Abstract

Objective

We sought to examine rates of eating disorder symptoms among seriously overweight children seeking treatment using the Eating Disorder Examination for Children (ChEDE) and to provide initial data about their association with treatment outcome.

Method

Overweight children (N = 27) 8–13 years old were interviewed using the ChEDE before participating in a family-based behavioral treatment program. Height and weight were measured pretreatment, posttreatment, and approximately 8 months posttreatment.

Results

Fifteen percent of children reported subjective bulimic episodes (SBE). Weight loss did not differ for children with and without SBEs, but concerns about body shape were related to larger weight losses during treatment.

Conclusion

A considerable minority of treatment-seeking overweight children report an episodic sense of loss of control over eating. Loss of control is related to other disordered eating attitudes and behaviors, but does not appear to affect treatment outcome. Future studies are needed to replicate these initial findings.

Keywords: overweight, children, Eating Disorder Examination for Children, loss of control, binge eating

Introduction

Binge eating, or the consumption of a large amount of food with an accompanying sense of loss of control over one’s eating, has been associated with the severity of overweight and psychosocial morbidity in adults.1–3 Recent reports also have described the occurrence of binge eating in children,4 and evidence suggests that binge eating and its correlates, concerns about eating, body shape, and weight, are more prevalent among overweight children than among normal weight children.5–8

The Eating Disorder Examination (EDE), a widely used semistructured interview to assess eating disorder behaviors and attitudes among adults,9 has been modified for children.10 To date, two studies have used the Eating Disorder Examination-Children’s version (ChEDE) to assess binge eating and related behaviors in children. Decaluwe and Braet11 conducted ChEDE interviews with 196 overweight children and adolescents seeking weight loss treatment. Nine percent reported objective bulimic episodes (OBE; i.e., eating an objectively large amount of food with an accompanying sense of loss of control over eating). OBEs were more common among girls than boys, and compared with children without these episodes, those who reported OBEs were more overweight and endorsed greater concerns about eating and shape.

Similarly, Tanofsky-Kraff et al.8 used the ChEDE to examine eating disorder symptoms in 82 overweight and 80 normal weight children ages 6–13 years. Loss of control over eating was more prevalent among overweight children (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 85th percentile for age and gender) than among normal weight children. Overweight children also reported significantly more dietary restraint, concerns about eating, body shape, and weight, and were more likely to report a loss of control over eating than were normal weight children. Moreover, children who were more overweight (i.e., BMI ≥ 95th percentile) had the greatest level of concern about weight and shape. Finally, children who experienced a loss of control over eating reported significantly more eating-disordered cognitions compared with those who did not, irrespective of BMI. Thus, a loss of control over eating appears to be common among overweight children and may be related to other eating-disordered attitudes and behaviors.

Despite the evidence that binge eating may affect overweight children, little is known about binge eating and related attitudes among overweight children seeking weight loss treatment, or about the association between eating disorder symptoms and treatment outcome. For example, although there has been controversy about the effect of behavioral weight management programs12 on binge eating among adults, evidence from the study of overweight binge eaters has suggested that weight control programs may help ameliorate binge eating and weight losses after participation in weight management programs and do not appear to differ between overweight adults with and without binge eating disorder (BED).13–16 However, the effect of binge eating on the outcome of a behavioral weight management program for overweight children is unknown. Thus, the current study was designed to provide preliminary information on binge eating among a group of severely overweight children seeking treatment and the relation between children’s eating behaviors and the outcome of a family-based behavioral weight management program.

Methods

Participants

Participants (N = 27) were recruited to participate in a family-based treatment for seriously overweight children through advertisements in local newspapers and letters distributed to pediatricians and family physicians. Parents who responded to advertisements or letters were asked a series of screening questions. To be eligible for the study, children had to be between the ages of 8 and 13 years and to be greater than 160% of the ideal body weight (IBW) for their age, height, and gender according to World Health Organization (WHO) charts.17 Children who endorsed current psychiatric symptomatology that was serious enough to warrant immediate treatment and those who were currently enrolled in a weight control program were excluded.

Children were weighed in street clothing without shoes using a balance beam scale and height was measured using a stationary stadiometer. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters, and percentage of IBW was determined using the WHO charts.17 Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Before treatment, all children were interviewed about their eating behaviors.

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics (N = 27)

| M | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 10.07 | 1.60 | 6.5–13.0 |

| Weight (lbs) | 77.9 | 17.5 | 51.6–123.2 |

| BMI | 33.5 | 4.5 | 27.4–45.5 |

| % of Ideal Body Weight | 187 | 21 | 160–243 |

| Race | |||

| % African American | 22% | ||

| % Caucasian | 78% | ||

| Gender | |||

| % Female | 44% | ||

| % Male | 66% | ||

Note: BMI = body mass index.

Assessments

ChEDE

The ChEDE is a semistructured clinical interview designed to assess the full range of eating disorder behaviors. It was adapted from the adult EDE9 with modifications made to assess intent rather than actual behaviors.10 In addition, the language of the ChEDE interview was simplified for 8–14-year-old children, and the assessment of two items measuring overvaluation of shape and weight is done with the help of a sorting task. Several studies using the adult EDE support its discriminant validity, internal consistency, concurrent validity, and test-retest reliability.9,18 The ChEDE appears to have adequate interrater reliability, internal consistency, and discriminant validity.19,20

Most of the items on the ChEDE interview are rated on a 7-point, forced-choice scale ranging from 0 to 6, with higher numbers indicating greater severity or frequency. Items with diagnostic relevance are coded as present or absent, and the frequency of these symptoms is also rated. Individual items are averaged to generate four subscales: (a) Restraint, a measure of an individual’s conscious efforts to limit food intake; (b) Eating Concern, a measure of preoccupation with food and eating; (c) Shape Concern, a measure of dissatisfaction or preoccupation with body shape; and (d) Weight Concern, a measure of dissatisfaction or preoccupation with weight.

The ChEDE also provides a detailed classification of overeating. In this part of the interview, the child is asked to talk about any instances when she or he has “really eaten too much” at one time. The episodes are then classified into four different forms of overeating following the guidelines developed by Fairburn and Cooper9 for the adult version of the EDE. Specifically, distinctions are made between episodes in which a child endorses a loss of control over eating, and those in which there is no loss of control. In addition, overeating is differentiated according to the amount of food consumed in an episode. An episode of overeating is rated as large by the interviewer when the amount of food consumed is objectively more than that typically eaten given the circumstances and the age of the child. Thus, episodes in which the amount of food is determined to be objectively large and in which there is a loss of control over eating (OBE) are distinguished from those in which there is loss of control but subjectively large amounts are consumed (subjective bulimic episodes [SBE]). Similarly, episodes in which there is not a loss of control over eating but a large amount is consumed (objective overeating [OO]) are distinguished from those in which the amount of food is not rated as large by the interviewer (subjective overeating [SO]).

For the current study, doctoral-level clinicians trained on the adult and children’s version of the EDE administered the ChEDEs. In addition, three items that are difficult to interpret among severely overweight children were omitted. Specifically, questions about feelings of fatness, sensations of a flat stomach, and maintenance of a low weight were excluded.

Treatment and Follow-Up

Families participated in a 10–12-session family-based behavioral intervention designed to increase healthy eating behaviors and physical activity and decrease unhealthy eating habits and sedentary behaviors. The intervention was adapted from the family-based weight management program developed by Epstein and Squires.21 In addition, families were seen for a follow-up session that occurred approximately 8 months (range, 4–13 months) after the final treatment session. During this follow-up visit, children again had their heights and weights measured. Three of the 27 children for whom ChEDE data are available did not complete treatment. Thus, data related to treatment outcome are based on the sample of the 24 children who completed both the ChEDE and started the treatment program. Additional details on the treatment program and results of treatment have been reported elsewhere.22

Analytic Plan

Means of continuous and frequency counts of categorical variables were computed to describe the sample. Because no children reported OBEs, remaining analyses compared children reporting SBEs with those reporting none. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare children with and without SBEs on EDE subscales. To evaluate the relation between eating behavior and treatment outcome, we compared children with SBEs with those without on percent over IBW at pretreatment and posttreatment using a repeated-measures ANOVA and controlling for baseline percent over IBW. Similarly, after controlling for pretreatment body weight, we predicted change in percent over ideal weight from pretreatment to posttreatment from ChEDE subscale scores using a hierarchical linear regression equation.

Results

Eating Behavior

On the ChEDE, 18 (66.7%) children answered yes to the initial probe about having eaten too much during the past month, and overeating episodes were further classified among these children. Rates of overeating on the ChEDE are shown in Table 2. Fifty-nine percent (n = 16) of the total sample reported an episode of either SO or OO in the past month. Of the 16 children who indicated that they had overeaten within the past month, 2 reported an episode in which the amount of food consumed was deemed objectively large, and the remainder reported overeating an amount that the interviewer did not consider to be objectively large.

TABLE 2.

Percent of children reporting overeating episodes on the ChEDE

| Large Amount |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Loss of Control | Yes | Objective bulimic episode (OBE) | Subjective bulimic episode (SBE) |

| 0.0% | 14.8% (n = 4) | ||

| No | Objective overeating (OO) | Subjective overeating (SO) | |

| 7.4% (n = 2) | 51.8% (n = 14) | ||

Note: Two children endorsed multiple types of eating episodes. One reported OO and SBE, and one reported SO and SBE. ChEDE = Eating Disorder Examination children’s version.

Fifteen percent (n = 4) of children endorsed an episode in which they experienced a loss of control over eating during the past month. However, none reported consuming a large amount of food in conjunction with this loss of control. Consequently, all episodes of loss of control were rated as SBE. Of the 4 children who reported a loss of control, 2 reported one episode in the past month, 1 reported two, and 1 child reported five SBEs within the previous month.

Relation between Loss of Control and Eating Disorder Symptomatology

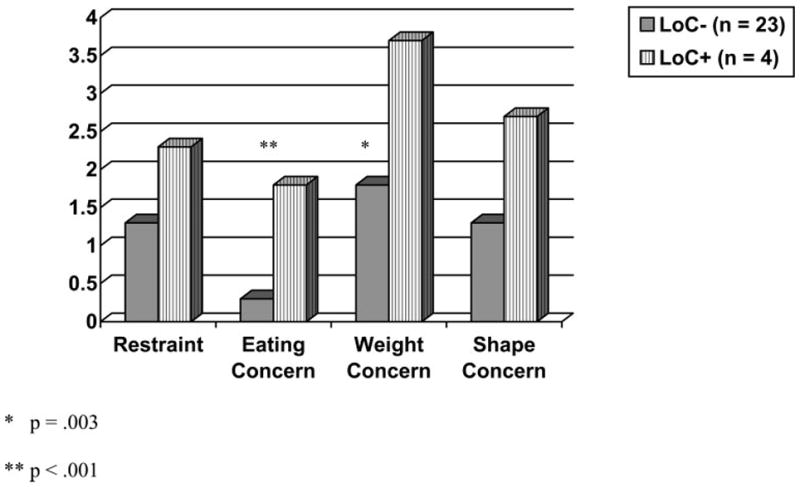

Next, we sought to compare the eating attitudes of children with and without SBEs. As expected, children who endorsed a loss of control over eating reported significantly more eating (p < .001) and weight (p = .003) concerns than did children who had not experienced a loss of control. However, there were no differences in restraint or shape concern (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Eating disorder symptoms among children with (LoC+) and without (LoC−) a loss of control over eating.

Relation between Eating Disorder Symptoms and Treatment Outcome

Sixteen of the 24 (66.7%) children who began treatment completed the family-based behavioral program. Although the numbers are small, 50% (n = 2) of the children with SBEs completed treatment compared with 70% (n = 14) of those without (NS). After controlling for initial, pretreatment weight, children reporting SBEs did not differ from those who did not in the amount of weight lost at posttreatment. However, after controlling for baseline weight, shape concerns were negatively related to weight loss (β = −1.4, t = −3.3, p = .008). That is, children who were more concerned about their shape at baseline had larger decreases in percent over IBW between pretreatment and posttreatment. Although shape concerns were related to short-term weight change, there was no relation between restraint, shape, weight, or eating concerns and weight change between the end of treatment and the follow-up visit 8 months later.

Conclusion

The current study is the first to examine eating-disordered attitudes and behaviors using the ChEDE among severely overweight children seeking treatment. Results indicate that a significant minority (15%) of overweight children reported losing control over eating in the past month. This rate of loss of control, one of the key features of binge eating, is comparable to that reported in the two previous studies that used the ChEDE.8,11 It is important to note, however, that following the guidelines for administration of the ChEDE at the time the current study was conducted, questions about loss of control over eating were only asked to those children who indicated that they had “eaten too much.” Thus, rates of loss of control over eating in this sample may be underestimated. Indeed, 22% (4 of 18) of the children who endorsed having eaten too much at one time reported experiencing a loss of control over their eating.

In addition, two thirds of seriously overweight children presenting for a family-based weight management program indicated that they had “eaten too much at one time” during the past month, and one third denied overeating in the past month. That is, 33% of the children answered no to a question about ever having eaten too much, despite being seriously overweight. These findings highlight the subjective nature of overeating and support the current protocol for administering the ChEDE in which all children are queried about loss of control.8

Compared with equally overweight peers who did not experience a loss of control over eating, children who endorse a loss of control also endorsed more concern about their eating and weight before treatment. In addition, there was trend (p = .06) toward higher shape concerns among those with a loss of control. These findings about eating attitudes and behaviors of children with and without SBEs are similar to results comparing overweight adults with and without BED. Typically, compared with equally overweight individuals who do not binge eat, BED patients report considerably less control over eating, less dietary restraint, and greater fear of weight gain, preoccupation with food, and body dissatisfaction.23,24

This investigation also evaluated the effect of children’s eating attitudes and behaviors on the outcome of a family-based behavioral weight management program. Although the sample size for the current study was small and results should be considered preliminary, loss of control over eating was not associated with weight loss in treatment. If replicated, this finding suggests that, as is the case for adults, loss of control over eating may be relatively common among children who seek behavioral weight control, but does not have an adverse effect on treatment outcome. However, it is also possible that OBEs, which were not reported by any of the children in this sample, would have a greater effect on short-term weight loss. Thus, the relation between binge eating and children and the outcome of behavioral weight management programs warrants further study.

The finding that 50% of the children who reported SBEs before treatment did not finish treatment is intriguing and warrants replication. It may be that the tendency toward increased attrition will not be supported with larger samples. However, it also is possible that the endorsement of loss of control over eating in an overweight child signifies increased distress in general, which may relate to attrition.

Although loss of control over eating does not relate to treatment outcome, a greater degree of concern about body shape at pretreatment is associated with a greater short-term weight loss. Shape concerns are associated with pretreatment weight, such that those with higher concerns weigh more pretreatment. However, the relation between shape concerns and weight loss is apparent even after controlling for weight differences at the start of treatment. Thus, children who feel more dissatisfied with their shape at the start of treatment may be more motivated to lose weight during treatment.

In summary, current findings indicated that overeating is common among seriously overweight children seeking treatment, and a considerable minority reports losing control over their eating in the past month. Moreover, the experience of a loss of control appears to be related to other disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Larger samples are needed to better evaluate the effects of loss of control and other eating disorder attitudes and behaviors on outcome after participation in pediatric weight management programs.

References

- 1.Fairburn CG, Marcus MD, Wilson GR. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge eating and bulimia nervosa: a comprehensive treatment manual. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 361–404. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith DE, Marcus MD, Lewis CE, et al. Prevalence of binge eating disorder, obesity, and depression in a biracial cohort of young adults. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20:227. doi: 10.1007/BF02884965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilfley DE, Friedman MA, Dounchis JZ, et al. Comorbid psychopathology in binge eating disorder: relation to eating disorder severity at baseline and following treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcus MD, Kalarchian MA. Binge eating in children and adolescents. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;34:47. doi: 10.1002/eat.10205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decaluwe V, Braet C, Fairburn CG. Binge eating in obese children and adolescents. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;33:78. doi: 10.1002/eat.10110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson WG, Grieve FG, Adams CD, et al. Measuring binge eating in adolescents: adolescent and parent versions of the Questionnaire of Eating and Weight Patterns. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;26:301. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199911)26:3<301::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgan CM, Yanovski SZ, Nguyen TT, et al. Loss of control over eating, adiposity, and psychopathology in overweight children. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;31:430. doi: 10.1002/eat.10038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, et al. Eating disordered behaviors, body fat, and psychopathology in overweight and normal weight children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:53. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: nature, assessment and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryant-Waugh RJ, Cooper PJ, Taylor CL, et al. The use of the Eating Disorder Examination with children: a pilot study. Int J Eat Disord. 1996;19:391. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199605)19:4<391::AID-EAT6>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Decaluwe V, Braet C. Prevalence of binge eating disorder in obese children and adolescents seeking weight-loss treatment. Int J Obes. 2003;27:404. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcus MD. Binge eating in obesity. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeZwaan M, Mitchell J, Howell L, et al. Characteristics of morbidly obese patients before gastric bypass surgery. Comp Psychiatry. 2003;44:428. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcus MD, Wing RR, Fairburn CG. Cognitive treatment of binge eating versus behavioral weight control in the treatment of binge eating disorder. Ann Behav Med. 1995;17:S909. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reeves RS, McPherson RS, Nichaman MZ, et al. Nutrient intake of obese female binge eaters. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:209. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00055-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wonderlich SA, DeZwaan M, Mitchell JE, et al. Psychological and dietary treatments of binge eating disorder: conceptual implications. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;34:58. doi: 10.1002/eat.10206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jelliffe DB. The assessment of the nutritional status of the community. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rizvi SL, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, et al. Test-retest reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28:311. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200011)28:3<311::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bryant-Waugh RJ, Kaminski Z. Eating disorders in children: an overview. In: Lask B, Bryant-Waugh R, editors. Childhood onset anorexia nervosa and related eating disorders. Hove, UK: Erlbaum; 1993. p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christie D, Watkins B, Lask B. Assessment. In: Lask B, Bryant-Waugh R, editors. Anorexia nervosa and related eating disorders in childhood and adolescence. 2. East Essex, UK: Psychology Press; 2000. p. 105. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epstein LH, Squires S. The stoplight diet for children: an eight-week program for parents and children. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levine MD, Ringham RM, Kalarchian MA, et al. Is family-based behavioral weight control appropriate for severe pediatric obesity? Int J Eat Disord. 2001;30:318. doi: 10.1002/eat.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grilo CM, Masheb RM. Onset of dieting vs. binge eating in outpatients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;24:404. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson GT, Nonas CA, Rosenblum GD. Assessment of binge eating in obese patients. Int J Eat Disord. 1993;13:25. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199301)13:1<25::aid-eat2260130104>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]