Abstract

Initiation of renal atherosclerosis occurs primarily at the caudal region of the renal artery ostium. To date, no mechanism for initiation of atherosclerosis at this site has been substantiated. Herein, we identify a renal artery flow diverter on the caudal wall of the renal artery ostium that directs flow into the renal artery and selectively retains LDL, an initial step in atherosclerosis. High resolution ultrasound revealed the generation of flow eddies by the caudal diverter in vivo, consistent with a role in directing aortic flow to the renal artery. Two photon excitation en face microscopy of the diverter revealed a substantial reduction in the elastic lamina exposing potential retention sites for LDL. Fluorescent LDL was selectively retained by the renal artery diverter, consistent with its molecular structure. We propose that the rigid macromolecular structure of the renal artery ostium diverter is required for its vascular function and contributes to the initiation of renal atherosclerosis by the retention of LDL.

Keywords: renal artery ostium, collagen, elastin, LDL retention, two photon microscopy, Doppler ultrasound, atherosclerosis

1. Introduction

Atherosclerosis of the renal artery can lead to stenosis, progressive renal dysfunction and end-stage renal failure [1]. Atherosclerotic lesions in the renal artery usually originate at the renal ostium, often as a result of progression of lesions at the aortic entrance into the ostium [2,3]. Studies of both human [4,5] and animal [6,7] aortas have established that these lesions initiate on the caudal side of the aortic entrance to the renal artery. Little is currently known about the determinants of increased atherosclerosis observed at this site.

Atherosclerotic lesions initiate as a result of the deposition of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and related lipoproteins in the extracellular matrix of the intimal and medial layers of the arterial wall [8,9]. LDL retention in extracellular matrix at the renal ostium and other locations in the arterial wall begins during human fetal development [10]. LDL deposition continues throughout life resulting in an increase in the arterial wall lipid burden with time [8,9,11,12]. Atherosclerotic lesions are thought to arise as a result of a maladaptive response by macrophages and other immunosurveillance cells to the presence of lipid retained in the extracellular matrix [8].

The apoB-100 protein component of LDL has been shown to possess a sequence that is responsible for its binding to the proteoglycan component of extracellular matrix [13–15]. Recently, Kwon et al. (2008) showed that increased LDL retention occurs in collagen/proteoglycan-enriched atherosclerosis-susceptible arterial branch points that lack an elastin barrier[16]. In the present study, we evaluated renal ostial macromolecular structure and LDL binding to better understand the relationship of arterial wall structure to atherogenic susceptibility in this clinically-relevant site of atherosclerosis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Porcine aorta and renal artery preparation

Aorta samples, with left and right renal arteries attached, were harvested from anesthesized and heparinized (10,000 U IV) 16- to 32-week-old pigs. Samples were immediately placed in cold normal saline. After dissection of the renal arteries from the aorta, a 1-cm portion of the aorta surrounding the renal ostia was cut longitudinally. The left and right renal ostia were separated and dissected into 1-cm2 pieces. Renal artery samples were cut longitudinally and dissected into 1-cm2 pieces. The vessel was placed luminal side down in a petri dish with a coverglass bottom (Mat-Tek) and covered with normal saline. A coverglass and then a brass weight were placed on top of the wetted vessel to flatten it against the bottom of the dish. The sample was immediately placed dorso-ventrally across the microscope stage, and imaged. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with a research protocol (ASP# 0123) approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

2.2. Histological analyses

The aorta with renal arteries was immediately fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin and serial sectioned at thickness of 4 µm through the aorta. The sections were routinely stained with hematoxylin and eosin, Masson tri-chrome, Elastic Van Gieson’s and Movat stains. Histology images were taken by using Leica macro-(M420) and microscopes (DMRXA) with DC500 digital camera.

2.3. Two-photon excitation microscopy

Two-photon images were taken at room temperature with an LSM 510 META microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with a ×10, 0.3-numerical aperture, or, a × 40 1.3-numerical aperture oil-immersion objective (Zeiss). A pulsed Ti:sapphire Laser (Mai-Tai) set at 860 nm was used for excitation, and emission spectra were collected to optimize the separation of collagen and elastin signals, as previously described [16]. LDL was isolated, labeled with Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.), and imaged as previously described [16]. Briefly, collagen second harmonic generation (SHG) was detected at 415–430 nm, elastin fluorescence at 500 to 550 nm, and Alexa Fluor 647 (LDL) at 650–710 nm. Three-dimensional images were collected as a stack of images at 2 µm spacing starting just above the luminal surface. In order to survey the entire porcine renal ostium, arrays of image stacks were collected using the MultiTime Series Macro (Zeiss). The individual z-series were rendered as maximum projection images using Zeiss software and then manually tiled. LDL binding was quantified by measuring the integrated pixel intensity in each section of the z-stack using MetaMorph software.

2.4 Color doppler ultrasound studies

The renal artery and aortorenal bifurcation were exposed by bloodless tissue plane dissection. An incision was made in the left dorsal lateral flank of anesthetized pigs (n=3), allowing direct retroperitoneal access to the aortic entrance to the left renal artery. In this position, the kidney, renal artery, and descending aorta were undisturbed and maintained in their natural positions. Blood velocity profiles were measured at the aortic entrance to the left renal artery of living pigs using a VisualSonics Vevo 2100 Imaging System equipped with a 30 MHz linear transducer, which generated a spectral Doppler frequency of 24 MHz. The probe was placed in contact with the exposed vessels and elicited 80 images per second with a spatial resolution of 50 µm axial and 110 µm lateral in two-dimensional imaging mode. All experiments performed on animals were in accordance with a research protocol (ASP# 0123) approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

3. Results

3.1 Histological analysis of renal ostial structure

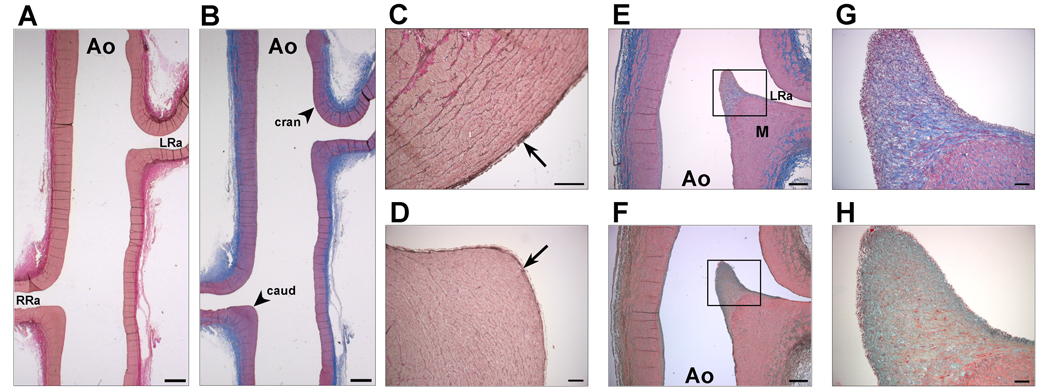

The gross structure of the porcine aorta in the region of the renal arteries was assessed by systematic histological analysis. As shown in Fig. 1, the cranial ostium is similar to the adjacent abdominal aorta with respect to the relative thickness of the intimal layer, inner elastic membrane (IEL), and medial layer. Little, if any, change in wall structure is seen in the transition from aorta to cranial renal ostium to renal artery. The structure of the caudal renal ostium, however, markedly differs from that of the cranial ostium and adjacent abdominal aortic wall. Both the intimal and medial layers of the caudal ostium are thickened, forming an angular, “shelf-like” structure that appears to serve as a flow diverter. Towards the mid-line of the aorta, the caudal renal ostium forms a knife-like structure. In this region, the medial layer of the caudal renal ostium is maximally thickened and is covered by a markedly thickened intimal “cap” that is enriched with both collagen and mucopolysaccharides (shown by Masson’s Trichrome and Movat staining, respectively). Interestingly, the region of maximal enrichment of the intimal cap with mucopolysaccharides is just below the endothelium, whereas the region of maximal enrichment with collagen is in the core region just below the zone of mucopolysaccharide enrichment. In addition, the IEL is thicker in the cranial aspect of the ostium compared to that in the caudal ostium.

Figure 1.

Histological analysis of renal ostial and arterial extracellular matrix. The abdominal aorta (Ao) and the left (LRa) and right (RRa) renal arteries were stained with Elastic Van Gieson’s stain (A, C, D) for elastin (black), Masson’s Trichrome stain (B, E, G) for collagen (blue) and smooth muscle (red), and Movat stain (green) for mucopolysacchride (F, H). Note that the caudal aspect (caud) of both left and right renal ostia (A, B) are thickened, angulated, and appear to be more rigid than the cranial aspect (cran). The inner elastic layer (IEL; arrows) in the cranial (C) aspect of the renal ostium is thicker than in the caudal aspect (D). Near the mid-line of the aorta (E, F), both the intimal (rectangles) and medial (M) layers of the caudal renal ostium are thickened, forming a flow diverter at the entrance to the renal artery. The thickened intimal layer on the caudal side of the renal ostium forms an elongated cap (G,H, rectangles in E, F, respectively). A zone of mucopolysaccharide enrichment (H, green) just below the surface of the caudal ostium surrounds a densely-collagenous core (G, blue) in the intimal “fibrous cap”-like structure. Scale bars: A,B: 1 mm; C,D: 100 µm; E,F: 500 µm; G,H: 10 µm. Representative images from a single animal (n=8).

3.2 Two-photon microscopic analysis of renal ostial extracellular matrix

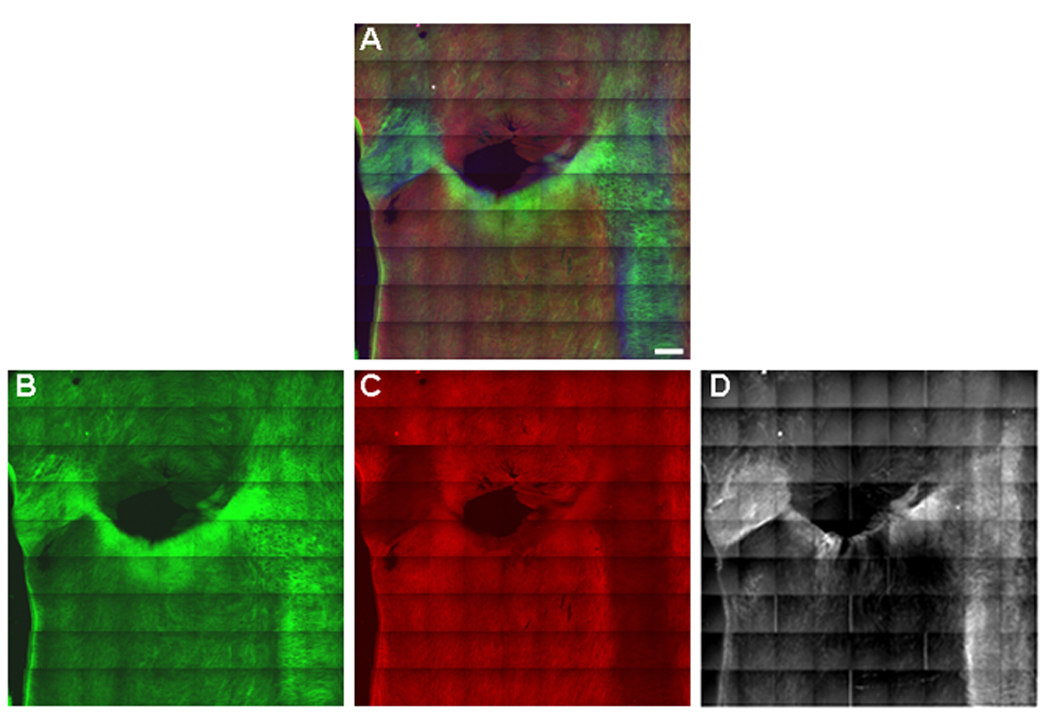

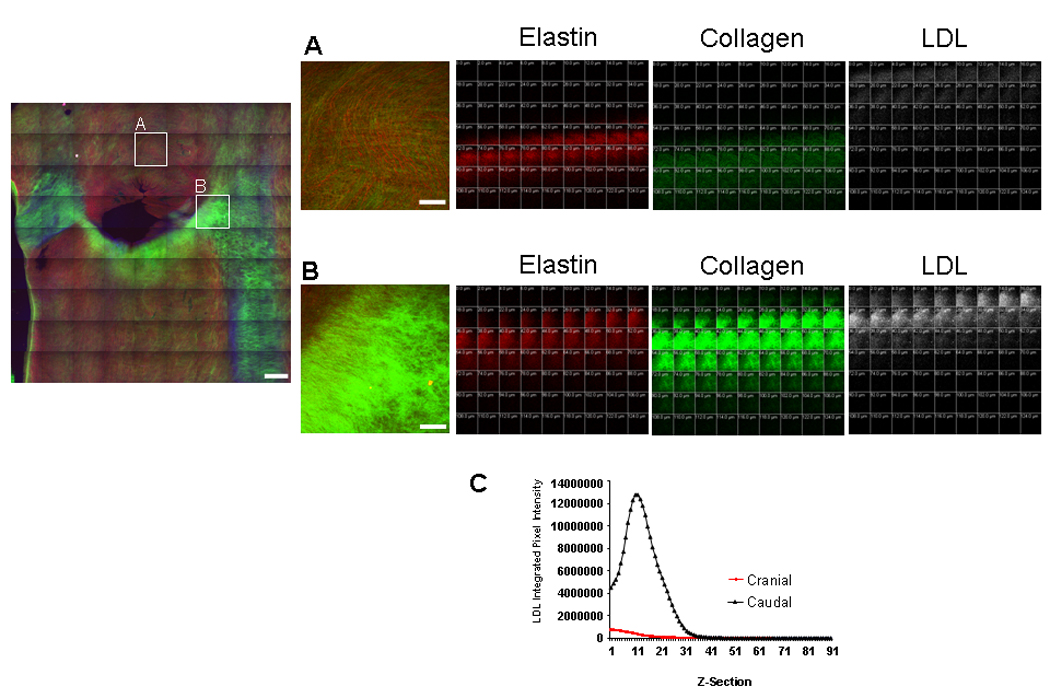

The submicron macromolecular structure of the renal ostium was assessed by two-photon excitation microscopy. Aorta samples were incubated with Alexa Fluor 647-tagged LDL in order to assess the role of macromolecular submicron composition on LDL deposition. A tiled array of z-stacks was imaged using a low magnification objective (×10) to allow sampling of the entire porcine renal ostium with high image resolution. As shown in Fig. 2, the distribution of both collagen and elastin was quite heterogenous along the abdominal aorta. The collagen density in regions of the aorta at a distance from the renal ostium varied from animal to animal. In contrast, the collagen density on the caudal aspect of the renal ostium was markedly increased in every sample examined, as seen in Fig. 2 (and Supplementary Fig. 1). This region of increased collagen density corresponds to the “fibrous cap” structure shown in Fig. 1E,F. There appears to be an inverse relationship between the collagen and elastin content in the abdominal aorta such that densely collagenous regions appear to have lower elastin content whereas collagen–poor regions are elastin-enriched (Fig. 2). Most notably, the elastin content was relatively low in the highly collagenous caudal aspect of the renal ostium, consistent with our histological observations (Fig.1C,D). Fluorescent LDL was observed to bind to the luminal surface of the abdominal aorta in a heterogeneous manner with maximal binding occurring at the collagen-enriched regions, notably the caudal aspect of renal ostium (Fig. 2). LDL bound to the most superficial layers of the aortic surface, starting above the first layer of collagen and then appearing with collagen to a depth of about 40 µm (Fig. 3). Autofluorescence in the arterial wall contributed negligibly to the fluorescent LDL signal (data not shown). LDL binding was increased as much as 25× on the caudal surface relative to the cranial surface (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Distribution of LDL binding at the aortic entrance to the renal artery. Tiled (9×9) two-photon maximum projection of z-series images through 180 µm of the luminal surface of the aortic entrance to the left renal artery. (A) Merged image. Collagen SHG is green, elastin autofluorescence is red, and, Alexa 647-LDL is blue. (B) Collagen. (C) Elastin. (D) LDL. LDL (D) binds eccentrically to the collagen-enriched (B), elastin-poor (C), atherosclerosis-susceptible, caudal side of the renal ostium. Representative images from a single animal (n=6).

Figure 3. LDL binding to the surface of the renal ostium.

(Left) The tiles outlined in the cranial and caudal regions of the renal ostium in Fig. 2 are shown above in (A), and (B), respectively. Scale bar = 1 mm. (Right) Z-series images at 0 – 124 µm from the luminal surface of the aortic wall, for tiles (A), and (B) respectively. Elastin autofluorescence is red, collagen SHG is green, and Alexa 647-LDL fluorescence is white. Collagen is enriched in the caudal compared to the cranial ostium. LDL binding is also greatly enhanced in the caudal compared to the cranial ostium. LDL binding to the surface occurs prior to the appearance of collagen at both the cranial and caudal sites, but overlaps to a considerable extent with collagen in the caudal ostium. Scale bars = 250 µm. (C) LDL integrated pixel intensity was measured for each z-section as described in “Materials and Methods”. LDL binding to the caudal renal ostium (A) was increased 25× compared to the cranial ostium (B). Representative images from a single animal (n=6).

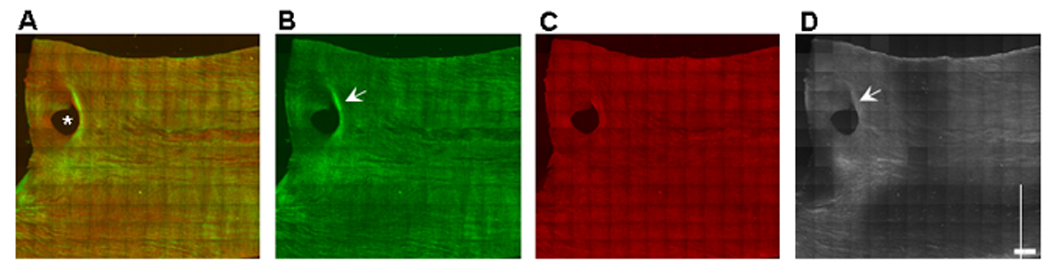

3.3 Two-photon microscopic analysis of renal artery extracellular matrix

As seen in Fig. 4, the distribution of collagen and elastin along the renal artery was heterogeneous. Regions of increased collagen density were observed near the entrance to the aorta. An example of an accessory renal artery, which usually branches off of the right renal artery, can be seen in Fig. 4. Consistent with our observation at the caudal (downstream) side of the aortic entrance to the renal artery, there is increased collagen density and LDL binding on the downstream side of the accessory artery branch point.

Figure 4. Distribution of LDL Binding Along the Renal Artery.

Tiled (13×13) two-photon maximum projection of z-series images through 180 µm of the luminal surface of a portion of the right renal artery. The aortic side of the renal artery is on left. (A) Merged image. Collagen SHG is green, elastin autofluorescence is red. (B) Collagen. (C) Elastin. (D) LDL. The lumen of an accessory renal artery, which emanated from the caudal side of the renal artery, is denoted by the asterisk (*). LDL binding (D) is increased at collagen-enriched (B) regions. The most intense LDL binding is seen near the aortic side of the renal artery (left). A crescent-shaped band of LDL binds to the collagen-enriched (B), elastin-poor (C), zone on the distal (downstream) side (arrows) of the branch point of the accessory renal artery. Scale bar = 1 mm. Representative images from a single animal (n=4).

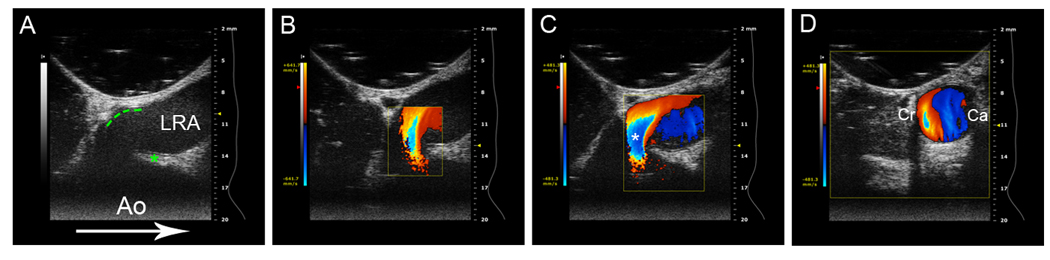

3.3 Color doppler ultrasound studies of blood flow at the entrance to the renal artery

To examine the effects of the renal ostium diverter on blood flow, we conducted high-resolution color Doppler ultrasound studies on the porcine renal artery, in vivo. Previous ultrasound studies of blood flow near the renal ostium have lacked the spatial resolution to identify the flow patterns in this region[17,18] We applied state-of-the-art pulsed Doppler color guided ultrasound technology using a 30-MHz frequency transducer in direct contact with the aortic entrance to the left renal artery in living pigs to obtain high resolution images of blood flow at this site. As shown in Fig. 5A, the caudal aspect of the renal ostium was seen as a projection along the abdominal aorta. Color Doppler ultrasound revealed that the caudal renal ostial projection diverts aortic blood flow into the renal artery, as manifested by the disturbed blood flow at the entrance to the renal artery (Fig. 5B,C) as well as disturbed blood flow downstream in the renal artery near the ostium (Fig. 5C,D). Downstream of the renal artery diverter, blood was observed to flow in opposite directions along the cranial and caudal surfaces of the renal artery. The physiological relevance of the apparent disturbed blood flow at the renal ostium was verified by altering the Doppler velocity. Disturbed blood flow was still observed using higher velocity, eliminating possible aliasing artifacts (data not shown).

Figure 5. Ultrasound imaging of blood flow at the aortic entrance to the left renal artery.

The angle of the ultrasound transducer was progressively rotated to produce longitudinal (A), oblique (B, C) and cross-sectional (D) image planes. (A) Two-dimensional ultrasound image, longitudinal image plane. Aorta (Ao), caudal renal ostial projection denoted by asterisk, cranial renal ostium denoted by green dotted line, left renal artery (LRA). The arrow indicates direction of blood flow in the descending aorta. Note the marked resemblance of the caudal renal ostial projection to the structure seen in Fig 1E. (b) Color image of blood flow at renal ostium, oblique image plane. Variance map on left indicates blood flow velocity. Note disturbed blood flow at the tip of the diverter, indicated by the multivelocity pattern (aliasing). Blue indicates a region of increased blood velocity (flow away from transducer) orange indicates a region of decreased blood velocity (flow towards transducer). (C) A further oblique angle reveals markedly disturbed blood flow at the aortic entrance to the renal artery (denoted by the asterisk), as well as disturbed flow further downstream within the LRA. Note the difference in blood flow velocity impinging on the cranial surface (orange, towards transducer) vs. caudal surface (blue, away from transducer) within the left renal artery. (D) Cross-sectional image plane of the left renal artery just distal to the renal ostium. This image plane corresponds to the region within the LRA in (C). Note the marked difference in blood velocity at the cranial (Cr) vs caudal (Ca) surfaces of the left renal artery is maintained in the cross-section. This image series reveals that the caudal flow diverter disturbs blood flow at both the aortic entrance to the renal artery as well as further downstream within the renal artery.

4. Discussion

We examined the histological structure and macromolecular microstructure of the renal arterial ostium in order to gain insight into the structural determinants of increased atherosclerotic susceptibility at this anatomical site. Surprisingly, we discovered a previously unidentified structure on the caudal aspect of the renal ostium that apparently diverts flow into the renal artery. We characterized the macromolecular structure of this renal diverter as well as the distribution of LDL binding to assess the potential contribution of this structure to the well documented susceptibility of the caudal region of the renal ostium to atherosclerosis.

The renal artery flow diverter is characterized by a specialized intimal thickening in the form of a cap. The subendothelial region of the cap is enriched with mucopolysaccharides and surrounds a dense collagenous core that sits atop a relatively thin inner elastic lamina, which in turn sits above a thickened layer of collagen-enriched medial smooth muscle. Together, the specialized, thickened intimal and medial layers of the caudal ostium form a rigid, knife-like structure that, as confirmed by our color Doppler ultrasound studies, serves to divert blood flow into the renal artery. The diverter projects into the aorta on the order of 1 mm, and is approximately 2.5 mm thick across the opening of the ostium, thereby providing an effective physical device to direct flow into the renal artery. It is tempting to speculate that contraction of the medial smooth muscle in the flow diverter may alter the orientation of the intimal cap, hence the diameter of the renal ostial opening, and consequently, flow into the renal artery. Further studies will be required to confirm this notion. Although not formally described in the literature, the asymmetry in cranial vs caudal ostial geometries can also be seen in published MRIs of human renal arteries [19,20], suggesting that this diverter may not be limited to the porcine renal artery. Stent designs that cover this region might benefit in mimicking the function of this diverter structure.

Examination of the macromolecular microstructure en face of the ostium using novel non-linear optical techniques confirmed the asymmetry seen in the histology studies. These studies also provided more specific information on the macromolecular distribution as well as differences in exposure to the blood on the surfaces around the aortic entrance to the renal ostium. Collagen formed a dense meshwork on the caudal side of the aortic entrance to the renal artery. A most striking finding in these studies was the absence of the elastin surface layer in the renal arterty diverter across the entire caudal region (see Fig. 2&Fig. 4). The stiff structure provided by the collagen-enriched flow diverter (in marked contrast the cranial aspect of the ostium), may reflect the mechanical requirement necessitated by the severe forces applied by the diverter as it redirects aortic flow into the renal artery. Consistent with our observation of increased elasticity on the cranial side of the renal ostium, MRI imaging has revealed that during the breathing cycle, human kidneys and renal arteries move in the cranial direction, altering the renal artery branch angle[19]. Although our color Doppler ultrasound studies demonstrate that the diverter redirects flow into the renal artery generating a highly disturbed flow pattern at the origin of the renal artery, it is still unclear what the quantitative contribution of the diverter is to the net flow into the renal arteries. We would suggest, based on the size of the diverter and the extent to which the velocity gradients are generated, that a significant fraction of the renal artery blood flow may be enhanced by the momentum shift in blood induced by this structure.

LDL binding was assayed using fluorescent Alexa 647-tagged LDL to see if the unique macromolecular structure of the renal ostium could play a role in the increased susceptibility to atherosclerosis in this region. Consistent with our previous observations where LDL was shown to bind in a highly co-operative manner in exposed collagen and proteoglycans in artery branch points[16], LDL was observed to bind to regions in the renal ostium enriched with proteoglycans and collagen that were relatively elastin-poor. LDL binding was enhanced at the crescent-shaped zone of densely-packed collagen on the caudal aspect of the renal ostium comprising the renal artery diverter (Fig. 2). LDL binding at this site is likely underestimated since reaction of Alexa-fluor with lysine residues on apo B-100 may reduce the positive charge of its proteoglycan binding groups.

Lipid deposition occurs at this very site in human renal ostia prior to the formation of atherosclerotic lesions [10]. Moreover, the caudal aspect of the renal ostium is the initiation site of atherosclerotic lesions in humans [4,5] and in the diet-induced rabbit model [6,7]. The observed enhancement in LDL binding to the collagen and proteoglycan enriched caudal ostium provides a mechanistic link between these two previous observations. The enhanced susceptibility of the caudal aspect of the renal artery ostia to atherosclerosis is likely a direct result of the renal artery flow diverter structure exposing collagen and proteoglycans to the vascular compartment and circulating LDL. Further studies are needed to determine whether age- or disease-induced changes in the structure of the renal ostial diverter alters blood flow dynamics thereby providing an additional mechanism for atherosclerotic lesion progression.

In summary, this study characterized the gross and fine structure of the porcine renal artery ostium. A novel renal artery diverter was described which redirects aortic flow into the renal artery, as observed using high-resolution ultrasound. The mechanical requirement for aortic flow diversion is likely to be responsible for the dense collagen/proteoglycan content in the diverter which, in turn, is responsible for excessive retention of LDL at this site. Thus, the macromolecular composition of the renal ostium may contribute to the caudal susceptibility to atherosclerosis observed in both animals and humans.

Supplementary Material

Gallery of renal ostia. Tiled two-photon maximum projection of z-series, merged images of the aortic entrance to the renal artery. Collagen SHG is green, elastin autofluorescence is red, and, Alexa 647-LDL is blue. Note the crescent-shaped band of collagen-enriched matrix that forms the caudal aspect of the renal ostium.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank John Stonik for his help in the preparation of fluorescent LDL used in these studies, and the members of the Laboratory of Cardiac Energetics, notably, Jamie Schroeder, Darci Phillips and David Chess, for their useful comments and suggestions during the course of this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Safian RD, Textor SC. Renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:431–442. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cicuto KP, McLean GK, Oleaga JA, Freiman DB, Grossman RA, Ring EJ. Renal artery stenosis: anatomic classification for percutaneous transluminal angioplasty. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1981;137:599–601. doi: 10.2214/ajr.137.3.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaatee R, Beek FJ, Verschuyl EJ, vd Ven PJ, Beutler JJ, van Schaik JP, et al. Atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: ostial or truncal? Radiology. 1996;199:637–640. doi: 10.1148/radiology.199.3.8637979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen ND, Haque AK. Effect of hemodynamic factors on atherosclerosis in the abdominal aorta. Atherosclerosis. 1990;84:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(90)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanganelli P, Bianciardi G, Simoes C, Attino V, Tarabochia B, Weber G. Distribution of lipid and raised lesions in aortas of young people of different geographic origins (WHO-ISFC PBDAY Study). World Health Organization-International Society and Federation of Cardiology. Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth. Arterioscler Thromb. 1993;13:1700–1710. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.13.11.1700. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Ivey J, Roach MR, Kratky RG. A new probability mapping method to describe the development of atherosclerotic lesions in cholesterol-fed rabbits. Atherosclerosis. 1995;115:73–84. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(94)05501-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kratky RG, Ivey J, Roach MR. Local changes in collagen content in rabbit aortic atherosclerotic lesions with time. Atherosclerosis. 1999;143:7–14. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(98)00250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakashima Y, Fujii H, Sumiyoshi S, Wight TN, Sueishi K. Early human atherosclerosis: accumulation of lipid and proteoglycans in intimal thickenings followed by macrophage infiltration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1159–1165. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.106.134080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stary HC, Chandler AB, Glagov S, Guyton JR, Insull W, Jr, Rosenfeld ME, et al. A definition of initial, fatty streak, and intermediate lesions of atherosclerosis. A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1994;89:2462–2478. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.5.2462. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Sinzinger H, Silberbauer K, Auerswald W. Quantitative investigation of sudanophilic lesions around the aortic ostia of human fetuses, newborn and children. Blood Vessels. 1980;17:44–52. doi: 10.1159/000158233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stary HC. Macrophages, macrophage foam cells, and eccentric intimal thickening in the coronary arteries of young children. Atherosclerosis. 1987;64:91–108. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(87)90234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stary HC. Lipid and macrophage accumulations in arteries of children and the development of atherosclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:1297S–1306S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.5.1297s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boren J, Olin K, Lee I, Chait A, Wight TN, Innerarity TL. Identification of the principal proteoglycan-binding site in LDL. A single-point mutation in apo-B100 severely affects proteoglycan interaction without affecting LDL receptor binding. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2658–2664. doi: 10.1172/JCI2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camejo G, Olofsson SO, Lopez F, Carlsson P, Bondjers G. Identification of Apo B-100 segments mediating the interaction of low density lipoproteins with arterial proteoglycans. Arteriosclerosis. 1988;8:368–377. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.8.4.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiklund O, Camejo G, Mattsson L, Lopez F, Bondjers G. Cationic polypeptides modulate in vitro association of low density lipoprotein with arterial proteoglycans, fibroblasts, and arterial tissue. Arteriosclerosis. 1990;10:695–702. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.10.5.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon GP, Schroeder JL, Amar MJ, Remaley AT, Balaban RS. Contribution of macromolecular structure to the retention of low-density lipoprotein at arterial branch points. Circulation. 2008;117:2919–2927. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.754614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto T, Tanaka H, Jones CJH, Lever MJ, Parker KH, Kimura A, et al. Blood Velocity Profiles in the Origin of the Canine Renal-Artery and Their Relevance in the Localization and Development of Atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis and Thrombosis. 1992;12:626–632. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.5.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamamoto T, Ogasawara Y, Kimura A, Tanaka H, Hiramatsu O, Tsujioka K, et al. Blood velocity profiles in the human renal artery by Doppler ultrasound and their relationship to atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. 1996;16:172–177. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.1.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Draney MT, Zarins CK, Taylor CA. Three-dimensional analysis of renal artery bending motion during respiration. J Endovasc Ther. 2005;12:380–386. doi: 10.1583/05-1530.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leiner T, Michaely H. Advances in contrast-enhanced MR angiography of the renal arteries. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2008;16:561–72. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Gallery of renal ostia. Tiled two-photon maximum projection of z-series, merged images of the aortic entrance to the renal artery. Collagen SHG is green, elastin autofluorescence is red, and, Alexa 647-LDL is blue. Note the crescent-shaped band of collagen-enriched matrix that forms the caudal aspect of the renal ostium.