Abstract

The blue part of the light spectrum has been associated with leaf characteristics which also develop under high irradiances. In this study blue light dose–response curves were made for the photosynthetic properties and related developmental characteristics of cucumber leaves that were grown at an equal irradiance under seven different combinations of red and blue light provided by light-emitting diodes. Only the leaves developed under red light alone (0% blue) displayed dysfunctional photosynthetic operation, characterized by a suboptimal and heterogeneously distributed dark-adapted Fv/Fm, a stomatal conductance unresponsive to irradiance, and a relatively low light-limited quantum yield for CO2 fixation. Only 7% blue light was sufficient to prevent any overt dysfunctional photosynthesis, which can be considered a qualitatively blue light effect. The photosynthetic capacity (Amax) was twice as high for leaves grown at 7% blue compared with 0% blue, and continued to increase with increasing blue percentage during growth measured up to 50% blue. At 100% blue, Amax was lower but photosynthetic functioning was normal. The increase in Amax with blue percentage (0–50%) was associated with an increase in leaf mass per unit leaf area (LMA), nitrogen (N) content per area, chlorophyll (Chl) content per area, and stomatal conductance. Above 15% blue, the parameters Amax, LMA, Chl content, photosynthetic N use efficiency, and the Chl:N ratio had a comparable relationship as reported for leaf responses to irradiance intensity. It is concluded that blue light during growth is qualitatively required for normal photosynthetic functioning and quantitatively mediates leaf responses resembling those to irradiance intensity.

Keywords: Blue light, chlorophyll fluorescence imaging, cucumber (Cucumis sativus), dose–response curves, leaf mass per unit leaf area (LMA), light-emitting diodes (LEDs), photoinhibition, photosynthetic capacity, red light, starch accumulation

Introduction

Plant development and physiology are strongly influenced by the light spectrum of the growth environment. The underlying mechanisms of the effect of different growth spectra on plant development are not known in detail, although the involvement of photoreceptors has been demonstrated for a wide range of spectrum-dependent plant responses. Cryptochromes and phototropins are specifically blue light sensitive, whereas phytochromes are more sensitive to red than to blue (Whitelam and Halliday, 2007). Blue light is involved in a wide range of plant processes such as phototropism, photomorphogenesis, stomatal opening, and leaf photosynthetic functioning (Whitelam and Halliday, 2007). At the chloroplast level, blue light has been associated with the expression of ‘sun-type’ characteristics such as a high photosynthetic capacity (Lichtenthaler et al., 1980). Most studies assessing blue light effects on the leaf- or whole-plant level have either compared responses to a broad-band light source with responses to blue-deficient light (e.g. Britz and Sager, 1990; Matsuda et al., 2008), or compared plants grown under blue or a combination of red and blue light with plants grown under red light alone (e.g. Brown et al., 1995; Bukhov et al., 1995; Yorio, 2001; Matsuda et al., 2004; Ohashi et al, 2006). Overall there is a trend to higher biomass production and photosynthetic capacity in a blue light-containing irradiance. Before the development of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) that were intense enough to be used for experimental plant cultivation (Tennessen et al., 1994), light sources emitting wavelengths in a broader range than strictly the red (i.e. 600–700 nm) or blue (i.e. 400–500 nm) region were often used (e.g. Voskresenskaya et al., 1977). Other wavelengths can interact with blue light responses. For example, green light has been reported to antagonize some blue light responses, such as stomatal opening and inhibition of hypocotyl elongation in seedlings (Folta and Maruhnich, 2007). The blue light enhancement effect on photosynthetic capacity appears to be greater when using combinations of red and blue light produced by LEDs than when broad-band light is made deficient in blue by a filter (e.g. for spinach compare Matsuda et al., 2007 and 2008). This raises the question of whether plants exposed to red light alone suffer a spectral ‘deficiency’ syndrome, which may be reversed by blue light as well as by longer wavelengths.

Poorter et al. (2010) stress the importance of dose–response curves for quantitative analysis of the effects of environmental factors on plant phenotypes, allowing a better understanding of plant–environment interactions than the comparison of two treatments only. It is not clear whether the enhancement effect of blue light on leaf photosynthetic capacity is a qualitative threshold response or a quantitative progressive response, or a combination of both. Only few specific processes in leaves have been identified as quantitative blue light responses, such as chloroplast movement (Jarillo et al., 2001) and stomatal conductance (Sharkey and Raschke, 1981). Matsuda et al. (2007) found a higher photosynthetic capacity for spinach leaves grown under 300 μmol m−2 s−1 mixed red/blue irradiance containing 30 μmol m−2 s−1 blue than for leaves grown under red alone. A higher blue light fraction did not yield a significant further enhancement in light-saturated assimilation (Amax), which may be interpreted as a qualitative blue light effect. However, a quantitative blue light effect at quantum fluxes <30 μmol m−2 s−1 cannot be excluded.

A diverse choice of LEDs powerful enough for use as a growth irradiance source in controlled environments has recently become available (e.g. Massa et al., 2008). These LEDs allow the effect of light quality to be investigated independently of the amount of photosynthetic irradiance. LED illumination has been used here to study the response curves of a range of parameters related to leaf photosynthesis of plants that were grown at an irradiance with a proportion of blue light ranging from 0% to 100%. A range of other leaf characteristics important for the functioning of photosynthesis, such as stomatal development and behaviour, leaf mass per area (LMA), and the content of N, pigments, and carbohydrates, were also determined. The spectra and the extent of variation in the ratio of red and blue irradiance that can be achieved with LED lighting are dissimilar to field conditions. However, the responses of leaves to these unnatural environments provides the possibility to unravel the complex developmental and functional interactions that normally occur in the natural light environment.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Cucumber plants (Cucumis sativus cv. Hoffmann's Giganta) were sown in vermiculite and germinated under 100 μmol m−2 s−1 cool white fluorescent lamps (TLD 50 W 840 HF, Philips, The Netherlands) in a climate chamber. After 1 week, when the cotyledons had just opened, the seedlings were transferred to a hydroponic system (Hoagland's solution, pH=5.9±0.2; EC=1.2 mScm−1) in a climate chamber. The day/night temperature was 25 °C/23 °C, the relative humidity was 70%, and the CO2 concentration was ambient. All plants were subjected to 100±5 μmol m−2 s−1 irradiance (16 h/8 h day/night) provided by a mixture of blue and red LEDs with dominant wavelengths of 450 nm and 638 nm, respectively (types Royal Blue and Red Luxeon K2, Lumileds Lighting Company, San Jose, CA, USA). The LEDs were equipped with lenses (6 º exit angle) and the arrays were suspended ∼1 m above the plants, so irradiance from the two LED types was well mixed. The lenses ensured that small differences in leaf height had only minor effects on the irradiance received. The seven different spectral treatments are expressed as the blue (B) light percentage: 0B, 7B, 15B, 22B, 30B, 50B, and 100B; the remaining percentage was red. Irradiance was measured routinely using a quantum sensor (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA), but was also verified with a spectroradiometer (USB2000 spectrometer, Ocean Optics, Duiven, The Netherlands, calibrated against a standard light source). The difference in irradiance measured with the two devices was <2% for the spectra used.

The plants were allowed to grow until the second leaf was fully mature (17–22 d after planting the seedlings) when it could be used for photosynthesis measurements. If necessary, the second leaf, which was the leaf used for all measurements, was supported in a horizontal position during growth to ensure that it received the specified irradiance.

Stomata analysis

The stomatal conductance (gsw) was measured on three positions on each leaf surface using a leaf porometer (model SC-1, Decagon Devices, Inc., Pullman, WA, USA) prior to the gas exchange measurements (see below). The ratio of the average gsw of the abaxial and adaxial leaf surface (gsw ratio) was used in the calculations of the gas exchange parameters (n=6). Additionally, silicon rubber impressions were made (see Smith et al., 1989) on both the adaxial and abaxial surface of the leaves grown under 0B, 15B, 30B, and 50B (n ≥3). Stomatal density, length, and aperture were determined from images of the impressions using the procedure described in Nejad and van Meeteren (2005).

Leaf gas exchange and fluorescence measurements

Gas exchange and chlorophyll (Chl) fluorescence were measured using a custom-made leaf chamber within which 4.52 cm2 of leaf surface was illuminated. A LI-7000 CO2/H2O gas analyser (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) measured the CO2 and H2O exchange of the leaf and ambient atmospheric pressure. Leaf temperature was monitored by a thermocouple pressed against the abaxial leaf surface. A custom-made measuring-light source comprised of independently controllable red and blue LEDs with attached lenses, emitting a spectrum similar to that of the LEDs used for growth-light, was used to provide the required red/blue combination in the irradiance range 0–1700 μmol m−2 s−1. A polished steel reflector in the form of an inverted truncated cone (i.e. the inlet to the reflector was larger than the outlet) allowed the irradiance to be well mixed and equally distributed over the leaf surface. The gas mix used contained 380 μmol mol−1 CO2, 20.8±0.4 mmol mol−1 H2O, and either 210 mmol mol−1 or 20 mmol mol−1 O2 (ambient O2 or low O2), dependent on the type of measurement. A flow rate of 200–700 ml min−1 was used, depending on the CO2 depletion which ranged from 18 μmol mol−1 to 26 μmol mol−1 at saturating irradiance. The equations developed by von Caemmerer and Farquhar (1981) were used to calculate assimilation, gsw, and the CO2 concentration in the substomatal cavity of the leaf relative to that in the leaf chamber air (Ci Ca−1) from the gas exchange data. The boundary layer resistance of both leaf surfaces in the leaf chamber during gas exchange measurements was estimated using the method of Jarvis (1971). Chl fluorescence was measured using a PAM 101 Chl fluorometer with an emitter detector unit (model 101 ED; Heinz Walz, Effeltrich, Germany). The modulated red measuring-light intensity was <0.5 μmol m−2 s−1. A 250 W quartz–halogen lamp connected to an additional optical fibre provided a saturating light pulse (7500 μmol m−2 s−1) to allow measurement of the Fm or Fm′ relative fluorescence yield (Baker et al., 2007). The fibres were fixed ∼4 cm above the leaf chamber at such an angle that they did not interfere with the actinic light beam.

Irradiance–response curves were measured on fully expanded second leaves, and each growth-light treatment was performed twice. As there were no significant differences between the two repetitions, the individual plants from the two repetitions were treated as independent repetitions (n=6) in the analysis. An ambient O2 concentration was used for these measurements. After clamping a leaf in the leaf chamber, it was dark adapted for 30 min, and dark respiration (Rdark) and the dark-adapted Fv/Fm (Baker et al., 2007) were measured. The irradiance–response curve was measured using a spectrum identical to that under which the plants were grown, using 14 intensities in the range 0–1700 μmol m−2 s−1. The leaves were subjected to each irradiance for at least 20 min, when steady-state assimilation was amply reached. The highest irradiances were omitted if CO2 fixation clearly became light-saturated at lower irradiances. At an irradiance of 100 μmol m−2 s−1, which is equal to the irradiance during growth, the relative quantum yield of photosystem II (PSII) electron transport (ΦPSII) was measured using the method of Genty et al. (1989). After measuring the irradiance–response curve, the plant was left overnight in the dark in a climate room and the following day samples were taken from the measured leaf in order to measure the light absorptance spectrum, leaf mass per area (LMA), and pigment- and N-content (see below).

In order to assess the possibility that Ci was limiting assimilation at low irradiance, the relationship between assimilation and electron transport rate (ETR) was investigated in more detail. Under photorespiratory conditions a lower assimilation per unit ETR is expected for a leaf with a Ci that is limiting for assimilation than for a leaf with no limiting Ci. Under non-photorespiratory conditions no difference is to be expected (Harbinson et al., 1990). Additional gas exchange and fluorescence measurements were made on leaves grown under 0B and 30B using seven different incident irradiances (0–100 μmol m−2 s−1) and both ambient and low O2 (n=3). Chl fluorescence measurements were made at each irradiance to determine ΦPSII once CO2 fixation had stabilized, after which the actinic irradiance was switched off to measure Rdark. Gross assimilation (Agross) was calculated as net assimilation (Anet) plus Rdark, which assumes, as is commonly done, that Rdark is a reasonable estimate of respiration in the light. Light absorptance (see below) was measured directly after measuring the photosynthesis irradiance–response. The product of the absorbed actinic irradiance and ΦPSII serves as an index for ETR (e.g. Kingston-Smith et al., 1997). The distribution of dark-adapted Fv/Fm over these 0B- and 30B-grown leaves was measured by means of Chl fluorescence images. Images of three different leaves from each treatment were made using a PSI Fluorcam 700MF Chl fluorescence imaging system (PSI, Brno, Czech Republic), using the procedure described in Hogewoning and Harbinson (2007).

Measurement of leaf light absorptance

Leaf light absorptance was calculated in 1 nm steps in the range 400–800 nm from measurements of leaf reflectance and transmittance made on 12 leaf discs per leaf. Details of the procedure and measurement system, which consisted of two integrating spheres, each connected to a spectrometer and a custom-made light source, are described in Hogewoning et al. (2010) and Zheng et al. (2010). The integrated absorptance of the actinic measuring irradiance used during gas exchange measurements was subsequently calculated by multiplying the relative leaf absorptance spectrum by the spectrum of the measuring-light.

LMA, nitrogen, pigment, and carbohydrate analysis

From each leaf, 10 leaf discs (1.28 cm2) were cut randomly over the leaf area, avoiding the leaf margins and main veins. The discs were stored at –22 °C, freeze dried, and weighed, and LMA was calculated. After weighing, the C and N contents were determined for all treatments by a C/N analyser (n=5) and the nitrate content was determined for the treatments 0B and 30B (n=4) according to Trouwborst et al. (2010).

An additional eight leaf discs (0.65 cm2) were cut from the same leaf and stored in 10 ml of dimethylformamide (DMF) in the dark at –22 °C. The absorbance of the extract was measured in the range 400–750 nm using a Cary 4000 spectrophotometer (Varian Instruments, Walnut Creek, CA, USA), and the Chl and carotenoid concentrations were calculated using the equations of Wellburn (1994).

The carbohydrate content of leaves grown under 0B, 30B, and 100B was measured by cutting 10–15 discs (1.28 cm2) from one side of the main vein at the end of the photoperiod and 10–15 discs from the other side of the main vein just before the start of the photoperiod (n=4). Soluble carbohydrate and starch concentrations were analysed as described in Hogewoning and Harbinson (2007).

Curve fitting and statistics

The photosynthesis data measured to obtain light–response curves of the leaves grown under different blue/red combinations were fitted with a non-rectangular hyperbola (Thornley, 1976) using the non-linear fitting procedure NLIN in SAS (SAS Institute Inc. 9.1, Cary, NC, USA) in order to determine the light-limited quantum yield for CO2 fixation (α).

Tukey's HSD was used to make post-hoc multiple comparisons among spectral treatment means from significant one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests (P <0.05), and regression analysis was used to test for significant differences (P <0.05) between the slope of the Agross– ΦPSII×absorbed measuring-light relationship using Genstat (release 9.2, Rothamsted Experimental Station, Harpenden, UK).

Results

Leaf photosynthesis

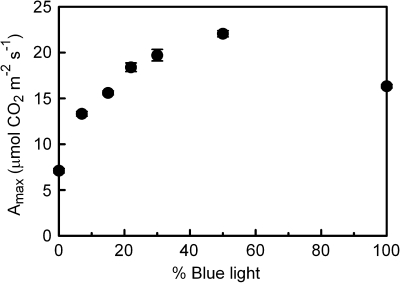

The Amax differed significantly for the leaves grown under different blue (B) light percentages (Fig. 1). Increasing the blue light fraction from 0% to 50% resulted in an increasing Amax, with the greatest increase occurring at the increase from 0% to 7% blue. The 100B-grown leaves had an Amax that was lower than that of the 50B leaves. The light-limited quantum yield for CO2 fixation (α) was lowest for 0B and 100B leaves and highest for the 7B–30B leaves (within this range there was no significant difference in α; Table 1). Dark respiration was lowest for 0B leaves and tended to increase with blue light percentage, except for 100B (Table 1), similar to the pattern found for Amax. The dark-adapted Fv/Fm was typical for an unstressed leaf (i.e. ≥0.8) in all treatments, except 0B, where it was significantly reduced (Table 1). The ΦPSII measured at growth-light intensity (i.e. 100 μmol m−2 s −1) and spectrum was similar for the 15B–100B leaves, but was markedly lower for 0B leaves and slightly, but significantly, lower for 7B leaves.

Fig. 1.

The effect of light quality (the proportion of total PAR that is from the blue rather than from the red part of the spectrum) during growth on the photosynthetic capacity (Amax) of cucumber leaves. Error bars indicate the SEM (n=6).

Table 1.

Different parameters measured or calculated on leaves grown under different light qualities (the proportion of total PAR that is from the blue rather than from the red part of the spectrum).

| Blue light percentage | 0 | 7 | 15 | 22 | 30 | 50 | 100 |

| Fv/Fm | 0.76 b | 0.80 a | 0.80 a | 0.80 a | 0.81 a | 0.81 a | 0.81 a |

| ΦPSII | 0.65 d | 0.74 c | 0.76 b | 0.76 a,b | 0.76 a, b | 0.77 a | 0.76 a,b,c |

| Fv/Fm–ΦPSII | 0.110 a | 0.055 b | 0.044 c | 0.040 c | 0.042 c | 0.034 c | 0.044 b,c |

| Quantum yield CO2 fixation (α) | 0.045 c | 0.052 a,b | 0.053 a | 0.053 a | 0.053 a | 0.048 b,c | 0.045 c |

| Rdark (μmol m−2 s−1) | 0.93 d | 1.17 c | 1.29 a,b,c | 1.39 a,b | 1.27 b,c | 1.45 a | 1.33 a,b,c |

| gsw ratio (abaxial:adaxial) | 2.7 a | 2.6 a | 2.1 a,b | 1.7 b,c | 1.7 b,c | 1.4 c | 1.7 b,c |

| Integrated absorptance | 90.0 d | 92.1 c | 92.4 b,c | 93.1 b,c | 94.0 a,b | 93.7 b | 95.4 a |

| Chl a:b (g g−1) | 3.24 d | 3.36 c | 3.51 a,b | 3.48 a,b | 3.42 b,c | 3.54 a | 3.54 a |

| N (% DW) | 5.7 a | 6.0 a | 5.7 a | 6.0 a | 6.1 a | 6.0 a | 6.2 a |

| C (% DW) | 39.6 a | 38.0 a | 36.8 a | 38.7 a | 37.7 a | 37.6 a | 37.7 a |

| C:N (g g−1) | 6.9 a | 6.4 a,b | 6.5 a,b | 6.4 a,b | 6.2 b | 6.2 b | 6.1 b |

| Chl:N (g g−1) | 5.1 a | 4.3 b,c | 4.6 a,b | 4.1 b,c,d | 4.3 b,c | 3.9 c,d | 3.7 d |

| PSS (phytochromes) | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.51 |

Different letters indicate significant differences (P ≤0.05; n=5 or n=6, no variation for PSS).

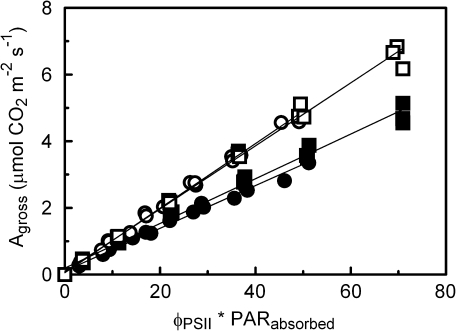

Concerning the more detailed measurements of the photosynthesis irradiance–response between 0 μmol m−2 s −1 and 100 μmol m−2 s −1 incident irradiance on 0B- and 30B-grown leaves, Agross was markedly higher for the low O2 measurements than it was for the ambient O2 measurements (Fig. 2). At all light intensities, ΦPSII was consistently lower for the 0B leaves than it was for the 30B leaves. In both treatments the O2 concentration did not affect ΦPSII (not shown). The absorptance in the green region of the spectrum was 5–10% lower for the 0B- and 100B-grown leaves than for the other treatments, whereas differences in absorptance between the growth-light treatments were negligible for the blue and red region (not shown). Only the red and blue wavelength regions are relevant for integrated absorbed irradiance in this experiment. The integrated absorptance of the growth and measuring-light increased with the percentage of blue light (Table 1), as the blue light was better absorbed than the red light. At both low and ambient O2 concentration there were no significant differences between 0B and 30B for the linear regression between Agross and the product of ΦPSII and the absorbed actinic irradiance (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Relationship between gross CO2 assimilation (Agross) and the product of ΦPSII and the actinic measuring-light absorbed by the leaves, which serves as an index of electron transport (e.g. Kingston-Smith et al., 1997), at an incident irradiance ≤100 μmol m−2 s−1. The cucumber leaves were grown under and also measured with 0B (=100% red; circles) and 30B (squares) irradiance, and gas exchange was measured under low (open symbols) and ambient O2 (filled symbols). Gross assimilation was calculated as dark respiration plus net assimilation. The slopes of the regression lines are significantly different for the two O2 levels (P <0.001), but not for the spectral treatments (P ≥0.23).

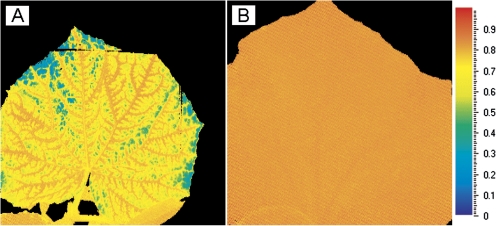

The images of dark-adapted Fv/Fm obtained via Chl fluorescence imaging showed conspicuous differences between the 0B and 30B leaves. Whereas the images from 30B-grown leaves were perfectly homogeneous with an Fv/Fm >0.8, the images of the 0B-grown leaves showed a heterogeneous distribution with dark-adapted Fv/Fm values of ∼0.8 adjacent to the veins and with zones of lower Fv/Fm (typically 0.55–0.70) between the veins (Fig. 3). The 0B leaves also occasionally appeared slightly chlorotic between the veins.

Fig. 3.

Image of the dark-adapted Fv/Fm distribution over an 0B (=100% red; A) and 30B (B) irradiance-grown cucumber leaf. The mixed blue–red-grown leaf (B) has a homogeneous Fv/Fm distribution centred around an Fv/Fm of 0.82, whereas the 0B-grown leaf (A) has a heterogeneous distribution with a high Fv/Fm around the veins and lower values between the veins.

Stomatal effects

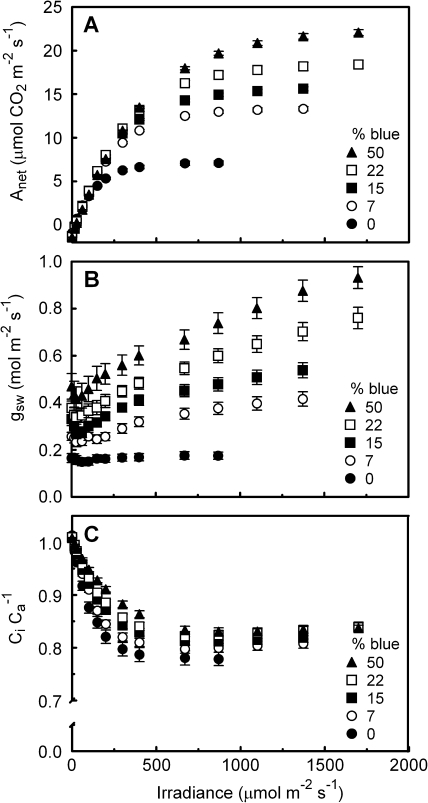

There was a considerable stomatal conductance (gsw) calculated from gas exchange data in the dark-adapted state (Fig. 4B). As the photoperiod of the plants in their growth environment started 1 h before leaves were dark adapted in the leaf chamber, the absence of complete stomatal closure may be due to the diurnal rhythm of the stomata. Also, a significant night-time gsw is not unusual, especially for leaves with a high daytime gsw (Snyder et al., 2003), such as cucumber. Moreover, a substantial night-time gsw has been reported to occur in many horticultural species, and ample water availability (e.g. hydroponics as used here) can increase night-time gsw (Caird et al., 2007). The gsw of leaves grown and measured using 0B was lowest of all the treatments and did not respond to increases in measuring irradiance intensity. Even using 30B or 100B as a measuring irradiance spectrum on the 0B-grown leaves at either 100 μmol m−2 s −1 irradiance or saturating irradiance had no effect on their gsw (data not shown). In all other treatments, gsw increased with increasing irradiance (>100 μmol m−2 s −1). Consistent with the low and constant gsw, the Ci Ca−1 of the 0B-grown leaves decreased more with increasing irradiance than that of the other treatments (Fig. 4C). Data of gsw and Ci Ca−1 for the 30B and 100B leaves are not shown in Fig. 4 due to instrument failure.

Fig. 4.

Response of net assimilation (Anet; A), stomatal conductance (gsw; B), and leaf internal CO2 concentration relative to that of the leaf chamber air (Ci Ca−1; C) to irradiance for cucumber leaves grown under different light qualities (the proportion of total PAR that is from the blue rather than from the red part of the spectrum). The actinic light quality was identical to that during growth. Error bars indicate the SEM (n=6).

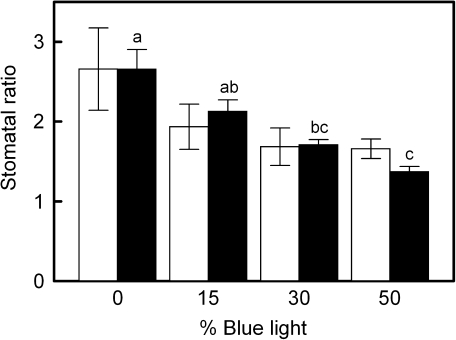

The gsw measured using a porometer also increased with increasing blue light in the growth spectrum (not shown). The ratio of gsw on the abaxial and adaxial leaf surface (gsw ratio) became smaller with an increasing percentage of blue light (Table 1). The stomatal counts on both leaf sides paralleled these results, as the number of stomata on the adaxial leaf surface significantly increased with increasing blue percentage, whereas on the abaxial leaf surface no significant changes were found (not shown), resulting in a decreasing stomatal ratio with increasing blue light (Fig. 5). No significant changes in stomatal length and guard cell width were found for the different treatments (not shown).

Fig. 5.

Ratio of stomatal density (open bars; n ≥3) and stomatal conductance measured with a porometer (filled bars; n=6) for the abaxial and adaxial leaf surface of cucumber leaves grown under different light qualities (the proportion of total PAR that is from the blue rather than from the red part of the spectrum; both parameters are labelled ‘stomatal ratio’ in the plot). Error bars indicate the SEM and letters indicate significant differences (P ≤0.05). No significant differences between the individual means of the stomatal density ratio were found; however, the linear component of the stomatal density ratio–blue light percentage relationship was significant (P=0.04). The decrease in stomatal density ratio with increasing blue light percentage was due to an increasing stomatal density on the adaxial leaf surface.

LMA and nitrogen, pigment, and carbohydrate content

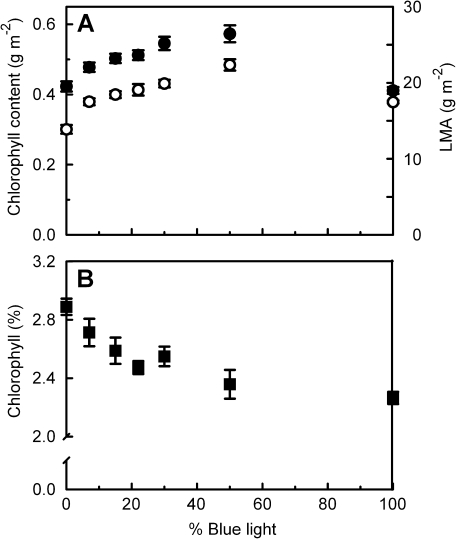

The LMA increased with increasing percentage of blue up to 50% (Fig. 6A). Similar to the Amax–blue percentage relationship (Fig 1), the increase in LMA was relatively greatest when the growth irradiance was changed from 0B to 7B. The total Chl content (Chl a+Chl b; Fig. 6A) and total carotenoid content (not shown) per unit leaf area increased in a similar way to LMA, increasing with percentage blue up to 50%. The Chl a:b ratio was significantly lower for 0B and 7B than at higher blue percentages (Table 1).

Fig. 6.

The effect of light quality (the proportion of total PAR that is from the blue rather than from the red part of the spectrum) during growth on the chlorophyll content per unit leaf area (A, filled symbols, left axis), leaf mass per unit leaf area (LMA; A, open symbols, right axis), and the percentage chlorophyll in the leaf on a dry weight basis (B, squares).

Leaf N content and C content per unit dry weight (DW) did not differ significantly between the treatments (Table 1). When expressed per unit leaf area the N and C content therefore depended on the percentage blue light in a way that was similar to LMA (Fig. 6A). The C:N ratio, however, was significantly higher for the 0B treatment than it was for the 30B, 50B, and 100B treatments. The nitrate part of total leaf N was not significantly different for the 0B and 30B leaves and was only 8.8% and 6.4%, respectively.

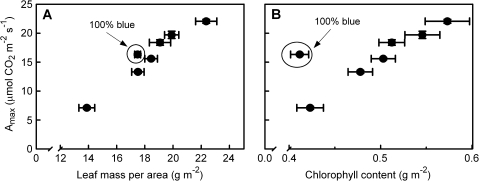

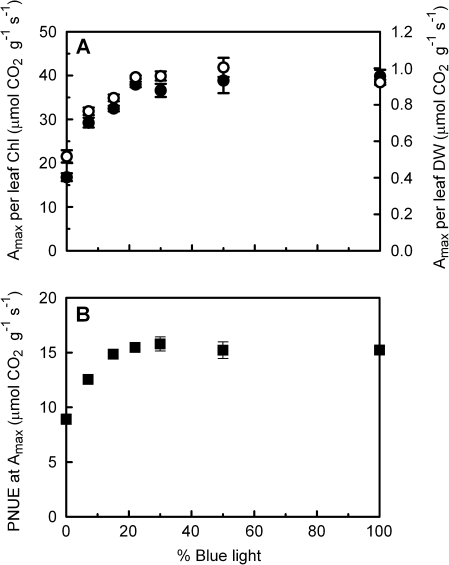

Chl content per unit leaf area correlates well with LMA (Fig. 6A), though there is a small but significant decrease in the Chl content per unit leaf DW as the percentage blue light in the growth irradiance increases (Fig. 6B). For all treatments Amax correlated positively with LMA and Chl content per area leaf, except for Chl content of the 100B leaves (Fig. 7). With an increasing percentage blue light during growth, Amax per unit Chl increases up to 22B, whereas at higher percentages of blue there are no differences between the treatments (Fig. 8A). A similar pattern can be seen for Amax per unit leaf DW (Fig. 8A) and Amax per unit N, which is the photosynthetic N use efficiency (PNUE; Fig. 8B). On a DW basis, the Chl:N ratio decreases significantly with increasing percentage blue (Table 1).

Fig. 7.

Relationship of leaf photosynthetic capacity (Amax) to leaf mass per unit leaf area (A) and chlorophyll content per unit leaf area (B) of cucumber grown under different combinations of red and blue light at an equal irradiance. The order of the values related to the data points corresponds to the blue light percentage under which the leaves were grown, except for the encircled data point which refers to the 100% blue treatment.

Fig. 8.

The effect of light quality (the proportion of total PAR that is from the blue rather than from the red part of the spectrum) during growth of cucumber on leaf photosynthetic capacity (Amax) reached per unit chlorophyll (A, filled symbols, left axis), per unit leaf dry weight (A, open symbols, right axis), and per unit N (B, squares).

The leaf carbohydrate content (on a unit weight basis) was negligibly low at the end of the night period for all treatments (Table 2). At the end of the photoperiod, a considerable amount of carbohydrates, which were mainly comprised of starch and smaller quantities of sucrose, was present in the leaves, with the highest values in the leaves grown under 30B.

Table 2.

Carbohydrate content (mg g−1 DW) of leaves grown under different light qualities (the proportion of total PAR that is from the blue rather than from the red part of the spectrum).

| End dark period |

End photoperiod |

|||||

| Blue % | 0 | 30 | 100 | 0 | 30 | 100 |

| Glucose | 0.4 a | 0.2 a | 0.4 a | 0.5 a | 0.4 a | 0.4 a |

| Sucrose | 0.5 a | 0.3 a | 0.4 a | 8.4 b | 9.6 b | 13.2 a |

| Starch | 1.1 a | 0.6 a | 0.8 a | 45.1 b | 55.8 a | 39.5 b |

Different letters indicate significant differences (P ≤0.05; n=4).

Discussion

Peculiarly, whereas parameters such as Amax, leaf composition, and LMA depended on the percentage of blue light during growth, only the leaves that developed under 0B (100% red light) had a suboptimal Fv/Fm, a low light-limited quantum efficiency for CO2 fixation (α; Table 1), and a stomatal conductance (gsw) that was unresponsive to irradiance (Fig. 4). Such effects on leaves have, to the best of our knowledge, not been reported before and highlight the fundamental difference between leaf adaptation to the growth spectrum and the instantaneous spectral effect on photosynthesis. Instantaneous photosynthetic rates are relatively high when a leaf is illuminated with red light (e.g. McCree, 1972; Inada, 1976).

Disorders in leaf physiology associated with growth under red light alone

A lower photosynthetic rate in plants grown under red light alone has been shown for several crop plants. Matsuda et al. (2004) found a lower photosynthetic rate for rice grown under red LEDs alone than for plants grown under a mixture of red and blue LEDs. Similar results were found for wheat (Goins et al., 1997), which had a lower photosynthesis and DW accumulation when grown under red alone compared with growth under white fluorescent tubes or under red light supplemented with blue. While Yorio et al. (2001) reported a lower DW accumulation in radish, spinach and lettuce grown under red LEDs alone than under white fluorescent tubes or red supplemented with blue, only radish developed a lower photosynthetic rate when grown under red LEDs (as we also found for cucumber; Figs 1, 4A). This suggests that vulnerability to decreases in photosynthetic rate associated with growth under red light alone may be subject to genetic variation.

The low Amax of the leaves that developed under 0B (Fig. 1) cannot be attributed to a low leaf N content, as the PNUE at Amax is lower for the 0B treatment than for the other treatments (Fig. 8B). Chl content and LMA can also be ruled out, as Amax expressed per unit leaf DW and per unit Chl is also lower for the 0B leaves (Fig. 8A). The nitrate fraction of the leaf N content has been reported to be relatively higher in leaves grown under low irradiance than those grown under a high irradiance (e.g. Felippe, et al., 1975). In the present study this nitrate effect on PNUE can be excluded as in both in the 0B and 30B leaves N in the form of nitrate was <10% of the total N content. The unresponsiveness of the stomata of 0B-grown leaves did limit Amax due to a more restricted CO2 diffusion into the leaf, as reflected by the lower Ci Ca−1 with increasing measuring irradiance in the 0B leaves compared with the other treatments (Fig. 4).

In contrast to Amax, the low α found for the 0B treatment (Table 1) is entirely related to a lower ΦPSII and not to a low Ci due to a low gsw (Fig. 4), as under both ambient O2 and non-photorespiratory conditions the relationship between Agross and an index of ETR (the product of ΦPSII and absorbed irradiance) did not differ significantly for the 0B and the 30B leaves (Fig. 2). If Ci was limiting assimilation of the 0B leaves at low irradiance, Agross per unit ETR would have been lower for 0B than for 30B at ambient O2 but not at low O2 (e.g. Harbinson et al., 1990). Therefore, the underlying cause of the relatively low photosynthetic rates at low irradiance of the 0B-grown leaves may be due to disorders in the development and functioning of the photosynthetic machinery itself. During the photosynthesis measurements the measuring-light spectrum was identical to the growth-light, so a higher α would be expected for the 0B treatment as the quantum yield for incident red light is known to be higher than that of blue light (McCree, 1972; Inada, 1976). Where the relatively low α measured for the treatments containing a high blue light percentage (50B, 100B) was to be expected based on the differences in quantum yields for the different wavelengths, the low α for the 0B treatment is unexpected and points to problems in the development and operation of photosynthesis. An Fv/Fm below 0.8, as measured for the 0B leaves, is normally associated with damage or long-term down-regulation of PSII in response to stress (e.g. Baker, 2008). Evidently red light alone, or the absence of blue light during growth, results in a dysfunction of the photosynthetic machinery with a particularly adverse effect on leaf tissue regions between the veins (Fig. 3). Matsuda et al. (2008) reported an Fv/Fm ≥0.8 for spinach leaves grown under white fluorescent light deficient in blue, so wavelengths beyond the blue region may also prevent a loss of Fv/Fm, as found for 100% red in this study.

Several diverse, spectrally related factors have been associated with inhibition of photosynthesis. Feedback down-regulation of photosynthesis is associated with carbohydrate accumulation in leaves (e.g. Stitt, 1991; Paul and Foyer, 2001). Britz and Sager (1990) found lower leaf photosynthesis associated with higher starch content at the end of the night period in soybean and sorghum leaves grown under low pressure sodium lamps emitting very little blue light and mainly amber/red light (∼595 nm), compared with leaves grown under daylight fluorescent tubes. In the case of the present experiments any such effects on carbohydrate transport and metabolism can be discounted as no differences in carbohydrate content at the end of the dark period were found between the treatments (Table 2). In wheat seedlings, inhibition of PSI and PSII development and Chl synthesis was reported upon exposing the root–shoot transition zone to 500 μmol m−2 s −1 pure red light (Sood et al., 2004), suggesting an unidentified problem related to transport of substances within the plant. In the present experiment, Chl content on a leaf DW basis was not impaired in the 0B treatment (Fig. 6); however, the higher Fv/Fm adjacent to the veins (Fig. 3) and the occasional chlorotic appearance between the veins also point to a potential transport problem. Schmid and co-workers related a depressed Fv/Fm and photosynthesis in chloroplasts of red light-grown green algae Acetabularia to uncoupling of antennae and PSII reaction centres due to reduced amounts of core antenna Chl–protein complexes (Wennicke and Schmid, 1987; Schmid et al. 1990a, b). The involvement of a blue light/UV-A photosensory pathway in the maintenance of PSII core protein synthesis has been postulated by Christopher and Mullet (1994), and Mochizuki et al. (2004) found a threshold intensity of 5 μmol m−2 s −1 blue light (470 nm) for activation of the PSII core protein D2-encoding gene psbD in Arabidopsis acting via cryptochromes, along with a non-blue-specific activation signal. An impaired ability to synthesize core proteins may be related to the low Fv/Fm and α that were found for the 0B-grown cucumber leaves; however, this theory cannot be directly linked to a problem with transport within the plant, as indicated by the heterogeneous Fv/Fm.

Blue light dose–responses

The physiological disorders associated with leaf development under red light alone were eliminated by adding only a small amount of blue light (7% or 7 μmol m−2 s −1; Fig. 1). Beside this response to blue, which may be characterized as a ‘qualitative’ or ‘threshold’ effect, the increase in Amax upon increasing the blue light percentage up to 50B clearly indicates that leaf photosynthesis also responds quantitatively to blue light.

The quantitative increase in Amax with an increasing proportion of blue light was associated with an increase in LMA (Fig. 7A), Chl content, and N per unit area (Table 1; Fig. 7B) and gsw at saturating irradiance (Fig. 4B). The larger gsw is due both to a larger number of adaxial stomata (Fig. 5) and a greater stomatal aperture. Blue light deficiency has been associated with a lower LMA in soybean (Britz and Sager, 1990), consistent with the lowest LMA that was found for the 0B-grown leaves here. A higher irradiance is usually found to lead to both a higher LMA and Amax (Poorter et al., 2009). The present results show that the quantitative relationship between LMA and Amax with increasing irradiance (Poorter et al., 2009, 2010) is also found for a varying blue percentage at a constant irradiance (Fig. 7A). In general, in parallel with leaf responses to irradiance, blue light is shown to stimulate ‘sun-type’ characteristics on the leaf level, even at the relatively low growth irradiance used in this study.

The question remains of which blue light-regulated response(s) can explain the differences in Amax of leaves grown under different blue light percentages? At a blue light percentage ≥22% Amax appears to change proportionally to changes in LMA, Chl, and PNUE (Fig. 8), although Chl per leaf DW (Fig. 6B) and Chl:N (Table 1) decrease slightly with an increasing percentage of blue light. Similar relationships between these leaf traits are usually observed with increasing irradiances, where Amax increases proportionally with LMA and N content per unit leaf area, and Chl:N decreases (e.g. Evans and Poorter, 2001). Leaf N content may therefore indeed be a limiting factor for Amax of leaves grown at an irradiance ≥22B. Regulation of potential Amax due to restrictions in cell size and the number of cell layers in a mature leaf as proposed by Oguchi et al. (2003) is also well in line with the correlation found between LMA and Amax in the present experiment. A restriction in intercellular space per unit leaf area may be expected to be associated with a limitation of N-requiring components of the photosynthetic machinery per unit leaf area. More unusual is the lower Amax per unit LMA, Chl, and N found for leaves grown under an irradiance containing ≤15B (Fig. 8). These results indicate that cell space within the leaf, N availability, and pigment content were sufficiently large to allow a higher Amax. Hogewoning et al. (2010) likewise found a lower Amax per unit LMA for cucumber leaves grown under high pressure sodium light (5% blue) compared with leaves grown under fluorescent tubes (23% blue) and an artificial solar spectrum (18% blue). Apparently leaves grown at an irradiance containing ≤15B are subject to limitations which may be related to the disorders associated with 0B leaves as discussed above, whereas at ≥22B the relationships between Amax and LMA, N, and Chl are very similar to usual leaf responses to irradiance.

The Chl a:b ratio was also conspicuously lower for 0B and 7B leaves, but remained stable at >15B (Table 1). This response is not in accordance with the usually measured increasing Chl a:b ratio with increasing irradiance during growth (Evans and Poorter, 2001), in contrast to the responses of the other leaf traits measured, which are in accordance with usual responses to irradiance.

Leaf responses to growth under blue light alone

Though the responses of Amax (Fig. 1), LMA, and Chl content (Fig. 6A) in the range 0B–50B display clear progressive trends, the results for the 100B treatment deviate from those trends. In contrast to 0B, 100B leaves did not show any signs of dysfunctional photosynthesis. One conspicuous contrast between red and blue light is the absence of cryptochrome and phototropin stimulation in pure red, whereas pure blue does stimulate cryptochromes, phototropins, and also phytochromes (Whitelam and Halliday, 2007). The 100B leaves invested relatively little in Chl considering their Amax (Fig. 7). The relative amount of active phytochrome expressed as the phytochrome photostationary state (PSS; calculated according to Sager et al., 1988) of the 100B leaves is also markedly lower than that of the other red/blue combinations (Table 1), which may indicate a role for phytochrome activity in the regulation of the Chl content–Amax relationship. As LMA has been shown to be much less affected than Amax at spectra containing relatively little blue (Fig. 8A; high pressure sodium light-grown leaves in Hogewoning et al., 2010), the lower Amax of 100B leaves compared with 50B leaves may be related to a limitation in LMA due to the absence of responses regulated by red light.

Conclusions

In this study, blue light has been shown to trigger both a qualitative signalling effect enabling normal photosynthetic functioning of cucumber leaves and a quantitative response stimulating leaf development normally associated with acclimation to irradiance intensity. Leaf acclimation to irradiance intensity may therefore be regulated by a limited range of wavelengths instead of the full PAR spectrum. Varying the blue light fraction offers the possibility to manipulate leaf properties under a low irradiance such that they would normally be associated with high irradiances. The possibility to grow plants under relatively low irradiance in a plant growth facility, with a relatively high photosynthetic capacity able to withstand irradiances under field conditions, is a useful practical consequence for research and agriculture.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the Dutch Technology Foundation STW, Applied Science Division of the NWO, and the Technology Program of the Ministry of Economic Affairs, Philips, and Plant Dynamics BV. We are grateful to Joost Ruijsch, Evert Janssen, and Gradus Leenders (equipment development), Annie van Gelder and Joke Oosterkamp (stomata analysis), Arjen van de Peppel (biochemical analysis), and Hennie Halm C/N measurements).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Amax

light-saturated assimilation

- Anet

net assimilation

- B

blue light percentage

- Chl

chlorophyll

- CiCa−1

CO2 concentration in leaf relative to CO2 concentration in leaf chamber air

- DW

dry weight

- ETR

electron transport rate

- Fv/Fm

ratio of variable to maximum fluorescence—the relative quantum efficiency for electron transport by PSII if all PSII reaction centres are open

- gsw

stomatal conductance

- gsw ratio

ratio of stomatal conductance on the adaxial and abaxial surface of the leaf

- LED

light-emitting diode

- LMA

leaf mass per unit leaf area

- PNUE

photosynthetic nitrogen use efficiency

- PSII

photosystem II

- PSS

phytochrome photostationary state

- Rdark

dark respiration

- α

light-limited quantum yield for CO2 fixation

- ΦPSII

relative quantum yield of PSII electron transport

References

- Baker NR. Chlorophyll fluorescence: a probe of photosynthesis in vivo. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2008;59:89–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker NR, Harbinson J, Kramer DM. Determining the limitations and regulation of photosynthetic energy transduction in leaves. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2007;30:1107–1125. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britz SJ, Sager JC. Photomorphogenesis and photoassimilation in soybean and sorghum grown under broad-spectrum or blue-deficient light-sources. Plant Physiology. 1990;94:448–454. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.2.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CS, Schuerger AC, Sager JC. Growth and photomorphogenesis of pepper plants under red light-emitting diodes with supplemental blue or far-red lighting. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science. 1995;120:808–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukhov NG, Drozdova IS, Bondar VV. Light response curves of photosynthesis in leaves of sun-type and shade-type plants grown in blue or red light. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology. 1995;30:39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Caird MA, Richards JH, Donovan LA. Nighttime stomatal conductance and transpiration in C3 and C4 plants. Plant Physiology. 2007;143:4–10. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.092940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher DA, Mullet JE. Separate photosensory pathways co-regulate blue-light/ultraviolet-A-activated psbD– psbC transcription and light-induced D2 and CP43 degradation in barley (Hordeum vulgare) chloroplasts. Plant Physiology. 1994;104:1119–1129. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.4.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, Poorter H. Photosynthetic acclimation of plants to growth irradiance: the relative importance of specific leaf area and nitrogen partitioning in maximizing carbon gain. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2001;24:755–767. [Google Scholar]

- Felippe GM, Dale JE, Marriott C. Effects of irradiance on uptake and assimilation of nitrate by young barley seedlings. Annals of Botany. 1975;39:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Folta KM, Maruhnich SA. Green light: a signal to slow down or stop. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2007;58:3099–3111. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genty B, Briantais JM, Baker NR. The relationship between the quantum yield of photosynthetic electron-transport and quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1989;990:87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Goins GD, Yorio NC, Sanwo MM, Brown CS. Photomorphogenesis, photosynthesis, and seed yield of wheat plants grown under red light-emitting diodes (LEDs) with and without supplemental blue lighting. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1997;48:1407–1413. doi: 10.1093/jxb/48.7.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbinson J, Genty B, Baker NR. The relationship between CO2 assimilation and electron-transport in leaves. Photosynthesis Research. 1990;25:213–224. doi: 10.1007/BF00033162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogewoning SW, Douwstra P, Trouwborst G, van Ieperen W, Harbinson J. An artificial solar spectrum substantially alters plant development compared with usual climate room irradiance spectra. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2010;61:1267–1276. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogewoning SW, Harbinson J. Insights on the development, kinetics, and variation of photoinhibition using chlorophyll fluorescence imaging of a chilled, variegated leaf. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2007;58:453–463. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inada K. Action spectra for photosynthesis in higher plants. Plant and Cell Physiology. 1976;17:355–365. [Google Scholar]

- Jarillo JA, Gabrys H, Capel J, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Cashmore AR. Phototropin-related NPL1 controls chloroplast relocation induced by blue light. Nature. 2001;410:952–954. doi: 10.1038/35073622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis PG. The estimation of resistance to carbon dioxide transfer. In: Sestak Z, Catsky J, Jarvis PG, editors. Plant photosynthetic production: manual of methods. The Hague: Junk; 1971. pp. 566–631. [Google Scholar]

- Kingston-Smith AH, Harbinson J, Williams J, Foyer CH. Effect of chilling on carbon assimilation, enzyme activation, and photosynthetic electron transport in the absence of photoinhibition in maize leaves. Plant Physiology. 1997;114:1039–1046. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.3.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler H, Buschmann C, Rahmsdorf U. The importance of blue light for the development of sun-type chloroplasts. In: Senger H, editor. The blue light syndrome. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1980. pp. 485–494. [Google Scholar]

- Massa GD, Kim HH, Wheeler RM, Mitchell CA. Plant productivity in response to LED lighting. Hortscience. 2008;43:1951–1956. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda R, Ohashi-Kaneko K, Fujiwara K, Goto E, Kurata K. Photosynthetic characteristics of rice leaves grown under red light with or without supplemental blue light. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2004;45:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda R, Ohashi-Kaneko K, Fujiwara K, Kurata K. Analysis of the relationship between blue-light photon flux density and the photosynthetic properties of spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) leaves with regard to the acclimation of photosynthesis to growth irradiance. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 2007;53:459–465. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda R, Ohashi-Kaneko K, Fujiwara K, Kurata K. Effects of blue light deficiency on acclimation of light energy partitioning in PSII and CO2 assimilation capacity to high irradiance in spinach leaves. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2008;49:664–670. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCree KJ. Action spectrum, absorptance and quantum yield of photosynthesis in crop plants. Agricultural Meteorology. 1972;9:191–216. [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki T, Onda Y, Fujiwara E, Wada M, Toyoshima Y. Two independent light signals cooperate in the activation of the plastid psbD blue light-responsive promoter in Arabidopsis. FEBS Letters. 2004;571:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nejad AR, van Meeteren U. Stomatal response characteristics of Tradescantia virginiana grown at high relative air humidity. Physiologia Plantarum. 2005;125:324–332. [Google Scholar]

- Oguchi R, Hikosaka K, Hirose T. Does the photosynthetic light-acclimation need change in leaf anatomy? Plant, Cell and Environment. 2003;26:505–512. [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi-Kaneko K, Matsuda R, Goto E, Fujiwara K, Kurata K. Growth of rice plants under red light with or without supplemental blue light. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 2006;52:444–452. [Google Scholar]

- Paul MJ, Foyer CH. Sink regulation of photosynthesis. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2001;52:1383–1400. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.360.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H, Niinemets U, Poorter L, Wright IJ, Villar R. Causes and consequences of variation in leaf mass per area (LMA): a meta-analysis. New Phytologist. 2009;182:565–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H, Niinemets U, Walter A, Fiorani F, Schurr U. A method to construct dose–response curves for a wide range of environmental factors and plant traits by means of a meta-analysis of phenotypic data. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2010;61:2043–2055. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sager JC, Smith WO, Edwards JL, Cyr KL. Photosynthetic efficiency and phytochrome photoequilibria determination using spectral data. Transactions of the ASAE. 1988;31:1882–1889. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid R, Fromme R, Renger G. The photosynthetic apparatus of Acetabularia mediterranea grown under red or blue light. Biophysical quantification and characterization of photosystem II and its core components. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 1990a;52:103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid R, Wennicke R, Fleischhauer S. Quantitative correlation of peripheral and intrinsic core polypeptides of photosystem II with photosynthetic electron-transport activity of Acetabularia mediterranea in red and blue light. Planta. 1990b;182:391–398. doi: 10.1007/BF02411390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD, Raschke K. Effect of light quality on stomatal opening in leaves of Xanthium strumarium L. Plant Physiology. 1981;68:1170–1174. doi: 10.1104/pp.68.5.1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Weyers JDB, Berry WG. Variation in stomatal characteristics over the lower surface of Commelina communis leaves. Plant, Cell and Environment. 1989;12:653–659. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder KA, Richards JH, Donovan LA. Night-time conductance in C3 and C4 species: do plants lose water at night? Journal of Experimental Botany. 2003;54:861–865. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sood S, Tyagi AK, Tripathy BC. Inhibition of photosystem I and photosystem II in wheat seedlings with their root–shoot transition zones exposed to red light. Photosynthesis Research. 2004;81:31–40. doi: 10.1023/B:PRES.0000028337.72340.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt M. Rising CO2 levels and their potential significance for carbon flow in photosynthetic cells. Plant, Cell and Environment. 1991;14:741–762. [Google Scholar]

- Tennessen DJ, Singsaas EL, Sharkey TD. Light-emitting diodes as a light-source for photosynthesis research. Photosynthesis Research. 1994;39:85–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00027146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornley JHM. Mathematical models in plant physiology: a quantitative approach to problems in plant and crop physiology. London: Academic Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Trouwborst G, Oosterkamp J, Hogewoning SW, Harbinson J, van Ieperen W. The responses of light interception, photosynthesis and fruit yield of cucumber to LED-lighting within the canopy. Physiologia Plantarum. 2010;138:289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD. Some relationships between the biochemistry of photosynthesis and the gas-exchange of leaves. Planta. 1981;153:376–387. doi: 10.1007/BF00384257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voskresenskaya NP, Drozdova IS, Krendeleva TE. Effect of light quality on organization of photosynthetic electron-transport chain of pea-seedlings. Plant Physiology. 1977;59:151–154. doi: 10.1104/pp.59.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellburn AR. The spectral determination of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. Journal of Plant Physiology. 1994;144:307–313. [Google Scholar]

- Wennicke H, Schmid R. Control of the photosynthetic apparatus of Acetabularia mediterranea by blue light. Analysis by light-saturation curves. Plant Physiology. 1987;84:1252–1256. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.4.1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitelam G, Halliday K. Light and plant development. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yorio NC, Goins GD, Kagie HR, Wheeler RM, Sager JC. Improving spinach, radish, and lettuce growth under red light-emitting diodes (LEDs) with blue light supplementation. Hortscience. 2001;36:380–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S-J, Snoeren TAL, Hogewoning SW, van Loon JJA, Dicke M. Disruption of plant carotenoid biosynthesis through virus-induced gene silencing affects oviposition behaviour of the butterfly. Pieris rapae. New Phytologist. 2010;186:733–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]