Abstract

Background

The underuse of effective contraceptive methods by women at risk for unintended pregnancy is a major factor contributing to the high rate of unintended pregnancy in the United States. As health care providers are important contributors to women’s contraceptive use, this study was conducted to assess provider knowledge about contraception.

Study Design

Bivariate and multivariate analyses were performed using data collected from a convenience sample of health care providers (physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants) at meetings of the professional societies of family medicine and obstetrics and gynecology.

Results

Younger providers were more knowledgeable, as were obstetrician/gynecologists, female providers and providers who provide intrauterine contraception in their practice.

Conclusions

The lack of consistent and accurate knowledge about contraception among providers has the potential to dramatically affect providers’ ability to provide quality contraceptive care for their patients, which would have an impact on their ability to prevent unintended pregnancies.

Keywords: Contraceptioon, Provider knowledge, Contraceptive counseling, Unintended pregnancy

1. Introduction

The underuse of effective contraceptive methods by women at risk for unintended pregnancy is a major factor contributing to the high rate of unintended pregnancy in the United States, with over 10% of women at risk for unintended pregnancy not using any form of contraception, and many more relying on low-efficacy methods such as barrier or fertility awareness methods [1]. In addition, very few women of reproductive age in the United States (approximately 2%) use long-acting, reversible contraception such as intrauterine contraception (IUC), compared to the more than 20% of reproductive age women using these methods in European countries [2].

Several factors contribute to the underuse of contraceptive methods by women in the United States, including patient preferences and health system factors such as inadequate health insurance coverage of contraceptives [3, 4]. An additional contributing factor is the information that women receive from their providers about contraceptive methods. While the impact of contraceptive counseling on use of contraception is not well understood [5], several studies have linked quality of care, including the quality of information provided, to use of contraceptive methods [6–8]. Further, a study of patients presenting for termination of pregnancy found a direct effect of counseling on unintended pregnancy. In this study 14% of women requesting an abortion had experienced a communication failure or received misinformation from their provider about contraception that resulted in the use of a less effective method of contraception or the incorrect use of a contraceptive method [9].

One contributor to poor communication between providers and patients about contraceptive methods may be that providers have incomplete knowledge of evidence-based information about contraceptive methods. This is particularly relevant currently, as there has been a rapid expansion of contraceptive technology in the past decade [10]. Several studies have suggested that provider knowledge is in fact deficient in some aspects of contraception. For example, in a recent study about provider knowledge about IUC, just under half the providers were not aware of the evidence-based guidelines for eligibility for IUC [11], including a commonly held, yet incorrect, belief that nulliparous women and women with a history of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) were not appropriate candidates for this method [12]. A similar finding was identified in a Canadian study of family physicians, which found that 60% of family physicians thought PID and ectopic pregnancy were major risks of IUC [13]. Another study assessed the contraceptive knowledge of family medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatric and internal medicine residents on a variety of topics and found that, overall, residents answered just over 50% of these questions correctly. Being an obstetrician-gynecologist, being female, and inserting IUC were associated with higher levels of knowledge [14].

While these previous studies suggest that provider knowledge about contraception may be limited, they have primarily focused on IUC, have utilized small samples from limited geographic areas, and have only investigated provider demographics among doctors in training. Our study expands on this previous literature by investigating providers’ knowledge about a variety of contraceptive methods, utilizing a national sample, and determining which provider characteristics were associated with higher knowledge among practicing providers.

1. Materials and methods

1.1. Study design

A convenience sample of health care providers [physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs)] was recruited in the exhibit halls of meetings of the professional societies of family medicine and obstetrics and gynecology to complete a computerized survey. Each health care provider was asked to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement on a five-point scale (strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat agree, and strongly agree) with seven statements about the eligibility for and use of specific contraceptive methods as part of a larger study about contraceptive prescribing. Demographics of the providers were also collected, including gender, age, self-identified race/ethnicity, and practice type.

The seven statements about eligibility for and use of contraception were selected to cover a range of contraceptive topics. For six of the seven statements there is general consensus in the medical literature about the validity of the statement. We also selected one statement, regarding whether there is an increased risk of venous thrombosis in users of the contraceptive patch, about which there is currently a lack of consensus in the literature in order to gain information about this controversial area. The statements are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Statements assessing providers’ contraceptive knowledge

| Statement | Correct answer |

|---|---|

| There is an increased risk of infertility associated with the use of intrauterine contraception. |

Strongly disagree [15] |

| A woman who uses intrauterine contraception has a higher risk of pelvic inflammatory disease than if she were not to use intrauterine contraception. |

Strongly disagree [16] (Note: While the risk of PID is believed to be increased in the first 20 days after insertion, we presumed that this question would be interpreted as applying to a generally increased risk, not a risk only at the time of insertion.) |

| Emergency contraception (Plan B) is only effective up to 48 hours after intercourse. |

Strongly disagree [17] |

| Women with migraine with aura should not be prescribed combined hormonal contraceptives. |

Strongly agree [12, 18, 19] |

| Women with a history of deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism should not be prescribed progestin-only contraceptives. |

Disagree [12, 20] |

| Hypertension, even if well controlled, is an absolute contraindication to combined hormonal contraception. |

Disagree [12] |

| There is an increased risk of deep venous thrombosis with use of the contraceptive patch (Ortho Evra) as compared to combined hormonal contraceptive pills with 20–35 mcg of estrogen. |

Controversial [21–23] (Note: The FDA released a black box warning regarding increased levels of estrogen with the contraceptive patch in 2006 compared to oral contraceptive pills. However,the epidemiologic studies investigating whether these increased levels result in higher rates of DVT have yielded inconsistent results.) |

We performed bivariate analyses using chi-squared, Student’s t-, and Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. For our multivariable models, we dichotomized the 5-point scale, so that for the questions for which “Strongly Agree” was wrong, a response of either “Somewhat Agree” or “Strongly Agree” was coded as incorrect. For the question regarding the use of combined hormonal contraceptives in women with migraine, an answer of either “Somewhat Disagree” or “Strongly Disagree” was coded as incorrect. All demographic variables were entered into multivariate logistic regression models for each question. In order to minimize the possibility of confounding, we retained all variables with a p value of <0.10 in any model. All analyses were performed using STATA 9.2 (College Station, TX).

The University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research approved this study.

2. Results

Five hundred twenty-four health care providers completed the computerized survey between September 2007 and May 2008 at two regional meetings and one national meeting of the American College of Obstetrician Gynecologists, and one national meeting of the American Academy of Family Physicians. The demographics of these providers are shown in Table 2. The sample consisted of mostly MD/DOs (96%), and was well distributed by gender and between the specialties of obstetrics/gynecology and family medicine. The majority of subjects provided a substantial amount of contraceptive care, including more than 70% who inserted IUC in their practice. The subjects included health care providers from all four regions of the United States.

Table 2.

Study participant characteristics (n=524)

| All subjects | |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 45.9 (10.5) |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |

| White | 76.9 |

| Black | 7.8 |

| Latina | 3.8 |

| Asian | 9.2 |

| Other | 2.3 |

| Male sex (%) | 53.6 |

| Professional degree (%) | |

| MD/DO | 96.0 |

| NP/PA | 4.0 |

| Specialty (%) | |

| Ob/Gyn | 59.0 |

| Family medicine | 38.7 |

| Other | 2.3 |

| Board certified (%) | 92.0 |

| Performs IUC insertions (%) | 74.1 |

| Frequency of prescribing contraception (%) | |

| Never or rarely | 5.9 |

| Occasionally | 16.2 |

| Frequently | 77.9 |

| Accepts Medicaid (%) | 81.3 |

| Hours/week of clinical work (%) | |

| <10 | 5.0 |

| 10–20 | 7.4 |

| 21–30 | 14.7 |

| >30 | 72.9 |

| Practice type (%) | |

| Academic | 24.6 |

| Private | 54.4 |

| Family planning or public health clinic | 13.7 |

| HMO | 7.3 |

| Region (%) | |

| Midwest | 31.7 |

| South | 30.2 |

| West | 19.5 |

| Northeast | 18.7 |

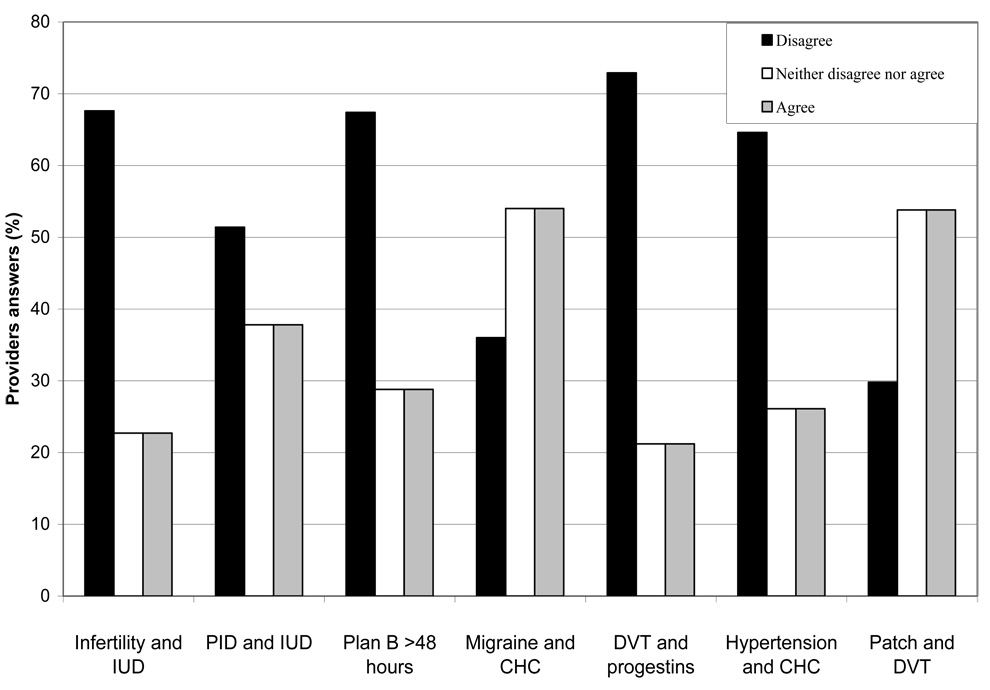

Providers’ responses to statements assessing knowledge of various contraceptive methods are shown in Fig. 1. Overall, 23% of providers answered incorrectly about the risk of infertility with IUC, 38% about the risk of PID with IUC, 29% about the appropriate timeframe for use of Plan B, 36% about the use of combined hormonal contraception in women with migraine with aura, 26% about the use of combined hormonal contraception in women with well-controlled hypertension, and 21% regarding whether it was acceptable to use progestin-only contraception in women with a history of venous thrombosis. With respect to whether the contraceptive patch is associated with increased risk of venous thrombosis, 54% agreed with the statement that an increased risk existed, whereas the remainder either disagreed or did not have an opinion.

Fig. 1.

Health care providers' knowledge about contraception (n=524).

Table 3 presents the association of provider characteristics with agreement with the statements assessing contraceptive knowledge. Younger providers were more knowledgeable in several areas, as were female providers, providers who provide contraceptive care frequently, obstetrician gynecologists, and providers who provide IUC in their practice. Providers practicing in an academic setting were less likely to believe that IUC use is associated with PID and that emergency contraception is only effective up to 48 h. Obstetrician/gynecologists, MD/DOs, those who provide more contraceptive care, and those who insert IUCs were more likely to believe that users of the contraceptive patch have an elevated risk of deep venous thrombosis. The number of hours spent performing clinical care and whether or not they were Board Certified were not associated with providers’ opinion about any of the statements.

Table 3.

Percent agreeing with each statement, by provider characteristics

| IUC and infertility |

IUC and PID |

Emergency Contracep- tion >48 hours |

Migraine* and CHC |

DVT and progestins |

Hyper- Tension and CHC |

Patch and DVT |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All providers | 22.7 | 37.8 | 28.8 | 36.1 | 21.2 | 26.1 | 53.8 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 26.0 | 41.6 | 34.9** | 35.6 | 25.3** | 30.6** | 53.0 |

| Female | 18.9 | 33.3 | 21.8** | 36.6 | 16.5** | 20.8** | 54.8 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 22.3 | 39.5 | 29.3 | 34.7 | 19.4** | 27.4 | 54.6 |

| Black | 24.4 | 31.7 | 22.0 | 31.7 | 36.6** | 26.5 | 61.0 |

| Latina | 10.0 | 40.0 | 20.0 | 55.0 | 35.0** | 26.3 | 40.0 |

| Asian | 25.0 | 31.3 | 37.5 | 39.6 | 16.7** | 16.3 | 47.9 |

| Other | 41.7 | 25.0 | 16.7 | 50.0 | 25.0** | 18.2 | 50.0 |

| Age, years | |||||||

| <36 | 15.2** | 23.9** | 14.1+ | 38.0 | 8.7+ | 18.8 | 62.0 |

| 36–45 | 19.1** | 34.3** | 25.8+ | 38.2 | 15.2+ | 24.4 | 55.6 |

| 46–55 | 25.9** | 46.3** | 34.6+ | 32.7 | 29.0+ | 29.6 | 45.7 |

| >55 | 31.5** | 43.5** | 39.1+ | 35.9 | 31.5+ | 30.3 | 56.5 |

| Specialty | |||||||

| Ob/Gyn | 12.0+ | 27.5+ | 16.5+ | 32.0** | 18.5 | 26.0 | 59.6** |

| Family medicine | 38.9+ | 54.2+ | 47.3+ | 42.9** | 25.6 | 25.6 | 46.3** |

| Other | 25.0+ | 25.0+ | 33.3+ | 25.0** | 16.7 | 36.4 | 33.3** |

|

Professional degree |

|||||||

| MD/DO | 22.9 | 37.6 | 28.6 | 36.4 | 21.1 | 25.6 | 54.9** |

| NP/PA | 19.1 | 42.9 | 33.3 | 28.6 | 23.8 | 36.8 | 28.6** |

|

Frequency of prescribing contraception |

|||||||

| Never or rarely |

29.0+ | 35.5+ | 38.7+ | 45.2 | 25.9 | 24.1 | 32.3** |

| Occasionally | 42.4+ | 61.2+ | 49.4+ | 34.1 | 25.9 | 24.7 | 43.5** |

| Frequently | 18.1+ | 33.1+ | 23.8+ | 35.8 | 19.9 | 26.5 | 57.6** |

|

Board certification |

|||||||

| Yes | 22.8 | 38.8 | 28.6 | 35.7 | 21.2 | 26.3 | 52.7 |

| No | 21.4 | 26.2 | 31.0 | 40.5 | 21.4 | 23.5 | 66.7 |

|

Accepts Medicaid |

|||||||

| Yes | 23.0 | 36.2 | 29.1 | 36.2 | 20.0 | 26.3 | 56.8** |

| No | 21.4 | 44.9 | 27.6 | 35.7 | 26.5 | 25.3 | 40.8** |

|

Hours/week of clinical work (%) |

|||||||

| <10 | 30.8 | 50.0 | 23.1 | 23.1 | 15.4 | 27.3 | 46.2 |

| 10–20 | 25.6 | 30.8 | 28.2 | 35.9 | 18.0 | 37.1 | 56.4 |

| 21–30 | 20.8 | 35.1 | 23.4 | 37.7 | 20.8 | 19.4 | 58.4 |

| >30 | 22.3 | 38.2 | 30.4 | 36.7 | 22.0 | 26.3 | 53.1 |

| Practice type | |||||||

| Academic | 17.8 | 22.5** | 19.4** | 29.5 | 15.5 | 28.1 | 62.0 |

| Private | 25.3 | 43.2** | 32.3** | 38.6 | 25.6 | 24.7 | 49.1 |

| HMO | 13.2 | 42.1** | 26.3** | 39.5 | 15.8 | 30.6 | 60.5 |

| Family planning clinic/ community health center |

26.4 | 41.7** | 33.3** | 36.1 | 16.7 | 25.4 | 54.2 |

| Region | |||||||

| Midwest | 25.9 | 44.0 | 32.5 | 34.9** | 25.3 | 22.9** | 56.6 |

| South | 22.2 | 32.9 | 28.5 | 39.9** | 20.3 | 21.7** | 48.1 |

| West | 14.7 | 36.3 | 24.5 | 43.1** | 19.6 | 23.6** | 50.0 |

| Northeast | 26.5 | 36.8 | 27.6 | 24.5** | 17.4 | 40.9** | 62.2 |

|

Performs IUC insertions |

|||||||

| Yes | 15.0+ | 30.7+ | 20.9+ | 34.5 | 17.8** | 24.5 | 58.0** |

| No | 44.9+ | 58.1+ | 51.5+ | 40.4 | 30.9** | 30.1 | 41.9** |

Response option reversed for this question.

p<0.05.

p<0.001.

Of the six statements for which there is a consensus in the literature, only the two statements regarding IUC and the statement regarding emergency contraception were significantly associated with more than two provider characteristics in multivariate logistic regression models. These findings are presented in Table 4. For these statements, findings from the multivariate analysis were similar to the bivariate findings, with older age and being a family physician associated with lower levels of contraceptive knowledge and performing IUC insertions and frequently providing contraceptive care, as compared to providing contraceptive care occasionally, being associated with higher levels of knowledge. The associations between being female and working in an academic medical center and higher levels of knowledge were no longer significant for these statements.

Table 4.

Predictors of providers’ knowledge and attitudes about contraception

| IUC and infertility | IUC and PID | Emergency Contraception >48 hours |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (ref<36)* | |||

| 36–45 | 1.5 (0.7–3.3) | 1.7 (0.9–3.4) | 3.2 (1.4–7.3)* |

| 46–55 | 1.9 (0.8–4.3) | 2.5 (1.3–5.1)* | 4.4 (1.9–10.1)* |

| >56 | 3.7 (1.5–9.1)* | 2.7 (1.3–5.8)* | 6.9 (2.8–17.0)+ |

|

Specialty of obstetrics and gynecology (ref=Family medicine) |

0.3 (0.1–0.5)+ | 0.5 (0.3–0.8)* | 0.3 (0.1–0.4)+ |

|

Frequency of prescribing contraception (ref=frequently) |

|||

| Never or rarely |

0.7 (0.3–1.9) | 0.5 (0.2–1.4) | 0.9 (0.4–2.3) |

| Occasionally | 1.7 (1.0–3.2) | 2.4 (1.4–4.2)* | 1.7 (1.0–3.1) |

|

Board certified (ref=no) |

0.6 (0.2–1.7) | 0.8 (0.3–1.8) | 0.2 (0.1–0.6)* |

| Accepts Medicaid patients (ref=no) | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) | 0.6 (0.3–0.9)* | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) |

|

Does IUC insertions* (ref=no) |

0.4 (0.2–0.7)* | 0.5 (0.3–0.9)* | 0.5 (0.3–0.9)* |

p<0.05.

p<0.001.

Other variables included in the model are sex, race/ethnicity, professional degree, practice type, and region.

In the multivariate models, having the opinion that controlled hypertension is a contraindication to combined hormonal methods was significantly more common in females than males and in those practicing in the Northeast compared to those practicing in the all other regions (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.1–3.0 and OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.5–5.1 compared to the Midwest). Believing that progestin-only contraceptives were contraindicated in those with a history of deep vein thrombosis was significantly more likely among African American than White providers (OR 3.8, 95% CI 1.7–8.2), and with those of increasing age compared to those less than 36 years old (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.0–6.4 for age 36–45, OR 5.5, 95% CI 2.1–14.3 for age 46–55, and OR 6.6, 95% CI 2.4–18.1 for age >55). There were no provider characteristics that were significantly associated with belief that migraine with aura is not a contraindication to combined hormonal contraception. Believing that use of the contraceptive patch is associated with an increased risk of venous thrombosis was significantly less likely in MD/DOs (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1–0.9), and significantly more likely among those who accept Medicaid patients (1.8, 95% CI 1.1–2.9).

Discussion

This is the first study of which we are aware to assess practicing providers’ knowledge of a broad range of contraceptive topics. Our findings suggest that there is a considerable amount of misinformation about contraception among providers, and that gaps in knowledge are more common among older providers and family medicine providers. Additionally, providers who perform IUC insertions had higher levels of knowledge about the IUC and about emergency contraception, even when controlling for the amount of contraceptive care that they provide. Our study also found a high level of disagreement among practicing providers about the risk of DVT among users of the contraceptive patch.

The lack of knowledge about contraception has the potential to dramatically affect providers’ ability to provide quality contraceptive care to their patients, which could have an impact on their ability to prevent unintended pregnancies. As an example, the 29% of providers who were unaware of the WHO recommendation to administer emergency contraception up to 120 h after intercourse [12] would be likely to inappropriately limit its use in their patients. Likewise, an inability to accurately inform patients about the lack of association between IUC use and both infertility and PID could obstruct many women from receiving a highly effective and easy-to-use form of birth control [24]. Knowledge of actual contraindications for specific contraceptive methods is also essential to quality contraceptive care. As a result of misconceptions about the use of hormonal contraception in women with hypertension and a history of venous thrombosis, women with these conditions are likely having their contraceptive options inappropriately constrained. In contrast, the incorrect belief of more than 30% of providers that combined hormonal contraceptives are appropriate for women with migraine with aura may lead to increased risk for stroke in women with this condition.

The finding that gaps in knowledge about contraception was more common among family medicine providers and older providers suggest the need for expanded efforts at education targeting these groups. For older providers, attention to continuing medical education (CME) with emphasis on evidence-based resources, such as the WHO recommendations [12], has the potential to improve knowledge. The lower level of contraceptive knowledge among family medicine providers is consistent with a previous study of residents in obstetrics and gynecology and family medicine [14]. This is not surprising, as several previous studies have found that family medicine residency programs are lacking in contraceptive training [14, 25, 26]. As family medicine providers provide a substantial amount of contraceptive care in the United States [27], a focus on improving contraceptive education in residency programs and CME programs could improve the care provided to women.

Limitations of this study include the use of a convenience sample of providers at meetings of national medical specialty organizations. This bias would likely result in an underestimate of the number of subjects answering questions incorrectly, as providers at these meetings and those willing to volunteer for research may be more informed about evidence-based practice than the general population of providers. Additionally, this study focused on seven specific questions about contraceptive care and did not address all relevant issues in this area. Further research would help illuminate the topics most important for integration into medical education.

The results of this study demonstrate a need for improved medical education efforts to ensure that women are not inappropriately restricted from specific contraceptives, that they do not receive methods that could put them at increased risk for complications and that they can use a method well-suited to their needs so they can avoid unintended pregnancies. Dissemination of evidence-based guidelines, such as the WHO medical eligibility criteria, can help to standardize contraceptive advice so that all women receive quality and evidence-based contraceptive care.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by an anonymous foundation. This project was also supported by NIH?NCRR/OD UCSF-CTSI Grant Number KL2 RR024130. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mosher WD, Martinez GM, Chandra A, Abma JC, Willson SJ. Use of contraception and use of family planning services in the United States: 1982–2002. Adv Data. 2004:1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World contraceptive use. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebrahim SH, Anderson JE, Correa-de-Araujo R, Posner SF, Atrash HK. Overcoming social and health inequalities among U.S women of reproductive age-Challenges to the nation's health in the 21st century. Health Policy. 2009;90:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Culwell KR, Feinglass J. The association of health insurance with use of prescription contraceptives. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2007;39:226–230. doi: 10.1363/3922607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moos MK, Bartholomew NE, Lohr KN. Counseling in the clinical setting to prevent unintended pregnancy: an evidence-based research agenda. Contraception. 2003;67:115–132. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(02)00472-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.RamaRao S, Lacuesta M, Costello M, Pangolibay B, Jones H. The link between quality of care and contraceptive use. Int Fam Plann Perspect. 2003;29:76–83. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.29.076.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lei ZW, Wu SC, Garceau RJ, et al. Effect of pretreatment counseling on discontinuation rates in Chinese women given depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate for contraception. Contraception. 1996;53:357–361. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(96)00085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koenig MA, Hossain MB, Whittaker M. The influence of quality of care upon contraceptive use in rural Bangladesh. Stud Fam Plann. 1997;28:278–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isaacs JN, Creinin MD. Miscommunication between healthcare providers and patients may result in unplanned pregnancies. Contraception. 2003;68:373–376. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rowlands S. New technologies in contraception. BJOG. 2009;116:230–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harper CC, Blum M, de Bocanegra HT, et al. Challenges in translating evidence to practice: the provision of intrauterine contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1359–1369. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318173fd83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. 4th edition. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stubbs E, Schamp A. The evidence is in. Why are IUDs still out?: family physicians' perceptions of risk and indications. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:560–566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schreiber CA, Harwood BJ, Switzer GE, Creinin MD, Reeves MF, Ness RB. Training and attitudes about contraceptive management across primary care specialties: a survey of graduating residents. Contraception. 2006;73:618–622. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hubacher D, Lara-Ricalde R, Taylor DJ, Guerra-Infante F, Guzman-Rodriguez R. Use of copper intrauterine devices and the risk of tubal infertility among nulligravid women. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:561–567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farley TM, Rosenberg MJ, Rowe PJ, Chen JH, Meirik O. Intrauterine devices and pelvic inflammatory disease: an international perspective. Lancet. 1992;339:785–788. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91904-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Ding J, et al. Low dose mifepristone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1803–1810. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11767-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carolei A, Marini C, De Matteis G. History of migraine and risk of cerebral ischaemia in young adults. The Italian National Research Council Study Group on Stroke in the Young. Lancet. 1996;347:1503–1506. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90669-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ACOG practice bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 59, January 2005. Intrauterine device. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:223–232. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200501000-00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cardiovascular disease use of oral and injectable progestogen-only contraceptives and combined injectable contraceptives. Results of an international, multicenter, case-control study. World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Contraception. 1998;57:315–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jick S, Kaye JA, Li L, Jick H. Further results on the risk of nonfatal venous thromboembolism in users of the contraceptive transdermal patch compared to users of oral contraceptives containing norgestimate and 35 microg of ethinyl estradiol. Contraception. 2007;76:4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jick SS, Kaye JA, Russmann S, Jick H. Risk of nonfatal venous thromboembolism in women using a contraceptive transdermal patch and oral contraceptives containing norgestimate and 35 microg of ethinyl estradiol. Contraception. 2006;73:223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cole JA, Norman H, Doherty M, Walker AM. Venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and stroke among transdermal contraceptive system users. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:339–346. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000250968.82370.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank ML, Bateman L, Poindexter AN. The attitudes of clinic staff as factors in women's selection of Norplant implants for their contraception. Women Health. 1994;21:75–88. doi: 10.1300/J013v21n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steinauer JE, DePineres T, Robert AM, Westfall J, Darney P. Training family practice residents in abortion and other reproductive health care: a nationwide survey. Fam Plann Perspect. 1997;29:222–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nothnagle M, Prine L, Goodman S. Benefits of comprehensive reproductive health education in family medicine residency. Fam Med. 2008;40:204–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scholle SH, Chang JC, Harman J, McNeil M. Trends in women's health services by type of physician seen: data from the 1985 and 1997–98 NAMCS. Womens Health Issues. 2002;12:165–177. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(02)00139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]