Abstract

A growing number of physicians study complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Limited data are available on perspectives of physicians with dual training in conventional medicine and CAM, on issues of communication and collaboration with CAM practitioners (CAMPs). Questionnaires were administered to primary care physicians employed in the largest health maintenance organization (HMO) in Israel and to MD and non-MD CAM practitioners employed by a CAM-related agency of the same HMO. Data for statistical analysis were available from 333 primary care physicians (PCPs) and 241 CAM practitioners. Thirty-one of the 241 CAMPs were dual-trained physicians employed in a CAM-related agency as practitioners and/or triage-consultants. Dual trained physicians and CAMPs shared similar attitudes and supported, more so than PCPs, collaborative physician–CAM practitioner teamwork in clinical practice, medical education and research. Nevertheless, dual trained physicians supported a physician-dominant teamwork model (similar to the PCPs’ approach) in contrast to non-MD CAM practitioners who mainly supported a co-directed teamwork model. Compared to PCPs and non-MD CAM practitioners, dual trained physicians supported significantly more a medical/referral letter as the preferred means of doctor–CAM practitioner communication. Dual trained physicians have a unique outlook toward CAM integration and physician–practitioner collaboration, compared to non-MD CAM practitioners and PCPs. More studies are warranted to explore the role of dual trained physicians as mediators of integration.

Keywords: CAM: complementary alternative medicine, doctor–patient communication, family medicine, integrative medicine, primary care

Background

In the last three decades, the terminology and concept of alternative medicine has gradually shifted toward mainstream medicine. At the same time, a comparable process has shifted conventional medicine from a disease-centered bio-medical paradigm to a more holistic patient-centered approach. Proponents of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) have called for scientific evidence-based research, open-mindedness and respect of non-orthodox models of medical thinking. The term integrative medicine is used by some scholars to refer to the merging of CAM within conventional biomedicine, while others conceptualize it as ‘a higher-order system, or systems, of care that emphasizes wellness and healing of the entire person as primary goals, drawing on both conventional and CAM approaches in the context of a supportive and effective physician-patient relationship’ (1–3).

An increasing number of medical students and physicians worldwide express interest in studying CAM (4–7). In the UK, a survey of 2875 members and fellows of the Royal College of Physicians indicated that 32% of respondents practiced CAM themselves, and 41% referred patients to CAM (8). Limited data are available on MD CAM practitioners’ expectations concerning integrative medicine and their perspectives of communication and collaboration with non-MD CAM practitioners. An-Fu Hsiao et al. examined attitudes of CAM practitioners (CAMPs) (acupuncturists and chiropractors), physicians and physician acupuncturists toward integration and suggested that ‘dual trained’ practitioners exemplified clinicians with a greater orientation toward integrative medicine (9).

The prospect of emerging integrative initiatives in medical practice raises a number of significant questions concerning the role of MD CAM practitioners: what are dual-trained MD CAM physicians’ perspectives concerning integration in clinical practice, as well as medical research and education? Do they have similar or different perspectives compared to the ‘conventional’ physician or non-MD CAM practitioner? How do they envision conventional and CAM integration in daily practice? Do they have a special role in making integration feasible?

In order to address some of these questions the research team conducted a study, which aimed to explore attitudes of primary care physicians (PCPs), and MD/non-MD CAM practitioners employed by the largest health maintenance organization in Israel.

Research Design and Methods

Study Sites and Participants

This two-arm study included PCPs and CAMPs employed by Clalit Health Services (CHS) in Israel. CHS is the largest of four health maintenance organizations (HMO) in Israel, serving 3 800 000 clients (∼60% of the population) (10). CHS operates a related agency that offers reduced price CAM services at 40 clinics throughout the country. Most of these services are available at secondary care clinics and operate independently of the conventional system, with a distinct administrative and clinical organization. Most patients are self-referred to the CAM clinic, and their costs are partly reimbursed by the CHS if they have additional medical insurance coverage. All patients must be evaluated by the clinic physician prior to CAM treatment. Dual trained physicians (trained in conventional and complementary medicine) act as triage-consultants who screen and then refer patients to different CAM treatments and/or CAM clinicians.

Study Design

This study was based on the authors’ educational, clinical and research experience with PCPs, CAM students/practitioners and patients in conventional and CAM settings. A preliminary questionnaire was developed based on focus group discussions with of PCPs and CAMPs. A refinement of the questionnaire was performed on the basis of the focus groups’ appraisals.

The authors decided to use a broad and understandable definition of CAM: ‘therapies often named alternative, complementary, natural, folk/traditional medicine, which are not usually offered as part of the medical treatment in the clinic’. Added to this definition was a list of CAM modalities: herbal medicine, Chinese medicine (including acupuncture), homeopathy, folk and traditional medicine, diet/nutritional therapy (including nutritional supplements), chiropractic, movement/manual healing therapies (massage, reflexology, yoga, Alexander and Feldenkreis techniques, etc.), mind-body techniques (meditation, guided imagery, relaxation), energy and healing therapies and other naturopathic therapies. The Questionnaires were administered by post or e-mailed to 2532 primary care practitioners and 450 CAMPs employed in Clalit Health Organization.

Data Analysis

The data were evaluated by SPSS software, version 12 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA). A level, significantly lower than 0.05, was regarded as important. Pearson Chi-Square and Fisher's exact T-tests were used for detecting the differences in the prevalence of categorical variables and demographic, collaborative and integrative variables among the three groups PCPs versus MD and non-MD CAM practitioners).

A T-test was performed to determine whether there is a difference among the groups in the continuous variables.

Results

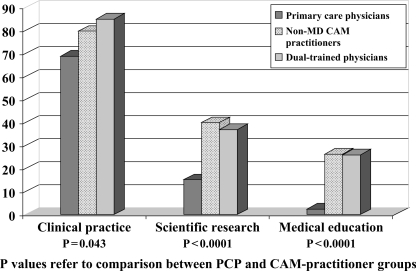

Data for statistical analysis were available from 333 PCPs and 241 CAMPs of whom 31 (13%) were dual-trained physicians. Demographics and characteristics of participants are specified in Table 1. Attitudes of PCPs, CAMPs and dual-trained physicians were compared concerning interest in teamwork collaboration in the arenas of clinical practice, research and education (Fig. 1). Dual-trained physicians did not differ from the total CAM practitioner group. Compared to PCPs, CAMPs supported doctor-practitioner collaboration significantly more in clinical practice (77% versus 69% P = 0.043), scientific research (42% versus 15% P<0.0001) and medical education (27% versus 2% P<0.0001).

Table 1.

Demographic and characteristics of participants

| CAM practitioners | Dual trained physicians subgroup | Primary care physicians | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 241 | 31 | 333 |

| Sex—male : female (%) | 95 : 137 (41 : 59) | 20 : 10 (67 : 33) | 187 : 134 (58 : 42) |

| Mean age in years ± SD (median) | 40 ± 9.4 (38) | 46.8 ± 7.15 (46) | 47.7 ± 7.2 (48) |

| Medical specialty or CAM modality, n (%)a | Movement/Manual healing 124 (51%) Traditional Chinese medicine 88 (37%) Naturopathy 29 (12%) Homeopathy 10 (4%) Herbal medicine 9 (4%) Chiropractice 8 (3%) Healing 4 (2%) Meditation 3 (1%) | Several CAM modalities 15 Homeopathy 7 Traditional Chinese medicine 3 Meditation 3 Herbal medicine 1 Naturopathy 1 | 265 specialists (86%)a: Family medicine 105 (52%) Internal medicine 47 (23%) Pediatrics 9 (4.5%) |

aEighty-seven (27%) of PCPs had studied various also undergone CAM training. Twenty-four (7%) of PCPs had studied various CAM courses.

Figure 1.

In which areas are you interested in conventional–CAM collaborative teamwork?

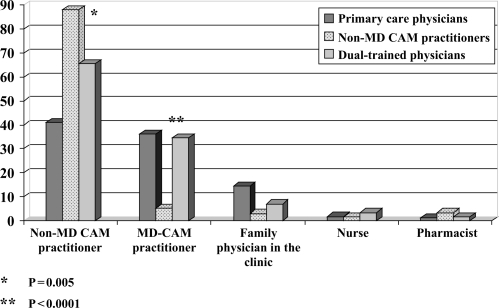

Dual-trained physicians and non-MD CAM practitioners also had similar attitudes when asked about their perception of potential integration of CAM in a primary care clinic. Compared to PCPs, both groups attributed a major role to family physicians as the referral source in a hypothetical integrative clinic (82% versus 63% P<0.0001). Nevertheless, dual-trained physicians envisioned a more important role for MD CAM practitioners in providing CAM treatment in such an integrative primary care setting (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

If CAM was provided in a primary care clinic, who should offer CAM treatment?

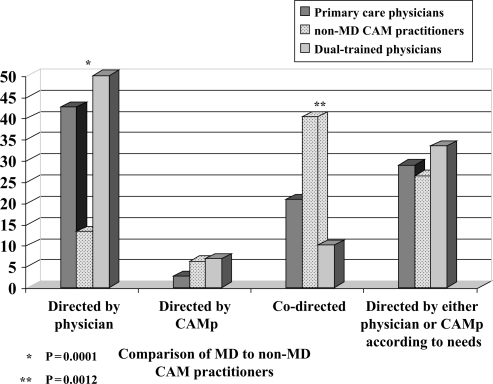

Figure 3 shows significant differences in dual-trained physicians’ and non-MD CAM practitioners’ attitudes to four theoretical models of physician-CAM practitioner teamwork. Both PCPs and dual-trained physicians were significantly more supportive of teamwork directed and co-ordinated by a physician (P = 0.0001). On the other hand, non-MD CAM practitioners were much more supportive of a co-directed model (non-MD CAM practitioners: 40.3% versus dual-trained physicians 10% P = 0.0012).

Figure 3.

How do you perceive conjoint physician-CAM practitioner teamwork?

Compared to non-MD CAM practitioners, dual-trained physicians reported having significantly more experience in communication with the physician treating the same patient (93% versus 57% P<0.0001). Dual-trained physicians supported, more so than PCPs and CAMPs, a referral/medical letter as the best route of communication with physicians (P = 0.04 in a comparison of dual-trained physicians to the other groups).

Discussion

This study suggests that dual-trained physicians have unique outlook concerning CAM integration compared to non-MD CAM practitioners and PCPs. Both dual-trained physicians and non-MD CAM practitioners share similar attitudes toward CAM integration. However, they differ in their attitude toward practical realization of physician–CAM practitioner teamwork. Dual-trained physicians, as well as PCPs, envision dominant and leading role of physicians in physician–practitioner teamwork, while non-MD CAM practitioners support a co-directed model. This attitude discrepancy between physicians and practitioners may be influenced by physicians’ wish to hold responsibility based on Israel's medical liability laws. Nevertheless, physicians’ attitude toward interdisciplinary teamwork may be influenced by other factors as well that may include underestimation of non-physician practitioners. Fletcher et al. compared physicians’ and nurse practitioners’ views of the role of nurse practitioners as providers of primary care and found that most of the physician respondents did not think nurses could provide adequate primary care and envisioned nurses’ role merely as a physician extender (11). The authors concluded that in order to facilitate interdisciplinary teamwork there is need to clarify roles, monitor quality of care of both MDs and nurse practitioners, and provide feedback to all concerned. These insights concerning team building and interdisciplinary collaboration may be implemented in the teamwork setting of MD and non-MD CAM practitioners. Future studies may examine physicians’ and practitioners’ attitudes toward collaborative case management in light of legal, ethical and organizational aspects as well as patients’ expectations of doctor–CAM practitioner collaboration. Furthermore, it is advisable to study prospectively possible evolution of MDs’ and non-MDs’ attitude change in integrative setting based on gradual increase of personal and professional acquaintance and confidence.

This study also illustrates the nearly similar attitudes of dual-practitioners and PCPs concerning the role of MD CAM practitioners as providers of CAM in primary care (Fig. 2). Althogh dual practitioners are much receptive toward integration and collaboration with CAM practitioners, compared to PCPs, they emphasize more the physician role in integration. In other words, dual-practitioners (MDs) support integration as do CAMPs but when they envision the practical realization of integration they act as ‘physicians’. This discrepancy between MD and non-MD CAM practitioners’ viewpoints may have several reasons. First, MD CAM practitioners experienced in both worlds may have more realistic experience-based insight on the limits and prospects of integrative medicine. Second, they are possibly more aware to the abilities and limitations of CAMPs with whom they currently collaborate on limited basis.

This study also shows that dual-trained physicians may have a pivotal role in formation of physician–practitioner communication. Based on their experience in communication with other physicians, they indicate that a referral/medical letter is the most practical tool to advance doctor–CAM practitioner communication. Further studies might explore whether writing referral/medical letters actually advances doctor–practitioner communication and whether this should be an obligatory requirement. Furthermore, studies need to explore the needed features of such medical letter in terms of content, ethics and terminology. Construction of universally accepted terminology is challenging in view of the language gap between the conventional and CAM schools of thought (12). Dual-trained physicians may potentially serve as mediators of such a process, being familiar with the terminology of the two worlds. Dual-trained physicians may not only advance doctor–practitioner collaboration but also act as mediators for better communication in the triangle of patients, physicians and CAMPs. Dual-trained physicians may actively induce doctor–practitioner dialogue by suggesting patients to ask their conventional physician and CAMPs for a referral/medical letter. Patients may identify dual-trained physicians as practitioners who can place their feet in both worlds, and have the authority to advice on doctor–practitioner communication.

This study has several limitations that include the small size group of 31 dual trained. This group may represent physicians who are more keen toward integration although this selection bias potential is limited, since they are all employed in the same CAM medical organization affiliated with a conventional HMO. Another limitation is the discrepancy in the groups’ response rate [PCPs 13% (333/2532) versus CAMPs 53% (241/450)]. A possible reason for the low response rate of PCPs may have been caused by their low interest or disagreement with CAM compared to CAMPs who as expected find interest in CAM research. The study results should be cautiously interpreted in view of the fact that the response rates difference may reflect a selection bias in the PCP group. Nevertheless, the similarity of PCPs’ and MD CAM practitioners’ attitudes suggest the reliability of the data and provide insight into the role of CAM-trained physicians in future integrative models in the community.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Dr Moshe Scharf, medical director of Clalit Mashlima—Complementary Clalit Health Services—for his support and collaboration with the team of researchers, Dr Chen Shapira, medical director of CHS, Haifa District, for her generous support and encouragement,

Ronit Leiba for the statistical analysis, Hamichlala Leminhal for financial support of the statistical work-up, Anat Klein N.D., Dalia Vardi and Danit Steinberg from the International Center and College of Natural Complementary Medicine, Dr Moshe Frenkel for his important contribution in conceptualizing the research methodology and Marianne Steinmetz for editing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bell IR, Caspi O, Schwartz GE, Grant KL, Gaudet TW, Rychener D, et al. Integrative medicine and systemic outcomes research: issues in the emergence of a new model for primary health care. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:133–40. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weil A. Integrated medicine. Imbues orthodox medicine with the values of complementary medicine. Br Med J. 2001;322:119–20. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenthal DS, Dean-Clower E. Integrative medicine in hematology/oncology: benefits, ethical considerations, and controversies. Hematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program) 2005;1:491–7. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2005.1.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenfield SM, Brown R, Dawlatly SL, Reynolds JA, Roberts S, Dawlatly RJ. Gender differences among medical students in attitudes to learning about complementary and alternative medicine. Complement Ther Med. 2006;14:207–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeo AS, Yeo JC, Yeo C, Lee CH, Lim LF, Lee TL. Perceptions of complementary and alternative medicine amongst medical students in Singapore – a survey. Acupunct Med. 2005;23:19–26. doi: 10.1136/aim.23.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oberbaum M, Notzer N, Abramowitz R, Branski D. Attitude of medical students to the introduction of complementary medicine into the medical curriculum in Israel. Isr Med Assoc J. 2003;5:139–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milden SP, Stokols D. Physicians’ attitudes and practices regarding complementary and alternative medicine. Behav Med. 2004;30:73–82. doi: 10.3200/BMED.30.2.73-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewith GT, Hyland M, Gray SF. Attitudes to and use of complementary medicine among physicians in the United Kingdom. Complement Ther Med. 2001;9:167–72. doi: 10.1054/ctim.2001.0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsiao AF, Ryan GW, Hays RD, Coulter ID, Andersen RM, Wenger NS. Variations in provider conceptions of integrative medicine. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:2973–87. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clalit Health Services. ( http://www.microsoft.com/israel/casestudies/clalit_sql.mspx) (date last accessed May 25, 2007)

- 11.Fletcher CE, Jill Baker S, Copeland LA, Reeves PJ, Lowery JC. Nurse Practitioners’ and Physicians’ Views of NPs as Providers of Primary Care to Veterans. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39:358–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caspi O, Bell IR, Rychener D, Gaudet TW, Weil AT. The Tower of Babel: communication and medicine: an essay on medical education and complementary-alternative medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3193–5. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]