Abstract

Anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) coupled to sulfate reduction (SR) is assumed to be a syntrophic process, in which methanotrophic archaea produce an interspecies electron carrier (IEC), which is subsequently utilized by sulfate-reducing bacteria. In this paper, six methanogenic substrates are tested as candidate-IECs by assessing their effect on AOM and SR by an anaerobic methanotrophic enrichment. The presence of acetate, formate or hydrogen enhanced SR, but did not inhibit AOM, nor did these substrates trigger methanogenesis. Carbon monoxide also enhanced SR but slightly inhibited AOM. Methanol did not enhance SR nor did it inhibit AOM, and methanethiol inhibited both SR and AOM completely. Subsequently, it was calculated at which candidate-IEC concentrations no more Gibbs free energy can be conserved from their production from methane at the applied conditions. These concentrations were at least 1,000 times lower can the final candidate-IEC concentration in the bulk liquid. Therefore, the tested candidate-IECs could not have been produced from methane during the incubations. Hence, acetate, formate, methanol, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen can be excluded as sole IEC in AOM coupled to SR. Methanethiol did inhibit AOM and can therefore not be excluded as IEC by this study.

Keywords: Anaerobic oxidation of methane, Interspecies electron carrier, Methanogenic substrates

Introduction

Anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) coupled to sulfate reduction (SR) according to Eq. 1, is an important process in the global carbon cycle (Hinrichs and Boetius 2002). The process was discovered during geochemical studies in marine sediments (Martens and Berner 1974; Barnes and Goldberg 1976; Reeburgh 1976).

|

1 |

Phylogenetic analysis of AOM-SR sediments identified three novel groups of archaea putative called anaerobic methanotrophs (ANME); ANME-1, ANME-2, and ANME-3. These ANME are distantly related to cultivated methanogenic members from the orders Methanosarcinales and Methanomicrobiales (Hinrichs et al. 1999; Orphan et al. 2002; Knittel et al. 2005; Niemann et al. 2006). Orphan et al. (2001, 2002) showed that cells belonging to ANME-1 and ANME-2 assimilated carbon from methane (CH4) during AOM. ANME probably mediate a form of reversed methanogenesis since AOM, like methanogenesis, is inhibited by bromoethanesulfonate (Nauhaus et al. 2005); an analogue of the methyl-coenzyme M reductase was found to make up 7% of the extracted soluble proteins from an AOM-mediating microbial mat from the Black Sea (Krüger et al. 2003), and ANME-1 cells were found to contain most of the genes typically associated with CH4 production (Hallam et al. 2003, 2004; Meyerdierks et al. 2010). Moreover, methanogens (Zehnder and Brock 1980; Harder 1997; Moran et al. 2007) and methanogenic sludge (Meulepas et al. 2010) also mediate CH4 oxidation, however during net methanogenesis.

No gene analogues for enzymes involved in dissimilatory SR were found in archaea belonging to ANME groups (Thauer and Shima 2008; Meyerdierks et al. 2010) and FISH techniques showed that ANME occur in aggregates (Boetius et al. 2000; Michaelis et al. 2002; Knittel et al. 2005) with bacteria related to Desulfosarcina–Desulfococcus or Desulfobulbus. These findings suggest that AOM coupled to SR is a syntrophic process, in which ANME convert CH4 to a metabolite which forms the electron donor for the sulfate-reducing bacterial (SRB) partner.

Given the evidence for reversed methanogenesis, methanogenic substrates have been proposed to act as interspecies electron carrier (IEC) (Hoehler et al. 1994; DeLong 2000). The standard Gibbs free energy change at pH 7 (∆G°’) of the production of these IECs from CH4 is positive (Table 1), but when the IEC concentration is kept low enough by the sulfate-reducing partner, the Gibbs free energy change will be negative. However, the SR activity of Hydrate Ridge sediment with hydrogen, formate, acetate, methanol, carbon monoxide, and methylamines was lower than SR activity on CH4, indicating that SRB involved in AOM, were not adapted to these substrates (Nauhaus et al. 2002, 2005). Wegener (2008) showed that the bacterial partners mainly assimilated inorganic carbon, which makes the uptake of an organic IEC less likely. Sørensen et al. (2001) excluded hydrogen, acetate, and methanol as IEC because the maximum diffusion distances of those compounds at in situ concentrations and rates were smaller than the thickness of two prokaryotic cell walls. Orcutt and Meile (2008) showed with process-based modeling that hydrogen and formate could not be exchanged fast enough between syntrophic partners to sustain the sulfate reduction rates found by Nauhaus et al. (2007), but for acetate this might be possible. Using a spherical diffusion-reaction model Alperin and Hoehler (2009) concluded that hydrogen, formate, and acetate are thermodynamically and physically possible intermediates in AOM coupled to SR.

Table 1.

The production and consumption of candidate interspecies electron carriers (IECs) in AOM coupled to SR

| Candidate-IEC | Potential subconversions in AOM coupled to SR | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | CH4 + HCO−3 → CH3COO− + H2O | ∆Gº’IEC production | +31 kJ mol−1 CH4 |

| CH3COO− + SO2-4 → HS− + 2HCO−3 | ∆Gº’IEC consumption | −47 kJ mol−1 SO2-4 | |

| Formate | CH4 + 3HCO−3 → 4HCO−2 + H+ + H2O | ∆Gº’IEC production | +128 kJ mol−1 CH4 |

| 4HCO−2 + SO2−4 + H+ → HS− + 4HCO−3 | ∆Gº’IEC consumption | −144 kJ mol−1 SO2−4 | |

| Methanol | CH4 + 1/3HCO−3 + 1/3H+ + 1/3H2O → 4/3CH3OH | ∆Gº’IEC production | +104 kJ mol−1 CH4 |

| 4/3CH3OH + SO2−4 → HS− + 4/3HCO−3 + 1/3H+ + 4/3H2O | ∆Gº’IEC consumption | −120 kJ mol−1 SO2−4 | |

| Carbon monoxide | CH4 + 3HCO−3 + 3H+ → 4CO + 5H2O | ∆Gº’IEC production | +196 kJ mol−1 CH4 |

| 4CO + SO2−4 + 4H2O → HS− + 4HCO−3 + 3H+ | ∆Gº’IEC consumption | −212 kJ mol−1 SO2-4 | |

| Methanethiol | CH4 + 1/3HCO−3 + 5/3H+ + 4/3HS− → 4/3H3CSH + H2O | ∆Gº’IEC production | +55 kJ mol−1 CH4 |

| 4/3H3CSH + SO2−4 → 7/3HS− + 4/3HCO−3 + 5/3H+ | ∆Gº’IEC consumption | −71 kJ mol−1 SO2-4 | |

| Hydrogen | CH4 + 3H2O → 4H2 + HCO−3 + H+ | ∆Gº’IEC production | +136 kJ mol−1 CH4 |

| 4H2 + SO−4 + H+ → HS− + 4H2O | ∆Gº’IEC consumption | −152 kJ mol−1 SO2-4 | |

The standard Gibbs free energy changes were obtained from Thauer et al. (1977)

This study presents a novel approach to investigate whether a compound acts as IEC. Firstly, the effect of the presence of candidate-IECs, at relative high concentrations, on AOM and SR by an enrichment, of ANME-2a and bacteria mainly belonging to Deltaproteobacteria and Flavobacteriales (Meulepas et al. 2009; Jagersma et al. 2009), is assessed. And secondly, the concentration of each candidate-IEC is calculated at which no more energy can be obtained from their production from CH4. If AOM still occurs at IEC concentrations far above this theoretical maximum, the AOM does not proceed via the production of that particular IEC. Due to the high AOM and SR activity of the enrichment (0.2 mmol L−1 day−1), the effect of these additives can be assessed within a period of 4 days.

Material and methods

Inoculate

The biomass used for this research was taken from a 1-L submersed-membrane bioreactor, inoculated with 10 g dry weight Eckernförde Bay sediment (Baltic Sea), operated at 15 °C, sparged with 4.8 L L−1 day−1 pure CH4 gas and fed with 0.14 L L−1 day−1 marine medium. The basal medium consisted of: NaCl (19.8 g L−1), KCl (0.45 g L−1), MgCl2·6H20 (4.25 g L−1), NH4Cl (0.25 g L−1), CaCl2·2H2O (1.19 g L−1), MgSO4·7H2O (5.10 g L−1), KH2PO4 (0.34 g L−1), K2HPO4·3H2O (1.25 g L−1), a trace element solution (1 mL L−1), a vitamin solution (1 mL L−1), a 0.5 g L−1 resazurin solution (1 mL L−1), a 0.1 M Na2S solution (1 mL L−1), and demineralized water. The trace elements and vitamin solutions were made according to Widdel and Bak (1992). The first 330 days, 70 µmol L−1 day−1 acetate was supplied as cosubstrate, after that CH4 was the sole supplied electron donor and carbon source. During 884 days, the volumetric AOM rate increased exponentially from 0.002 to 0.6 mmol L−1 day−1 (Meulepas et al. 2009). The biomass used for this research was sampled at day 584. To ensure homogeneous sampling, liquid recirculation (0.5 L min−1) and gas sparging (2 L min−1) were applied prior to and during sampling. Microbial analyses of the enrichment (clone library and fluorescent in situ hybridization) showed that the archaeal community was dominated by ANME-2a and that the bacterial community mainly consists of members of the Deltaproteobacteria and Bacteroidetes (Jagersma et al. 2009). During AOM, carbon derived from CH4 was incorporated in both archaeal and bacterial lipids (Jagersma et al. 2009).

Incubations with candidate-IECs

Experiments were done in 35-mL serum bottles closed with butyl rubber stoppers and caps. After determining the exact weight and volume, the bottles were eluted with nitrogen gas. Subsequently, 30 mL undiluted reactor suspension was transferred from the bioreactor to the bottles by syringe. The reactor suspension contained 0.59 g volatile suspended solids per liter (a measure for the biomass content). The headspace of each bottle was evacuated again and replaced by 0.16 (±0.01) MPa 13C-labeled CH4 (13CH4) with a purity of 99% from Campro (Veenendaal, The Netherlands). Subsequently, 1.0 mM acetate, 1.0 mM formate, 1.0 mM methanol, 7.2 kPa carbon monoxide, 1.0 mM methanethiol, or 7.2 kPa hydrogen were added as candidate-IECs from stock bottles. In addition, control incubations without IEC were done. Incubations were done in duplicate. However, one incubation with methanethiol and one with hydrogen had to be terminated before day 4, due to leaking. These duplicates could not be repeated due to a limited biomass stock. The bottles were incubated at 15 °C and shaken in an orbital shaker at 100 rpm. The gas composition, pH, and pressure were determined once or twice a day. The carbon monoxide and hydrogen fraction in the headspace, the sulfate and formate concentration, the dissolved sulfide concentration, and the concentration of fatty acids and alcohols were analyzed immediately after inoculation and after 4 days. Sampling was done at the incubation temperature (15 °C).

Analysis

The headspace composition was measured on a gas chromatograph–mass spectrometer (GC-MS) from Interscience (Breda, The Netherlands). The system was composed of a Trace GC equipped with a GS-GasPro column (30 m by 0.32 mm; J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA, USA), and a Ion-Trap MS. Helium was the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.7 mL min−1. The column temperature was 30 °C. The fractions of CH4 and CO2 in the headspace were derived from the peak areas in the gas chromatograph. The fractions of 13C-labeled CH4 (13CH4) and 13C-labeled CO2 (13CO2) were derived from the mass spectra as done by Shigematsu et al. (2004). The headspace pressure, sulfide concentration, and pH were analyzed as described by Meulepas et al. (2009). The sulfate concentration was analyzed according to Sipma et al. (2004), and the acetate and methanol concentration were analyzed according to Weijma et al. (2000). Formate was measured on a DX-600 IC system (Dionex Corporation, Salt Lake City, USA) equipped with IonPac AG17 and AS17 4 mm columns, operated at a temperature of 30 °C, and a flow rate of 1.5 mL min−1. The injection volume was 25 μL. The eluent was made on-line using the EG40 Eluent Generator (Dionex) equipped with a KOH cartridge (Dionex P/N 053921) and deionized water as the carrier. Prior to analysis, samples were centrifuged and diluted 20 times. Hydrogen and carbon monoxide were measured on a gas chromatograph HP 5890 (Hewlett Packard, Palo Alto, USA) as described previously (Sipma et al. 2004). Methanethiol was measured on a HP 6890 gas chromatograph equipped with a Supelco sulfur SPB-1 column (Bellefonte, PA, USA) according to van den Bosch et al. (2009).

Calculations

The 13C-dissolved inorganic carbon (13C-DIC, 13C-labeled CO2, and 13C-labeled bicarbonate) and 12C-DIC per bottle were calculated according to the equation given by Meulepas et al. (2009).

The concentration of each candidate-IEC at which no more energy can be obtained (∆G IEC production = 0) from their production from CH4 (Table 1) was calculated. This is done according to Eq. 2.

|

2 |

- R

gas constant = 8.314 J mol−1 K−1

- T

temperature in K = 288.15 K

Results

Incubations

The 13C-DIC production is taken as a measure for 13CH4 oxidation because the percentage 13C in DIC produced from other (not 13C-enriched) sources is only around 1.1%, while the 12C-DIC production (Fig. 2a) did not even exceed the 13C-DIC production (Fig. 1) in any of the incubations. The sulfide production was taken as a measure for SR, which was in all incubations coupled to the sulfate removal (Fig. 2b).

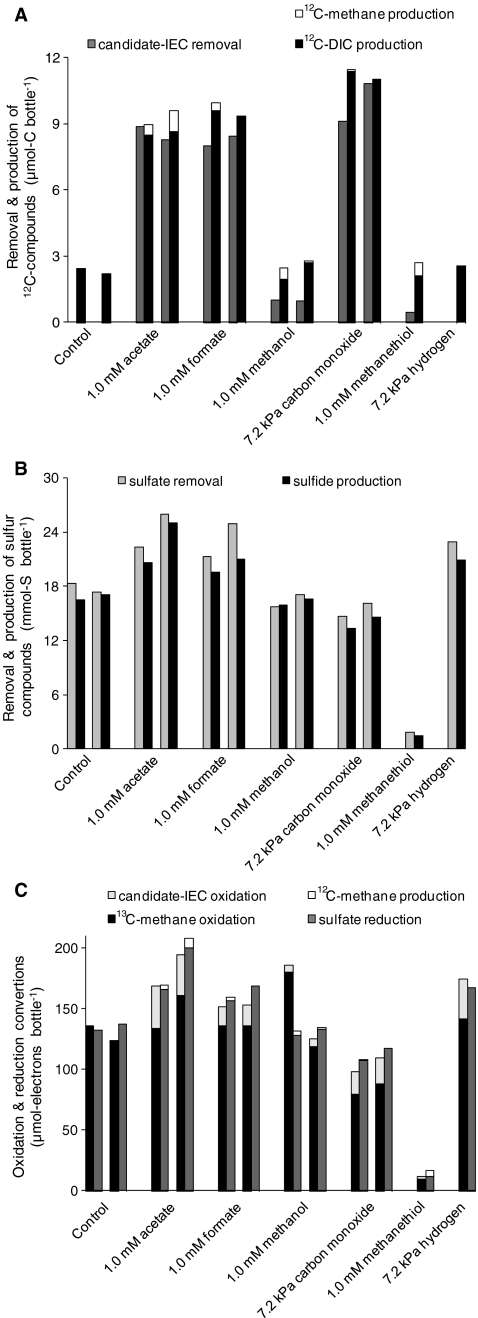

Fig. 2.

a 12Carbon, b sulfur, and c reduction equivalent balances over 4-day batch incubations in the absence (control) or in the presence of one candidate-IEC. The 35-mL bottles contained 30 mL biomass suspension from the enrichment bioreactor and initially 0.16 (±0.01) MPa 13CH4, 15 (±1) mM sulfate, and 0.2 (±0.1) mM sulfide

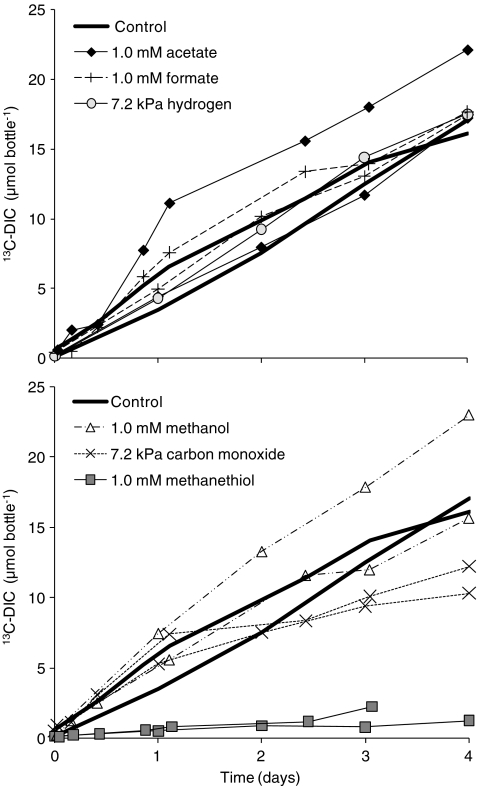

Fig. 1.

13C-DIC production in time, during 4-day batch incubations, in the absence (control) or in the presence of one candidate-IEC. The bottles contained 30 mL biomass suspension from the enrichment bioreactor and initially 0.16 (±0.01) MPa 13CH4, 15 (±1) mM sulfate and 0.2 (±0.1) mM sulfide

In the absence of candidate-IECs (controls), there was a linear accumulation of 13C-DIC during the 4-day incubation (Fig. 1); this 13CH4 oxidation was coupled to SR (Fig. 2c), according to the stoichiometry of Eq. 1.

In the presence of acetate, formate, methanol, or hydrogen, there was also a linear accumulation of 13C-DIC (Fig. 1), the rates (3.9–5.7 µmol bottle−1 day−1) were comparable with the rates without a candidate-IEC (3.9 and 4.2 µmol bottle−1 day−1). In the incubations with carbon monoxide, the 13C-DIC production rate was slightly lower (2.7 and 3.0 µmol bottle−1 day−1) and methanethiol completely inhibited 13C-DIC production.

Some acetate (8.8 and 8.3 µmol-C), formate (8.0 and 8.4 µmol-C), and carbon monoxide (9.1 and 10.8 µmol-C) were being removed during the 4-day incubation. Figure 2a shows that the removal of these candidate-IECs was coupled to 12C-DIC production and not 12CH4 production, indicating complete oxidation. Methanol (1.0 and 1.0 µmol-C bottle−1) and methanethiol (0.4 µmol-C bottle−1) were hardly removed. All incubations showed some (up to 2.6 µmol bottle−1) background 12C-DIC production, likely released from the inoculate.

Figure 2c compares oxidation conversions with reduction conversions. In the presence of acetate, formate, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen more sulfate was reduced than 13CH4 oxidized. This additional SR was coupled to the oxidation of candidate-IECs. Therefore, CH4, acetate, formate, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen were all used as electron donor for SR by the enrichment, although the oxidation of 13CH4 was, in all incubations, dominant over the oxidation of candidate-IECs. Both SR and 13CH4 oxidation were inhibited by the presence of methanethiol.

Thermodynamic calculations

Table 2 presents the concentrations of candidate-IECs at which their production, under the applied experimental conditions, is no longer thermodynamically possible. To obtain maximum concentrations, the highest measured CH4 partial pressure (0.16 MPa), HS− concentration (1 mM) and HCO−3 concentrations (1 mM) were used for the calculations. Only for the calculation of the maximum H2 partial pressure, the lowest HCO−3 concentration (0.2 mM) was used. The theoretical maximum concentration for the production of each candidate-IEC was always at least 1,000 times lower than the actual concentration measured at the end of the experiment.

Table 2.

The concentration of candidate interspecies electron carriers (IECs) at which their production from CH4 is no longer thermodynamically possible (ΔG’ = 0) at 0.16 MPa CH4, 0.2 mM HCO−3 (for H2) or 1 mM HCO−3 (of the other potential-IECs), 1 mM HS−, 30 °C, and a pH of 7

| IEC | IEC concentration at which ∆G IEC production = 0 | IEC concentration on day 4 |

|---|---|---|

| Acetate | 3.8 × 10−9 M | 8.5 × 10−4, 8.6 × 10−4 M |

| Formate | 1.0 × 10−8 M | 7.3 × 10−4, 7.2 × 10−4 M |

| Methanol | 1.8 × 10−15 M | 9.3 × 10−4, 9.3 × 10−4 M |

| Carbon monoxide | 8.4 × 10−10 kPa | 4.9, 4.4 kPa |

| Methanethiol | 8.4 × 10−12 M | 9.9 × 10−4 M |

| Hydrogen | 6.6 × 10−4 kPa | 3.2 kPa |

Discussion

Exclusion of candidate-IECs

This research shows that acetate, formate, methanol, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen can be excluded as sole IEC in AOM coupled to SR by an enrichment composed of ANME-2a and bacteria mainly belonging to Deltaproteobacteria and Flavobacteriales. The 13CH4 oxidation rates in the presence of these compounds were not or hardly lower than in the controls (Fig. 1). Moreover, during the 4-day incubations, the concentrations of these candidate-IECs were at least 1,000× higher than the candidate-IEC concentrations at which no more Gibbs free energy can be conserved from their production from CH4 at the applied conditions (Table 2). Nauhaus et al. (2002, 2005) already showed that acetate, formate, methanol, carbon monoxide, methylamines, and hydrogen are unlikely IECs in AOM coupled to SR by the ANME-2/bacteria community in Hydrate Ridge sediment because the SR activity on those compounds was lower than on CH4. In Black Sea microbial mats, the SR activity with acetate was also lower than with methane, but with hydrogen and formate this was not the case, which was likely due to the rapid enrichment of SRB not involved in AOM (Nauhaus et al. 2005). Possibly the carbon monoxide concentration (10 kPa CO) used by Nauhaus et al. (2005) was inhibitory for sulfate reduction or the candidate-IECs were consumed by methanogens or homoacetogens. By also assessing the 13CH4 oxidation rate (Fig. 1), the 12CH4 production (Fig. 2a), 12C-DIC production (Fig. 2a), and the candidate-IEC consumption (Fig. 2a and c), those possibilities can be excluded in this study for acetate, formate, methanol, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen.

Inhibition by carbon monoxide and methanethiol

13CH4 oxidation was slightly hampered by carbon monoxide and completely inhibited by methanethiol (Fig. 1), both compounds have been reported to be toxic. Carbon monoxide hampered SR by sulfate-reducing sludge at a concentration of 5% or higher (van Houten et al. 1995), and sulfate reducers used only methyl sulfides as substrate at low concentrations (<10 µM; Kiene et al. 1986). If these compounds would be produced in situ, the concentrations would remain much lower due to simultaneous consumption, therefore toxic effects would be less profound. Because methanethiol inhibited AOM, it can therefore not be excluded as IEC in AOM coupled to SR. Moran et al. (2007) also reported an inhibition of AOM by methanethiol. If electrons would be transferred via methanethiol, sulfate reducers would be able to utilize these compounds; however that did not occur (Fig. 2b). Possibly, the sulfate reducers were intoxicated by methanethiol.

Local concentration of candidate-IECs

Many of the candidate-IECs tested were consumed (Fig. 2a, c), which can result in a concentration gradient within the biomass flocks. Therefore, the concentration near the responsible organism can be lower than in the bulk liquid. A big difference between the concentration in the bulk liquid at the concentration near the organism mediating AOM is not expected though because the reactor suspension was well mixed (orbital shaker at 100 rpm), the biomass flocks were small (0.1 mm; Meulepas et al. 2009), and the candidate-IEC consumption rates were low (<4 µmol bottle−1 day−1).

Syntrophy between ANME and SRB

The reason that the addition of a candidate-IEC does not affect AOM and SR might be the involvement of more than one intermediate in AOM coupled to SR (Valentine and Reeburgh 2000; Stams and Plugge 2009). Other theories for the shuttling of electrons between ANME and SRB are that reduction equivalents are transferred via extracellular redox shuttles (Widdel and Rabus 2001; Wegener et al. 2008) or via membrane-bound redox shuttles or so-called “nanowires” (Reguera et al. 2005; Stams et al. 2006; Stams and Plugge 2009; Thauer and Shima 2008; Wegener et al. 2008). The extracellular redox shuttle theory requires the shuttle to be transported back to the ANME after donating the electrons to the SRB, giving rise to an additional loss in Gibbs free energy change available for the microorganisms, due to the concentration gradients between the syntrophic partners. The membrane-bound redox shuttles require the ANME and SRB to make direct physical contact, which is not always the case (Michaelis et al. 2002; Knittel et al. 2005; Orphan et al. 2002; Treude et al. 2005; Jagersma et al. 2009). However, Nielsen et al. (2010) showed that electrical currents in marine sediments coupled spatially separated biogeochemical processes, presumably trough nanowires. Such mechanism might also be responsible for interspecies electron transfer in AOM coupled to SR.

At in situ conditions there is only −22.35 kJ mol−1 available for AOM coupled to SR (Harder 1997). Methanogenic archaea and sulfate-reducing bacteria have been shown to require a free energy change under physiological conditions of at least −10 and −19 kJ mol−1, respectively, to support their metabolism in situ (Hoehler et al. 2001; Dale et al. 2006). Therefore, the in situ free energy change of AOM coupled to SR is probably not sufficiently large to fuel the energy metabolism of two microorganisms in tandem (Schink 1997; Thauer and Shima 2008). Further research should also consider the possibility that one microorganism is responsible for AOM coupled to SR.

Alternative electron donors

The enrichment was able to utilize acetate, formate, methanol, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen as electron donor for SR (Fig. 2c), although the enrichment was not fed with any other electron donor and carbon source than CH4 for 512 days (Meulepas et al. 2009). Prior to this, the enrichment was additionally fed with small amounts of acetate (70 µmol L−1 day−1) for a period of 330 days. Possibly, the sulfate reducers involved in AOM coupled to SR are capable of utilizing acetate, formate, methanol, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen as alternative electron donors for the IEC or CH4. If this would be the case, those microorganisms could be enriched on those alternative substrates instead of on CH4. Another explanation is that other SRB, not involved in AOM coupled to SR, survived the enrichment period. This hypothesis would require inactive SRB to become active within the 4-day duration of the experiment, which is a rather short time span.

Acknowledgments

This work was part the Anaerobic Methane Oxidation for Sulfate Reduction project supported by the Dutch ministries of Economical affairs, Education, culture and science, and Environment and special planning as part their EET program and was cofunded by King Abdullah University of Science and Technology through the SOWACOR project.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Alperin MJ, Hoehler TM. Anaerobic methane oxidation by archaea/sulfate-reducing bacteria aggregates: 1. Thermodynamic and physical constraints. Am J Sci. 2009;309:869–957. doi: 10.2475/10.2009.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes R, Goldberg E. Methane production and consumption in anoxic marine sediments. Geology. 1976;4:297–300. doi: 10.1130/0091-7613(1976)4<297:MPACIA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boetius A, Ravenschlag K, Schubert CJ, Rickert D, Widdel F, Gieseke A, Amann R, Jørgensen BB, Witte U, Pfannkuche O. A marine microbial consortium apparently mediating anaerobic oxidation of methane. Nature. 2000;407:623–626. doi: 10.1038/35036572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AW, Regnier P, van Cappellen P. Bioenergetic controls on anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) in coastal marine sediments: a theoretical analysis. Am J Sci. 2006;306:246–294. doi: 10.2475/ajs.306.4.246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong EF. Resolving a methane mystery. Nature. 2000;407:577–579. doi: 10.1038/35036677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallam SJ, Girguis PR, Preston CM, Richardson PM, DeLong EF. Metabolism of reduced methylated sulfur compounds in anaerobic sediments and by a pure culture of an estuarine methanogen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:1037–1045. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.5.1037-1045.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallam SJ, Putnam N, Preston CM, Detter JC, Rokhsar D, Richardson PM, DeLong EF. Reverse methanogenesis: testing the hypothesis with environmental genomics. Science. 2004;305:1457–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.1100025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder J. Anaerobic methane oxidation by bacteria employing 14C-methane uncontaminated with 14C-carbon monoxide. Mar Geol. 1997;137:13–23. doi: 10.1016/S0025-3227(96)00075-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs K-U, Boetius A (2002) The anaerobic oxidation of methane: new insights in microbial ecology and biogeochemistry. In: Ocean Margin Systems. Wefer G, Billet D, Hebbeln D, Jørgensen BB, Schlüter M, van Weering T (eds). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag, pp. 457–477

- Hinrichs K-U, Hayes JM, Sylva SP, Brewer PG, DeLong EF. Methane-consuming archaebacteria in marine sediments. Nature. 1986;398:802–805. doi: 10.1038/19751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs K-U, Summons RE, Orphan V, Sylva SP, Hayes JM. Molecular and isotopic analyses of anaerobic methane-oxidizing communities in marine sediments. Org Geochem. 2000;31:1685–1701. doi: 10.1016/S0146-6380(00)00106-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehler TM, Alperin MJ, Albert DB, Martens CS. Field and laboratory studies of methane oxidation in an anoxic marine sediment: evidence for a methanogen-sulfate reducer consortium. Glob Biogeochem Cycles. 1994;8:451–463. doi: 10.1029/94GB01800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehler TM, Alperin MJ, Albert DB, Martens CS. Apparent minimum free energy requirements for methanogenic Archaea and sulfate-reducing bacteria in an anoxic marine sediment. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2001;38:33–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2001.tb00879.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jagersma CG, Meulepas RJW, Heikamp-de Jong I, Gieteling J, Klimiuk A, Schouten S, Sinninghe Damsté JS, Lens PNL, Stams AJM. Microbial diversity and community structure of a highly active anaerobic methane oxidizing sulfate-reducing enrichment. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:3223–3232. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiene RP, Oremland RS, Catena A, Miller LG, Capone DG. Metabolism of reduced methylated sulfur compounds in anaerobic sediments and by a pure culture of an estuarine methanogen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:1037–1045. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.5.1037-1045.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knittel K, Lösekann T, Boetius A, Kort R, Amann R. Diversity and distribution of methanotrophic archaea at cold seeps. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:467–479. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.1.467-479.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger M, Meyerdierks A, Glöckner FO, Amann R, Widdel F, Kube M, Reinhardt R, Kahnt J, Böcher R, Thauer RK, Shima S. A conspicuous nickel protein in microbial mats that oxidize methane anaerobically. Nature. 2003;426:878–881. doi: 10.1038/nature02207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens CS, Berner RA. Methane production in the interstitial waters of sulfate-depleted marine sediments. Science. 1974;185:1167–1169. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4157.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulepas RJW, Jagersma CG, Gieteling J, Buisman CJN, Stams AJM, Lens PNL. Enrichment of anaerobic methanotrophs in a sulfate-reducing membrane bioreactor. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;104(3):458–470. doi: 10.1002/bit.22412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulepas RJW, Jagersma CG, Zhang Y, Petrillo M, Cai H, Buisman CJN, Stams AJM, Lens PNL. Trace methane oxidation and the methane-dependency of sulfate reduction in anaerobic granular sludge. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2010;72:261–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerdierks A, Kube M, Kostadinov I, Teeling H, Glöckner FO, Reinhardt R, Amann R. Metagenome and mRNA expression analyses of anaerobic methanotrophic archaea of the ANME-1 group. Environ Microbiol. 2010;12:422–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis W, Seifert R, Nauhaus K, Treude T, Thiel V, Blumenberg M, Knittel K, Gieseke A, Peterknecht K, Pape T, Boetius A, Amann R, Jørgensen BB, Widdel F, Peckmann J, Pimenov NV, Gulin MB. Microbial reefs in the Black sea fueled by anaerobic oxidation of methane. Science. 2002;297:1014–1015. doi: 10.1126/science.1072502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran JJ, Beal EJ, Vrentas JM, Orphan VJ, Freeman KH, House CH. Methyl sulfides as intermediates in the anaerobic oxidation of methane. Environ Microbiol. 2007;10:162–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauhaus K, Boetius A, Krüger M, Widdel F. In vitro demonstration of anaerobic oxidation of methane coupled to sulphate reduction in sediment from a marine gas hydrate area. Environ Microbiol. 2002;4:296–230. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauhaus K, Treude T, Boetius A, Krüger M. Environmental regulation of the anaerobic oxidation of methane: a comparison of ANME-1 and ANME-2 communities. Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:98–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naushaus K, Albreacht M, Elvert M, Boetius A, Widdel F. In vitro cell growth of marine archaeal-bacterial consortia during anaerobic oxidation of methane with sulfate. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9(1):187–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen LP, Risgaard-Petersen N, Fossing H, Christensen PB, Sayama M. Electric currents couple spatially separated biogeochemical processes in marine sediment. Nature. 2010;463:1071–1074. doi: 10.1038/nature08790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemann H, Lõsekann T, de Beer D, Elvert M, Nadalig T, Knittel K, Amann R, Sauter EJ, Schlüter M, Klages M, Foucher JP, Boetius A. Novel microbial communities of the Haakon Mosby mud volcano and their role as a methane sink. Nature. 2006;443:854–858. doi: 10.1038/nature05227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orcutt B, Meile C. Constraints on mechanisms and rates of anaerobic oxidation of methane by microbial consortia: process-based modeling of ANME-2 archaea and sulfate-reducing bacteria interactions. Biogeosciences Discuss. 2008;5:1933–1967. doi: 10.5194/bgd-5-1933-2008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orphan VJ, House CH, Hinrichs K-U, McKeegan KD, DeLong EF. Methane-consuming archaea revealed by directly coupled isotopic and phylogenetic analysis. Science. 2001;293:484–487. doi: 10.1126/science.1061338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orphan VJ, House CH, Hinrichs K-U, McKeegan KD, DeLong EF. Multiple archaeal groups mediate methane oxidation in anoxic cold seep sediments. PNAS. 2002;99:7663–7668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072210299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeburgh WS. Methane consumption in Cariaco Trench waters and sediments. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1976;28:337–344. doi: 10.1016/0012-821X(76)90195-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reguera G, McCarthy KD, Metha T, Nicoll JS, Tuominen MT, Lovley DR. Extracellular electron transfer via microbial nanowires. Nature. 2005;435:1098–1101. doi: 10.1038/nature03661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schink B. Energetics of syntrophic cooperation in methanogenic degradation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:262–280. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.2.262-280.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigematsu T, Tang Y, Kobayashi T, Kawaguchi H, Morimura S, Kida K (2004) Effect of dilution rate on metabolic pathway shift between aceticlastic and nonaceticlastic methanogenesis in chemostat cultivation. Appl Environ Microbiol 70(7):4048–4052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sipma J, Meulepas RJW, Parshina SN, Stams AJM, Lettinga G, Lens PNL. Effect of carbon monoxide, hydrogen and sulfate on thermophilic (55 °C) hydrogenogenic carbon monoxide conversion in two anaerobic bioreactor sludges. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2004;64(3):421–428. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen KB, Finster K, Ramsing NB. Thermodynamic and kinetic requirements in anaerobic methane oxidizing consortia exclude hydrogen, acetate, and methanol as possible electron shuttles. Microb Ecol. 2001;42:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s002480000083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stams AJM, Plugge CM. Electron transfer in syntrophic communities of anaerobic bacteria and archaea. Nature Microbiol. Rev. 2009;7:568–577. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stams AJM, de Bok FA, Plugge CM, van Eekert MH, Dolfing J, Schraa G. Exocellular electron transfer in anaerobic microbial communities. Environ Microbiol. 2006;8:371–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thauer RK, Shima S. Methane as fuel for anaerobic organisms. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1125:158–170. doi: 10.1196/annals.1419.000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thauer RK, Jungermann K, Decker K. Energy conservation in chemotrophic anaerobic bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1977;41:100–180. doi: 10.1128/br.41.1.100-180.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treude T, Krüger M, Boetius A, Jørgensen BB. Environmental control on anaerobic oxidation of methane in the gassy sediments of Eckernförde Bay (German Baltic) Limnol Oceanogr. 2005;50:1771–1786. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine DL, Reeburgh WS. New perspectives on anaerobic methane oxidation. Environ Microbiol. 2000;2:477–484. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bosch PLF, Fortuny-Picornell M, Janssen AJH. Effects of methanethiol on the biological oxidation of sulfide at natron-alkaline conditions. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:453–459. doi: 10.1021/es801894p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Houten RT, van der Spoel H, van Aelst AC, Hulshoff Pol LW, Lettinga G. Biological sulfate reduction using synthesis gas as energy and carbon source. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1995;50:136–144. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19960420)50:2<136::AID-BIT3>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener G, Niemann H, Elvert M, Hinrichs K-U, Boetius A. Assimilation of methane and inorganic carbon by microbial communities mediating the anaerobic oxidation of methane. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:2287–2298. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weijma J, Stams AJM, Hulshoff Pol LW, Lettinga G. Thermophilic sulfate reduction and methanogenesis with methanol in a high rate anaerobic reactor. Biotechnol Bioenring. 2000;67(3):354–363. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(20000205)67:3<354::AID-BIT12>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdel F, Bak F. Gram negative mesophilic sulphate-reducing bacteria. In: Balows A, Trüper HG, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K-H, editors. The prokaryotes. New York: Springer; 1992. pp. 3352–3378. [Google Scholar]

- Widdel F, Rabus R. Anaerobic biodegradation of saturated and aromatic hydrocarbons. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2001;12:259–276. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehnder AJB, Brock TD. Anaerobic methane oxidation: occurrence and ecology. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;39:194–204. doi: 10.1128/aem.39.1.194-204.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]