Abstract

In the Andean region of Latin America over one million adolescent girls get pregnant every year. Adolescent pregnancy (AP) has been associated with adverse health and social outcomes, but it has also been favorably viewed as a pathway to adulthood. AP can also be conceptualized as a marker of inequity, since it disproportionately affects girls from the poorest households and those who have not been able to attend school.

Using results from a study carried out in the Amazon Basin of Ecuador, this paper explores APs and adolescents' sexual and reproductive health from a rights and gender approach. The paper points out the main features of a rights and gender approach, and how it can be applied to explore APs. Afterward it describes the methodologies (quantitative and qualitative) and main results of the study, framing the findings within the rights and gender approach. Finally, some implications that could be generalizable to global reserach on APs are highlighted.

The application of the rights and gender framework to explore APs contributes to a more integral view of the issue. The rights and gender framework stresses the importance of the interaction between rights-holders and duty-bearers on the realization of sexual and reproductive rights, and acknowledges the importance of gender–power relations on sexual and reproductive decisions. A rights and gender approach could lead to more integral and constructive interventions, and it could also be useful when exploring other sexual and reproductive health matters.

Keywords: adolescent pregnancy, reproductive and sexual rights, gender relations, gender structures, agency

In the Andean region of Latin America – comprising Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela, over one million girls aged 15–19 are pregnant or mothering (1). Adolescent fertility rates range from 61 births per 1,000 girls aged 15–19 in Chile to 92 births in Venezuela. While total fertility rates have been declining, adolescent fertility rates have experienced little change, and in countries such as Colombia and Ecuador, they have even increased. Adolescent fertility rates are higher among girls than among boys – in fact, many adolescent pregnancies (APs) are fathered by much older men, and there are marked differences between socioeconomic status and educational levels: i.e. in Ecuador, while 28% of girls from poor households get pregnant during adolescence, only 11% from the richest do; while 52.3% illiterate girls get pregnant, only 11% with secondary education do (2).

Worldwide, APs have been associated with negative health and socioeconomic outcomes. Maternal mortality and morbidity increases among the youngest adolescent mothers, and adolescent motherhood has been associated with higher risk of infant morbidity and mortality and lower socioeconomic and educational attainment (3–8). However, AP can also bear positive connotations; it could be configured as a way to gain status, a turning point to a healthier behavior, or even become an escape from abusive families (9–13).

Adolescents' sexual and reproductive health has gained space in public policies in the Andean region. All the countries have adopted Adolescents' Codes or Laws, following the principles of the Convention of the Rights of Children, and some have even promulgated Youth Laws. The promotion of adolescents' sexual and reproductive health has flourished within the Ministries of Health, and there have been advances on sex education policies and programs. However, the United Nations Committee for the Rights of Children has expressed concern regarding the high prevalence of AP, and has highlighted barriers limiting adolescents' access to sexual and reproductive health services and sex education (14). As a response to these concerns, the Ministries of Health of the six Andean countries launched, in 2007, the Andean Plan for AP Prevention, a 5-year plan aimed to promote adolescents' rights, and to improve their access to health services, including sexual and reproductive health care.

Research on APs in Latin America is not as profuse as in Europe or the USA. Existing studies analyze risk factors for APs, obstetric, and neonatal consequences (5, 8, 15–20), and there are some qualitative articles exploring life experiences of pregnant and mothering adolescents (11, 21). Research comes from big urban areas and hospitals and, following a global trend, mainly approaches APs from a biomedical perspective. It seldom tackles the connections between sexual and reproductive rights and APs or takes a gender perspective.

This article explores APs from a rights and gender approach, under the assumption that pregnancy and motherhood would be better understood as events embedded into the broader area of girls' sexual and reproductive health and gender relations. To exemplify this statement, this article uses previous research on APs conducted in a remote area of the Amazon Basin of Ecuador, and extracts some implications that could be generalizable at a broader level.

A rights and gender approach to adolescent pregnancies (APs)

A rights approach

Women's right to health was not explicitly recognized until 1979, in the Convention of the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women – CEDAW (22, 23). That recognition implies that every woman is free to make decisions that benefit her well-being, and that she is entitled to a system of health protection. Women, as rights-holders, have the right to make free decisions regarding their sexuality and reproduction; and this means not merely the legal right to act, but the actual capability to act freely, the capability to intervene or refuse to do it, the capability to influence structures and make a difference: this is closely related to Giddens's conceptualization of agency (24, 25). At the same time, states – as duty-bearers – have the responsibility to implement a system of health protection that includes the provision of an adequate network of services, but also the reduction of inequities that may curtail the opportunities of certain groups to stay healthy – the so called social determinants of health (26–29).

In Cairo's Conference of Population and Development, reproductive and sexual rights were finally incorporated as part of the right to health. That constituted a shift in the way reproductive health was approached: leaving behind population control policies, the focus moved toward the promotion of individual's capability to make autonomous and informed decisions regarding sexuality and reproduction (22, 30–33).

The rights approach to sexual and reproductive health goes beyond the provision of reproductive and sexual health care – family planning, maternal health, promotion of healthy sexuality, prevention and management of reproductive infections and morbidities, prevention and management of violence against women and sexual violence (30); it implies incorporating the principles of human rights to sexual and reproductive health. Sexual and reproductive rights' exercise depends on the individual's freedom-agency to make genuinely free decisions regarding one's health and body (28, 31, 34), and states' capability to put into practice a system of health protection that includes sexual and reproductive health services, and a healthy environment regarding the social determinants of reproductive and sexual health (28, 35, 36). State's obligation should not be limited to judging and ruling, but should also include investing in policies and services that promote individuals' capability to exercise their rights (23, 26, 37).

Under the rights approach, services should fulfill the criteria of availability, accessibility, acceptability, good quality, and relevance (28, 38, 39). Another key principle is accountability, which implies state's obligation to develop mechanisms that enable citizens and human rights bodies, to monitor and evaluate progress (25–28, 40). Participation in designing, planning, and implementing sexual and reproductive health policies and programs is both a rights' principle and a means for ensuring the relevance and impact of policies and programs (28, 31, 39).

A gender approach

In this study, a gender approach aimed to draw attention to the effect of unequal gender relations on girls' capability to exercise their sexual and reproductive rights, and to explore opportunities for strengthening girls' agency, and for challenging gender structures that subordinate young women toward adults and men.

Connell's definition of gender as ‘the structure of social relations that centers on the reproductive arena, and the set of practices (governed by this structure) that brings reproductive distinctions between bodies into social processes’ (41) was particularly useful. Connell challenges the gender role theory, since gender is not fixed but always under construction in relation to others at the individual level, institutional level, and social level. Individuals chose to do gender (42), they make decisions within gender relations, and this dynamic conceptualization of gender leaves room for agency (41, 43). However, agency is not exerted in a vacuum with an unlimited number of choices; it is exerted within gender structures that strongly influence individual practices (41, 43). Gender regimes of institutions and the gender order may constrain, or enhance, individuals' gender practices (41, 43). But also individuals, by their gender relations, might influence gender regimes and the gender order – although probably in a very limited way. The importance of the intersection of gender with other variables such as class, ethnicity, or age, is also paramount (41, 42, 44, 45).

In the Latin American context, the machismo–marianismo system still strongly influences gender relations (46–50). While machismo has been defined as a ‘cult around masculinity intrinsically related to power: the will and capacity to dominate others, men as well as women’ (46), marianismo conceptualizes women as passive, modest, and submissive; it idealizes motherhood and repudiates women's sexual drives (48, 49, 51).

Exploring adolescent pregnancies (APs) from a rights and gender approach

Despite the connections between APs and sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) and gender relations, research on APs seldom considers those issues. The risk approach still dominates (14, 52), and consequently the results reinforce a negative conceptualization of adolescents and young people, focus on pregnancy as an isolated event, and place the main responsibility for AP prevention on the adolescent girls themselves.

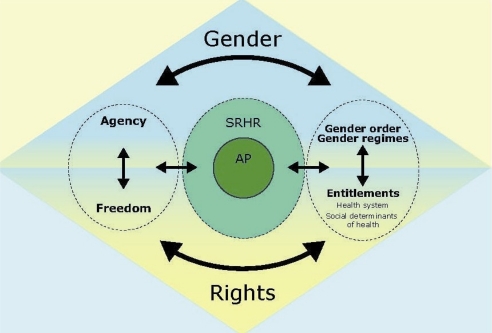

The present study is grounded on the assumption that in order to understand AP, we first need to embody it in a female body (53). Pregnancy is connected with many phenomena that belong to the sphere of sexual and reproductive health: sexual intercourse, sexual relations, contraceptive use, maternal care, abortion, reproductive morbidities, and sexual abuse among others. Exploring all those interconnected events may help us to better understand the experience of pregnancy. Moreover, all those events occur in a particular time and place, and those circumstances affect not only one isolated female body but many others that share the same time and setting, transforming an individual experience into a public health issue. In Fig. 1 this is represented by placing the smaller circle representing AP within the wider circle of SRHR.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework. Adolescent pregnancies from a rights and gender approach (taken from the PhD thesis).

AP is an individual experience, and may differ greatly from one girl to another. It could have been a wanted event, an unexpected surprise, or even the consequence of forced sexual intercourse. How each girl experiences her pregnancy is entangled with other sexual and reproductive health experiences such as contraceptive negotiation and use, power to make decisions, sexuality, and affection. It is also entangled with her agency-freedom to make decisions regarding her sexuality and reproductive life, and the way she establishes gender relations. In Fig. 1 this individual perspective is represented on the left side by the duality of agency-freedom, which both constructs and is constructed by girls' capability for exercising sexual and reproductive rights.

Social institutions such as family, school, health, and welfare services highly influence girls' capability to exercise sexual and reproductive rights. The system of health protection to which girls are entitled might enhance girls' capability to exercise sexual and reproductive rights. Institutions are not gender neutral but display gender regimes, which are also strongly influenced by the gender order. The influence of structures upon individuals' agency-freedom is represented on the right side of Fig. 1.

This figure also tries to exemplify how the gender perspective (the triangle on top) and the rights perspective (the triangle on the bottom) could be combined to explore APs. There are gaps between the two approaches, but there are parallelisms as well: the interconnection between the individual sphere (right holder, freedom-agency) and the structural arena (duty-holders, gender regimes, and order) are the cornerstone in both approaches. The double-edged arrows attempt to express that not only structures influence individuals' capability to make decisions and exercise rights, but also individuals might have an influence on the way gender regimes operate and the system of sexual and reproductive health they are entitled to.

Research process

The previously described framework emerged deductively from four years of research and activism in the promotion of sexual and reproductive rights in the Amazon Basin of Ecuador (Orellana Province). Gender theory and the rights approach to health were applied to frame the results coming from four substudies that explored APs in this particular setting. I will first describe the research process and main results, to focus afterward on the discussion of them from a rights and gender perspective. The article ends with some reflections on how a rights and gender approach could contribute to research on APs.

Study area

The Province of Orellana is located in the Amazon region of Ecuador. It has a population of 103,032 inhabitants, of which 70% live in rural areas and 30.4% are indigenous. It is a young population with 26.8% adolescents aged 10–19 years (54). In rural areas people make their living from agriculture or work related to the oil industry. Socioeconomic and health indicators remain among the poorest in Ecuador (54, 55).

Since 2001, UNFPA Ecuador has been investing in the promotion of sexual and reproductive health in the area. Some achievements have been noticeable: sex education is ongoing in several schools, reproductive health has been integrated to some extent into existing public health services, and sexual and reproductive rights and gender equity have been promoted within grassroot organizations and incorporated into local policies and programs. Despite those achievements, women in Orellana still lack access to adequate reproductive health care: i.e. 34% pregnancies are labeled as unwanted (43.6% among indigenous women), skilled delivery attendance still remains low (47%), and APs are common – 37.4% of girls aged 15–19 are or have been pregnant, a doubling of the national prevalence (54, 56, 57).

Study aim and methodology

The study in Orellana aimed to explore APs from a rights and gender approach. It combined quantitative and qualitative methodologies in order to get different perspectives and, consequently, a more holistic picture. Quantitatively the study aimed toward describing the situation of women's reproductive health in Orellana, highlighting the gaps between policy and practice (Substudy I), and to find risk factors associated with APs (Substudy II). Qualitatively, the study aimed at exploring emotions and experiences regarding pregnancy and motherhood, from the adolescent girls' perspective (Substudy III), and to analyze stakeholders' discourses regarding APs and adolescents' sexual and reproductive health (Substudy IV).

The four substudies could be placed within the rights and gender framework described previously (Fig. 1). Substudy I focused on describing and analyzing the wider arena of women's sexual and reproductive health in Orellana. Substudy II concentrated on APs, exploring more narrowly associated factors. Substudy III focused on the experiences of the individual girl, particularly on her sexual agency-freedom. Substudy IV tackled the perspectives of the duty-bearers and institutional gender regimes, and its impact on girls' exercise of their sexual and reproductive rights.

Quantitative and qualitative methodologies were used in a situational approach (58). For Substudy I, a cross-sectional survey was first conducted in Orellana, and afterward collected information was analyzed using an instrument for policy analysis called Health and Rights of Women Assessment Instrument (HeRWAI) (59). Information from national policies and the ENDEMAIN – a demographic and maternal–child health national survey carried out every 4 years – was used, alongside the locally gathered data. The aim was to highlight the gaps between what should be happening – according to Ecuador's National Policy of SRHR – and what was really happening in Orellana (56, 60).

For the cross-sectional study 2025 women aged 10–44 answered a questionnaire that gathered information on: socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, delivery care, family planning, and APs (61). Information was disaggregated for place of residence (rural, urban) and ethnicity (indigenous, non-indigenous), in order to be able to document differences. Afterward, we conducted a policy analysis, using a modified version of HeRWAI that focused on three stages: (1) the description of Ecuador's National Policy of SRHR, (2) the actual situation of women's reproductive health in Orellana, and (3) the gaps between policy promises and the real situation of women's reproductive health in Orellana.

Substudy II consisted of a matched case-control study; 140 cases, any adolescent girl living in Orellana who was pregnant at the moment of the interview or who had been pregnant for the first time during the previous 2 years; and 262 matched controls, adolescent girls who had never been pregnant participated. Participants were identified in the community throughout the cross-sectional survey previously described. The questionnaire was based on the Nicaraguan ‘Investigación en Salud Reproductiva de adolescentes’ (61), and gathered sociodemographic details and information regarding family structure, education, and sexual and reproductive health. For assessing childhood trauma the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Questionnaire was used (62). After a preliminary bivariate analysis, the variables that showed significant association (p<0.05) were further analyzed using conditional logistic regression.

For Substudy III we conducted 11 in-depth interviews with adolescent girls who were pregnant or mothering. In the interviews, participants were encouraged to tell their story, and afterward, further explanations were asked for regarding experiences and emotions with pregnancy and motherhood, courtship, contraceptive use, and sexuality. Content analysis was used following Graneheim and Lundman's approach (63). After identifying and negotiating the categories (manifest content) and theme (latent content), we linked the findings with existing theory (58); in this study we focused on Connell's theory of gender and power (41, 43).

For Substudy IV we conducted 11 in-depth interviews and six focus group discussions with 41 service providers and policy makers of Orellana, exploring discourses on APs. The interview guide covered participants' experiences with APs, and their perceptions and opinions. During the analysis we looked for ‘interpretative repertoires,’ which can be described as clusters of meaning (64–66) that construct the discourse of APs in Orellana.

Several considerations were carried out to fulfill ethical standards. Approval for the study was sought from provincial authorities, and before entering each community the president was asked for permission. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study, and when minors where involved, permission was also sought from one of the parents living with them. Since the case-control study included questions related with violence, the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for research on violence against women were followed (67). Confidentiality and privacy were warranted.

Main results

Quantitative: reproductive health situation and risk factors for adolescent pregnancies (APs)

Ecuador's National Policy of SRHR, adopted in 2005, aimed to encourage and expand the exercise of sexual and reproductive rights. The policy established an action plan with nine different programs, from which this study focused on three: Maternal Mortality Reduction Program, Family Planning Program, and Adolescents' Program. While the policy statements were in accordance with international conventions such as the Conference for Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, and the International Conference of Cairo (1994), its actual implementation was weak in Orellana. Four gaps were identified. The first gap related to the incongruence between what the policy stated and its real implementation – i.e. while the policy stated that intercultural sensitivity was cornerstone, services were not including those issues and indigenous women were not reaching them. The second gap was between official data – coming from the ENDEMAIN – and locally gathered data. The former presented a less dismal situation; i.e. while according to ENDEMAIN unplanned pregnancies in the Amazon accounted for 43.3% of all pregnancies, local data for Orellana found that they were as high as 62.7%. The third and fourth gap related to geographical and cultural barriers: indigenous women living in rural areas were facing the lowest access to services; i.e. while skilled delivery care for urban women was 81%, for rural non-indigenous women care fell to 55%, and for rural indigenous women it dropped to 15% (57).

Regarding factors associated with APs, the conditional logistic regression analysis identified four factors: suffering sexual abuse during childhood and/or adolescence (OR 3.06, 95% CI 1.08–8.68), having initiated sexual intercourse before the age of 15 (OR 8.51, 95% CI 1.12–64.90), living in a very poor household (OR 15.23, 95% CI 1.43–162.45), and experiencing life periods of a year or longer without mother and father (OR 10.67, 95% CI2.67–42.63). For sexually initiated girls, non-use of contraceptives during their first sexual intercourse also increased the risk of AP (OR 4.30, 95% CI 1.33–13.90). Being married – or in a formal union – and not being enrolled in school were also associated with AP in the bivariate analysis. However, since the questionnaire did not ascertain whether those factors were present prior to the pregnancy, we could not conclude that they were true risk factors (68).

Qualitative: girls' experiences and emotions and providers discourses

In the content analysis seven categories emerged: fatalism, modest girls, and unreliable men, facing such an overwhelming responsibility alone, becoming a mother: the joy of having a baby but the end of childhood, misinformation and other barriers to pregnancy prevention, girl's mother as central pillar, and the importance of education; alongside the theme gendered structures constraining girls' agency.

In Orellana, the choices girls made regarding sexuality and reproduction were constrained by secrecy and taboos, lack of access to proper information, and gender structures that constructed girls as uninterested on those issues and subordinated to others' desires. Pregnancy and motherhood conveyed contradictory sentiments: while pregnancy raised emotions of sadness and anguish, motherhood was related with more optimistic emotions. At the same time motherhood marked the end of adolescence, and girls were faced with tremendous responsibilities with minimal support from partners or welfare programs. Despite those strong constraints, some mechanisms of resistance appeared: girls challenged external criticisms that marked them as failures, and girls clearly identified education as an opportunity for gaining economical autonomy and becoming independent from men.

There are girls who get married very young … like me … then let's say that when they are 20, they get divorced, then … what are you going to work on? If you are graduated from nothing, you don't have anything […] I have a friend who is now divorced, and I asked her if she has graduated from high-school and she told me that she just attended some courses to learn to sew … Now, sew!?, who is going to hire her? But if you graduate from high-school at least you can work as a secretary. (Alice, 16 years old)

During the analysis of the interviews with providers and policy makers, four interpretative repertoires emerged: sex is not for fun, gendered sexuality, and parenthood, professionalizing APs and idealization of traditional family.

Providers' discourses constructed girls' sexual and reproductive health from a moralistic approach. Information regarding contraceptives was provided theoretically, and not as something that young people should practice, and abstinence was emphasized as the best option for adolescents. Providers' approach to sexuality and parenthood was strongly gendered: on the one hand, girls were constructed as not interested in sex, and making responsible and selfless mothers; while, on the other hand, men were constructed as sexually driven and irresponsible fathers. AP has also become a health problem, and the medical profession has become responsible for dealing with it. This ‘medicalization’ has brought APs into the public health arena, but it has lead to paternalistic attitudes toward adolescents, and to the neglect of non-medical knowledge and young people's participation as well. The ‘idealization of traditional family’ repertoire emphasized the role of the nuclear heterosexual family as a cornerstone for adolescents' proper rising; at the same time the high prevalence of violence and exploitation against adolescents within the families was acknowledged.

Participants' accounts were not homogenous and consistent, since divergent and conflicting opinions were present: traditional-conservative opinions coexisted with emerging more progressive voices. This was especially felt in the educational system, where attitudes toward pregnant students have been changing recently.

But, colleague, you should have asked that question to the authorities at your school when they expelled that pregnant student: ‘And what would happen if that pregnant girl had been your daughter?’ … Just to see how will he look at it from that perspective … We do those things [expel a pregnant student], because they do not personally affect us … […] Then, that's the task that we who are working in the educational field have: we have to invite our colleagues to reconsider their positions … we have to be aware that those adolescents, those youngsters that are in process … they are part of us … and we have to stand for their rights. (Teacher, woman, FG teachers)

Discussion

Adolescent pregnancy (AP) from a rights and gender approach: a local perspective

Results from the study in Orellana did not support the conceptualization of AP as a way of challenging existing norms or a sign of increased girls' agency and freedom, such as some studies from other settings have evidenced (13, 69). APs, in this setting, reflected girls' constrained capability for exercising their sexual and reproductive rights. The fatalistic view of life and the secrecy and taboos surrounding sexuality, constructed a way of informing regarding sexuality that was based largely on falsehood and fear and did not enhance girls' agency. The encounter with providers did not contribute to enhancing girls' autonomy and agency, since it was characterized by poor confidentiality and paternalistic advices.

The present study also challenged individualistic approaches that emphasized girls' sole responsibility on pregnancy prevention, since it highlighted the role of structural factors – such as poverty, parental absence, or sexual violence – on AP. Even if delaying the first sexual intercourse and using contraceptives could be perceived as more under girls' control, gender structures that constrain girls' capability to negotiate safe sex, to be knowledgeable on sexuality and contraceptives, or to merely reject sexual proposals, may also play a key role on those decisions.

The findings concur with previous studies showing that in Latin America a high proportion of APs take place within formal-sanctioned unions, and that marriage might further complicate girls' capability to practice safe and consensual sex (5, 70). Even more, the association between marriage and school drop-out becomes a barrier for girls' economic autonomy and further entraps them.

In Orellana, the National Policy of SRHR that entitles all individuals to a network of sexual and reproductive health protection, remained scantly implemented. The HeRWAI analysis highlighted that inequities in reproductive health care access existed between Orellana and the rest of the country. It showed as well that inequities within Orellana were marked, and pointed out that the health system's greatest weakness was the failure to fulfill rural indigenous women needs.

In isolated areas such as Orellana, the implementation of sexual and reproductive health policies also faces the challenge of being inadequately represented by national statistics that may underrate the problem and ignore inequities. The lack of accountability mechanisms becomes another drawback for the implementation of well-intended policies.

The professionalization–medicalization of AP and adolescents' sexual and reproductive health had implications on the array of services that were conceptualized as public – sex education, health services – and the ones that remained as ‘private issues,’ responsibility of the girls and/or their families. The study in Orellana highlighted the importance of those ‘private issues’ – such as child care, services to deal with violence and sexual abuse, abortion services, or economic support – for ensuring an integral network of sexual and reproductive health protection.

Social determinants of sexual and reproductive health were also relevant in this study. Poverty and parental absence have also been associated with AP in other locations (15–17, 71). Gender subordination, exerted overtly through sexual violence or more subtly through symbolic constructions that idealize girls' passivity and obedience toward adult and men, further constrained girls' sexual and reproductive freedom. Another relevant social determinant of health was ageism, meaning unequal access to opportunities because of being young. Young girls had, on the one hand higher access to maternal services, while on the other hand they had lower access to contraceptive services. This ‘mother-nization’ of adolescents' services, already shown by other authors (21), may reinforce the ‘marianista’ unattainable ideal of womanhood that simultaneously combines sexual chastity and motherhood (49, 51, 72).

The present study highlighted a number of influential institutions where gender regimes were displayed. The institution of marriage was a powerful one. The fact that marriage was still positively conceptualized as a safe place for women poses a challenge for AP prevention programs in settings such as Orellana where many of those pregnancies took place within formal unions. The study also evidenced that marriage was actually not as safe for those girls as it was conceptualized: violence and unsafe sex within marriage seemed here as common as in other settings, and marriage was a strong reason for leaving school (70, 73, 74).

The ‘nuclear heterosexual family’ was another key institution. Families were perceived as the nucleus of society, and the place where adolescents should learn about sexuality and life. The presence of at least one parent was a protective factor, and girls' perceived their mothers as very important figures. At the same time, sexual abuse and violence within families were perceived as common, and the contradiction between the promotion of the ‘family model’ and the acknowledgment of many families as dangerous places was not raised.

The school was another important institution. Gender regimes were exhibited in the way schools approached pregnant and mothering students. Even if attitudes were becoming more progressive, still a schoolgirl's pregnancy was conceptualized as something shameful. Responsibility was placed on the girls, overlooking the father's role. In some schools patronizing attitudes were displayed, while in others, individual teachers dared to challenge the existing gender regimes. Since girls perceived education as an opportunity for gaining independence, it might be important to explore mechanisms to challenge schools' gender regimes in order to respond to girls' demands.

Health services also displayed gender regimes that shaped what kind of services were delivered, by whom, for whom, and in what way. The public–private dichotomy was reproduced in the division of what got included and what remained excluded. Gender regimes also affected the way services were delivered, in an adult-centered patriarchal fashion that reinforced girls' subordination toward adults, men, and professionals. It also diminished youth participation, since it was not perceived as relevant as adult-professionals' voices.

Even if institutional gender regimes mostly complied with the machismo–marianismo system, some mechanisms of resistance were found; for example, when individuals who hold some power (such as teachers, rectors, head of provincial departments) openly positioned themselves as advocates for adolescents' sexual and reproductive rights.

What does a rights and gender approach add to research on adolescent pregnancies (APs)? A global perspective

The study conducted in Orellana comprises several limitations. Apart from the limitations of each of the substudies, there were several issues that the study failed to investigate in depth: ethnicity, sexuality, and masculinity are among the main ones. Two important concepts, adolescence and normative heterosexuality, could have been looked at more thoroughly. Moreover, the generalizability of results coming from such a specific location could be arguable. However, a number of strengths can also be identified that could make a contribution to the field of APs and adolescents' sexual and reproductive health research.

One of the strengths relates to the use of a situational approach that relies on mixing perspectives for portraying a more holistic picture (58). Despite some researchers argument that qualitative and quantitative methodologies should not be mixed – since their theoretical bases are completely different – results from this study support the opposite position: the combination of methods can be a useful way to explore complex phenomena, such as health related issues (58, 75, 76). Sexual and reproductive health is an area where the interaction between the biological, psychological, social, and cultural becomes particularly relevant and, consequently, an approach that included diversity resulted fruitful. It has to be highlighted that mixing perspectives were not limited to combining quantitative and qualitative methodologies, but also included the incorporation of different voices. The inclusion of the perspectives of girls (as users, but also as mothers and as individuals), alongside the perspectives of stakeholders allowed us to explore the differences between life experiences and professional opinions. Mixing the internal and external perspectives was not a matter of choice, since while some of the researchers involved were familiar with the setting, others were not. However, it became an advantage because it helped on gaining access to participants and to facilitate dissemination of results (insiders' position), and it also helped to maintain the balance, triangulate results, and prevent becoming native (outsiders' position). Thus, the use of a situational approach that takes advantage of the mixture of different methodologies and perspectives could be valuable when exploring APs and adolescents sexual and reproductive health.

The application of a framework that combined a rights approach and a gender approach to explore APs and adolescents' sexual and reproductive health can also be considered useful. Differences between the two approaches do exist: i.e. the rights' approach is much more action oriented, while the gender approach has a much more developed theoretical background; the rights approach has frequently neglected gender inequities and had not considered – until recently – women's right to health as a basic human right; the strong role that the state plays as duty bearer in a rights approach overlooks other spaces where gender-based violence takes place, and might be conceptualizing too optimistically states as eager to warrant women's sexual and reproductive rights. Despite those gaps, this study also shows that combining rights and gender to research APs could be more fruitful than the still over-represented risk approach. The risk approach conceptualizes APs narrowly, as the consequence of ‘unsafe’ sexual practices carried out by individual girls, and lead to interventions that focus on ‘changing’ girls' sexual behavior, as if everything was under the individual girl's control. Many authors have already challenged this view (14, 15, 52, 77–79), and this study shows that a rights and gender approach could give a more integral and constructive picture.

From a rights and gender approach, adolescents' pregnancies are explored accounting for the interaction and tension between individual practices and actions and social structures. Sexual and reproductive practices of girls are dependent on the degree of freedom they enjoy in a particular setting and historical time. This freedom does not only depend on their own capability to make decisions, but also on the capability of the society where they live to empower them and surround them with an enabling environment that promotes their freedom. Blaming girls for getting pregnant too early, focusing interventions on changing the behavior of individual girls as if something were wrong with them, neglects the whole-complex picture and, thus, might not have a great impact. Disregarding power relations and structures that curtail girls' capability to exercise freedom on sexual and reproductive health issues may lead to interventions that wrongly assume the negotiation of sexual intercourse and condom use take place between individuals who enjoy equal positions, power, and privileges. A rights and gender approach adds complexity, but one that is needed in order to understand that AP is not merely the consequence of unsafe sexual intercourse but of complex interactions between pleasure, violence, affection, love, lust, power, and symbolism. It also helps to broaden the picture in order to include the duty-bearers role and responsibility on the issue of APs, not only at the level of providing services, but also at the level of alleviating inequities. In addition, it approaches health not merely as the provision of medical services but as integral wellbeing. This is a perspective that is extremely helpful for research on APs, where a large number of associated factors remain far beyond the scope of this sector.

Finally, since the rights and gender approach seems helpful for looking at complex issues, it could become valuable when researching other areas of sexual and reproductive health, such as sexually transmitted infections, HIV, maternal mortality, infertility, or sexual violence among others.

Conclusions

The application of the rights and gender framework to explore APs in Orellana allowed us to get a more holistic picture of the issue. From a global perspective, the combination of methodologies and approaches could be useful to explore sexual and reproductive health issues. The interaction between rights-holders and duty-bearers on the realization of sexual and reproductive rights, and the acknowledgment of the importance of gender–power relations on sexual and reproductive decision making could contribute to a better understanding of APs. Compared to the risk approach, a rights and gender approach could lead to more integral and constructive interventions, and it could also be valuable when exploring other sexual and reproductive health issues.

Acknowledgements

This research project was partly supported by the Umeå Centre for Global Health Research, funded by FAS, the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (Grant No. 2006-1512). The author is grateful to the valuable contribution of Marianne Wulff, Miguel San Sebastian, and Ann Ohman during the development of this project.

Conflict of interest and funding

The author has not received any funding or benefits from industry to conduct this study.

References

- 1.Organismo Regional Andino de Salud-Convenio Hipó lito Unanue. El embarazo en la adolescencia en la subregión Andina. [Adolescent pregnancy in the Andean Region]. Lima: ORASCONHU; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministerio Salud Pública Ecuador. Plan Andino de prevencio′n de embarazo en adolescentes. [Andean plan for adolescent pregnancy prevention]. Quito: MSP; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.García H, Avendaño-Becerra NP, Islas-Rodríguez MT. Neonatal and maternal morbidity among adolescent and adult women. A comparative study. Rev Investigación Clínica. 2008;60:94–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machado CJ. Impact of maternal age on birth outcomes: a population-based study of primiparous Brazilian women in the city of Sao Paulo. J Biosoc Sci. 2006;38:523–35. doi: 10.1017/S0021932005026660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzman JM, Hakkert R, Contreras JM, Falconier de Moyano M. Diagnóstico sobre salud sexual y reproductiva de adolescentes en América Latina y el Caribe. New York: UNFPA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayor S. Pregnancy and childbirth are leading causes of death in teenage girls in developing countries. BMJ. 2004;328:1152. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7449.1152-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNFPA. New York: UNFPA; 2007. Giving girls today and tomorrow: breaking the circle of adolescent pregnancy. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conde-Agudelo A, Belizan JM, Lammers C. Maternal-perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with adolescent pregnancy in Latin America: Cross-sectional study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:342–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clemmens D. Adolescent motherhood: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2003;28:93–99. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200303000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spear HJ, Lock S. Qualitative research on adolescent pregnancy: a descriptive review and analysis. J Pediatr Nurs. 2003;18:397–408. doi: 10.1016/s0882-5963(03)00160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de la Cuesta C. Taking love seriously: the context of adolescent pregnancy in Colombia. J Transcult Nurs. 2001;12:180–92. doi: 10.1177/104365960101200302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folle E, Geib LTC. Representações sociais das primíparas adolescentes sobre o cuidado materno ao recém-nascido. Rev Latino-Americana Enfermagem. 2004;12:183–90. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692004000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mccallum C, Reis APd. Childbirth as ritual in Brazil: young mothers experiences. Ethnos. 2005;70:335–60. [Google Scholar]

- 14.UNFPA EATA. Políticas públicas de juventud y derechos reproductivos: limitaciones, oportunidades y desafíos en América Latina y el Caribe. [Youth public policies and reproductive rights: limitations, opportunities and challenges in Latin America and the Caribbean]. New York: UNFPA; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Florez CE. Socioeconomic and contextual determinants of reproductive activity among adolescent women in Colombia. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2005;18:388–402. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892005001000002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flórez CE, Soto VE. El estado de la salud sexual y reproductiva en Ame′rica Latina y el Caribe: una visio′n global. [Sexual and reproductive health situation in Latin America and the Caribbean: a global perspective]. Washington, DC: BID; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guijarro S, Naranjo J, Padilla M, Gutierez R, Lammers C, Blum RW. Family risk factors associated with adolescent pregnancy: study of a group of adolescent girls and their families in Ecuador. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25:166–72. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chedraui P, Van Ardenne R, Wendte JF, Quintero JC, Hidalgo L. Knowledge and practice of family planning and HIV-prevention behaviour among just delivered adolescents in Ecuador: the problem of adolescent pregnancies. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;276:139–44. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0325-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chedraui PA, Hidalgo LA, Chavez MJ, San Miguel G. Determinant factors in Ecuador related to pregnancy among adolescents aged 15 or less. J Perinat Med. 2004;32:337–41. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2004.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hidalgo LA, Chedraui PA, Chavez MJ. Obstetrical and neonatal outcome in young adolescents of low socio-economic status: a case control study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2005;271:207–11. doi: 10.1007/s00404-004-0600-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varea MS. Maternidad adolescente: entre el deseo y la violencia. Quito, Ecuador: FLACSO Ecuador; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cabal L, Todd-Gher J. Reframing the right to health: legal advocacy to advance women′s reproductive rights. In: Clapham A, Robinson M, editors. Realizing the right to health. Zurich: Rüffer and Rub; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radicic I. Feminism and human rights: the inclusive approach to interpreting international human rights law. UCL Jurisprudence Rev. 2008;14:238–76. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giddens A. The constitution of society. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 25.London L. What is a human rights-based approach to health and does it matter? Health Hum Rights Int J. 2008;10:65–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riedle E. The human right to health: conceptual foundations. In: Clapham A, Robinson M, editors. Realizing the right to health. Zurich: Rüffer and Rub; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamin AE. Will we take suffering seriously? Reflections on what applying a human rights framework to health means and why we should care. Health Hum Rights Int J. 2008;10:45–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunt P, Bueno de Mesquita J. The rights to sexual and reproductive health. Essex: University of Essex; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hunt P. The human right to the highest attainable standard of health: new opportunities and challenges. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100:603–7. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glasier A, Gulmezoglu AM, Schmid GP, Moreno CG, Van Look PF. Sexual and reproductive health: a matter of life and death. Lancet. 2006;368:1595–607. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shalev C. Rights to sexual and reproductive health: the ICPD and the convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women. Health Hum Rights Int J. 2000;4:38–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sen G, Germain A, Chen L. Population policies reconsidered: health, empowerment, and rights. Boston, MA: Harvard School of Public Health; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petchesky R. Rights and needs: rethinking the connections in debates over reproductive and sexual rights. Health Hum Rights Int J. 2000;4:17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levison JH, Levison SP. Women's health and human rights. In: Agosín M, editor. Women, gender, and human rights—a global perspective. New Jersey: Rutgers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaw D. Sexual and reproductive health: rights and responsibilities. Lancet. 2006;368:1941–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69487-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gruskin S. Reproductive and sexual rights: do words matter? Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1737. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.147041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farmer P. Challenging orthodoxies: the road ahead for health and human rights. Health Hum Rights Int J. 2008;10:5–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braveman P, Gruskin S. Poverty, equity, human rights and health. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:539–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sundby J. Young people's sexual and reproductive health rights. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;20:355–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.UNHCHR; WHO. Geneva: UNHCHR–WHO; 2008. The right to health. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Connell RW. Gender. Cambridge: Polity Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fenstermaker S, West C. Doing gender, doing difference: inequality, power, and institutional change. New York: Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Connell RW. Gender and power. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bates LM, Hankivsky O, Springer KW. Gender and health inequities: a comment on the final report of the WHO commission on the social determinants of health. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:1002–4. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harding S. Is there a feminist method? In: Harding S, editor. Feminism and methodology. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 1987. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steenbeek G. Vrouwen op de Drempel. Gender en Moraliteit in een Mexicaanse Provinciestad. [Women on the threshold. Gender and morality in a Mexican town]. Amsterdam: Thela Publishers; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stobbe L. Doing machismo: legitimating speech acts as a selection discourse. Gender Work Organization. 2005;12:105–23. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torres JB, Solberg VS, Carlstrom AH. The myth of sameness among Latino men and their machismo. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72:163–81. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.72.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lagarde M. Los Cautiverios de las Mujeres: Madresposas, Monjas, Putas, Presas y Locas. [The captivity of women: motherwives, nuns, prostitutes, prisoners and crazy women]. México DF: Universidad Autónoma de México; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berglund S. Competing everyday discourses: the construction of heterosexual risk-taking behaviour among adolescents in Nicaragua. Malmo: Malmo Hogskola; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Montecino S. Madres y Huachos: Alegorías del Mestizaje Chileno. [Mothers and “huachos”: Allegories of Chilean “mestizaje”]. Santiago: Cuarto Propio CEDEM; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schutt-Aine J, Maddaleno M. Sexual health and development of adolescents and youth in the Americas: program and policy implications. Washington, DC: PAHO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krieger N. Embodiment: a conceptual glossary for epidemiology. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:350–5. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.024562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Honorable Consejo Provincial de Orellana. Sistema de información en demografía, salud y ambiente en la provincia de Orellana. Línea de base 2006. [Demographic, health and environmental surveillance system of Orellana province: Base line 2006]. Coca, Ecuador: Honorable Consejo Provincial de Orellana; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Instituto Nacional de Estadisticas y Censos Ecuador. VI Censo de poblacio′n y V de vivienda 2001. [VI Population Census and V Household Census 2001]. Quito, Ecuador: INEC; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 56.CEPAR. ENDEMAIN. 2004: Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud Materno Infantil, 2004. [National demographic and maternal health survey, 2004]. Quito, Ecuador: CEPAR. ENDEMAIN; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goicolea I, San Sebastián M, Wulff M. Women's reproductive rights in the Amazon basin of Ecuador: Challenges for transforming policy into practice. Health Hum Rights Int J. 2008;10:91–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dahlgren M, Emmelin M, Winkvist A. Qualitative methodology for international public health. Umeå: Umeå University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bakker S, Plagman H. Health rights of women assessment instrument. Utrecht: Aim for Human Rights; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ministerio Salud Pública Ecuador. Politica Nacional de Salud y Derechos Sexuales y Reproductivos. [National policy for sexual and reproductive rights and health]. Quito, Ecuador: MSP; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zelaya E. Adolescent pregnancies in Nicaragua: the importance of education Umeå (Sweden) Umeå: Umeå University; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adverse childhood experiences study. Atlanta, GA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Winther Jørgensen M, Phillips L. Discourse analysis as theory and methods. London: SAGE; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wetherell M, Potter J. Discourse analysis and the identification of interpretative repertoires. In: Antaki C, editor. Analysing everyday explanation. London: SAGE; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wheterell M, Potter J. Mapping the language of racism: Discourse and the legitimation of exploitation. Hertfordshire: Harvester Wheatsheaf; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 67.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2001. Putting women first: ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goicolea I, Wulff M, Ohman A, San Sebastian M. Risk factors for pregnancy among adolescent girls in Ecuador's Amazon basin: a case-control study. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2009;26:221–8. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892009000900006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dias ACG, Gomes WB. Conversas, em família, sobre sexualidade e gravidez na adolescência: percepção das jovens gestantes. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica. 2000;13:109–25. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clark S, Bruce J, Dude A. Protecting young women from HIV/AIDS: the case against child and adolescent marriage. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2006;32:79–88. doi: 10.1363/3207906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gigante DP, Barros FC, Veleda R, Goncalves H, Horta BL, Victora CG. [Maternity and paternity in the Pelotas birth cohort from 1982 to 2004–5, Southern Brazil] Rev Saude Publica. 2008;42:42–50. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102008000900007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Berglund S, Liljestrand J, Marín FdM, Salgado N, Zelaya E. The background of adolescent pregnancies in Nicaragua: a qualitative approach. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 73.World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund. Geneva: WHO–UNFPA; 2006. Married adolescents: no place of safety. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bunting A. Stages of development: marriage of girls and teens as an international human rights issue. Soc Leg Stud. 2005;14:17–38. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Barbour RS. Mixing qualitative methods: quality assurance or qualitative quagmire? Qual Health Res. 1998;8:352–61. doi: 10.1177/104973239800800306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Morgan DL. Practical strategies for combining qualitative and quantitative methods: applications to health research. Qual Health Res. 1998;8:362–76. doi: 10.1177/104973239800800307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Breheny M, Stephens C. Individual responsibility and social constraint: the construction of adolescent motherhood in social scientific research. Cult Health Sex. 2007;9:333–46. doi: 10.1080/13691050600975454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Heilborn ML, Brandao ER, Da Silva Cabral C. Teenage pregnancy and moral panic in Brazil. Cult Health Sex. 2007;9:403–14. doi: 10.1080/13691050701369441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, Crosby RA, Rosenthal SL. Prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections among adolescents: the importance of a socio-ecological perspective—a commentary. Public Health. 2005;119:825–36. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]