Abstract

Background

Safety and efficacy limit currently available atrial fibrillation (AF) therapies. We hypothesized that atrial gene transfer would allow focal manipulation of atrial electrophysiology, and by eliminating reentry, would prevent AF.

Methods and results

In a porcine AF model, we compared control animals to animals receiving adenovirus encoding KCNH2-G628S, a dominant negative mutant of the IKr potassium channel α-subunit, (G628S animals). After epicardial atrial gene transfer and pacemaker implantation for burst atrial pacing, animals were evaluated daily for cardiac rhythm. Electrophysiological and molecular studies were performed at baseline and at sacrifice on either post-operative day 7 or 21. By day 10, none of the control animals and all of the G628S animals were in sinus rhythm. After day 10, the percentage of G628S animals in sinus rhythm gradually deteriorated until all animals were in AF by day 21. The relative risk of AF throughout the study was 0.44 (95% CI 0.33-0.59, p < 0.01) among the G628 group vs. controls. Atrial monophasic action potential was considerably longer in G628S animals compared to controls at day 7, and KCNH2 protein levels were 61% higher in the G628S group compared to control animals (p<0.01). Loss of gene expression at day 21 correlated with loss of action potential prolongation and therapeutic efficacy.

Conclusions

Gene therapy with KCNH2-G628S eliminated AF by prolonging atrial action potential duration. The effect duration correlated with transgene expression.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, gene therapy, ion channels, electrophysiology, arrhythmia

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia, affecting 2-5 million people in the United States and several million more worldwide.1, 2 The presence of AF increases mortality risk 1.9-fold and stroke risk 5-fold. AF has a complex interaction with heart failure, with each increasing the probability and severity of the other.3 Safety and efficacy limit currently available AF therapies. The best antiarrhythmic drugs allow AF recurrence in over 50% of patients within one year of therapy initiation.4 Toxicities frequently limit antiarrhythmic use, most notably ventricular arrhythmias in up to 5% of patients.5 Percutaneous, endocardial radiofrequency ablation can eliminate AF in a limited subset of patients, but recurrences are frequent and the procedure is highly complex, time intensive, and carries substantial risk for complications including pulmonary vein stenosis, atrial-esophageal fistula, cardiac tamponade, stroke and death.6 The Cox-Maze procedure is a curative but extremely invasive surgical option.7 Epicardial approaches using radiofrequency or ultrasound ablation to reduce the invasive nature of the Cox procedure are under development, but there is limited experience regarding safety and long-term results for these techniques.8 Therefore, molecular therapies for AF that could overcome the limitations of current treatment options may be highly desirable.

An important first step for developing AF therapies is consideration of the arrhythmia mechanism. Extensive investigation in a number of labs has shown that the underlying mechanism for AF includes triggering events that start the arrhythmia and maintenance conditions that sustain the rhythm (for more thorough review, see Nattel.9). Triggers generally are single or repetitive atrial premature beats that occur when afterdepolarizations in individual cells spread throughout the atria. A variety of mechanisms can sustain AF, including continuation of the triggering afterdepolarizations and either focal or broad reentrant electrical circuits. Conditions that allow electrical reentry in the myocardium are essentially conditions that allow the cells within the circuit to recover in the interval between one beat and the next, e.g. short cellular refractory period, slow conduction velocity, or focal conduction block.

We hypothesized that lengthening atrial action potential duration (APD) would disrupt intra-atrial reentry and thereby terminate fibrillation. We addressed this hypothesis in a porcine model of burst pacing-induced AF with gene transfer of KCNH2-G628S, a dominant negative mutant of the IKr α-subunit, using our previously reported atrial painting method that allows 100% transmural gene transfer.10, 11 Zhou et al. showed that gene transfer with this mutant causes normal expression, post-translational processing and membrane localization of the ion channel, and that it disrupts IKr by blocking the channel pore.12 Here, we test the ability of gene transfer using this mutation to prolong atrial APD and prevent AF.

Methods

Adenovirus vectors

Adβgal contained the Escherichia coli lacZ gene driven by the human cytomegalovirus immediate/early promoter. AdG628S contained the KCNH2-G628S gene driven by the human cytomegalovirus immediate/early promoter. Virus construction, expansion and quality control have been previously described.11

Pacemaker implantation, gene transfer, and pacing protocol

Prior to starting the procedure, the infection solution was made by chilling Krebs' solution to 4° C and slowly adding poloxamer F127 (BASF Corporation, Mt. Olive, NJ). Immediately before use, adenovirus and trypsin stock solutions were added to the poloxamer/Krebs' solution for a final virus concentration of 1 × 109 pfu/ml, final poloxamer concentration of 20% (w/v) and a final trypsin concentration of 0.5% (w/v). After complete mixing, the solution was warmed at 37° C to achieve a firm gel consistency.

Twenty-seven Yorkshire pigs weighing 20-30 kg were used. After sedation (telazol 1.5mg/kg IM, xylazine 1.5mg/Kg IM, and ketamine 1.5mg/kg IM), induction of anesthesia (isoflurane 0.5-1.5%) and sterile preparation, the right internal jugular vein was accessed by cut-down. An active-fixation lead was placed in the right atrium under fluoroscopic guidance. Adequate pacing parameters (electrogram > 1.5 mV, pacing threshold < 1 V) were confirmed and the lead was securely tied to the vein. The atrial lead was connected to a Medtronic pacemaker, and the system was placed in a subcutaneous pocket in the neck.

After closing the pacemaker pocket, the chest was opened by median sternotomy. The pericardium was incised. Invasive EP study was performed as described below. After EP study, the gene painting procedure was performed. The virus/trypsin/poloxamer gel was painted onto the atria using a rounded bristle, flat paintbrush composed of camel hair. The heart was manipulated to paint every accessible area of the atrial epicardium. Each atrium was coated twice for 60 seconds each, and approximately 5 minutes were given between painting coats to allow absorption. After painting, the heart was left exposed to air for 10 minutes to allow virus penetration. After the chest was closed, the pacemaker was programmed to burst pace the right atrium at 42 Hz frequency and 7.5 V output for 2 second increments alternating with 2 second pauses between burst episodes.

Animals receiving AdG628S (G628S animals, n = 7) were compared to animals receiving Adβgal (virus control, n = 5) and animals who underwent the same painting protocol without virus (no virus control, n = 5). In order to assess the electrophysiological and molecular properties, at peak gene effect, 5 more animals receiving AdG628S and 5 more control animals were studied in a 7-day protocol.

The animals for this study were maintained in accordance with Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals from the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare, National Institutes of Health. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Electrophysiological studies and rhythm evaluation at follow up

Immediately before and 7 or 21 days after gene transfer, the animals underwent open-chest electrophysiology (EP) study. Animals in AF were cardioverted to sinus rhythm (SR) for EP study. Conventional 12-lead ECG was recorded with standard lead positions. Monophasic action potential (MAP) recordings were assessed from the epicardial wall under direct visualization to reproduce the locations. MAPs were acquired in digital format (EP Medical Systems, New Berlin, NJ), using a 7-French MAP catheter (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA). The MAP catheter was positioned at the center of 10 pre-defined epicardial atrial regions and in the basal region of the ventricles, adjacent to atrial sites 4 and 9. Please see Kikuchi et al. (available free online at http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/reprint/111/3/264) for a schematic of the MAP sites.11 The MAP duration was measured as the interval from the steepest part of the MAP upstroke to the level of 90% repolarization (MAPD90) during regular pacing with a drive train cycle length of 400 ms.

In the 7-day experiments, in addition to the MAP recordings, the atrial conduction time was measured by placement of epicardial catheters at the sinus node, left and right atrial appendage regions. Conduction time to left and right atrial appendages was measured while pacing the sinus node region at a drive cycle length of 400 ms. Pan-atrial conduction time was measured by pacing the right atrial appendage at a 400 ms drive cycle length while recording from the left atrial appendage.

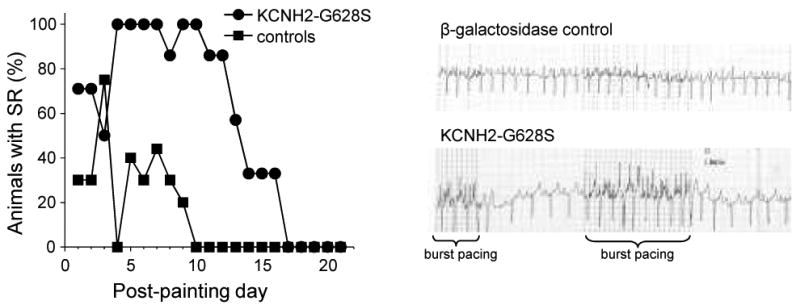

Continuous rhythm monitoring was not available. Daily rhythm monitoring was obtained by ECG recordings that were performed on a daily basis using a 6 lead ECG system. Animals were awake and alert at consistent levels from one reading to the next. The rhythm during the 2-seconds off-pacing windows was assessed over a 2 minute recording. Animals were considered to have SR if sinus beats were detected during the recording interval and AF if all windows showed AF (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Rhythm on daily telemetry as a function of time since gene transfer. The left panel shows that control animals (N=10) continually progress toward persistent AF after initiation of burst atrial pacing, whereas the G628S animals (N=7) show an abrupt increase in percent with sinus rhythm 3 days after gene transfer, correlating with onset of gene expression. G628S animals maintained sinus rhythm until days 11-18, correlating with the time that gene expression is lost. The right panel shows examples of telemetry recordings from animals 8 days after gene transfer.

Western Blot

The animals were sacrificed after the follow-up EP study. The atria were dissected free from the ventricles and frozen in liquid nitrogen for later analysis. To quantify protein content of tissue extracts, Western blot analysis was performed on proteins extracted from the frozen tissue samples. The concentrations of proteins were determined by the BCA method (Pierce Chemical). Proteins were fractionated by 4-12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking with 5% non fat dry milk membrane, membranes were blotted with anti-KCNH2 C-20 (polyclonal goat IgG diluted 1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and anti-GAPDH (polyclonal goat IgG diluted 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and a secondary antibody directed against the primary and conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (donkey anti-Goat IgG, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Bands were detected with the enhanced chemiluminescence assay (GE Healthcare) and quantified using the Image Quant software package (NIH).

Statistical analysis

Given our previous demonstration that lacZ gene transfer causes no electrophysiological effects,13-15 we prospectively combined the two control groups for statistical analysis. Due to the sample size continuous parameters are compared using the Mann-Whitney U non-parametric test, considering p<0.05 as significant. Data are presented as median with minimum and maximum observed values. As for the risk of persistent AF over time; because each animal was assessed more than once, In order to compensate for repeated measurements, the risk of atrial fibrillation over time was assessed using a generalized estimating equations (GEE) model (Poisson distribution) to address animal-level clustering, with a dependent variable of having AF at any given day.

Results

Rhythm analysis

We compared response to therapy between 7 AdG628S animals and 10 control animals (5 receiving no virus and 5 receiving Adβgal, encoding lacZ a protein that we have previously shown to have no detectible electrophysiological effects).13-15 At baseline, all animals underwent open-chest EP study, atrial pacemaker insertion and atrial painting of a gel containing 20% poloxamer, 0.5% trypsin, 1 × 109 pfu/ml of the indicated virus. In the case of the no virus controls, the painting solution contained only poloxamer and trypsin. Immediately after closing the chest in each animal, we activated the burst protocol to pace the atria at 42 Hz frequency for 2 second increments alternating with 2 second no pacing increments. We followed the animals with daily telemetry recordings that were performed in the unsedated, normally active state. Burst pacing was continued through the telemetry recordings, and we analyzed the 2 second no-pacing increments for rhythm analysis.

Immediately after initiation of the pacing protocol (days 1-3), the control and G628S groups had a similar percentage of animals in SR. Among the controls, the proportion of animals in sinus rhythm decreased progressively, until none had SR on or after day 10 (all in AF at that point). In contrast, the number of animals in SR increased abruptly on day 4 for the G628S animals, all G628S animals were in SR for days 4-10, except one G628S animal was in AF on day 8. That animal returned to sinus rhythm on day 9. After day 10, the number of G628S animals in SR gradually deteriorated until all animals were in AF by day 21.

Statistical analysis using a GEE model showed that the G628 group had significantly less risk of atrial fibrillation. (relative risk of AF = 0.44,95% CI=0.33-0.59, p < 0.01). Interestingly, the median time from onset of burst pacing to persistent AF for the control group in this study (5 days) was the same as our previously published result with the model,10 and the time from gene transfer to therapeutic effect in the treatment group was similar to previous observations for atrioventricular nodal gene therapy with this model.14

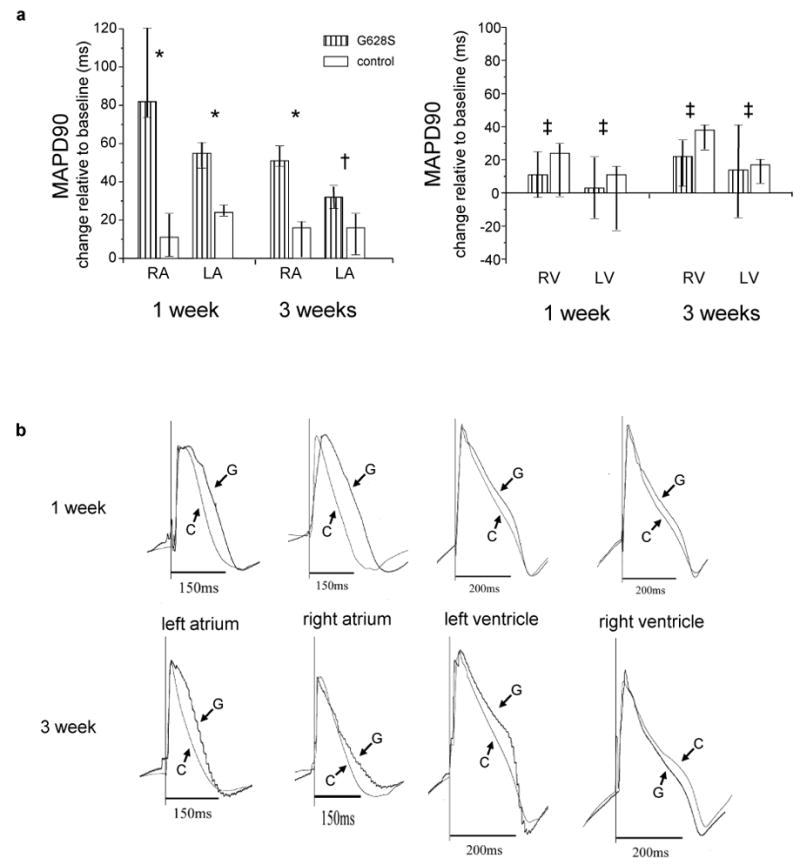

Effect on atrial action potential

To understand the mechanism underlying this successful intervention, invasive EP study was performed at termination of the in-life phase of the experiments. Animals in AF were cardioverted to SR for the EP study. Compared to baseline measurements, atrial MAPD90 was increased in all animals after either 7 or 21 days of burst pacing. However, the atrial MAPD90 increase was considerably longer at day 7 in G628S animals compared to controls (figure 2). The differences in right and left atrial MAP90 between G628S animals and controls were attenuated on day 21. The left atrial MAPD90 in the G628S animals was not significantly different than controls at the later time point.

Figure 2.

Change in MAPD90 at the termination study relative to the baseline study. a. The left panel shows changes in atrial MAPD90 for the indicated groups, and the right panel shows changes in ventricular MAPD90, measured from the basal left and right ventricles in close proximity to the atria. The bars represent the median change and the lines represent the corresponding inter-quartile range. For 1-week data: N=5 for both the controls and HERG-G628S groups. For the 3 week data: N=10 for the controls and N-7 for HERG-G628S groups, respectively. (* p ≤ 0.01, † p = 0.06, ‡ p =NS) b. Representative MAPD90 tracings from individual animals in the indicated groups for the indicated heart chamber. G is the KCNH2-G628S group, C is the control group,.

At the one week time point in the G628S animals, there appeared to be a more pronounced effect on the right compared to the left atria. This finding was not anticipated, so it was not part of our prospective analysis plans. Post-hoc analysis showed that this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.3 by Wilcoxon signed ranks test), although we cannot rule out the possibility that our study was underpowered to distinguish interatrial differences in therapeutic effect.

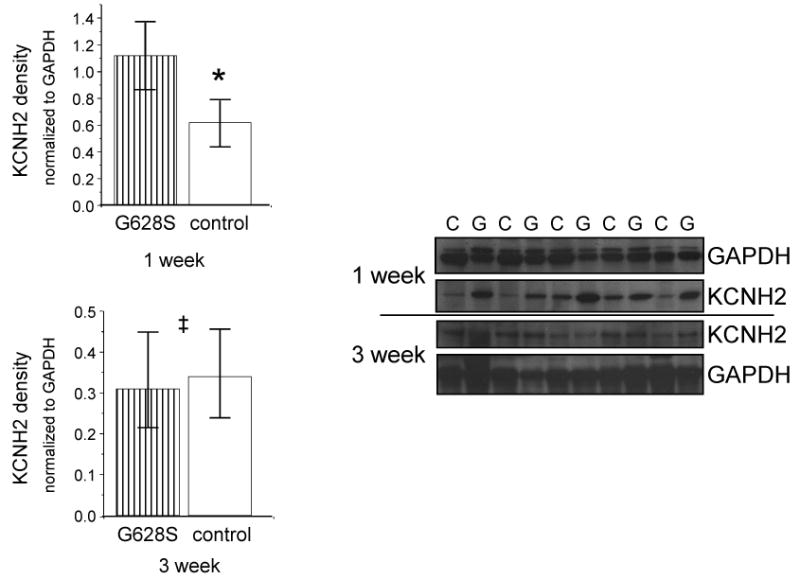

Protein expression

The observed physiological effects were compared to Western blot-determined KCNH2 expression levels. The median expression level of KCNH2 normalized to GAPDH was 1.12 (0.84, 1.37) among the G628 group compared to 0.62 (0.46, 0.72) among controls (p = 0.003), representing 79% higher KCNH2 levels in the G628S group at 1 week compared to control animals (figure 3). At 3 weeks, there were no statistically significant differences in KCNH2 expression between G628S animals and controls.

Figure 3.

KCNH2 protein expression measured with Western blot. The left panel shows the level of KCNH2 expression in the KCNH2-G628S group relative to the control group at the indicated time point. Individual bands were normalized to GAPDH prior to analysis. The right panel shows the actual western blot bands. (* p < 0.01, ‡ p =NS)

Effect on conduction time

Looking for alternative explanations for AF termination, we evaluated measures of atrial conduction while the animals were in SR during the invasive EP study. The P wave duration on surface ECG is a global assessment of the time required to activate the atria. The P wave duration increased in all burst-paced animals when compared to the pre-AF baseline, but there were no differences between G628S animals and controls at either 7- or 21-day time point. With the 7-day animals, we also assessed conduction times between the sinus node and the left and right atrial appendages. None of these measurements differed between groups (table).

TABLE.

| 7d control |

7d G628S |

21d control |

21d G628S |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 lead ECG | ||||

| P wave duration | 92 (86, 92) | 91 (71, 96) | 95 (85, 120) | 85 (75, 100) |

| PR interval | 120 (117, 124) | 119 (117, 121) | 120 (120, 130) | 130 (117, 138) |

| QRS interval | 70 (69, 78) | 66 (59, 78) | 75 (64, 80) | 70 (60, 70) |

| QTc | 392 (384, 402) | 395 (392, 401) | 411 (3668, 412) | 394 (375, 425) |

| heart rate | 106 (105, 114) | 105 (108, 129) | 100 (75, 130) | 93 (93, 115) |

| Intra-atrial conduction time (pacing 400 ms cycle length) | ||||

| SN → RAA | 54 (51, 55) | 43 (42, 47) | NP | NP |

| SN → LAA | 90 (69, 108) | 96 (86, 105) | NP | NP |

| RAA → LAA | 101 (92, 101) | 103 (89, 117) | NP | NP |

Abbreviations: 7d-7 day, 21d-21 day, QTc-QT interval corrected for heart rate using Bazett's formula, ms-millisecond, SN→RAA-pacing at sinus node and measurement of conduction time at right atrial appendage, SN→LAA-pacing at sinus node and measurement of conduction time at left atrial appendage, RAA→LAA-pacing at right atrial appendage and measurement of conduction time at left atrial appendage, NP-test not performed in that group; Data are reported as median (interquartile range). Time unit for all measures is milliseconds. p = NS for all between group comparisons.

Safety

Several measures of safety were evaluated. Atrial proarrhythmia was evaluated by looking for early afterdepolarizations (EADs) in the day 7 peak effect animals. There were no EADs at baseline heart rate. The heart rate in 2 animals was then slowed by localized cooling of the sinus node, and MAP90 recordings were repeated in left and right atrial areas away from the cooling site. Still, no EADs were observed. The ventricles were assessed for any electrophysiological changes. Comparing controls to G628S animals, no change was noted in QRS duration or QT interval on surface ECG, or in MAPD90 on MAP recordings (Figure 2, table). There were also no ventricular arrhythmias noted during the daily ECG recordings.

Discussion

Overall, we found that KCNH2-G628S gene transfer successfully prevented sustained AF, even with the very aggressive and persistent AF trigger of rapid burst pacing. The therapeutic effect correlated to APD prolongation. We saw no suggestion that alternative mechanisms of reentry disruption played a role; several measures of intra-atrial conduction were unchanged between groups. We also saw a direct correlation between therapeutic effect and the timing of transgene expression, starting shortly after gene transfer at a time that we and others have observed expression onset,14 and lapsing after a few weeks as adenovirus-mediated gene expression waned.16 We observed repeated termination of AF with daily electrocardiographic recordings, albeit over limited time periods each day. Within the constraints of that limit, we saw in the G628S animals reproducible onset of fibrillatory conduction with burst pacing and repeated termination of fibrillation a few beats after conclusion of the burst pacing episode. Our results are the first documentation of a molecular therapy to disrupt this pervasive and debilitating arrhythmia.

Mechanism of AF maintenance

Our data have implications for the continuing debate on the mechanism of AF. Our study was not equipped to answer the question of triggering mechanism, because we used an artificial trigger (the electronic pacemaker). Our data do provide insight into the mechanism of AF maintenance. Suggested mechanisms have included the possibilities that the triggering stimulus continues with the macroscopic appearance of AF coming from a breakdown in uniform conduction away from the trigger (so-called fibrillatory conduction) or that the trigger initiates persistent reentrant wavelets.9 In our model, the G628S animals continued to show evidence of fibrillatory conduction during the burst pacing episodes, with loss of organized atrial electrical activation and rapid, irregular activation of the atria, so our effective therapy affected neither trigger nor fibrillatory conduction. The disruption of AF in the G628S animals correlated with APD prolongation. If AF sustained by a triggered mechanism as some postulate, then APD prolongation should have worsened the situation by provoking more triggered activity. If reentry maintained AF as others have argued, then APD prolongation should have terminated the arrhythmia by causing the electrical activation wavefront to meet still-depolarized and therefore refractory cells. Since the episodes of AF reproducibly terminated in the G628S animals, our data support the hypothesis that AF sustains by a reentrant mechanism, at least in this model.

Translation of these findings to the prevention or treatment of AF

Our data suggest viability of KCNH2-G628S gene transfer for treatment of sustained AF. Current pharmaceutical options are limited by efficacy and safety concerns. Approximately half of patients started on an antiarrhythmic drug today will be back in AF within 1 year, and 10-30% will have therapy-limiting side effects.4, 5 In comparison to pharmacotherapy, gene therapy has the advantages of more robust ionic current block and of localized effect, allowing more aggressive action in the atria without danger of ventricular effects. Pharmacological block of an ion channel is controlled by drug biodistribution, affinity for the target channel and the need to bind the channel in a particular physiological state. Gene transfer with a dominant negative mutant circumvents these limitations by infiltrating and polluting individual channel function as channels are formed inside the cell.

The differences between drug and gene therapy become apparent when comparing our results to those of Blaauw et al., who investigated IKr blocking drugs in the goat burst-pacing AF model.17 At baseline, ibutilide and dofetilide increased atrial ERP approximately 20%. After 48 hours of burst pacing and AF, the ERP prolonging effects of the drugs were almost completely lost, and the drugs had no preventative effect against AF. Unfortunately, the QT-prolonging effect of the IKr blocking drugs was not lost, so drug dosing was limited by ventricular effects. In contrast, we saw that IKr disruption by gene therapy was durable through the time of gene expression, and there were no ventricular effects that would limit dose.

Broad translation to the treatment of AF will require a less invasive delivery method and stable long-term gene expression. Percutaneous access to the pericardial space has already been described for minimally invasive cardiac surgery and arrhythmia ablation.18, 19 Development of similar tool sets for gene painting should solve that problem. The 3 week limitation to gene expression in our study is a well reported characteristic of adenovirus vectors.16 This constraint would be unacceptable in patients who would need permanent therapy. Adeno-associated virus and lentivirus vectors have achieved long lasting, stable gene expression in other applications,20, 21 and they should work similarly for atrial gene painting. Of course, long term testing with an appropriate AF model and preferably continuous telemetry with a system that can reliably distinguish AF from burst pacing would be required to establish efficacy and stable expression prior to translation to the much more complex environment of permanent AF.

One potential concern is the utility of this approach in situations where atrial APD is already prolonged. Kirchoff et al. noted atrial APD prolongation and arrhythmia vulnerability in congenital long-QT syndrome patients with a variety of genotypes, and Johnson et al. found an association between early onset AF and KCNQ1 mutations in long-QT patients.22, 23 A dog model of ventricular tachypacing-induced heart failure found that atrial APD increased with occurrence of heart failure, and that increased atrial APD correlated with vulnerability for AF induction.24 Although a recent study showed that AF in human heart failure was actually associated with shortened atrial APD,25 the number of subjects in both studies is small raising the possibility that both mechanisms may be relevant to different situations. These findings raise the question of whether further APD prolongation might be helpful or harmful. For the most part, these are observational reports in very small numbers of patients, and clinical trials with pharmacological block of IKr has been associated with AF termination not AF induction.26 Of even further interest is a recent study of the KCNH2 polymorphism K897T. The common allele K897 is associated with average QT interval and an odds ratio of 1.25 for development of AF relative to the rare T897 allele that increases IKr and shortens ventricular repolarization times.27 Ultimately, more research is required to answer the question of possible interactions of atrial-specific G628S gene therapy in heart failure or other situations where atrial APD might be long at baseline.

Specific Application to Post-Operative AF

Application to the problem of post-cardiac surgery AF is a natural extension of our data. With the chest already opened for the surgical procedure, access to the cardiac atria for gene painting is straightforward. The timing of therapeutic effect in our experiments corresponds to the observed time of AF vulnerability after cardiac surgery, with peak AF risk 3 days after the surgical procedure, corresponding to the time of gene expression. For the most part, resolution of AF risk occurs 1-2 weeks post-op, which is shortly before loss of expression occurs with the adenovirus vector.28

Post-operative AF affects 30-50% of the several hundred thousand patients undergoing cardiac procedures each year, lengthening hospital and intensive care unit stay, and increasing risk for stroke, in-hospital and long-term mortality.29 The mechanism of post-operative AF remains controversial. Prior studies have implicated a variety of factors including pre-existing atrial fibrosis or expression levels of various ion channels, metabolic or oxidative stress on myocytes, alterations in connexin expression, adrenergic and/or purinergic and/or cholinergic stimulation.30-36 Our model would seem to be ideally suited for testing efficacy in the post-operative setting. Just like the human cardiac surgical situation, we open the chest, manipulate the heart, and see post-operative inflammation and adhesions (in all animals, including no-painting controls). In spite of this extensive manipulation, we see efficacy of G628S gene painting in the post-operative setting. These findings suggest that our intervention could have enormous impact on this pervasive problem.

Summary

Here we show that atrial gene painting with KCNH2-G628S lengthens atrial action potential duration and disrupts atrial fibrillation. The duration of these effects correlate to the time of gene expression, suggesting that longer lasting effects should be possible with expression vectors that allow long term, possibly permanent, gene expression. An important consistent finding with our method is the absence of ventricular effects from atrial painting. This localization of therapy distinguishes gene transfer approaches from conventional drug therapy. Not only does it increase the safety of the method, but it also potentially improves efficacy by allowing higher intensity atrial therapy without the limitation of concomitant ventricular adverse effects. Future studies could include investigation of long-term efficacy with a permanently expressing gene transfer vector, investigation of efficacy in other AF models (e.g. old age or pre-existing heart failure), and dissection of gene transfer effects on the target ion channel and other channels participating in the repolarization process. Taken together, our efficacy and safety data suggest that atrial gene painting with KCNH2-G628S could become an effective and safe therapy for the prevention or termination of atrial fibrillation.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources. This work was funded by grants from the NIH (HL93486, EB2846). Pacemaker equipment was donated by Medtronic, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN).

Footnotes

Disclosure. The authors declare no competing financial or conflicting interests.

References

- 1.Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Cha SS, Bailey KR, Abhayaratna WP, Seward JB, Tsang TS. Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence. Circulation. 2006;114:119–25. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, Singer DE. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285:2370–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, Leip EP, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Murabito JM, Kannel WB, Benjamin EJ. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2003;107:2920–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072767.89944.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jais P, Cauchemez B, Macle L, Daoud E, Khairy P, Subbiah R, Hocini M, Extramiana F, Sacher F, Bordachar P, Klein G, Weerasooriya R, Clementy J, Haissaguerre M. Catheter ablation versus antiarrhythmic drugs for atrial fibrillation: the A4 study. Circulation. 2008;118:2498–505. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.772582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camm AJ. Safety considerations in the pharmacological management of atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2008;127:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cappato R, Calkins H, Chen SA, Davies W, Iesaka Y, Kalman J, Kim YH, Klein G, Natale A, Packer D, Skanes A, Ambrogi F, Biganzoli E. Updated Worldwide Survey on the Methods, Efficacy, and Safety of Catheter Ablation for Human Atrial Fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:32–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.859116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox JL, Schuessler RB, Lappas DG, Boineau JP. An 8 1/2-year clinical experience with surgery for atrial fibrillation. Ann Surg. 1996;224:267–73. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199609000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edgerton JR, McClelland JH, Duke D, Gerdisch MW, Steinberg BM, Bronleewe SH, Prince SL, Herbert MA, Hoffman S, Mack MJ. Minimally invasive surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: six-month results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:109–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.09.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nattel S. Therapeutic implications of atrial fibrillation mechanisms: can mechanistic insights be used to improve AF management? Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54:347–60. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00562-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer A, McDonald A, Donahue JK. Pathophysiological findings in a model of atrial fibrillation and severe congestive heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:764–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kikuchi K, McDonald AD, Sasano T, Donahue JK. Targeted Modification of Atrial Electrophysiology by Homogeneous Transmural Atrial Gene Transfer. Circulation. 2005;111:264–70. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153338.47507.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Z, Gong Q, Ye B, Fan Z, Makiekski J, Rovertson G, January C. Properties of HERG channels stably expressed in HEK293 cells studied at physiological temperature. Biophys J. 1998;74:230–41. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77782-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donahue JK, Heldman A, Fraser H, McDonald A, Miller J, Rade J, Eschenhagen T, Marban E. Focal modification of electrical conduction in the heart by viral gene transfer. Nat Med. 2000;6:1395–8. doi: 10.1038/82214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauer A, McDonald AD, Nasir K, Peller L, Rade JJ, Miller JM, Heldman AW, Donahue JK. Inhibitory G Protein Overexpression Provides Physiologically Relevant Heart Rate Control in Persistent Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation. 2004;110:3115–20. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147185.31974.BE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasano T, McDonald A, Kikuchi K, Donahue JK. Molecular ablation of ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction. Nat Med. 2006;12:1256–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quinones M, Leor J, Kloner R, Ito M, Patterson M, Witke W, Kedes L. Avoidance of immune response prolongs expression of genes delivered to the adult rat myocardium by replication defective adenovirus. Circulation. 1996;94:1394–401. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.6.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blaauw Y, Schotten U, van Hunnik A, Neuberger H, Allessie M. Cardioversion of persistent atrial fibrillation by a combination of atrial specific and non-specific class III drugs in the goat. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stevens JH, Burdon TA, Peters WS, Siegel LC, Pompili MF, Vierra MA, St Goar FG, Ribakove GH, Mitchell RS, Reitz BA. Port-access coronary artery bypass grafting: a proposed surgical method. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;111:567–73. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(96)70308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sosa E, Scanavacca M, D'Avila A, Pilleggi F. A new technique to perform epicardial mapping in the electrophysiology laboratory. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1996;7:531–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1996.tb00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snyder R, Miao C, Patijn G, Spratt S, Danos O, Nagy D, Gown A, Winther B, Meuse L, Cohen L, Thompson A, Kay M. Persistent and therapeutic concentrations of human factor IX in mice after hepatic gene transfer of recombinant AAV vectors. Nat Genet. 1997;16:270–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naldini L, Blomer U, Gage FH, Trono D, Verma IM. Efficient transfer, integration, and sustained long-term expression of the transgene in adult rat brains injected with a lentiviral vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11382–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirchhof P, Eckardt L, Franz MR, Monnig G, Loh P, Wedekind H, Schulze-Bahr E, Breithardt G, Haverkamp W. Prolonged atrial action potential durations and polymorphic atrial tachyarrhythmias in patients with long QT syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:1027–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.03165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson JN, Tester DJ, Perry J, Salisbury BA, Reed CR, Ackerman MJ. Prevalence of early-onset atrial fibrillation in congenital long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:704–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li D, Fareh S, Leung T, Nattel S. Promotion of atrial fibrillation by heart failure in dogs: atrial remodeling of a different sort. Circulation. 1999;100:87–95. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Workman AJ, Pau D, Redpath CJ, Marshall GE, Russell JA, Norrie J, Kane KA, Rankin AC. Atrial cellular electrophysiological changes in patients with ventricular dysfunction may predispose to AF. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:445–51. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pederson O, Bagger H, Keller N, Marchant B, Kober L, Torp-Peterson C. Efficacy of dofetilide in the treatment of atrial fibrillation-flutter in patients with reduced left ventricular function: a Danish investigations of arrhythmia and mortality on dofetilide (diamond) substudy. Circulation. 2001;104:292–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinner MF, Pfeufer A, Akyol M, Beckmann BM, Hinterseer M, Wacker A, Perz S, Sauter W, Illig T, Nabauer M, Schmitt C, Wichmann HE, Schomig A, Steinbeck G, Meitinger T, Kaab S. The non-synonymous coding IKr-channel variant KCNH2-K897T is associated with atrial fibrillation: results from a systematic candidate gene-based analysis of KCNH2 (HERG) Eur Heart J. 2008;29:907–14. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathew JP, Fontes ML, Tudor IC, Ramsay J, Duke P, Mazer CD, Barash PG, Hsu PH, Mangano DT. A multicenter risk index for atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery. JAMA. 2004;291:1720–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mariscalco G, Klersy C, Zanobini M, Banach M, Ferrarese S, Borsani P, Cantore C, Biglioli P, Sala A. Atrial fibrillation after isolated coronary surgery affects late survival. Circulation. 2008;118:1612–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.777789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goette A, Juenemann G, Peters B, Klein H, Roessner A, Huth C, Rocken C. Determinants and consequences of atrial fibrosis in patients undergoing open heart surgery. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54:390–6. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00251-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plante I, Fournier D, Mathieu P, Daleau P. A pilot study to estimate the feasibility of assessing the relationships between polymorphisms in hKv1.5 and atrial fibrillation in patients following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24:41–4. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(08)70546-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korantzopoulos P, Kolettis T, Siogas K, Goudevenos J. Atrial fibrillation and electrical remodeling: the potential role of inflammation and oxidative stress. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9:RA225–RA229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korantzopoulos P, Kolettis TM, Siogas K, Goudevenos JA. The emerging role of inflammation in atrial fibrillation and the potential of anti-inflammatory interventions. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2207–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryu K, Li L, Khrestian CM, Matsumoto N, Sahadevan J, Ruehr ML, Van Wagoner DR, Efimov IR, Waldo AL. Effects of sterile pericarditis on connexins 40 and 43 in the atria: correlation with abnormal conduction and atrial arrhythmias. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1231–H1241. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00607.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Workman AJ, Pau D, Redpath CJ, Marshall GE, Russell JA, Kane KA, Norrie J, Rankin AC. Post-operative atrial fibrillation is influenced by beta-blocker therapy but not by pre-operative atrial cellular electrophysiology. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:1230–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amar D, Zhang H, Miodownik S, Kadish AH. Competing autonomic mechanisms precede the onset of postoperative atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1262–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00955-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]