Abstract

Background

This study used standardized assessments to evaluate the association between childhood maltreatment (i.e., emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, and emotional and physical neglect) and Axis I and II psychiatric disorders in patients presenting for bariatric surgery.

Methods

Participants (N = 230) provided demographic information and completed the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, short form. The Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV was used to assess Axis I clinical disorders and Axis II personality disorders.

Results

Approximately 66% of participants had a history of childhood maltreatment. Individuals reporting childhood maltreatment had a greater number of lifetime Axis I diagnoses than did those without, although the effect for physical neglect was no longer significant after controlling for multiple comparisons. With respect to specific Axis I diagnoses, a history of emotional or sexual abuse was associated with increased rates of lifetime mood and anxiety disorder diagnoses. Emotional neglect also was associated with increased rates of mood disorder diagnoses, and physical abuse was associated with increased rates of substance use disorders. There was no significant association between childhood maltreatment and personality psychopathology.

Conclusion

This study confirms high rates of childhood maltreatment in patients presenting for bariatric surgery that are associated with increased prevalence of lifetime mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders. Future prospective studies should include evaluation of a broad range of mental health and childhood experiences in order to tease apart the nature of the relationships between these factors and their potential impact on post-surgical outcomes.

Keywords: Obesity, gastric bypass, child abuse, mental disorders, psychopathology

A growing body of research indicates that childhood maltreatment (i.e., physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, and neglect) is associated with increased body weight and risk of obesity during adolescence and adulthood.1-4 With notable exceptions,5,6 this work has suggested that rates of childhood maltreatment are especially high among individuals with extreme obesity (i.e., body mass index [BMI] ≥ 40 kg/m2) relative to those with more moderate obesity. For example, the Adverse Childhood Experiences study, which included 13,177 members of a California health maintenance organization, found that a history of childhood physical, sexual, or emotional abuse was more strongly related to risk of adult BMI ≥ 40 than to risk of adult BMI ≥ 30.3 Similarly, Felitti7 reported significantly higher rates of “morbid obesity” (i.e., > 100 lbs. overweight) among individuals with a history of childhood sexual abuse relative to control subjects; there was no significant difference between the sexually abused group and controls with respect to rates of more moderate obesity (i.e., 50-100 lbs. overweight).

Childhood maltreatment may be particularly common among obese patients presenting for bariatric surgery. A recent study comparing extremely obese women (BMI ≥ 40) presenting for bariatric surgery to women with class I-II obesity (BMI = 30.0-39.9) enrolled in a behavioral weight loss program found significantly higher rates of childhood physical and sexual abuse in the bariatric surgery candidates relative to the behavioral weight control group.8 Similarly, research using standardized assessments to document a full range childhood maltreatment has reported elevated rates of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, as well as physical and emotional neglect, in bariatric surgery candidates compared to normative community samples.9,10

Less is known about the clinical significance of childhood maltreatment in bariatric surgery candidates. Although some research has indicated that a history of childhood abuse is associated with increased rates of psychopathology and psychiatric treatment seeking,11-13 other studies have found few differences between bariatric surgery candidates with and without reported histories of childhood maltreatment on measures of psychological functioning.9,10 These inconsistencies may be due in part to methodological limitations of the extant literature including non-standardized assessments of childhood maltreatment11-13 and the use of self-report questionnaires to document current and lifetime psychiatric symptomatology.9,10,12,13

There are compelling reasons to evaluate the relation between childhood maltreatment and psychiatric morbidity in bariatric surgery candidates. Community studies have consistently documented an association between childhood maltreatment and numerous forms of psychopathology, including mood, anxiety, eating, substance use, and personality disorders.14-18 Research also has suggested that current and lifetime psychiatric disorders are prevalent in patients presenting for bariatric surgery and are associated with indicators of clinical severity in this group. For example, our research group recently administered standardized assessments to evaluate a full range of psychopathology in 288 individuals presenting for bariatric surgery.19 Sixty-six percent of participants reported a lifetime history of at least one Axis I clinical disorder, and 28.5% met criteria for an Axis II personality disorder at the time of evaluation. Axis I disorders include, but are not limited to, major mental disorders such as mood, anxiety, eating, and substance use disorders. Axis II personality disorders refer to enduring, inflexible and pervasive patterns of impairment in social interactions. Both Axis I and II disorders were related to decreased functional health status in bariatric surgery candidates; Axis I psychopathology also was associated with increased pre-surgery BMI in our sample.19

No study to date has used standardized assessments to evaluate the relation between childhood maltreatment and psychiatric morbidity in bariatric surgery candidates. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to document the association between different forms of maltreatment and Axis I and II psychopathology in a large sample of patients presenting for their first bariatric surgery. We sought to address the limitations of previous research by using a well-validated self-report questionnaire to evaluate childhood maltreatment and standardized diagnostic interviews to document Axis I clinical disorders and Axis II personality psychopathology.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This study was conducted as part of a larger prospective investigation of behavioral and psychosocial factors in relation to outcome following gastric bypass. Recruitment procedures have been described in detail elsewhere.19 After a complete description of the study, participants signed written informed consent forms approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board.

Of 300 eligible patients who participated in the baseline evaluation, 230 (76.7%) completed assessments of childhood maltreatment (Note: The childhood maltreatment measure was not administered to the first 67 patients enrolled in the study; an additional 3 patients failed to complete the measure). Participants were primarily female (n = 191; 83.0%) and Caucasian (n = 210; 91.3%). More than half of the sample was married (n = 129; 56.1%), and 70% (n = 161) had at least some post-high school training or education. Mean age was 44.8 (± 9.6) years, and mean BMI was 51.4 (± 9.8) kg/m2. As reported previously,19 rates of psychiatric morbidity were high in the sample. Specifically, 65.2% of participants in the current study (n = 150) had at least one lifetime Axis I clinical disorder, and 31.7% (n = 73) met criteria for an Axis II personality disorder.

Procedure

Patients completed a battery of self-report questionnaires and interviews prior to undergoing gastric bypass. Assessments were conducted independently of the surgery approval process to enhance patients' willingness to disclose problems they perceived might lead to the denial of surgery. To further maximize study participation, questionnaires were returned by mail, and interviews were conducted in person or by telephone. The literature on diagnostic interviewing clearly indicates that telephone interviews are equivalent to in-person interviews in terms of validity, reliability, precision of estimates, and response rates.20-22 Participants were compensated for completing baseline assessments.

Measures

Participants provided demographic information including sex, age, race, education, and marital status. Height was measured with a mounted stadiometer, and weight was assessed using a digital scale. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Axis I diagnoses were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I).23 The SCID-II24 was administered to assess DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders. Interviewers were master's and doctoral level clinicians who received training with the SCID training tapes and ongoing supervision from a doctoral level, licensed clinical psychologist.

Childhood maltreatment was assessed using the 28-item Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ, short version),25 a brief self-report inventory that evaluates childhood (defined as age < 18 years) maltreatment in 5 domains: emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. Respondents rate statements on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from “never true” to “very often true.” Most items are phrased in objective, non-evaluative terms (e.g., “When I was growing up, someone tried to touch me in a sexual way, or tried to make me touch them”), although some items rely on the participant's subjective assessment (e.g., “When I was growing up, I believe that I was sexually abused”). Psychometric properties of the CTQ, including its internal consistency, test-retest reliability, factor structure, convergent validity with structured interviews, and corroboration using independent data have been well documented.25-28 Consistent with previous studies of bariatric surgery patients,9,10 we used established cut-points for each CTQ scale to identify patients with clinically significant maltreatment histories. Specifically, patients scoring at or above the following cut-points with sensitivity and specificity ≥ 0.85 were classified as having a history of childhood maltreatment: emotional abuse = 10; physical abuse = 8; sexual abuse = 8; emotional neglect = 15; physical neglect = 8.26

Analytic plan

First, descriptive statistics were conducted to characterize the prevalence of childhood maltreatment in the sample. Chi square analysis was used to determine whether rates of maltreatment differed by sex. Consistent with previous research,25 in cases in which a participant completed only 4 of the 5 items comprising a specific abuse scale (e.g., physical abuse), total scores were prorated by multiplying by 5/4. Analyses were performed with prorated cases included and excluded, and results were the same (data available upon request).

Next, we used analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and logistic regression models to evaluate the association between childhood maltreatment and: 1) number of lifetime Axis I diagnoses (Note: Lifetime diagnosis refers to any history of having met full diagnostic criteria for an Axis I disorder, and includes participants with a disorder at the time of preoperative evaluation); 2) rates of lifetime mood disorder, anxiety disorder, substance use disorder, and eating disorder diagnoses; and 3) rates of Cluster A (i.e., paranoid, schizoid, schizotypal); Cluster B (i.e., antisocial, borderline, narcissistic; Note: No patient met criteria for histrionic personality disorder), Cluster C (i.e., avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive), and any personality disorder diagnoses. BMI was entered as a covariate in all tests examining the association between childhood maltreatment and psychiatric morbidity because BMI was significantly correlated with Axis I psychopathology in our previous report19 and was associated with increased rates of Axis I and II psychopathology in the current sample (data available upon request). Wald's statistic was used to determine whether childhood maltreatment was associated with specific forms of Axis I and II psychopathology in the logistic regression models. To reduce the risk of Type I error, we used a Bonferroni-adjusted alpha-level for each set of analyses (i.e., two-tailed alpha set at P = 0.05/number of comparisons). Statistics were conducted using SPSS 14.0 for Windows.

Results

Rates of childhood maltreatment

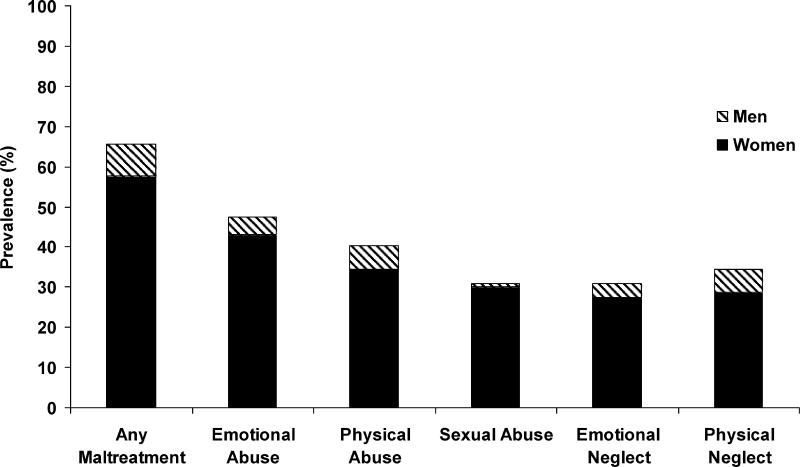

Figure 1 presents rates of childhood maltreatment in the present study. Approximately two-thirds of the sample (65.7%; n = 151) reported some form of childhood maltreatment at or above established cut-points. There were no significant sex differences in rates of physical abuse (P = 0.53) or emotional or physical neglect (P = 0.12 and 0.87, respectively). Women were significantly more likely than men to report childhood emotional abuse (51.8% vs. 25.6%; Χ2[1] = 8.91, P = 0.003) and sexual abuse (36.1% vs. 5.1%; Χ2[1] = 14.58, P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Rates of Childhood Maltreatment by Gender in Bariatric Surgery Candidates (N = 230)*

*Women comprise the majority of the sample (n = 191; 83.0%).

Childhood maltreatment and Axis I psychopathology

As presented in Table 1, across all five forms of maltreatment, individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment had a greater number of Axis I diagnoses than did those without, although the effect for physical neglect was no longer significant after controlling for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni-adjusted alpha level set at P = 0.01). Next, we examined the association between childhood maltreatment and specific forms of Axis I psychopathology in bariatric surgery candidates (Table 2). After controlling for BMI and multiple comparisons (Bonferroni-adjusted alpha-level set at P = 0.003), emotional abuse and sexual abuse were associated with increased rates of mood disorder and anxiety disorder diagnoses. Emotional neglect also was associated with increased rates of mood disorder diagnoses, and physical abuse was associated with increased rates of substance use disorders.

Table 1.

Number of Axis I Diagnoses in Relation to Childhood Maltreatment History in Bariatric Surgery Candidates*

| CTQ Scale† |

Maltreatment History M (SD) |

No Maltreatment History M (SD) |

F (1, 227) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Abuse | 2.73 (2.35) | 1.14 (1.55) | 32.45 | < 0.001§ |

| Physical Abuse | 2.58 (2.28) | 1.43 (1.87) | 14.47 | < 0.001§ |

| Sexual Abuse | 2.75 (2.28) | 1.52 (1.93) | 18.25 | < 0.001§ |

| Emotional Neglect | 2.62 (2.20) | 1.57 (2.01) | 9.01 | 0.003§ |

| Physical Neglect | 2.34 (2.05) | 1.67 (2.13) | 4.64‡ | 0.032 |

Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed with BMI as a covariate.

CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire.

Data from one patient was missing for the physical neglect scale (F [1, 226]).

Statistically significant at Bonferroni-adjusted alpha of P = 0.01.

Table 2.

Associations between Childhood Maltreatment and Axis I Psychopathology in Bariatric Surgery Candidates (N = 230)

| Emotional Abuse | Physical Abuse | Sexual Abuse | Emotional Neglect | Physical Neglect* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axis I Disorder | OR† (95% CI)‡ | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P |

| Mood Disorder | 3.84 (2.20-6.71) | <0.001§ | 2.17 (1.26-3.74) | 0.005 | 2.56 (1.43-4.58) | 0.002§ | 2.78 (1.54-5.01) | 0.001§ | 2.06 (1.18-3.61) | 0.011 |

| Anxiety Disorder | 3.48 (2.00-6.19) | <0.001§ | 1.97 (1.13-3.43) | 0.017 | 2.70 (1.51-4.85) | 0.001§ | 2.07 (1.15-3.72) | 0.015 | 1.96 (1.11-3.45) | 0.021 |

| Substance Use Disorder | 2.15 (1.18-3.91) | 0.012 | 2.59 (1.42-4.71) | 0.002§ | 2.50 (1.35-4.61) | 0.004 | 2.11 (1.14-3.91) | 0.017 | 1.38 (0.75-2.52) | 0.300 |

| Eating Disorder | 2.17 (1.18-3.99) | 0.013 | 1.17 (0.64-2.13) | 0.610 | 1.68 (0.91-3.12) | 0.098 | 1.57 (0.84-2.94) | 0.157 | 0.97 (0.52-1.81) | 0.928 |

Data from one patient was missing for the physical neglect scale (N = 229).

OR = Odds ratio comparing lifetime rates of Axis I clinical disorders in bariatric surgery candidates with and without a specific form of childhood maltreatment. Odds ratios are adjusted for baseline BMI.

CI = Confidence interval.

Statistically significant at Bonferroni-adju ted alpha of P = 0.003.

To better understand the association between childhood maltreatment and specific forms of Axis I psychopathology in bariatric surgery candidates, we calculated lifetime prevalence rates for individual mood and anxiety disorder diagnoses in patients with and without a history of emotional and sexual abuse, as well as emotional neglect (Note: Emotional neglect comparisons were restricted to mood disorders because there was no significant association between emotional neglect and anxiety disorders). Although power limitations preclude statistical comparison of prevalence rates in the current sample, examination of the data presented in Table 3 indicates that individuals with a history of childhood maltreatment had elevated rates of both unipolar and bipolar mood disorders relative to individuals with no maltreatment history. With respect anxiety disorder diagnoses, data indicate that emotional abuse was associated with a full range of anxiety psychopathology, while the relation between sexual abuse and anxiety disorders was largely driven by elevated rates of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Table 3.

Lifetime Prevalence of Mood and Anxiety Disorder Diagnoses in Relation to Childhood History of Emotional and Sexual Abuse and Emotional Neglect in Bariatric Surgery Candidates

| Emotional Abuse | Sexual Abuse | Emotional Neglect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 109) |

No (n = 121) |

Yes (n = 71) |

No (n = 159) |

Yes (n = 71) |

No (n = 159) |

|

| Mood Disorders | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 58 (53.2) | 34 (28.1) | 34 (47.9) | 58 (36.5) | 39 (54.9) | 53 (33.3) |

| Dysthymia | 5 (4.6) | 0 (--) | 4 (5.6) | 1 (0.6) | 3 (4.2) | 2 (1.3) |

| Bipolar I or II Disorder | 8 (7.3) | 1 (0.8) | 7 (9.9) | 2 (1.3) | 5 (7.0) | 4 (2.5) |

| Anxiety Disorders | ||||||

| Panic Disorder | 35 (32.1) | 16 (13.2) | 22 (31.0) | 29 (18.2) | -- | -- |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | 15 (13.8) | 6 (5.0) | 15 (21.1) | 6 (3.8) | -- | -- |

| Social Phobia | 10 (9.2) | 6 (5.0) | 9 (12.7) | 7 (4.4) | -- | -- |

| Specific Phobia | 13 (11.9) | 4 (3.3) | 7 (9.9) | 10 (6.3) | -- | -- |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | 6 (5.5) | 2 (1.7) | 2 (2.8) | 6 (3.8) | -- | -- |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 9 (8.3) | 4 (3.3) | 6 (8.5) | 7 (4.4) | -- | -- |

| Agoraphobia without Panic | 8 (7.3) | 3 (2.5) | 4 (5.6) | 7 (4.4) | -- | -- |

Childhood maltreatment and Axis II psychopathology

Finally, we examined the association between childhood maltreatment and Axis II personality disorders in bariatric surgery candidates. As presented in Table 4, after controlling for BMI and multiple comparisons (Bonferroni-adjusted alpha-level set at P = 0.003), there was no significant association between any form of childhood maltreatment and personality psychopathology in our sample.

Table 4.

Associations between Childhood Maltreatment and Axis II Psychopathology in Bariatric Surgery Candidates (N = 230)

| Emotional Abuse | Physical Abuse | Sexual Abuse | Emotional Neglect | Physical Neglect* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axis II Disorder | OR† (95% CI)‡ | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P |

| Cluster A | 4.30 (1.36-13.62) | 0.013 | 2.46 (0.91-6.66) | 0.076 | 3.98 (1.47-10.75) | 0.006 | 3.09 (1.14-8.33) | 0.026 | 3.85 (1.36-10.85) | 0.011 |

| Cluster B | 4.92 (1.58-15.36) | 0.006 | 1.84 (0.72-4.67) | 0.202 | 1.55 (0.61-3.99) | 0.360 | 1.47 (0.56-3.84) | 0.434 | 2.00 (0.79-5.04) | 0.143 |

| Cluster C | 1.49 (0.81-2.75) | 0.205 | 1.04 (0.56-1.92) | 0.912 | 1.54 (0.82-2.91) | 0.180 | 1.34 (0.70-2.54) | 0.379 | 1.60 (0.86-2.97) | 0.140 |

| Any Personality Disorder | 2.17 (1.22-3.87) | 0.008 | 1.23 (0.70-2.19) | 0.473 | 1.99 (1.10-3.60) | 0.023 | 1.49 (0.82-2.72) | 0.193 | 1.68 (0.94-3.01) | 0.082 |

Data from one patient was missing for the physical neglect scale (N = 229).

OR = Odds ratio comparing lifetime rates of Axis II personality disorders in bariatric surgery candidates with and without a specific form of childhood maltreatment. Odds ratios are adjusted for baseline BMI.

CI = Confidence interval.

Discussion

This study is the first to use state-of-the-art methodology to evaluate the relation between childhood maltreatment and Axis I and II psychiatric disorders in obese patients presenting for bariatric surgery. Our findings converge with previous research in documenting high rates of childhood maltreatment in this group. Indeed, the overall rate of childhood maltreatment in our sample (65.7%) is nearly identical to that reported by Grilo and colleagues in two previous investigations that have used the CTQ to evaluate childhood maltreatment in bariatric surgery patients.9,10 Furthermore, this study extends previous research by documenting that childhood maltreatment is associated with elevated rates of Axis I clinical diagnoses among individuals seeking weight-loss surgery, even after controlling for initial BMI. Specifically, patients reporting a history of emotional, physical, or sexual abuse, or emotional neglect had a significantly greater number of lifetime Axis I diagnoses than did patients without those specific forms of childhood maltreatment. Moreover, a history of emotional or sexual abuse, or emotional neglect was associated with increased rates of lifetime mood disorder diagnoses in our sample. Emotional and sexual abuse also were associated with increased rates of lifetime anxiety disorder diagnoses, while physical abuse was associated with increased rates of substance use disorders. These findings are consistent with a large body of research documenting the association between childhood maltreatment and a broad range of Axis I clinical disorders in both community16,17,29,30 and treatment-seeking samples.31,32

It is somewhat surprising that eating disorders were not significantly associated with childhood maltreatment in this study. Prospective longitudinal research using general population samples has documented that a history of childhood maltreatment is associated with increased risk for the development of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder.2 Nevertheless, previous work examining the clinical correlates of childhood maltreatment in bariatric surgery candidates generally has failed to find an association with eating disorder symptoms9,10 (but see Gustafson et al.12). One explanation for these discrepant findings may be that eating disorders are difficult to assess in seriously obese individuals seeking bariatric surgery. Although recurrent binge eating is common in this group,33,34 there has been debate in the empirical literature as to whether this behavior constitutes a separate psychiatric disorder or is merely a marker of more general psychopathology.35 Findings from the present study suggest that with respect to a history of childhood maltreatment, disorders of lifetime mood, anxiety, and substance use may have greater clinical significance among bariatric surgery patients than do eating disorders.

This study is the first to our knowledge to evaluate the association between childhood maltreatment and Axis II personality disorders in bariatric surgery candidates. Although we found no statistically significant relationship between childhood maltreatment and Axis II psychopathology after controlling for multiple comparisons, there were a number of trend-level associations that suggest a need for future research in this area. For example, using a less stringent alpha-level of P = 0.05, our data suggest that emotional and sexual abuse, as well as emotional and physical neglect, may be associated with increased rates of personality psychopathology in bariatric surgery candidates. Given the well-documented association between childhood maltreatment and personality disorders in general population samples,14,15 there is a need for additional research to elucidate the relation between different forms of childhood maltreatment and personality disturbance in patients presenting for weight-loss surgery.

Although this study has a number of strengths including the use of standardized instruments to evaluate childhood maltreatment and a broad range of Axis I and II psychiatric disorders, there are several limitations that must be considered when interpreting the findings. First, because participants were seeking weight-loss surgery at a large, urban medical center, our results may not be generalizable to severely obese individuals seeking non-surgical weight-loss treatments, or to non-treatment-seeking community populations. Second, although the CTQ is a well-validated measure,25,28 it is possible that retrospective self-reports of childhood maltreatment may be vulnerable to recall bias, especially among individuals with current psychopathology. Nevertheless, we note that rates of childhood maltreatment in the present study were remarkably similar to those reported by two previous investigations that used the CTQ in samples of bariatric surgery patients.9,10 Third, although the overall rate of childhood maltreatment in the present sample was high (65.7%), prevalence rates for some specific forms of maltreatment (e.g., sexual abuse, emotional neglect) were fairly low. Thus, it is possible that power to evaluate the association between certain forms of childhood maltreatment and Axis I and II disorders was limited. Finally, analyses focusing on Axis I psychopathology included both current and past diagnoses. Although the chronic nature of many psychiatric disorders suggests that a past history of diagnosis is clinically relevant, there is a need for future research to evaluate the relation between childhood maltreatment and rates of psychiatric disorders at presentation for bariatric surgery.

In summary, this study confirms that childhood maltreatment is prevalent in obese individuals presenting for weight-loss surgery and is associated with increased rates of Axis I psychopathology, including lifetime mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders. Future research is needed to elucidate the long-term impact of childhood maltreatment in this group. Although recent studies have found little evidence for a direct relationship between childhood maltreatment and outcome following bariatric surgery,10,13,36 work from our research group and others indicates that a history of psychiatric disorder is associated with poorer functional health status at treatment presentation19 and smaller decreases in BMI following weight-loss surgery.37,38 Thus, childhood maltreatment may exert an indirect effect on bariatric surgery outcome via its association with increased rates of Axis I clinical disorders. Future prospective studies should include evaluation of a broad range of mental health and childhood experiences in order to tease apart the nature of the relationships between these factors and their potential impact on post-surgical outcomes. This may lead to development of better surgery screening and preparation programs, as well as targeted interventions to optimize surgery outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Research supported by a seed money grant from the University of Pittsburgh Obesity and Nutrition Research Center (P30 DK46204) and a career development award from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K23 DK62291).

References

- 1.Lissau I, Sorensen TIA. Parental neglect during childhood and increased risk of obesity in young adulthood. Lancet. 1994;343:324–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kassen S, et al. Childhood adversities associated with risk for eating disorders or weight problems during adolescence or early adulthood. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:394–400. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Anda RF, et al. Body weight and obesity in adults and self-reported abuse in childhood. Int J Obes. 2002;26:1075–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jia H, Li JZ, Leserman J, et al. Relationship of abuse history and other risk factors with obesity among female gastrointestinal patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:872–7. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000030102.19372.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yanovski SZ, Nelson JE, Dubbert BK, et al. Association of binge eating disorder and psychiatric comorbidity in obese subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1472–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.10.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grilo CM, Masheb RM. Childhood psychological, physical, and sexual maltreatment in outpatients with binge eating disorder: frequency and associations with gender, obesity, and eating related psychopathology. Obes Res. 2001;9:320–5. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Felitti VJ. Long-term medical consequences of incest, rape, and molestation. South Med J. 1991;84:328–31. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Sarwer DB, et al. Comparison of psychosocial status in treatment-seeking women with class III vs. class I-II obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:138–45. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Brody M, et al. Childhood maltreatment in extremely obese male and female bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Res. 2005;13:123–30. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grilo CM, White MA, Masheb RM, et al. Relation of childhood sexual abuse and other forms of maltreatment to 12-month postoperative outcomes in extremely obese gastric bypass patients. Obes Surg. 2006;16:454–60. doi: 10.1381/096089206776327288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maddi SR, Khoshaba DM, Persico M, et al. Psychosocial correlates of psychopathology in a national sample of the morbidly obese. Obes Surg. 1997;7:397–404. doi: 10.1381/096089297765555377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gustafson TB, Gibbons LM, Sarwer DB, et al. History of sexual abuse among bariatric surgery candidates. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:369–74. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oppong BA, Nickels MW, Sax HC. The impact of a history of sexual abuse on weight loss in gastric bypass patients. Psychosomatics. 2006;47:108–11. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.47.2.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Brown J, et al. Childhood maltreatment increases risk for personality disorders during early adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:600–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Smailes EM, et al. Childhood verbal abuse and risk for personality disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42:16–23. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.19755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendler KS, Bulik CM, Silberg J, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and adult psychiatric and substance use disorders in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:953–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.10.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Streiner DL, et al. Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1878–83. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afifi TO, Brownridge DA, Cox BJ, et al. Physical punishment, childhood abuse and psychiatric disorders. Child Abuse Negl. 2006;30:1093–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Levine MD, et al. Psychiatric disorders among bariatric surgery candidates: relationship to obesity and functional health status. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:328–34. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bauman LJ. Collecting data by telephone interviewing. Dev Behav Pediatrics. 1993;14:256–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Comparability of telephone and face-to-face interviews in assessing Axis I and Axis II disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1593–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keel PK, Crow S, Davis TL, et al. Assessment of eating disorders: comparison of interview and questionnaire data from a long-term follow-up study of bulimia nervosa. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:1043–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker EA, Unutzer J, Rutter C, et al. Costs of health care use by women HMO members with a history of childhood abuse and neglect. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:609–13. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scher CD, Stein MB, Asmundson GJG, et al. The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in a community sample: psychometric properties and normative data. J Trauma Stress. 2001;14:843–57. doi: 10.1023/A:1013058625719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:169–90. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Widom CS. Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1223–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molnar BE, Buka SL, Kessler RC. Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:753–60. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernet CZ, Stein MB. Relationship of childhood maltreatment to the onset and course of major depression in adulthood. Depress Anxiety. 1999;9:169–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hyman SM, Garcia M, Sinha R. Gender specific associations between types of childhood maltreatment and the onset, escalation, and severity of substance use in cocaine dependent adults. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32:655–64. doi: 10.1080/10623320600919193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarwer DB, Cohn NI, Gibbons LM, et al. Psychiatric diagnoses and psychiatric treatment among bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1148–56. doi: 10.1381/0960892042386922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niego SH, Kofman MD, Weiss JJ, et al. Binge eating in the bariatric surgery population: a review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:349–59. doi: 10.1002/eat.20376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stunkard AJ, Allison KC. Binge eating disorder: disorder or marker? Int J Eat Disord. 2003;34:S107–16. doi: 10.1002/eat.10210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buser A, Dymek-Valentine M, Hilburger J, et al. Outcome following gastric bypass surgery: impact of past sexual abuse. Obes Surg. 2004;14:170–4. doi: 10.1381/096089204322857519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinzl JF, Schrattenecker M, Traweger C, et al. Psychosocial predictors of weight loss after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1609–14. doi: 10.1381/096089206779319301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Levine MD, et al. Relationship of psychiatric disorders to 6-month outcomes after gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.03.003. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]