Abstract

Implementation of electronic health records (EHR), particularly computerized physician/provider order entry systems (CPOE), is often met with resistance. Influence presented at the right time, in the right manner, may minimize resistance or at least limit the risk of complete system failure. Combining established theories on power, influence tactics, and resistance, we developed the Ranked Levels of Influence model. Applying it to documented examples of EHR/CPOE failures at Cedars-Sinai and Kaiser Permanente in Hawaii, we evaluated the influence applied, the resistance encountered, and the resulting risk to the system implementation. Using the Ranked Levels of Influence model as a guideline, we demonstrate that these system failures were associated with the use of hard influence tactics that resulted in higher levels of resistance. We suggest that when influence tactics remain at the soft tactics level, the level of resistance stabilizes or de-escalates and the system can be saved.

Keywords: power, resistance, influence, electronic health records, clinical informatics, socio-technical, human factors, hospital information systems, medical order entry systems

I. INTRODUCTION

EHR/CPOE systems have great potential to improve quality of care and patient safety[1–3], but this benefit is not always being realized because many EHR/CPOE efforts encounter difficulty or fail[4–6]. Many of these failures and problems are traced back to user resistance[7, 8]. Thus information technology leaders are faced with the problem of what to do about resistance.

Many theories and models have been proposed regarding the relationship of power, influence, and resistance, but none have combined these various models into a working tool for minimizing resistance to the introduction of information technology. Because of the strong power struggle between clinicians and implementers of CPOE, healthcare is especially in need of research in this area. The purpose of this model is to provide such a working tool for effectively managing resistance in the implementation of CPOE.

II. BACKGROUND

The word “power” is an emotionally-laden and socially charged word. We criticize those who have it, we feel it’s wrong to seek it, yet we always wish we had it. It is often socially unacceptable to explicitly want power, and just as socially unacceptable to not have it.

The important realization is that everyone has power in varying degrees, based on the situation they are in, and the position that they hold in that situation. All individuals hold a level of power in their work environment, some more than others. When that power is threatened by the implementation of information technology (IT) in the workplace, any users will likely resist.

Physicians are generally considered to be among the most powerful users of IT so their resistance is considered a major barrier to overcome when implementing IT[7, 8]. They are frequently in opposition to the chief medical information officer (CMIO) whose job is to apply influence on the clinical users to minimize resistance and elicit support for the new IT. This is a difficult task for the CMIO and guidelines that can be used to maximize the effects of influence are needed.

Being able to predict the reaction to certain types of influence offers the person or group doing the influencing an advantage. We combined French and Raven’s social power bases[9], Bruins and Kipnis’ models of influence[10, 11], and Coetsee’s levels of resistance as defined by Lapointe and Rivard[12] into a progressive, ranked order, matching influence tactics with the expected resistance. Ranking and matching influence tactics with the types of resistance is a new concept, but the expectation of resistance to influence is not.

In 1938, Kurt Lewin theorized a relationship between power and resistance within groups. His concept suggested that power from persons in superior positions emanated like concentric circles, or “power fields” from the person with power, and encompassed those who fell within the range of those circles[13]. Since all people have their own power, resistance comes from the power of the person “encompassed” who does not wish to be influenced by the more powerful person. The “encompassed” individual emanates his own concentric circles in the opposite direction. Lewin’s theory has implications for the relationship between influence and resistance. Later, Lewin proposed that groups held much more power than individuals and could provide greater resistance to a change of the status quo[13]. Forming a coalition is one of the strongest forms of resistance (e.g. labor unions).

Expanding on Lewin’s theories, John French and Lester Coch found that standards within worker groups or coalitions were in opposition to management’s requests unless the workers moved out of their own power field and into a cooperative arrangement with management – basically they became part of management’s power field[14]. Therefore, the goal of an “influencer” (the person doing the influencing) is to move the “target” (person or persons being influenced) into the influencer’s power field – incorporating them into the influencer’s coalition.

For the first half of the paper, we first review the four theories of power, providing details of power facet classification and their relationships to influence tactics. In the second half of the paper we use these theories to develop our Ranked Levels of Influence Model and apply it to two well known cases of IT implementation failure.

A. French and Raven’s Six Power Bases

Even though the terms power and influence are often used interchangeably, they represent different concepts. Power is the “potential” to influence someone, but influence is the “actual use” of that power[15, 16]. In their work on interpersonal power and influence, John French and Bertram Raven identified six bases of social power[9, 17–19]. These six bases of social power are as follows:

Legitimate – power based on one’s formal position within an organization, reciprocity, equity for suffering incurred, or dependence on someone else for help

Coercive – power based on the ability to provide rejection, disapproval or physical threats

Reward – power based on the ability to provide acceptance, approval or tangible rewards

Expert – power based on one’s knowledge and/or experience

Referent – power based on people’s sense of identification or desire for identification with the influencing person, charisma

Informational – power based on the ability to persuade or provide information to allow someone to make a decision

These six bases of power are the foundation for the power an individual has available to influence another person. Each base of power has related forms of influence that can be used to effect a change in the target person, illustrated in Table 1. This is referred to as the “Power Interaction Model[18].”

Table 1.

| Base of Power | Form of Influence | Example of Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Reward | Impersonal reward | Give something desired |

| Personal reward | Receive personal approval from someone liked or valued highly | |

| Coercion | Impersonal coercion | Impose punishment |

| Personal coercion | Threaten rejection or disapproval from someone valued highly | |

| Legitimacy | Position power | Tell/ask to do something because they are your boss/superior |

| Reciprocity | Oblige someone to do something because you did something for them | |

| Responsibility or dependence | Depend on someone to do something because they are the only one who can do it | |

| Equity (compensatory) | Oblige someone to do something to make up for pain or difficulty they caused | |

| Expertise | Positive | Inform someone how something should be done because of your previous experience with it or knowledge |

| Negative | Imply that someone does not know as much about this as you do | |

| Reference | Positive | Mimic or model yourself after someone |

| Negative | Do the opposite of what someone does or recommends due to unattractive actions or negative feelings toward them. | |

| Informational | Direct | Explain the reason using logical arguments that this is the case, to help someone understand |

| Indirect | Overhear a conversation or mention a similar case |

Each power base can be expressed with multiple types of influence which can be characterized as: direct vs. indirect, personal vs. impersonal, and positive vs. negative. Because the choice of influence has social implications, it is important to understand how we chose the type of influence to use.

B. Kipnis’ model of influence

A theory of influence that was later named “The Power Act Model” in an article by Bruins[10] was developed in 1976 by Kipnis[11]. The Power Act Model suggests that an individual makes a choice regarding the type of influence to use based on certain features of the situation. These features are 1) the resources (i.e. power) the individual has at their disposal, 2) the individual’s inhibition to actually use a power base and 3) the amount of resistance that they expect from the target person if they attempt to influence them[10].

There are eight categories of tactics that can be used in this model. They are assertiveness, ingratiation, rationality, sanctions, exchange, upward appeal, blocking and coalition[11]. Examples of influence tactics representing each category are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Kipnis’ Power Act Model of Tactics[11]

| Influence Category | Influence Tactics |

|---|---|

| Assertiveness | Demand, order, set deadlines |

| Ingratiation | Make the other person feel important |

| Rationality | Write a plan, explain the reasons |

| Sanctions | Threaten job security, financial coercion |

| Exchange | Offer an exchange of favors, personal sacrifice |

| Upward appeal | Invoke the influence of higher levels in organization |

| Blocking | Stop target person from carrying out some action |

| Coalition | Steady pressure for compliance by obtaining support |

Kipnis also suggested that when stronger types of influence are used (e.g. assertiveness, sanctions, upward appeal, and blocking) it leads to a more negative evaluation of the target by the influencer[11]. This is because the stronger types of influence establish a hierarchy or superior/subordinate relationship, denoted by the ability of the influencer to demand, threaten, or go to higher levels in the organization, rather than a peer relationship of explanation, exchange of favors or providing a feeling of importance.

C. Bruins’ Power Use Model

The “Power Use Model” was developed by condensing Kipnis’ approach[10]. Also based on Raven’s Power Interaction Model, this model identifies influence tactics only as “soft” or “hard” based on the amount of freedom that the target has to either yield or resist. Soft influence tactics were generally used for people within their own group, whereas hard tactics are used with people in groups outside of their own group. Group inclusion is based on psychological contexts of the situation, such as a peer or superior/subordinate relationship.

The Power Use Model suggests that the combination of whether the target yielded or resisted coupled with the level of influence tactic used (hard or soft) reflects the perception of the group relationship between the influencer and the target and impacts future influence attempts[10].

D. Types of Change Behavior

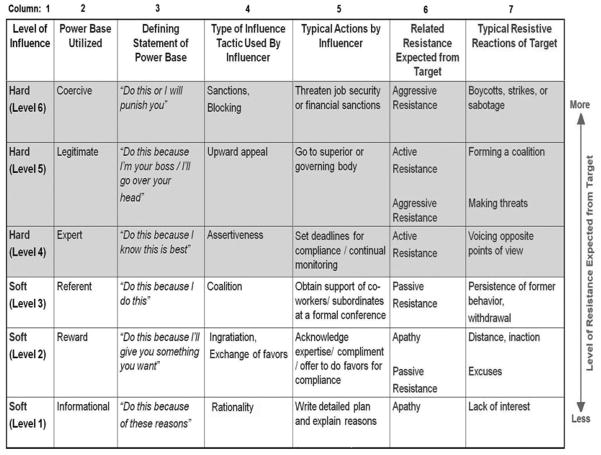

Just as there are different types of influence, there are different types of change behavior. In 1999, Leon Coetsee studied organizational development change and proposed a model of resistive and accepting behavior that exists along a continuum with apathy as the transition point[20]. This model indicates that individuals can respond to a change with varying degree of acceptance or resistance, each of which may be more or less acceptable to the influencer. A model of the continuum is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Coetsee’s Continuum of Acceptance and Resistance[20]

In the case of healthcare IT, achieving increasing levels of acceptance that will elicit acceptance from others is the desired outcome, but simply supporting the system by using it is the minimum acceptable goal of the influencer. On the other hand, resistive behavior left unchecked can escalate to disastrous proportions causing system failure.

In 2005, Lapointe and Rivard, focusing on resistive behavior, re-defined these levels of resistance in terms of their application to the implementation of information technology[12]. They focused on the approach that group behaviors emerge from individual behaviors. Table 3 shows the relationship between Coetsee’s levels of resistance and Lapointe and Rivard’s observed resistive behavior.

Table 3.

| Coetsee’s Levels of Resistance | Lapointe and Rivard’s Resistive Behavior |

|---|---|

| Apathy (Neutral point, passive resignation) | Inaction, distance, lack of interest |

| Passive Resistance (Mild or weak opposition) | Delay tactics, excuses, persistence of former behavior, withdrawal |

| Active Resistance (Strong, but not destructive opposing behavior) | Voicing opposite points of view, asking others to intervene or forming a coalition |

| Aggressive Resistance (Destructive opposing behavior) | Infighting, making threats, strikes, boycotts or sabotage |

Influence that can change the direction along the continuum away from resistance and back toward acceptance should intervene in the weaker levels of resistance before the formation of an opposing coalition.

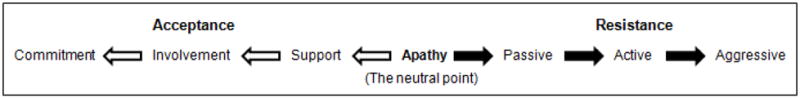

III. FORMULATION OF THE MODEL

Models of power and influence have been discussed separately and in combination, but they have not been combined into a single relationship with resistance. Merging French and Ravens model of social power bases[9], Bruin’s[10] and Kipnis’[11] models of influence and Lapointe and Rivard’s resistive behavior[12], we created the Ranked Levels of Influence Model[21]. This model provides a guideline for CIO’s, system champions, and administrators that illustrates the expected resistive response when using various influence techniques (See Figure 2). This model also indicates at which levels applications of influence may result in individuals moving from passive resistance to active resistance.

Figure 2.

Ranked Levels of Influence[21]

IV. MODEL DESCRIPTION

Beginning from the left side of the model, we start with tactics (column 1) and the power bases that they relate to (column 2). Soft tactics are matched up with power bases that allow the target to make up their own mind (informational power), provide some type of benefit (reward power), or indicate a positive association with someone or some group (referent power). Hard tactics are associated with more direct influence based on superior knowledge or expertise (expert power), superior/subordinate relationships (legitimate power), or threats (coercive power).

Bruins’ stated that soft tactics are used for persons perceived to be in the group, but they are also geared toward influencing the individual to become part of the influencer’s group or coalition. To encourage group affiliation, soft tactics engage the target in persuasive dialog, encourage the target to identify with the other group members, and entice the target. Hard tactics are resorted to when the target is presumed as not being part of the common group or as being part of an opposing coalition. Hard tactics tend to discourage group membership by imposing behavior on the target rather than soliciting it. Column 3 contains a brief statement clarifying the type of power being exerted by that power base. This is provided to ensure that the influencer is aware of what the use of that power is saying to the target.

Columns 4 and 5 link the type of power to types of influence and the specific tactics or actions used to exert that influence. We use the eight categories of influence tactics to directly associate influence with the six power bases. There is a link between the rationality tactic and informational power because both provide the target with explanations that allow the opportunity to make his/her own decision. Ingratiation and reward power fall into the same category because they both attempt to acquire the good graces of the target through a conscious effort or favor. The tactic of formation of a coalition and identifying with a person or group indicated by referent power are also linked. These tactics can be considered soft tactics because they relate to actions performed by influencers attempting to attract the targets into their coalition or group. The targets are considered peers when soft tactics are used. More aggressive categories of influence such as assertiveness can be associated with knowledge or expertise coming from expert power, while upward appeal tactics are associated with the hierarchy coming from legitimate power. Ultimately, sanctions and blocking are the tactics used when coercive power is the method of maximum control. These aggressive tactics are considered hard tactics because they are exerted on targets that are not considered to be in the same group, but are in a competing or even subservient group.

Escalating resistance can be matched with the escalating types of influence. Columns 6 and 7 reflect the types of resistance and their associated reactions as identified by Lapointe and Rivard. Apathy is the neutral zone where the target may either be influenced in a positive or negative manner and is the starting point of the resistance level in our model. Until the target has become affiliated with one group or the other, soft tactics elicit the least amount of resistance which would include lack of interest, excuses, distance/inaction or simply persistence of their previous behavior. Since these behaviors are still passive, soft tactics can provide the influence to move the target into the influencer’s group. However, once hard tactics are initiated, the target is unlikely to remain passively resistant to the influence and may begin to be vocal with opposite opinions or threats, form an opposing coalition, or as an extreme action boycott or sabotage the change. This negatively reflects being perceived as a subservient group. Coalitions or groups are much stronger than individuals and group membership is an important factor with relation to influence and resistance. With soft tactics, the influencer is attempting to form a coalition with the target, but with hard tactics, the target is pushed to form a coalition opposing the influencer.

The critical point in using influence is where soft tactics and hard tactics meet. The influencer must be aware when the midpoint of the model has been reached because it may not be possible to move back into soft tactics once hard tactics have been initiated.

V. APPLICATION TO CASES

Applying the model to documented cases of CPOE implementation failure, demonstrates how various types of influence impact resistive behavior. Because failures of CPOE implementation are rarely published, it was difficult to locate cases that openly identify clinician resistance as the major factor impacting the failure. The two cases used for application of the model were selected because they supplied detailed, temporal information, are familiar to the readers and identified clinician resistance as the cause of the failure. These characteristics allow them to act as critical cases[22], illustrating the potential usefulness of the model while also allowing for critical evaluation and potential rejection of its applicability. The model provides a framework to understand why some influence tactics work while others fail, resulting in the irreconcilable differences leading to system failure.

A. Cedars-Sinai

To prepare this case and analysis of the Cedars-Sinai CPOE implementation failure, we drew from multiple sources. While it limits the analysis of the case to the actions and outcomes that were documented in these sources, the use of multiple sources decreases the likelihood of presentation biases which are common in cases of unsuccessful organizational initiatives. The model can only be applied to those actions that were documented in these sources.

1) Summary of documented facts

With the intent to improve patient care, enhance performance and to meet the standard for CPOE outlined by the Leapfrog project, Cedars-Sinai set out to purchase a clinical system[23, 24]. They examined various commercial products that were available, but did not find any that met their needs. They built their own system called Patient Care Expert (PCX) at a cost of $34 million over a 3 year time frame[4, 24]. Administration determined that physician use of the CPOE system would be mandatory and demonstrated their commitment to this mandate by suspending privileges of 150 attending physicians (out of more than 2000) who were not certified by the start of the CPOE implementation in October 2002[24].

Physicians voiced opinions that this action was punitive and unfair, but administration felt that a single level of patient care should be adhered to throughout the hospital[24]. Over the next four months, physicians expressed their concerns about the additional time required, the lack of usability of the system, unnecessary alerts, and the less than optimal working knowledge that physicians had with the system[4, 24, 25]. Ultimately, at the end of January, 2003, several hundred physicians voted to suspend usage of the system[4]. Even though CPOE was operational for more than two thirds of the inpatients with an aggregate of 700,000 orders placed for over 7000 patients, the hospital board of directors suspended the physician order entry portion of the system with plans to reexamine at the issues and continue implementation in the future[24]. By 2005, the physician overseeing safety procedures indicated that additional layers of staff are used to double and triple check procedures to ensure safety rather than re-attempting CPOE at this time even though it could be better done electronically[4]. In 2009, the statement on the Cedars-Sinai web site states, “Cedars-Sinai Medical Center has partially met these standards [for CPOE implementation] and continues to make progress toward complete compliance[23].” CPOE has yet to be re-attempted at Cedars-Sinai.

2) Application of the Model

At the beginning of the selection process, administration engaged clinicians in the decision of whether to buy or build a system by using informational power and the soft tactics based on rationality. They included the clinicians in the decision group and treated them as peers in this process. It would appear that this continued through the development process for three years and through the pilot project on an obstetrical unit that included 140 physicians[24]. Their feedback was used to initiate revisions to the system and these physicians continued to be treated as peers and part of the group. However, at this point, the majority of the physicians in the organization were apathetic to the process because they were not actively involved.

In order for PCX to be successful and meet the criteria for its development, administration believed that all physicians must participate in CPOE without exception. Administration moved to hard tactics by mandating 100% physician compliance with certification in CPOE use by a specified deadline. Utilizing the expert power base by mandating compliance by a deadline, administration used assertive influence which indicated that they, rather than physicians, knew what was best for the quality of patient care across the organization. The majority of physicians (more than 2000) remained apathetic to the system, but did comply with the training and certification. However, by their own inaction, 150 physicians did not obtain certification. Moving to a coercive power base, administration escalated the hard influence tactics to “sanctions” by using the punitive tactics of suspending those 150 physicians who did not comply with certification.

As a result, physicians, who until this point had been apathetic and compliant, began to exhibit escalated signs of active resistance by voicing opposing opinions that this action was unfair, and initiating “urban legends” around the system. In one case, a physician with 25 years on staff and an opinion leader of the opposition, wrote a scathing letter to administration stating that administration’s implementation report on the system was “disingenuous, inaccurate, replete with half-truths, innuendo, mischaracterizations and good old-fashioned spin[26].”

It would appear that administration maintained their stance on mandatory certification, so the physicians progressed to aggressive resistance by forming a coalition of several hundred physicians who voted to boycott the system by suspending its use[4]. Even though it was only a portion of the physician population, the coalition was powerful enough to cause the board of directors to buckle under the pressure and suspend the CPOE system. Years later, it would appear that the relationship between administration and the physicians has not been mended.

B. Kaiser Permanente

This case involves implementing a clinical information system in the Kaiser Permanente healthcare system in Hawaii[5]. Because of the cooperative (non-confrontational) culture in Hawaii and the fact that clinicians are not independent practitioners, but employees of the Kaiser Permanente system, resistance to the system took different forms than is usually experienced.

This case study was prepared as a single document focused on user attitudes to implementation of an EHR. It is represented as a failed implementation of one system, but ultimately resulted in the implementation of another system.

1) Summary of documented facts

In 1999, Kaiser Permanente reviewed two potential EHR systems and selected the second generation Clinical Information System (CIS) (developed jointly by Kaiser Permanente and IBM) over EpicCare. The company planned to implement CIS across all eight of its regions, and began with the Hawaii region, which included 26 primary care teams, 15 clinics and one hospital. The majority of the Hawaiian clinicians were not satisfied with the system choice, but implementation began in their practices in 2001. Clinicians were upset by their lack of participation in the system selection, early identification of problems with the software, and the perception of conflicting goals of clinicians and the organization regarding the system’s performance. By 2003, one third of the Hawaiian sites had already been fully implemented with CIS, while the rest had some read-only functionality available. In Hawaii, the culture is non-confrontational and negative feedback is likely to be interpreted as personal criticism. As a result, clinicians did not provide constructive feedback to leadership, and displayed only minimal active resistance. However, eventually, multiple factors affecting the clinicians, including poor match of system and environment, software problems, decreased productivity, changes in roles and responsibilities and ineffective leadership, created a “counter climate of conflict” in the organization. This resulted in 28 months of ups and downs in the implementation process, after which time, the company finally decided that a more mature version of EpicCare was now a better system choice and CIS would no longer be implemented. All sites would eventually be converted to EpicCare[5].

2) Application of the Model

Because the system being selected was for multiple regions, not just Kaiser Permanente Hawaii, system selection only minimally involved the clinicians from Hawaii. Using the hard tactics associated with legitimate power from the beginning automatically placed the clinicians in a subordinate/superior relationship with the organization leaders. This use of hard tactics from the beginning set the tone for the clinicians’ reactions. Because of the non-confrontational culture in Hawaii and the fact that the clinicians were employees of the organization, the clinicians exhibited passive resistance by not taking action with the leadership about their dissatisfaction with the system choice. When some clinicians did make suggestions for changes to the system, they felt that no one was listening to them. This reinforced their passive resistance by causing them to withdraw from the system even further.

Clinicians also believed that the priorities between the organization and the clinicians were conflicting. The organization was concerned with capturing accurate coding data for proper reimbursement, while the clinicians were interested in usability and flexibility. Passive resistance continued as the clinicians distanced themselves from the system even further by establishing work-arounds in order to get the system to work for them, or shifting some of the work normally done by physicians to nurses or medical assistants. Because they were receiving little or no feedback from the clinicians, organization leadership made no changes in their hard influence tactics.

Active resistance began when the clinicians became more verbal about their problems of decreased productivity, increased time burden, and general problems with the software. Not speaking directly to the local leadership who clinicians believed to be consensus seeking and non-decisive, they resorted to negative background conversation about the system. This tactic is a stealth form of resistance where a person voices opposing opinions that undermine the adversary[27]. As one clinician described it, “I saw very amiable, nice, quiet people starting to talk stink behind the scenes.[5]”

Documentation on this case did not indicate the specific situation that was the breaking point in the implementation process, however it does suggest that organization leadership finally saw problems because of the inability and/or unwillingness (aggressive resistance?) of the clinicians to maintain their pre-CIS level of productivity in the face of system induced costs and inconvenience. It could also be assumed that organization leadership, moving back to soft tactics used reward power by giving the clinicians what they wanted – a better system. In either case, the conflict was resolved with the removal of the CIS system from Kaiser Permanente Hawaii with plans to implement the second choice system, EpicCare.

VI. DISCUSSION

The main difference in the two cases is that physicians were independent practitioners at Cedars-Sinai, but employees at Kaiser Permanente. This resulted in differences in the methods of resistance and in the length of time that it took for that resistance to cause change. Another major difference is that the relationship between the administration and physicians at Cedars-Sinai was permanently damaged while the relationship at Kaiser Permanente did not appear to be. Furst found that employees interpret their manager’s influence tactics in a way that reinforces their existing perceptions of the relationship[28]. If the previous interactions were positive, then administration’s influence tactics will be perceived positively, but if the previous interactions were negative, then future influence tactics will be reacted to suspiciously. This explains why the physicians at Cedars-Sinai are reluctant to attempt CPOE again.

At Cedars-Sinai, the physicians were initially treated as peers by inclusion in the decision process and the pilot, but the implied relationship changed when they did not comply with administration’s mandate that all physicians must be certified in the use of the system. Physicians were immediately treated as subordinates. This follows with Poon et. al.’s findings that hospital leadership realizes that physician resistance is the biggest barrier to overcome when implementing IT and that it believes that this resistance can only be overcome by strong leadership tactics - a specific example of which included empowerment to mandate CPOE use by physicians[8]. As we can see from the Cedars-Sinai example, this type of strong leadership tactic created a barrier to implementation instead of overcoming one. Using our model, it may have been a better tactic to attempt to use referent power (soft tactic) by encouraging physicians that were already certified to enlist the non-certified physicians’ cooperation in obtaining certification.

Judicial use of strong leadership tactics should also defer the use of coercive power when seeking to improve end user performance. A study by Cho on the use of coercive vs. non-coercive power found that using non-coercive types of power will yield positive end user satisfaction and performance, and that use of coercive sources of power negatively affect negative end user satisfaction and performance[29]. Administration’s goal of a single standard of care was a worthy one, but the method to achieve it contributed to the downfall of the system. Those hard tactics served to create and reinforce division of the organization into two adversarial groups – administration vs. physicians. Only a few hundred of the over 2000 physicians resorted to aggressive resistance by boycotting the use of the system, but the remaining physicians, many of whom were satisfied with the system remained apathetic by taking no action in support of the system. Even though the dissatisfied physicians did not actively incorporate the apathetic physicians into their coalition, the downfall for administration was that they did not incorporate them into their coalition either. Whether the majority of the physicians actively supported the dissatisfied physicians or simply remained apathetic to the situation, the end result remained the same.

In the case of Kaiser Permanente, the physicians are employees of the organization and were treated as a separate, subordinate group from the beginning when the organization leadership initiated hard tactics by choosing the system without input from those providing the care. As the implementation continued, the organization leadership did not change their tactics from hard tactics, they merely remained in control with their goal being reimbursement. The main difference in this case is in how the physicians presented their resistance. They did not directly state their concerns to leadership or if they did, they felt they were not heard. This may be a result of the non-confrontational culture as stated by Scott in the study, but it could also be a result of their status as employees rather than peers.

The type of resistance demonstrated by the Kaiser Permanente physicians is similar to the type of resistance demonstrated by nurses (who are almost always employees) when resisting the implementation of IT[30]. This includes work-arounds, extensive criticism of the system, putting off use of the system, but very rarely outright refusal to use the system. The physicians performed all of this behavior, but did not refuse to use the system as the Cedars-Sinai physicians did. This coincides with Poon et. al.’s findings that active resistance to IT is not as common from house staff or hospitalists, who are generally employees of the hospital[8]. The advantage that the Kaiser Permanente physicians have that nurses do not, is that they impact the organization’s revenue when their productivity decreases. This decrease in the number of patients being seen may well have been a factor that caused the organization leadership to become aware that there was a problem. This realization enabled them to back down from hard tactics to soft tactics and remove the CIS system for a better one.

Even when the underlying cause of resistance is a poorly designed system, such as the case at Kaiser Permanente, the health care organization’s investment of time and money behooves them to attempt to save it if at all possible. In such situations, administration must interpret resistance as an indicator that a problem exists. Managers should not perceive resistance as a threat to the power structure of the organization but as a resource for information[31]. Utilizing soft influence tactics has the potential to elicit feedback from resistant clinicians that can enable “system-rescuing” types of changes.

A very recent text of case studies of HIT implementation failures also identifies a few instances of clinician resistance[32]. While in these brief cases, resistance is not explicitly identified as the leading cause of the failure, examination of clinicians’ behavior suggests that potentially significant resistance occurred. Passive resistance is recognized by clinicians’ phoning in verbal orders to avoid the system (Level 2 Resistance) and persistence of former behavior of writing orders on paper (Level 3 Resistance). These actions were major factors in the decline of one system’s CPOE usage from 66% to 15% over time. One clinician, who continued to write orders with a pen stated, “If it fails, it will go away, so I don’t need to learn it.” In another case, clinicians only saw the CPOE system as a reporting tool to administration rather than an aid to improving care. Suggestions provided for resolving these issues follow our model for applying influence. They included involvement of the clinicians in all aspects of the system (planning, selection, implementation, and management) which acknowledges the clinicians’ expertise (Level 2 Influence) and utilization of the clinicians’ influence as champions to obtain co-workers support (Level 3 Influence). Suggestions also included a recommendation to develop a culture that fosters the exchange of information by open communication between administration and clinicians (Level 1 Influence).

Overall, efforts to use soft influence tactics from the beginning, even prior to implementation, may be more effective than waiting until resistance has escalated into an active or aggressive level. Implementers should be alert to passive resistance behavior from the clinicians and initiate or maintain soft influence tactics at that point.

Further application of this model should be conducted on additional examples of information technology implementation and resistance, especially in healthcare. Because only a limited number of cases of CPOE failure from clinician resistance have been documented, using a variety of formats, it is difficult to establish a defined set of criteria for abstracting the facts from these cases. Also, CPOE failures are often written from the perspective of only one viewpoint making it difficult to differentiate fact from perception. Moving forward, application of the model to current implementations may offer better insight than reviewing past cases. Extending the model would include developing a screening tool that would enable healthcare administration to recognize resistive behavior early-on, and provide them with specific soft tactic methods for turning resistance into valuable feedback.

VII. CONCLUSION

Applying the wrong influence tactic at the wrong time can contribute to the failure of a successful system, and negatively affect working relationships for extended periods if not permanently. Guidelines for evaluating the relationship between influence and resistance can be instrumental in preventing this type of disaster. The Ranked Levels of Influence model is such a tool. It can be applied to any type of influence/resistance situation because the associated theories are not specific to any particular context. Because of the volatile power relationship between clinicians and administration, application of this model may be critically useful to healthcare organizations. By using this model as a guideline, an information officer, system developer, or hospital administrator can evaluate the types of resistance being encountered and can select influence tactics that will avert the escalation of resistance to the point that conflict and failure are the result.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by fellowship grant #5 T15 LM007059-20 from the National Library of Medicine. This model was presented in poster form at the American Medical Informatics Association Spring Conference in Phoenix, AZ, May, 2008.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kohen LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington D.C: Institute of Medicine; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.LeapFrogGroup. Announcing the top hospitals 2006 and results of the 2006 Leapfrog hospital survey. 2006 [cited 2006 October 23, 2006]; Available from: http://www.leapfroggroup.org/news/leapfrog_news/3274959.

- 4.Connolly C. The Washington Post. 2005. Mar 21, Doctors cling to pen and paper. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott JT, Rundall TG, Vogt TM, Hsu J. Kaiser Permanente’s experience of implementing an electronic medical record: a qualitative study. BMJ. 2005 December 3;331:1313–16. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38638.497477.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lapointe L, Rivard S. Getting physicians to accept new information technology: insights from case studies. CMAJ. 2006;174(11):1572–78. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stavri PZ, Ash JS. Does failure breed success: narrative analysis of stories about computerized provider order entry. Int J of Med Inform. 2003 Dec;72(1–3):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poon EG, Blumenthal D, Jaggi T, Honour MM, Bates DW, Kaushal R. Overcoming barriers to adopting and implementing computerized physician order entry systems in U.S. hospitals. Health Aff. 2004;23(4):184–90. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raven BH. Social influence and power. In: Steiner JD, Fishbein M, editors. Current studies in social psychology. New York: Holt, Rinehart, Winston; 1965. pp. 371–82. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruins J. Social power and influence tactics: a theoretical introduction. J Soc Issues. 1999;55(1):7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kipnis D, Schmidt SM, Wilkinson I. Intraorganizational influence tactics: explorations in getting one’s way. J Appl Psychol. 1980;65(4):440–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lapointe L, Rivard S. A multilevel model of resistance to information technology implementation. MIS Quart. 2005 September;29(3):461–91. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewin K. The conceptual representation and the measurement of psychological forces. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1938. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coch L, French JR. Overcoming resistance to change. Hum Relat. 1948;1:512–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raven BH, Schwarzwald J, Koslowsky M. Conceptualizing and measuring a power/interaction model of interpersonal influence. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1998;28(4):307–32. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilkes M, Raven BH. Understanding social influence in medical education. Acad Med. 2002 Jun;77(6):481–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200206000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raven BH. The bases of power: origins and recent developments. J of Soc Issues. 1993;49(4):227–51. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raven BH. A power/interaction model of interpersonal influence: French and Raven thirty years later. J Soc Behav Pers. 1992;7(2):217–44. [Google Scholar]

- 19.French JR, Raven BH. The bases of social power. In: Cartwright D, editor. Studies in Social Power. Ann Arbor (MI): Univ. Michigan; 1959. pp. 150–67. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coetsee L. From resistance to commitment. PAQ. 1999 Summer;:204–22. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartos CE. Dissertation. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Dissertation Research Data; 2008. Perceptions of personal power and their relationship to clinician’s resistance to the introduction of computerized physician order entry. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cedars-Sinai. Use of a computerized physician order entry system. 2009 Available from: http://www.csmc.edu/pf_9321.html.

- 24.Langberg ML. Challenges to implementing CPOE: a case study of a work in progress at Cedars-Sinai. Modern Physician [serial on the Internet] 2003 [cited 2009 February 25]; (February 1, 2003): Available from: http://www.accessmylibrary.com/coms2/summary_0286-22602156_ITM.

- 25.Bass A. Health-Care IT: a big rollout bust. CIO Magazine. [serial on the Internet]. 2003 [cited 2009 February 25]; (June 1, 2003): Available from: http://www.cio.com/article/print/28736.

- 26.Morrissey J. Harmonic divergence. Mod Healthc. 2004 February 23;34(8):16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ford JD, Ford LW, McNamara RT. Resistance and the background conversations of change. JOCM. 2002;15(2):105–21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Furst SA, Cable DM. Employee resistance to organizational change: managerial influence tactics and leader-member exchange. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(2):453–62. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cho Y-K, Kendall KE. Management of the information center: the relationship of power to end-user performance and satisfaction. Journal of End User Computing. 1992;4(3):21–30. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Timmons S. Nurses resisting information technology. Nurs Inq. 2003 Dec;10(4):257–69. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1800.2003.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ford JD, Ford LW. Decoding resistance to change. Harv Bus Rev. 2009 April;:99–103. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leviss J, editor. H.I.T. or miss Lessons learned from health information technology implementations. 1. Bethesda, MD: AHIMA Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]