Abstract

Background

The prevalence and clinical course of pulmonary cryptococcosis in Sub-Saharan Africa are not well-described.

Methods

Consecutive HIV-infected adults hospitalized at Mulago Hospital (Kampala, Uganda) between September 2007 and July 2008 with cough ≥ 2 weeks were enrolled. Patients with negative sputum smears for acid-fast bacilli were referred for bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). BAL fluid was examined for mycobacteria, Pneumocystis jirovecii, and fungi. Patients were followed two and six months after hospital discharge.

Results

Of 407 patients enrolled, 132 (32%) underwent bronchoscopy. Of 132 BAL fungal cultures, 15 (11%) grew Cryptococcus neoformans. None of the patients were suspected to have pulmonary cryptococcosis on admission. The median CD4 count among those with pulmonary cryptococcosis was 23 cells/µL (IQR 7–51). Of 13 patients who completed six-month follow-up, four died and nine were improved, including five who had started antiretroviral therapy (ART) but had not received antifungal medication.

Conclusions

Pulmonary cryptococcosis is common in HIV-infected TB suspects in Uganda. Early initiation of ART in those with isolated pulmonary infection may improve outcomes, even without anti-fungal therapy. This finding suggests that some HIV-infected patients with C. neoformans isolated from respiratory samples may have colonization or localized infection.

Keywords: Pulmonary Cryptococcosis, HIV/AIDS, Bronchoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, a thin-walled non-mycelial budding yeast that is characterized by a thick polysaccharide capsule best seen on India ink stain.1 As one of the most common opportunistic infections, cryptococcal infection affects approximately one million HIV-infected patients worldwide each year, and is associated with high mortality.2, 3 In Sub-Saharan Africa, cryptococcal disease has been associated with 17% of all deaths among HIV-infected patients4 and 75% of deaths from opportunistic infections in men with pulmonary tuberculosis.5

Most HIV-infected individuals with cryptococcosis present with meningitis and, less commonly, with meningitis and pneumonia or isolated pneumonia. Although the lungs are the portal of infection, few studies have addressed the clinical significance of isolating C. neoformans from pulmonary specimens in persons with HIV infection. In particular, there have been no studies from Sub-Saharan Africa since the introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART). We describe the prevalence, clinical features and outcomes of HIV-infected Ugandans hospitalized with pneumonia who had C. neoformans isolated from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Consecutive HIV-infected adults admitted to Mulago Hospital in Kampala, Uganda between September 2007 and July 2008 were screened for study eligibility and enrolled after written informed consent. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had cough ≥ 2 weeks and a clinical diagnosis of pneumonia. Patients were ineligible if they had cough for > 6 months or were receiving anti-tuberculosis treatment.

Data Collection

Clinical and demographic information was collected using a standardized questionnaire. HIV infection was confirmed and CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts were measured. Standardized work-up for pneumonia included chest radiography and acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear examination of two sputum specimens. Two board-certified radiologists interpreted chest radiographs while blinded to clinical information and using a standardized data collection form. Laboratory technicians at the Uganda National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Programme (NTLP) Reference Laboratory examined sputum specimens for AFB by direct light microscopy and concentrated fluorescence microscopy according to standard protocols and as described previously.6 Processed sputum specimens were inoculated on two Lowenstein-Jensen slants. Cultures were read weekly and considered positive if any growth (≥ 1 colony forming unit) was identified within eight weeks. Patients were referred for bronchoscopy with BAL if both sputum examinations were negative for AFB.

Bronchoscopy

Two pulmonologists performed bronchoscopy according to standard protocol, which included monitoring with continuous pulse oximetry and provision of supplementary oxygen as needed. After administering nebulized and topical 1% lidocaine for airway anesthesia, and intramuscular midazolam for anxiolysis, the bronchoscopists conducted a thorough bronchoscopic inspection of all visible airways for lesions consistent with Kaposi’s sarcoma. Then, the bronchoscopists performed bronchoalveolar lavage in a subsegment of the lobe with the greatest infiltration on chest radiography or in a subsegment of the right middle lobe if the radiographic infiltrates were diffuse. Sterile, normal saline (0.9%) was instilled into an occluded subsegmental bronchus in serial 25 mL aliquots (up to a maximum of 125 mL) and then aspirated until at least 50 mL of BAL fluid were returned. BAL fluid was sent for microbiologic tests, three mL of which were sent for fungal studies.

BAL Specimen Analysis

Trained laboratory technicians analyzed BAL fluid for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (AFB smear and Lowenstein-Jensen culture), Pneumocystis jirovecii (modified Giemsa stain), and other fungi (potassium hydroxide (KOH) stain, India ink stain, and culture on Sabouraud’s agar). Fungal stains and culture were performed in the Microbiology Department of Mulago Hospital using a standardized method. In brief, BAL fluid was concentrated at 450 relative centrifugal force (RCF) for five minutes, and the supernatant then poured out. A loopful of the sediment was inoculated onto Sabouraud’s media for up to 30 days, and the remainder was smeared on two slides for India ink and KOH.7 Growth of C. neoformans was identified by presence of mucoid, cream-colored colonies and confirmed using the urease test and India ink stain.

Patient Follow-up

Vital status was assessed in all patients either by telephone or in-person two months after hospital discharge. Patients who returned in-person were administered a standardized clinical questionnaire and underwent physical examination. In addition, patients who had C. neoformans isolated from BAL fluid were interviewed by telephone at four and six months after hospital discharge to determine vital status.

Statistical Analysis

We first performed bi-variate analyses comparing patients who had pulmonary cryptococcosis with those who did not, using the chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for dichotomous variables, and the Mann-Whitney rank-sum test for non-normally distributed continuous variables. We calculated the diagnostic accuracy of fungal stain for pulmonary cryptococcosis with exact binomial confidence intervals. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 10.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA), with the level of significance specified in reference to a two-tailed, type-I error (p-value) < 0.05.

Ethical Issues

The Makerere University Faculty of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee, the Mulago Hospital Institutional Review Board, the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research, and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology approved the protocol. Some of these patients have been previously included in a published study focused on diagnosis of tuberculosis.8

RESULTS

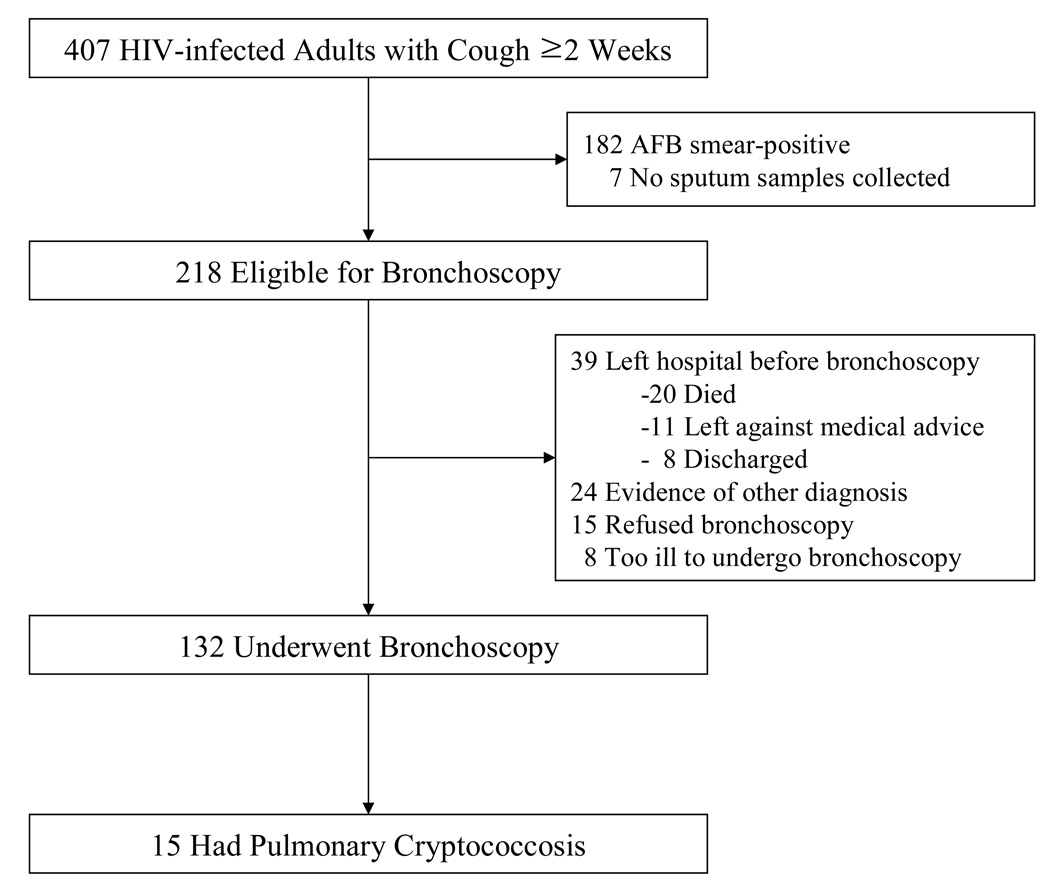

Of 407 HIV-infected adult patients enrolled, 218 (54%) were eligible for bronchoscopy and the 132 (32%) patients who underwent the procedure were included in the analysis (Figure 1). Demographic and clinical characteristics were similar between those who did and did not undergo bronchoscopy (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Numbers of patients screened, eligible, and enrolled

BAL fluid fungal cultures from 15 (11%) patients who underwent bronchoscopy grew C. neoformans. Pulmonary tuberculosis (39%), bacterial pneumonia (23%), pulmonary Kaposi sarcoma (5%), and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (3%) were the principal final diagnoses among the remaining patients. Demographic characteristics, presenting clinical symptoms, and physical findings were not significantly different between patients who did and did not have C. neoformans isolated from BAL fluid, except that those with C. neoformans were less often short of breath (p=0.01) (Table 1). In addition, those with C. neoformans isolated had lower median CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts (23 vs. 93 cells/µL, p=0.007) and tended to be less likely to be taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) (0% vs. 19%, p=0.06).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristics | Overall (N=132) |

Pulmonary Cryptococcosis (N=15) |

Other Diagnosis (N=117) |

p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (IQR) | 32 (28–38) | 33 (28–40) | 32 (27–38) | 0.60 |

| Female, (%) | 76 (58) | 9 (60) | 67 (57) | 0.53 |

| HIV status known (%) | 96 (73) | 11 (73) | 85 (73) | 0.61 |

| ART on admission (%) | 22 (17) | 0 (0) | 22 (19) | 0.06 |

| Median CD4, cells/µL (IQR) | 67 (17–191)* | 23 (7–51) | 93 (23–206)† | 0.007 |

| Fever (%) | 129 (98) | 14 (93) | 115 (98) | 0.23 |

| Median duration of fever, weeks (IQR) |

4 (2–8) | 6 (4–8) | 4 (2–8) | 0.16 |

| Weight loss (%) | 124 (94) | 14 (93) | 110 (94) | 0.92 |

| Median duration of cough, weeks (IQR) |

4 (3–8) | 4 (3–8) | 4 (3–8) | 0.98 |

| Shortness of breath (%) | 83 (63) | 5 (33) | 78 (67) | 0.01 |

| Median duration of shortness of breath, weeks (IQR) |

2 (1–4) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–4) | 0.06 |

| Chest pain (%) | 88 (67) | 12 (80) | 76 (65) | 0.25 |

| Hemoptysis (%) | 41 (36)‡ | 7 (50)§ | 34 (34)¶ | 0.20 |

| Median respirations/minute (IQR) | 25 (20–32) | 26 (18–32) | 24 (20–30) | 0.64 |

| Median % SpO2 (IQR) | 97 (93–98) | 97 (94–98) | 97 (92–98) | 0.48 |

| Lung examination | 0.81 | |||

| Normal (%) | 38 (29) | 3 (20) | 35 (30) | |

| Rhonchi (%) | 5 (4) | 0 | 5 (4) | |

| Crepitations (%) | 87 (66) | 12 (80) | 75 (64) | |

| Bronchial breath sounds (%) | 2 (2) | 0 | 2 (2) |

n=130,

n=115,

n=113,

n=14,

n=99

IQR=interquartile range

SpO2 = oxygen saturation

Clinical Presentation

The most frequent presenting symptoms among the 15 patients who had C. neoformans were fever (93%) and weight loss (93%) (Table 1). The median duration of cough was four weeks (IQR 3–8 weeks). Most patients had tachypnea (median respiratory rate, 26 breaths/minute), but only three of them had room air oxygen saturations below 93%. The majority of patients (80%) had crepitations on auscultation of the chest.

Chest Radiographic Findings

Chest radiographs were available in 14 of 15 patients who had C. neoformans isolated from BAL fluid. The most common radiographic patterns were interstitial infiltrates (N=4, 29%), lobar consolidation (N=3, 21%), or a mixed pattern (N=3, 21%) (Table 2). The distribution of parenchymal infiltrates was diffuse in 55% of patients.

Table 2.

Chest Radiographic findings of 14 patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis

| Radiographic pattern | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Interstitial infiltrates | 4 (29) |

| Lobar consolidation | 3 (21) |

| Hilar /Mediastinal lymphadenopathy | 3 (21) |

| Cavitary infiltrates | 2 (14) |

| Pleural effusion | 2 (14) |

| Normal (no abnormality) | 2 (14) |

| Mixed * | 3 (21) |

| Distribution of parenchymal infiltrates † | |

| Diffuse | 6 (55) |

| Focal | 5 (45) |

combination of : consolidation/linear opacity, consolidation/pleural effusion, or cavity/consolidation

3 cases excluded because of a lack of parenchymal infiltrates

Diagnostic Accuracy of Fungal Staining

India ink staining of BAL fluid was positive in seven of 15 patients with positive C. neoformans cultures (sensitivity 47%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 21–73%) and negative in 116 of 117 patients with negative cultures (specificity 99%, 95% CI 95–100%). The positive predictive value of India ink staining was 88% (95% CI 47–100%) and the negative predictive value of staining was 94% (95% CI 88–97%).

Clinical Course

Pulmonary cryptococcosis was not suspected by ward physicians in any of the 15 patients in whom C. neoformans was isolated from BAL. At the time of admission, pulmonary tuberculosis was suspected in six of those patients, bacterial pneumonia in six, pulmonary Kaposi’s sarcoma in one, cryptococcal meningitis in one, and tuberculous meningitis in one. During their hospital admission, eight (53%) patients had a second pulmonary process identified: six had pulmonary tuberculosis, one pulmonary Kaposi’s sarcoma, and one Pneumocystis pneumonia (Table 3). Six (40%) patients were diagnosed with accompanying cryptococcal meningitis. Meanwhile, of 117 patients who did not grow C. neoformans from BAL fluid, two patients had cryptococcal meningitis without pulmonary cryptococcosis.

Table 3.

Summary of 15 patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis

| No | Sex | Age | CD4 | Co-morbid illness | Meningitis | Antifungal therapy | ART | 2-month status | 6-month status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 36 | 9 | - | + | Fluconazole | U | Died | - |

| 2 | F | 29 | 37 | PKS | − | Fluconazole for oral candidiasis | − | Died | - |

| 3 | M | 48 | 165 | - | − | - | − | Improved* | Died |

| 4 | M | 33 | 4 | - | + | Fluconazole | − | Improved | Died† |

| 5 | F | 29 | 29 | Culture-positive PTB | + | Fluconazole | + | Improved | Improved |

| 6 | F | 54 | 7 | Culture-negative PTB‡ | + | Amphotericin B + Fluconazole | + | Improved | Improved |

| 7 | F | 33 | 23 | Culture-negative PTB‡ | + | Amphotericin B + Fluconazole | + | Improved | Improved |

| 8 | F | 28 | 7 | - | + | Amphotericin B + Fluconazole | + | Improved | Improved |

| 9 | M | 38 | 51 | - | − | - | + | Improved | Improved |

| 10 | F | 18 | 54 | - | − | - | + | Improved | Improved |

| 11 | M | 52 | 10 | PCP | − | - | + | Improved | Improved |

| 12 | M | 33 | 41 | Culture-negative PTB‡ | − | - | + | Improved | Improved |

| 13 | F | 18 | 11 | - | − | - | + | Improved | Suspected PCP |

| 14 | M | 33 | 4 | Culture-positive PTB | − | Fluconazole for oral candidiasis | + | Improved | Lost to follow-up |

| 15 | F | 41 | 226 | Culture-positive PTB | − | - | U | Lost to follow-up | Lost to follow-up |

Respiratory symptoms improved, but gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea and vomiting) developed.

Died during readmission due to gastrointestinal symptoms.

All of them were AFB smear-negative, but improved with anti-TB medication.

B/P=Bacterial pneumonia; PKS=pulmonary Kaposi’s sarcoma; PTB=pulmonary tuberculosis; CM=cryptococcal meningitis; TBM=Tuberculous meningitis; ART=antiretroviral therapy after discharge; U = unknown

All 15 patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis were initially treated with antibiotics for presumed bacterial pneumonia. Of the six patients with both pulmonary cryptococcosis and cryptococcal meningitis, three were treated with amphotericin B (50 mg/day for two weeks) and then fluconazole (400 mg daily for eight weeks). Three were treated with fluconazole (400 mg daily for 10 weeks) alone. Of the nine patients with isolated pulmonary cryptococcosis without meningitis, two received fluconazole (200 mg daily for two weeks) for oral candidiasis and seven were not prescribed any anti-fungal medications. All 15 patients improved clinically and were discharged from the hospital (median hospitalization 8 days, IQR 5–16 days).

Of 15 patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis, nine (60%) survived six months, four died, and two were lost to follow up. Of four patients who died, two were known to have died within two months after discharge; one who had cryptococcal meningitis diagnosis during hospital admission and was treated with fluconazole (Patient 1) and one who had pulmonary Kaposi’s sarcoma and was treated with two weeks of fluconazole (200 mg) (Patient 2). Two additional patients who were alive at two-month follow up died before six-month follow up, both after developing severe gastroenteritis. Of the two lost to follow up, one person was known to have survived at least two months after discharge.

Of the seven patients who were not prescribed antifungal medicine at hospital discharge, five survived, one was lost to follow up, and one died at six-month follow-up. All five survivors who remained asymptomatic at six-months had started ART after discharge, but the one patient who died had not started ART (Patient 3).

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we present the first detailed review of HIV-infected patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis reported since the widespread introduction of ART in Sub-Saharan Africa. We found that the prevalence of pulmonary cryptococcosis among all HIV-infected patients hospitalized with pneumonia who underwent bronchoscopy was 11%. The diagnosis of pulmonary cryptococcosis was not suspected in any of these 15 patients prior to diagnostic testing, and known survival of the patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis was low (9/15, 60% at six months). However, 33% of the patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis improved without anti-fungal therapy up to six-month follow-up. This finding was unexpected and suggests that some HIV-infected patients with Cryptococcus isolated from respiratory samples may have localized infection or colonization.

In previous clinical studies from Sub-Saharan Africa prior to ART introduction, the prevalence of pulmonary cryptococcosis ranged from 0 to 13% in HIV-infected patients with respiratory symptoms.9–11 While the number of cryptococcosis cases has declined significantly in the United States following the introduction of ART, cases continue to be diagnosed in individuals with limited access to health care.12 In our study, only 22 (17%) patients overall and none of the 15 patients who had C. neoformans isolated from BAL fluid were receiving ART at the time of hospital admission. Moreover, the median CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of our study sample indicates an advanced level of immunosuppression. Since access to ART remains limited in Uganda despite the initiatives to scale up distribution, it is not surprising that the prevalence of pulmonary cryptococcosis among HIV-infected patients with pneumonia remains high.

In spite of its high prevalence in this population sample, the diagnosis of pulmonary cryptococcosis was not suspected in any patient at the time of hospital admission. Many clinicians in Sub-Saharan Africa may be unaware of the epidemiology of pulmonary cryptococcosis. In South Africa, clinicians suspected the diagnosis of pulmonary cryptococcosis prior to death in only one percent of patients who had pulmonary cryptococcosis confirmed by autopsy.13 We found, as have others, that the clinical symptoms, physical exam findings, and radiographic manifestations of pulmonary cryptococcosis are non-specific and similar to those of other opportunistic pulmonary diseases, reinforcing the importance of establishing a confirmed microbiologic diagnosis whenever possible.14–18 Therefore, clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for pulmonary cryptococcosis, particularly among patients with very advanced immunosuppression (CD4+ T-lymphocyte count < 50 cells/µL).

In our study, five of 13 patients had improved at six-months without anti-fungal treatment, and all five had initiated ART. One potential explanation for this unexpected finding is that ART-associated immune reconstitution enabled clearance of C. neoformans from the lungs. ART and the resulting immune reconstitution has been shown to be successful and is recommended as first-line therapy for several opportunistic infections such as cryptosporidiosis, microsporidiosis, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) for which effective antimicrobial therapies are lacking. Zolopa et al reported that early ART was associated with fewer deaths or progressions to AIDS at 48 weeks compared to deferred ART in HIV-infected patients presenting with an acute opportunistic infection.19 However, three mortality studies done in Uganda on cryptococcosis after initiation of ART have shown disappointing results. One study found that the mortality of cryptococcal meningitis remained high despite the availability of ART.20 Another study found that asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia was an independent risk factor associated with an increased mortality during the first 12 weeks of ART.21 A third study reported that five out of five HIV infected patients with CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts ≤ 100cells/µL and asymptomatic cryptococcal antigenemia died within two months after starting ART without fluconazole treatment.22 Taken together, these data suggest that ART alone is insufficient to eradicate disseminated C. neoformans infection from patients with advanced immunosuppression but that it may be sufficient for C. neoformans infection limited to the lungs.

We assume that the five patients who improved without antifungal medicine in spite of their low CD4+ T lymphocyte counts in our study did not have disseminated disease, but instead had localized infection or colonization of the airway by Cryptococcus. Another possibility is that the fungal cultures were false positive and represent laboratory contamination. We cannot rule out the possibility of precipitation of Cryptococcus from the environment on to the plates during the procedure of inoculation because C. neoformans has been isolated from house dust in Central Africa.23, 24 However this possibility is unlikely because dust collection for Cryptococcus culture needs large amounts (200–283 liters) of air exchange25 and the inoculation time was short.

While isolating C. neoformans from cerebrospinal fluid has been shown to be highly specific for cryptococcal meningitis1, the significance of isolating C. neoformans from respiratory specimens has not been well established. Because the lungs are the portal of entry, C. neoformans organisms may be found in the airways in the absence of disease. A definitive diagnosis of cryptococcal pneumonia may require identification of the organism in tissue obtained from a biopsy or a surgical specimen.26, 27 In practice, experts advocate treatment whenever respiratory specimens grow C. neoformans in the setting of a compatible clinical syndrome in HIV-infected patients.28, 29 However, the potential presence of co-infections in HIV-infected patients makes it difficult to define a “compatible clinical syndrome.” Of 15 pulmonary cryptococcosis patients in our study, eight (53%) had two pulmonary processes. In these patients, it is unclear whether the clinical and radiographic findings were due to cryptococcosis, the other pulmonary process, or both. No study has proved the presence of colonization of C. neoformans in the airways of HIV-infected patients, though colonization of the nasopharynx has been documented.30 Further studies and expert consensus are needed to define the significance of isolating C. neoformans from respiratory specimens.

The possibility of localized infection or colonization of C. neoformans in the airway of HIV-infected patients calls into question the principle that all HIV-infected patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis need antifungal treatment. Whether to “treat or observe” is a difficult decision in HIV-negative patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis because of the difficulty in distinguishing infection from colonization.31, 32 This decision is more difficult in HIV-infected patients, given the high mortality associated with cryptococcosis in this population. CD4+ T lymphocyte counts and serum cryptococcal antigen test may be of help in making a right decision.

There are some limitations to our study. First, we did not perform serum cryptococcal antigen testing, which might have helped us differentiate between isolated pulmonary disease and disseminated disease. Second, we did not determine the serotype of C. neoformans isolates obtained during our study. A previous study from Uganda showed that all 36 cryptococcal isolates causing disease were confirmed C. neoformans var grubii, serotype A.4 Last, the small number of patients in this series limited our statistical power to identify clinical and radiographic characteristics that might differentiate those with pulmonary cryptococcosis from those with other respiratory infections.

In summary, pulmonary cryptococcosis is common in HIV-infected TB suspects in Uganda and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of HIV-infected individuals with pneumonia. Additional studies should determine whether initiation of ART without antifungal therapy is sufficient treatment for patients with pulmonary cryptococcosis without evidence of disseminated disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the patients who participated in this study, and the staff and administration of Mulago Hospital for facilitating this research, especially Chaplain Duku who performed fungal stains and culture.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

# This study was presented as a poster at the American Thoracic Society International Conference 2009, San Diego, California on May 17 2009

Disclosure of Financial support

This study was supported by grants K23AI080147, K24HL087713, and R01HL090335 from the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Samuel D Yoo, Email: yoouga@yahoo.com.

William Worodria, Email: worodria@yahoo.com.

JL Davis, Email: lucian.davis@ucsf.edu.

Adithya Cattamanchi, Email: acattamanchi@medsfgh.ucsf.edu.

Saskia den Boon, Email: sdenboon@muucsf.org.

Rachel Kyeyune, Email: smilin.rasasa@gmail.com.

Harriet Kisembo, Email: harkisembo@yahoo.co.uk.

Laurence Huang, Email: lhuang@php.ucsf.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kobayashi G. Fungi. In: Davis BD, editor. Microbiology. Philadelphia: J.B: Lippincott Company; 1980. p. 751. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park BJ, Wannemuehler KA, Marston BJ, et al. Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2009;23(4):525–530. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328322ffac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powderly WG, Finkelstein D, Feinberg J, et al. NIAID AIDS Clinical Trials Group. A randomized trial comparing fluconazole with clotrimazole troches for the prevention of fungal infections in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(11):700–705. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503163321102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.French N, Gray K, Watera C, et al. Cryptococcal infection in a cohort of HIV-1-infected Ugandan adults. AIDS. 2002;16:1031–1038. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200205030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Churchyard GJ, Kleinschmidt I, Corbett EL, et al. Factors associated with an increased case-fatality rate in HIV-infected and non-infected South African gold miners with pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4(8):705–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kent PT, Kubica G. Public Health Mycobacteriology. A Guide for the Level III Laboratory. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koneman EW, Robert G. Mycotic disease. In: Henry JB, editor. Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1984. p. 1186. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cattamanchi A, Davis JL, Worodria W, et al. Poor Performance of Universal Sample Processing Method for Diagnosis of Pulmonary Tuberculosis by Smear Microscopy and Culture in Uganda. J Clin Microbiol. 2008 Oct;:3325–3329. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01175-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daley CL, Mugusi F, Chen LL, et al. Pulmonary complications of HIV infection in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. Role of bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:105–110. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.1.8680664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant AD, Djomand G, Smets P, et al. Profound immunosuppression across the spectrum of opportunistic disease among hospitalised HIV-infected adults in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. AIDS. 1997;11:1357–1364. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199711000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batungwanayo J, Taelman H, Lucas S, et al. Pulmonary diseases associated with the human immunodeficiency virus in Kigali, Rwanda. A fiberoptic bronchoscopic study of 111 cases of undetermined etiology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:1591–1596. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.6.8004318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mirza SA, Phelan M, Rimland D, et al. The changing epidemiology of cryptococcosis: an update from population-based active surveillance in 2 large metropolitan areas, 1992–2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2003 Mar 15;36(6):789–794. doi: 10.1086/368091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong ML, Back P, Candy G, et al. Cryptococcal pneumonia in African miners at autopsy. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007;11(5):528–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wasser L, Talavera W. Pulmonary cryptococcosis in AIDS. Chest. 1987 Oct;92(4):692–695. doi: 10.1378/chest.92.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark RA, Greer DL, Valanis GT, et al. Cryptococcus neoformans pulmonary infection in HIV-1-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1990;3(5):480–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyohas MC, Roux P, Bollens D, et al. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: localized and disseminated infections in 27 patients with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1995 Sep;21(3):628–633. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.3.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeLorenzo LJ, Huang C, Maguire GP, et al. Roentgenographic patterns of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in 104 patients with AIDS. Chest. 1987 Mar;91(3):323–327. doi: 10.1378/chest.91.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoo DJ, Lee K, Munderi P, et al. Clinical and Bronchoscopic Findings in Ugandans with Pulmonary Kaposi's Sarcoma. Kor J Intern Med. 2005;20:290–294. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2005.20.4.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zolopa A, Anderson J, Komarow L, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy reduces AIDS progression/death in individuals with acute opportunistic infections: a multicenter randomized strategy trial. PLoS. One. 2009;4(5):e5575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kambugu A, Meya DB, Rhein J, et al. Outcomes of Cryptococcal meningitis in Uganda before and after the availability of HAART. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 June 1;46(11):1694–1701. doi: 10.1086/587667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liechty C, Solberg P, Were W, et al. Asymptomatic serum cryptococcal antigenemia and early mortality during antiretroviral therapy in rural Uganda. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12(8):929–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meya D, Castelnuovo B, Kambugu A, et al. Cost effectiveness of serum cryptococcal antigen (CRAG) screening to prevent death in HIV- infected persons with CD4 < 100/µL in sub-Saharan Africa. TUAD104 [abstract]. Presented at: 5th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevent; Cape town, South Africa. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swinne D, Deppner M, Maniratunga S, et al. AIDS-associated cryptococcosis in Bujumbura, Burundi: an epidemiological study. Med Mycol. 1991;29:25–30. doi: 10.1080/02681219180000051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swinne D, Taelman H, Batungwanayo J, et al. Ecology of Cryptococcus neoformans in central Africa. Med Trop (Mars) 1994;54:53–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kidd SE, Chow Y, Mak S, et al. Characterization of Environmental Sources of the Human and Animal Pathogen Cryptococcus gattii in British Columbia, Canada, and the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1433–1443. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01330-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diamond RD. Cryptococcus neoformans. In: Mandell GL, editor. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. pp. 2707–2718. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldman C. Cryptococcal pneumonia. Clin Pulm Med. 2003;10(2):67–71. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox GM, Perfect J. Cryptococcal pneumonia. Uptodate. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saag MS, Graybill R, Larsen RA, et al. Practice Guideline for the Management of Cryptococcal Disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000 Apr;30(4):710–718. doi: 10.1086/313757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sukroongreung S, Eampokalap B, Tansuphaswadiku S, et al. Recovery of Cryptococcus neoformans from the nasopharynx of AIDS patients. Mycopathologia. 1999;143:131–134. doi: 10.1023/a:1006909532185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aberg JA, Mundy LM, Powderly WG. Pulmonary Cryptococcosis in Patients Without HIV infection. Chest. 1999;115:734–740. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.3.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aberg JA. Pulmonary Cryptococcosis in Normal Hosts. Chest. 2003;124:2049–2051. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.6.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]