Abstract

(−)-Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) is the most abundant and biologically active polyphenol in green tea, and many of the therapeutic benefits of the beverage have been attributed to this compound. High concentrations of EGCG are cytotoxic and trigger genotoxic events in mammalian cells. Although this catechin affects a number of cellular systems, the genotoxic effects of several bioflavonoid-based dietary polyphenols are believed to be mediated, at least in part, by their actions on topoisomerase II. Therefore, the effects of green tea extract and EGCG on DNA cleavage mediated by human topoisomerase IIα and β were characterized. The extract and EGCG increased levels of DNA strand breaks generated by both enzyme isoforms. However, EGCG acted by a mechanism that was distinctly different from those of genistein, a dietary polyphenol, and etoposide, a widely prescribed anticancer drug. In contrast to these agents, EGCG exhibited all of the characteristics of a redox-dependent topoisomerase II poison that acts by covalently adducting to the enzyme. First, EGCG stimulated DNA scission mediated by both isoforms primarily at sites that were cleaved in the absence of compounds. Second, exposure of EGCG to the reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT) prior to its addition to DNA cleavage assays abrogated the effects of the catechin on DNA scission. Third, once EGCG stimulated topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage, exposure to DTT did not effect levels of DNA strand breaks. Finally, EGCG inhibited the DNA cleavage activities of topoisomerase IIα and β when incubated with either enzyme prior to the addition of DNA. Taken together, these results provide strong evidence that EGCG is a redox-dependent topoisomerase II poison, and utilizes a mechanism similar to that of 1,4-benzoquinone.

Introduction

Green tea, a rich source of polyphenols (i.e., bioflavonoids), is one of the most widely consumed beverages worldwide. Public interest in this popular beverage has grown as a result of the potential health promoting benefits that are attributed to its consumption (1–3). Green tea has been suggested to reduce the incidence of cardiovascular disease and cancers, such as breast, prostate, colorectal, and lung, in humans (3, 4).

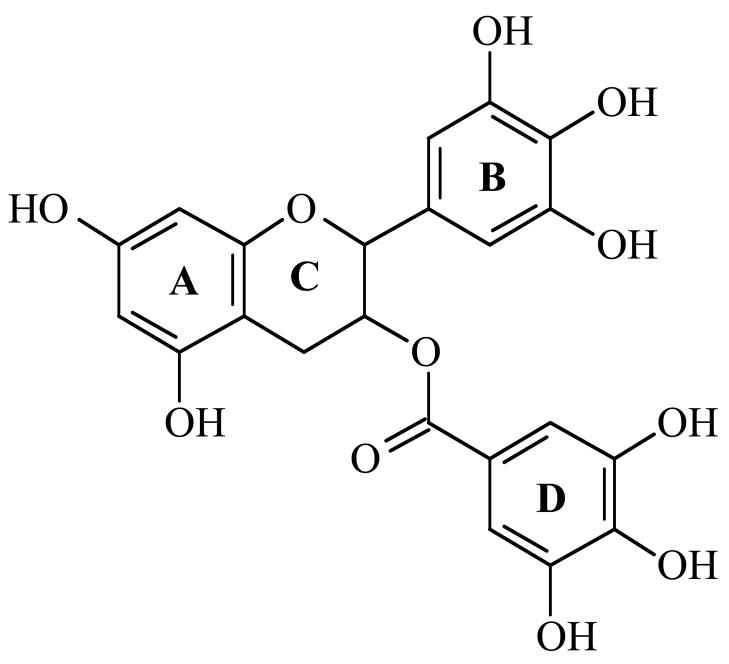

(−)-Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG)1 (Figure 1) is the most abundant and biologically active polyphenol in green tea, and many of the chemopreventative properties of the beverage have been attributed to this compound (1–4). EGCG affects a number of cellular systems, and high concentrations of this catechin are cytotoxic and trigger genotoxic events in cultured mammalian cells (5–9). In addition, EGCG inhibits proliferation, induces apoptosis, inhibits the activity of numerous protein kinases, and blocks the activation of transcription factors such as activator protein-1 and nuclear factor-κB (4, 10). EGCG also enhances DNA cleavage mediated by topoisomerase II (11).

Figure 1.

Structure of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate.

The mechanistic basis for the physiological actions of EGCG is not well defined. Because the compound undergoes redox chemistry, at least some of its cellular functions have been attributed to its antioxidant properties (1, 2, 4, 10). However, the genotoxic effects of several bioflavonoid-based dietary polyphenols are believed to be mediated, at least in part, by their actions on topoisomerase II (12–15).

Type II topoisomerases are ubiquitous enzymes that play essential roles in a number of fundamental DNA processes (16–21). Vertebrates encode two isoforms of the enzyme, topoisomerase IIα and β (16–24). These proteins display ~70% amino acid sequence identity and are enzymologically similar (20–27). However, they have distinct patterns of expression and physiological functions (17, 19–21, 24). Topoisomerase IIα is essential for the survival of actively growing tissues, and its expression rises dramatically during cell proliferation (28–30). This isoform is found at DNA replication forks and remains tightly associated with mitotic chromosomes (17, 31–33). As a result, topoisomerase IIα is thought to be the isoform that functions in growth-dependent processes, such as DNA replication and chromosome segregation (17, 19). In contrast, topoisomerase IIβ is dispensable at the cellular level (34, 35). Protein expression is independent of proliferative status, and the enzyme dissociates from chromosomes during mitosis (17, 24, 30, 36). Topoisomerase IIβ cannot compensate for the loss of the α isoform, and its physiological functions are not well defined (24, 32, 37).

Type II topoisomerases alter DNA topology by passing an intact helix through a double-stranded break that they generate in a separate segment of DNA (18, 20, 21, 38–40). To maintain genomic integrity during this process, topoisomerase II forms a covalent bond with the 5′-termini of the cleaved nucleic acid (41, 42, 43). This covalent enzyme-cleaved DNA intermediate is known as the cleavage complex. Despite the essential nature of topoisomerase II, conditions that increase the concentration of cleavage complexes ultimately generate permanent strand breaks in the genetic material that initiate mutagenic recombination/repair pathways (20, 21, 44–46). If these strand breaks overwhelm the cell, they induce death pathways (45).

Agents that increase topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage are called topoisomerase II poisons due to their ability to convert the enzyme to a cellular toxin that fragments the genome (20, 21, 47–50). Many of these compounds are widely prescribed as anticancer drugs and represent some of the most successful chemotherapeutic agents utilized to treat human malignancies (20, 21, 48, 51–54). However, topoisomerase II poisons also have been associated with the development of specific types of leukemia that involve rearrangements of the MLL gene at chromosomal band 11q23 (46, 55–58).

A previous report indicates that EGCG has the potential to poison calf thymus topoisomerase II (11). However, the enzyme preparation employed in this study contained a mixture of topoisomerase II isoforms. Recent studies suggest that the clinical effects of topoisomerase II poisons may be related to individual enzyme isoforms, with the chemotherapeutic properties being attributed primarily to topoisomerase IIα and the leukemogenic properties and off-target toxicity being attributed primarily to topoisomerase IIβ (59, 60). Since chemopreventative and genotoxic properties have both been ascribed to EGCG (1, 3–9), it is important to more fully understand the actions of the catechin on the individual isoforms of topoisomerase II. Therefore, the effects of green tea extract and EGCG on DNA cleavage and ligation mediated by human topoisomerase IIα and β were characterized. The extract and EGCG enhanced DNA cleavage mediated by both enzyme isoforms. In contrast to genistein, a dietary polyphenol, and etoposide, a widely prescribed anticancer drug, EGCG affected enzyme activity in a redox-dependent manner that appears to involve covalent adduction to topoisomerase IIα and β. Thus, EGCG utilizes a mechanism similar to 1,4-benzoquinone and other redox-dependent topoisomerase II poisons.

Experimental Procedures

Enzymes and Materials

Recombinant wild-type human topoisomerase IIα and β were expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and purified as described previously (61–63). Negatively supercoiled pBR322 DNA was prepared from Escherichia coli using a Plasmid Mega Kit (Qiagen) as described by the manufacturer. EGCG was purchased from LKT. 1,4-Benzoquinone and etoposide were obtained from Sigma. All compounds were prepared as 20 mM stock solutions in 100% DMSO and stored at −20 °C. Green tea extract was obtained as a retail product (product #44685) manufactured by Sundown, Inc. (Boca Raton, FL). The product was a combination of Camelia Sinensis leaf extract (150 mg per capsule) standardized to 50% total polyphenols and non-standardized C. Sinensis whole leaf (250 mg per capsule). The specific concentration of EGCG in the product was not indicated. Green tea extract was prepared as a 20 mg/mL stock solution in 100% DMSO and stored at −20 °C.

Cleavage of Plasmid DNA

DNA cleavage reactions were performed using the procedure of Fortune and Osheroff (64). Assay mixtures contained 220 nM topoisomerase IIα or β, 5 nM negatively supercoiled pBR322 DNA, 0–100 μg/mL green tea extract or 0–500 μM EGCG in 20 μL of DNA cleavage buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 2.5% (v/v) glycerol]. DNA cleavage mixtures were incubated for 6 min at 37 °C. In some cases, 0–10 min time courses for DNA cleavage were monitored. Enzyme-DNA cleavage intermediates were trapped by adding 2 μL of 5% SDS and 1 μL of 375 mM EDTA, pH 8.0. Proteinase K was added (2 μL of a 0.8 mg/mL solution), and reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 45 °C to digest topoisomerase II. Samples were mixed with 2 μL of 60% sucrose in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 0.5% bromophenol blue, and 0.5% xylene cyanol FF, heated for 2 min at 45 °C, and subjected to electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels in 40 mM Tris-acetate, pH 8.3, and 2 mM EDTA containing 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide. DNA cleavage was monitored by the conversion of negatively supercoiled plasmid DNA to linear molecules. DNA bands were visualized by ultraviolet light and quantified using an Alpha Innotech digital imaging system.

In assays that determined the reversibility of topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage induced by EGCG, EDTA (final concentration of 18 mM) was added to reaction mixtures prior to treatment with SDS. To determine whether cleaved DNA was protein-linked, proteinase K treatment was omitted. To examine the effects of a reducing agent on the actions of EGCG against human topoisomerase IIα or β, 500 μM dithiothreitol (DTT) was incubated with 500 μM EGCG, 25 μM 1,4-benzoquinone, 50 μM genistein, or 50 μM etoposide for 5 min prior to initiating DNA cleavage reactions. Alternatively, DTT was added to reaction mixtures for 5 min following a 6 min DNA cleavage reaction.

To examine the effects of EGCG on human topoisomerase IIα or β in the absence of DNA, 500 μM EGCG, 25 μM 1,4-benzoquinone, 50 μM genistein, or 50 μM etoposide was incubated with 220 nM enzyme for 0–10 min at 37 °C in 15 μL of DNA cleavage buffer. Cleavage was initiated by adding 5 nM negatively supercoiled pBR322 DNA (in 5 μL of cleavage buffer) to the reaction mixture.

Finally, to determine whether EGCG undergoes a molecular alteration that enhances its reactivity toward human topoisomerase IIα or β, 500 μM EGCG was incubated alone in DNA cleavage buffer for 3 min at 37 °C prior to the initiation of reactions.

Ligation of Cleaved Plasmid DNA by Human Topoisomerase II

DNA ligation mediated by human topoisomerase IIα or β was monitored according to the procedure of Byl et al. (65). DNA cleavage/ligation equilibria were established for 6 min at 37 °C as described above in the absence of compound or in the presence of 500 μM EGCG or 50 μM genistein. Ligation was initiated by shifting samples from 37 to 0 °C. Reactions were stopped at time points up to 15 s by the addition of 2 μL of 5% SDS followed by 1 μL of 375 mM EDTA, pH 8.0. Samples were processed and analyzed as above. Ligation was monitored by the loss of linear DNA.

DNA Cleavage Site Utilization

DNA cleavage sites were mapped using a modification (66) of the procedure of O’Reilly and Kreuzer (67). A linear 4330 bp fragment (HindIII/EcoRI) of pBR322 plasmid DNA singly labeled with 32P on the 5′-terminus of the HindIII site was used as the cleavage substrate. The pBR322 DNA substrate was linearized by treatment with HindIII. Terminal 5′-phosphates were removed by treatment with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase and replaced with [32P]phosphate using T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP. The DNA was cut with EcoRI, and the 4330 bp singly end labeled fragment was purified from the small EcoRI-HindIII fragment by passage through a CHROMA SPIN+TE-100 column (Clontech). DNA cleavage reaction mixtures contained 0.7 nM labeled pBR322 DNA and 90 nM human topoisomerase II in 50 μL of DNA cleavage buffer. Assays were performed in the absence of compound or in the presence of 12.5 μM etoposide, 50 μM genistein, 50 μM 1,4-benzoquinone, or 0–500 μM EGCG. Reactions were incubated for 6 min (topoisomerase IIα) or 0.5 min (topoisomerase IIβ) at 37 °C. Cleavage intermediates were trapped by adding 5 μL of 5% SDS followed by 4 μL of 250 mM EDTA, pH 8.0. Topoisomerase II was digested with proteinase K (5 μL of a 0.8 mg/mL solution) for 30 min at 45 °C. DNA products were precipitated twice in 100% ethanol, washed in 70% ethanol, dried, and resuspended in 6 μL of 40% formamide, 10 mM NaOH, 0.02% xylene cyanol FF, and 0.02% bromophenol blue. Samples were subjected to electrophoresis in a denaturing 6% polyacrylamide sequencing gel in 100 mM Tris-borate, pH 8.3, and 2 mM EDTA. The gel was fixed in a 10% methanol/10% acetic acid mixture for 2 min and dried. DNA cleavage products were analyzed on a Bio-Rad Molecular Imager FX.

Results

Enhancement of Topoisomerase II-mediated DNA Cleavage by Green Tea Extract

Green tea is a rich source of biologically active polyphenols that are believed to impact a number of important physiological processes (4, 10). Since several classes of polyphenols, including flavones, flavonols, isoflavones, and catechins have been reported to affect the activity of mammalian type II topoisomerases (11, 12, 68), the effects of green tea extract on the DNA cleavage activity of human topoisomerase IIα and β were assessed.

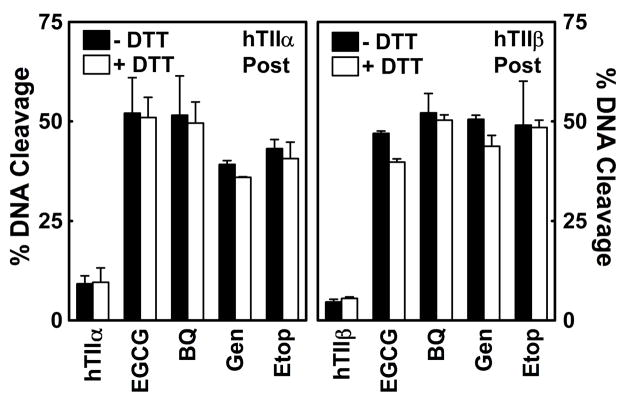

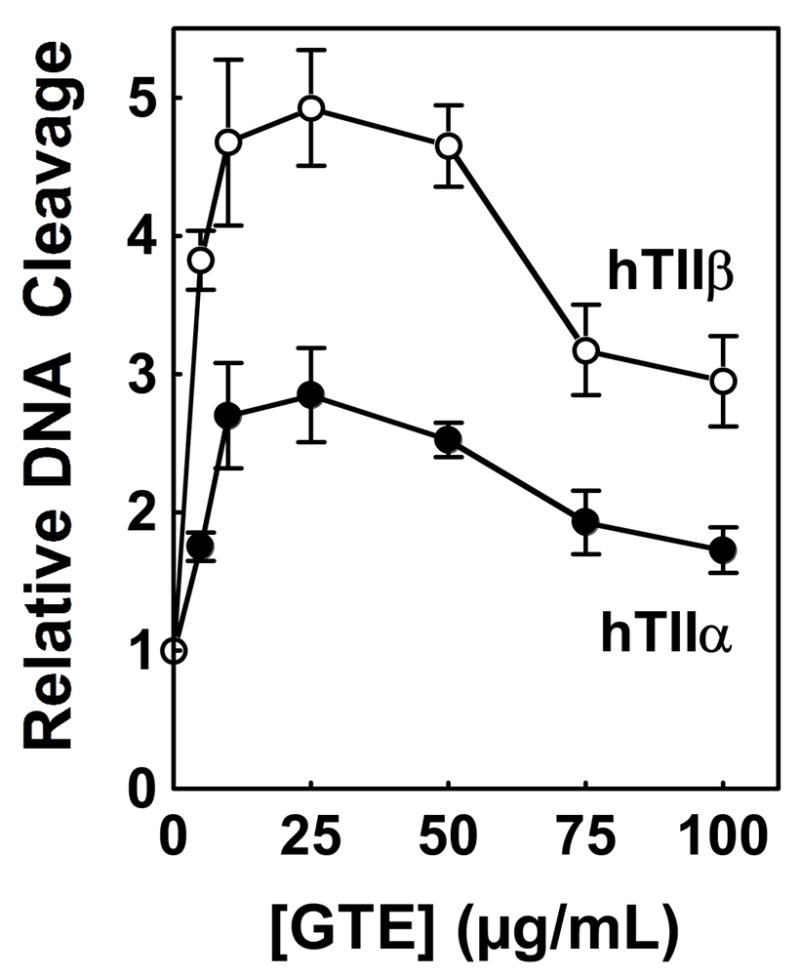

Green tea extract increased levels of DNA cleavage mediated by both enzyme isoforms (Figure 2). Scission rose ~3-fold for topoisomerase IIα and ~5-fold for topoisomerase IIβ. In both cases, optimal cleavage enhancement was observed at ~25 μg/mL green tea extract, with cleavage decreasing at higher concentrations. The basis for the decline in activity of the extract above 25 μg/mL is not known. One possibility is that compounds in the extract intercalate into the plasmid substrate and inhibit the enzymes by diminishing topoisomerase II-DNA binding or by altering the apparent supercoiled state of the double helix. However, no DNA intercalation was observed at concentrations of extract up to 200 μg/mL (data not shown). As a second possibility, green tea leaves contain tannins, and some of these compounds have been shown to inhibit the activity of type II topoisomerases (69, 70).

Figure 2.

Effects of green tea extract on double-stranded DNA cleavage mediated by human topoisomerase IIα and β. Data for DNA cleavage mediated by topoisomerase IIα (hTIIα; closed circles) and topoisomerase IIβ (hTIIβ; open circles) in the presence of 0–100 μg/mL green tea extract (GTE) are shown. Levels of cleavage were compared to those in the absence of compounds (set to 1.0). Error bars represent standard deviations for three independent experiments.

Enhancement of Topoisomerase II-mediated DNA Cleavage by EGCG

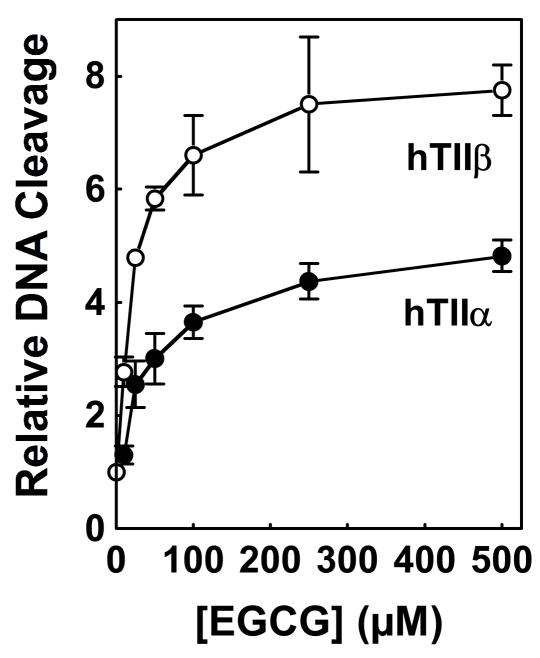

EGCG, the major polyphenol in green tea, represents ~40–60% of the bioflavonoids in green tea extract (6, 71). Since ~25 μM/mL green tea extract contains ~20–30 μM EGCG, the effects of the isolated catechin on the DNA cleavage activities of topoisomerase IIα and β were determined (Figure 3). EGCG increased levels of scission with both isoforms (~5- and 8-fold, respectively) over a wide range of concentrations. It is notable that the concentration of EGCG in plasma and salivary samples is estimated to be as high as 4 and 48 μM, respectively, following consumption of ~3 cups of green tea (5, 72). As seen in Figure 3, significant topoisomerase II-DNA cleavage enhancement was observed in this range.

Figure 3.

Effects of EGCG on double-stranded DNA cleavage mediated by human topoisomerase IIα and β. Data for DNA cleavage mediated by topoisomerase IIα (hTIIα; closed circles) and topoisomerase IIβ (hTIIβ; open circles) in the presence of 0–500 μM EGCG are shown. Levels of cleavage were compared to those in the absence of compounds (set to 1.0). Error bars represent standard deviations for three independent experiments.

No decline in cleavage enhancement was observed at concentrations as high as 500 μM EGCG. This indicates that the decrease in activity seen at high concentrations of green tea extract was not due to an effect of EGCG.

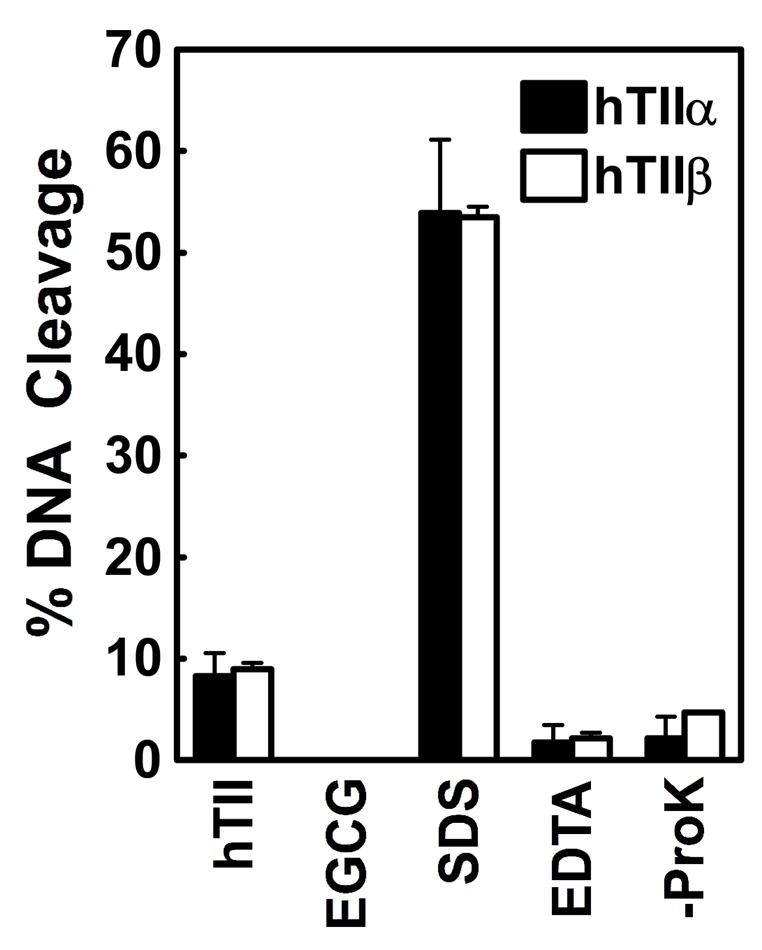

A series of control reactions was performed to ensure that the DNA cleavage enhancement observed with EGCG was topoisomerase II-mediated (Figure 4). No EGCG-induced DNA scission was seen in the absence of enzyme. Furthermore, with both topoisomerase IIα and β, EGCG-induced cleavage was reversed when reactions were incubated with EDTA prior to trapping cleavage complexes with SDS. This reversibility is inconsistent with an enzyme-independent reaction. Finally, cleaved plasmid was covalently linked to topoisomerase II. In the absence of proteinase K, the linear DNA band disappeared and was replaced by a band that remained at the origin of the gel or by a diffuse smear with reduced electrophoretic mobility (data not shown).

Figure 4.

EGCG-induced DNA cleavage is mediated by topoisomerase II. Data for human topoisomerase IIα (hTIIα; closed bars) and topoisomerase IIβ (hTIIβ; open bars) are shown. Control reactions contained DNA and enzyme in the absence of EGCG (hTII), DNA and 500 μM EGCG in the absence of enzyme (EGCG), or complete reaction mixtures treated with SDS prior to adding EDTA (SDS). The reversibility of DNA cleavage induced by 500 μM EGCG was determined by incubating reactions with EDTA prior to trapping cleavage complexes with SDS (EDTA). To determine whether DNA cleavage induced by EGCG was protein-linked, proteinase K treatment was omitted (-ProK). Error bars represent standard deviations for three independent experiments.

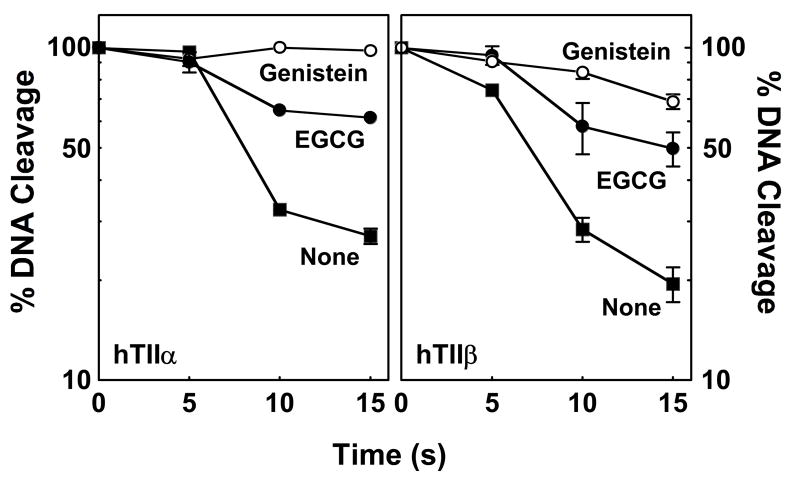

The DNA cleavage and ligation reactions of topoisomerase II exist in a tightly coupled equilibrium (18, 20, 21, 38–40). Some topoisomerase II poisons, such as etoposide or genistein, increase levels of cleavage complexes by inhibiting the DNA ligation activity of the enzyme (68, 73). In contrast, abasic sites and other lesions that act as topoisomerase II poisons have little effect on ligation and act primarily by stimulating the forward rate of scission (74–78). Finally, some bioflavonoid-based topoisomerase II poisons have a modest effect on ligation and presumably affect both the cleavage and ligation reactions (68). EGCG appears to fall into this last category (Figure 5). The effects of the catechin on DNA ligation mediated by topoisomerase IIα or β were intermediate to those of no drug reactions and those that contain genistein.

Figure 5.

Effects of EGCG on topoisomerase II-mediated DNA ligation. Data for human topoisomerase IIα (hTIIα; left panel) and topoisomerase IIβ (hTIIβ; right panel) are shown. DNA ligation was examined in the absence of compounds (None; closed squares) or in the presence of 500 μM EGCG (closed circles) or 50 μM genistein (open circles). Samples were incubated at 37 °C to establish DNA cleavage/ligation equilibria and were shifted to 0 °C to initiate the ligation reaction. Equilibrium levels of DNA cleavage were set to 100% at time zero. Ligation was quantified by the loss of linear molecules. Errors bars represent standard deviations for three independent experiments.

EGCG is a Redox-dependent Topoisomerase II Poison

With the exception of DNA lesions, topoisomerase II poisons can be categorized into two broad classes. Members of the first group act by a redox-independent mechanism. These compounds interact with topoisomerase II at the protein-DNA interface (in the vicinity of the active site tyrosine) in a non-covalent manner (20, 21, 48–50). Redox-independent topoisomerase II poisons include several anticancer drugs (e.g., etoposide) and dietary bioflavonoids (e.g., genistein), and display a number of characteristic properties. They generally alter the DNA cleavage specificity (site utilization) of the enzyme due to their interactions with the double helix in the tertiary enzyme-DNA-drug complex (79). Furthermore, because their actions against topoisomerase II do not depend on redox chemistry, they are unaffected by the presence of reducing agents (80). Finally, these compounds induce similar levels of enzyme-mediated DNA scission whether they are added to the binary topoisomerase II-DNA complex or are incubated with the enzyme prior to the addition of the double helix (80).

Topoisomerase II poisons in the second class act in a redox-dependent fashion (21, 80–87) and form covalent adducts with the enzyme at amino acid residues distal to the active site (84). The best-characterized members of this group are quinones, such as 1,4-benzoquinone and polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) metabolites (80–86). In contrast to redox-independent topoisomerase II poisons, this latter class generally enhances DNA cleavage at sites normally cut by the enzyme (80, 84). Moreover, because of the dependence on redox chemistry, their ability to form covalent adducts with topoisomerase II (and hence their ability to enhance topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage) is blocked by the presence of reducing agents (80, 84, 88, 89). Finally, while redox-dependent poisons enhance topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage when added to the enzyme-DNA complex, these compounds display the distinguishing feature of inhibiting topoisomerase II function when incubated with the protein prior to the addition of DNA (80, 84, 88, 89).

A previous study demonstrated that the bioflavonoid genistein (which contains a single hydroxyl group on its B-ring) poisons topoisomerase IIα and β in a redox-independent manner (68). EGCG contains a similar three-ring bioflavonoid core, but undergoes a complex set of redox-dependent reactions, presumably due to the three hydroxyl groups on its B-ring (see Figure 1) (4, 90–94). Therefore, it is not obvious whether EGCG acts in a manner that requires redox chemistry.

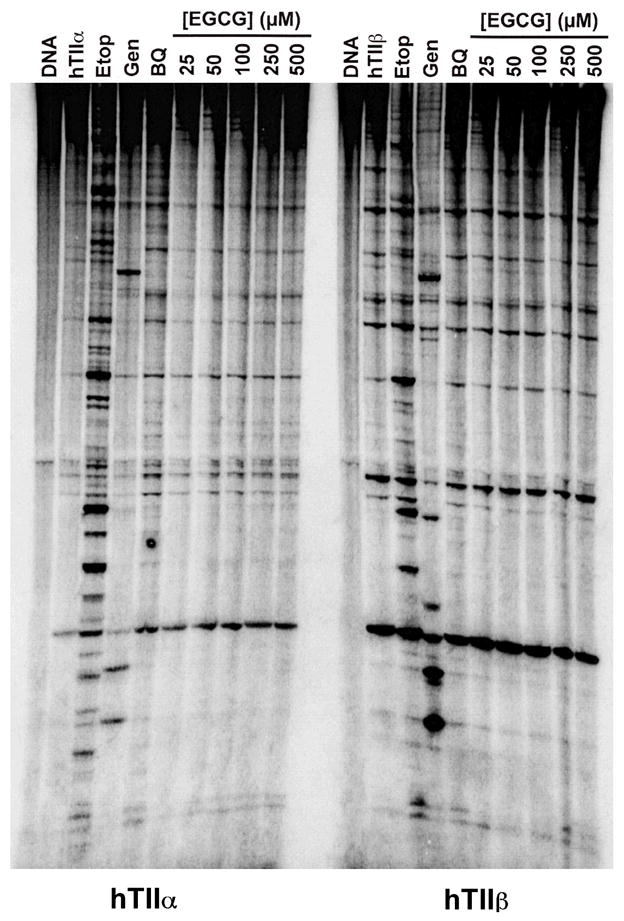

As a first step in elucidating the basis for the actions of EGCG as a topoisomerase II poison, the effects of the compound on the DNA cleavage site specificity of human topoisomerase IIα and β were assessed. As seen in Figure 6, EGCG stimulated DNA scission mediated by both isoforms primarily at sites that were cleaved by the enzymes in the absence of compounds. A similar result was seen with 1,4-benzoquinone. In contrast, etoposide and genistein enhanced cleavage at a number of sites that were not intrinsic to either topoisomerase II isoform. These findings suggest that EGCG may be a redox-dependent topoisomerase II poison.

Figure 6.

Effects of EGCG on DNA cleavage site utilization by topoisomerase II. Data for human topoisomerase IIα (hTIIα; left) and topoisomerase IIβ (hTIIβ; right) are shown. Autoradiograms of polyacrylamide gels are shown. DNA cleavage reactions contained enzyme in the absence of compounds (hTIIα or hTIIβ), or in the presence of 12.5 μM etoposide (Etop), 50 μM genistein (Gen), 25 μM 1,4-benzoquinone (BQ), or 25–500 μM EGCG. A DNA control is shown in the far left lane of each autoradiogram (DNA). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

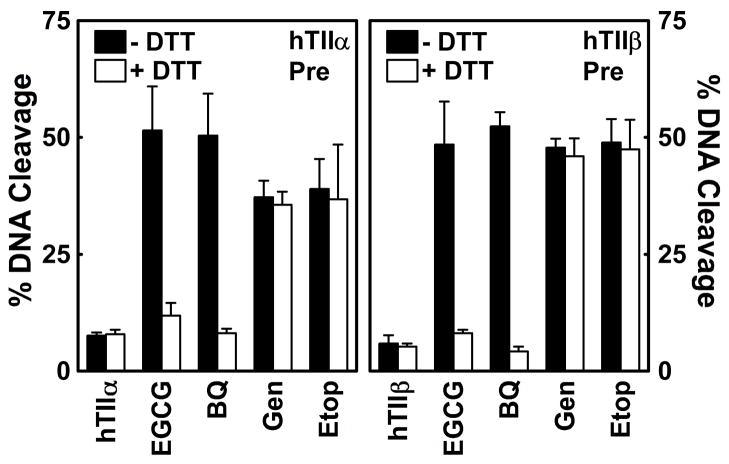

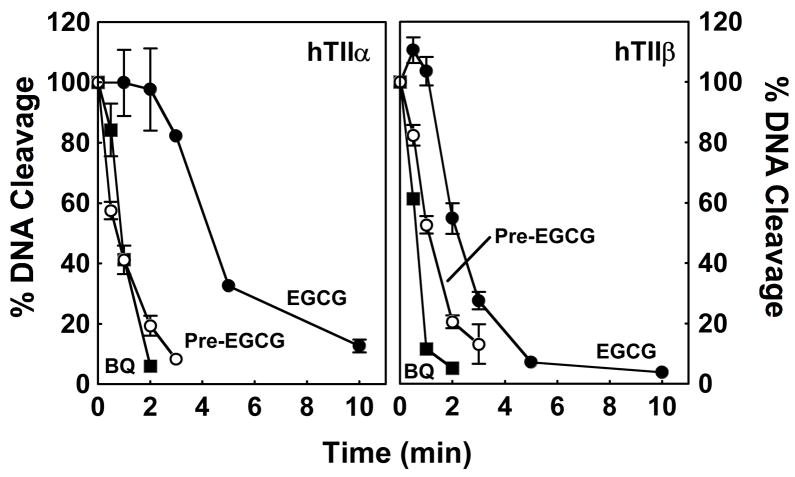

To test this hypothesis, the effects of the reducing agent, DTT, on the activity of EGCG were determined (Figure 7). Prior to the addition of the catechin or other agents to the topoisomerase II (α or β)-DNA complex, compounds were incubated with 500 μM DTT for 5 min. While this treatment had no significant effect on the enzyme alone or on the actions of the redox-independent poisons, genistein and etoposide, it markedly decreased the ability of EGCG to enhance DNA cleavage. Levels of scission dropped ~90% as compared to reactions in the absence of DTT. A similar result was observed for 1,4-benzoquinone. This finding provides strong evidence that EGCG is a redox-dependent topoisomerase II poison.

Figure 7.

Effects of DTT on the ability of EGCG to enhance DNA cleavage mediated by topoisomerase II. Data for human topoisomerase IIα (hTIIα; left panel) and topoisomerase IIβ (hTIIβ; right panel) are shown. EGCG (500 μM) was incubated without DTT (−DTT; closed bars) or with 500 μM DTT (+DTT; open bars) prior to its addition to topoisomerase II-DNA complexes. Control reactions contained DNA and enzyme in the absence of compounds (hTIIα or hTIIβ), or in the presence of 25 μM 1,4-benzoquinone (BQ), 50 μM genistein (Gen), or 50 μM etoposide (Etop). Error bars represent standard deviations for three independent experiments.

A common feature of redox-dependent topoisomerase II poisons is that they form covalent adducts with the enzyme (80–86). Since the maintenance of this covalent interaction is independent of the redox state of the poison, DTT has no effect on DNA cleavage after adducts are formed. Similar to results seen with 1,4-benzoquinone, once cleavage complexes were formed in the presence of EGCG, DTT did not diminish the efficacy of the catechin (Figure 8). Together with the data shown in Figure 7, this finding suggests that EGCG acts by forming covalent adducts with topoisomerase IIα and β.

Figure 8.

Effects of DTT on EGCG activity toward topoisomerase II after DNA cleavage complexes are established. Data for human topoisomerase IIα (hTIIα; left panel) and topoisomerase IIβ (hTIIβ; right panel) are shown. Following DNA cleavage enhancement in the presence of 500 μM EGCG, topoisomerase II-DNA cleavage complexes were further incubated without DTT (−DTT; closed bars) or with 500 μM DTT (+DTT; open bars). Control reactions contained DNA and enzyme in the absence of compounds (hTIIα or hTIIβ), or cleavage complexes established in the presence of 25 μM 1,4-benzoquinone (BQ), 50 μM genistein (Gen), or 50 μM etoposide (Etop). Error bars represent standard deviations for three independent experiments.

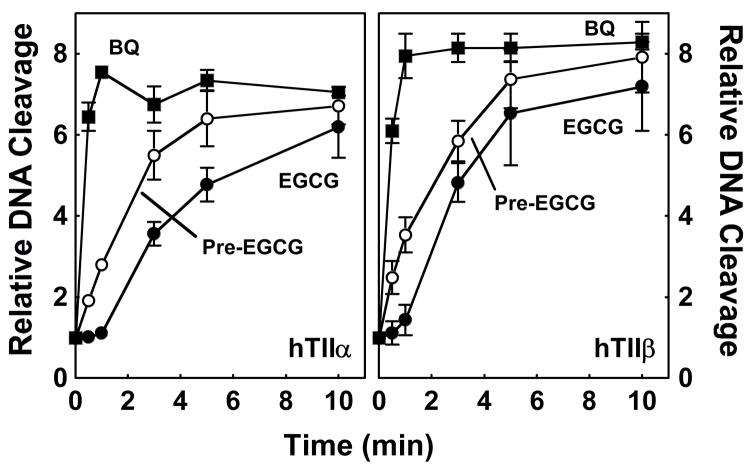

A final distinguishing feature of redox-dependent topoisomerase II poisons is the fact that they inactivate enzyme function when they are incubated with the protein prior to the addition of DNA (80, 82, 84, 88, 89, 95). To determine whether this was the case for EGCG, the catechin was added to reaction mixtures that contained topoisomerase IIα or β for times up to 10 min before the addition of plasmid. Levels of cleavage were compared to those observed when EGCG was added to a mixture that contained the enzyme-DNA complex (set to 100%). As seen for other redox-dependent topoisomerase II poisons, when topoisomerase IIα or β was incubated with EGCG before the addition of DNA, there was a time-dependent decrease in cleavage activity (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Time-dependence of EGCG-induced inhibition of topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage when incubated with the enzyme prior to the addition of DNA. Data for human topoisomerase IIα (hTIIα; left panel) and topoisomerase IIβ (hTIIβ; right panel) are shown. Enzymes were treated with the following compounds for 0–10 min prior to the addition of DNA: 500 μM EGCG (closed circles), 25 μM 1,4-benzoquinone (BQ; closed squares), or 500 μM EGCG that was incubated in cleavage buffer for 3 min before its addition to reactions (Pre-EGCG; open circles). Levels of cleavage were compared to those when compounds were added to the enzyme-DNA complex (set to 100%). Error bars represent standard deviations for three independent experiments.

It is notable that the t1/2 of inactivation was considerably longer for the catechin than for 1,4-benzoquinone. Moreover, there was a lag of ~2 and ~1 min, respectively, before EGCG-induced inactivation of topoisomerase IIα or β was observed. However, when the catechin was incubated alone in reaction buffer for 3 min prior to its addition to the enzyme, its reactivity rose considerably. T1/2 values for inactivation were comparable to those seen for 1,4-benzoquine, and the previously observed delay disappeared. These results suggest that EGCG undergoes redox chemistry that enhances its reactivity toward topoisomerase IIα and β. However, the nature of the redox-induced change(s) is unknown at the present time.

To determine whether the redox-dependent changes in EGCG also enhance its actions as a topoisomerase II poison, the ability of the catechin to stimulate DNA cleavage mediated by topoisomerase IIα and β was examined over time (Figure 10). The time course for stimulation of DNA scission (when EGCG was added to the enzyme-DNA complex) was similar to that for inactivation of the enzyme isoforms. EGCG was less reactive than 1,4-benzoquinone, and a lag was observed prior to cleavage enhancement. Once again, reactivity increased, and the lag disappeared when EGCG was incubated in reaction buffer prior to its addition to the enzyme-DNA complex. Therefore, it is likely that redox chemistry induces a change in EGCG that makes it a more potent topoisomerase II poison.

Figure 10.

Time-dependence of EGCG-induced stimulation of topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage when incubated with the enzyme-DNA complex. Data for human topoisomerase IIα (hTIIα; left panel) and topoisomerase IIβ (hTIIβ; right panel) are shown. Enzymes were treated with 500 μM EGCG (closed circles), 25 μM 1,4-benzoquinone (BQ; closed squares), or 500 μM EGCG that was incubated in cleavage buffer for 3 min before its addition to reactions (Pre-EGCG; open circles), and a 10-min time course for DNA cleavage was examined. Levels of cleavage were compared to those in the absence of compounds (set to 1.0). Error bars represent standard deviations for three independent experiments.

Discussion

EGCG is the most abundant polyphenol in green tea and is believed to be responsible for many of the beneficial effects of this popular beverage on human health, including chemoprevention (1–4). High concentrations of the catechin trigger genotoxic events in mammalian cells (5–9). Despite the potential therapeutic benefits of polyphenols in adults, the consumption of bioflavonoid-rich diets during pregnancy increases the risk of infant leukemias with MLL rearrangements ~3-fold (14). Type II topoisomerases are believed to initiate the chromosomal rearrangements in these leukemias, (12, 14, 15, 54, 96–98) and a number of polyphenols have been found to enhance DNA cleavage mediated by these enzymes (11, 68). Therefore, the effects of EGCG on the DNA cleavage activities of human topoisomerase IIα and β were assessed.

Results indicate that EGCG is a strong topoisomerase II poison against both isoforms. In contrast to genistein, a bioflavonoid that acts in a redox-independent, non-covalent manner (68), EGCG is a redox-dependent topoisomerase II poison that appears to act by covalently adducting the enzyme. Thus, the mechanistic basis for the actions of EGCG against topoisomerase II is similar to those of quinone-based compounds, such as 1,4-benzoquinone (80–86).

Green tea extract increases levels of DNA cleavage mediated by human topoisomerase IIα and β, and the concentration of EGCG (~20–30 μM) at maximal extract activity is consistent with this catechin being an important (if not the most important) topoisomerase II-active compound in green tea. However, comparing the cleavage titrations of green tea extract and EGCG, it is clear that other topoisomerase II-active compounds (either stimulatory or inhibitory) are present in the extract. Although the specific nature of these compounds has not been elucidated, myricetin, quercetin, kaempferol, and other bioflavonoids that are topoisomerase II poisons are present in green tea (3, 99).

When EGCG is added to initiate reactions, there is a 1–2 min delay before alterations in topoisomerase II activity are observed. This time delay disappears when the compound is incubated in reaction buffer for 3 min prior to its addition to topoisomerase II or the enzyme-DNA complex. EGCG is known to undergo a complex set of redox-dependent chemical changes that have been ascribed primarily to its B-ring (4, 10, 90–94). Thus, it is likely that an oxidized derivative of EGCG is more reactive toward topoisomerase II than the parent catechin. On the basis of previous studies with redox-dependent topoisomerase II poisons (80–86), it is predicted that this reactive species contains a quinone on the B-ring. However, given the complexity of the redox chemistry of EGCG, other structural rearrangements cannot be eliminated.

In summary, EGCG stimulates DNA cleavage mediated by human topoisomerase IIα and β. Given the high concentration of this catechin in green tea, its potency against the type II enzymes, and its plasma concentration range after consumption of the beverage, it is possible that topoisomerase II mediates some of the physiological actions of EGCG.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jo Ann Byl, Joseph Deweese, and Amanda Gentry for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviation: EGCG, (−)-epigallocatechin gallate.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health research grant GM33944. OJB was a trainee under grant 5 T32 CA09582 from the National Institutes of Health and was supported in part by Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Predoctoral Fellowship F31 GM78744 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Isbrucker RA, Bausch J, Edwards JA, Wolz E. Safety studies on epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) preparations. Part 1: genotoxicity. Food and Chem Toxicol. 2006;44:626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isbrucker RA, Edwards JA, Wolz E, Davidovich A, Bausch J. Safety studies on epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) preparations. Part 2: Dermal, acute and short-term toxicity studies. Food and Chem Toxicol. 2006;44:636–650. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang CS, Lambert JD, Ju J, Lu G, Sang S. Tea and cancer prevention: molecular mechanisms and human relevance. Tox Appl Pharmacol. 2007;224:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sang S, Hou Z, Lambert JD, Yang CS. Redox properties of tea polyphenols and related biological activities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:1704–1714. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertram B, Bollow U, Rajaee-Behbahani N, Burkle A, Schmezer P. Induction of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and DNA damage in human peripheral lymphocytes after treatment with (−)-epigallocatechin-gallate. Mutat Res. 2003;534:77–84. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(02)00245-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weisburg JH, Weissman DB, Sedaghat T, Babich H. In vitro cytotoxicity of epigallocatechin gallate and tea extracts to cancerous and normal cells from the human oral cavity. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;95:191–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2004.pto_950407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanadzu M, Lu Y, Morimoto K. Dual function of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) in healthy human lymphocytes. Cancer Lett. 2006;241:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noda C, He J, Takano T, Tanaka C, Kondo T, Tohyama K, Yamamura H, Tohyama Y. Induction of apoptosis by epigallocatechin-3-gallate in human lymphoblastoid B cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362:951–957. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lambert JD, Sang S, Yang CS. Possible controversy over dietary polyphenols: benefits vs risks. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:583–585. doi: 10.1021/tx7000515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong J, Lu H, Meng X, Ryu JH, Hara Y, Yang CS. Stability, cellular uptake, biotransformation, and efflux of tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate in HT-29 human colon adenocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7241–7246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austin CA, Patel S, Ono K, Nakane H, Fisher LM. Site-specific DNA cleavage by mammalian DNA topoisomerase II induced by novel flavone and catechin derivatives. Biochem J. 1992;282:883–889. doi: 10.1042/bj2820883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strick R, Strissel PL, Borgers S, Smith SL, Rowley JD. Dietary bioflavonoids induce cleavage in the MLL gene and may contribute to infant leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:4790–4795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070061297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynch A, Harvey J, Aylott M, Nicholas E, Burman M, Siddiqui A, Walker S, Rees R. Investigations into the concept of a threshold for topoisomerase inhibitor-induced clastogenicity. Mutagenesis. 2003;18:345–353. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geg003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spector LG, Xie Y, Robison LL, Heerema NA, Hilden JM, Lange B, Felix CA, Davies SM, Slavin J, Potter JD, Blair CK, Reaman GH, Ross JA. Maternal diet and infant leukemia: the DNA topoisomerase II inhibitor hypothesis: a report from the children’s oncology group. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:651–655. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Waalwijk van Doorn-Khosrovani SB, Janssen J, Maas LM, Godschalk RW, Nijhuis JG, van Schooten FJ. Dietary flavonoids induce MLL translocations in primary human CD34+ cells. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1703–1709. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang JC. DNA Topoisomerases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:635–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nitiss JL. Investigating the biological functions of DNA topoisomerases in eukaryotic cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1400:63–81. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Champoux JJ. DNA topisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:369–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang JC. Cellular roles of DNA topoisomerases: a molecular perspective. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:430–440. doi: 10.1038/nrm831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilstermann AM, Osheroff N. Stabilization of eukaryotic topoisomerase II- DNA cleavage complexes. Curr Top Med Chem. 2003;3:321–338. doi: 10.2174/1568026033452519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClendon AK, Osheroff N. DNA topoisomerase II, genotoxicity, and cancer. Mutat Res. 2007;623:83–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drake FH, Zimmerman JP, McCabe FL, Bartus HF, Per SR, Sullivan DM, Ross WE, Mattern MR, Johnson RK, Crooke ST. Purification of topoisomerase II from amsacrine-resistant P388 leukemia cells. Evidence for two forms of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:16739–16747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drake FH, Hofmann GA, Bartus HF, Mattern MR, Crooke ST, Mirabelli CK. Biochemical and pharmacological properties of p170 and p180 forms of topoisomerase II. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8154–8160. doi: 10.1021/bi00446a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Austin CA, Marsh KL. Eukaryotic DNA topoisomerase IIβ. Bioessays. 1998;20:215–226. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199803)20:3<215::AID-BIES5>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai-Pflugfelder M, Liu LF, Liu AA, Tewey KM, Whang-Peng J, Knutsen T, Huebner K, Croce CM, Wang JC. Cloning and sequencing of cDNA encoding human DNA topoisomerase II and localization of the gene to chromosome region 17q21–22. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:7177–7181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.19.7177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Austin CA, Fisher LM. Isolation and characterization of a human cDNA clone encoding a novel DNA topoisomerase II homologue from HeLa cells. Febs Letters. 1990;266:115–117. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81520-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan KB, Dorman TE, Falls KM, Chung TD, Mirabelli CK, Crooke ST, Mao J. Topoisomerase IIα and topoisomerase IIβ genes: characterization and mapping to human chromosomes 17 and 3, respectively. Cancer Res. 1992;52:231–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heck MM, Earnshaw WC. Topoisomerase II: A specific marker for cell proliferation. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:2569–2581. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.6.2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsiang YH, Wu HY, Liu LF. Proliferation-dependent regulation of DNA topoisomerase II in cultured human cells. Cancer Res. 1988;48:3230–3235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Woessner RD, Mattern MR, Mirabelli CK, Johnson RK, Drake FH. Proliferation- and cell cycle-dependent differences in expression of the 170 kilodalton and 180 kilodalton forms of topoisomerase II in NIH-3T3 cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1991;2:209–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bauman ME, Holden JA, Brown KA, Harker WG, Perkins SL. Differential immunohistochemical staining for DNA topoisomerase IIα and β in human tissues and for DNA topoisomerase IIβ in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Mod Pathol. 1997;10:168–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grue P, Grasser A, Sehested M, Jensen PB, Uhse A, Straub T, Ness W, Boege F. Essential mitotic functions of DNA topoisomerase IIα are not adopted by topoisomerase IIβ in human H69 cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33660–33666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christensen MO, Larsen MK, Barthelmes HU, Hock R, Andersen CL, Kjeldsen E, Knudsen BR, Westergaard O, Boege F, Mielke C. Dynamics of human DNA topoisomerases IIα and IIβ in living cells. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:31–44. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen M, Beck WT. DNA topoisomerase II expression, stability, and phosphorylation in two VM-26-resistant human leukemic CEM sublines. Oncol Res. 1995;7:103–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang X, Li W, Prescott ED, Burden SJ, Wang JC. DNA topoisomerase IIβ and neural development. Science. 2000;287:131–134. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5450.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Isaacs RJ, Davies SL, Sandri MI, Redwood C, Wells NJ, Hickson ID. Physiological regulation of eukaryotic topoisomerase II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1400:121–137. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dereuddre S, Delaporte C, Jacquemin-Sablon A. Role of topoisomerase IIβ in the resistance of 9-OH-ellipticine-resistant Chinese hamster fibroblasts to topoisomerase II inhibitors. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4301–4308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berger JM. Type II Topoisomerases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:26–32. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang JC. Moving one DNA double helix through another by a type II DNA topoismerase: the story of a simple molecular machine. Quart Rev Biophys. 1998;31:107–144. doi: 10.1017/s0033583598003424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corbett KD, Berger JM. Structure, molecular mechanisms, and evolutionary relationships in DNA topoisomerases. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2004;33:95–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.33.110502.140357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sander M, Hsieh T. Double strand DNA cleavage by type II DNA topoisomerase from Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:8421–8428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu LF, Rowe TC, Yang L, Tewey KM, Chen GL. Cleavage of DNA by mammalian DNA topoisomerase II. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:15365–15370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zechiedrich EL, Christiansen K, Andersen AH, Westergaard O, Osheroff N. Double-stranded DNA cleavage/religation reaction of eukaryotic topoisomerase II: evidence for a nicked DNA intermediate. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6229–6236. doi: 10.1021/bi00441a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baguley BC, Ferguson LR. Mutagenic properties of topoisomerase-targeted drugs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1400:213–222. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaufmann SH. Cell death induced by topoisomerase-targeted drugs: more questions than answers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1400:195–211. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00136-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Felix CA. Secondary leukemias induced by topoisomerase-targeted drugs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1400:233–255. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kreuzer KN, Cozzarelli NR. Escherichia coli mutants thermosensitive for deoxyribonucleic acid gyrase subunit A: effects on deoxyribonucleic acid replication, transcription, and bacteriophage growth. J Bacteriol. 1979;140:424–435. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.2.424-435.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li TK, Liu LF. Tumor cell death induced by topoisomerase-targeting drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:53–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walker JV, Nitiss JL. DNA topoisomerase II as a target for cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Invest. 2002;20:570–589. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120002156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pommier Y, Marchand C. Interfacial inhibitors of protein-nucleic acid interactions. Curr Med Chem Anti-Canc Agents. 2005;5:421–429. doi: 10.2174/1568011054222337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hande KR. Clinical applications of anticancer drugs targeted to topoisomerase II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1400:173–184. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hande KR. Etoposide: four decades of development of a topoisomerase II inhibitor. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1514–1521. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baldwin EL, Osheroff N. Etoposide, topoisomerase II and cancer. Curr Med Chem Anticancer Agents. 2005;5:363–372. doi: 10.2174/1568011054222364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Felix CA, Kolaris CP, Osheroff N. Topoisomerase II and the etiology of chromosomal translocations. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:1093–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rowley JD. 1993 Robert R. deVilliers Lecture. Chromosome translocations: dangerous liaisons. Leukemia. 1994;8:S1–S6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith MA, Rubinstein L, Anderson JR, Arthur D, Catalano PJ, Freidlin B, Heyn R, Khayat A, Krailo M, Land VJ, Miser J, Shuster J, Vena D. Secondary leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome after treatment with epipodophyllotoxins. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:569–577. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.2.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Felix CA. Leukemias related to treatment with DNA topoisomerase II inhibitors. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;36:525–535. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Andersen MK, Christiansen DH, Jensen BA, Ernst P, Hauge G, Pedersen-Bjergaard J. Therapy-related acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with MLL rearrangements following DNA topoisomerase II inhibitors, an increasing problem: report on two new cases and review of the literature since 1992. Br J Haematol. 2001;114:539–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lyu YL, Kerrigan JE, Lin CP, Azarova AM, Tsai YC, Ban Y, Liu LF. Topoisomerase IIβ mediated DNA double-strand breaks: implications in doxorubicin cardiotoxicity and prevention by dexrazoxane. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8839–8846. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Azarova AM, Lyu YL, Lin CP, Tsai YC, Lau JY, Wang JC, Liu LF. Roles of DNA topoisomerase II isozymes in chemotherapy and secondary malignancies. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:11014–11019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704002104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Worland ST, Wang JC. Inducible overexpression, purification, and active site mapping of DNA topoisomerase II from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4412–4416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elsea SH, Hsiung Y, Nitiss JL, Osheroff N. A yeast type II topoisomerase selected for resistance to quinolones. Mutation of histidine 1012 to tyrosine confers resistance to nonintercalative drugs but hypersensitivity to ellipticine. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1913–1920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kingma PS, Greider CA, Osheroff N. Spontaneous DNA lesions poison human topoisomerase IIα and stimulate cleavage proximal to leukemic 11q23 chromosomal breakpoints. Biochemistry. 1997;36:5934–5939. doi: 10.1021/bi970507v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fortune JM, Osheroff N. Merbarone inhibits the catalytic activity of human topoisomerase IIα by blocking DNA cleavage. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17643–17650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Byl JA, Fortune JM, Burden DA, Nitiss JL, Utsugi T, Yamada Y, Osheroff N. DNA topoisomerases as targets for the anticancer drug TAS-103: primary cellular target and DNA cleavage enhancement. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15573–15579. doi: 10.1021/bi991791o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baldwin EL, Byl JA, Osheroff N. Cobalt enhances DNA cleavage mediated by human topoisomerase IIα in vitro and in cultured cells. Biochemistry. 2004;43:728–735. doi: 10.1021/bi035472f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O’Reilly EK, Kreuzer KN. A unique type II topoisomerase mutant that is hypersensitive to a broad range of cleavage-inducing antitumor agents. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7989–7997. doi: 10.1021/bi025897m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bandele OJ, Osheroff N. Bioflavonoids as poisons of human topoisomerase IIα and IIβ. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6097–6108. doi: 10.1021/bi7000664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kashiwada Y, Nonaka G, Nishioka I, Lee KJ, Bori I, Fukushima Y, Bastow KF, Lee KH. Tannins as potent inhibitors of DNA topoisomerase II in vitro. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 1993;82:487–492. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600820511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wall M, Wani M, Brown D, Fullas F, Oswald J, Josephson F, Thornton N, Pezzuto J, Beecher C, Farnsworth N, Cordell G, Kinhorn AD. Effect of tannins on screening of plant extracts for enzyme inhibitory activity and techniques for their removal. Phytomedicine. 1996;3:281–285. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(96)80067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gradisar H, Pristovsek P, Plaper A, Jerala R. Green tea catechins inhibit bacterial DNA gyrase by interaction with its ATP binding site. J Med Chem. 2007;50:264–271. doi: 10.1021/jm060817o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang CS, Chung JY, Yang G, Chhabra SK, Lee MJ. Tea and tea polyphenols in cancer prevention. J Nutr. 2000;130:472S–478S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.472S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Osheroff N. Effect of antineoplastic agents on the DNA cleavage/religation reaction of eukaryotic topoisomerase II: inhibition of DNA religation by etoposide. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6157–6160. doi: 10.1021/bi00441a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kingma PS, Corbett AH, Burcham PC, Marnett LJ, Osheroff N. Abasic sites stimulate double-stranded DNA cleavage mediated by topoisomerase II: anticancer drugs mimic endogenous DNA lesions. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:21441–21444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kingma PS, Osheroff N. Spontaneous DNA damage stimulates topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7488–7493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cline SD, Jones WR, Stone MP, Osheroff N. DNA abasic lesions in a different light: solution structure of an endogenous topoisomerase II poison. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15500–15507. doi: 10.1021/bi991750s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sabourin M, Osheroff N. Sensitivity of human type II topoisomerases to DNA damage: stimulation of enzyme-mediated DNA cleavage by abasic, oxidized and alkylated lesions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1947–1954. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.9.1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Velez-Cruz R, Riggins JN, Daniels JS, Cai H, Guengerich FP, Marnett LJ, Osheroff N. Exocyclic DNA lesions stimulate DNA cleavage mediated by human topoisomerase IIα in vitro and in cultured cells. Biochemistry. 2005;44:3972–3981. doi: 10.1021/bi0478289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Capranico G, Guano F, Moro S, Zagotto G, Sissi C, Gatto B, Zunino F, Menta E, Palumbo M. Mapping drug interactions at the covalent topoisomerase II-DNA complex by bisantrene/amsacrine congeners. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12732–12739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lindsey RH, Jr, Bromberg KD, Felix CA, Osheroff N. 1,4-Benzoquinone is a topoisomerase II poison. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7563–7574. doi: 10.1021/bi049756r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang H, Mao Y, Chen AY, Zhou N, LaVoie EJ, Liu LF. Stimulation of topoisomerase II-mediated DNA damage via a mechanism involving protein thiolation. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3316–3323. doi: 10.1021/bi002786j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lindsey RH, Bender RP, Osheroff N. Stimulation of topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage by benzene metabolites. Chem Biol Interact. 2005:153–154. 197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bender RP, Lindsey RH, Jr, Burden DA, Osheroff N. N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine, the toxic metabolite of acetaminophen, is a topoisomerase II poison. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3731–3739. doi: 10.1021/bi036107r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bender RP, Lehmler HJ, Robertson LW, Ludewig G, Osheroff N. Polychlorinated Biphenyl Quinone Metabolites Poison Human Topoisomerase IIα: Altering Enzyme Function by Blocking the N-Terminal Protein Gate. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10140–10152. doi: 10.1021/bi0524666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bender RP, Osheroff N. Mutation of cysteine residue 455 to alanine in human topoisomerase IIα confers hypersensitivity to quinones: enhancing DNA scission by closing the N-terminal protein gate. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:975–981. doi: 10.1021/tx700062t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bender RP, Ham AJ, Osheroff N. Quinone-induced enhancement of DNA cleavage by human topoisomerase IIα: adduction of cysteine residues 392 and 405. Biochemistry. 2007;46:2856–2864. doi: 10.1021/bi062017l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bender RP, Osheroff N. DNA Topoisomerases as Targets for the Chemotherapeutic Treatment of Cancer. In: Dai W, editor. Cancer Drug Discovery and Development Checkpoint Responses in Cancer Therapy. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2007. pp. 59–92. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Frantz CE, Chen H, Eastmond DA. Inhibition of human topoisomerase II in vitro by bioactive benzene metabolites. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104(Suppl 6):1319–1323. doi: 10.1289/ehp.961041319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Baker RK, Kurz EU, Pyatt DW, Irons RD, Kroll DJ. Benzene metabolites antagonize etoposide-stabilized cleavable complexes of DNA topoisomerase IIα. Blood. 2001;98:830–833. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Valcic S, Muders A, Jacobsen NE, Liebler DC, Timmermann BN. Antioxidant chemistry of green tea catechins. Identification of products of the reaction of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate with peroxyl radicals. Chem Res Toxicol. 1999;12:382–386. doi: 10.1021/tx990003t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Valcic S, Burr JA, Timmermann BN, Liebler DC. Antioxidant chemistry of green tea catechins. New oxidation products of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate and (−)-epigallocatechin from their reactions with peroxyl radicals. Chem Res Toxicol. 2000;13:801–810. doi: 10.1021/tx000080k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Langley-Evans SC. Antioxidant potential of green and black tea determined using the ferric reducing power (FRAP) assay. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2000;51:181–188. doi: 10.1080/09637480050029683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lambert JD, Yang CS. Mechanisms of cancer prevention by tea constituents. J Nutr. 2003;133:3262S–3267S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.10.3262S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sang S, Lambert JD, Hong J, Tian S, Lee MJ, Stark RE, Ho CT, Yang CS. Synthesis and structure identification of thiol conjugates of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate and their urinary levels in mice. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:1762–1769. doi: 10.1021/tx050151l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen H, Eastmond DA. Topoisomerase inhibition by phenolic metabolites: a potential mechanism for benzene’s clastogenic effects. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:2301–2307. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.10.2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ross JA, Potter JD, Robison LL. Infant leukemia, topoisomerase II inhibitors, and the MLL gene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1678–1680. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.22.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ross JA, Potter JD, Reaman GH, Pendergrass TW, Robison LL. Maternal exposure to potential inhibitors of DNA topoisomerase II and infant leukemia (United States): a report from the Children’s Cancer Group. Cancer Causes Control. 1996;7:581–590. doi: 10.1007/BF00051700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ross JA. Maternal diet and infant leukemia: a role for DNA topoisomerase II inhibitors? Int J Cancer Suppl. 1998;11:26–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Huafu W, Helliwell K. Determination of flavonols in green and black tea leaves and green tea infusions by high-performance liquid chromatography. Food Res Int. 2001:2–3. [Google Scholar]