Abstract

Eukaryotic cells express a wide variety of endogenous small regulatory RNAs that regulate heterochromatin formation, developmental timing, defense against parasitic nucleic acids, and genome rearrangement. Many small regulatory RNAs are thought to function in nuclei 1-2. For instance, in plants and fungi siRNAs associate with nascent transcripts and direct chromatin and/or DNA modifications 1-2. To further understand the biological roles of small regulatory RNAs, we conducted a genetic screen to identify factors required for RNA interference (RNAi) in C. elegans nuclei 3. Here we show that nrde-2 encodes an evolutionarily conserved protein that is required for small interfering (si)RNA-mediated silencing in nuclei. NRDE-2 associates with the Argonaute protein NRDE-3 within nuclei and is recruited by NRDE-3/siRNA complexes to nascent transcripts that have been targeted by RNAi. We find that nuclear-localized siRNAs direct a NRDE-2-dependent silencing of pre-mRNAs 3’ to sites of RNAi, a NRDE-2-dependent accumulation of RNA Polymerase (RNAP) II at genomic loci targeted by RNAi, and NRDE-2-dependent decreases in RNAP II occupancy and RNAP II transcriptional activity 3’ to sites of RNAi. These results define NRDE-2 as a component of the nuclear RNAi machinery and demonstrate that metazoan siRNAs can silence nuclear-localized RNAs co-transcriptionally. In addition, these results establish a novel mode of RNAP II regulation; siRNA-directed recruitment of NRDE factors that inhibit RNAP II during the elongation phase of transcription.

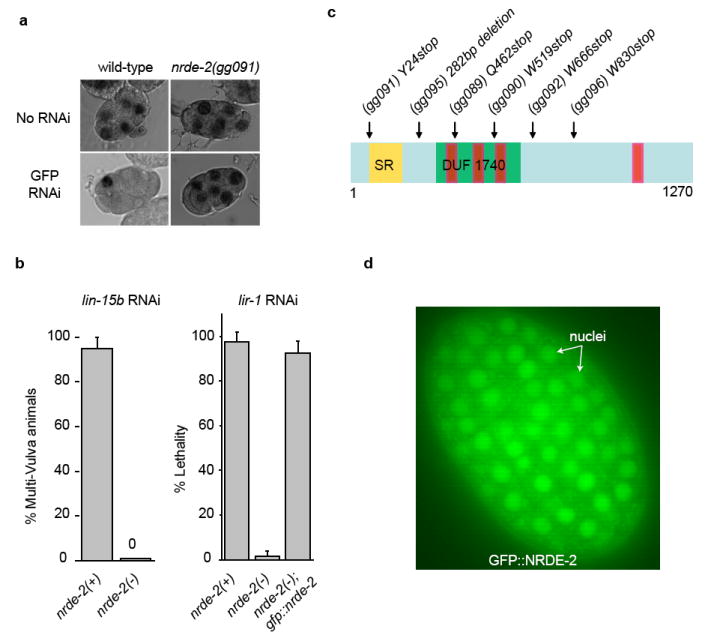

We previously described a forward genetic screen for factors required for RNA interference (RNAi) in C. elegans nuclei 3. This screen identified the Argonaute (Ago) protein NRDE-3, which transports siRNAs from the cytoplasm to the nucleus 3. Here we report that this screen identified twenty-eight mutant alleles defining the gene nuclear RNAi defective-2 (nrde-2). nrde-2 was required for RNAi processes within nuclei. For instance, wild-type C. elegans animals silence the nuclear-retained pes-10∷GFP mRNA following exposure to dsRNA targeting this pes-10∷GFP mRNA (GFP RNAi) 3,4. nrde-2 mutant animals failed to silence the pes-10∷GFP mRNA following GFP RNAi, indicating that a wild-type copy of nrde-2 is required for dsRNA-mediated silencing of this nuclear-localized RNA (Fig. 1a and Fig. S2). The lin-15b and lin-15a genes are expressed as a bicistronic RNA, which is separated into distinct lin-15b and lin-15a RNAs within the nucleus. Animals lacking both lin-15b and lin-15a, but not either gene product alone, exhibit a multi-vulva (Muv) phenotype 5,6. RNAi targeting lin-15b alone is sufficient to induce a Muv phenotype, arguing that nuclear-localized lin-15b/a RNA can be silenced by RNAi 3. nrde-2(-) animals failed to exhibit a Muv phenotype in response to lin-15b RNAi (Fig. 1b). Similarly, NRDE-2 was required for silencing the nuclear-localized lir-1/lin-26 polycistronic RNA (Fig. 1b, and materials and methods). Thus, NRDE-2 is required for RNAi-based silencing of these nuclear-localized RNAs.

Figure 1. nrde-2 encodes a conserved and nuclear-localized protein that is required for nuclear RNAi.

(a) Light microscopy of ≈6-cell embryos +/- GFP RNAi subjected to in situ hybridization detecting pes-10∷gfp RNA. (b) nrde-2(-) animals fail to silence the lin-15b/lin15a and lir-1/lin-26 nuclear-localized RNAs (n=4, +/- s.d.). An eri-1(-) genetic background was used for this analysis (c) Predicted domain structure of NRDE-2. (Yellow) SR domain. (Green) DUF1740. (Red) potential HAT-like repeats. (d) Fluorescent microscopy of a ≈200 cell embryo expressing a rescuing GFP∷NRDE-2 fusion protein.

To determine the molecular identity of nrde-2 we mapped nrde-2 to a genetic interval containing the gene T01E8.5. Sequencing of T01E8.5 from six independent nrde-2 mutant strains identified six mutations in T01E8.5 (Fig. 1c). Transformation of wild-type T01E8.5 DNA into nrde-2 mutant animals rescued nrde-2 mutant phenotypes (Fig. 1b). Thus, T01E8.5 corresponds to nrde-2. nrde-2 encodes an ≈130 kDa protein (NRDE-2) containing a conserved domain of unknown function (DUF) 1740, and two domains frequently found in RNA processing factors; a serine/arginine (SR) rich domain, and half-a-tetratricopeptide (HAT)-like domains (Fig. 1c, and Fig. S3). A single putative orthologue of NRDE-2 was found in plant, fission yeast, insect, and mammalian genomes 7. A fusion gene between GFP and NRDE-2 (GFP∷NRDE-2), which was sufficient to rescue nrde-2(-) mutant phenotypes (Fig. 1b), localized predominantly to the nucleus (Fig. 1d). Finally, animals harboring putative null alleles of nrde-2 produce ≈ 25% the number of progeny as wild-type animals (Fig. S4). We conclude that nrde-2 encodes a conserved and nuclear-localized protein that is important for fecundity and is required for nuclear RNAi.

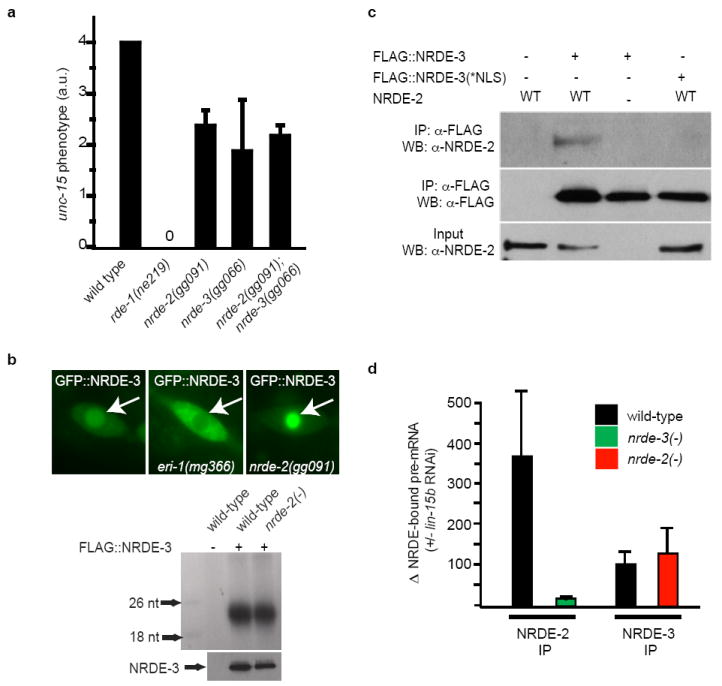

We sought to clarify the relationship between NRDE-2 and the Ago protein NRDE-3. Genetic analyses demonstrated that nrde-2 and nrde-3 function in the same genetic pathway (Fig. 2a). NRDE-2, however, was not required for NRDE-3 to transport siRNAs from the cytoplasm to the nucleus; NRDE-3 bound siRNAs, and in response to siRNA binding, localized to the nucleus similarly in both nrde-2(+) and nrde-2(-) animals (Fig. 2b). These data suggest that NRDE-2 may function downstream of NRDE-3-mediated siRNA transport during nuclear RNAi. In support of this hypothesis, we observed a weak, but reproducible, association between NRDE-3 and NRDE-2; NRDE-3 co-precipitated 0.1% to 0.5% of the total cellular pool of NRDE-2 (Fig. 2c). Conversely, NRDE-3 co-precipitated with NRDE-2 (Fig. S5). A NRDE-3 variant harboring mutations within its nuclear localization signal (termed NRDE-3(*NLS)) localizes constitutively to the cytoplasm 3. NRDE-2 did not co-precipitate with NRDE-3(*NLS) (Fig. 2c). Taken together, these data argue that NRDE-2 functions downstream of NRDE-3/siRNA transport in the nuclear RNAi pathway and associates with NRDE-3 in the nucleus.

Figure 2. NRDE-2 is recruited by NRDE-3/siRNA complexes to pre-mRNAs that have been targeted by RNAi.

(a) Animals were exposed to unc-15 dsRNA and scored for uncoordinated phenotypes (Unc) (n=3, +/- s.d.). rde-1(ne219) animals are defective for RNAi 12. (b) (top panels) Fluorescent microscopy of a seam cell expressing GFP∷NRDE-3. Arrows indicate nuclei. eri-1(mg366) animals fail to express endo siRNAs and consequently NRDE-3 is mislocalized to the cytoplasm 3,13,14. (bottom panels) FLAG∷NRDE-3 co-precipitating RNAs 32P-radiolabeled and analyzed by PAGE. (c) NRDE-2 co-precipitates with nuclear-localized NRDE-3 (materials and methods) (n=3). (d) qRT-PCR quantification of NRDE-2/3 co-precipitating pre-mRNA. Throughout this manuscript pre-mRNA levels are quantified with exon/intron or intron/intron primer pairs. Data are expressed as ratios of co-precipitating pre-mRNA +/- lin-15b RNAi (n=4 for NRDE-2 IP, n=2 for NRDE-3 IP, +/- s.e.m.). Δ=fold change.

siRNAs direct NRDE-3 to bind pre-mRNAs that have been targeted by RNAi. For instance, following RNAi targeting lir-1, unc-40, or dpy-28, we detected a >200-fold increase in the amount of lir-1, unc-40, or dpy-28 pre-mRNA that co-precipitated with NRDE-3, respectively (Fig. S6) 3. The RNAi-directed association of NRDE-3 with pre-mRNA depends upon the ability of NRDE-3 to bind siRNAs and the ability of NRDE-3 to localize to the nucleus 3. NRDE-2 was not required for NRDE-3 to associate with pre-mRNA: in nrde-2(+) and nrde-2(-) animals NRDE-3 was recruited to pre-mRNAs with similar efficiency (Fig. 2d). As nrde-2(-) animals are disabled for nuclear RNAi, these data indicate that the recruitment of NRDE-3/siRNA complexes to pre-mRNAs is not sufficient to trigger nuclear silencing. Interestingly, RNAi also directed NRDE-2 to pre-mRNAs; lin-15b RNAi induced a >300-fold increase in the amount of lin-15b pre-mRNA that co-precipitated with NRDE-2 (Fig. 2d). >10-fold less pre-mRNA co-precipitated with NRDE-2 in nrde-3(-) animals than in nrde-3(+) animals, indicating that RNAi directs NRDE-2 to pre-mRNAs in a largely NRDE-3 dependent manner (Fig. 2d). Similar results were obtained when an endogenous mRNA target of the NRDE pathway was analyzed (Fig. S7). Taken together, these data indicate that, following RNAi, NRDE-2 is recruited to pre-mRNAs by NRDE-3, which itself is localized to pre-mRNAs by siRNA/pre-mRNA base pairing.

In order to further our understanding of nuclear RNAi, we conducted a reverse genetic screen for nuclear RNAi factors (Fig. S8). This screen identified nrde-2 and nrde-3, as well as five additional putative nuclear RNAi factors (Fig. S8). Rpb7 is a subunit of RNA Polymerase (RNAP) II that functions in siRNA-mediated heterochromatin formation in S. Pombe 8. Our screen identified the C. elegans orthologue of Rpb7 (rpb-7); RNAi of rpb-7 induced nuclear RNAi defects similar to those induced by RNAi of nrde-2 or nrde-3 (Fig. 3a, and Fig. S8). The identification and characterization of mutant alleles of C. elegans rpb-7 will be required to confirm a role for rpb-7 in C. elegans nuclear RNAi. Nonetheless, these data hint that nuclear RNAi may act concurrently with RNAP II transcription in C. elegans.

Figure 3. C. elegans siRNAs direct a NRDE-2/3-dependent co-transcriptional gene silencing program.

(a) Animals were exposed to one part lir-1 dsRNA expressing bacteria and 6 parts vector control, nrde-2/3, or rpb-7 dsRNA expressing bacteria. (%) indicates percentage of animals that failed to exhibit lir-1 RNAi phenotypes. (b) Chromatin IP with H3K9me3 antibody (Upstate, #07-523). Data are expressed as ratio of H3K9me3 co-precipitating DNA +/- lin-15b RNAi, (n=2). (c) Total RNA was isolated and lin-15b pre-mRNA was quantified with qRT-PCR. Data are expressed as ratios +/- lin-15b RNAi. (c) and (e) were done in an eri-1(-) genetic background. (d) FLAG∷NRDE-2/3 co-precipitating dpy-28 pre-mRNA. Data are expressed as ratio +/- dpy-28 RNAi (n=4, +/- s.d.). (e) Chromatin IP of AMA-1/Rpb1 with α-AMA-1 antibody (Covance, 8WG16). Data are expressed as ratio of AMA-1 co-precipitating DNA +/- lin-15b RNAi (n=3, +/- s.d.).

Five additional lines of investigation cumulatively argue that nuclear RNAi operates during the elongation phase of transcription. First, pre-mRNA splicing is thought to occur co-transcriptionally 9. Therefore, the association of NRDE-2/3 with unspliced RNAs suggests that nuclear RNAi operates near or at the site of transcription (Fig. 2d). Second, we subjected animals undergoing RNAi to chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) detecting tri-methylated (me3) H3K9 and found that RNAi directed a NRDE-2-dependent enrichment of H3K9me3 at a genomic site targeted by RNAi (Fig. 3b and Fig. S9). These data establish that, as in other organisms, C. elegans siRNAs direct H3K9 methylation, and support the idea that nuclear RNAi in C. elegans operates in close proximity to the site of transcription. Third, we isolated RNA from animals subjected to RNAi targeting lin-15b, lir-1, or dpy-28 and measured pre-mRNA abundance at multiple sites distributed across the length of these pre-mRNAs, respectively. RNAi resulted in NRDE-2 dependent silencing of these pre-mRNAs 3’ to the site of RNAi (Fig. 3c and Fig. S10). These data argue that nuclear RNAi is unlikely to occur at the initiation phase of transcription. Rather, these data argue that nuclear RNAi operates during transcription elongation. Incidentally, these data also show that, for unknown reasons, the relative contribution of the nuclear RNAi pathway to overall RNAi-based silencing can vary, depending on the gene targeted by RNAi (Fig. S10c) 3. Fourth, following bouts of dpy-28 RNAi, NRDE-2 and NRDE-3 associated with dpy-28 pre-mRNA fragments encoded upstream (5’) of the site of RNAi with >200 fold greater efficacy than sequences encoded downstream (3’) of the site of RNAi (Fig. 3d). Similar results were obtained following lin-15b, lir-1, and unc-40 RNAi (Fig. S11). Nuclear silencing events were required for the preferential association of NRDE-3 with 5’ pre-mRNA fragments; in nrde-2(-) animals, NRDE-3 associated with pre-mRNA sequences encoded both 5’ and 3’ to the site of RNAi with equal efficiency (Fig. S11c). These data support the idea that nuclear RNAi silences pre-mRNAs during the elongation phase of transcription, and suggest that NRDE-2/3 remain associated with pre-mRNA fragments following silencing. Fifth, we subjected animals undergoing RNAi to Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) targeting the largest subunit of RNAP II, AMA-1/Rpb1. AMA-1/Rpb1 occupancy increased near genomic regions targeted by RNAi (Fig. 3e and Fig. S12). No changes in RNAP II occupancy were observed near sites of transcription initiation. Increases in AMA-1/Rpb1 occupancy were dependent upon NRDE-2; nrde-2(-) animals did not exhibit changes in AMA-1/Rpb1 occupancy following RNAi (Fig. 3e and Fig. S12). Thus, RNAi elicits NRDE-2-dependent increases in AMA-1/Rpb1 occupancy at or near genomic sites targeted by RNAi, arguing that siRNAs regulate RNAP II elongation. Taken together, these data indicate that C. elegans siRNAs, acting in conjunction with NRDE-2/3, silence nascent transcripts during the elongation phase of transcription.

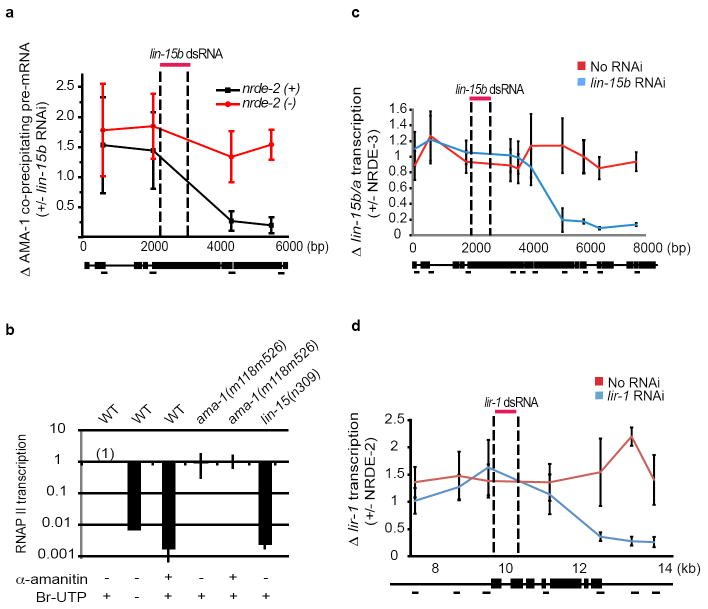

Interestingly, we detected a decrease in AMA-1/Rpb1 occupancy downstream of the site of lin-15b (and to a lesser extent lir-1) RNAi, suggesting that siRNAs might inhibit RNAP II transcription (Fig. 3e and Fig. S12). Two additional lines of evidence support this hypothesis. First, we quantified lin-15b pre-mRNA associated with RNAP II before and after lin-15b RNAi. This effect was dependent upon NRDE-2, and was observed 3’, but not 5’, to the site of RNAi (Fig. 4a). Second, we established a C. elegans nuclear run-on assay utilizing 5-bromouridine 5’-triphosphate (Br-UTP). This approach detected lin-15b transcription, which was sensitive to the RNAP II inhibitor α-amanitin (Fig. 4b). ama-1(m118m526) encodes a mutant variant of AMA-1/Rbp1 that is resistant to α-amanitin 10. Transcription from ama-1(m118m526) nuclei was insensitive to α-amanitin treatment (Fig. 4b). Finally, lin-15b transcription was not detected when reactions were carried out with nuclei harboring a lin-15b deletion allele (Fig. 4b). Thus, our nuclear run-on assay measures RNAP II-mediated transcription of the lin-15b locus. lin-15b RNAi induced a NRDE-2/3-dependent inhibition of RNAP II transcription 3’ to the site of lin-15b RNAi (Fig. 4c and Fig. S13). siRNA-directed RNAP II inhibition was observed ≈ 2 kb downstream of the site of RNAi, hinting that (following recruitment of NRDE-2) additional molecular events may be required to silence RNAP II. Shifting the location of RNAi towards the 5’ end of the lin-15b gene resulted in a coincident shift in patterns of RNAP II inhibition, indicating that the response of RNAP II to RNAi was sequence directed and sequence specific (Fig. S14). Finally, lir-1 RNAi directed a similar NRDE-2-dependent inhibition of RNAP II transcription downstream of the site of lir-1 RNAi (Fig. 4d). We conclude that siRNAs-direct a NRDE-2/3-dependent inhibition of RNAP II activity that occurs during the elongation phase of transcription. It should be noted that the decreases in RNAP II occupancy and RNAP II activity that we observe 3’ to sites of RNAi argue that siRNAs, acting in conjunction with NRDE-2/3, are likely to terminate RNAP II transcription.

Figure 4. siRNAs direct a NRDE-2/3-dependent inhibition of RNAP II during the elongation phase of transcription.

(a) AMA-1 co-precipitating pre-mRNA. Data are expressed as ratio +/- lin-15b RNAi (n=3, +/- s.d.). (b) A crude preparation of nuclei was subjected to nuclear run-on analysis (see materials and methods). Transcription detected from wild-type (WT) nuclei was defined as one (n=3, +/- s.d.). (c-d) RNAi inhibits RNAP II activity 3’ to sites of RNAi. An eri-1(-) genetic background was used for these analyses. Nuclei isolated from animals treated with lin-15b (c) or lir-1 (d) RNAi were subjected to run-on analysis. Data are expressed as ratio of transcription detected in nrde-3(+)/nrde-3(-) nuclei (c) or nrde-2(+)/nrde-2(-) nuclei (d) (n=5, for c, and n=3 for d, +/- s.e.m.).

Transcription is a highly regulated process. Here we describe a novel mechanism by which transcription can be regulated; small regulatory RNA-dependent recruitment of NRDE factors that inhibit RNAP II during the elongation phase of transcription. Eukaryotic cells express a multitude of small regulatory RNAs and antisense transcripts that are of unknown function. It will be of interest to test whether these RNAs regulate RNAP II via the mechanism described here. The mechanism of nuclear silencing in C. elegans is enigmatic. Many Ago proteins function via endonucleolytic cleavage of target RNAs (slicer activity) 11. The Ago protein NRDE-3 lacks residues required for slicer activity, indicating that nuclear RNAi in C. elegans is unlikely to depend upon NRDE-3-mediated slicing of pre-mRNAs 3,12. We have show that nuclear RNAi silences pre-mRNAs co-transcriptionally and that nuclear RNAi inhibits RNAP II elongation and transcription. Thus, our data suggest a mechanism for nuclear RNAi: siRNA-directed co-transcriptional silencing of RNAP II. Alternatively, the RNAP II inhibition we observe may represent a secondary consequence of another (currently unknown) co-transcriptional silencing activity associated with the Nrde pathway. Finally, NRDE-2 is directed to nascent transcripts by siRNAs and NRDE-2 is required for linking siRNAs to RNAP II inhibition. NRDE-2 is conserved. It will therefore be of interest to assess whether small regulatory RNAs and RNAP II are similarly linked in other metazoans.

Methods Summary

The following strains were used for this work. (YY151) eri-1(mg366); nrde-2(gg091), (YY158) nrde-3(gg066),(YY174) ggIS1[nrde-3p∷3xflag∷gfp∷nrde-3], (YY178) eri-1(mg366); ggIS1, (YY186) nrde-2 (gg091), (YY197) nrde-2(gg091); axIs36[pes-10∷gfp], (YY229) nrde-2(gg091); ggIS1, (YY258) nrde-2(gg091); nrde-3(gg066), (YY298) nrde-3(gg066); ggIS24[nrde-3p∷3xflag∷gfp∷nrde-3*nls], (YY323) eri-1(mg366); nrde-2(gg091); unc-119(ed3); ggIS28[nrde-3p∷3xflag∷gfp∷nrde-2], (YY346), nrde-2(gg091); ggIS28, (YY353) nrde-2(gg091); ggIS1; ggIS36[nrde-3p∷3xha∷gfp∷nrde-2], (YY363) nrde-3(gg066); nrde-2(gg091); ggIS28, (GR1373) eri-1(mg366), (wm27) rde-1(ne219), (DR1099) ama-1(m118m526), (MT309) lin-15AB(n309), (JH103) axIs36. Worm culture conditions, plasmid construction, feeding RNAi assay, lir-1 RNAi assay, RNA in situ hybridization, fluorescence imaging, cDNA preparation, NRDE-2/3 co-precipitation, RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP), RNA isolation, quantitative real time PCR, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), and nuclear run-on (NRO) assays are described in detail in Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Phil Anderson, members of the Anderson lab, David Wassarman, and David Brow for comments, and the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC) for strains. This work was supported by grants from the PEW and Shaw scholars programs, the NIH, and the AHA.

Footnotes

Author Contributions. S.G. performed genetic screening, generated constructs, and contributed Figs. 1a, 2b-c, 3b, 3e, 4a, s2, s6, s7, and s9-12. A.B. mapped nrde-2, generated transgenic lines, and contributed Figs. 1c-d, s3, and s5. K.B. contributed Figs. 1b, s7, and s3. N.B. contributed to Figs. 3a and s7. D.P. contributed Fig. 2a. S.K. wrote the paper and contributed Figs. 2d, 3c-d, 4b-d, s1, s2, s13, and s14.

Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature. A figure (S1) summarizing the main result of this paper is available in supplementary information.

Author information. NRDE-2 accession number is NP_496209. Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Matzke MA, Birchler JA. RNAi-mediated pathways in the nucleus. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6(1):24–35. doi: 10.1038/nrg1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moazed D. Small RNAs in transcriptional gene silencing and genome defence. Nature. 2009;457(7228):413–20. doi: 10.1038/nature07756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guang S, Bochner AF, Pavelec DM, et al. An Argonaute transports siRNAs from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Science. 2008;321(5888):537–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1157647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montgomery MK, Xu S, Fire A. RNA as a target of double-stranded RNA-mediated genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(26):15502–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark SG, Lu X, Horvitz HR. The Caenorhabditis elegans locus lin-15, a negative regulator of a tyrosine kinase signaling pathway, encodes two different proteins. Genetics. 1994;137(4):987–97. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.4.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang LS, Tzou P, Sternberg PW. The lin-15 locus encodes two negative regulators of Caenorhabditis elegans vulval development. Mol Biol Cell. 1994;5(4):395–411. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.4.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tatusov RL, Fedorova ND, Jackson JD, et al. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:41–55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Djupedal I, Portoso M, Spahr H, et al. RNA Pol II subunit Rpb7 promotes centromeric transcription and RNAi-directed chromatin silencing. Genes & Development. 2005;19(19):2301–6. doi: 10.1101/gad.344205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore MJ, Proudfoot NJ. Pre-mRNA processing reaches back to transcription and ahead to translation. Cell. 2009;136(4):688–700. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogalski TM, Golomb M, Riddle DL. Mutant Caenorhabditis elegans RNA polymerase II with a 20,000-fold reduced sensitivity to alpha-amanitin. Genetics. 1990;126(4):889–98. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.4.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J, Carmell MA, Rivas FV, et al. Argonaute2 is the catalytic engine of mammalian RNAi. Science. 2004;305(5689):1437–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1102513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yigit E, Batista PJ, Bei Y, et al. Analysis of the C. elegans Argonaute family reveals that distinct Argonautes act sequentially during RNAi. Cell. 2006;127(4):747–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duchaine TF, Wohlschlegel JA, Kennedy S, et al. Functional proteomics reveals the biochemical niche of C. elegans DCR-1 in multiple small-RNA-mediated pathways. Cell. 2006;124(2):343–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee RC, Hammell CM, Ambros V. Interacting endogenous and exogenous RNAi pathways in Caenorhabditis elegans. RNA. 2006;12(4):589–97. doi: 10.1261/rna.2231506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.