Abstract

Background

Since 2003, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) has been the most ambitious initiative to address the global HIV epidemic. However, PEPFAR’s effect on HIV-related outcomes is unknown.

Objective

To assess PEPFAR’s impact on HIV-related deaths, the number of people living with HIV, and prevalence in Africa.

Design

Comparison of trends before and after the initiation of PEPFAR’s activities in the African focus countries with other African countries.

Setting

Twelve African focus countries and 29 controls with a generalized HIV epidemic from 1997–2007.

Observations

451 country-year observations.

Intervention

A 5-year, $15 billion program for HIV treatment, prevention, and care that started in late 2003.

Measurements

HIV-related deaths, the number of people living with HIV, and prevalence.

Results

Between 2004 and 2007, the annual change in the number of HIV-related deaths was lower by 10.5% in the focus countries compared to controls (p=0.001). The difference in trends between the group before 2003 was not significant. The annual growth in the number of people living with HIV was 3.7% slower in the focus countries compared to controls from 1997–2002 (p=0.05), but during PEPFAR’s activities the difference was no longer significant. The difference in the change in HIV prevalence was not significantly different throughout the study period. These estimates were stable after a sensitivity analysis.

Limitations

The selection of the focus countries was not random, and limits the generalizability of the results.

Conclusions

We find evidence that, after four years of activity, HIV-related deaths declined in PEPFAR’s focus countries relative to sub-Saharan African controls, but trends in adult prevalence were not different. Assessing epidemiologic effectiveness should be part of PEPFAR’s evaluation programs.

INTRODUCTION

Alleviating the burden of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa is one of the great challenges of our time (1). HIV is the leading cause of death in Africa, and is responsible for a reduction in life expectancy in many countries (2). Available resources for HIV in less developed countries expanded more than five-fold since the Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2001 (3, 4), but the expansion has not been evenly distributed. Since 2003, the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) provided the majority of its $18.8 billion budget to 15 focus countries – 12 of them in Africa – for HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment, and care (5, 6). While the criteria for selecting focus countries were not explicit, they were related the burden of disease, the focus countries’ governmental commitment to fighting HIV, administrative capacity, and a willingness to partner with the US government. Nearly half of PEPFAR’s resources were spent on antiretroviral drugs and treatment infrastructure, and about a fifth was spent on prevention programs, of which one third was earmarked for abstinence-only programs. Through its various activities, PEPFAR aimed to support the provision of life-saving antiretrovirals to 2 million people and prevent 7 million HIV infections in the focus countries. Among the three major funders of HIV/AIDS programs – the others are The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria and the World Bank – PEPFAR is unique in its distinctive approaches and disproportionate funding of a few countries (7–10).

In July, 2008, the US Senate reauthorized PEPFAR with a $48 billion budget for the next five years, including a broader emphasis on strengthening health systems (11). The US leadership in the battle against HIV has been one of its most important legacies in Africa (12, 13). However, despite the substantial financial commitment and the important role PEPFAR plays abroad, no quantitative evaluation of the program’s outcomes has been completed. The original legislation mandated a short-term evaluation that was completed by the Institute of Medicine in 2007 (14). Their report scrutinized PEPFAR’s ability to meet its targets for delivery of prevention, treatment, and care services in the focus countries, and found that within 2 years, PEPFAR supported expansion of HIV/AIDS activities in the focus countries; however, it did not evaluate health-related outcomes such as HIV mortality, incidence, or prevalence.

The number of human lives affected and the financial stakes make it essential to assess the impact of PEPFAR's investment in Africa. Although the full impact of PEPFAR may not be felt for years, an ongoing evaluation of programmatic outcomes is central to the direction of future policies. We undertake the first quantitative evaluation of HIV-related outcomes in the focus countries compared with other countries in sub-Saharan Africa with a generalized HIV epidemic.

METHODS

Country Selection

All countries of central, east, west, and south Africa and the island nations of Cape Verde, Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Seychelles were eligible for this analysis. We excluded countries if they did not have epidemiologic data or if their HIV epidemic was not generalized. Generalized epidemic was defined as HIV prevalence of over 1% in antenatal clinics and a predominantly heterosexual mode of transmission (9, 15). The countries which PEPFAR selected as focus countries were examined as an intervention group, while all other African countries with a generalized HIV epidemic were designated controls.

Data Sources

The joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) has monitored the Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS by working with individual countries to measure the global epidemiology of HIV/AIDS (16). We used country and year epidemiologic data obtained through UNAIDS from 1997 to 2007 as the outcome variables for this study. UNAIDS determines the prevalence trends using sentinel and population based surveys. The prevalence estimates, vital registry data, and model-based calculations are then used to determine mortality and the number of people living with HIV. All the estimates are given uncertainty bounds which depend on the quality of the primary data and the strength of the assumptions used in the estimation process (17).

We obtained data on Global Fund allocation of resources, population structure, governance indicators, life expectancy, and per-capita gross domestic product from publicly available databases (10, 18–20).

Study Period and Outcomes

We chose two study periods for this analysis: an early period, from 1997–2002, prior to the onset of PEPFAR; and a late period, from 2004–2007, during PEPFAR’s activities. We excluded 2003, the watershed year when PEPFAR’s operations were getting organized. Three outcomes of interest were examined: HIV prevalence among adults age 15–49, number of deaths due to HIV/AIDS, and the number of adults living with HIV. We used these indicators as outcomes because they reflect the most consistent measures for cross-country comparisons available over time. The indicators are publicly available (21).

Statistical Analysis

We compared trends of the epidemic outcomes between the focus and control countries during the two time periods noted above. The early period represented the trends of the epidemic absent PEPFAR activity, while the analyses of the late study period represented the trends during PEPFAR’s activity. We tested the hypothesis that the epidemic in the focus countries showed greater improvement (or lesser worsening) than in the control countries after the onset of PEPFAR’s activities. We included the earlier time period in order to separate the effects of PEPFAR from the natural course of the epidemic and any between-country differences; that is, we wanted to compare not only the relative trends after PEPFAR, but also any changes in the relative trends after the onset of PEPFAR.

We analyzed the trends using a fixed-effects model for longitudinal data (22). We fixed the time and country effects and clustered by country to account for within-country correlation of observations over time (23). The year, PEPFAR designation as a focus country, and an interaction term between them were included as predictors in the unadjusted model. Except for prevalence rates, the outcomes we examined depend on the size of the population. To account for that, we examined the percentage change in the outcomes of interest by using log transformations of the outcomes (24). For prevalence rates, we report the difference between the focus and control countries of the change in prevalence rather than the difference in percentage change. We report the interaction term coefficient, which estimates the difference in the trends between the focus and control countries. For example, a coefficient of −2% in the number of deaths from 2004 to 2007 suggests that, during that period, the percentage change in the number of deaths was 2% less in the focus countries than in the controls (which means that deaths were rising more slowly or descending more rapidly, depending on the overall trend). We used Stata 9.2 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) for all analyses.

In adjusted analyses, we accounted for baseline HIV prevalence (1997), population size, life expectancy, per-capita gross domestic product, the amount of funding from the Global Fund for HIV per capita, and four measures of governance from the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators: control of corruption, political stability, rule of law, and government effectiveness (20). The Indicators measure the quality of governance in over 200 countries based on 35 data sources from 32 organizations. They have been available since 1996, and are widely used in development research (25, 26). We also changed the model structure to allow for random year effects. Since none of these additional analyses changed the direction or significance of the relative effect of PEPFAR, we report the results of the unadjusted analyses.

To account for the assumptions and imprecision in the UNAIDS data, we did two different sensitivity analyses. First, we performed a Monte Carlo process where the outcome variable was drawn randomly within the uncertainty bounds for each country-year, and the analysis was repeated 1,000 times. We also performed a sensitivity analysis where we randomly selected groups of “focus” countries and ran the analysis 1,000 times to verify our analyses were not biased in favor of finding significant differences (23).

This work was supported in part by a training grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The funding agency had no part in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

RESULTS

Baseline Parameters

We examined twelve PEPFAR focus countries and 29 control countries from sub-Saharan Africa for the analysis. Tables 1 and 2 show the selected countries and their baseline characteristics, respectively. The focus countries had a significantly higher average population (37 vs. 11.7 million people, p<0.01), but there was no difference in the life expectancy of men or women. The per-capita disbursements from the Global Fund were slightly more generous in the control countries, but the annual per-capita gross domestic product was significantly lower in those countries ($1,935 vs. $4,094). The focus countries ranked higher than the controls on all governance indicators – significantly higher in government effectiveness – at the time of PEPFAR’s start. The adult HIV prevalence was higher in the focus countries throughout both study periods (p<=0.05).

Table 1.

Focus and control countries

| Focus Countries | Control Countries | |

|---|---|---|

| Botswana | Angola | Guinea |

| Cote d'Ivoire | Benin | Guinea-Bissau |

| Ethiopia | Burkina Faso | Lesotho |

| Kenya | Burundi | Liberia |

| Mozambique | Cameroon | Madagascar |

| Namibia | Central African Republic | Malawi |

| Nigeria | Mali | |

| Chad | ||

| Rwanda | Niger | |

| Congo | ||

| South Africa | Senegal | |

| Tanzania | Democratic Republic of Congo | Sierra Leone |

| Uganda | Djibouti | Somalia |

| Zambia | Eritrea | Sudan |

| Gabon | Swaziland | |

| Gambia | Togo | |

| Ghana | Zimbabwe |

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics and baseline HIV epidemic estimates

| Parameter | Focus Countries, mean (SD) | Control Countries, mean (SD) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 12 | 29 | ||

| Population (2007, millions)(18) | 37.0 (40.1) | 11.7 (13.0) | <0.01 | |

| Life Expectancy (years)(9) | ||||

| Male | 45.7 (4.1) | 46.9 (7.1) | 0.58 | |

| Female | 47.6 (4.4) | 49.6 (7.7) | 0.40 | |

| Gross Domestic Product Per Capita (2007USD)(19) |

4,094 (5,323) | 1,935 (1,455) | 0.05 | |

| Global Fund Disbursement per capita(2007USD)(10) |

3.8 (4.0) | 4.7 (7.4) | 0.70 | |

| Governance Indicators, 2003(20) | ||||

| Control of Corruption |

33.6 (23.6) | 25.9 (18.4) | 0.27 | |

| Rule of Law | 32.2 (20.4) | 23.6 (18.5) | 0.20 | |

| Government Effectiveness |

37.2 (22.3) | 21.3 (16.2) | 0.02 | |

| Political Stability |

29.8 (24.5) | 29.3 (19.8) | 0.95 | |

| HIV deaths per 1,000 population | ||||

| 1997 | 2.6 (1.8) | 1.3 (2.4) | 0.10 | |

| 2007 | 3.1 (2.0) | 2.2 (3.1) | 0.36 | |

| Adult Prevalence (%) | ||||

| 1997 | 9.5 (5.9) | 4.7 (7.1) | 0.05 | |

| 2007 | 9.7 (7.1) | 4.5 (6.5) | 0.03 |

Outcome Measures

Number of Deaths from HIV/AIDS

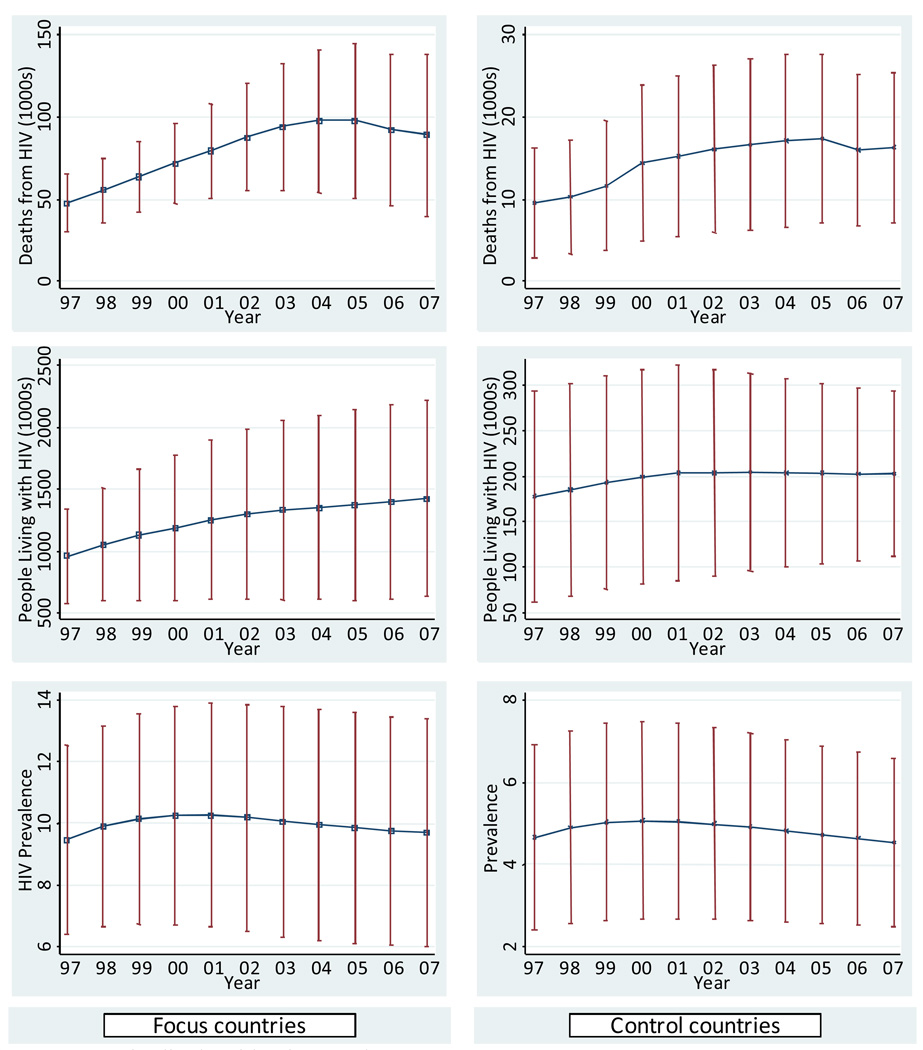

The number of deaths from HIV/AIDS rose in the first period, but declined in the second period in the focus countries and leveled off in the controls (Figure 1). Prior to 2003, the annual percent increase in the number of deaths due to HIV was 3.5% higher in the control countries, but that difference was not significant (p=0.22). During the second study period, however, the death toll from HIV decreased much more rapidly in the focus countries compared to the controls. During this period, the difference in the percentage change was 10.5% lower in the focus countries (p=0.001, Table 3). Figure 2 shows that the difference in death rates between the groups of countries started after 2003, and was most pronounced between 2005 and 2006, after nearly 3 years of PEPFAR activities.

Figure 1. Longitudinal Epidemic Trends.

Epidemiologic trends of the study outcomes for the focus countries and control countries. The means of the three study outcome measures are shown, along with 95% confidence intervals.

Table 3.

Differences in outcomes between focus and control countries during early and late study periods

| Outcome Measure | Mean Annual Percentage Change during period* | Difference in annual % change, focus countries relative to controls (95% CI)† |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus Countries | Control countries | |||

| Number of deaths from HIV/AIDS |

||||

| 1997–2002 | 14.1% | 17.2% | −3.5 (−9.1 – 2.2) | 0.22 |

| 2004–2007 | −6.3% | 1.2% | −10.5 (−16.6 – −4.4) | 0.001 |

| Number of people living with HIV |

||||

| 1997–2002 | 4.7% | 8.9% | −3.7 (−7.4 –0) | 0.05 |

| 2004–2007 | 1.2% | 3.1% | −1.7 (−4.0 – 0.5) | 0.12 |

| Adult HIV Prevalence‡ | ||||

| 1997–2002 | 0.14% | 0.07% | 0.05 (−0.3 – 0.41) | 0.76 |

| 2004–2007 | −0.09% | −0.1% | 0.01 (−0.18 – 0.19) | 0.95 |

Calculated from primary data as the mean of the percentage change in the outcome between consecutive years. Data is available on UNAIDS website

Results from an unadjusted regression analysis of the difference in annual percentage change between the groups of countries

Changes in prevalence are reported directly rather than transformed to percentage change. For example, an increase in prevalence from 5% to 6% counts as a 1% change rather than a 20% increase

Figure 2. Differences in Outcomes Between Groups of Countries Over Time.

Difference in percentage change in the outcome measures over time between the focus and control countries. Each data point represents the difference in the percentage change from the previous year to the current. That is, each point represents for outcome X in year t. Negative numbers mean the outcome dropped faster (or increased more slowly) in the focus countries. Deflections away from zero suggest that the differences became more pronounced, while deflections towards zero mean that the trends were becoming more similar. The vertical line represents the transition period around 2003, when PEPFAR was getting organized.

* PLWHA – people living with HIV/AIDS

Number of People Living with HIV/AIDS

The number of people living with HIV/AIDS rose in the focus and control countries throughout both study periods (Figure 1). The annual percent change in the number was lower by 3.7% in the focus countries during the early period (p=0.05, Table 3). In the late period, during PEPFAR’s activities, the annual percent rise in the number of people living with HIV/AIDS was slower in both groups of countries. However, the difference (1.7% lower in the focus countries) was no longer significant (p=0.12). That is, between the early and late periods the focus countries experienced a relative acceleration in the number of people living with HIV/AIDS compared with the control countries. Figure 2 shows the difference in the annual percent change diminishing (getting less negative) after 2003, while the difference in the number of people living with HIV/AIDS was negative (rise was slower in the focus countries) before 2003.

HIV Adult Prevalence

The HIV prevalence in both groups of countries peaked by 2002 (Figure 1). Before 2003, the prevalence rose faster in the focus countries compared to the controls (0.05% faster annually), an insignificant difference. During PEPFAR’s activities, the difference in prevalence change between the groups was nearly 0% (p=0.95), as both groups of countries experienced a gradual decline of about 0.1% annually in the HIV prevalence in the adult population. Figure 2 shows that the difference in the adult prevalence diminished throughout the early period, and remained stable around 0% difference after 2003. Additional details on the regression models are provided in Supplementary Tables 1–6.

Sensitivity Analysis

To assess the stability of our analyses, we used the uncertainty bounds provided by UNAIDS to select values for the outcome measures. We used a uniform distribution to draw a value for the outcome variables, avoiding assumptions about the true value. We then used the randomly picked value for each country-year as the value for the regression. This process was repeated 1,000 times, and we collected the mean of the coefficients and p-values. Using this procedure, the difference in the annual percent change in the deaths due to HIV/AIDS was −2.0% during the early period (p=0.29), and −9.7% in the late period (p=0.02) in the focus countries compared to controls. We obtained a significant difference in deaths from HIV in 90.7% of the iterations in the late period, but only 3.7% of the iterations in the early period. The full results of the sensitivity analysis is provided in Supplementary Table 7.

Our second procedure for verifying the stability of our results, where we randomly selected groups of countries to serve as “focus” countries for the analysis, showed that any significant differences, especially in the number of deaths, disappeared.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the impact of PEPFAR by comparing changes in three outcome measures between the focus countries and other countries with a generalized HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa, before and after the onset of PEPFAR. Our results show that after four years of activity, there is evidence to suggest that PEPFAR was associated with a decrease in the death toll due to HIV/AIDS, and may be linked to a relative increase in the number of people living with HIV/AIDS. We also see no evidence that PEPFAR was associated with changes in adult HIV prevalence in the focus countries compared to other sub-Saharan African countries.

The reduction in HIV-related deaths is likely the result of improved treatment and care of HIV-infected individuals in the focus countries, especially the scale-of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Increases in antiretroviral therapy coverage occurred disproportionately in the focus countries during the past 5 years (9), and nearly half of PEPFAR’s expenditures are dedicated to purchasing antiretrovirals, constructing treatment infrastructure, and providing antiretroviral services (28). Around the time of PEPFAR’s launch, other governmental and multinational organizations, most notably the Global Fund, also scaled up their activities to combat HIV, and may have contributed to the decline in HIV deaths seen across the continent. However, the added infusion of funding for antiretrovirals in the focus countries made an appreciable impact on the deaths from HIV and speaks to the power of antiretrovirals to improve survival in a relatively short period of time.

We observe a relative acceleration in the number of people living with HIV/AIDS in the focus countries relative to controls during PEPFAR’s activities. While long-term goals may target reductions in the size of infected populations, this increase probably reflects the decreasing death toll and may have several public health spillover benefits. For example, infected adults who live longer may be able to support their children and dependent elderly, reducing the burden of orphans and elderly care.

Changes in prevalence are complex and depend on the rate of new infections, deaths due to HIV/AIDS, and changes in the size of the population. We see no evidence that prevalence trends in the focus countries were different from those in the control countries during PEPFAR’s activities. To affect a reduction in HIV prevalence, the combined effect of reduced HIV incidence and increased population size has to offset the reduction in deaths from HIV/AIDS. While it may be too early to observe these changes, it is important to follow this trend for several reasons: measurement of prevalence is standardized in many countries, longitudinal trends through sentinel sites are widely available, and it is a key determinant of infection risk (29). Reduction in prevalence that may be attributable to PEPFAR would be a consequential accomplishment for the next five years of PEPFAR.

As the number of people on antiretroviral therapy and the deaths averted in the focus countries continue to increase, the cost of providing treatment is expected to increase as well. Projections of financial resources needed to sustain the treatment scale-up suggest that even with PEPFAR’s increased commitment, the gap between the available funds and those needed will continue to increase unless the incidence of HIV in Africa is substantially reduced (3). Striking the right balance between treatment and prevention with insufficient resources for the burden of the epidemic is a major challenge for comprehensive care programs such as PEPFAR.

Monitoring impact will have important implications for PEPFAR’s future as well as that of other organizations that are operating with poor information about the effectiveness and efficiency of their programs. In a recent report, the Institute of Medicine drafted general considerations for evaluating PEPFAR’s impact, including HIV prevalence, mortality, and incidence, as well as broader metrics such as system capacity, economic development, and health status (30). Incidence, in particular, has not been directly estimated in Africa, and the measurement techniques are increasingly available (31). Impact evaluations are difficult, but rigorous methods adopted specifically to resource-limited regions, including randomization into program entry, are commonly used in other disciplines (32).

We evaluated the contribution of PEPFAR to the abatement of the epidemic in the focus countries, which has implications for the program’s economic efficiency. By the end of 2007, PEPFAR spent more than $6 billion on HIV care, prevention, and treatment in the 12 focus countries examined in this study. In those countries, a reduction in the death rate of 9.5% implies about 1.1 million deaths were averted due to PEPFAR’s activities. This large benefit cost about $2,700 per death averted, assuming PEPFAR directed half of its budget towards treatment. This is a rough estimate, and it may change as the treatment infrastructure and supply chains become more established, but it could allow an evaluation of the program’s efficiency. A formal cost-effectiveness analysis will also allow a comparison with other interventions for HIV in Africa (33).

Our study has several methodological limitations. First, we use UNAIDS data that is partly derived with the help of mathematical models. We deal with this limitation by doing a sensitivity analysis using the uncertainty bounds, which take into account the imprecision in both the primary data and the model estimates. We use a resampling procedure that is agnostic about the exact values of outcomes within the uncertainty bounds, and strengthens the results of the primary analysis. It is also possible that the data in the focus countries is more reliable than in the controls. This is unlikely to change the results, as PEPFAR’s support for monitoring and evaluation programs was minor, and this effect is likely to be small.

Second, we perform cross-country comparisons between groups of countries which were not picked at random and with significant baseline differences. We address this partly by controlling for observable potential sources of bias such as population, gross domestic product, aid for HIV from other sources, and governance indicators. Because the focus countries were not selected randomly, and we cannot fully observe the differences between the groups, our measured effects may be specific to the countries and years of the study. That is, we cannot fully generalize the results to other countries or other time periods. If PEPFAR had chosen a different set of focus countries or operated at a different time, we may have observed a different impact.

Third, it is possible that the observed difference in deaths after 2004 results from a difference in the phase of the epidemics in the study countries. That is, if the epidemic in the focus countries was more mature than the controls, then the observed relative reduction in deaths could occur without any intervention or program. However, the lack of difference in HIV deaths prior to 2003 argues against this possibility as an explanation of the results.

While the Institute of Medicine scrutinized PEPFAR’s operations, it failed to evaluate outcomes that are central to the epidemic’s prevention and treatment efforts. The commitment of funds by the US government is commendable, but it is crucial to ascertain that the Plan is effective, and that the investment is cost-effective. As PEPFAR enters its next funding period, evaluating outcomes will highlight the areas which are successful and those which are not making an appreciable impact. This analysis shows the success of PEPFAR to avert HIV-related deaths in a relatively short period of time. It also underscores the importance of a continued outcome-based evaluation of this essential and expensive intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Karen Stanecki of UNAIDS for help with providing and clarifying the data used in this study and Grant Miller, PhD and Kanaka Shetty, MD MS of the Center for Health Policy at Stanford for methodologic contributions.

Grant Support: Dr. Bendavid is supported by a training grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Bhattacharya is supported by the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Potential Financial Conflicts of Interest: None disclosed.

Author Contributions: Conception and design: E. Bendavid

Analysis and interpretation of the data: E. Bendavid, J. Bhattacharya.

Drafting of the article: E. Bendavid.

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: E. Bendavid, J. Bhattacharya.

Final approval of the article: E. Bendavid, J. Bhattacharya.

Statistical expertise: E. Bendavid, J. Bhattacharya.

Collection and assembly of data: E. Bendavid.

Author Contribution and Conflicts of Interests

Eran Bendavid: I declare that I participated in originating the concept, in conducting the data collection, and data analysis. I did most of the writing of the paper, including the final revision. I had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. I have no conflict of interests.

Jayanta Bhattacharya: I declare that I participated in elucidating the original concept, in the data analysis, critical review of the results, and revising the manuscript. I have seen and approved the final version and I have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.The Copenhagen Consensus Center. 2008 Accessed at www.copenhagenconsensus.com on September 1 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piot P, Bartos M, Ghys PD, Walker N, Schwartlander B. The global impact of HIV/AIDS. Nature. 2001;410(6831):968–973. doi: 10.1038/35073639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS. Financial Resources Required to Achieve Universal Access to HIV Prevention, Treatment, Care and Support. 2007

- 4.United Nations: Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly. 2001 August 2; Accessed at http://www.un.org/ga/aids/docs/aress262.pdf on June 12, 2008.

- 5.US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. Making A Difference: Funding. Accessed at http://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/80161.pdf on Nov 29, 2008.

- 6.The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. Five-Year Strategy. Accessed at http://www.state.gov/s/gac/plan/c11652.htm on June 28, 2008.

- 7.President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) Accessed at http://www.avert.org/pepfar.htm on June 28, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Görgens-Albino M, Mohammad N, Blankhart D, Odutolu O. (The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank). The Africa Multi-Country AIDS Program 2000–2006: Results of the World Bank’s Response to a Development Crisis. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNAIDS. (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS). Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. 2008

- 10.The Global Fund: Pledges and Contributions. 2008 Accessed at http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/funds_raised/pledges on Jun 8, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Sadr WM, Hoos D. The President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief--is the emergency over? N Engl J Med. 2008;359(6):553–555. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0803762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stolberg S. In Global Battle on AIDS, Bush Creates Legacy. The New York Times. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bristol N. US Senate passes new PEPFAR bill. Lancet. 2008;372(9635):277–278. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sepúlveda J, Carpenter C, Curran J, et al. ( Institute of Medicine of the National Academies). PEPFAR Implementation: Progress and Promise. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghys PD, Brown T, Grassly NC, et al. The UNAIDS Estimation and Projection Package: a software package to estimate and project national HIV epidemics. Sexually transmitted infections. 2004;80 Suppl 1:i5–i9. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.010199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.UNAIDS. Monitoring the Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS : Guidelines on Construction of Core Indicators. 2005

- 17.Ghys PD, Walker N, McFarland W, Miller R, Garnett GP. Improved data, methods and tools for the 2007 HIV and AIDS estimates and projections. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84 Suppl 1:i1–i4. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.032573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Census Bureau International Database Population Pyramids. Accessed at http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb/pyramids.html on November 27, 2008.

- 19.The World Bank. 2008 Accessed at web.worldbank.org on March 28, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Bank. The Worldwide Governance Indicators project. 2008 Accessed at http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.asp on January 3 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.UNAIDS. 2008 Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic: Epidemiology Information. 2008 Accessed at http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2008/2008_Global_report.asp on November, 2008.

- 22.Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. USA: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainthan S. How Much Should We Trust Differences-in-Differences Estimates? The Quarterly journal of Economics. 2004;119(1):249–275. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cole TJ. Sympercents: symmetric percentage differences on the 100 log(e) scale simplify the presentation of log transformed data. Statistics in medicine. 2000;19(22):3109–3125. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001130)19:22<3109::aid-sim558>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sachs JD, McArthur JW, Schmidt-Traub G, et al. Ending Africa's Poverty Trap. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 2004:117–240. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Easterly W. Inequality does cause underdevelopment: Insights from a new instrument. Journal of Development Economics. 2007;84(2):755–776. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Annual Report Transparency International. 2007 Accessed at http://www.transparency.org/ on on June 29, 2008.

- 28.Office of the United States Global AIDS Coordinator. The Power of Partnerships: The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief Third Annual Report to Congress. 2007

- 29.Anderson RM, May RM. Epidemiological parameters of HIV transmission. Nature. 1988;333(6173):514–519. doi: 10.1038/333514a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen C, Orza M, Patel D. (Institute of Medicine of the National Academies). Design Considerations for Evaluating the Impact of PEPFAR: Workshop Summary. 2008. (Rappotreurs) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV Incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duflo E, Kremer M. Use of Randomization in the Evaluation of Development Effectiveness. In: Pitman G, Feinstein O, Ingram G, editors. Evaluating Development Effectiveness. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Creese A, Floyd K, Alban A, Guinness L. Cost-effectiveness of HIV/AIDS interventions in Africa: a systematic review of the evidence. Lancet. 2002;359(9318):1635–1643. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08595-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.