SUMMARY

The sense of balance depends on the intricate architecture of the inner ear, which contains three semicircular canals used to detect motion of the head in space. Changes in the shape of even one canal cause drastic behavioral deficits, highlighting the need to understand the cellular and molecular events that ensure perfect formation of this precise structure. During development, the canals are sculpted from pouches that grow out of a simple ball of epithelium, the otic vesicle. A key event is the fusion of two opposing epithelial walls in the center of each pouch, thereby creating a hollow canal. During the course of a gene trap mutagenesis screen to find new genes required for canal morphogenesis, we discovered that the Ig superfamily protein Lrig3 is necessary for lateral canal development. We show that this phenotype is due to ectopic expression of the axon guidance molecule Netrin1 (Ntn1), which regulates basal lamina integrity in the fusion plate. Through a series of genetic experiments, we show that mutually antagonistic interactions between Lrig3 and Ntn1 create complementary expression domains that define the future shape of the lateral canal. Remarkably, removal of one copy of Ntn1 from Lrig3 mutants rescues both the circling behavior and the canal malformation. Thus, the Lrig3/Ntn1 feedback loop dictates when and where basement membrane breakdown occurs during canal development, revealing a new mechanism of complex tissue morphogenesis.

Keywords: inner ear, morphogenesis, vestibular system, Netrin, Lrig, basement membrane

INTRODUCTION

Precise spatiotemporal regulation of intercellular signaling is critical for molding tissues into three-dimensional structures during organogenesis. One of the most striking examples of tissue morphogenesis is the development of the three-dimensional architecture of the inner ear, which houses the sensory organs for hearing and balance. Angular acceleration is detected by three fluid-filled semicircular canals that are oriented with respect to the three dimensions of space. Changes in head position result in fluid movement within the canals, thereby activating specialized hair cells in the sensory epithelia located at the base of each canal. Subsequently, vestibular ganglion neurons convey signals from the sensory epithelium to the central nervous system. The inner ear is a small, intricately-shaped organ that does not tolerate even subtle changes to its structure; indeed, even the slightest perturbations in the structure of the vestibular canals can result in debilitating dizziness, vertigo, and abnormal posture in humans (Sando et al., 2001; Sando et al., 1984).

Morphogenesis of the inner ear is set in motion by early patterning events, which result in the expression of key cell fate determinants within discrete domains of a primordial structure. The inner ear is sculpted from a simple ball of epithelium called the otic vesicle (Fig. 1) (Fekete, 1999). The semicircular canals are derived from two outpocketings, the canal pouches, which are specified by transcription factors such as Otx1 and Dlx5 (Merlo et al., 2002; Morsli et al., 1999). A critical event in canal development is the formation of the fusion plate in the center of the pouch. During this process, the basement membrane breaks down, allowing signaling molecules to induce proliferation in the surrounding mesenchyme and the two epithelial walls to come together (Martin and Swanson, 1993; Pirvola et al., 2004; Salminen et al., 2000; Streeter, 1907). At the same time, fusion plate cells lose their columnar morphology and intercalate to form a single layer of cells (Martin and Swanson, 1993). Importantly, these changes in cell morphology and basal lamina integrity occur only in the vicinity of the fusion plate. In contrast, the epithelium in the perimeter of the pouch remains intact and will eventually form the walls of the mature canal. Hence, the final shape of each canal is determined by when and where fusion occurs.

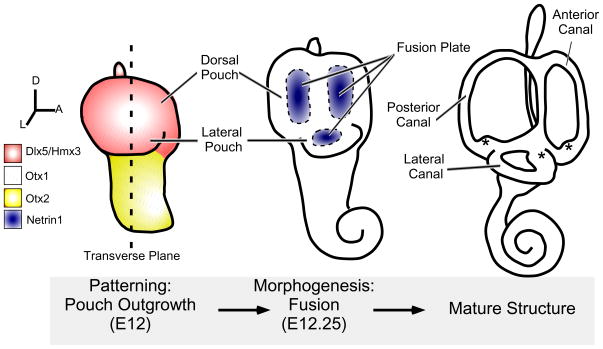

Fig. 1. Patterning and Morphogenesis of the Inner Ear.

Diagrams of the transformation of the otic vesicle into the mature structure of the inner ear. Early in development (left), the axes of the otic vesicle are patterned, with the presumptive vestibular system expressing Dlx5 and Hmx3 (red) and the developing cochlea expressing Otx2 (yellow). The lateral pouch is defined by expression of Otx1 (blue dots). A few hours later, during morphogenesis, discrete regions in the dorsal and lateral pouch begin to transcribe Netrin1 (blue, middle). These regions will subsequently undergo fusion and disappear, leaving the epithelium in the perimeter to form the walls of the mature canals (right). Motion is detected by hair cells housed in swellings at the base of each canal called ampullae (*). In all of the following figures, paintfilled inner ears are shown looking down onto the lateral canal, with anterior to the right, while sections through the otic vesicle are in the transverse plane (as indicated), with dorsal up and lateral to the right.

A key regulator of fusion is the laminin-related molecule Netrin1 (Ntn1). In Ntn1 mutant mice, the inner ear fails to acquire its mature shape due to an arrest in canal morphogenesis (Salminen et al., 2000). Although best characterized for its function as a secreted chemoattractant for axons during neuronal development (Moore et al., 2007), Ntn1 is also critical for many aspects of tissue morphogenesis, including cell migration and local cell adhesion (Srinivasan et al., 2003; Yebra et al., 2003). In the inner ear, Ntn1 is required for breakdown of the basement membrane surrounding the fusion plate (Salminen et al. 2000). Ntn proteins are localized to the basal lamina (Salminen et al., 2000; Schneiders et al., 2007) and can bind to collagen and laminin in vitro (Schneiders et al., 2007; Yebra et al., 2003), but how Ntn1 signaling promotes basal lamina breakdown remains unclear (Matilainen et al., 2007).

Despite abundant evidence that Ntn1 is a powerful morphogen, little is known about the pathways that restrict Ntn1 expression to highly limited spatiotemporal domains in any developing system (Kennedy, 2000). In addition to its functions during development, Ntn1 is overexpressed in several human cancers (Fitamant et al., 2008; Link et al., 2007), underscoring the importance of understanding how expression of Ntn1 is regulated.

Here, we demonstrate that Ntn1 expression is controlled by cross-repressive interactions with the Ig superfamily protein Lrig3 that define the boundary between the fusing and non-fusing regions of the lateral canal pouch. This novel feedback loop dictates when and where basement membrane breakdown occurs, thereby ensuring that the inner ear acquires its precise three-dimensional shape.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Mice

The LST016 gene trap line was previously reported (Leighton et al., 2001; Mitchell et al., 2001). The mice have been maintained for >5 generations on the C57Bl6/J background. Genotyping was performed using the following primers: LST016F (GAGGTGCCTGATGCTTAAGTT TCG); LST016R (TTCAACCTTGGCTTCCAATGTCCA); and GTR7 (CAAGTCTATCCTAGGGAAAGGGTC) which is specific to the Lrig3LST016 gene trap vector pGT2TMPFS. The Lrig3flox conditional allele was produced via homologous recombination using a targeted construct with LoxP sites surrounding the ATG-containing exon1. Heterozygous mice were produced by germline Cre-excision using a global deleter line (Schwenk et al., 1995). Genotyping was performed using the following primers VEA303 (CGGAATTTCCTACAATCTCAGC); VEA304 (GTGCTCCTGGTGGCTCAGT); VEA305 (CCCCCTCCAATTTTAACAAA). The Ntn1 gene trap line was previously reported (Serafini et al., 1996). The mice have been maintained for >5 generations on the C57Bl6/J background. Genotyping was performed using the following primers: pGT1_8TM3021R (GTTGCACCACAGATGAAACG); pGTEn2_1723 (TCCCGAAAACCAAAGAAGAAG); and pGT1_8TM1743 (GAACCCTAACAAAGAGGACAAG). The described genotyping screen allows for the detection of the Ntn1-specific gene trap vector pGT1.8TM. Heterozygous and mutant genotypes were confirmed by evaluating the thickness of the ventral commissure in the neural tube following BIII-Tubulin and Neurofilament immunostaining on cryosectioned embryos. These two gene trap lines are annotated as Lrig3+/− or Ntn1+/− for the heterozygous condition and Lrig3−/− or Ntn1−/− for the mutant condition. Unc5hb mutant mice were maintained on a CD1 background and genotyped as described (Lu et al., 2004). The Integrin a6 gene trap mice (Mitchell et al., 2001) were maintained on a C57Bl6/J background and were genotyped using the following primers: LST045F5 (GCCCAAATCCCTTGTGTATG); LST045R1 (ACCCACAGCAACCTTTGTTC); and GTR3 (TCTAGGACAAGAGGGCGAGA). The mice were maintained in accordance with institutional and NIH guidelines approved by the IACUC at Harvard Medical School and the University of Virginia.

Quantitative PCR

cDNA was made from total mouse E11.5 embryonic RNA using random primers. Lrig3 was amplified as described (Abraira et al., 2007) with SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad) and primers flanking the Lrig3 exon3/4 boundary: VEA48 (GAACAACAATGAATTAGAGACCATTC) and VEA49 (AGGGTGGAAAGGCA-GTTCTC). Levels were normalized based on amplification of GAPDH from the same samples: GAPDHe-F (CTCATGACCACAGTCCATGC), GAPDHe-R (GCACGTCAGATCC-ACGAC). Loss of Lrig3 message from Lrig3 null mice was confirmed by RT-PCR amplification of E12.5 embryonic cDNA using primers VEA48 and VEA49.

Paintfilling

E12–E14 embryos were fixed overnight at 4° C with Bodian’s Fix, dehydrated overnight at RT with 100% EtOH, then cleared overnight at RT with methyl salicylate. Heads were hemisected, and white latex paint (Benjamin Moore) diluted to 0.025% in methyl salycilate was injected into the cochlea with a pulled glass pipette and a Hamilton syringe filled with glycerol.

In situ hybridization

Non-radioactive in situ hybridization was performed on 10–12 μm cryosections using the following probes: Ntn1 (NM_008744), Otx1 (NM_011023), Otx2 (NM_144841), Dlx5 (NM_010056), Hmx3 (NM_008257). A detailed protocol is available at http://neuro.med.harvard.edu/site/goodrichweb/.

X-gal and PLAP staining

Staining for β-galactosdiase and alkaline phosphatase activity was performed as described (Leighton et al., 2001) except that 10–20 μm frozen sections were used, and the tissue was fixed for 1 hour at 4° C.

Immunohistochemistry

E12 embryos were collected and fixed for 1–2 hrs at 4° C in 4%PFA/PBS and then dehydrated in 30% sucrose/PBS overnight at 4° C. Embryos were then embedded in Neg50 (Richard-Allan Scientific). 5–10 μm cryosections were blocked and permeabilized in 5%Normal Donkey Serum + 2% BSA + 0.1% Triton X-100 for 1 hour at RT. Primary antibodies were added in above block, without Triton X-100, overnight at 4° C at the following concentrations: CollagenIV (1:200, Abcam, ab6586); Pan-mouse laminin (1:250, Chemicon, AB2034); BIII-Tubulin (1:1000, Covance, PRB-435P); and Neurofilament (1:500, DSHB, SH3). The following day, the sections were incubated in secondary antibody (1:2000, Alexa Fluor488 or 568, Jackson Immunoresearch) in block, without Triton X-100. All sections were counterstained with DAPI (1:10,000).

Histology and Electron Microscopy

Plastic semi-thin (1 μm) and ultra-thin (90 nm) sections for light and electron microscopy studies were obtained with the help from the Harvard Medical School Electron Microscopy Facility (www.cellbio.med.harvard.edu/research_facilities).

RESULTS

Identification of Lrig3 as a new regulator of inner ear morphogenesis

To gain insight into the molecules that drive inner ear morphogenesis, we took advantage of the fact that even subtle changes in the structure of the inner ear cause dramatic behavioral defects. Candidate genes were identified by screening a large set of mice generated by gene trap technology (Leighton et al., 2001; Mitchell et al., 2001). Upon insertion into the intron of a gene, the gene trap vector simultaneously blocks transcription and reports the normal expression pattern of that gene through a β-galactosidase reporter (Fig. 2A). X-gal-stained heterozygous embryos were examined to find genes expressed in restricted domains of the otic vesicle prior to morphogenesis, and then homozygous mutants for the best candidate genes were assessed for defects in hearing and balance.

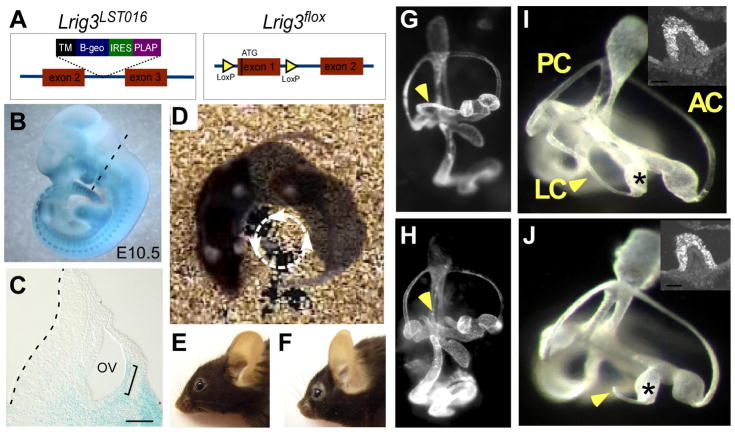

Fig. 2. Lrig3 mutant mice exhibit circling behavior due to a truncation of the lateral semicircular canal.

(A) Diagrams of two independent alleles of Lrig3 illustrating insertion of the gene trap vector in LST016 mice (left) and the introduction of LoxP sites on either side of the ATG-bearing exon in the conditional Lrig3flox allele (right). (B,C) X-gal detection of the Lrig3-β-geo fusion protein in an E10.5 Lrig3 heterozygous embryo (B) and in sections through the otic vesicle (C) in the plane indicated (dotted line, B). β-galactosidase activity is high in somitic mesoderm, the branchial arches and the limb buds. In the developing inner ear, transcription of Lrig3 is enriched in the lateral otic epithelium by E10.5 (bracket). Scale bar: 50 μm. (D) A single Lrig3 mutant mouse photographed in three points of its circling trajectory. (E,F) Lrig3 homozygotes (F) have shortened snouts compared to heterozygotes (E). (G–J) Paintfilled inner ears of E14 Lrig3 +/− (G,I) and −/− (H, J) embryos. Low magnification views of the entire inner ear (G,H) reveal a truncation of the lateral semicircular canal (arrowhead, H). Other structures appear normal in size and shape. High magnification views of the vestibular apparatus confirm truncation of the lateral canal (LC) but not the anterior (AC) or posterior (PC) canals. The lateral ampullae (asterisks) are unaffected, with no change in the number or distribution of MyosinVIIa-positive hair cells in the lateral cristae (insets). Dorsal is up; posterior is to the left.

In this screen, we identified a strain of mice, LST016, with β-galactosidase activity in the lateral wall of the otic vesicle (Fig. 2B,C), a region fated to give rise to the lateral semicircular canal (Fekete and Wu, 2002). Homozygous mutants exhibit circling and head tossing behaviors, consistent with the presence of an inner ear defect (Fig. 2D). Visualization of the three-dimensional structure of the vestibular apparatus revealed a fully penetrant truncation of the lateral semicircular canal in homozygotes (Fig. 2G-J). Histological studies confirmed that the canal epithelium is missing as early as E13 (data not shown). The lateral ampulla is unaffected, and the sensory epithelium is properly innervated, as determined by MyosinVIIa and Neurofilament immunostaining (Fig. 2I,J and data not shown). Although the reporter is also active in the developing cochlea (Supp. Fig. 1H), the mice develop normal hearing as assessed by auditory brainstem response (ABR) assays (Supp. Fig. 2). All mutants also display craniofacial deformities and a dramatically shortened snout (Fig. 2E,F).

LST016 mice carry an insertion of the pGT2TMPFS gene trap vector in the third intron of the Lrig3 gene (Fig. 2A), causing a truncation of the wild-type transcript and fusion of the β-galactosidase reporter protein to Lrig3 at amino acid 126 (Mitchell et al., 2001). Lrig3 is one of three members in a family of single-pass transmembrane proteins containing 15 leucine rich repeats (LRR) and three immunoglobulin (Ig) domains in the extracellular domain and intracellular tails that vary in length and composition (Guo et al., 2004; Hedman and Henriksson, 2007). Quantitative RT-PCR of homozygous Lrig3 tissue (n=4 embryos) detected only 3.05 ± 1.59 % of the wild-type transcript, indicating that the phenotype is severely hypomorphic. To confirm that the phenotype is due to a loss of Lrig3, a null allele was made by flanking the ATG-bearing exon of Lrig3 with LoxP sites (Fig. 2A). After germline Cre-mediated excision, no Lrig3 messenger RNA remained (data not shown). Null mutant mice exhibit the same lateral canal and craniofacial defects evident in the gene trap allele (data not shown), demonstrating that the phenotypes reflect a complete loss of Lrig3 function.

Truncation of the lateral semicircular canal in Lrig3 homozygotes is due to early and ectopic fusion

The semicircular canals develop from two epithelial outpocketings called canal pouches, with the anterior and posterior canals arising from the dorsal pouch and the lateral canal forming from the lateral pouch (Fig. 1). Early patterning events that define the axes of the otic vesicle result in restricted expression of transcription factors that specify the two pouches. Because Lrig3 expression is restricted to the lateral pouch during these early patterning stages, it seemed possible that Lrig3 acts in a signaling pathway that ensures restricted expression of transcription factors required for specification of the lateral canal. To test this, we examined the expression patterns of Otx1, Otx2, Hmx3, and Dlx5, transcription factors required for normal development of the vestibular system (Merlo et al., 2002; Wang et al., 1998). However, Lrig3 mutant embryos exhibited no obvious changes in early gene expression, indicating that the lateral pouch is specified in the right place and at the right time (Supp. Fig. 3).

Since canal patterning was unaffected, we asked whether subsequent morphogenesis events proceed normally in Lrig3 mutant embryos. We visualized pouch outgrowth and fusion by paintfilling inner ears between E11.5 and E12.5 (Fig. 3). The precise stage of canal development was determined by evaluating the extent of fusion in the anterior and posterior canals, which develop earlier than the lateral canal (Martin and Swanson, 1993). In control embryos, the lateral pouch grows out at E12 and fusion begins at E12.5 (Fig. 3A-C). No changes in the size or shape of the early canal pouch occur in E12 Lrig3 mutant embryos, consistent with correct patterning of the otic vesicle (Fig. 3D). However, fusion in the lateral pouch begins several hours earlier than normal and over a larger area, extending to the perimeter of the lateral pouch epithelium (Fig. 3E). The lateral canal is truncated by E12.5, when fusion is just beginning in wild-type littermates (Fig. 3F). Thus, fusion is expanded and accelerated in Lrig3 mutants.

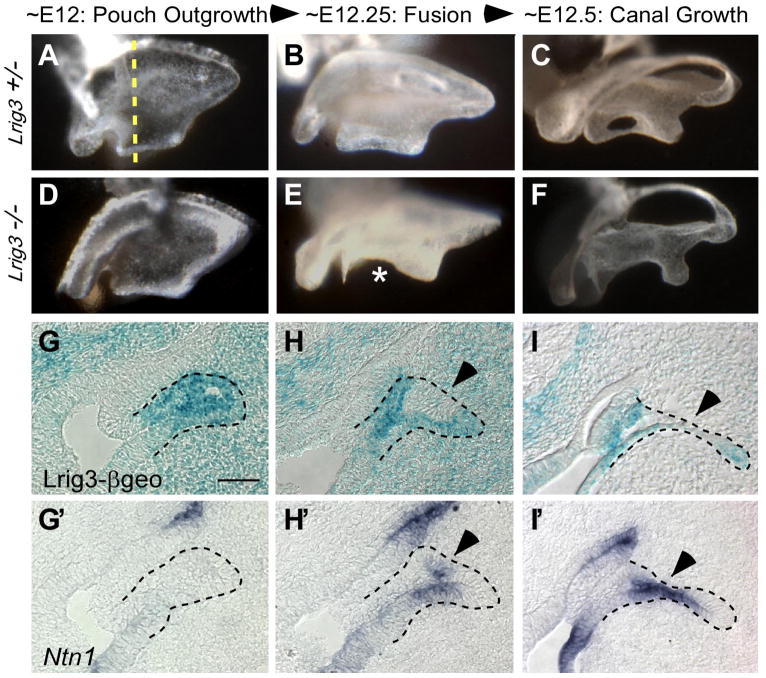

Fig. 3. Lrig3 acts in the non-fusing epithelium to prevent premature and ectopic fusion.

(A–F) Dorsal views of paintfilled Lrig3 +/− (A–C) and −/− (D–F) inner ears collected at 6 hour intervals from E12 to E12.5. Anterior is to the right. In mutants, early outgrowth is normal (D). However, fusion initiates too early (E) and occurs over a larger area (asterisk) than in control embryos (B,C), resulting in truncation by E12.5 (F). (G–I) Adjacent sections of Lrig3 heterozygotes through the lateral pouch at the level indicated (dashed line, A) were processed for β-galactosidase histochemistry to reveal Lrig3-βgeo activity (G–I) or for in situ hybridization with a probe to Ntn1 (G′–I′). Lrig3 is transcribed throughout the lateral pouch prior to fusion (G). Levels become reduced (H) in the nascent fusion plate (arrowhead) just as Ntn1 expression initiates here (H′). Lrig3 expression is further diminished (I) as transcription of Ntn1 expands (I′).

Lrig3 and Ntn1 act in complementary domains to regulate basal lamina integrity

While fusion occurs prematurely in Lrig3 mutants, fusion is arrested in Ntn1 mutants, raising the possibility that these two genes cooperate to determine the timing and extent of fusion. To gain more insight into the relationship between Lrig3 and Ntn1 during canal morphogenesis, we compared their expression patterns on adjacent sections from E12 to E12.5. We found that Lrig3 expression is enriched in the lateral pouch epithelium during the canal pouch outgrowth stage, when Ntn1 is not yet expressed (Fig. 3G,G′). Then, just before fusion begins, Lrig3 expression becomes reduced in the center of the pouch (Fig. 3H), concomitant with the initiation of Ntn1 transcription in the nascent fusion plate (Fig. 3H′). As fusion progresses, the domain of Ntn1 transcription expands (Fig. 3I′), while Lrig3 is downregulated in Ntn1-positive cells (Fig. 3I) but is maintained in the surrounding, non-fusing epithelium. After the canal is fully formed, Lrig3 and Ntn1 continue to be expressed in non-overlapping domains of the canal epithelium (data not shown). Hence, consistent with their opposing activities during canal development, Lrig3 and Ntn1 are expressed in complementary domains of the lateral pouch.

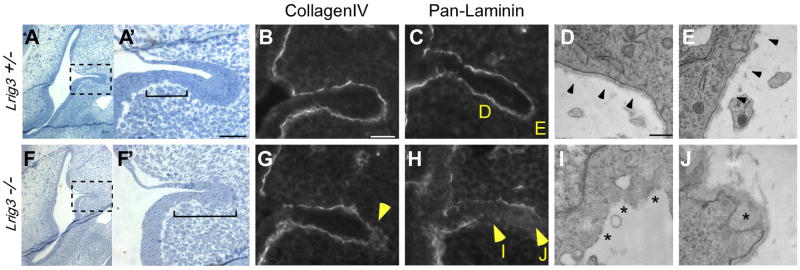

These results suggest that Lrig3 is required in the non-fusing epithelium to prevent fusion from occurring by balancing the activity of Ntn1 in the fusion plate. Malformation of the semicircular canals in Ntn1 mutant mice is preceded by a failure in basement membrane breakdown (Salminen et al., 2000). Therefore, we asked whether the early and ectopic fusion event in Lrig3 mutant mice is also accompanied by changes in the integrity of the basal lamina that normally separates the epithelium from the surrounding mesenchyme. We found that dramatic changes occur in the basal lamina of Lrig3 mutant embryos. In control embryos, laminin and collagen networks are intact prior to fusion plate formation, as shown by immunostaining and electron microscopy analysis (Fig. 4A-E). In contrast, in Lrig3 mutants, the basal lamina is missing or disrupted throughout the lateral pouch, including regions where fusion normally never occurs (Fig. 4F-J). Moreover, the otic epithelium throughout the lateral pouch is abnormally thin, such that even cells in the perimeter of the pouch resemble fusion plate cells (Fig. 4A′,F′). Neither Caspase-3 immunostaining (Supp. Fig. 4) nor electron microscopy analysis (data not shown) revealed an increase in apoptosis, suggesting that these morphological changes are not associated with cell death. Thus, Lrig3 inhibits basement membrane breakdown in the non-fusing epithelium.

Fig. 4. The basement membrane undergoes early and ectopic breakdown in the inner ear of Lrig3 mutant mice.

(A,F) Transverse plastic sections through inner ears of E12 Lrig3 +/− (A) and −/− littermates (F), with magnified views of the boxed areas (A′, F′). Dorsal is up; lateral is to the right. In controls, epithelial cells in the fusion plate intercalate to form a single layer of cells (A′), but in mutants, this region is expanded (brackets, F′). Scale bar: 50 μm. (B, C, G, H) Immunofluorescent detection of Collagen IV (B,G) and all laminins (C, H) in E12 +/− (B,C) and −/− embryos (G,H) sectioned in the transverse plane. In homozygotes, the basal lamina is disturbed by breaks in the laminin network and ectopic accumulation of Collagen IV (arrowheads, G, H). (D, E, I, J) Electron micrographs of the regions indicated in C and H. The basement membrane is continuous in heterozygotes (arrowheads, D, E) but is absent (asterisks, I) or severely disrupted (asterisk, J) in homozygotes. Scale bar: 500 nm.

Ntn1-dependent basal lamina breakdown does not require known receptors

To understand the molecular basis of the basement membrane phenotype, we explored the possibility that Lrig3 modulates Ntn1 activity by regulating one of its known receptors. This hypothesis is supported by the facts that Lrig3 is expressed complementary to Ntn1 and that Lrig proteins regulate degradation of many different transmembrane receptors (Hedman and Henriksson, 2007). Ntn1 is best known as an axon guidance molecule, which signals through the Ig superfamily of receptors DCC (Deleted in Colorectal Cancer) and Neogenin1, as well as the Unc5 family of receptors (Unc5Ha-d) (Moore et al., 2007). Outside of the nervous system, Ntn1 signals through Neogenin (Srinivasan et al., 2003), Unc5Hb (Lu et al., 2004), and Integrin α3/6 receptors (Yebra et al., 2003) to regulate cell adhesion, migration, and other aspects of tissue morphogenesis.

To identify relevant receptors, we asked whether any of the known Ntn1 receptors is required for inner ear morphogenesis. In situ hybridization screens by our lab and others revealed Unc5hb, Neogenin, and Integrin α 3/6 as potential candidates (Matilainen et al., 2007). However, although Unc5hb is expressed together with Lrig3 in non-fusing epithelium, the inner ear forms normally in Unc5hb mutant mice (Supp. Fig. 5). Moreover, none of the known Ntn1 receptors that are expressed in the developing otic epithelium (Neogenin, Integrin α3/6) or surrounding mesenchyme (Unc5hc) are required for canal morphogenesis (Supp. Fig. 5) (Matilainen et al., 2007).

Interestingly, the pro-angiogenic activities of Ntn1 have been proposed to be independent of known receptors, suggesting an alternative binding partner in this system (Wilson et al., 2006). Although Lrig3 is a cell surface protein, Lrig3 does not appear to be the missing receptor, as tagged versions of Lrig3 and Ntn1 do not co-localize in cultured cell lines (Supp. Fig. 6). Moreover, equal amounts of Ntn1 are secreted from cells in the presence and absence of Lrig3 (Supp. Fig. 6). Thus, Ntn1 appears to act through a non-canonical pathway in the inner ear to control basal lamina integrity, either via a novel receptor or a receptor-independent mechanism.

Lrig3 and Ntn1 participate in cross-repressive interactions that determine the timing and location of fusion

Since Lrig3 does not appear to act through the Ntn1 pathway, we considered alternative explanations for why basement membrane breakdown is expanded in Lrig3 mutants. Based on their complementary expression patterns and opposing activities, a simple idea is that the main function of Lrig3 is to restrict expression of Ntn1 to the fusion plate. As hypothesized, we found that Ntn1 expression is expanded to encompass the entire lateral pouch epithelium in Lrig3 mutants (Fig. 5A,E). Since Lrig3 appears to regulate Ntn1 expression at the transcriptional level, we asked whether the transcriptional downregulation of Lrig3 in the wild-type fusion plate (Fig. 3) is similarly a result of Ntn1 activity. To do this, we took advantage of the fact that a placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) reporter gene is present in the gene trap vector used to generate Lrig3 (Fig. 2A) but not in Ntn1 gene trap mutants (Serafini et al., 1996). As seen by β-galactosidase histochemistry (Fig. 3I), PLAP expression is reduced in the fusion plate in Lrig3 heterozygous embryos (Fig. 5B). In contrast, in Ntn1 mutants, PLAP expression persists throughout the lateral pouch (Fig. 5F). Surprisingly, we also observed sustained expression of Lrig3 itself in Lrig3 mutants, indicating that Lrig3 is required for its own downregulation (Fig. 5C,G). Therefore, we asked whether Ntn1 transcription is also autoregulated. Indeed, Ntn1-β geo expression is lost from the lateral pouch in Ntn1 mutants (Fig. 5D,H). Ntn1 autoregulation appears to be limited to the lateral pouch, since no changes in expression occur in the dorsal pouch. Together, these experiments show that mutually antagonistic interactions between Lrig3 and Ntn1 restrict Ntn1 expression to fusion plate cells and Lrig3 expression to non-fusing epithelium. This feedback loop seems to be uniquely important for lateral canal development, suggesting that new mechanisms operate in this most recently evolved semicircular canal.

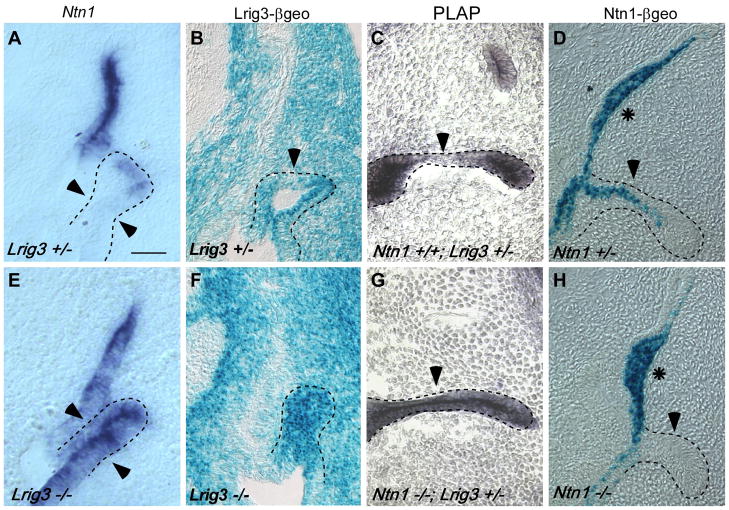

Fig. 5. Lrig3 and Ntn1 participate in cross-repressive interactions that define the fusing and non-fusing domains of the lateral pouch.

(A, E) In situ hybridization of Ntn1 on transverse sections through E12 Lrig3 +/− (A) and −/− (E) embryos. In Lrig3 mutants, Ntn1 expression is expanded to fill the lateral pouch (outlined). (B,F) Lrig3 and Ntn1 mutant mice were generated with two different gene trap vectors, so only Lrig3LST016 mice carry a Placental Alkaline Phosphatase (PLAP) reporter. Hence, PLAP histochemistry reveals Lrig3 transcription in Ntn1+/+;Lrig3+/− (B) and Ntn1−/−; Lrig3+/− embryos (F) at E12.5. Like β-geo, PLAP staining of Lrig3 heterozygotes (B) is absent from the fusion plate at E12.5 (arrowhead). In contrast, Lrig3 transcription is sustained in the fusion plate of age-matched Ntn1 homozygotes (F). Note that these embryos are 12 hours older than those in A, C, E, and G. (C, G) β-galactosidase histochemistry of E12 Lrig3 +/− (C) and Lrig3 −/− (G) littermates. As previously demonstrated (Fig. 3), Lrig3- βgeo levels are reduced in fusion plate cells (arrowhead, C) compared to the surrounding epithelium. However, in Lrig3 mutants (G) reporter activity is present at high levels throughout the pouch. (D, H) β-galactosidase histochemistry of E12 Ntn1 +/− (D) and −/− (H) littermates. Ntn1-βgeo is active in the fusion plate (arrowhead) in heterozygotes (D), consistent with in situ hybridization results (see Fig. 3). However, no activity is detected in the lateral pouch of Ntn1 homozygotes (H). Ntn1-βgeo expression is unchanged in the dorsal pouch (asterisks). Scale bar: 50 μm.

Loss of one copy of Ntn1 is sufficient to rescue inner ear defects in Lrig3 mutants

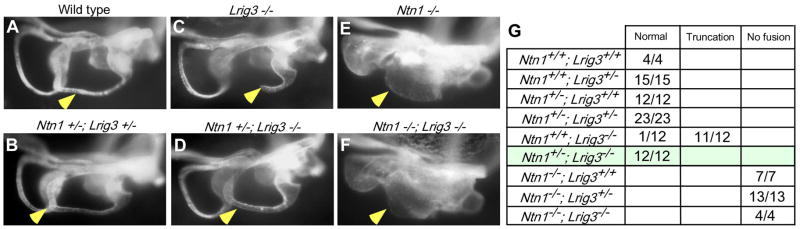

The presence of cross-repressive interactions between Lrig3 and Ntn1 suggests that a slight reduction in Ntn1 levels might be sufficient to compensate for the loss of Lrig3. To test this idea, we reduced the dosage of Ntn1 in Lrig3 mutant mice by intercrossing Ntn1+−-; Lrig3+/− transheterozygotes and collecting E14.5 embryos (n=81) for paintfilling (Fig. 6). Wild-type (n=4/4) and transheterozygous (n=23/23) embryos developed normal canals (Fig. 6A,B,G), while littermates homozygous for Lrig3 but wild type for Ntn1 exhibited lateral canal truncations, as expected (n=11/12 ears) (Fig. 6C,G). In contrast, no truncations occurred in Lrig3 homozygotes that were also heterozygous for Ntn1 (n=12/12 ears) (Fig. 6D,G), indicating that the Lrig3 phenotype is caused by a failure to properly regulate Ntn1 levels in fusion plate cells. Consistent with the complete rescue, adult Lrig3−/−;Ntn1+/− mice did not display circling behavior (n=16). Since the size and shape of the canal pouch is similar in Ntn1 (Fig. 6E,G) (n=7) and Ntn1;Lrig3 double mutant embryos (Fig. 6F,G) (n=4), Lrig3 likely acts upstream of Ntn1.

Fig. 6. The Lrig3 mutant lateral canal truncation is rescued by removal of one copy of Ntn1.

(A–F) Paintfilled E14 inner ears from transheterozygous intercross littermates. Canals (arrowheads) are normal in wild-type (A) and transheterozygous (B) embryos, while the lateral canal is truncated in Lrig3 homozygotes (C). The truncation is fully rescued when one wild type copy of Ntn1 is removed from Lrig3 homozygotes (D). Fusion does not occur in Ntn1 mutants (E) or Ntn1;Lrig3 double mutants (F). (G) Table summarizing the proportion of ears with normal, truncated, or unfused semicircular canals for each genotype in offspring from Ntn1+/−; Lrig3+/− intercrosses. The rescued population is highlighted in green. Note that the Ntn1 phenotype is not influenced by the absence of Lrig3.

We conclude that Lrig3 plays a pivotal role in lateral canal morphogenesis by restricting Ntn1 expression to the fusion plate. Cross-repressive interactions between Lrig3 and Ntn1 coordinate the timing and location of fusion, thereby determining the shape of the lateral canal.

DISCUSSION

A central challenge in developmental biology is understanding how signaling pathways cooperate to sculpt tissues with complex three-dimensional shapes. Here, we describe the presence of a novel feedback loop that restricts the expression of two genes with opposing functions to discrete domains of the otic vesicle during inner ear morphogenesis. Because the pattern of Ntn1 expression determines when and where fusion occurs, the spatiotemporal regulation of Ntn1 through cross-repressive interactions with Lrig3 ensures perfect morphogenesis of the elaborate structure of the inner ear.

Historically, much emphasis has been placed on the identification of determinants that define domains within the anlage of a developing structure. More recently, however, it has become clear that an additional level of control is needed to restrict the spatiotemporal activities of each factor. A common solution to this problem is the production of a feedback-induced antagonist that dampens the activity of a signaling pathway after activation, as is the case for Sprouty and Sef proteins in the FGF pathway (Shim et al., 2005; Tsang and Dawid, 2004). Signaling activity is also modulated by the basal lamina, which can limit dispersal of the protein and its ability to bind to its receptor (Relan and Schuger, 1999). The Lrig3/Ntn1 feedback loop incorporates both of these features: the induction of an antagonist, Lrig3, which controls the timing and extent of Ntn1-dependent basal lamina breakdown.

The Ntn1/Lrig3 feedback loop uncovered by this analysis is a novel mechanism for modulating expression of Ntn1 during development. In addition to the developing canals, Lrig3 and Ntn1 are also expressed in many other regions of the embryo, including the cochlea, neural tube, and somites (Supp. Fig. 1). Although no alterations of these tissues are obvious in Lrig3 mutant mice (data not shown), this may be due to compensation by the close family member Lrig1. Indeed, our expression studies indicate that the only two places where Lrig1 and Lrig3 do not overlap are the lateral canal pouch and the branchial arches, consistent with the lateral canal truncation and craniofacial abnormalities evident in Lrig3 mutant mice. Conversely, psoriasis is the only salient defect reported in Lrig1 mutant mice (Suzuki et al., 2002). Hence, Lrig1; Lrig3 double mutants may exhibit additional phenotypes related to misregulation of Ntn1 and may reveal a general mechanism for Ntn1 regulation.

Abnormal regulation of Ntn1 by Lrig may have broad implications in disease since disruption of the laminin network is a major factor in tumor invasion (Gupta and Massague, 2006). Consistent with this idea, all three Lrig genes are downregulated in certain human cancers, with Lrig1 studied most extensively (Guo et al., 2006; Hedman and Henriksson, 2007; Hedman et al., 2002; Lindstrom et al., 2007; Ljuslinder et al., 2007). Strikingly, the loss of Lrig1 correlates with worse outcomes in advanced stage cervical cancer (Lindstrom et al., 2007) and squamous cell carcinomas (Tanemura et al., 2005). In addition, the presence of Lrig1 is sufficient to inhibit the invasive behavior of bladder cancer cell lines and to prevent breakdown of fibronectin in a cell-matrix adhesion assay (Yang et al., 2006). Conversely, increased Ntn-1 induces tumor growth and invasion in human colorectal cell lines (Rodrigues et al., 2007) and is associated with poor prognoses for adenocarcinoma (Link et al., 2007). While the effect of Ntn-1 on tumor behavior is mediated in part by inhibition of apoptosis through the DCC and Unc5h dependence receptors (Fitamant et al., 2008; Mazelin et al., 2004; Rodrigues et al., 2007), our data raise the possibility that in some tumors, Ntn-1 may act downstream of Lrig3 to facilitate basement membrane breakdown and tumor metastasis.

Based on the current understanding of this poorly characterized family of proteins, it is likely that Lrig3 represses Ntn1 transcription by regulating activity of a receptor tyrosine kinase signaling pathway. The best studied family member, Lrig1, is induced by EGF signaling and antagonizes downstream signaling events by causing degradation of all four ErbB receptors (Gur et al., 2004; Laederich et al., 2004). Lrig1 has also been implicated as a negative regulator of Met and Ret receptor tyrosine kinases (rTK) (Ledda et al., 2008; Shattuck et al., 2007), raising the possibility that Lrigs serve as general antagonists of rTKs. Consistent with this idea, Lrig3 can bind to the FGF receptor tyrosine kinase receptor in vitro and inhibits FGF signaling in the developing neural crest in Xenopus (Zhao et al., 2008). This function may be conserved in mice, since Lrig3 morphant tadpoles exhibit craniofacial defects similar to what is observed in Lrig3 mutant mice. Since FGF signaling plays a prominent role in canal morphogenesis (Chang et al., 2004; Pauley et al., 2003; Pirvola et al., 2004), the Lrig3 inner ear phenotype is also likely to be caused by aberrant FGF activity. However, although FGF ligands and receptors have been implicated, the downstream signaling events in the fusion plate remain elusive, with no known target genes and multiple feedback-induced antagonists that are not required for canal development (Abraira et al., 2007; Shim et al., 2005). Hence, until we have a better understanding of how FGF signaling acts specifically in the fusion plate, it will be difficult to determine whether and how Lrig3 influences FGF activity.

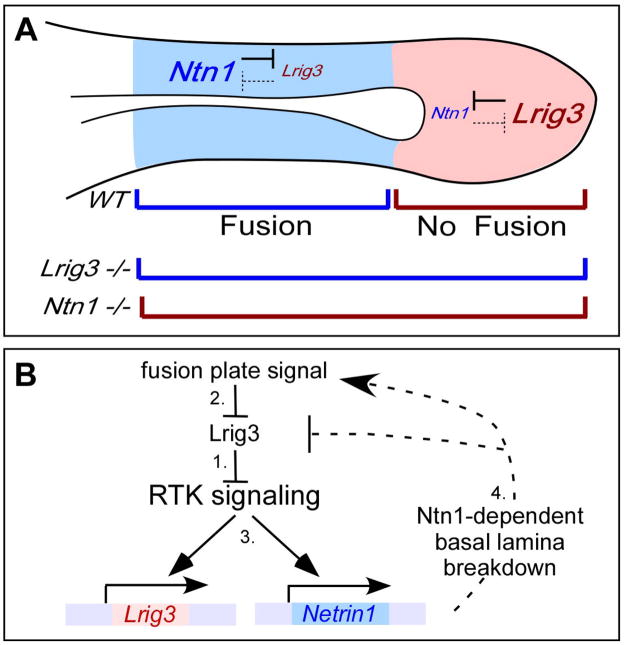

Together with what is known about Lrig functions, the simplest interpretation of our results is that Lrig3 titrates activity of a receptor tyrosine kinase signaling pathway that normally induces expression of Ntn1, as well as Lrig3 itself (Fig. 7). Prior to fusion, Lrig3 is expressed throughout the lateral pouch, where it inhibits RTK activity and prevents fusion from beginning (Step 1, Fig. 7). Subsequently, we hypothesize the presence of a fusion plate inducing signal, which overcomes Lrig3-mediated inhibition (Step 2, Fig. 7) to activate the RTK pathway and allow expression of Ntn1 (Step 3, Fig. 7). Ntn1, in turn, enhances activity of this same pathway, most likely by promoting breakdown of the basal lamina (Step 4, Fig. 7). Hence, in Lrig3 mutants, increased RTK signaling results in early and expanded Ntn1 expression, as well as persistent Lrig3 expression (Fig. 7A). Conversely, in Ntn1 mutants, RTK signaling occurs at low levels, both because of the presence of Lrig3 and the failure to potentiate the pathway through Ntn1-mediated breakdown of the basal lamina. Due to the low level of RTK signaling, canal development arrests at the canal pouch stage, such that expression of Ntn1 is lost and Lrig3 is never reduced (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7. Proposed model for the Lrig3/Ntn1 feedback loop.

(A) A diagrammatic view of the lateral pouch during canal morphogenesis. Cross-repressive interactions between Lrig3 and Ntn1 define the boundary between fusing (blue) and non-fusing (red) regions of the otic epithelium. When the regulatory loop is interrupted by loss of Lrig3, fusion is expanded, while in Ntn1 mutants, fusion does not occur. Interactions between Lrig3 and Ntn1 ensure that these two genes become confined to distinct domains of the lateral pouch. (B) We propose the following model for the Lrig3/Ntn1 feedback loop. Lrig3 is present throughout the canal pouch before fusion and inhibits activity of a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling pathway (1). Subsequently, fusion is initiated by an unknown fusion plate signal, which we hypothesize acts through the RTK pathway by inhibiting Lrig3 (2), resulting in transcription of Ntn1 (3). Lrig3 initially continues to be transcribed, as expected for a feedback-induced antagonist. However, the increased levels of Ntn1 eventually inhibit Lrig3 expression, either by inhibiting Lrig3 or by potentiating activity of the fusion plate signal. For instance, Ntn1 protein may augment activity of the RTK pathway by promoting basal lamina breakdown (4).

A key feature of this model is the fact that Lrig3 is present prior to any of these events, but is also critical for the subsequent emergence of mutually exclusive domains of Lrig3 and Ntn1 expression. Since Lrig3 activity is required for the feedback loop to function properly, the initial Lrig3 expression also fails to be downregulated in Lrig3 mutants. Hence, the subsequent interactions between Lrig3 and Ntn1 serve to simultaneously reduce Lrig3 transcription and increase Ntn1 only in the regions that receive the inducing signal.

The proposed model fits both with the results reported here as well as the known activities of Lrig3 and Ntn1, but also raises several questions for future consideration. Unfortunately, the ability of Lrig proteins to bind to widely divergent members of the receptor tyrosine kinase family in vitro will make it difficult to pinpoint a single binding partner in vivo, especially in a structure as small as the lateral pouch. The best candidate is the FGF receptor, not only because Lrig3 is known to bind to and inhibit FGF receptor, but also because of the known importance of FGF signaling during inner ear development. In the developing vestibular system, FGF signaling cooperates with the BMP pathway to define sensory and non-sensory domains of the inner ear (Chang et al., 2004; Pauley et al., 2003) and is subsequently required for proliferation of the periotic mesenchyme (Pirvola et al., 2004). Moreover, mesenchymal proliferation is reduced in Ntn1 mutants, consistent with the idea that Ntn1-dependent breakdown of the basal lamina promotes the ability of the FGF ligand to act during canal morphogenesis. Indeed, it is well established that FGF signaling levels are modified by interactions with the basement membrane during other types of tissue morphogenesis (Lonai, 2003; Patel et al., 2007). Although it remains unclear how Ntn1 mediates its effects, the extent of basement membrane breakdown correlates strongly with the amount of Ntn1: breakdown does not occur in Ntn1 mutants, is expanded in the presence of ectopic Ntn1 in Lrig3 mutants, and proceeds normally in rescued embryos that have only one copy of Ntn1. Additional experiments will be needed to understand the specific function of Ntn1 in the basement membrane, as well as how Ntn1-induced changes influence the activity of FGF or other signaling ligands in the extracellular matrix.

Because modest perturbations in the structure of the inner ear cause severe behavioral deficits, our genetic studies were able to reveal the consequences of slight changes in signaling activity that may be undetectable by in vitro methods. Indeed, lateral canal truncations also occur in BMP4 heterozygotes, emphasizing the unusual sensitivity of the developing inner ear to modest changes in signaling levels (Chang et al., 2008). Similarly, in humans, the lateral canal is the most common site of inner ear anomalies (Sando et al., 2001; Sando et al., 1984), emphasizing the importance of identifying the molecular players that make this canal unusually susceptible to developmental insults. Hence, the Lrig3/Ntn1 feedback loop may provide an additional safeguard for tissues whose function depends critically on the perfect morphogenesis of complex structures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank X. Lu for providing Unc5hb mutant tissue, D. Goodenough for insights into the EM results, N. Hyun and N. Pogue for genotyping assistance, and R. Segal, X. Lu, M. Scott and members of the Goodrich laboratory for advice on the project and comments on the manuscript. We are also grateful to S. Walker and J. Brugge for assistance with the acinar cultures. This work was supported by grants R01 DC7195 (L.V.G.) and F31 DC008450 (V.E.A.) from the N.I.H./N.I.D.C.D., and funding from the C.I.H.R. (J.S.), the Smith Family New Investigators Program (L.V.G.), and the Mathers Charitable Foundation (L.V.G.).

References

- Abraira VE, Hyun N, Tucker AF, Coling DE, Brown MC, Lu C, Hoffman GR, Goodrich LV. Changes in Sef levels influence auditory brainstem development and function. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4273–82. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3477-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W, Brigande JV, Fekete DM, Wu DK. The development of semicircular canals in the inner ear: role of FGFs in sensory cristae. Development. 2004;131:4201–11. doi: 10.1242/dev.01292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W, Lin Z, Kulessa H, Hebert J, Hogan BL, Wu DK. Bmp4 is essential for the formation of the vestibular apparatus that detects angular head movements. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete DM. Development of the vertebrate ear: insights from knockouts and mutants. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:263–9. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01366-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete DM, Wu DK. Revisiting cell fate specification in the inner ear. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitamant J, Guenebeaud C, Coissieux MM, Guix C, Treilleux I, Scoazec JY, Bachelot T, Bernet A, Mehlen P. Netrin-1 expression confers a selective advantage for tumor cell survival in metastatic breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4850–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709810105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, Holmlund C, Henriksson R, Hedman H. The LRIG gene family has three vertebrate paralogs widely expressed in human and mouse tissues and a homolog in Ascidiacea. Genomics. 2004;84:157–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, Nilsson J, Haapasalo H, Raheem O, Bergenheim T, Hedman H, Henriksson R. Perinuclear leucine-rich repeats and immunoglobulin-like domain proteins (LRIG1–3) as prognostic indicators in astrocytic tumors. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2006;111:238–46. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta GP, Massague J. Cancer metastasis: building a framework. Cell. 2006;127:679–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur G, Rubin C, Katz M, Amit I, Citri A, Nilsson J, Amariglio N, Henriksson R, Rechavi G, Hedman H, et al. LRIG1 restricts growth factor signaling by enhancing receptor ubiquitylation and degradation. Embo J. 2004;23:3270–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedman H, Henriksson R. LRIG inhibitors of growth factor signalling - double-edged swords in human cancer? Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:676–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedman H, Nilsson J, Guo D, Henriksson R. Is LRIG1 a tumour suppressor gene at chromosome 3p14.3? Acta Oncol. 2002;41:352–4. doi: 10.1080/028418602760169398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy TE. Cellular mechanisms of netrin function: long-range and short-range actions. Biochem Cell Biol. 2000;78:569–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laederich MB, Funes-Duran M, Yen L, Ingalla E, Wu X, Carraway KL, 3rd, Sweeney C. The leucine-rich repeat protein LRIG1 is a negative regulator of ErbB family receptor tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47050–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledda F, Bieraugel O, Fard SS, Vilar M, Paratcha G. Lrig1 is an endogenous inhibitor of Ret receptor tyrosine kinase activation, downstream signaling, and biological responses to GDNF. J Neurosci. 2008;28:39–49. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2196-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton PA, Mitchell KJ, Goodrich LV, Lu X, Pinson K, Scherz P, Skarnes WC, Tessier-Lavigne M. Defining brain wiring patterns and mechanisms through gene trapping in mice. Nature. 2001;410:174–9. doi: 10.1038/35065539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom AK, Ekman K, Stendahl U, Tot T, Henriksson R, Hedman H, Hellberg D. LRIG1 and squamous epithelial uterine cervical cancer: correlation to prognosis, other tumor markers, sex steroid hormones, and smoking. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007 doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BC, Reichelt U, Schreiber M, Kaifi JT, Wachowiak R, Bogoevski D, Bubenheim M, Cataldegirmen G, Gawad KA, Issa R, et al. Prognostic implications of netrin-1 expression and its receptors in patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2591–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9469-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljuslinder I, Golovleva I, Palmqvist R, Oberg A, Stenling R, Jonsson Y, Hedman H, Henriksson R, Malmer B. LRIG1 expression in colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2007:1–5. doi: 10.1080/02841860701426823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonai P. Epithelial mesenchymal interactions, the ECM and limb development. J Anat. 2003;202:43–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2003.00143.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Le Noble F, Yuan L, Jiang Q, De Lafarge B, Sugiyama D, Breant C, Claes F, De Smet F, Thomas JL, et al. The netrin receptor UNC5B mediates guidance events controlling morphogenesis of the vascular system. Nature. 2004;432:179–86. doi: 10.1038/nature03080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P, Swanson GJ. Descriptive and experimental analysis of the epithelial remodellings that control semicircular canal formation in the developing mouse inner ear. Dev Biol. 1993;159:549–58. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matilainen T, Haugas M, Kreidberg JA, Salminen M. Analysis of Netrin 1 receptors during inner ear development. Int J Dev Biol. 2007;51:409–13. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072273tm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazelin L, Bernet A, Bonod-Bidaud C, Pays L, Arnaud S, Gespach C, Bredesen DE, Scoazec JY, Mehlen P. Netrin-1 controls colorectal tumorigenesis by regulating apoptosis. Nature. 2004;431:80–4. doi: 10.1038/nature02788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlo G, Laura P, Mantero S, Zerega B, Adamska M, Rinkwitz S, Bober E, Levi G. The Dlx5 homeobox gene is essential for vestibular morphogenesis in the mouse embryo through a BMP4-mediated pathway. Dev Biol. 2002;248:157–169. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KJ, Pinson KI, Kelly OG, Brennan J, Zupicich J, Scherz P, Leighton PA, Goodrich LV, Lu X, Avery BJ, et al. Functional analysis of secreted and transmembrane proteins critical to mouse development. Nat Genet. 2001;28:241–9. doi: 10.1038/90074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SW, Tessier-Lavigne M, Kennedy TE. Netrins and their receptors. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;621:17–31. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-76715-4_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morsli H, Tuorto F, Choo D, Postiglione MP, Simeone A, Wu DK. Otx1 and Otx2 activities are required for the normal development of the mouse inner ear. Development. 1999;126:2335–43. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel VN, Knox SM, Likar KM, Lathrop CA, Hossain R, Eftekhari S, Whitelock JM, Elkin M, Vlodavsky I, Hoffman MP. Heparanase cleavage of perlecan heparan sulfate modulates FGF10 activity during ex vivo submandibular gland branching morphogenesis. Development. 2007;134:4177–86. doi: 10.1242/dev.011171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauley S, Wright TJ, Pirvola U, Ornitz D, Beisel K, Fritzsch B. Expression and function of FGF10 in mammalian inner ear development. Dev Dyn. 2003;227:203–15. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirvola U, Zhang X, Mantela J, Ornitz DM, Ylikoski J. Fgf9 signaling regulates inner ear morphogenesis through epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. Dev Biol. 2004;273:350–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relan NK, Schuger L. Basement membranes in development. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 1999;2:103–18. doi: 10.1007/s100249900098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues S, De Wever O, Bruyneel E, Rooney RJ, Gespach C. Opposing roles of netrin-1 and the dependence receptor DCC in cancer cell invasion, tumor growth and metastasis. Oncogene. 2007;26:5615–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen M, Meyer BI, Bober E, Gruss P. Netrin 1 is required for semicircular canal formation in the mouse inner ear. Development. 2000;127:13–22. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sando I, Orita Y, Miura M, Balaban C. Vestibular abnormalities in congenital disorders. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2001;942:15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sando I, Takahara T, Ogawa A. Congenital Anomalies of the Inner Ear. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1984;112:110–118. doi: 10.1177/00034894840930s419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiders FI, Maertens B, Bose K, Li Y, Brunken WJ, Paulsson M, Smyth N, Koch M. Binding of netrin-4 to laminin short arms regulates basement membrane assembly. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23750–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk F, Baron U, Rajewsky K. A cre-transgenic mouse strain for the ubiquitous deletion of loxP-flanked gene segments including deletion in germ cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:5080–1. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.24.5080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini T, Colamarino SA, Leonardo ED, Wang H, Beddington R, Skarnes WC, Tessier-Lavigne M. Netrin-1 is required for commissural axon guidance in the developing vertebrate nervous system. Cell. 1996;87:1001–14. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81795-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck DL, Miller JK, Laederich M, Funes M, Petersen H, Carraway KL, 3rd, Sweeney C. LRIG1 is a novel negative regulator of the Met receptor and opposes Met and Her2 synergy. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1934–46. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00757-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim K, Minowada G, Coling DE, Martin GR. Sprouty2, a mouse deafness gene, regulates cell fate decisions in the auditory sensory epithelium by antagonizing FGF signaling. Dev Cell. 2005;8:553–64. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan K, Strickland P, Valdes A, Shin GC, Hinck L. Netrin-1/neogenin interaction stabilizes multipotent progenitor cap cells during mammary gland morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2003;4:371–82. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streeter G. On the development of the membranous labyrinth and the acoustic and facial nerves in the human embryo. Am J Anat. 1907;6:139–165. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Miura H, Tanemura A, Kobayashi K, Kondoh G, Sano S, Ozawa K, Inui S, Nakata A, Takagi T, et al. Targeted disruption of LIG-1 gene results in psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia. FEBS Lett. 2002;521:67–71. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02824-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanemura A, Nagasawa T, Inui S, Itami S. LRIG-1 provides a novel prognostic predictor in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: immunohistochemical analysis for 38 cases. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:423–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang M, Dawid IB. Promotion and attenuation of FGF signaling through the Ras-MAPK pathway. Sci STKE. 2004;2004:pe17. doi: 10.1126/stke.2282004pe17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Van De Water T, TL Inner ear and maternal reproductive defects in mice lacking the Hmx3 homeobox gene. Development. 1998;125:621–634. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.4.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BD, Ii M, Park KW, Suli A, Sorensen LK, Larrieu-Lahargue F, Urness LD, Suh W, Asai J, Kock GA, et al. Netrins promote developmental and therapeutic angiogenesis. Science. 2006;313:640–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1124704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang WM, Yan ZJ, Ye ZQ, Guo DS. LRIG1, a candidate tumour-suppressor gene in human bladder cancer cell line BIU87. BJU Int. 2006;98:898–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yebra M, Montgomery AM, Diaferia GR, Kaido T, Silletti S, Perez B, Just ML, Hildbrand S, Hurford R, Florkiewicz E, et al. Recognition of the neural chemoattractant Netrin-1 by integrins alpha6beta4 and alpha3beta1 regulates epithelial cell adhesion and migration. Dev Cell. 2003;5:695–707. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Tanegashima K, Ro H, Dawid IB. Lrig3 regulates neural crest formation in Xenopus by modulating Fgf and Wnt signaling pathways. Development. 2008;135:1283–93. doi: 10.1242/dev.015073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.