Abstract

The therapeutic potential of ginseng has been studied extensively, and ginsenosides, the active components of ginseng, are shown to be involved in modulating multiple physiological activities. This article will review the structure, systemic transformation and bioavailability of ginsenosides before illustration on how these molecules exert their functions via interactions with steroidal receptors. The multiple biological actions make ginsenosides as important resources for developing new modalities. Yet, low bioavailability of ginsenoside is one of the major hurdles needs to be overcome to advance its use in clinical settings.

Review

Background

Panax ginseng (Renshen, Chinese ginseng) is commonly used either by itself or in combination with other medicinal ingredients as a key herb in Chinese medicine. A member of the Araliaceae family, the genus name Panax was derived from the Greek word meaning "all-healing" first coined by the Russian botanist Carl A. Meyer. The Panax family consists of at least nine species, including P. ginseng, Panax quinquefolium (Xiyangshen, American ginseng), Panax notoginseng (Sanqi) and Panax japonicus (Japanese ginseng). The worldwide sale of ginseng products has estimated to reach US$ 300 million in 2001 [1,2].

Ginseng modulates blood pressure, metabolism and immune functions [3-6]. The action mechanism of ginseng had not been known until ginsenosides were isolated in 1963 [7,8]. Much effort has since been focused on evaluating the function and elucidating the molecular mechanism of each ginsenoside. Number of publications on ginseng and ginsenosides has been growing exponentially since 1975 according to the Pubmed entry.

Ginsenosides are the pharmacologically active components in ginseng

Ginsenosides are triterpene saponins. Most ginsenosides are composed of a dammarane skeleton (17 carbons in a four-ring structure) with various sugar moieties (e.g. glucose, rhamnose, xylose and arabinose) attached to the C-3 and C-20 positions [9,10]. Ginsenosides are named as 'Rx', where the 'R' stands for the root and the 'x' describes the chromatographic polarity in an alphabetical order [7], for example, Ra is the least polar compound and Rb is more polar than Ra. Over 30 ginsenosides have been identified and classified into two categories: (1) the 20(S)-protopanaxadiol (PPD) (Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, Rc, Rd, Rg3, Rh2, Rs1) and (2) the 20(S)-protopanaxatriol (PPT) (Re, Rf, Rg1, Rg2, Rh1). The difference between PPTs and PPDs is the presence of carboxyl group at the C-6 position in PPDs [9,10]. Moreover, several rare ginsenosides, such as the ocotillol saponin F11 (24-R-pseudoginsenoside) [11] and the pentacyclic oleanane saponin Ro (3,28-O-bisdesmoside) [12] have also been identified.

The quality and composition of ginsenosides in the ginseng plants are influenced by a range of factors bhsuch as the species, age, part of the plant, cultivation method, harvesting season and preservation method [13,14]. For example, ginsenoside Rf is unique to Asian ginseng while F11 is found exclusively in American ginseng. Thus the Rf/F11 ratio is used as a phytochemical marker to distinguish American ginseng from Asian ginseng [15,16]. The overall saponin content in ginseng is directly proportional to its age, reaching a peak level at around 6 years of age [17,18]. Most harvested ginseng roots are air-dried while some are steamed at 100°C for two to four hours before drying, which gives the ginseng a darker appearance known as red ginseng. The red ginseng has a unique saponin profile, with emerging ginsenosides Ra1, Ra2, Ra3, Rf2, Rg4, Rg5, Rg6, Rk1, Rs1 and Rs2 being likely the results of heat transformation and deglycosylation of naturally occurring ginsenosides [19-24]. The presence of these compounds may confirm the folk knowledge that red ginseng is of higher medicinal values than the white one [25].

Sun ginseng is a new type of processed ginseng that is steamed at 120°C. The new process aimed to increase the levels of anti-tumor ginsenosides Rg3, Rg5 and Rk1 [26-30]. Moreover, the butanol-soluble fraction of Sun ginseng is formulated into KG-135 which contains Rk3 Rs3, Rs4, Rs5, Rs6 and Rs7 in addition to the major anti-tumor ginsenosides [31].

Standardized ginseng extracts

To avoid variability among preparations, many researchers use commercially available standardized ginseng extracts. Two commonly used standardized extracts are G115 from P. ginseng (total ginsenoside adjusted to 4%) (Pharmaton SA, Switzerland) and NAGE from P. quinquefolius (total ginsenoside content adjusted to 10%) (Canadian Phytopharmaceuticals Corporation, Canada). Studies on these two ginseng extracts using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) found ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, Re and Rg1 in both G115 and NAGE, and ginsenoside Rg2 in G115 only. To compare between G115 and NAGE, G115 has higher Rg1, but NAGE has higher in Rb1 and Re [32-34].

Ginsenosides are part of the defense mechanisms in ginseng

Similar to plants that produce insect repellents and anti-microbial substances as part of their defense mechanisms, e.g. nicotine from tobacco leaves [35], rotenone from derris tree roots [36], pyrethroids from chrysanthemum flowers [37], and triterpenoids from neem tress [38], evidence suggests that ginsenosides may protect ginseng. Addition of methyl jasmonate (a plant-specific signaling molecule expressed during insect and pathogenic attacks) into ginseng in vitro cultures enhances ginsenoside production [39-41]. Naturally occurring ginsenosides are antimicrobial and antifungal; the bitter taste of ginsenosides makes them antifeedant [42-46].

Furthermore, ginsenosides may act as ecdysteroids, the insect molting and metamorphosis hormones, due to the structural similarities between the two groups of chemicals. The ecdysteroids have a steroid backbone with a C-20 sugar side-chain and a C-3 hydroxyl group [47] resembling the structure of most of the PPT-type ginsenosides such as Rg1 and several metabolites of PPDs such as compound Y and compound K. Ecdysteroids differ from ginsenosides in the C-6 position which is occupied by an oxygen group is in the former and a hydrogen or hydroxyl group in the latter [47]. Such difference, however, has minor and non-significant influence on ecdysteroid receptor binding affinity as demonstrated by biochemical analysis [47,48]. The structural similarity suggests that certain naturally occurring ginsenosides may disrupt insects' life cycle by binding to ecdysteroid receptor.

Biotransformation of ginsenosides

Treatment of various cultured cells by ginsenosides revealed multiple bioactivities, including neuroprotection [49-53], antioxidation [54-56], angiogenesis modulation [57-59] and cytotoxicity [60-62]. However, biotransformation may be required before ginsenosides becoming active in mammalian systems. Recent studies demonstrated that ginsenoside metabolites had greater biological effects than ginsenosides [63-65]. Anti-tumor activities of Rh2 and PD, which are the metabolites of Rg3, are more potent than those of ginsenoside Rg3 [64]. Ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rg1 and Re do not possess the same human liver enzyme cytochrome P450 inhibitory effects of compound K, PT and PD which are the intestinal metabolites of PPTs and PPDs [65].

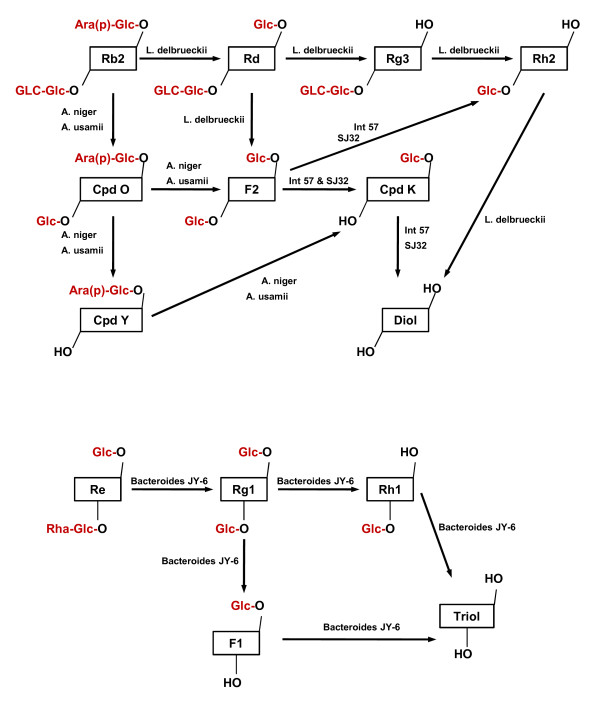

Major ginsenosides, such as Rg1, Rg3, Rb1, Re and Rc, are treated as antigens by mammalian systems. Antibodies against these ginsenosides have been purified from immunized animals [66-70]. Due to their bulky molecular structures, the ginsenosides are poorly membrane permeable and prone to degradation. Oral consumption of ginseng preparations exposes ginsenosides to acid hydrolysis accompanied by side-reactions, glycosyl elimination and epimerization of C-20 sugar moiety [71,72]. The C-3 or C-20 oligosaccharides are also cleaved by intestinal microflora stepwise from the terminal sugar [72,73]. These intestinal microflora include Prevotella oris [74], Eubacterium A-44 [75], Bifidobacterium sp. [73,76], Bacteroides JY6 [73], Fusbacterium K-60 [73], Lactobacillus delbrueckii sp. [76] and Aspergillus sp. [76]. Following biodegradation, compound K and protopanaxadiol (PPD) are the major metabolites of PPDs while PPTs are converted to F1 and protopanaxatriol (PPT) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Biodegradation of ginsenosides by intestinal microflora. PPDs and PPTs are deglycosylated to end-metabolites protopanaxadiol (PPD) and protopanaxatriol (PPT) respectively. Glc = beta-D-glucopyranosyl; Ara(p) = alpha-L-arabinopyranosyl; Ara(f) = alpha-D-arabinofuranosyl; Rha = alpha-L-rhamnopyranosyl [73-76]

Pharmacokinetic and bioavailability of ginsenosides

How intact and transformed ginsenosides are absorbed and transported to the human system remains elusive. Transport of ginsenosides across the intestinal mucosa is energy-dependent and non-saturable [77-79]. The sodium-dependent glucose co-transporter 1 may be involved in this process [80]. The availability of intact ginsenosides and their metabolites from the intestines is extremely low [81-83]. For example, only 3.29% Rg1 and 0.64% Rb1 are detected in rat serum after oral administration of ginsenosides [78,79], confirming the classic studies by Odani et al. in 1983 [84,85]. Rg1 levels become undetectable within 24 hours of oral consumption while Rb1 levels remain relatively stable for three days [83].

Experiments to increase the bioavailability of ginsenosides include co-administration of ginsenosides with adrenaline [86], emulsification of ginsenosides into lipid-based formulation [87,88] and suppression of p-glycoprotein efflux system [77]. P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance is a major obstacle to effective cancer treatments. As ginsenoside Rg3 blocks drug efflux by inhibiting p-glycoprotein activities and reducing membrane fluidity, it is used to assist cancer chemotherapy [28,89,90].

Ginsenosides are agonists to steroidal receptors

Ginsenosides modulate expressions and functions of receptors such as receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) [91], serotonin receptors (5-HT) [92], NMDA receptors [93] and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR) [94]. Direct interactions of ginsenosides with the receptor ligand-binding sites have only been demonstrated in steroid hormone receptors; ginsenosides Rg1 [58,95,96] and Re [97] are functional ligands of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) while ginsenosides Rh1 and Rb1 are functional ligands of the estrogen receptor (ER), in particular, the ER beta isoform of Rb1 [59,98]. These findings provide an explanation for the aggravation of menopausal symptoms by ginsenosides [99,100] and modulation of the endocrine system in the case of chronic consumption of ginseng [3,4].

Glucocorticoid is a stress hormone to elicit 'fight-or-flight' responses through GR activation. If Rg1 and Re are functional ligands of GR, how is ginseng adaptogenic and antistress? Rg1 and Re may behave as partial agonists to GR. Both Rg1 and Re inhibit the binding of the synthetic glucocorticoid dexamethasone to GR and 100% displacement is possible when ginsenosides are in excess [96,97]. Since Rg1 and Re elicit biological activities that are GR inhibitor RU486 sensitive, indicating these ginsenosides are agonists, but not inhibitors for GR [58,96]. And it is because the steroidal effects of Rg1 and Re are not as prominent as dexamethasone, these ginsenosides are likely to be partial agonist of GR [58,96]. Under physiological conditions, ginsenosides may compensate the insufficient steroidal activities, when the intrinsic ligand is absent or inadequate in the system. On the other hand, ginsenosides can reversibly occupy certain percentage of the steroidal receptor at low affinity to counter the steroidal effects when they co-exist with a large amount of intrinsic ligand.

Moreover, each ginsenoside is able to bind to multiple steroid hormone receptors. In addition to GR, ginsenoside Rg1 acts through ER and elicits cross-talking with insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-IR) in neuronal cells [101]. Effects of ginsenoside Re on cardiac myocytes are related to ER alpha isoform, androgen receptor and progesterone receptor [102]. The end-metabolites PD and PT bind and activate both GR and ER in endothelial cells [103]. The multi-target properties of ginsenosides may explain why ginseng has a wide range of beneficial effects.

Conclusion

As partial agonists to multiple steroidal receptors, ginsenosides are important natural resources to be developed into new modalities, and may replace steroids in the current regimen to lessen undesirable side effects. However, low bioavailablilities of ginsenosides and its metabolites means that most of these compounds do not reach the intended biological system when administered orally. The results of ginsenoside researches will become physiological relevant only when (1) the pure compounds of the ginsenosides is available in large quantities; (2) the ginsenosides are biochemically stabilized to avoid degradation and enhance absorption in the gastrointestinal tract; and/or (3) special delivery methods for the ginsenosides to reach the areas of treatment. Moreover, this review highlighted the necessary of ginsenoside transformation to exert its greatest effects in the mammalian system, thus accelerating this process would help maximizing the remedial effects of ginsenosides. Addressing these two issues in the near future would advance ginseng researches and enhance the possibility for ginseng to be used clinically.

Abbreviations

5-HT: serotonin receptors; AChR: acetylcholine receptor; ER: estrogen receptor; GR: glucocorticoid receptor; HPLC: high performance liquid chromatography; IGF-IR: insulin-like growth factor-1; PD: panaxadiol; PT: panaxatriol; PPD: 20(S)-protopanaxadiol; PPT: 20(S)-protopanaxatriol; RTK: receptor tyrosine kinases

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

KWL and ASTW contributed equally on developing the concept, drafting and editing the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Kar Wah Leung, Email: kwl_melody@yahoo.co.uk.

Alice Sze-Tsai Wong, Email: awong1@hku.hk.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Grant Council, Hong Kong SAR Government (HKBU1/06C) and the Hong Kong University Outstanding Young Researcher Award to ASTW.

References

- Eliason BC, Kruger J, Mark D, Rasmann DN. Dietary supplement users: demographics, product use and medical system interaction. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1997;10:265–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harnack LJ, Rydell SA, Stang J. Prevalence of use of herbal products by adults in the Minneapolis/St Paul, Minn, Metropolitan area. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:688–694. doi: 10.4065/76.7.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CX, Xiao PG. Recent advances on ginseng research in China. J Ethnopharmacol. 1992;36:27–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(92)90057-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attele AS, Wu JA, Yuan CS. Ginseng pharmacology: multiple constituents and multiple actions. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:1685–1693. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(99)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spelman K, Burns J, Nichols D, Winters N, Ottersberg S, Tenborg M. Modulation of cytokine expression by traditional medicines: a review of herbal immunomodulators. Altern Med Rev. 2006;11:128–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang YZ, Shang HC, Gao XM, Zhang BL. A comparison of the ancient use of ginseng in traditional Chinese medicine with modern pharmacological experiments and clinical trials. Phytother Res. 2008;22:851–858. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata S, Fujita M, Itokawa H, Tanako O, Ishii T. Studies on the constituents of Japanese and Chinese Crude Drugs. XI. Panaxadiol, a sapogenin of ginseng roots. (1) Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1963;11:759–761. doi: 10.1248/cpb.11.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata S, Tanaka O, Soma K, Ando T, Iida Y, Nakamura H. Studies on saponins and sapogenins of ginseng. The structure of panaxatriol. Tetrahedron Lett. 1965;42:207–213. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)99595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura H, Kasai R, Tanaka O, Saruwatari Y, Kunihiro K, Fuwa T. Further studies on the dammarane-saponins of ginseng roots. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1984;32:1188–1192. [Google Scholar]

- De Smet PAGM. Herbal remedies. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:2046–2056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namba T, Matsushige K, Morita T, Tanaka O. Saponins of plants of Panax species collected in central Nepal and their chemotaxonomical significance. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1986;34:730–738. doi: 10.1248/cpb.48.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanada S, Kondo N, Shoji J, Tanaka O, Shibata S. Studies on the saponin of ginseng. I. Structures of ginsenoside-Ro, -Rb1, -Rc, and -Rd. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1974;22:421–428. [Google Scholar]

- Lim W, Mudge KW, Vermeylen F. Effects of population, age, and cultivation methods on ginsenoside content of wild American ginseng (Panax quinquefolium) J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:8498–8505. doi: 10.1021/jf051070y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlag EM, Mclntosh MS. Ginsenoside content and variation among and within American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.) populations. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:1510–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Gu C, Zhang H, Awang DVC, Fitzloff JF, Fong HHS, van Breemen RB. Use of high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry to distinguish Panax ginseng C.A. meyer (Asian ginseng) and Panax quinquefolius L. (North American ginseng) Anal Chem. 2000;72:5417–5422. doi: 10.1021/ac000650l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assinewe VA, Baum BR, Gagnon D, Arnason JT. Phytochemistry of wild populations of Panax quinquefolium L. (North American ginseng) J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:4549–4553. doi: 10.1021/jf030042h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldati F, Tanaka O. Panax ginseng: relation between age of plant and content of ginsenosides. Planta Med. 1984;50:351–352. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-969729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court WA, Reynolds LB, Hendel JG. Influence of root age on the concentration of ginsenosides of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolium) Can J Plant Sci. 1996;76:853–855. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko H, Nakanishi K. Proof of the mysterious efficacy of ginseng: basic effects of medical ginseng, Korean red ginseng: its anti-stress action for prevention of disease. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;95:158–162. doi: 10.1254/jphs.FMJ04001X5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai R, Besso H, Tanaka O, Saruwatari Y, Fuwa T. Saponins of red ginseng. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1983;31:2120–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SI, Park JH, Ryu JH, Park JD, Lee YH, Park JH, Kim TH, Baek NI. Ginsenoside Rg5, a genuine dammarane glycoside from Korean red ginseng. Arch Pharm Res. 1996;19:551–553. doi: 10.1007/BF02986026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu JH, Park JH, Eun JH, Jung JH, Sohn DH. A dammarane glycoside from Korean red ginseng. Phytochemistry. 1997;44:931–933. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(96)00661-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park JD, Lee YH, Kim SI. Ginsenoside Rf2, a new dammarane glycoside from Korean red ginseng (Panax ginseng) Arch Pharm Res. 1998;21:615–617. doi: 10.1007/BF02975384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon SW, Han SB, Park IH, Kim JM, Park MK, Park JH. Liquid chromatographic determination of less polar ginsenosides in processed ginseng. J Chromatogr A. 2001;921:335–339. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)00869-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WY, Kim JM, Han SB, Lee SK, Kim ND, Park MK, Kim CK, Park JH. Steaming of ginseng at high temperature enhances biological activity. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:1702–1704. doi: 10.1021/np990152b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KY, Lee YH, Kim SI, Park JH, Lee SK. Ginsenoside-Rg5 suppresses cyclin E-dependent protein kinase activity via up-regulating p21Cip/WAF1 and down-regulating cyclin E in SK-HEP-1 cells. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:1067–1072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu WK, Xu SX, Che CT. Anti-proliferative effect of ginseng saponins on human prostate cancer cell line. Life Sci. 2000;67:1297–1306. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(00)00720-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu TM, Xin Y, Cui MH, Jiang X, Gu LP. Inhibitory effect of ginsenoside Rg3 combined with cyclophosphamide on growth and angiogenesis of ovarian cancer. Chinese Med J (Engl) 2007;120:584–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Kwon HC, Ko H, Park JH, Kim HY, Yoo JH, Yang HO. Anti-tumor activity of the ginsenoside Rk1 in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells through inhibition of telomerase activity and induction of apoptosis. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31:826–830. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo JH, Kwon HC, Kim YJ, Park JH, Yang HO. KG-135, enriched with selected ginsenosides, inhibits the proliferation of human prostate cancer cells in culture and inhibits xenograft growth in athymic mice. Cancer Lett. 2010;289:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SA, Kim EH, Na HK, Surh YJ. KG-135 inhibits COX-2 expression by blocking the activation of JNK and AP-1 in phorbol ester-stimulated human breast epithelial cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1095:545–553. doi: 10.1196/annals.1397.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler SJ, Cutler HG. Biologically Active Natural Products: Pharmaceuticals. New York: CRC Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hall T, Lu ZZ, Yat PN, Fitzloff JF, Arnason JT, Awang DVC, Fong HHS, Blumenthal M. Evaluation of consistency of standardized Asian ginseng products in the ginseng evaluation program. HerbalGram. 2001;52:31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Chang TKH, Chen J, Benetton SA. In vitro effect of standardized ginseng extracts and individual ginsenosides on the catalytic activity of human CYP1A1, CYP1A2 and CYP1B1. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:378–384. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova H, Ortiz C, Peláez C, Vallejo A, Moreno ME, Acevedo M. Insecticide formulations based on nicotine oleate stabilized by sodium caseinate. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:6389–6394. doi: 10.1021/jf0257244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukami H, Nakajima M. In: Naturally Occurring Insecticides. Jacobson M, Crosby DG, editor. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1971. Rotenone and rotenoids; p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott M. Properties and applications of pyrethroids. Environ Health Perspect. 1976;14:1–13. doi: 10.2307/3428357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aerts RJ, Mordue AJ. Feeding deterrence and toxicity of neem triterpenoids. J Chem Ecol. 1997;23:2117–2132. doi: 10.1023/B:JOEC.0000006433.14030.04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creelman RA, Mullet JE. Biosynthesis and action of jasmonates in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:355–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazon J, Cusido RM, Bonfill M, Mallol A, Moyano E, Morales C, Pinol MT. Elicitation of different Panax ginseng transformed root phenotypes for an improved ginsenoside production. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2003;41:1019–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2003.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW, Jung JD, Ha YI, Park HW, In DS, Chung HJ, Liu JR. Analysis of transcripts in methyl jasmonate-treated ginseng hairy roots to identify genes involved in the biosynthesis of ginsenosides and other secondary metabolites. Plant Cell Rep. 2005;23:557–566. doi: 10.1007/s00299-004-0845-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicol RW, Traquair JA, Bernards MA. Ginsenosides as host resistance factors in American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) Can J Bot. 2002;80:557–562. doi: 10.1139/b02-034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katerere DR, Gray AI, Nash RJ, Waigh RD. Antimicrobial activity of pentacyclic triterpenes isolated from African Combretaceae. Phytochemistry. 2003;63:81–88. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallvadhani UV, Mahapatra A, Raja SS, Manjula C. Antifeedant activity of some pentacyclic triterpene acids and their fatty acid ester analogues. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:1952–1955. doi: 10.1021/jf020691d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernards MA, Yousef LF, Nicol RW. In: Allelochemicals: Biological Control of Plant Pathogens and Diseases. Inderjit, Mukerji KG, editor. Netherlands: Springer; 2006. The allelopathic potential of ginsenosides; pp. 157–175. full_text. [Google Scholar]

- Sung WS, Lee DG. In vitro candidacidal action of Korean red ginseng saponins against candida albicans. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31:139–143. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferro N, Tacoronte JE, Reinard T, Bultinck P, Montero LA. Structure-activity analysis on ecdysteroids: a structure and quantum chemical approach based on two biological systems. J Mol Struct: THEOCHEM. 2005;758:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.theochem.2005.10.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harada T, Nakagawa Y, Akamatsu M, Miyagawa H. Evaluation of hydrogen bonds of ecdysteroids in the ligand-receptor interactions using a protein modeling system. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17:5868–5873. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudakewich M, Ba F, Benishin CG. Neurotrophic and neuroprotective actions of ginsenosides Rb1 and Rg1. Planta Med. 2001;67:533–537. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XC, Zhu YG, Zhu LA, Huang C, Chen Y, Chen LM, Fang F, Zhou YC, Zhao CH. Ginsenoside Rg1 attenuates dopamine-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells by suppressing oxidative stress. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;473:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(03)01945-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang YP, Jeong HG. Ginsenoside Rb1 protects against 6-hydroxydopamine-induced oxidative stress by increasing heme oxygenase-1 expression through an estrogen receptor-related PI3K/Akt/Nrf2-dependent pathway in human dopaminergic cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;242:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge KL, Chen WF, Xie JX, Wong MS. Ginsenoside Rg1 protects against 6-OHDA-induced toxicity in MES23.5 cells via Akt and ERK signaling pathways. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;127:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JR, Tao YF, Lou S, Wu ZM. Protective effects of ginsenoside Rb(3) on oxygen and glucose deprivation-induced ischemic injury in PC12 cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2010;31:273–280. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie JT, Shao ZH, Vanden Hoek TL, Chang WT, Li J, Mehendale S, Wang CZ, Hsu CW, Becker LB, Yin JJ, Yuan CS. Antioxidant effects of ginsenoside Re in cardiomyocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;532:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie XS, Liu HC, Yang M, Zuo C, Deng Y, Fan JM. Ginsenoside Rb1, a panoxadiol saponin against oxidative damage and renal interstitial fibrosis in rats with unilateral ureteral obstruction. Chin J Integr Med. 2009;15:133–140. doi: 10.1007/s11655-009-0133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D, Wu L, Li CR, Wang XW, Ma YJ, Zhong ZY, Zhao HB, Cui J, Xun SF, Huang XL, Zhou Z, Wang SQ. Ginsenoside Rg1 protects rat cardiomyocyte from hypoxia/reoxygenation oxidative injury via antioxidant and intracellular calcium homeostasis. J Cell Biochem. 2009;108:117–124. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S, Toh SA, Sellers LA, Skepper JN, Koolwijk P, Leung HW, Yeung HW, Wong RNS, Sasisekharan R, Fan TPD. Modulating angiogenesis: The Yin and the Yang in ginseng. Circulation. 2004;110:1219–1225. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140676.88412.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung KW, Pon YL, Wong RNS, Wong AST. Ginsenoside-Rg1 induces vascular endothelial growth factor expression through glucocorticoid receptor-related phosphatidylinositol 3-kinse/Akt and β-catenin/TCF-dependent pathway in human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36280–36288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606698200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung KW, Cheung LWT, Pon YL, Wong RNS, Mak NK, Fan TPD, Au SCL, Tombran-Tink J, Wong AST. Ginsenoside-Rb1 inhibits angiogenesis by regulating pigment epithelium-derived factor through the beta estrogen receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:207–215. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZG, Sun HX, Ye YP. Ginsenoside Rd from Panax notoginseng is cytotoxic towards HeLa cancer cells and induces apoptosis. Chem Biodivers. 2006;3:187–197. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200690022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitts DD, Popovich DG, Hu C. Characterizing the mechanism for ginsenoside-induced cytotoxicity in cultured leukemia (THP-1) cells. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;85:1173–1183. doi: 10.1139/Y07-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei J, Li X, Gong XJ, Zheng YN. Isolation, synthesis and structures of cytotoxic ginsenoside derivatives. Molecules. 2007;12:2140–2150. doi: 10.3390/12092140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovich DG, Kitts DD. Structure-function relationship exists for ginsenosides in reducing cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis in the human leukemia (THP-1) cell line. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;406:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00398-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae EA, Han MJ, Kim EJ, Kim DH. Transformation of ginseng saponins to ginsenoside Rh2 by acids and human intestinal bacteria and biological activities of their transformants. Arch Pharm Res. 2004;27:61–67. doi: 10.1007/BF02980048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhang JW, Li W, Ma H, Sun J, Deng MC, Yang L. Ginsenoside metabolites, rather than naturally occurring ginsenosides, lead to inhibition of human cytochrome P450 enzymes. Toxicol Sci. 2006;91:356–364. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankawa U, Sung CK, Han BH, Akiyama T, Kawashima K. Radioimmunoassay for the determination of ginseng saponin, ginsenoside Rg1. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1982;30:1907–1910. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Fukuda N, Shoyama Y. Formation of monoclonal antibody against a major ginseng component, ginsenoside Rb1 and its characterization. Cytotechnology. 1999;29:115–120. doi: 10.1023/A:1008068718392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda N, Tanaka H, Shoyama Y. Formation of monoclonal antibody against a major ginseng component, ginsenoside Rg1 and its characterization. Chytotechnology. 2000;34:197–204. doi: 10.1023/A:1008162703957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morinaga O, Tanaka H, Shoyama Y. Detection and quantification of ginsenoside Re in ginseng samples by chromatographic immunostaining method using monoclonal antibody against ginsenoside Re. J Chromatogr B. 2006;830:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo EJ, Ha YW, Shin H, Son SH, Kim YS. Generation and characterization of monoclonal antibody to ginsenoside Rg3. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32:548–552. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karikura M, Miyase T, Tanizawa H, Takino Y. Studies on absorption, distribution, excretion and metabolism of ginseng saponins. VI. The decomposition products of ginsenoside Rb2 in the stomach of rats. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1991;39:400–404. doi: 10.1248/cpb.39.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa H, Sung JH, Matsumiya S, Uchiyama M. Main ginseng saponin metabolites formed by intestinal bacteria. Planta Med. 1996;62:453–457. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae EA, Choo MK, Park EK, Park SY, Shin HY, Kim DH. Metabolism of ginsenoside Re by human intestinal bacteria and its related antiollergic activity. Biol Pharm Bull. 2002;25:743–747. doi: 10.1248/bpb.25.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa H, Sung JH, Benno Y. Role of human intestinal Prevotella oris in hydrolyzing ginseng saponins. Planta Med. 1997;63:436–440. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akao T, Kida H, Kanaoka M, Hattori M, Kobashi K. Intestinal bacterial hydrolysis is required for appearance of compound K in rat plasma after oral administration of ginsenoside Rb1 from Panax ginseng. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1998;50:1155–1160. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1998.tb03327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi H, Kim DH, Ji GE. Transformation of ginsenoside Rb2 and Rc from Panax ginseng by food microorganisms. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:2102–2105. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie HT, Wang GJ, Chen M, Jiang XL, Li H, Lv H, Huang CR, Wang R, Roberts M. Uptake and metabolism of ginsenoside Rh2 and its aglycon protopanaxadiol by Caco-2 cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:383–386. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Fang XL. Difference in oral absorption of ginsenoside Rg1 between in vitro and in vivo models. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:499–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Sha X, Wu Y, Fang X. Oral absorption of ginsenoside Rb1 using in vitro and in vivo models. Planta Med. 2006;72:398–404. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-916211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J, Sun M, Guo J, Huang L, Wang S, Meng B, Ping Q. Active absorption of ginsenoside Rg1 in vitro and in vivo: the role of sodium-dependent glucose co-transporter 1. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2009;61:381–386. doi: 10.1211/jpp/61.03.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karikura M, Miyase T, Tanizawa H, Takino Y, Taniyama T, Hayashi T. Studies on absorption, distribution, excretion and metabolism of ginseng saponins. V. The decomposition products of ginsenoside Rb2 in the large intestine of rats. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1990;38:2859–2861. doi: 10.1248/cpb.38.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takino Y. Studies on pharmacodynamics of ginsenoside-Rg1, Rb1 and -Rb2 in rats. Yakugaku Zasshi. 1994;114:550–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu QF, Fand XL, Chen DF. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of ginsenoside Rb1 and Rg1 from Panax notoginseng in rats. J Ethnopharmcol. 2003;84:187–192. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(02)00317-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odani T, Tanizawa H, Takino Y. Studies on the absorption, distribution, excretion and metabolism of ginseng saponins. II. The absorption, distribution and excretion of ginsenoside Rg1 in the rat. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1983;31:292–298. doi: 10.1248/cpb.31.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odani T, Tanizawa H, Takino Y. Studies on the absorption, distribution, excretion and metabolism of ginseng saponins. III. The absorption, distribution and excretion of ginsenoside Rb1 in the rat. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1983;31:1059–1066. doi: 10.1248/cpb.31.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J, Sun M, Guo J, Huang L, Wang S, Meng B, Ping Q. Enhancement by adrenaline of ginsenoside Rg1 transport in Caco-2 cells and oral absorption in rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2009;61:347–352. doi: 10.1211/jpp/61.03.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J, Guo J, Huang L, Meng B, Ping Q. The use of lipid-based formulations to increase the oral bioavailability of Panax notoginseng saponins following a single oral gavage to rats. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2008;34:65–72. doi: 10.1080/03639040701508292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M, Fu S, Gao JQ, Fang XL. Evaluation of intestinal absorption of ginsenoside Rg1 incorporated in microemulison using parallel artificial membrane permeability assay. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32:1069–1074. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SW, Kwon HY, Chi DW, Shim JH, Park JD, Lee YH, Pyo S, Rhee DK. Reversal of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance by ginsenoside Rg3. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65:75–82. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(02)01446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon HY, Kim EH, Kim SW, Kim SN, Park JD, Rhee DK. Selective toxicity of ginsenoside Rg3 on multidrug resistant cells by membrane fluidity modulation. Arch Pharm Res. 2008;31:171–177. doi: 10.1007/s12272-001-1137-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salim KN, McEwen BS, Chao HM. Ginsenoside Rb1 regulates ChAT, NGF and trkA mRNA expression in the rat brain. Mol Brain Res. 1997;47:177–182. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(97)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Lee JH, Oh S, Rhim H, Lee SM, Nah SY. Effects of ginsenoside Rg2 on the 5-HT3A receptor-mediated ion current in Xenopus oocytes. Mol Cells. pp. 108–113. [PubMed]

- Kim HS, Hwang SL, Oh S. Ginsenoside Rc and Rg1 differentially modulate NMDA receptor subunit mRNA levels after intracerebroventricular infusion in rats. Neurochem Res. 2000;25:1149–1154. doi: 10.1023/A:1007634432095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Jung SY, Lee JH, Sala F, Criado M, Mulet J, Valor LM, Sala S, Engel AG, Nah SY. Effects of ginsenosides, active components of ginseng, on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;442:37–45. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(02)01508-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Chung E, Lee KY, Lee YH, Huh B, Lee SK. Ginsenoside-Rg1, one of the major active molecules from Panax ginseng, is a functional ligand of glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1997;133:135–140. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(97)00160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung KW, Cheng YK, Mak NK, Chan KKC, Fan TPD, Wong RNS. Signaling pathway of ginsenoside-Rg1 leading to nitric oxide production in endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:3211–3216. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung KW, Leung FP, Huang Y, Mak NK, Wong RNS. Non-genomic effects of ginsenoside-Re in endothelial cells via glucocorticoid receptor. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2423–2428. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Jin YR, Lim WC, Ji SM, Choi S, Jang S, Lee SK. A ginsenoside-Rh1, a component of ginseng saponin, activates estrogen receptor in human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;84:463–468. doi: 10.1016/S0960-0760(03)00067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato P, Christophe S, Mellon PL. Estrogenic activity of herbs commonly used as remedies for menopausal symptoms. Menopause. 2002;9:145–150. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200203000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Burdette JE, Xu H, Gu C, van Breemen RB, Bhat KPL, Booth N, Constantinou AI, Pezzuto JM, Fong HHS, Farnsworth NR, Bolton JL. Evaluation of estrogenic activity of plant extracts for the potential treatment of menopausal symptoms. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:2472–2479. doi: 10.1021/jf0014157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao QG, Chen WF, Xie JX, Wong MS. Ginsenoside Rg1 protects against 6-OHDA-induced neurotoxicity in neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cells via IGF-I receptor and estrogen receptor pathways. J Neurochem. 2009;109:1338–1347. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T, Bai CX, Kaihara A, Ozaki E, Kawano T, Nakaya Y, Awais M, Sato M, Umezawa Y, Kurokawa J. Ginsenoside Re, a main phytosterol of Panax ginseng, activates cardiac potassium channels via a nongenomic pathway of sex hormones. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1916–1924. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.028134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung KW, Leung FP, Mak NK, Tombran-Tink J, Huang Y, Wong RNS. Protopanaxadiol and protopanaxatriol bind to glucocorticoid and oestrogen receptors in endothelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:626–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]