Summary

Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), which are coupled to second messenger pathways via G proteins, modulate glutamatergic and GABAergic neurotransmission. Because of their role in modulating neurotransmission, mGluRs are attractive therapeutic targets for anxiety disorders. Previously we showed that mGluR8−/− male mice showed higher measures of anxiety in the open field and elevated plus maze than age-matched wild-type mice. In this study, we assessed the potential effects of acute pharmacological modulation of mGluR8 on measures of avoidable and unavoidable anxiety. In addition to wild-type mice, we also tested apolipoprotein E-deficient (Apoe−/−) mice, as these mice show increased levels of anxiety-like behaviors and therefore might show an altered sensitivity to mGluR8 stimulation. mGluR8 stimulation with the specific agonist DCPG, or modulation with AZ12216052, a new, positive allosteric modulator of mGluR8 reduced measures of anxiety in both wild-type mice. The effects of mGluR8 positive allosteric modulators, which only affect neurotransmission in the presence of extracellular glutamate, seem particularly promising for patients with anxiety disorders showing benzodiazepine insensitivity.

Keywords: metabotropic, group-III mGluR, allosteric modulator, behavior

INTRODUCTION

G protein-coupled metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) modulate excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission (Pin & Duvoisin, 1995; Conn & Pin, 1997). Eight different mGluR receptors (mGluR1-mGluR8) have been identified and classified into 3 groups according to their sequence identity, pharmacological profile and signal transduction mechanisms. Group-III receptors are generally located presynaptically, where they regulate neurotransmitter release (Cartmell & Schoepp, 2000). In transfected cells, mGluR8, a member of group-III receptors that also comprises mGluR4, mGluR6, and mGluR7, is coupled to the inhibition of adenylyl cyclase (Duvoisin et al., 1995; Saugstad et al., 1997).

Because of their role in modulating neurotransmission, mGluRs are attractive targets for therapies aimed at treating anxiety disorders (reviewed in Swanson et al., 2005). Consistent with a role for mGluR8 in the regulation of anxiety, increased measures of anxiety in the open field and the elevated plus maze were seen in mGluR8−/− mice (Linden et al., 2002; Duvoisin et al., 2005; although see Fendt et al., 2009). The increased measures of anxiety are not limited to anxiety tests involving avoidable anxiety-provoking stimuli. The acoustic startle response was also higher in mGluR8−/− than wild-type (Wt) male mice (Duvoisin et al., 2010). The acoustic startle reflex is a skeletal muscle response following a sudden auditory stimulus. This reflex is increased by unconditioned acoustic stimuli and modulated by anxiogenenic and anxiolytic compounds (Swerdlow et al., 1986, 1989; Liang et al., 1992; Morgan et al., 1993). To compare measures of anxiety involving avoidable anxiety-provoking stimuli such as those assessed in the elevated zero maze and unavoidable anxiety provoking stimuli the acoustic startle response is preferred over fear-potentiated startle, which is used to assess expression of fear as a learned reaction to stimuli that predict danger (conditioned fear).

While much can be learned regarding the role of mGluR8 in measures of anxiety using constitutively mutant mice, potential effects of mGluR8 deficiency in utero, during postnatal development, or during early adulthood might have contributed to the observed behavioral phenotype. In the current study, the effects of acute pharmacological modulation of mGluR8 on measures of anxiety were assessed in wild-type male mice, as well as in apolipoprotein E-deficient (Apoe−/−) mice. Apoe−/− mice show increased levels of anxiety-like behaviors and therefore might show an increased sensitivity to mGluR8 stimulation. We used the orthosteric agonist (S)-3,4-dicarboxyphenylglycine (DCPG), which in transfected cells is specific for mGluR8 (Thomas et al., 2001); and we identified and tested a novel positive allosteric modulator of mGluR8, AZ12216052.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

C57BL/6J wild-type male mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Apoe−/− mice were generated by N. Maeda (UNC, NC) and obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were kept on 12:12 hr light-dark schedule (lights on at 6 AM) with chow (PicoLab Rodent Diet 20, #5053; PMI Nutrition International, St. Louis, MO) and water given ad libitum. All the experiments reported here were conducted in accordance with NIH guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at OHSU.

Drugs

The native human mGluR8b receptor was stably expressed in Human Embryonic Kidney (HEK) 293 cells that co-expressed the Glutamate/Aspartate transporter (GLAST; clone#32, GHEK32). This double stable cell line was maintained in DMEM (Gibco), 10% dialyzed FCS, 5 µg/ml Blasticidin, 200 µg/ml Zeocin and 2 mM L-glutamine. Compounds were tested using a [35S]GTPγS binding assay. Membranes were prepared by harvesting cells in PBS, containing 1 mM EDTA, and spinning at 2500 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. The pellets were resuspended in 20 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4, 10 mM EDTA, homogenized, and centrifuged at 25,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. The pellet was re-homogenized in 20 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4, 0.1 mM EDTA, and re-centrifuged at 25,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in the same buffer and homogenized briefly. Protein concentration was determined using the BCA Protein Assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Membranes (50 µg protein) were incubated in 500 µl assay buffer (20 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2), containing 3 µM GDP and 0.1 nM [35S]GTPγS (1250 Ci/mmol), with the positive allosteric modulator compound for 15 min, then 300 nM glutamate (EC10) was added for 30 min at 30°C. Reactions were carried out in duplicate 2 ml polypropylene 96 well plates, and terminated by vacuum filtration through GF/B microfilters; plates were washed with 4 × 1.5 ml ice-cold water, dried, and 35 µl Microscint 20 (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) was added to each well. Bound radioactivity was quantified using a Packard TopCount liquid scintillation counter.

DCPG (Tocris) and AZ12216052 (Astra-Zeneca) were dissolved in DMSO and administered i.p. 2 hours prior to testing at the concentrations indicated in the text. The volume of DMSO injected per mouse was 100 µl, independent of the drug dose or drug used. This amount of DMSO, which is necessary for AZ12216052 solubility, did not cause any detectable sickness in the mice or effect on activity in the home cage, but it did heighten basal anxiety-like measures. The same mice were tested in the elevated zero maze on day 1 and for the acoustic startle response on day 2.

Behavioral Analysis

Elevated Zero Maze

The custom built elevated zero maze consisted of two enclosed areas and two open areas, identical in length to the open and closed arms in the elevated plus maze (35.5 cm; Kinder Scientific, Poway, CA). Mice were placed in the closed part of the maze and allowed free access for 10 min, as described (Benice et al., 2006). They could spend their time either in a closed safe area or in a more anxiety-provoking open area. The luminescence was 500 lux. White noise generators were used to generate a background noise level of 80 db. A video tracking system (Noldus Information Technology, Sterling, VA) set at 6 samples/second was used to calculate the distance moved, velocity defined as total distance (cm)/total time (s), and percent time spent in the open areas of the maze. The elevated zero maze was cleaned with 5% acetic acid between animals.

Acoustic Startle

Acoustic startle was tested in Hamilton-Kinder (Poway, CA) startle chambers as described (Robertson et al., 2005). The mice are placed in adjustable acrylic holders within the startle chambers and have no room to move. After a 5-min acclimation, the baseline response was measured. The baseline was defined as the amplitude measure in the absence of any acoustic stimulus. Acoustic pulses were given, increasing from 80 dB to120 dB, using increments of 2 dB within a 500 msec window and the startle amplitude, the maximum force in newtons (N) or the peak voltage that occurred, was used as outcome measure. Each acoustic stimulus intensity was given once. Analyzing the peak startle amplitude rather than the mean startle response assured measurement of the acoustic startle response and excluded potential movement artifact during the recording window. White noise was used for the acoustic stimuli. Wideback background noise (72 dB) was used during testing. The acoustic startle response, defined as the average startle amplitude in responses to different tone intensities from 80 dB to 120 dB, was determined.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Differences among means were evaluated by ANOVA, followed by Student’s t-test or Tukey-Kramer posthoc tests, as indicated, using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA). For the acoustic startle response, startle intensity was used as factor in the analysis. For all analyses, the null hypothesis was rejected at the 0.05 level.

RESULTS

Identification of a novel positive allosteric modulator of mGluR8

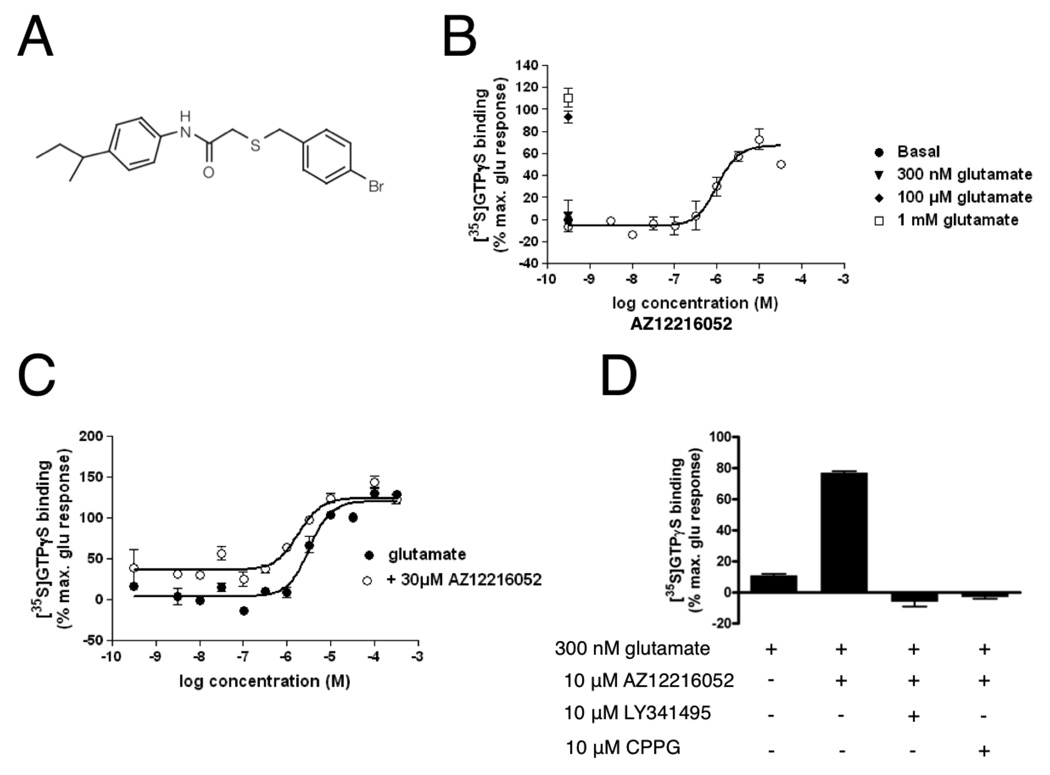

The compound, AZ12216052 (Fig. 1A), was found to potentiate the activity of glutamate at the human mGluR8b receptor expressed in GHEK cells. Using a [35S]GTPγS binding assay, AZ12216052 potentiated the effect of 300 nM glutamate, with an EC50 of 1.0 µM, and a maximum efficiency (Emax) of 71% compared to a saturating 1 mM glutamate stimulation (Fig. 1B). Up to 30 µM AZ12216052 had no effect in GTPγS binding assays using membranes prepared from mGluR4-expressing GHEK cells. As shown in Fig. 1C, the concentration-response of glutamate in the presence of 30 µM AZ12216052 was shifted 1.8 fold to the left compared to glutamate alone. It should also be noted that AZ12216052 (30 µM) elevated GTPγS binding even in the presence of low concentrations of added glutamate. This is most likely due to the presence of endogenous glutamate in the membrane preparations since the activity can be reduced by excessive washing of the membranes or by preincubation of the membranes with GPT (glutamate pyruvate transaminase, a glutamate degrading enzyme; data not shown). The positive allosteric modulator effects of AZ12216052 were inhibited by the group-II/III antagonists LY341495 and CPPG (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. Identification of AZ12216052, a novel positive allosteric modulator of mGluR8.

A. Structure of AZ12216052. B. GTPγS binding assay in the presence of 300 nM glutamate relative to GTPγS binding in 1 mM glutamate alone. C. 30 µM AZ12216052 shifts the glutamate concentration-response curve to the left. D. The potentiator effect of AZ12216052 on mGluR8 is inhibited by group-II/III antagonists LY341495 and CPPG. In panels B–D,100% is the maximal GTPγS binding in the presence of 1 mM glutamate.

DCPG reduces measures of anxiety in the elevated zero maze

To determine if acute stimulation of mGluR8 reduces measures of anxiety, the mGluR8 agonist DCPG was used. In addition to Wt mice, mice deficient in apolipoprotein E (Apoe−/−) were included, as they show an increase in measures of anxiety (Raber et al., 2000) and might be less sensitive to the effects of DCPG, as was found for histamine H3 receptor antagonists (Bongers et al., 2004). When dissolved in saline, DCPG at 25 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg did not affect measures of anxiety (Table 1). However, when dissolved in DMSO, DCPG at 150 mg/kg reduced measures of anxiety in the elevated zero maze (*p < 0.05 versus vehicle-treated control). However, at that dose DCPG also reduced the velocity of the mice (vehicle: 2.9 ± 0.6 cm/sec; DCPG: 1.2 ± 0.3 cm/sec, p < 0.05; n = 8–9 mice/treatment). It should be noted that the background anxiety-like behavior was elevated upon DMSO vehicle, compared to saline (time in open areas; saline: 169 ± 24 s; DMSO: 71 ± 23 s; t = 3.051, p = 0.01; n = 7 mice/treatment). At 150 mg/kg, DCPG did not affect the acoustic startle response of Wt or Apoe−/− mice (F = 0.018, p = 0.865).

Table 1.

Effects of DCPG dissolved in saline on measures of anxiety in the elevated zero maze.

| Wt | Apoe−/− | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline (n = 7) | DCPG (25 mg/kg) (n = 8) |

Saline (n = 5) | DCPG (25 mg/kg) (n = 7) |

|

| Time in Open Areas (s) |

169 ± 23 | 153 ± 23 | 169 ± 21 | 143 ± 12 |

| Velocity (cm/s) | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.2 |

| Saline (n = 8) | DCPG (100 mg/kg) (n = 8) |

|||

| Time in Open Areas (s) |

203 ± 25 | 166 ± 21 | ||

| Velocity (cm/s) | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.3 |

In subsequent experiments DCPG was dissolved in DMSO and used at 3, 10, or 30 mg/kg. In 2-month-old Wt mice, DCPG reduced measures of anxiety at 3, but not at 10 or 30, mg/kg in the elevated zero maze (Fig. 2A). Importantly, DCPG did not affect velocity in the mice (vehicle: 3.0 ± 0.6 cm/sec; DCPG 3: 4.3 ± 0.3; DCPG 10: 4.1 ± 0.5; DCPG 30: 3.4 ± 0.2 cm/sec). Thus, potential effects of DCPG on activity did not contribute to the effects of DCPG on measures of anxiety. In contrast, in Apoe−/− mice, DCPG at 10 or 30, but not at 3, mg/kg reduced measures of anxiety in the elevated zero maze (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Effects of DCPG on anxiety-like behaviors.

A. Effects of DCPG (3, 10, or 30 mg/kg) on measures of anxiety of 2-month-old Wt and Apoe−/− male mice in the elevated zero maze. *p < 0.05 versus genotype-matched vehicle-treated control. There was an overall effect of genotype on time spent in the open areas (F = 58.3, p < 0.0001). DCPG did not affect velocity in Wt (vehicle: 3.0 ± 0.6 cm/sec; DCPG 3: 4.3 ± 0.3; DCPG 10: 4.1 ± 0.5; DCPG 30: 3.4 ± 0.2 cm/sec) or Apoe−/− mice (vehicle: 2.2 ± 0.6 cm/sec; DCPG 3: 2.7 ± 0.6; DCPG 10: 2.0 ± 0.6; DCPG 30: 1.4 ± 0.4 cm/sec). There was no effect of genotype on velocity. n = 8 mice/genotype/dose. B. Effects of DCPG (3, 10, or 30 mg/kg) on baseline startle response in 3-month-old Wt and Apoe−/− mice. DCPG increased the baseline startle response (F = 25.92, p = 0.0004). n = 8 mice/genotype/dose.

DCPG did not affect the acoustic startle response (Table 2), but did increase the baseline response with Wt and Apoe−/− mice similarly affected (p = 0.0004, n = 8 mice/dose, Fig. 2B). There was a treatment effect (F = 6.997, p = 0.0004) and the baseline startle response was lower in vehicle-treated mice than mice treated with DCPG at 3 mg/kg (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Effects of DCPG dissolved in DMSO on the acoustic startle response1.

| DMSO vehicle (n = 8) |

DCPG (3 mg/kg) (n = 8) |

DCPG (10 mg/kg) (n = 8) |

DCPG (30 mg/kg) (n = 7) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Acoustic Startle Response Wt mice1 |

0.65 ± 0.04 | 0.88 ± 0.06 | 0.81 ± 0.05 | 0.99 ± 0.06 |

| Mean Acoustic Startle Response Apoe−/− mice1 |

0.47 ± 0.05 | 0.58 ± 0.06 | 0.51 ± 0.06 | 0.28 ± 0.01 |

DCPG did not reduce the acoustic startle response the acoustic startle response in Wt (F = 2.806, p = 0.0579) or Apoe−/− mice (F = 1.785, p = 0.1729).

Effects of mGluR8 positive allosteric modulator on measures of anxiety

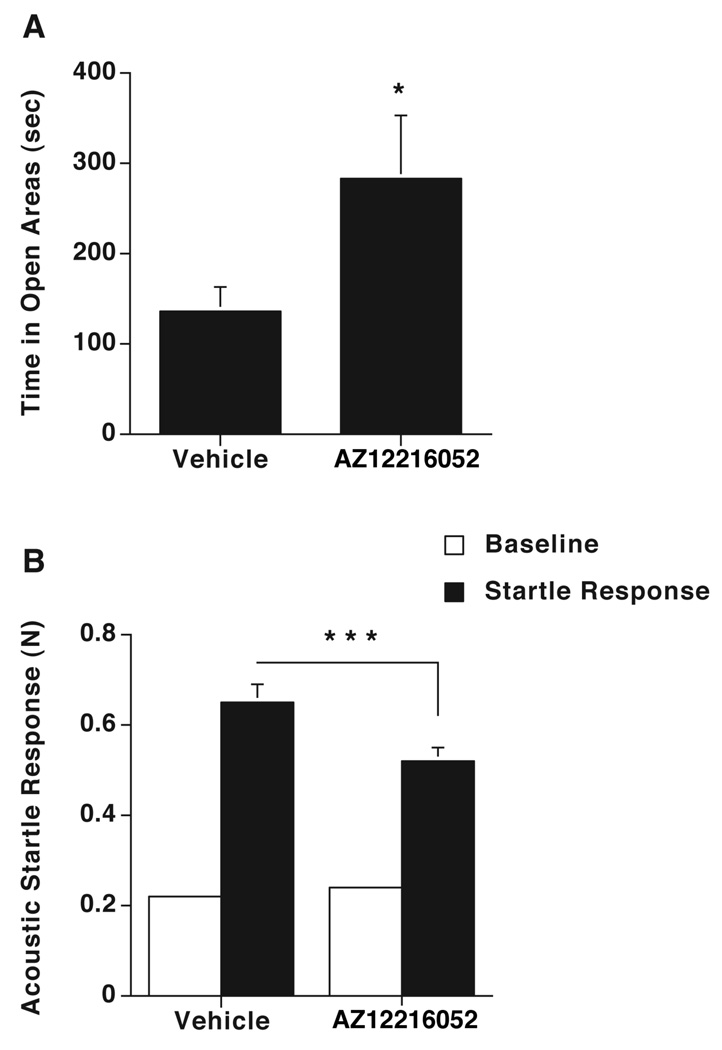

Next, we tested whether the mGluR8 positive allosteric modulator AZ12216052 affects measures of anxiety. In 2-month-old Wt mice, AZ12216052 (10 mg/kg) reduced measures of anxiety in the elevated zero maze (Fig. 3A). AZ12216052 did not affect the velocity of the mice (vehicle: 3.0 ± 0.6; AZ12216052: 3.2 ± 0.8 cm/sec), thus its effects on measures of anxiety are not due to changes in activity levels. In addition, AZ12216052 reduced the acoustic startle response (Fig. 3B) without having effects on the baseline response (vehicle: 0.22 ± 0.01; AZ12216052: 0.24 ± 0.01 N).

Figure 3. Effects of AZ12216052 on anxiety-like behaviors.

A. Effects of AZ12216052 (10 mg/kg) on measures of anxiety of 2-month-old Wt mice. AZ12216052 increased the time spent in the anxiety-provoking open areas of the elevated zero maze (p = 0.03, n = 8 mice/treatment). B. Effects of AZ12216052 on acoustic startle response of 2-month-old mice (vehicle: 0.65 ± 0.04; AZ12216052: 0.52 ± 0.03 N; F = 15.32, p < 0.0001, n = 8 mice/treatment). AZ12216052 had no effects on the baseline response (vehicle: 0.22 ± 0.01; AZ12216052: 0.24 ± 0.01 N). *p < 0.05 versus vehicle. n = 8 mice/treatment. The thresholds for the acoustic startle response were for vehicle 100 dB and for AZ12216052 104 dB.

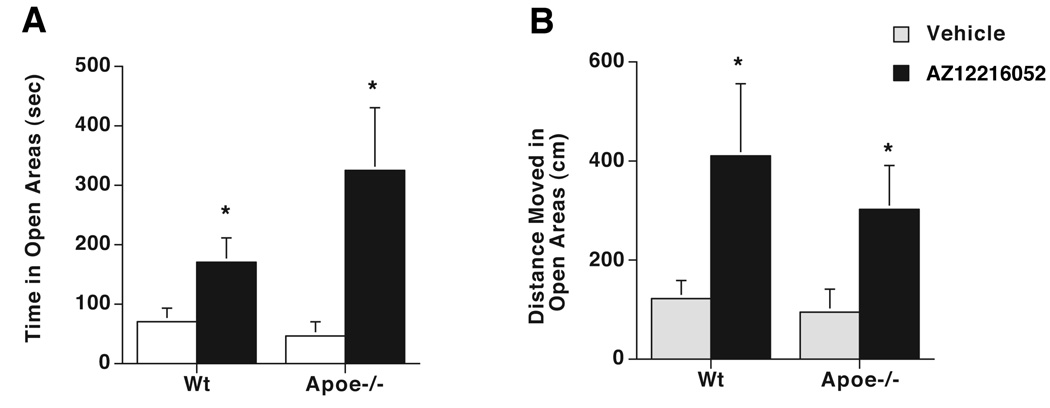

To determine whether the effects of AZ12216052 on measures of anxiety are age-dependent and more pronounced in Apoe−/− mice, 5-month-old mice were treated with AZ12216052. AZ12216052 similarly reduced measures of anxiety in Apoe−/− and Wt mice (Fig. 4). AZ12216052 did not affect velocity (vehicle: 1.8 ± 0.3 cm/sec; AZ12216052: 2.1 ± 0.4 cm/sec) in the mice, excluding that potential effects of AZ12216052 on activity levels contributed to the effects of AZ12216052 on measures of anxiety. However, in contrast to the effects of AZ12216052 on the acoustic startle response at 2 months of age, AZ12216052 did not affect the acoustic startle response in 5-month-old Apoe−/− or Wt mice (data not shown).

Figure 4. Effects of AZ12216052 (10 mg/kg) on measures of anxiety in 5-month-old Wt and Apoe−/− mice.

(A) Time spent in the open areas of the maze. (B) Distance moved in the open areas of the maze. *p < 0.05 versus vehicle-treated genotype-matched control. AZ12216052 did not affect velocity in wild-type (vehicle: 1.8 ± 0.3 cm/sec; AZ12216052: 2.1 ± 0.4 cm/sec) or Apoe−/− (vehicle: 1.9 ± 0.4 cm/sec; AZ12216052: 1.4 ± 0.4 cm/sec) male mice. n = 7–8 wild-type mice; n = 5–6 Apoe−/− mice.

DISCUSSION

Metabotropic glutamate receptors have been shown throughout the brain to be important regulators of neurotransmission. The data of the current study show that acute modulation of mGluR8 reduces behavioral measures of anxiety. These data are consistent with other behavioral studies in rodents (Helton et al., 1998; Klodzinska et al., 2002; Linden et al., 2002; Tizzano et al., 2002; Linden et al., 2003a; Linden et al., 2003b; Duvoisin et al., 2005), supporting group-III mGluRs as therapeutic targets to treat anxiety disorders. LY354740, a group II mGluR agonist with some activity on mGluR8, was also reported to have anxiolytic properties in humans and rats (Monn et al., 1997; Grillon et al., 2003).

We show here that pharmacological modulation of mGluR8 has anxiolytic properties when given systemically in mouse models of anxiety. In contrast to our data, no anxiolytic effects were observed in the conflict drinking Vogel test following central administration in the basolateral amygdala or CA1 region of the hippocampus in rats (Stachowicz et al., 2005). Although these data might suggest that brain regions other than the basolateral amygdala and CA1 region of the hippocampus are important for the effects of DCPG on measures of anxiety, we cannot exclude that differences in vehicle, test of anxiety used, and species tested contributed to these divergent findings. Interestingly, acquisition and expression of conditioning fear was inhibited in rats following injection of DCPG in the lateral amygdala (Schmid and Fendt, 2006). Future studies are warranted to assess potential effects of DCPG on measures of anxiety and conditioned fear in mice following site-specific injections.

Interestingly, the anxiolytic activity of DCPG was only observed upon the elevated anxiety-like behavior caused by the DMSO vehicle. This suggests that mGluR8 modulation might be effective at reducing heightened anxiety levels without much effect on baseline anxiety responses. This interpretation is consistent with the recent work of Palazzo et al. (2008), who find that DCPG had no effect on anxiety-like behaviors in normal rats, but had anxiolytic effects in the arthritic pain state. DMSO is often used to assess anti-nociceptive and anxiolytic effects of test compounds (Kathuria et al. 2002) and administered i.p. did not effect the antitumor agent paclitaxel-evoked paw withdrawal (Rahn et al., 2008) or paw withdrawal latency to a thermal stimulus (Malan et al., 2001, Ibrahim et al., 2004) and DMSO administered into the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray did not affect nociception (Fossum et al., 2008). However, as topical application of DMSO (100%) induced hyperpathic sensitization to a supra-threshold heating stimulus (50 0C/7 s) in rats (Bastos et al., 2010), we cannot completely exclude potential nociceptive effects of DMSO under our testing conditions. Nevertheless, these data support the selective stimulation of mGluR8 to treat conditions of heightened anxiety levels while not affecting normal anxiety levels.

We report for the first time the actions of the novel mGluR8 compound AZ12216052 on mouse behavior. This compound is likely a positive allosteric modulator of mGluR8, even though we did observe a small basal activity in GTPγS binding experiments. This activity could be caused by an intrinsic agonist activity of the compound in GTPγS assays, but is more likely due to low levels of endogenous glutamate in the cell culture medium. The specificity of AZ12216052 remains undefined. It was not effective on mGluR4 in GTPγS binding assays, and initial screening with all other mGluRs was also negative. Site-directed mutagenesis studies have generally shown that allosteric modulators bind to mGluRs within the transmembrane domain. Because this domain is not well conserved between different receptors, it is thought that allosteric modulators will have higher selectivity. Further studies will be needed to determine the specificity of AZ12216052.

However, while DCPG and AZ12216052 both reduced measures of anxiety in tests involving avoidable anxiety-provoking stimuli, they had differential effects on measures of anxiety in tests involving unavoidable anxiety-provoking stimuli. In 2-month-old mice, DCPG increased the baseline response while AZ12216052 reduced the acoustic startle response without affecting the baseline response. The ability of AZ12216052 to reduce the acoustic startle response was dependent on the age of the mice as it was seen in 2- but not 5-month-old mice. Since AZ12216052 is a pharmacological modulator and is effective when local glutamatergic neurotransmission is elevated, these data suggest that mGluR8 receptor activation could be higher in 2-month-old than in 5-month-old mice.

Within the amygdala, the basolateral nucleus plays an important role in modulating measures of anxiety in tests involving avoidable anxiety-provoking stimuli like the elevated plus maze and elevated zero maze, while the central nucleus plays an important role in modulating measures of anxiety in tests involving unavoidable anxiety-provoking stimuli like the acoustic startle response (Killcross et al., 1997). Thus, the differential effects of AZ12216052 on measures of anxiety and the acoustic startle response seen in 5-, but not 2-, month-old mice also suggests that there might be age-related difference in mGluR8 activation in the basolateral versus central nucleus of the amygdala.

Apoe−/− mice were less sensitive than Wt mice to the anxiety-reducing effects of DCPG in the elevated zero maze. At 3 mg/kg, DCPG reduced measures of anxiety in Wt mice in the elevated zero maze, while higher doses were required to see anxiety-reducing effects of DCPG in Apoe−/− mice. These data are consistent with the reduced sensitivity of Apoe−/− mice to the anxiety-reducing effects of H3 receptor antagonists on measures of anxiety in the elevated plus maze (Bongers et al., 2004). These data also support the reported interaction between histamine and glutamatergic neurotransmission (Haas, 1984; Bekkers, 1993; Vorobjev et al., 1993; Brown et al., 1995; Brown & Reymann, 1996; Payne & Neumann, 1997; Brown et al., 2001) and suggest that the dosing of mGluR8 agonists required to reduce measures of anxiety might need to be adjusted based on the histaminergic function. The histaminiergic function might also contribute to the inverted U-shape response with regard to anxiolytic effects of DCPG seen in the elevated zero maze in Wt, but not in Apoe−/− mice. In contrast to the elevated zero maze, no differential genotype-dependent effects of DCPG on the baseline startle response were observed. This suggests that a distinct brain circuitry might be involved in the effects seen in anxiety tests involving avoidable and unavoidable anxiety-provoking stimuli. Within the amygdala, the basolateral nucleus plays an important role in modulating measures of anxiety in tests involving avoidable anxiety-provoking stimuli like the elevated plus maze and elevated zero maze, while the central nucleus plays an important role in modulating measures of anxiety in tests involving unavoidable anxiety-provoking stimuli like the acoustic startle response (Killcross et al., 1997).

Positive allosteric modulation of mGluR8 shows great promise as pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders. First, positive allosteric modulators are only effective in the presence of an orthosteric ligand, allowing for finer tuning of physiological responses than the ON/OFF effects of agonists and antagonists. Second, they can possess greater selectivity among homologous receptor families than compounds that bind to orthosteric sites, which are usually highly conserved among receptor families. Third, especially for the significant portion of patients with anxiety disorders showing benzodiazepine insensitivity, a mGluR8-selective compound seems particularly promising as it would provide a novel therapeutic target (Schlegel et al., 1994; Kaschka et al., 1995; Roy-Byrne et al., 1996; Sundstrom et al., 1997).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Jessica Siegel for help with the behavioral testing, Heather Gosnell and Danny Winder for discussions and advice in writing the manuscript. This work was supported by NIMH R01 MH77647.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Bastos LC, Tonussi CR. PGE2-induced lasting nociception to heat: Evidence for a selective involvement of A-delta fibres in the hyperpathic component of hyperalgesia. Eur J Pain. 2010;14:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers Enhancement by histamine of NMDA-mediated synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Science. 1993;261:104–106. doi: 10.1126/science.8391168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benice T, Rizk A, Pfankuch T, Kohama S, Raber J. Sex-differences in age-related cognitive decline in C57BL/6J mice associated with increased brain microtubule-associated protein 2 and synaptophysin immunoreactivity. Neuroscience. 2006;137:413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongers G, Leurs R, Robertson J, Raber J. Role of H3 receptor-mediated signaling in anxiety and cognition in wild-type and Apoe−/− mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:441–449. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, Fedorov N, Haas HL, Reymann KG. Histaminergic modulatio of synaptic plasticity in area CA1 of rat hippocampal slices. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:181–190. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00138-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, Reymann KG. Histamine H3 receptor-mediated depression of synaptic transmission in the dentate gyrus of the rat in vitro. J Physiol Lond. 1996;496:175–184. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Stevens DR, Haas HL. The physiology of brain histamine. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;63:637–672. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartmell J, Schoepp DD. Regulation of neurotransmitter release by metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurochem. 2000;75:889–907. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn PJ, Pin JP. Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:205–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvoisin RM, Villasana L, Pfankuch T, Raber J. Sex-dependent cognitive phenotype of mice lacking mGluR8. Behav Brain Res. 2010;209:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvoisin R, Zhang C, Pfankuch T, O'Connor H, Gayet-Primo J, Quraishi S, Raber J. Increased measures of anxiety and weight gain in mice lacking the group III metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR8. Eur J Neurosci. 2005:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvoisin RM, Zhang C, Ramonell K. A novel metabotropic glutamate receptor expressed in the retina and olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3075–3083. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-03075.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendt M, Bürki H, Imobersteg S, van der Putten H, McAllister K, Leslie JC, Shaw D, Hölscher C. The effect of mGlu(8) deficiency in animal models of psychiatric diseases. Genes Brain Behav. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00532.x. doi:10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossum EN, Lisowski MJ, Macey TA, Ingram SL, Morgan MM. Microinjection of the vehicle dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) into the periaquaductal gray modulates morphine nociception. Brain Res. 2008;1204:53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C, Cordova J, Levine LR, Morgan CA., 3rd Anxiolytic effects of a novel group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist ( LY354740) in the fear-potentiated startle paradigm in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168:446–454. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1444-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas H. Histamine potentiates neuronal excitation by blocking a calcium-dependent potassium conductance. Agents Actions. 1984;14:534–537. doi: 10.1007/BF01973865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helton D, Tizzano J, Monn J, Schoepp D, Kallman M. Anxiolytic and side-effect profile of LY354740: a potent, highy selectivem orally active agonist for group II metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Pharmaco Exp Ther. 1998;284:651–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim MM, Porreca F, Lai J, Albrecht PJ, Rice FL, Khodorova A, Davar G, Makriyannis A, Vanderah TW, Mata HP, Malan TP. CB2 cannaboid receptor activation produces antinociception by stimulating peripheral release of endogenous opiods. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3093–3098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409888102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaschka W, Feistel H, Ebert D. Reduced benzodiazepine receptor binding in panic disorder measured by iomazenil SPECT. J Psychiatr Res. 1995;29:427–434. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(95)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathuria S, Gaetani S, Fegley D, Valino F, Duranti A, Tontini A, Mor M, Tarzia G, La Rana G, Calignano A, Giustino A, Tattoli M, Palmery M, Cuomo V, Piomelli D. Modulation of anxiety through blockade of anandamide hydrolysis. Nat Med. 2002;9:76–81. doi: 10.1038/nm803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killcross S, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Different types of fear-conditioned behaviour mediated by separate nuclei within amygdala. Nature. 1997;388:377–380. doi: 10.1038/41097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klodzinska A, Bijak M, Tokarski K, Pilc A. Group II mGlu receptor agonists inhibit behavioural and electrophysiological effects of DOI in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;73:327–332. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00845-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang KC, Melia KR, Miserendino MJD, Falls WA, Campeau S, Davis M. Corticotropin-releasing factor: long-lasting facilitation of the acoustic startle reflex. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2303–2312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-06-02303.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden AM, Baez M, Bergeron M, Schoepp DD. Increased c-Fos expression in the centromedial nucleus of the thalamus in metabotropic glutamate 8 receptor knockout mice following the elevated plus maze test. Neuroscience. 2003a;121:167–178. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden AM, Bergeron M, Baez M, Schoepp DD. Systemic administration of the potent mGlu8 receptor agonist (S)-3,4-DCPG induces c-Fos in stress-related brain regions in wild-type, but not mGlu8 receptor knockout mice. Neuropharmacology. 2003b;45:473–483. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden AM, Johnson BG, Peters SC, Shannon HE, Tian M, Wang Y, Yu JL, Koster A, Baez M, Schoepp DD. Increased anxiety-related behavior in mice deficient for metabotropic glutamate 8 (mGlu8) receptor. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:251–259. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malan TP, Ibrahim MM, Deng H, Lin Q, Mata HP, Vanderah T, Porreca F, Makriyannis A. CB2 cannabinoid receptor-mediated peripheral antinociception. Pain. 2001;93:239–245. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monn JA, Valli MJ, Massey SM, Wright RA, Salhoff CR, Johnson BG, Howe T, Alt CA, Rhodes GA, Robey RL, Griffey KR, Tizzano JP, Kallman MJ, Helton DR, Schoepp DD. Design, synthesis, and pharmacological characterization of (+)-2-aminobicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-2,6-dicarboxylic acid ( LY354740): a potent, selective, and orally active group 2 metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist possessing anticonvulsant and anxiolytic properties. J Med Chem. 1997;40:528–537. doi: 10.1021/jm9606756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CA, Southwick SM, Grillon C, Davis M, Krystal JH, Charney DS. Yohimbine- facilitated acoustic startle reflex in humans. Psychopharmacology. 1992;110:342–346. doi: 10.1007/BF02251291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo E, Fu Y, Ji G, Maione S, Neugebauer V. Group III mGluR7 and mGluR8 in the amygdala differentially modulate nocifensive and affective pain behaviors. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:537–545. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne G, Neumann R. Effect of hypomagnesia on histamine H1 receptor-mediated faciliation of NMDA responses. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:199–204. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin JP, Duvoisin R. The metabotropic glutamate receptors: structure and functions. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00129-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raber J, Akana SF, Bhatnagar S, Dallman MF, Wong D, Mucke L. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function in Apoe−/− mice: Possible role in behavioral and metabolic alterations. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2064–2071. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-02064.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahn EJ, Zvonok AM, Thakur GA, Khanolkar AD, Makriyanic A, Hohman AG. Selective activation of cannabinoid CB2 receptors suppresses neuropathic nociception induced by treatment with the chemotherapeutic agen paclitaxel in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;327:584–591. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.141994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J, Curley J, Kaye J, Quinn J, Pfankuch T, Raber J. apoE isoforms and measures of anxiety in probable AD patients and Apoe−/− mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:637–643. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne P, Wingerson D, Radant A, Greenblatt D, Cowley D. Reduced benzodiazepine sensitivity in patients with panic disorder: comparison with patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and normal subjects. Am J Psychiatr. 1996;153:1444–1449. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.11.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saugstad JA, Kinzie JM, Shinohara MM, Segerson TP, Westbrook GL. Cloning and expression of rat metabotropic glutamate receptor 8 reveals a distinct pharmacological profile. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:119–125. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel S, Steinert H, Bockisch A, Hahn K, Schloesser R, Benkert O. Decreased benzodiazepine receptor binding in panic disorder measured by IOMAZENIL-SPECT. A preliminary report. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;244:49–51. doi: 10.1007/BF02279812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid S, Fendt M. Effects of the mGluR8 agonist (S)-3,4-DCPG in the lateral amygdala on acquisition/expression of fear-potentiated startle, synaptic transmission, and plasticity. Neuropharmacol. 2006;50:154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stachowicz K, Kłak K, Pilc A, Chojnacka-Wójcik E. Lack of the antianxiety-like effect of (S)-3,4-DCPG, an mGlu8 receptor agonist, after central administration in rats. Pharmacol Rep. 2005;57:856–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundstrom I, Ashbrook D, Backstrom T. Reduced benzodiazepine sensitivity in patients with premenstrual syndrome: a pilot study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1997;22:25–38. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(96)00035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson C, Bures M, Johnson M, Linden A-M, Monn J, Schoepp D. Metabotropic glutamate receptors as novel targets for anxiety and stress disorders. Nature Rev Drug Disc. 2005;4:131–144. doi: 10.1038/nrd1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Geyer MA, Vale WW, Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor potentiates acoustic startle in rats: blockade by chlordiazepoxide. Psychopharmacology. 1986;88:147–152. doi: 10.1007/BF00652231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Britton KT, Koob GF. Potentiation of acoustic startle by corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and by fear are both reversed by α-helical CRF (9–14) Neuropsychopharmacology. 1989;2:285–292. doi: 10.1016/0893-133x(89)90033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas NK, Wright RA, Howson PA, Kingston AE, Schoepp DD, Jane DE. (S)-3,4-DCPG, a potent and selective mGlu8a receptor agonist, activates metabotropic glutamate receptors on primary afferent terminals in the neonatal rat spinal cord. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:311–318. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tizzano J, Griffey K, Schoepp D. The anxiolytic action of mGlu2/3 receptor agonist LY354740, in the fear-potentiated startle model in rats is mechanisticlly distinct from diazepam. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;73:367–374. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00850-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorobjev V, Sharanova I, Walsh I, Haas HL. Histamine potentiates N-methyl-D-apartate responses in acutely isolated hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1993;11:837–844. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]