The biological activity of many proteins is regulated by their phosphorylation state, and dysregulation of protein phosphorylation is a feature of several neurodegenerative diseases. For example, we and others have demonstrated that hyperphosphorylation of tau—a process implicated in the pathogenesis of FTLD-tau and AD—leads to loss of the protein’s normal ability to assemble and maintain microtubules, as well as a propensity for the molecule to aggregate into paired helical filaments.80 In turn, these changes in tau lead to neuronal dysfunction and degeneration. The consequences of TDP-43 hyperphosphorylation remain unclear; however, loss-of-function and/or gain-of-toxic-function mechanisms conferred by such post-translational modification might have a role in TDP-43-mediated neurodegeneration.

TDP-43 extracted from disease-associated tissue is markedly less soluble than TDP-43 from normal tissue.15 The functional consequence of this reduction in solubility is uncertain, although the propensity of insoluble TDP-43 to aggregate in the cytoplasm or, less commonly, in the nucleus suggests a gain-of-toxic-function mechanism for TDP-43 in disease. This altered property of TDP-43 might be linked to phosphorylation of the protein.

Small species of TDP-43 of ≈25 kDa can be detected in pathological specimens from patients with ALS or FTLD-TDP, but not in normal brain tissue.15 These species are believed to be carboxy-terminal fragments of TDP-43 generated through cleavage of the full-length protein.77 Arg208 has been identified as one of the cleavage sites.81 Studies of the TDP-43 carboxy-terminal fragments are still in their early stages; however, work in yeast82 and in human cell lines83,84 suggests that these fragments might cause inclusion formation and/or cellular toxicity. Remarkably, while these fragments accumulate in telencephalic regions, the spinal cord seems to be relatively free of these TDP-43 species,85 suggesting that pathological cleavage of TDP-43 is not an absolute requirement for neurodegeneration, at least not in the spinal cord.

In disease-associated tissue, TDP-43 has consistently been shown to be ubiquitinated—a protein modification that is seen in various neurodegenerative diseases, including the tauopathies. Ubiquitination might represent an effort by the cell to target pathological TDP-43 for proteosomal degradation, although the reasons for and consequences of TDP-43 ubiquitination remain uncertain.72

The nuclear clearing of TDP-43 is a hallmark of cells that harbor TDP-43 inclusions. Such clearing has been shown in neurons15 and glia from human tissue samples,52 various cell lines,22,84 and muscle cells from VCP mutation-bearing patients.58 As described previously, physiological TDP-43 functions in the regulation of gene expression. To fulfill this role, TDP-43 must have access to the nucleus of a cell. Thus, the exclusion of TDP-43 from the nuclear compartment will probably result in some degree of loss of the protein’s function. Indeed, we have reported partial loss of the normal splicing function of TDP-43 in cell culture models that recapitulate the cytoplasmic localization of TDP-43 in pathology.81 Furthermore, we have shown a marked dysregulation of gene expression in FTLD-TDP.86

To summarize, a variety of features distinguish normal TDP-43 from disease-associated TDP-43, including hyperphosphorylation, relative insolubility, a propensity to be cleaved, ubiquitination, and mislocalization to the cytoplasm. These features suggest various loss-of-function and gain-of-toxic-function mechanisms for TDP-43 in disease pathogenesis (Figure 1).

Data from other disease-associated proteins

Mutations in SMN can cause a pediatric form of MND called spinal muscular atrophy,87 while some familial cases of ALS result from mutations in FUS.47,48 Thus, the proteins encoded by these two genes, like TDP-43, are implicated in the degeneration of motor neurons. The similarities among these proteins do not end there, as all three proteins are known to function in the maturation of RNA—a process that involves shuttling of each protein between the nucleus and cytoplasm.

SMN forms part of a complex (with small nuclear ribonucleoproteins) that, like TDP-43, is involved in pre-mRNA splicing. The assembly of the complex, in which SMN has a pivotal role, takes place in the cytoplasm, and is followed by transport of the complex into the nucleus for maturation of the small nuclear ribonucleoproteins.88

FUS bears even stronger similarities to TDP-4389 than does SMN. Like TDP-43, FUS is predominantly nuclear under physiological conditions, and is cleared from the nucleus and accumulates in the cytoplasm in disease states.47,48 Furthermore, as with TDP-43, FUS can bind both RNA and DNA, and is believed to function in the regulation of RNA splicing and gene expression at a transcriptional level.90

The similarities between SMN, FUS and TDP-43, in terms of function and cellular distribution in health and disease, suggest that abnormal RNA processing might be an important common mechanism underlying various types of MND. Moreover, these commonalities suggest that TDP-43 is involved in disease pathogenesis, rather than acting as an innocent bystander.

Genetic evidence

The preceding sections make a case for the involvement of TDP-43 in disease pathogenesis largely on the basis of neuropathological studies. The evidence from such studies is persuasive and similar to data that initially linked Aβ and tau to the underlying molecular biology of AD, and tau to disease mechanisms in other tauopathies. As subsequently occurred for Aβ and tau, strong supportive evidence for a role for TDP-43 in disease pathogenesis has also come from genetic studies.

The discovery that TDP-43-positive inclusions characterize FTLD-TDP and ALS was quickly followed by efforts from multiple groups to determine whether mutations in TARDBP are associated with these diseases. The first mutations were described in 2008, with missense mutations in the TARDBP gene being described in both familial and sporadic cases of ALS.91–102 To date, over 30 different mutations from 19 patients with familial ALS and 31 patients with sporadic ALS have been identified (Figure 2). These mutations all seem to show an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance.103 A mutation in TARDBP has also been linked to two cases of FTLD–MND. One of these individuals presented with behavioral impairment, while the other presented with language impairment. In both cases, motor symptoms developed 2 years after disease onset.104 Interestingly, the TARBDP mutation found in these FTLD–MND cases (causing a substitution of glycine with serine at amino acid 295) had previously been described in two patients with ALS who had displayed no apparent cognitive impairment.100,101 Finally, a TARDBP missense mutation has now been described in one patient with sporadic FTLD-TDP, who presented with behavioral impairment but no clinical signs of MND.105 Whether further reports of TARDBP mutations in FTLD without MND will emerge remains to be seen. Of note, 31 of the TARDBP mutations described to date reside within the glycine-rich domain of TDP-43.

The genetic evidence suggests that dysfunction of TDP-43 is sufficient to cause both ALS and FTLD-TDP. Moreover, the clustering of mutations within the glycine-rich domain points to an important role for this domain in disease pathogenesis, although efforts to recapitulate features of pathological TDP-43 with point mutation models have yielded mixed results.106

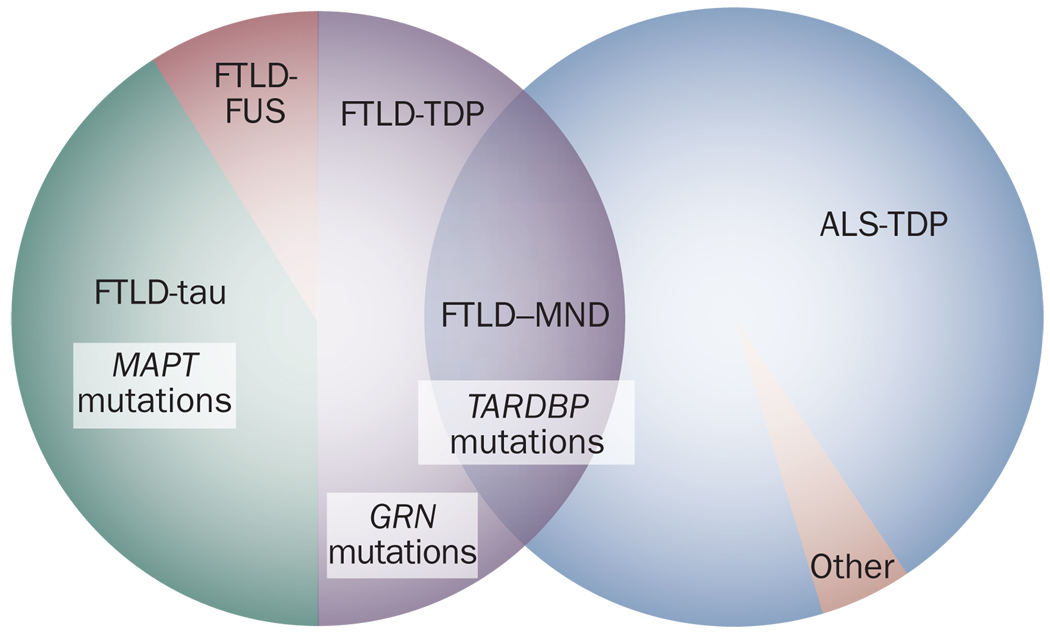

Taken together, the differences between TDP-43 under physiological conditions and disease-associated TDP-43, the similarities between TDP-43 and other proteins implicated in MND, and the TARDBP mutations in FTLD-TDP and in ALS argue strongly for a pathogenic role for TDP-43 in the development of these diseases. Moreover, the fact that the same genetic mutation can cause both ALS and FTLD-TDP suggests that these two clinical entities might be considered as two ends of a spectrum of TDP-43 proteinopathies (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

TDP-43 in FTLD and ALS. Approximately 50% of cases of clinical FTLD exhibit TDP-43 pathology, with the remainder characterized by either tau pathology or other forms of neuropathology, notably FUS inclusions. TDP-43 pathology is observed in the vast majority of ALS cases. In addition, overlap syndromes between FTLD and ALS (for example, FTLD–MND) most frequently show TDP-43 pathology. A subset of individuals with FTLD-tau have mutations in MAPT, while some FTLD-TDP cases are associated with mutations in GRN. Mutations in TARDBP can be found in FTLD-TDP FTLD–MND and ALS, although the vast majority of these mutations manifest clinically as ALS. Abbreviations: ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ALS-TDP, ALS with TDP-43-positive inclusions; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; FTLD-FUS, FTLD with FUS-positive inclusions; FTLD–MND, FTLD with motor neuron disease; FTLD-tau, FTLD with tau-positive inclusions; FTLD-TDP FTLD with TDP-43-positive inclusions; TDP-43, TAR DNA-binding protein 43.

Relevance to clinical practice

The discovery, in 2006, of TDP-43 as the disease-associated protein in FTLD-TDP and ALS opened up many avenues of research into these neurodegenerative diseases. Here we discuss how the findings from this research might influence the future diagnosis, treatment and management of patients with TDP-43 proteinopathies.

One theme that emerges from consideration of the studies covered in this Review is that TDP-43 proteinopathies are clinically heterogeneous. Patients who have underlying TDP-43 abnormalities can present clinically with MND, cognitive impairment, aphasia, or various combinations of the above. Indeed, family members with the same TDP-43-associated disease-causing mutation can present differently from one another.13,104 Should one conclude, therefore, that the further understanding of TDP-43 is useful to neuropathologists but not to neurologists? We argue that the answer is a resounding no.

Certain statements can already be made that might be of potential benefit to living patients with ALS. First, one can assume that most cases of ALS, and especially cases of sporadic ALS, have underlying TDP-43 neuropathology. Thus, trials of therapeutic agents directed at TDP-43 will be of considerable interest to ALS clinicians and families. Second, until recently, the presence of cognitive impairment was considered to be a definitive exclusionary criterion for the diagnosis of ALS.107 Even now, the jury is out on whether cases of otherwise classic upper and lower MND plus some degree of cognitive impairment should be called ALS, although efforts are underway to revise ALS diagnostic criteria to take into account cognitive signs and symptoms.108 Partly spurred on by the developing understanding of the role of TDP-43 in FTLD-TDP and ALS, a number of studies have investigated the presence of cognitive impairment in ALS. One study showed that some degree of cognitive impairment was present in a substantial proportion of ALS cases,19 while another study showed that such deficits were found in the majority of patients with this disease.109 With the dramatic advances in TDP-43-related research, cognitive impairment in ALS now has a neuropathological and mechanistic basis, and we and others have argued that ALS and FTLD might be considered to be two phenotypic manifestations of one underlying pathogenic process.63,74,110 The practical implication of this largely nosological argument is that ALS clinicians should assess the cognitive function of their patients, since deficits in cognition are likely to affect a substantial proportion of people with this MND.

For clinicians treating the FTLD end of the TDP-43 spectrum, the most relevant lesson from research into TDP-43 is probably that ≈90% of patients with FTLD fall into one of two equally prevalent pathological classes: FTLD-tau or FTLD-TDP.111 TDP-43 provides a unifying positive feature, and possible shared etiology, for a patient group (individuals with FTLD-U) that until recently might have been considered to comprise a mixture of various disease entities. This point is relevant to the design of clinical trials, in which estimates of heterogeneity in the treated population are needed to calculate the number of patients needed to see a given effect size.

Finally, while efforts to develop TDP-43-based biomarkers are at a very early stage, the initial studies of TDP-43 in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid offer promise that informative biomarkers for primary and secondary TDP-43 proteinopathies will soon be available.112–114 Such biomarkers might facilitate diagnosis of these disorders by clinicians, and contribute to the design of clinical trials of disease-modifying therapies.

Conclusions

The discovery of TDP-43 in the ubiquitinated inclusions of FTLD-TDP and ALS, along with subsequent work characterizing both the normal functions of TDP-43 and the potential role of this protein in disease pathogenesis, has been an important chapter in a century-long effort to understand the etiologies of FTLD and MND. The identification of TDP-43 as a disease-associated protein now puts a ‘molecular face’ on the inclusions found in ALS, FTLD-TDP, overlap cases, and related disorders. Furthermore, the neuropathological and genetic findings for TDP-43 open up exciting new opportunities to improve the diagnosis and treatment of these disorders.

Many parallels exist between events in TDP-43-related research and prior work on the roles of Aβ and tau in AD, α-synuclein in PD, and tau in FTLD-tau. A striking aspect of TDP-43-related research, which is not shared with research into these other pathogenic proteins, is the remarkable pace at which the field has developed. Indeed, although tau was first implicated as a component of neurofibrillary tangles in AD by Brion and colleagues in 1985,115,116 6 years passed before tau was proven to be the building block of the paired helical filaments that form such tangles.117 The first reports of tau as a cerebrospinal fluid biomarker for AD did not appear until 1995,118,119 and another 3 years elapsed before mutations in MAPT were discovered to cause familial FTLD-tau.11,12 Tau transgenic mice with a neurodegenerative phenotype were reported in 1999;120 however, proof of concept studies demonstrating that tau-focused therapies could ameliorate tau-mediated neurodegeneration did not emerge until 2005.121

Given the intense interest in TDP-43, multiple animal models of TDP-43 proteinopathies will probably emerge in the coming year. Indeed, the first report of an ALS mutation-bearing TDP-43 transgenic mouse with neurodegenerative features has already been published.122 Such developments provide optimism that the 20 years that elapsed from the initial implication of tau in AD to a proof of concept drug intervention study in an animal model could well be collapsed into 4–5 years for TDP-43 proteinopathies. Accordingly, as the prospect of molecularly targeted therapies moves closer to the clinic, the hope is that drugs based mechanistically on TDP-43 pathophysiology will slow or reverse the progress of ALS and FTLD-TDP, which are otherwise fatal neurodegenerative diseases.

Review criteria

PubMed was searched for articles using the following terms: “TDP-43”, “TDP43”, “TARDBP”, “amyotrophic lateral sclerosis”, “ALS”, “frontotemporal lobar degeneration”, “FTLD”, “FTLD-U”, “frontotemporal dementia”, “FTD”, “progranulin”, “GRN” and “FUS”. The PubMed searches were not limited by year of publication, although the relatively recent advent of this field meant that most of the papers returned from these searches were published between 1995 and the present day. Only full-text English language papers were reviewed. Relevant articles identified from the reference lists of articles found in the initial search were also reviewed.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Pick A. On the relationship of senile brain atrophy to aphasia [German] Prag. Med. Wochenschr. 1892;17:165–167. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Todman D. Arnold Pick (1851–1924) J. Neurol. 2009;256:504–505. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearce JM. Pick’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2003;74:169. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alzheimer A. Unusual illnesses of late life [German] Z. Ges. Neurol. Psychiatr. 1911;4:356–385. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kertesz A, Hillis A, Munoz DG. Frontotemporal degeneration, Pick’s disease, Pick complex, and Ravel. Ann. Neurol. 2003;54 Suppl. 5:S1–S2. doi: 10.1002/ana.10595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brun A. Identification and characterization of frontal lobe degeneration: historical perspective on the development of FTD. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2007;21:S3–S4. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31815bf511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neary D, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51:1546–1554. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Lund and Manchester Groups. Clinical and neuropathological criteria for frontotemporal dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1994;57:416–418. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.4.416. [No authors listed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forman MS, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: clinicopathological correlations. Ann. Neurol. 2006;59:952–962. doi: 10.1002/ana.20873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKhann GM, et al. Clinical and pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia: report of the work group on frontotemporal dementia and Pick’s disease. Arch. Neurol. 2001;58:1803–1809. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.11.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutton M, et al. Association of missense and 5'-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature. 1998;393:702–705. doi: 10.1038/31508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poorkaj P, et al. Tau is a candidate gene for chromosome 17 frontotemporal dementia. Ann. Neurol. 1998;43:815–825. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cruts M, et al. Null mutations in progranulin cause ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17q21. Nature. 2006;442:920–924. doi: 10.1038/nature05017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker M, et al. Mutations in progranulin cause tau-negative frontotemporal dementia linked to chromosome 17. Nature. 2006;442:916–919. doi: 10.1038/nature05016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neumann M, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackenzie IR, et al. Nomenclature for neuropathologic subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus recommendations. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:15–18. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0460-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cairns NJ, et al. TDP-43 in familial and sporadic frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin inclusions. Am. J. Pathol. 2007;171:227–240. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodges JR, et al. Clinicopathological correlates in frontotemporal dementia. Ann. Neurol. 2004;56:399–406. doi: 10.1002/ana.20203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lomen-Hoerth C, et al. Are amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients cognitively normal? Neurology. 2003;60:1094–1097. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055861.95202.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talbot K, Ansorge O. Recent advances in the genetics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: common pathways in neurodegenerative disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15:R182–R187. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang IF, Reddy NM, Shen CK. Higher order arrangement of the eukaryotic nuclear bodies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:13583–13588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212483099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winton MJ, et al. Disturbance of nuclear and cytoplasmic TAR DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) induces disease-like redistribution, sequestration, and aggregate formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:13302–13309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800342200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayala YM, et al. Structural determinants of the cellular localization and shuttling of TDP-43. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:3778–3785. doi: 10.1242/jcs.038950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ou SH, Wu F, Harrich D, Garcia-Martinez LF, Gaynor RB. Cloning and characterization of a novel cellular protein, TDP-43, that binds to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 TAR DNA sequence motifs. J. Virol. 1995;69:3584–3596. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3584-3596.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buratti E, et al. Nuclear factor TDP-43 and SR proteins promote in vitro and in vivo CFTR exon 9 skipping. EMBO J. 2001;20:1774–1784. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buratti E, Baralle FE. Characterization and functional implications of the RNA binding properties of nuclear factor TDP-43, a novel splicing regulator of CFTR exon 9. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:36337–36343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acharya KK, Govind CK, Shore AN, Stoler MH, Reddi PP. cis-Requirement for the maintenance of round spermatid-specific transcription. Dev. Biol. 2006;295:781–790. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abhyankar MM, Urekar C, Reddi PP. A novel CpG-free vertebrate insulator silences the testis-specific SP-10 gene in somatic tissues: role for TDP-43 in insulator function. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:36143–36154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ayala YM, Pagani F, Baralle FE. TDP43 depletion rescues aberrant CFTR exon 9 skipping. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1339–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buratti E, Brindisi A, Pagani F, Baralle FE. Nuclear factor TDP-43 binds to the polymorphic TG repeats in CFTR intron 8 and causes skipping of exon 9: a functional link with disease penetrance. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;74:1322–1325. doi: 10.1086/420978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mercado PA, Ayala YM, Romano M, Buratti E, Baralle FE. Depletion of TDP 43 overrides the need for exonic and intronic splicing enhancers in the human apoA-II gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6000–6010. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang HY, Wang IF, Bose J, Shen CK. Structural diversity and functional implications of the eukaryotic TDP gene family. Genomics. 2004;83:130–139. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strong MJ, et al. TDP43 is a human low molecular weight neurofilament (hNFL) mRNA-binding protein. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2007;35:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ayala YM, Misteli T, Baralle FE. TDP-43 regulates retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation through the repression of cyclin-dependent kinase 6 expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:3785–3789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800546105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dreyfuss G, Matunis MJ, Piñol-Roma S, Burd CG. hnRNP proteins and the biogenesis of mRNA. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1993;62:289–321. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He Y, Smith R. Nuclear functions of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins A/B. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009;66:1239–1256. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8532-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ayala YM, et al. HumanDrosophila C elegans TDP43: nucleic acid binding properties and splicing regulatory function. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;348:575–588. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buratti E, et al. TDP-43 binds heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A/B through its C-terminal tail: an important region for the inhibition of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator exon 9 splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:37572–37584. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arai T, et al. TDP-43 is a component of ubiquitin-positive tau-negative inclusions in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;351:602–611. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brandmeir NJ, et al. Severe subcortical TDP-43 pathology in sporadic frontotemporal lobar degeneration with motor neuron disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115:123–131. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davidson Y, et al. Ubiquitinated pathological lesions in frontotemporal lobar degeneration contain the TAR DNA-binding protein, TDP-43. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;113:521–533. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0189-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geser F, et al. Clinical and pathological continuum of multisystem TDP-43 proteinopathies. Arch. Neurol. 2009;66:180–189. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sampathu DM, et al. Pathological heterogeneity of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions delineated by ubiquitin immunohistochemistry and novel monoclonal antibodies. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;169:1343–1352. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mackenzie IR, et al. The neuropathology of frontotemporal lobar degeneration caused by mutations in the progranulin gene. Brain. 2006;129:3081–3090. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Josephs KA, et al. Neuropathologic features of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions with progranulin gene (PGRN) mutations. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2007;66:142–151. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31803020cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neumann M, et al. A new subtype of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with FUS pathology. Brain. 2009;132:2922–2931. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kwiatkowski TJ, Jr, et al. Mutations in the FUS/TLS gene on chromosome 16 cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2009;323:1205–1208. doi: 10.1126/science.1166066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vance C, et al. Mutations in FUS, an RNA processing protein, cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis type 6. Science. 2009;323:1208–1211. doi: 10.1126/science.1165942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Corrado L, et al. Mutations of FUS gene in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Med. Genet. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.071027. doi:10.1136/jmg.2009.071027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Belzil VV, et al. Mutations in FUS cause FALS and SALS in French and French Canadian populations. Neurology. 2009;73:1176–1179. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bbfeef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dickson DW, Josephs KA, Amador-Ortiz C. TDP-43 in differential diagnosis of motor neuron disorders. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:71–79. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Geser F, et al. Evidence of multisystem disorder in whole-brain map of pathological TDP-43 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:636–641. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.5.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCluskey LF, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-plus syndrome with TAR DNA-binding protein-43 pathology. Arch. Neurol. 2009;66:121–124. doi: 10.1001/archneur.66.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mackenzie IR, et al. Pathological TDP-43 distinguishes sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with SOD1 mutations. Ann. Neurol. 2007;61:427–434. doi: 10.1002/ana.21147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watts GD, et al. Inclusion body myopathy associated with Paget disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia is caused by mutant valosin-containing protein. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:377–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guinto JB, Ritson GP, Taylor JP, Forman MS. Valosin-containing protein and the pathogenesis of frontotemporal dementia associated with inclusion body myopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:55–61. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weihl CC, et al. TDP-43 accumulation in inclusion body myopathy muscle suggests a common pathogenic mechanism with frontotemporal dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2008;79:1186–1189. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.131334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Greenberg SA, Watts GD, Kimonis VE, Amato AA, Pinkus JL. Nuclear localization of valosin-containing protein in normal muscle and muscle affected by inclusion-body myositis. Muscle Nerve. 2007;36:447–454. doi: 10.1002/mus.20823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wider C, et al. Pallidonigral TDP-43 pathology in Perry syndrome. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2009;15:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Farrer MJ, et al. DCTN1 mutations in Perry syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:163–165. doi: 10.1038/ng.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Puls I, et al. Mutant dynactin in motor neuron disease. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:455–466. doi: 10.1038/ng1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Munch C, et al. Heterozygous R1101K mutation of the DCTN1 gene in a family with ALS and FTD. Ann. Neurol. 2005;58:777–780. doi: 10.1002/ana.20631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Geser F, Martinez-Lage M, Kwong LK, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia and beyond: the TDP-43 diseases. J. Neurol. 2009;256:1205–1214. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5069-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hasegawa M, et al. TDP-43 is deposited in the Guam parkinsonism-dementia complex brains. Brain. 2007;130:1386–1394. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Geser F, et al. Pathological TDP-43 in parkinsonism-dementia complex and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis of Guam. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115:133–145. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0257-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Amador-Ortiz C, et al. TDP-43 immunoreactivity in hippocampal sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 2007;61:435–445. doi: 10.1002/ana.21154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arai T, et al. Phosphorylated TDP-43 in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:125–136. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0480-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Higashi S, et al. Concurrence of TDP-43, tau and α-synuclein pathology in brains of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain Res. 2007;1184:284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hu WT, et al. Temporal lobar predominance of TDP-43 neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions in Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:215–220. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0400-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Uryu K, et al. Concomitant TAR-DNA-binding protein 43 pathology is present in Alzheimer disease and corticobasal degeneration but not in other tauopathies. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2008;67:555–564. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31817713b5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nakashima-Yasuda H, et al. Co-morbidity of TDP-43 proteinopathy in Lewy body related diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:221–229. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schwab C, Arai T, Hasegawa M, Yu S, McGeer PL. Colocalization of transactivation-responsive DNA-binding protein 43 and huntingtin in inclusions of Huntington disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2008;67:1159–1165. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31818e8951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rothstein JD. TDP-43 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: pathophysiology or patho-babel? Ann. Neurol. 2007;61:382–384. doi: 10.1002/ana.21155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kwong LK, Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. TDP-43 proteinopathy: the neuropathology underlying major forms of sporadic and familial frontotemporal lobar degeneration and motor neuron disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:63–70. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Buratti E, Baralle FE. Multiple roles of TDP-43 in gene expression, splicing regulation, and human disease. Front. Biosci. 2008;13:867–878. doi: 10.2741/2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Neumann M, Tolnay M, Mackenzie IR. The molecular basis of frontotemporal dementia. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2009;11:e23. doi: 10.1017/S1462399409001136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hasegawa M, et al. Phosphorylated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2008;64:60–70. doi: 10.1002/ana.21425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Inukai Y, et al. Abnormal phosphorylation of Ser409/410 of TDP-43 in FTLD-U and ALS. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2899–2904. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Neumann M, et al. Phosphorylation of S409/410 of TDP-43 is a consistent feature in all sporadic and familial forms of TDP-43 proteinopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:137–149. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0477-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ballatore C, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Tau-mediated neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:663–672. doi: 10.1038/nrn2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Igaz LM, et al. Expression of TDP-43 C-terminal fragments in vitro recapitulates pathological features of TDP-43 proteinopathies. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:8516–8524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809462200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Johnson BS, McCaffery JM, Lindquist S, Gitler AD. A yeast TDP-43 proteinopathy model: exploring the molecular determinants of TDP-43 aggregation and cellular toxicity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:6439–6444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802082105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang YJ, et al. Aberrant cleavage of TDP-43 enhances aggregation and cellular toxicity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:7607–7612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900688106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nonaka T, Kametani F, Arai T, Akiyama H, Hasegawa M. Truncation and pathogenic mutations facilitate the formation of intracellular aggregates of TDP-43. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:3353–3364. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Igaz LM, et al. Enrichment of C-terminal fragments in TAR DNA-binding protein-43 cytoplasmic inclusions in brain but not in spinal cord of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2008;173:182–194. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen-Plotkin AS, et al. Variations in the progranulin gene affect global gene expression in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:1349–1362. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lefebvre S, et al. Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell. 1995;80:155–165. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Battle DJ, et al. The SMN complex: an assembly machine for RNPs. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2006;71:313–320. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lagier-Tourenne C, Cleveland DW. Rethinking ALS: the FUS about TDP-43. Cell. 2009;136:1001–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Janknecht R. EWS-ETS oncoproteins: the linchpins of Ewing tumors. Gene. 2005;363:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gitcho MA, et al. TDP-43 A315T mutation in familial motor neuron disease. Ann. Neurol. 2008;63:535–538. doi: 10.1002/ana.21344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sreedharan J, et al. TDP-43 mutations in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2008;319:1668–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.1154584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kabashi E, et al. TARDBP mutations in individuals with sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:572–574. doi: 10.1038/ng.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Van Deerlin VM, et al. TARDBP mutations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with TDP-43 neuropathology: a genetic and histopathological analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:409–416. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70071-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kamada M, et al. Screening for TARDBP mutations in Japanese familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009;284:69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kuhnlein P, et al. Two German kindreds with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis due to TARDBP mutations. Arch. Neurol. 2008;65:1185–1189. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.9.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Daoud H, et al. Contribution of TARDBP mutations to sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Med. Genet. 2009;46:112–114. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.062463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yokoseki A, et al. TDP-43 mutation in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2008;63:538–542. doi: 10.1002/ana.21392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rutherford NJ, et al. Novel mutations in TARDBP (TDP-43) in patients with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Corrado L, et al. High frequency of TARDBP gene mutations in Italian patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Mutat. 2009;30:688–694. doi: 10.1002/humu.20950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Del Bo R, et al. TARDBP (TDP-43) sequence analysis in patients with familial and sporadic ALS: identification of two novel mutations. Eur. J. Neurol. 2009;16:727–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Baumer D, Parkinson N, Talbot K. TARDBP in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: identification of a novel variant but absence of copy number variation. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2009;80:1283–1285. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.166512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pesiridis GS, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Mutations in TDP-43 link glycine-rich domain functions to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:R156–R162. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Benajiba L, et al. TARDBP mutations in motoneuron disease with frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Ann. Neurol. 2009;65:470–473. doi: 10.1002/ana.21612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kovacs GG, et al. TARDBP variation associated with frontotemporal dementia, supranuclear gaze palsy, and chorea. Mov. Disord. 2009;24:1843–1847. doi: 10.1002/mds.22697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.D’Ambrogio A, et al. Functional mapping of the interaction between TDP-43 and hnRNP A2 in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4116–4126. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2000;1:293–299. doi: 10.1080/146608200300079536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Strong MJ, et al. Consensus criteria for the diagnosis of frontotemporal cognitive and behavioural syndromes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2009;10:131–146. doi: 10.1080/17482960802654364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Murphy JM, et al. Continuum of frontal lobe impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch. Neurol. 2007;64:530–534. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.4.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Forman MS, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. TDP-43: a novel neurodegenerative proteinopathy. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2007;17:548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mackenzie IR, et al. Nomenclature for neuropathologic subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus recommendations. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:15–18. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0460-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Foulds P, et al. TDP-43 protein in plasma may index TDP-43 brain pathology in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:141–146. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0389-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Steinacker P, et al. TDP-43 in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch. Neurol. 2008;65:1481–1487. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kasai T, et al. Increased TDP-43 protein in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:55–62. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Progress from Alzheimer’s tangles to pathological tau points towards more effective therapies now. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:257–262. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9s328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Brion JPH, Nunez J, Flament-Durand J. Immunological evidence that tau protein forms the degenerative neurofibrillary lesions in Alzheimer’s disease [French] Arch. Biol. 1985;95:229–235. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lee VM, Balin BJ, Otvos L, Jr, Trojanowski JQ. A68: a major subunit of paired helical filaments and derivatized forms of normal tau. Science. 1991;251:675–678. doi: 10.1126/science.1899488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nitsch RM, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of amyloid β-protein in Alzheimer’s disease: inverse correlation with severity of dementia and effect of apolipoprotein E genotype. Ann. Neurol. 1995;37:512–518. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Vigo-Pelfrey C, et al. Elevation of microtubule-associated protein tau in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1995;45:788–793. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.4.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ishihara T, et al. Age-dependent emergence and progression of a tauopathy in transgenic mice overexpressing the shortest human tau isoform. Neuron. 1999;24:751–762. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Zhang B, et al. Microtubule-binding drugs offset tau sequestration by stabilizing microtubules and reversing fast axonal transport deficits in a tauopathy model. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:227–231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406361102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wegorzewska I, Bell S, Cairns NJ, Miller TM, Baloh RH. TDP-43 mutant transgenic mice develop features of ALS and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:18809–18814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908767106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]