Abstract

Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) is a bullet-shaped rhabdovirus and a model system of negative-strand RNA viruses. Based on direct visualization by cryo-electron microscopy, we show that each virion contains two nested, left-handed helices, an outer helix of matrix protein M and an inner helix of nucleoprotein N and RNA. M has a hub domain with four contact sites that link to neighboring M and N subunits, providing rigidity by clamping adjacent turns of the nucleocapsid. Side-by-side interactions between neighboring N subunits are critical for the nucleocapsid to form a bullet shape, and structure-based mutagenesis results support this description. Together, our data suggest a mechanism of VSV assembly in which the nucleocapsid spirals from the tip to become the helical trunk, both subsequently framed and rigidified by the M layer.

VSV is an enveloped, bullet-shaped, non-segmented, negative strand RNA virus (NSRV) belonging to the rhabdovirus family, which includes rabies virus. As some attenuated VSV strains are non-toxic to normal tissue, VSV has therapeutic potential as an anti-cancer agent and vaccine vector (1, 2). Furthermore, pseudo-types of VSV carrying receptors for HIV proteins can selectively target and kill HIV-1 infected cells and control HIV-1 infection (3, 4).

Whereas many other NSRVs are pleomorphic, VSV has its unique rigid bullet shape. Attempts to visualize its organization by negatively stained electron microscopy have resulted in limited 2D pictures: the virion has a lipid envelope (decorated with G spikes) that encloses a nucleocapsid composed of RNA plus nucleoprotein N and an associated matrix formed by M proteins. In recent years, crystal structures of components of VSV have been determined: the C-terminal core domain MCTD of the matrix protein (M) (5, 6), the nucleoprotein (N) (7), the partial structure of phosphoprotein (P) (8), the N/P(C-terminal Domain) complex (9) and the two forms of the ectodomain of the glycoprotein (G) (10, 11). The large polymerase (L) still awaits structure determination. However, how these proteins assemble into the characteristic rigid “bullet”-shaped virion has not been clear. Here, we report the 3D structure of the helical portion (the “trunk”) of the VSV virion determined by cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM) as well as a study of the bullet-shaped tip from an integrated image processing approach. This analysis leads us to propose a model for assembly of the virus with its origin at the bullet tip.

CryoEM images of purified VSV virions show intact bullet-shaped particles almost devoid of truncated or defective interference particles (Fig. 1A). The reconstructed map of the virion trunk (Fig. 1B, online movies S1, S2) has an effective resolution of 10.6Å based on the 0.5 Fourier shell correlation coefficient criterion (fig. S2). We were able to dock crystal structures of the C-terminal domain of M (PDB:1LG7 or 2W2R) (5, 6) and all of N (PDB:2GIC) (7) into our cryoEM density map. The matching of several high-density regions in the cryoEM map with α helices in the docked atomic models (M in Fig. 2A; N in Fig. 3A) supports the validity of the cryoEM map. These dockings also establish the chirality of the structure.

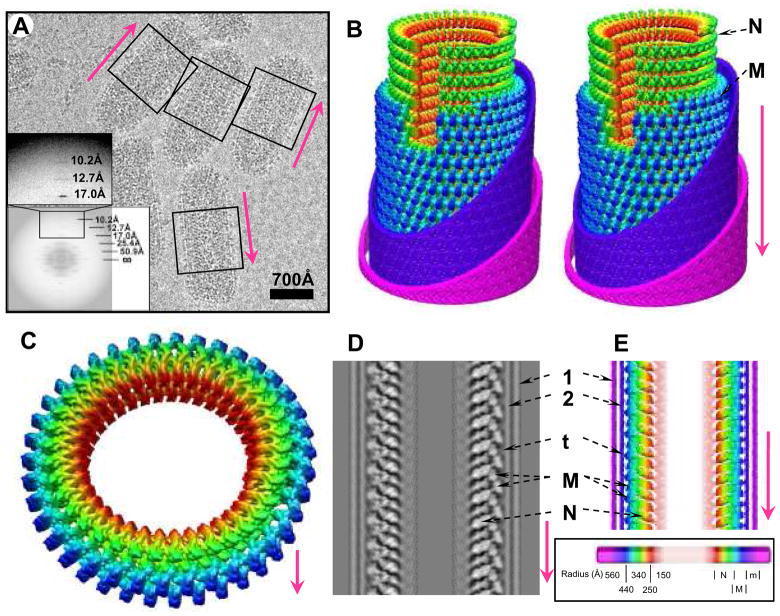

Figure 1. CryoEM of VSV virion and 3D reconstruction of its helical trunk.

(A) A typical cryoEM micrograph of VSV virions at 98,000x magnification. The trunk portion is marked by the boxes; inset, incoherent average of Fourier transforms of all raw images showing the layer lines. (B) Density map of the virion trunk. To enhance visual clarity and to show the interior, we computationally removed four turns of M, part of the membrane bilayer, incomplete subunits, and a 30° wedge. Nucleocapsid N and matrix M layers were displayed at a threshold of 1.15σ above the mean; envelope densities were displayed at a threshold of 0.1σ above the mean. (C) A complete repeat of the N and M helices, featuring 75 helical asymmetric units in two turns. (D) The central, vertical slice (17.3Å thick) in the density map and (E) a radially color-coded surface representation of a central slab (23Å thick). 1 and 2: outer and inner leaflets of the phospholipid bilayer envelope; t: putative cytoplasmic tail of G; M: matrix protein; N: nucleoprotein. Inset: Coloring scheme -- maps in all panels are colored according to radial distance as depicted in the scale bar. N: Nucleoprotein (red to green); M: Matrix protein (cyan to blue); e: envelope membrane (violet to pink). In this and the following figures, the arrow in every panel denotes the directionality (tip to trunk) of virions along the axis of the helix or of parts as they would be in the virion.

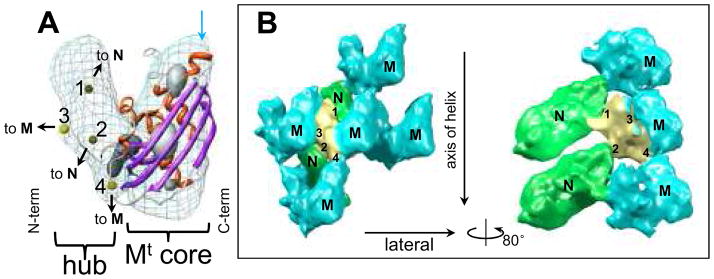

Figure 2. In situ structure of the full length M matrix protein.

(A) Fit of the crystal structure (ribbon) of the C-terminal core domain MCTD (right part) of M into the corresponding density map (mesh, contoured at 1.15σ above the mean), taken from the cryoEM map. The α helices are shown in red and β sheets in purple. The numbered yellow spheres in the left part of the density map mark the positions of the four contact points on the “M-hub” domain. The highest density regions of the cryoEM density are shown as gray shaded surface by contouring at 3.0σ above the mean. (B) Left: four adjacent M (cyan) with two N (green) subunits in the neighborhood of one M with its M-hub in yellow. The contact points on the M-hub that mediate interactions with M and N are labeled 1–4. The volume is contoured at 1.0σ. Right: by turning the left panel 80° around the vertical axis and removing the frontal M subunit, the interaction between N and M is illustrated.

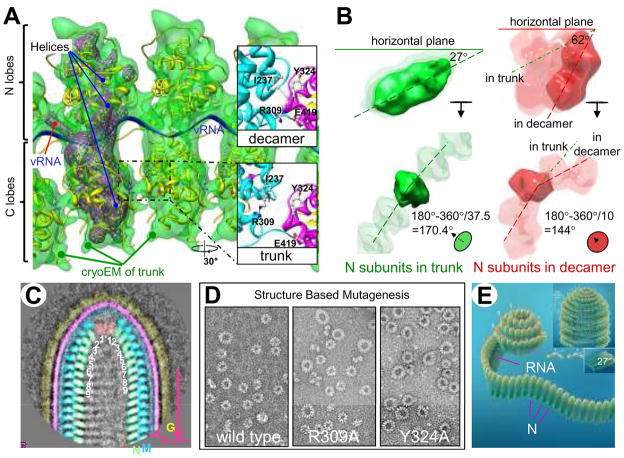

Figure 3. Formation of the “bullet” tip of VSV virion by the nucleocapsid (N) ribbon.

(A) Fitting of the crystal structure (7) of nucleoprotein (N) (yellow ribbon) and RNA (blue ribbon) into the cryoEM density map (semi-transparent green, displayed at a threshold of 1.5σ above the mean) from the VSV virion trunk. The helical axis in this panel points toward the reader. The purple wire frames represents the highest density regions of the cryoEM structure (threshold of 3.5σ above the mean), which co-localize with α helices and the vRNA of the crystal structure. Insets: Along the upper part of the interface between adjacent C lobes in the decamer, there are six hydrogen bonds (including R309 to E419) and one (I237:Y324) hydrophobic interaction (top right inset). Following flexible docking of the atomic structure from the decamer into the cryoEM density map of the trunk, distances between amino acid partners in these seven sites increase by ~9Å, disrupting these interactions. (B) Comparison of the inclination of N subunits (green) in our cryoEM structure from the trunk of the virion (37.5 subunits/turn) with the inclination of the N subunits (red) in the crystal structure from the decamer ring (10 subunits/turn) (7). Top panels: Dashed lines through a side view of an N subunit from the trunk (left) and with an N subunit from the decamer (right) show the difference in tilt, the angle up from the horizontal plane. Bottom panels: Dashed lines through end-on views of N subunits show the difference in dihedral angle between adjacent N subunits in the trunk (green) and in the decamer ring (red). (C) A representative class-average of the virion tip from 75 individual images. Numbers inside the nucleocapsid designate the order of N subunits in the nucleocapsid ribbon, which may be traced by following the path 1 > 1′ > 2 > 2′, etc. (D) Negative stain electron microscopy images of the wild type decamer and two mutant rings confirm the importance of two of the interactions specified above. Both mutants produce rings larger than a decamer. (E) A cartoon illustration of a plausible process by which the nucleocapsid ribbon generates the virion head, starting with its bullet tip. The curling of the nucleocapsid ribbon generates a decamer-like turn at the beginning, similar to the crystal structure. When assembly nearly completes this turn, continuation of vRNA requires that the ribbon form a larger turn below it, similar to that in the mutants in (D). As the spiral enlarges and progresses to the helical trunk, the tilt of individual N subunits decreases. When it reaches the 7th turn, the nucleocapsid ribbon becomes helical (insets), where each new turn of the nucleocapsid fits naturally under the preceding turn (insets).

When reconstructed with helical symmetry imposed (see Methods), the 3D map includes an outermost lipid bilayer, a middle layer composed of a helix-based mesh of M, and an innermost condensed nucleocapsid composed of a helically organized string of N subunits and RNA (Fig. 1B–C, fig. S3). [The M (Fig. 2A) and N (Fig. 3A) layers were identified on the basis of their close match with their crystal structures of M (5, 6) and N (7).] Each of the N and M layers is comprised of a single helix (1-start helix). Although the interior of the nucleocapsid contains a denser region than background, no density was found reasonably attributable to individual P or L subunits, suggesting that those are organized in a lower-symmetric or asymmetric fashion (see Discussion in Supporting Online Material.). A layer of density outside the membrane may be identified as G protein (fig. S1), since the G protein is the only envelope protein in VSV. However, individual G spikes cannot be resolved in this layer, possibly due to flexibly attached ectodomains or inconsistent symmetry, and this layer of density was subsequently removed from the 3D reconstructions (see SOM).

The outer diameter of the outer leaflet of the lipid bilayer measures 700Å. The exact length of the virion varies, 1960±80Å. The conical end comprises ~25%, the cylindrical (helical) trunk ~75%. The conical end contains ~7 turns of a spiral before reaching a cylindrical (helical) trunk. The trunk of a typical virion contains ~29 turns. Each turn contains exactly 37.5 asymmetric units and rises 50.8Å along the helical axis; two turns form a helical repeat (Fig. 1C). This value, 37.5, is very close to that estimated previously from scanning transmission electron microscopy [38 subunits/turn (12)] and from the N crystal structure [38.5 subunits/turn (7)]. Below, we also suggest that this value is consistent with geometric constraints on placement of G-trimers.

Docking of the crystal structure of N and RNA into the cryoEM structure of the nucleocapsid also allows us to establish the directionality of vRNA in the virion. The docked crystal structure shows that the 5′ end is at the conical tip of the “bullet”, the 3′ end at the base of the trunk. We therefore follow this convention: the bullet tip defines the origin, and the helical trunk is “downward” from the origin. Arrows in figures follow this convention.

The full-length M protein in the cryoEM structure of the virion trunk has two domains. The C-terminal domain (MCTD) was solved by X-ray crystallography (6), and we show the crystal structure fitted as ribbons in Figure 2A. (The cross-correlation coefficient between the cryoEM map and the fitted MCTD structure blurred to 11Å is 0.63.) The α helices of the MCTD crystal structure co-localize with the highest density regions in the cryoEM map. The N-terminal domain (the “M-hub”), which was not resolved in the crystal structures (5, 6), points toward the N layer (see SOM and fig. S5). The volume of the M-hub is consistent with its amino acid sequence length of 57 residues.

The M-hub contains four contact sites (labeled 1–4 in Fig. 2A,B and also colored yellow in Fig. 2B). M-hub contact-point 1 connects the M-hub to an N subunit from the upper helical turn, while M-hub contact-point 2 connects the M-hub to an N subunit from the lower helical turn. (By our convention, “upper” and “lower” are toward and away from the conical tip.) These dual vertical interactions set the M helix in an interleaved position between N helix turns and should provide stability and rigidity for the nucleocapsid as well as the M helix in the virion. These observations are consistent with results from mutagenesis, which show that amino acids 4–21 (in the M-hub) are important for nucleocapsid binding and viral assembly (13).

M-hub contact-point 3 binds laterally to MCTD of the trailing M subunit from the same helical turn while contact-point 4 binds to the tip of the MCTD domain of the M subunit from an upper helical turn. The binding of M-hub contact-point 4 sets the vertical spacing of adjacent turns of the M helix and by extension that of the N helix. It can be regarded as a “frame” that holds the N helix. It also leads to the formation of the 2D triangularly packed array (or “mesh”) within the outer (M) helix.

The protein-protein interactions revealed in our structure agree well with previous studies. For example, the surface of MCTD complementary to contact-point 4 includes amino acids 120–128 (cyan arrow at the upper right of Fig. 2A). Proteolytically opening this segment disrupts interactions between Mth and full length M and thus disrupts virion assembly (5, 14, 15). Also, in a recent structural study of full-length M, most of the M-hub is disordered and therefore poorly resolved, but M-hub contact-point 4 (amino acids 41 to 52) along with its binding partner (MCTD residues 120–128) are well resolved (6), consistent with our finding that M-hub contact-point 4 and the loop participate in binding. In addition, the self-association of M appears to follow nucleated polymerization, the “nucleus” consisting of three to four M subunits (16). Here, we suggest that these subunits join with each other at contact-sites “3”.

N subunits encapsidate and sequester the genomic viral RNA (vRNA) and form a higher order linear structure in the shape of a ribbon through intermolecular interactions (fig. S3) (17). In our cryoEM structure, the nucleocapsid is present as a helical tube with an inner radius of 154Å and an outer radius of 225Å (fig. S3). Individual N proteins within the helically coiled ribbon (green subunits in Fig. 3B) tilt upward by 27° from the horizontal plane (the plane perpendicular to the helical axis). Constrained by the 752 screw axis, one N subunit sits below and exactly in the gap between two other subunits from the turn above it (Fig. 1B, fig. S3). As seen from the volume representation (fig. S3), the turns of N are not densely packed against one another in the vertical direction. Thus, in the absence of the overlying M helix, the formation of a rigid nucleocapsid core would be impossible.

The crystal structure of an individual N subunit and its associated RNA has been solved for a ring of ten N subunits, a “decamer ring” (7). This crystal structure can be unambiguously fitted into our cryoEM density map. (The cross-correlation coefficient between the cryoEM map and the final fitted N structure blurred to 11Å is 0.70.) Each N subunit can be divided into an N-terminal lobe (N lobe, top of Fig. 3A) and a C-terminal lobe (C lobe, bottom of Fig. 3A) (Online Movie S3). The N lobe points radially away from the helix axis and interacts with M proteins at its outer surface (top of Fig. 3A). As revealed in the crystal structure of the N decamer ring, RNA threads in a groove between the N lobe and the C lobe (Fig. 3A, Online Movie S3). The density that connects adjacent N lobes is their bound viral RNA. The cryoEM structure of the C lobe in the trunk also agrees well with its crystal structure in the decamer. It has a more globular shape than the N lobe and faces the inner cavity (downward in Fig. 3A). In contrast to N lobes, C lobes bind to one another and therefore establish the lateral interactions in the inner (N) helix.

All rhabdoviruses have a bullet-shaped architecture. The 2D classification of cryoEM images of bullet tips shows that these conical parts are identical among images (Fig. 3C and fig. S1). In all class-averages, the nucleocapsid begins with fewer subunits per turn at the tip, progressing downward to the helical form in ~7 turns. How does the nucleocapsid complete this structural arrangement? When the N crystal structure of the decamer ring is fitted into the trunk portion of a virion with 37.5 subunits/turn, the interface between the C lobes of adjacent N subunits must open significantly because of the larger dihedral angle between adjacent N subunits (Fig. 3B, lower panel, left vs. right). As a result, the six hydrogen bonds (including Glu419/Arg309) and the one hydrophobic interaction (Tyr324 to a pocket composed of Ile237 and part of Arg309) observed in the decamer are pulled apart by ~9Å in the trunk portion of the virion (Fig. 3A, cf. insets). These seven interactions might be used to achieve different energy modes for the formation of N rings of different sizes. Our mutagenesis studies support this hypothesis: Mutating either Arg309 or Tyr 324 to Ala results in a preference for rings larger than the decamer observed in the wild type (Fig. 3D, table S1, see detailed discussion in the SOM).

We propose that assembly starts at the apex of the virion tip, consistent with earlier suggestions (18). The nucleocapsid forms the sharp tip by using the first mode, as found in the decamer ring. Indeed, as shown in the 2D class averages, the first turn of the nucleocapsid matches the shape and size of projection images of the decamer ring (Fig. 3C and fig. S1). As it finishes one turn, the continuation of the viral RNA strand forces the nucleocapsid from the first mode to one with a larger diameter, fewer interactions and higher free energy. Indeed, mutating R309 or Y324 to alanine (i.e., artificially breaking one of the above seven interactions) appears to reduce the probability of the smallest ring size and promote formation of larger rings (Fig. 3D). At the same time, stacking the second turn of the nucleocapsid onto the preceding turn permits binding of M. (Our 2D class averages of the base region of the virion show that the lowest turn of M lies between the lowest two turns of N (Fig. 4A, inset), suggesting that each M subunit must bind simultaneously to two N subunits.) A similar scenario continues until the nucleocapsid reaches its last mode, the mode that can repeat helically and contains a constant number of 37.5 subunits per turn in the trunk. This mode in turn might be stabilized by new interactions.

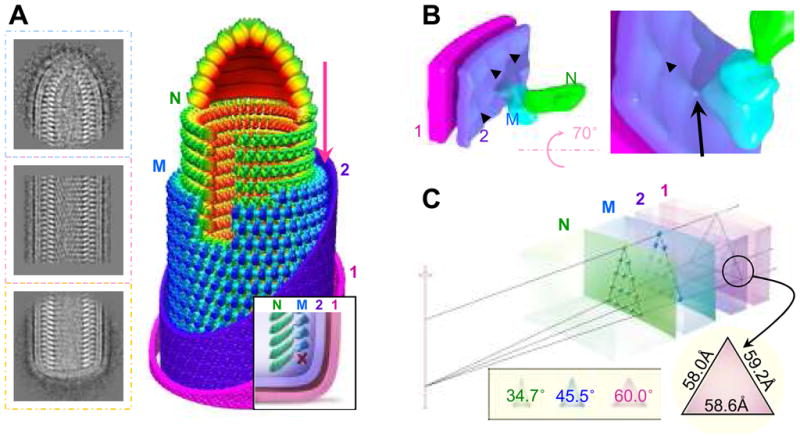

Figure 4. Architecture of the VSV virion and implication for pseudotyping.

(A) Representative 2D averages of conical tip, trunk and base of VSV and a montage model of the tip and the cryoEM map of the trunk. N is green, M is blue, and the inner (“2”) and outer (“1”) leaflets of the membrane are violet and pink. Inset: illustration of the base region of the VSV virion. The “X” marks the absence of a turn of M helix below the lowest turn of the N helix. (B) CryoEM structure showing the putative cytoplasmic tail of G protein binding to an M subunit through a thin linker. The inner leaflet (“2”) of the membrane has unusual bumps (arrowhead) that meet M at the site of a thin linker density (arrow). (C) A wedge of the virion trunk, illustrating its geometric arrangement across the three layers. The N layer, the M layer, and the two membrane leaflets (“1” and “2”) are arranged in coaxial cylinders with their radii determined from our cryoEM structure. Due to the difference in radii, the helical lattice points on the three layers form different triangles. The smaller the radius, the narrower the apex angle (inset). At the outer surface of the membrane, the lattice points form an equilateral triangle.

The M helix forms a triangularly packed lattice of M subunits (Figs. 1B, 4A). Next to the outer surface of the M helix, envelope membrane density intrudes inward at sites centered on each M subunit. There, a thin linker density runs from the membrane to contact an M subunit (Fig. 4B). This density is likely to be the cytoplasmic tail of a G protein, which is known to interact with M and is critical for budding(19, 20). Presumably, the G protein trimer binds three underlying M simultaneously (see Discussion in SOM). If the trimer has 3-fold symmetry, the binding slots for G on the outside of the envelope membrane need to be an equilateral triangle. Indeed, we find that these sides are 58.6Å, 59.2Å and 58.0Å at the outer surface of the membrane. This geometric arrangement requires that the lateral spacing of M and N subunits within the M and N helices, each with progressively smaller diameters from G to M to N layers, be smaller and smaller. Our measurement of apex angles confirms that requirement (Fig. 4C). Given the base and height dimensions of N and M proteins and the 27° tilt from the horizontal plane, these triangular relationships are satisfied only with 37.5 subunits per turn.

Assembly of a virus particle is generally presumed to be a stochastic process. However, assembly of VSV appears to follow a well orchestrated program. It begins with RNA and N as a nucleocapsid ribbon (Fig. 3E). The ribbon curls into a tight ring and then is physically forced to curl into larger rings that eventually tile the helical trunk (Fig. 3E). M subunits bind on the outside of the nucleocapsid, rigidify the bullet tip and then the trunk, and create a triangularly packed platform for binding G trimers and envelope membrane, all in a coherent operation during budding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Shihong Qiu and Xin Zhang for their technical assistance, Xiaorui Zhang for assistance in graphics, and Mary Yang for proof-reading the manuscript. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants AI050066 (ML) and GM071940 (ZHZ) and AI069015 (ZHZ). PG was supported in part by a training fellowship from the W.M. Keck Foundation to the Gulf Coast Consortia through the Keck Center for Virus Imaging. The first octant of the helical reconstruction map of the virion trunk and its key segmentations have been deposited with the EMDB (accession code: EMD-1663). Flexibly fitted coordinates of N into our cryoEM density have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank (accession code: 2WYY).

References and Notes

- 1.Lichty BD, Power AT, Stojdl DF, Bell JC. Trends Mol Med. 2004 May;10:210. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stojdl DF, et al. Cancer Cell. 2003 Oct;4:263. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00241-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnell MJ, Johnson JE, Buonocore L, Rose JK. Cell. 1997 Sep 5;90:849. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80350-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mebatsion T, Finke S, Weiland F, Conzelmann KK. Cell. 1997 Sep 5;90:841. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaudier M, Gaudin Y, Knossow M. EMBO J. 2002 Jun 17;21:2886. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham SC, et al. PLoS Pathog. 2008 Dec;4:e1000251. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green TJ, Zhang X, Wertz GW, Luo M. Science. 2006 Jul 21;313:357. doi: 10.1126/science.1126953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding H, Green TJ, Lu S, Luo M. J Virol. 2006 Mar;80:2808. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2808-2814.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green TJ, Luo M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Jul 14;106:11713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903228106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roche S, Bressanelli S, Rey FA, Gaudin Y. Science. 2006 Jul 14;313:187. doi: 10.1126/science.1127683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roche S, Rey FA, Gaudin Y, Bressanelli S. Science. 2007 Feb 9;315:843. doi: 10.1126/science.1135710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas D, et al. J Virol. 1985 May;54:598. doi: 10.1128/jvi.54.2.598-607.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Black BL, Rhodes RB, McKenzie M, Lyles DS. J Virol. 1993 Aug;67:4814. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4814-4821.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connor JH, McKenzie MO, Lyles DS. J Virol. 2006 Apr;80:3701. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.8.3701-3711.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaudin Y, Barge A, Ebel C, Ruigrok RW. Virology. 1995 Jan 10;206:28. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(95)80016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaudin Y, et al. J Mol Biol. 1997 Dec 19;274:816. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X, Green TJ, Tsao J, Qiu S, Luo M. J Virol. 2008 Jan;82:674. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00935-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Odenwald WF, Arnheiter H, Dubois-Dalcq M, Lazzarini RA. J Virol. 1986 Mar;57:922. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.3.922-932.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitt MA, Chong L, Rose JK. J Virol. 1989 Sep;63:3569. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.3569-3578.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou Y, Konig M, Hobom G, Neumeier E. Virology. 1998 Jun 20;246:83. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.