Abstract

Chronic pain and obesity, and their associated impairments, are major health concerns. We estimated the association of overweight and obesity with five distinct pain conditions and three pain symptoms, and examined whether familial influences explained these relationships. We used data collected from 3,471 twins in the community-based University of Washington Twin Registry. Twins reported sociodemographic data, current height and weight, chronic pain diagnoses and symptoms, and lifetime depression. Overweight and obese were defined as body mass index of 25.0 – 29.9 kg/m2 and ≥ 30.0 kg/m2, respectively. Generalized estimating equation regression models, adjusted for age, gender, depression, and familial/genetic factors were used to examine the relationship between chronic pain, and overweight and obesity. Overall, overweight and obese twins were more likely to report low back pain, tension-type or migraine headache, fibromyalgia, abdominal pain, and chronic widespread pain than normal weight twins after adjustment for age, gender, and depression. After further adjusting for familial influences, these associations were diminished. The mechanisms underlying these relationships are likely diverse and multifactorial, yet this study demonstrates that the associations can be partially explained by familial and sociodemographic factors, and depression. Future longitudinal research can help to determine causality and underlying mechanisms.

Keywords: Chronic Pain, Genetics, Heritability, Obesity, Twins

INTRODUCTION

Chronic pain and obesity are highly prevalent conditions associated with substantial impairments, and responsible for a large portion of physician visits and healthcare costs 26, 29, 49. Based on recent estimates, 65% of all adults were either overweight or obese, and these rates have dramatically increased in recent years 46, 49. The annual cost of obesity was estimated to be $118 billion. Likewise, chronic pain is one of the most prevalent complaints in primary care affecting over 50 million people, resulting annually in an estimated $70 billion in direct healthcare expenditures and lost productivity 2, 27, 30, 49.

Several studies have examined the co-occurrence of chronic pain conditions and obesity. Osteoarthritis and back pain, two of the most common chronic pain conditions, commonly co-exist with obesity 35, 37. Other cross sectional studies have found associations between obesity and fibromyalgia 45, 67, 69, chronic headaches 8, 52, abdominal pain 16, 56, and arthritis 14. Prospective studies indicate that overweight and obese individuals are at greater risk for chronic pain because the additional weight increases pressure on the joints creating structural changes in the body that cause pain 7, 33, 35, 61. Alternately, chronic pain may result in weight gain and obesity by reducing physical activity 32, 62. Genetic, psychological, or metabolic processes, may also contribute to developing both conditions 13, 62. For example, depression has been associated with both chronic pain, and overweight and obesity 4, 42 and studies in monozygotic twins suggest genetic factors may explain the link between chronic low back pain and obesity 36.

Although chronic pain conditions are likely multifactorial and co-occur with overweight or obesity, few studies have examined familial and genetic contributions to, or the role of, psychological factors in the relationship between these conditions. In this study, we used data from a large community-based sample of twins to examine the relationship of five distinct pain diagnoses and three pain symptoms with overweight and obesity. We sought answers to these questions: 1) Are diverse chronic pain diagnoses and symptoms associated with being overweight or obese? 2) Does depression contribute to the associations between chronic pain, and overweight and obesity? and 3) Do familial factors including shared genetic and common environmental factors contribute to these associations?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

All twins were participants in the University of Washington Twin Registry, a community-based sample of twins derived from the drivers' license applications of the Washington State Department of Licensing 1. In Washington State drivers' license numbers are derived from a person's name and date of birth, thus, the Department of Licensing asks every new applicant if s/he is a twin to avoid issuing duplicate license and identification numbers to twins. The University of Washington Twin Registry receives lists of applicants who are twins, and each member of the pair is invited to join the Registry and complete a health survey. The brief survey contains items on demographics, habits, physician-diagnosed health conditions, symptoms, healthcare use, and various abridged, standardized measures of physical and mental health. Full details of the construction and characteristics of the University of Washington Twin Registry, including response rates, are described elsewhere 1. All Registry and data collection procedures involved in this study were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board and the State of Washington Attorney General. Informed consent was obtained from all twins.

Measures

Zygosity assignment

As part of the mailed questionnaire, all twins were asked questions about childhood similarity to assess zygosity. Studies in both U.S. and Scandinavian twin registries have shown that questions about childhood similarity in twin pairs can be used to correctly classify zygosity with an accuracy of 95% to 98% compared with zygosity determined by biological indicators 50, 60. Responses to these similarity questions were used in a multi-step process to assign zygosity. Opposite-sex twin pairs were excluded from the study because sex differences in height and weight would not allow us to capitalize on the matched nature of the twin sample.

Sociodemographic factors

Sociodemographic factors collected in the survey included age, sex, race and ethnicity, education, and marital status.

Depression

Lifetime depression was assessed by endorsement of a single item on depression. Twins were given a list of conditions including depression and asked: “Has your doctor ever told you that you have any of the following conditions?”

Chronic pain diagnoses

A lifetime history of low back pain, tension-type or migraine headache, irritable bowel syndrome, temporomandibular joint or muscle disorder, and fibromyalgia were also assessed by self-report of a diagnosis by a physician.

Chronic pain symptoms

Several other questions asked about pain-related symptoms during the previous three months. One asked about abdominal pain that is relieved with bowel movements or associated with loose stools or constipation 58, 59. Another question asked about persistent or recurrent pain in the face, jaw, temple, in front of the ear, or in the ear 64. Three questions, adapted from the self-report form of the London Fibromyalgia Epidemiology Study Screening Questionnaire 66, were used to assess chronic widespread pain. Twins were asked whether or not they had experienced at least three months of body pain in: 1) shoulders, arms, or hands, 2) legs or feet, and 3) neck, chest, or back. Chronic widespread pain was defined as pain experienced in all three regions and bilateral sides of the body.

Overweight and obesity

Twins self-reported their height and weight. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the individuals' body weight in kilograms by the square of their height in meters. Overweight was defined as a BMI of 25.0 – 29.9 kg/m2 and obesity was defined as a BMI of ≥ 30.0 kg/m2. Twins who met criteria for being underweight were excluded from the study analyses because we wanted to compare overweight and obese twins to a comparison group of normal weight twins. Given the possibility of potentially significant medical problems associated with being underweight, the inclusion of underweight twins also may have introduced biases.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics for participant characteristics were calculated using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percents for categorical variables. Generalized estimating equation regression analyses, which account for the lack of independence of twins within a pair 18, 28, were used to examine differences on demographic and depression features by BMI status, and the association of pain diagnoses and symptoms with overweight and obesity.

We initially modeled the association between the pain diagnoses and symptoms and overweight and obesity in all twins by using generalized estimating equation regression models to account for clustering of twin data. Results are presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). We conducted stepwise analyses, where we first adjusted for age and gender, and then for depression to determine the additional contribution that depression would account for in these relationships.

A second set of regression analyses followed the initial modeling by examining the within-pair associations for pain diagnoses, pain symptoms, and overweight and obesity after adjusting for between-pair effects. Since twin pairs share a similar family environment and at least a portion of their genes (100% in monozygotic and on average 50% in dizygotic pairs), within-pair effects are adjusted for familial and some genetic influences because each individual is compared to his/her twin on outcome, predictor, and covariate measures. If the within-pair association between pain diagnoses and symptoms and overweight and obesity is attenuated and rendered non-significant compared to the overall effect obtained in our initial regression analyses, then we can conclude that familial and/or genetic factors contribute to these associations. Alternately, a within-pair association that remains robust compared to the overall effect provides evidence that familial/genetic factors play a small role in the association between pain diagnoses and symptoms and overweight and obesity. The within-pair analyses also were adjusted for age, gender, and depression. Further, Wald tests were used to statistically compare within- and between-pair estimates. A significant difference in these estimates would indicate that the overall estimate provided a poor fit to the data. Statistical significance level was set at 0.05. We used Stata/SE software, Version 9.0 for all statistical analyses 53.

Although twin samples are often associated with classical twin studies that quantify the relative contribution of genes and environment to individual phenotypes or the co-variation of multiple phenotypes, twins also offer the unique opportunity to address other questions of importance34. In this study, we chose to use the co-twin control design that controls for the effects of familial factors for 2 primary reasons. First, we had multiple pain phenotypes, therefore an adequately powered multivariate genetic analysis would require a substantially larger sample. Second, the pain phenotypes were based on self-report and not all were well-characterized. Thus, the co-twin control design was the more conservative approach as a first step in examining the familial influences on chronic pain and overweight and obesity.

RESULTS

Of the 4,824 individual twins enrolled in the registry, 1,004 were excluded because they had a twin of the opposite sex, and 175 were underweight. Of the remaining 3,645 individual twins, 3,471 had complete date available for all study variables were included in the analyses. The average BMI of the entire sample was 24.8 kg/m2 (standard deviation [SD] = 4.8 kg/m2). Among all twins, 62.5% (n = 2169) were normal weight, 24.3% (n = 842) were overweight, and 13.3% (n = 460) were obese.

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the sample stratified by BMI. Among all twins, the mean age was 31 years, 62% were female, 40% were married or living with a partner, 86% were White, 89% had finished high school or above, and 66% were monozygotic. Depression was reported by 19% of all twins. The sample was representative of the Washington state population demographics. Obese twins were older (p < 0.001), more depressed (p < 0.001), and more likely to be dizygotic (p < 0.01), living with a partner (p < 0.001), and have less education (p < 0.01) than twins of normal weight. Race or education did not differ based on weight. Overweight twins were also more likely to be male (p < 0.001), living with a partner (p < 0.001), and older (p < 0.001) than normal weight twins.

Table 1.

Characteristics for the University of Washington Twin Registry sample by BMI status.

| BMI |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Normal (N = 2,169) | Overweight (n = 842) | Obese (n = 460) |

| Demographic | |||

| Monozygotic, % | 68 | 65 | 58 |

| Age, mean years ± SD | 28 ± 13 | 35 ± 15 | 38 ± 15 |

| Female, % | 65 | 51 | 66 |

| Married or living with a partner, % | 33 | 51 | 55 |

| White, % | 86 | 88 | 84 |

| ≥ High school education, % | 90 | 90 | 87 |

| Depression, % | 17 | 20 | 29 |

BMI = body mass index; SD = standard deviation.

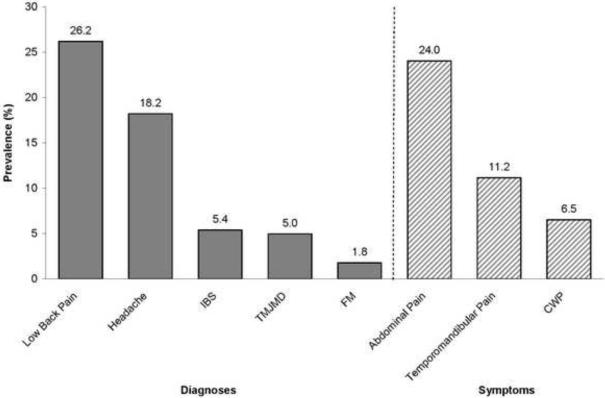

Figure 1 depicts the prevalence of chronic pain diagnoses and symptoms for all twins. Low back pain (26%) and tension-type or migraine headache (18%) were the two most common pain diagnoses. Additionally, 24% of all twins reported symptoms of abdominal pain, 11% reported temporomandibular pain, and close to 7% had symptoms of chronic widespread pain.

Figure 1. Prevalence of pain diagnoses and symptoms.

IBS = irritable bowel syndrome; TMJMD = temporomandibular joint or muscle disorder; FM = fibromyalgia; CWP = chronic widespread pain.

Table 2 presents ORs and 95% CIs for the overall associations between pain diagnoses and symptoms, and overweight and obesity adjusting for age and gender. These analyses revealed significant associations of low back pain and abdominal pain for the overweight and obese groups. There was also a significant association of temporomandibular joint or muscle disorder for the overweight group. Additional associations were found for headache, fibromyalgia, and chronic widespread pain for the obese group only. Compared with normal weight twins, overweight or obese twins were 1.3 – 3.0 times more likely to report these pain diagnoses and symptoms.

Table 2.

Associations between lifetime chronic pain diagnoses and pain symptoms, and overweight and obesity, adjusted for age and gender.

| Overweight vs. Normal |

Obese vs. Normal |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Diagnoses | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Low Back Pain | 1.55 | 1.28–1.87 | 2.11 | 1.67–2.67 |

| Tension-type or Migraine Headache | 1.16 | 0.92–1.46 | 1.70 | 1.32–2.19 |

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome | 0.86 | 0.58–1.28 | 1.44 | 0.96–2.16 |

| Temporomandibular joint or muscle disorder | 1.49 | 1.03–2.17 | 1.45 | 0.95–2.17 |

| Fibromyalgia | 0.92 | 0.46–1.84 | 2.31 | 1.21–4.42 |

| Pain Symptoms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal Pain | 1.45 | 1.14–1.85 | 1.30 | 1.07–1.58 |

| Temporomandibular joint or muscle pain |

1.31 | 0.96–1.79 | 1.13 | 0.87–1.48 |

| Chronic Widespread Pain | 3.02 | 2.14–4.25 | 1.11 | 0.77–1.58 |

Results based on generalized estimating equation regression analyses. Significant associations are emboldened.

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Table 3 presents ORs and 95% CIs for the overall associations between pain diagnoses and symptoms, and overweight and obesity after adjusting for age, gender, and depression to determine if depression partially explained these relationships. After this adjustment, all of the associations were diminished; however, the majority of the associations remained significant. Specifically, low back pain and abdominal pain remained associated with both overweight and obesity. Headache, fibromyalgia, and chronic widespread pain remained significantly associated with obesity alone. The relationship between temporomandibular joint or muscle disorder and being overweight was no longer significant.

Table 3.

Associations between lifetime chronic pain diagnoses and pain symptoms, and overweight and obesity, adjusted for age, gender, and depression.

| Overweight vs. Normal |

Obese vs. Normal |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Diagnoses | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Low Back Pain | 1.51 | 1.25–1.84 | 1.94 | 1.53–2.46 |

| Tension-type or Migraine Headache | 1.11 | 0.89–1.40 | 1.54 | 1.18–1.99 |

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome | 0.80 | 0.53–1.21 | 1.20 | 0.79–1.81 |

| Temporomandibular joint or muscle disorder | 1.44 | 0.99–2.09 | 1.25 | 0.82–1.92 |

| Fibromyalgia | 0.89 | 0.44–1.79 | 2.03 | 1.06–3.90 |

| Pain Symptoms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal Pain | 1.34 | 1.05–1.71 | 1.27 | 1.04–1.55 |

| Temporomandibular joint or muscle pain |

1.18 | 0.86–1.62 | 1.08 | 0.84–1.42 |

| Chronic Widespread Pain | 2.71 | 1.92–3.83 | 1.06 | 0.74–1.52 |

Results based on generalized estimating equation regression analyses. Significant associations are emboldened.

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Table 4 displays the adjusted ORs and 95% CIs for the within-pair associations between pain diagnoses and symptoms and overweight and obesity. Within-pair analyses adjust for the effects of familial factors and, in addition, these results are adjusted for age, gender, and depression. With this adjustment, all of the associations were further diminished. Low back pain and chronic widespread pain were the only two pain conditions that remained significantly associated with obesity. Compared to normal weight twins, obese twins were twice as likely to report symptoms of chronic widespread pain and were 1.6 times as likely to have low back pain. No other pain diagnoses or symptoms remained significant after adjusting for the effects of age, gender, depression, and familial factors.

Table 4.

Adjusted1 within-pair associations between lifetime chronic pain diagnoses and pain symptoms, and overweight and obesity.

| Overweight vs. Normal Within-pair |

Obese vs. Normal Within-pair |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Diagnoses | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI |

| Low Back Pain | 1.16 | 0.83–1.62 | 1.60 | 1.01–2.53 |

| Tension-type or Migraine Headache | 0.87 | 0.59–1.29 | 1.21 | 0.73–2.00 |

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome | 0.95 | 0.46–1.94 | 1.85 | 0.72–4.78 |

| Temporomandibular joint or muscle disorder | 1.13 | 0.58–2.19 | 1.95 | 0.85–4.51 |

| Fibromyalgia | 0.74 | 0.24–2.26 | 1.13 | 0.32–4.03 |

| Pain Symptoms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal Pain | 1.08 | 0.71–1.63 | 1.09 | 0.80–1.50 |

| Temporomandibular joint or muscle pain |

1.10 | 0.57–2.13 | 1.04 | 0.64–1.68 |

| Chronic Widespread Pain | 2.35 | 1.14–4.87 | 0.68 | 0.37–1.23 |

Adjusted for age, gender, and depression.

Results based on generalized estimating equation regression analyses. Significant associations are emboldened.

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

We found that twins who were overweight or obese were more likely to report physician-diagnosed low back pain, tension-type or migraine headache, fibromyalgia, and symptoms of abdominal pain and chronic widespread pain than normal weight twins. These findings support previous reports linking pain and obesity in both clinical and community samples 45, 67, 69. However, all relationships were diminished after adjustment for depression, indicating that depression may contribute to the association between higher BMI and pain symptoms. We also found evidence that familial factors, either genetic or shared environmental risk factors, may play a role in the relationship of both overweight and obesity and pain disorders and symptoms.

Few twin studies have examined the associations between pain conditions and obesity. Our results are unique in that our co-twin control method allowed us to control for shared familial and genetic factors. Although we found no significant differences in the within- and between-pair estimates, there was a consistent pattern of attenuated associations of within-pair estimates compared to the overall estimates for all chronic pain diagnoses and symptoms and overweight and obesity, suggesting that familial and genetic influences may partially explain these relationships. These results are consistent with a previous twin study demonstrating a genetic influence on the relationship between low back pain and obesity 36 and research on the genetic basis of obesity and chronic pain independently. Obesity is a strongly genetic trait, with heritability estimates ranging from 50 – 80% in twin studies 48. Genetic influences have also been reported for most of the pain diagnoses and symptoms examined in this study, with heritability estimates ranging from 25% for irritable bowel syndrome to 45% for fibromyalgia, and up to 68% for back pain 5, 11, 17, 38, 40, 43, 44, 51, 55.

The unexpected finding that dizygotic twins in this study were more likely to be obese compared to normal weight twins is contrary to prior heritability studies and deserves further exploration. We also found that the dyzygotic twins were significantly older than the monozygotic twins (p < .01). Given the known association between age and obesity65, this may account for the surprising findings. Nonetheless, these unexpected findings should not have any implications for the primary study findings. The mechanisms underlying the relationship between chronic pain conditions and overweight or obesity remain unclear but are likely diverse and multifactorial. For example, knee and back pain have been associated with structural mechanisms 33, 35, chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia have been shown to be associated with metabolic pathways 39, whereas low back pain has been related to behavioral processes 62. In addition, there are some findings to suggest that environmental factors may have a greater impact on the link between some pain conditions and obesity than genetic influences 19, 41.

The modest but significant associations between temporomandibular joint or muscle disorder and being overweight did not persist after further adjusting for depression suggesting that depression may play a substantial role in the observed relationship. This is not surprising given the established associations between depression and pain as well as depression and obesity4, 10, 42 and the plausibility that depression could exacerbate both conditions. However, it is interesting that depression seemed to have more of an impact on temporomandibular joint or muscle disorder compared to the other pain diagnoses and symptoms. Depression may play a larger role in the development of this pain condition and increased weight in this population 20, 67.

Alternatively, metabolic syndrome, a condition characterized by abdominal obesity, metabolic disturbances, and associated stress system dysregulation, has been associated with chronic pain conditions and may be genetically influenced 24, 39, 57, perhaps through chronic inflammation, which occurs with metabolic syndrome, obesity, and many pain conditions 12, 22, 63. Chronic inflammatory states also have been linked to major depression 22. This association with the stress response and inflammation may help to explain the relationship that we see between overweight and obesity, and pain conditions commonly associated with stress, such as headache and abdominal pain 9, 15. The complex relationships between chronic pain conditions, obesity, metabolic and inflammatory processes, and familial and genetic factors are worthy of further scientific inquiry.

Behavioral factors also have been implicated in the etiology and maintenance of pain and obesity 62. In this regard, inactivity and a sedentary lifestyle can lead to obesity, which contributes to transforming acute pain into chronic pain. Pain can decrease physical activity, leading to weight gain. Alternately, a sedentary lifestyle associated with pain and obesity may be caused by a common factor. For example, depressed individuals may withdraw from activities and have sedentary lifestyles, potentially leading to comorbid chronic pain and obesity. Our finding that depression is related to some of the associations between pain conditions, and overweight and obesity, is congruent with this hypothesis. Behavioral factors also may play a prominent role the relationship of obesity with low back pain and chronic widespread pain, the only two associations that remained significant after controlling for familial factors. Chronic widespread pain and low back pain have both been linked to behavioral factors, such as physical inactivity and stress, and tend to show improvements when treated with a combination of physical exercise and stress management or cognitive behavioral therapy 6, 31. Taken together, this diverse literature underscores that the relationship between chronic pain, and overweight and obesity results from the confluence of environmental, familial and genetic, structural, metabolic, and behavioral pathways.

This study had several limitations. First, the use of self-report of a physician diagnosis of chronic pain conditions is sub-optimal and we cannot determine how the rates of these conditions might compare to actual clinical assessments. In addition, symptomatic individuals who have not been formally diagnosed or have limited access to healthcare were not accounted for in these analyses. However, physician-diagnoses are less likely to be false positives; therefore our findings are likely conservative estimates. A related caveat is that the use of low back pain as a diagnosis may be a source of error as low back pain is not a formal physician-diagnosed condition and is often thought of as a symptom. However, the rates of low back pain, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, headache, and temporomandibular joint or muscle disorder were consistent with those of other population-based studies 3, 21, 47, 54, 68. Second, BMI may have been underestimated due to self-report of weight and height, resulting in misclassification and possibly in attenuation of the effect sizes. Third, the conditions assessed were based on different time scales (i.e., pain and depression were lifetime diagnoses and pain symptoms were assessed for the last three months). Therefore, we were not able to examine if two or more pain conditions or symptoms were experienced at that the same time, which may attenuate the estimated associations found in this study. Fourth, our sample was predominately White, female, and educated, thus limiting the generalizability of our findings to other populations and may have also impacted the lower overweight and obesity rates seen in this study compared to the general population. Further, the lower rates of overweight and obesity may have attenuated the associations between chronic pain, and overweight and obesity. Finally, ethnicity was not included as a covariate in the analyses and may lead to overestimation of familial effects given that Whites may experience different environments based on their ethnicity.

In sum, in our large community-based sample of twins we found that overweight and obesity were consistently related to diagnoses of low back pain, tension-type or migraine headache, and fibromyalgia, and symptoms of abdominal pain and chronic widespread pain. Depression was shown to contribute to the link between these pain conditions, and overweight and obesity. In addition, these relationships were partially explained by familial influences. Our findings highlight that several mechanisms underlie the co-occurrence of chronic pain, and overweight and obesity. Regardless of the causal underpinnings, chronic pain, and overweight and obesity likely have additive effects, resulting in decreased health-related quality of life and increased disability 23, 25, 42. It is, therefore, critical that interventions effectively address both of these increasingly prevalent conditions. Future longitudinal research should assess genetic, environmental, metabolic, structural, and behavioral mechanisms that explain the link between chronic pain, and overweight and obesity to inform appropriate evidence-based interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health awards R01AR051524 (Dr. Afari) AND 5 U19 AI38429 (Dr. Buchwald). Drs. Afari and Buchwald also are supported by National Institutes of Health award U01 DK082325. Dr. Afari is supported in part by the VA Center of Excellence for Stress and Mental Health. Dr. Johnson Wright is supported in part by R01AR051524. Dr. Schur is supported by K23 DK070826. We are gratefully indebted to the twins who take part in the University of Washington Twin Registry for their time and enthusiasm.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

PERSPECTIVE This article reports on the familial contribution and the role of psychological factors in the relationship between chronic pain, and overweight and obesity. These findings can increase our understanding of the mechanisms underlying these two commonly comorbid sets of conditions.

References

- 1.Afari N, Noonan C, Goldberg J, Edwards K, Gadepalli K, Osterman B, Evanoff C, Buchwald D. University of Washington Twin Registry: construction and characteristics of a community-based twin registry. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9:1023–1029. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson JP, Kaplan RM, Ake CF. Arthritis impact on U.S. life quality: Morbidity and mortality effects from National Health Survey Data 1986–1988 and 1994 using QWBX1 estimates of well-being. Social Indicators Research. 2004;69:67–91. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrews EB, Eaton SC, Hollis KA, Hopkins JS, Ameen V, Hamm LR, Cook SF, Tennis P, Mangel AW. Prevalence and demographics of irritable bowel syndrome: results from a large web-based survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:935–942. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnow BA, Hunkeler EM, Blasey CM, Lee J, Constantino MJ, Fireman B, Kraemer HC, Dea R, Robinson R, Hayward C. Comorbid depression, chronic pain, and disability in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:262–268. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000204851.15499.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bengtson MB, Ronning T, Vatn MH, Harris JR. Irritable bowel syndrome in twins: genes and environment. Gut. 2006;55:1754–1759. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.097287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergman S. Management of musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bigal ME, Gironda M, Tepper SJ, Feleppa M, Rapoport AM, Sheftell FD, Lipton RB. Headache prevention outcome and body mass index. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:445–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bigal ME, Liberman JN, Lipton RB. Obesity and migraine: a population study. Neurology. 2006;66:545–550. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000197218.05284.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bigal ME, Tsang A, Loder E, Serrano D, Reed ML, Lipton RB. Body mass index and episodic headaches: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1964–1970. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.18.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blaine B. Does Depression Cause Obesity?: A Meta-analysis of Longitudinal Studies of Depression and Weight Control. J Health Psychol. 2008;13:1190–1197. doi: 10.1177/1359105308095977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buskila D, Sarzi-Puttini P, Ablin JN. The genetics of fibromyalgia syndrome. Pharmacogenomics. 2007;8:67–74. doi: 10.2217/14622416.8.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chrousos GP. Stress, chronic inflammation, and emotional and physical well-being: concurrent effects and chronic sequelae. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:S275–291. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.110163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chrousos GP, Kino T. Glucocorticoid action networks and complex psychiatric and/or somatic disorders. Stress. 2007;10:213–219. doi: 10.1080/10253890701292119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark DO, Mungai SM. Distribution and association of chronic disease and mobility difficulty across four body mass index categories of African-American women. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:865–875. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M, Garcia MA, Burton D, Busciglio I. High body mass alters colonic sensory-motor function and transit in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G382–388. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90286.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delgado-Aros S, Locke GR, 3rd, Camilleri M, Talley NJ, Fett S, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Obesity is associated with increased risk of gastrointestinal symptoms: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1801–1806. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diatchenko L, Slade GD, Nackley AG, Bhalang K, Sigurdsson A, Belfer I, Goldman D, Xu K, Shabalina SA, Shagin D, Max MB, Makarov SS, Maixner W. Genetic basis for individual variations in pain perception and the development of a chronic pain condition. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:135–143. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford University Press Inc.; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding C, Cicuttini F, Blizzard L, Jones G. Genetic mechanisms of knee osteoarthritis: a population-based longitudinal study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R8. doi: 10.1186/ar1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drangsholt MT. Psychological characteristics such as depression, independent from a known genetic risk factor, increase the risk of developing temporomandibular disorder pain. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2008;8:240–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dworkin SF, Huggins KH, LeResche L, Von Korff M, Howard J, Truelove E, Sommers E. Epidemiology of signs and symptoms in temporomandibular disorders: clinical signs in cases and controls. J Am Dent Assoc. 1990;120:273–281. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1990.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elenkov IJ, Iezzoni DG, Daly A, Harris AG, Chrousos GP. Cytokine dysregulation, inflammation and well-being. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2005;12:255–269. doi: 10.1159/000087104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ettinger WH, Davis MA, Neuhaus JM, Mallon KP. Long-term physical functioning in persons with knee osteoarthritis from NHACNES. I: Effects of comorbid medical conditions. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:809–815. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Expert Panel on Detection E. Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fanuele JC, Abdu WA, Hanscom B, Weinstein JN. Association between obesity and functional status in patients with spine disease. Spine. 2002;27:306–312. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200202010-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finkelstein EA, Fiebelkorn IC, Wang G. State-level estimates of annual medical expenditures attributable to obesity. Obes Res. 2004;12:18–24. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gatchel RJ. Comorbidity of chronic pain and mental health disorders: the biopsychosocial perspective. Am Psychol. 2004;59:795–805. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldstein H. Multilevel Statistical Models. Halstead Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gureje O, Von Korff M, Simon GE, Gater R. Persistent pain and well-being: a World Health Organization Study in Primary Care. Jama. 1998;280:147–151. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardt J, Jacobsen C, Goldberg J, Nickel R, Buchwald D. Prevalence of chronic pain in a representative sample in the United States. Pain Med. 2008;9:803–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holth HS, Werpen HK, Zwart JA, Hagen K. Physical inactivity is associated with chronic musculoskeletal complaints 11 years later: results from the Nord-Trondelag Health Study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:159. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janke EA, Collins A, Kozak AT. Overview of the relationship between pain and obesity: What do we know? Where do we go next? J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44:245–262. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2006.06.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jinks C, Jordan KP, Blagojevic M, Croft P. Predictors of onset and progression of knee pain in adults living in the community. A prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:368–374. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson W, Turkheimer E, Gottesman II, Bouchard TJ. Beyond heritability: Twin studies in behavioral research. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18:217–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lake JK, Power C, Cole TJ. Back pain and obesity in the 1958 British birth cohort. cause or effect? J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:245–250. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO, Bruun NH. Low back pain and lifestyle. Part II--Obesity. Information from a population-based sample of 29,424 twin subjects. Spine. 1999;24:779–783. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199904150-00009. discussion 783-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lementowski PW, Zelicof SB. Obesity and osteoarthritis. Am J Orthop. 2008;37:148–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Limer KL, Nicholl BI, Thomson W, McBeth J. Exploring the genetic susceptibility of chronic widespread pain: the tender points in genetic association studies. Rheumatology (Oxford) in. 2008;47:572–577. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loevinger BL, Muller D, Alonso C, Coe CL. Metabolic syndrome in women with chronic pain. Metabolism. 2007;56:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacGregor AJ, Andrew T, Sambrook PN, Spector TD. Structural, psychological, and genetic influences on low back and neck pain: a study of adult female twins. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:160–167. doi: 10.1002/art.20236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manek NJ, Hart D, Spector TD, MacGregor AJ. The association of body mass index and osteoarthritis of the knee joint: an examination of genetic and environmental influences. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:1024–1029. doi: 10.1002/art.10884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marcus DA. Obesity and the impact of chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:186–191. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200405000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Markkula R, Jarvinen P, Leino-Arjas P, Koskenvuo M, Kalso E, Kaprio J. Clustering of symptoms associated with fibromyalgia in a Finnish Twin Cohort. Eur J Pain. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mulder EJ, Van Baal C, Gaist D, Kallela M, Kaprio J, Svensson DA, Nyholt DR, Martin NG, MacGregor AJ, Cherkas LF, Boomsma DI, Palotie A. Genetic and environmental influences on migraine: a twin study across six countries. Twin Res. 2003;6:422–431. doi: 10.1375/136905203770326420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neumann L, Lerner E, Glazer Y, Bolotin A, Shefer A, Buskila D. A cross-sectional study of the relationship between body mass index and clinical characteristics, tenderness measures, quality of life, and physical functioning in fibromyalgia patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:1543–1547. doi: 10.1007/s10067-008-0966-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. Jama. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papageorgiou AC, Croft PR, Ferry S, Jayson MI, Silman AJ. Estimating the prevalence of low back pain in the general population. Evidence from the South Manchester Back Pain Survey. Spine. 1995;20:1889–1894. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199509000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perusse L. Genetics of human obesity: results from genetic epidemiology studies. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2000;61(Suppl 6):24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramsey F, Ussery-Hall A, Garcia D, McDonald G, Easton A, Kambon M, Balluz L, Garvin W, Vigeant J. Prevalence of selected risk behaviors and chronic diseases--Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), 39 steps communities, United States, 2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reed T, Plassman BL, Tanner CM, Dick DM, Rinehart SA, Nichols WC. Verification of self-report of zygosity determined via DNA testing in a subset of the NAS-NRC twin registry 40 years later. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2005;8:362–367. doi: 10.1375/1832427054936763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Russell MB, Levi N, Kaprio J. Genetics of tension-type headache: a population based twin study. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:982–986. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scher AI, Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Lipton RB. Factors associated with the onset and remission of chronic daily headache in a population-based study. Pain. 2003;106:81–89. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software: Release 9. StataCorp LP; College Station, TX: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strine TW, Chapman DP, Balluz LS. Population-based U.S. study of severe headaches in adults: psychological distress and comorbidities. Headache. 2006;46:223–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Svedberg P, Johansson S, Wallander MA, Pedersen NL. No evidence of sex differences in heritability of irritable bowel syndrome in Swedish twins. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2008;11:197–203. doi: 10.1375/twin.11.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Talley NJ, Howell S, Poulton R. Obesity and chronic gastrointestinal tract symptoms in young adults: a birth cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1807–1814. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Teran-Garcia M, Bouchard C. Genetics of the metabolic syndrome. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2007;32:89–114. doi: 10.1139/h06-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thompson WG, Creed FH, Drossman DA, Heeton KW, Kruis W. Functional bowel disorders and chronic functional abdominal pain. Gastroenterology International. 1992;5:75–91. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Irvine EJ, Muller-Lissner SA. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. 1999;45(Suppl 2):II43–47. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Torgersen S. The determination of twin zygosity by means of a mailed questionnaire. Acta Genet Med Gemellol (Roma) 1979;28:225–236. doi: 10.1017/s0001566000009077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tukker A, Visscher T, Picavet H. Overweight and health problems of the lower extremities: osteoarthritis, pain and disability. Public Health Nutr. 2008:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Verbunt JA, Seelen HA, Vlaeyen JW, van de Heijden GJ, Heuts PH, Pons K, Knottnerus JA. Disuse and deconditioning in chronic low back pain: concepts and hypotheses on contributing mechanisms. Eur J Pain. 2003;7:9–21. doi: 10.1016/s1090-3801(02)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vgontzas AN, Bixler EO, Papanicolaou DA, Chrousos GP. Chronic systemic inflammation in overweight and obese adults. Jama. 2000;283:2235. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.17.2235. author reply 2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Von Korff M, Dworkin SF, Le Resche L, Kruger A. An epidemiologic comparison of pain complaints. Pain. 1988;32:173–183. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States--gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.White KP, Harth M, Speechley M, Ostbye T. Testing an instrument to screen for fibromyalgia syndrome in general population studies: the London Fibromyalgia Epidemiology Study Screening Questionnaire. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:880–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wolfe F, Hawley DJ. Psychosocial factors and the fibromyalgia syndrome. Z Rheumatol. 1998;57(Suppl 2):88–91. doi: 10.1007/s003930050243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, Russell IJ, Hebert L. The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:19–28. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yunus MB, Arslan S, Aldag JC. Relationship between body mass index and fibromyalgia features. Scand J Rheumatol. 2002;31:27–31. doi: 10.1080/030097402317255336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]