Abstract

The eukaryotic transcription factor NF-κB regulates a wide range of host genes that control the inflammatory and immune responses, programmed cell death, cell proliferation and differentiation. The activation of NF-κB is tightly controlled both in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus. While the upstream cytoplasmic regulatory events for the activation of NF-κB are well studied, much less is known about the nuclear regulation of NF-κB. Emerging evidence suggests that NF-κB undergoes a variety of posttranslational modifications, and that these modifications play a key role in determining the duration and strength of NF-κB nuclear activity as well as its transcriptional output. Here we summarize the recent advances in our understanding of the posttranslational modifications of NF-κB, the interplay between the various modifications, and the physiological relevance of these modifications.

Keywords: NF-κB, posttranslational modifications, transcriptional activation, inflammatory response, cancer

1. Introduction

The eukaryotic transcription factor NF-κB/Rel family proteins regulate a wide range of host genes that govern the inflammatory and immune responses in mammals and play a critical role in controlling programmed cell death, cell proliferation and differentiation. In mammals, the NF-κB/Rel family consists of seven proteins, including RelA/p65, c-Rel, RelB, p100, p52, p105 and p50 [1; 2]. Each protein contains a Rel homology domain (RHD) within the N-terminus and can form homo- or heterodimers through the RHD [1; 2].

The prototypical NF-κB is a heterodimer of p50 and RelA. In unstimulated cells, NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm by its association with an inhibitor protein, IκBα [1; 2]. NF-κB is activated by a variety of stimuli, including various proinflammatory cytokines, T- and B-cell receptor signals, and viral and bacterial products. Stimulation of the cells by these agonists leads to the activation of an IκB kinase complex of IκB kinases 1 and 2 (IKK1 and 2, also known as IKKα and IKKβ, respectively) and the non-catalytic NEMO subunit [3]. Activated IKKs then phosphorylate IκBα at serines-32 and -36, inducing its rapid ubiquitination and its degradation in the 26S proteasome [4]. The free NF-κB heterodimer rapidly translocates to the nucleus where it binds to the κB enhancer and stimulates gene expression through the transcriptional activation domain (TAD) of RelA [5]. NF-κB activates hundreds of genes involved in different biological processes including inflammation, proliferation and cell survival.

Many factors have been discovered to contribute to the transcriptional activation of NF-κB target genes, including the binding of different homo- or heterodimers of NF-κB to the cognate κB sites, the recruitment of various basal transcriptional factors and coactivators to the promoters, and the modifications of the histone tails around the promoters of NF-κB target genes [6]. Recent studies indicate that posttranslational modifications of NF-κB, especially of the RelA subunit, play a critical role in fine-tuning the transcriptional activity of NF-κB, adding another important layer of complexity to the transcriptional regulation of NF-κB. In the present review, we will focus on the posttranslational modifications of the RelA subunit of NF-κB, the regulation of these modifications, and the functions of these modifications in the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response and cancer. Posttranslational modifications of other NF-κB members may be found in other recent reviews [6–8].

2. Posttranslational modifications of NF-κB

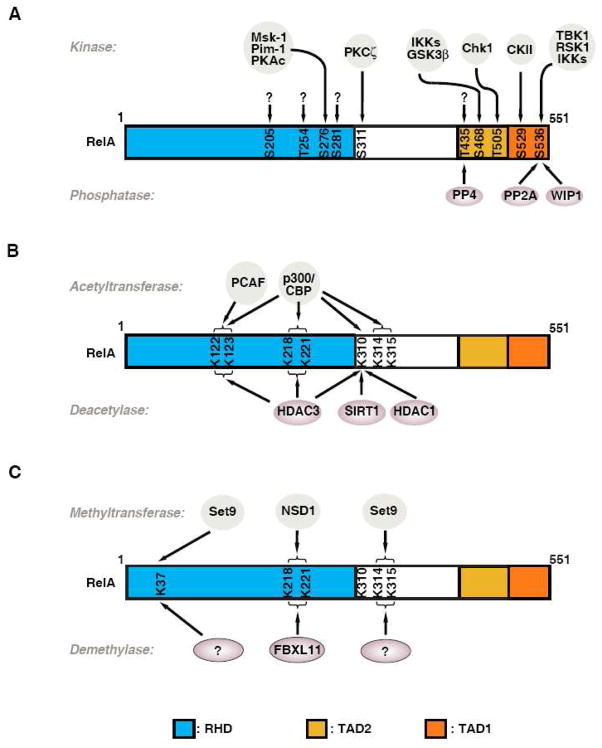

2.1 Phosphorylation of RelA

A role for phosphorylation of RelA in the regulation of NF-κB activity has long been suggested [9]. Accordingly, many kinases and phosphorylation sites including seven serines and three threonines have been identified (Fig. 1A). RelA can be phosphorylated both in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus in response to a variety of stimuli. Most of the phosphorylation sites are within the N-terminal RHD and the C-terminal transcriptional activation domains. Phosphorylation of these sites results in either increased or decreased levels of transcription, depending on the sites of phosphorylation, the target genes, and the stimuli.

Fig. 1.

Posttranslational modifications of RelA by phosphorylation, acetylation and methylation. (A) Regulation of RelA phosphorylation by various kinases and phosphatases. Schematic representation shows seven serine phosphorylation sites and three threonine phosphorylation sites identified in RelA. Most of the sites are located in the Rel homology domain (RHD) and the transactivation domains (TAD1 and TAD2). Several sites are phosphorylated by more than one kinase and some kinases phosphorylate numerous sites. The kinases for S205, S281, T254 and T435 are unknown right now. Three phosphatases have been shown to dephosphorylate RelA. (B) Reversible acetylation of RelA. RelA is acetylated by p300/CBP or PCAF at multiple lysines. Lysines 218, 221, 310, 314 and 315 are acetylated by p300/CBP, whereas lysines 122 and 123 are acetylated by both p300/CBP and PCAF. These acetylated sites are selectively deacetylated by HDAC1, HDAC3 or SIRT1, respectively. (C) Regulation of RelA by reversible lysine methylation. NSD1 monomethylates K218 and dimethylates K221; these methylated lysines are demethylated by FBXL11. Set9 monomethylates K37 and K314 and K315. Whether Set9-mediated methylation of K37, K314 and K315 is subject to demethylation is not known.

2.1.1 Phosphorylation of serine 276

Phosphorylation of serine (S) 276 within the RHD was first identified to be mediated by the catalytic subunit of protein kinase A (PKAc) which is activated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). LPS-induced degradation of IκBα releases the constitutively active PKAc from the constraints of IκBα [10]. Later on, several stimuli, including TNF-α- and TGF-β, were also shown to activate PKAc and induce PKAc-mediated phosphorylation of S276 [11; 12]. Phosphorylation of S276 in response to these various stimuli enhances the overall transcriptional activity of NF-κB. S276 is also targeted by mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase-1 (MSK1) in response to TNF-α, IL-1β, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and H. pylori infection [12–15]. Different from PKAc, MSK1 phosphorylates RelA in the nucleus [13]. Phosphorylation of S276 by MSK1 enhances the transcriptional activity of NF-κB and the NF-κB-dependent expression of cytokines including IL-6 and IL-8 [12–15].

The enhanced transcriptional activity of RelA via S276 phosphorylation likely reflects the phosphorylation-induced RelA conformational change, leading to the increased or decreased binding of RelA with NF-κB cofactors. For example, phosphorylation of S276 by PKAc has been shown to weaken the intramolecular interaction between the N- and C-terminal portions of RelA, which in turn allows the efficient binding of p300/CBP to the open RelA [16]. In another study, phosphorylation of S276 by PKAc has been shown to enhance the interaction between RelA and cyclin-dependent kinase 9/Cyclin T1 complexes [17]. Similarly, phosphorylation at S276 by MSK1 facilitates the recruitment of CBP to the promoters of NF-κB target genes [14]. Therefore, the phosphorylation-mediated conformational change appears to enhance the binding of RelA to its cofactors, and these cofactors might form a bridge between NF-κB and the components of the cellular transcriptional machinery. In contrast, the unphosphorylated RelA conformation might facilitate its association with co-repressors, leading to the decreased transcriptional activity of NF-κB. In a recent study with RelA “knock-in” mice expressing RelA-S276A, Dong et al demonstrate that the unphosphorylated form of RelA associates with HDAC3, which suppresses not only a subset of NF-κB target genes but also represses non-NF-κB-regulated genes through an epigenetic mechanism [18]. In addition to the phosphorylation-dependent recruitment of coactivators or disengagement of co-repressors, it is possible that phosphorylation of S276 regulates the function of NF-κB via other mechanisms. A recent report shows that phosphorylation of S276 by kinase Pim-1 in response to TNF-α enhances the transcriptional activation of NF-κB target genes by stabilizing RelA [19], but the detailed mechanism remains unclear.

2.1.2 Phosphorylation of serine 536

Another well-studied phosphorylation site of RelA is serine 536 within the TAD. S536 is targeted for phosphorylation under various conditions by different kinases including IKKs, ribosomal subunit kinase-1 (RSK1), and TANK binding kinase (TBK1) [20–24] with different functional consequences (Fig. 1A). The IKKs-mediated phosphorylation of S536 is induced by TNF-α, LPS, H. pylori and human T lymphotrophic virus-1 (HTLV1)-encoded TAX protein [20–22; 24; 25]. The enhanced transcriptional activity of NF-κB after phosphorylation of S536 might also result from the conformational change of RelA affecting RelA’s interaction with other proteins. Supporting this idea, phosphorylation of S536 by IKKs has been shown to increase RelA’s binding with p300 but decrease its binding with co-repressor SMRT (silencing mediator for retinoic acid receptor and thyroid hormone receptor) [26; 27]. In addition, RSK1- or TBK1-mediated phosphorylation of S536 lowers RelA’s affinity for IκBα and decreases IκBα-mediated nuclear export of NF-κB [22; 23]. Although it is well accepted that phosphorylation of S536 represents an active mark for canonical NF-κB activation, it has to be noted that phosphorylation of S536 could also be involved in non-canonical NF-κB activation which is independent of IκBα degradation. As such, the expression of genes regulated by this mechanism appears to be different with respect to those regulated by IκBα-mediated NF-κB canonical activation [22; 28].

2.1.3 Phosphorylation of serine 468

Although RelA phosphorylation is often associated with the enhanced transcriptional activation of NF-κB, phosphorylation at certain residues can result in decreased transcriptional activity of NF-κB. S468 is one of the residues whose phosphorylation negatively modulates transcriptional activation of NF-κB. S468 of RelA within the TAD can be phosphorylated by three different kinases including GSK3β, IKKβ and IKKε under unstimulated or stimulated conditions. S468 is constitutively phosphorylated by GSK3β without any stimuli, and this phosphorylation negatively regulates the basal NF-κB activity [29]. S468 is also inducibly phosphorylated by IKKβ or IKKε in response to TNF-α and IL-1β, and phosphorylation of S468 by these kinases moderately reduces the stimulated NF-κB activity by enhancing the binding of the COMMD1-containing E3 ligase complex for the degradation of NF-κB [30–32]. Surprisingly, phosphorylation of S468 by IKKε in T cells enhances the transcriptional activation of NF-κB in response to T cell co-stimulation [21]. These different outcomes suggest that phosphorylation of S468 regulates the transcriptional activity of NF-κB in a context-dependent manner, but the mechanism underlying this requires further investigation.

2.1.4 Phosphorylation of RelA at other residues

Other residues that are phosphorylated and have been implicated in NF-κB regulation include S205, S281, S311, S529, T254, T435 and T505 (Fig. 1A). Anrather et al found that S205 and S281 within the RHD were phosphorylated after LPS stimulation [33]. Phosphorylation of these serines by an unknown kinase(s) moderately regulates the transcriptional activity of some NF-κB target genes. S311 is inducibly phosphorylated by PKCζ in a TNF-α-dependent manner [34]. Similar to phosphorylation of S276 and S536, phosphorylation of S311 enhances the transcriptional activity of NF-κB by enhancing the recruitment of CBP to the promoter of IL-6 [34]. Phosphorylation of S529 by casein kinase 2 (CK2) has also been described to moderately enhance the transcriptional activity of NF-κB [35]. In contrast, phosphorylation of T435 by an unknown kinase negatively regulates the transcriptional activity of RelA [36; 37]. Tumor suppressor ARF-induced phosphorylation of T505 by Chk1 was also found to inhibit RelA transcriptional activity [38; 39]. Phosphorylation of these two threonine residues has been demonstrated to provide a docking site for the binding of HDAC1, thus inhibiting the transcriptional activation of NF-κB [37; 39].

2.1.5 Dephosphorylation of NF-κB by phosphatases

A role for phosphatases in the regulation of the transcriptional activation of NF-κB has also been described. Dephosphorylation of RelA might be an important step in re-establishing the normal responsiveness of NF-κB by terminating NF-κB signaling after stimulant removal or target gene expression [40; 41]. Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) interacts with RelA under unstimulated conditions and directly dephosphorylates RelA in vitro [40]. Using a systematic RNAi screen of phosphatases that modulate NF-κB activity, Li et al also identified PP2A as a RelA phosphatase, which specifically dephosphorylates S536 but not S276 in vitro [42]. Consistent with the positive regulatory role of phosphorylated S536, dephosphorylation of RelA by PP2A inhibits the transcription activity of NF-κB [42]. In a different study, Chew et al identified WIP1 as another S536 phosphatase [41]. Dephosphorylation at S536 reduces RelA’s interaction with p300 and hence transcription of NF-κB target genes [41]. Although both PP2A and WIP1 dephosphorylate S536, these S536 phosphatases do not cooperate and have non-redundant roles in vivo [41]. Interestingly, dephosphorylation of RelA at T435 by phosphatase 4 is involved in cisplatin-induced NF-κB activation, although the kinase responsible for the T435 phosphorylation is not clear [36]. It appears that, like phosphorylation, dephosphorylation of RelA by phosphatases regulates the functions of NF-κB in a context-dependent and signal-dependent manner.

2.2 Reversible acetylation of NF-κB

Acetylation is another important posttranslational modification of RelA that has been extensively studied over the years. Different from phosphorylation, acetylation mostly occurs in the nucleus, where most of the enzymes mediating this modification reside. These enzymes include histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases, which mediate the addition or removal of the acetyl group to and from lysine residues. Reversible acetylation of RelA regulates diverse functions of NF-κB, including DNA binding activity, transcriptional activity, and its ability to associate with IκBα, and plays important roles in the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response and cancer.

2.2.1 Acetylation of RelA

Seven acetylated lysines have been identified within RelA, including lysines 122, 123, 218, 221, 310, 314 and 315 (Fig. 1B). The majority of these lysines are acetylated by p300/CBP, but some lysines, like 122 and 123, can be acetylated by PCAF as well [43]. Acetylation of these different lysines modulates distinct functions of NF-κB. For example, acetylation at K221 enhances the DNA binding of NF-κB and, together with acetylation at K218, impairs its association with IκBα [44]. Acetylation of K310 is required for full transcriptional activity of NF-κB, but does not affect DNA binding or IκBα assembly. Whereas acetylation of K122 and K123 by p300/CBP or PCAF seems to negatively regulate NF-κB-mediated transcription by reducing RelA binding to the κB enhancer [43]. Interestingly, acetylation of RelA at K314 and K315 by p300 affects neither NF-κB shuttling, DNA binding, nor the induction of anti-apoptotic genes, but differentially regulates the expression of specific sets of NF-κB target genes in response to TNF-α stimulation [45; 46].

How does acetylation regulate different aspects of NF-κB? Acetylation of different lysines might utilize distinct mechanisms to regulate the functions of NF-κB. First, acetylation might change the conformation of RelA which would then allow for enhanced or reduced binding to its partner proteins. The reduced IκBα binding from the acetylated K221 might well attribute to its conformation change. In the crystal structure of RelA-p50-IκBα, K221 directly interacts with methionine 279 in the sixth ankyrin repeat of IκBα [47]. It is predicted that acetylation of K221 might change the conformation of RelA and interfere with the interface between RelA and IκBα. This reduced IκBα binding might also account for the acetylated K221-enhanced NF-κB DNA binding affinity, since IκBα is known to bind to promoter-bound NF-κB and remove it [2]. In addition to the conformational change, acetylation might create a docking site for the recruitment of some NF-κB transcription cofactors. Supporting this hypothesis, our recent studies demonstrate that acetylated K310 is specifically recognized by two bromodomains of Brd4, which recruits and activates CDK9 to phosphorylate RNA polymerase II for the transcription of a subset of NF-κB target genes [48]. Finally, acetylation might regulate the functions of NF-κB simply by neutralizing the positively charged lysine, which might explain how acetylation of K122 and K123 reduces DNA binding activity of NF-κB. In the crystal structure of the RelA/p50 heterodimer bound to a κB-enhancer, K122 and K123 are the only residues that contact the DNA in the minor grove [47]. It is likely that the reduced DNA binding activity from K122 and K123 acetylation results from the neutralization of these positively charged lysines which weaken their interaction with the negatively charged DNA. It is not clear how the acetylation of K314 and K315 activates a subset of NF-κB target genes. One possibility is that acetylation of these two lysines might prevent their methylation, a modification that has recently been shown to negatively regulate the function of NF-κB by inducing the degradation of RelA [49].

2.2.2 Deacetylation of NF-κB

Acetylation is a reversible event mediated by both histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) and the effect of HATs is opposed in the cells by HDACs. As such, several HDACs, including HDAC1, HDAC3 and SIRT1, have been found to specifically deacetylate RelA and regulate the functions of NF-κB. We first demonstrated that RelA was selectively deacetylated in vivo by HDAC3 [50]. Deacetylation of RelA by HDAC3 not only inhibits the transcriptional activity of NF-κB, but also promotes the binding of RelA with IκBα, likely through the deacetylation of K218 and K221, leading to the nuclear export of NF-κB [44; 50]. HDAC3-mediated deacetylation functions as an intramolecular switch for the IκBα-mediated termination of NF-κB signaling [50]. In contrast, HDAC3 has also been reported to deacetylate K122 and K123 and enhance the DNA binding activity of NF-κB [43]. In addition to HDAC3, two other HDACs, including HDAC1 and SIRT1, have been demonstrated to deacetylate K310. Deacetylation of K310 by HDAC1 is responsible for the decreased transcriptional activity of NF-κB by the breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 (BRMS1) [51], whereas SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of K310 inhibits the transcriptional activity of NF-κB and sensitizes cells to TNF-α-induced apoptosis [52]. Inhibiting the activity of SIRT1 with LPS, acetaldehyde or acetate was associated with a marked increase in the acetylation of K310 and the transcriptional activity of NF-κB [53].

2.3 Methylation

In addition to phosphorylation and acetylation, lysine methylation has recently emerged as another important modification for the regulation of nuclear NF-κB function. The functional consequence of methylation depends on both position and state of the methylation site, since lysine can be mono-, di-, or tri-methylated. Several methyltransferases have been identified to methylate RelA and regulate distinct functions of NF-κB.

2.3.1 Set9-mediated methylation of RelA

Set9 (also called Set7 or KMT7), a SET (suppressor of variegation-enhancer of zeste-trithorax) domain histone lysine methyltransferase (HKMT), was originally identified to mediate the lysine methylation of histone H3. Later, many non-histone proteins including p53, estrogen receptors and TAF10, were also found to be targets of Set9 [54]. Our recent studies identified RelA as another target of Set9 [49]. Set9 specifically monomethylates RelA at K314 and K315 in vitro and in vivo [49]. TNF-α- or LPS-induced methylation of RelA by Set9 negatively regulates the function of NF-κB by inducing the ubiquitination and degradation of promoter-bound RelA. Interestingly, in a different study, Ea et al showed that Set9 is able to methylate a different lysine residue, K37 [55]. In contrast to the negative regulation of NF-κB by Set9-mediated methylation of K314 and K315, methylation of K37 appears to be important for the activation of a subset of NF-κB target genes by stabilizing the binding of NF-κB to its enhancers [55]. Currently, it is not clear how Set9 selectively methylates different lysines of RelA and differentially controls the function of NF-κB. One possibility is that Set9-mediated methylation of RelA and regulation of NF-κB depends on the cellular context and the specific promoters of NF-κB target genes. It is also possible that Set9 sequentially methylates different lysines during the course of NF-κB activation which exert various effects. Further experiments will be needed to differentiate among these possibilities.

2.3.2 Reversible methylation of RelA by NSD1 and FBXL11

Nuclear receptor-binding SET domain-containing protein1 (NSD1), a histone H3K36 methyltransferase, has recently been found to methylate K218 and K221 [56], which were originally identified to be acetylated by p300/CBP. NSD1 monomethylates K218 and dimethylates K221. Methylation of RelA by NSD1 enhances the transcriptional activity of NF-κB and the expression of NF-κB target genes. Similar to phosphorylation and acetylation, studies in the past several years demonstrate that methylation is also a reversible event with the identification of many histone demethylases [57; 58]. Consistent with the notion that lysine methylation is a reversible event mediated by methyltransferases and demethylases, methylated K218 and K221 is demethylated by F-box and leucine-rich repeat protein 11 (FBXL11) [56], an H3K36 demethylase also known to demethylate NSD1-mediated lysine methylation [59]. Demethylation of RelA by FBXL11 negatively regulates the transcriptional activity of NF-κB and decreases cell proliferation and colony formation of HT29 cancer cells [56; 60]. While K218 and K221 are reversibly methylated by NSD1 and FBXL11, the respective demethylases for the Set9-mediated methylation of K37, K314 and K315 are not currently known. Identification of the specific demethylases for each lysine would provide new insights into the regulation of NF-κB by reversible methylation.

As mentioned above, lysine methylation has emerged as another important modification for the regulation of NF-κB, though it remains unclear whether RelA is also modified by arginine methylation. Several arginine methyltransferases, including PRMT1 [61], PRMT2 [61] and PRMT4 (CARM1) [62], are found to be important NF-κB cofactors for NF-κB-dependent gene transcription. Therefore, whether these enzymes could also directly target RelA for arginine methylation and NF-κB regulation remains an interesting question.

2.4 Ubiquitination

The covalent conjugation of ubiquitin to cellular proteins regulates a broad range of eukaryotic cell functions, frequently by mediating the proteasome-dependent degradation of various master regulatory proteins [63]. Ubiquitination and degradation of NF-κB subunits has been recently established as a novel mechanism controlling NF-κB strength and duration [64]. Succani et al. demonstrated that after activation, RelA is ubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome in the nucleus and in a DNA binding-dependent manner. When the proteasome activity is blocked, both the promoter binding of NF-κB and the transcription mediated by NF-κB are prolonged [65]. This observation demonstrates that in addition to the resynthesis of IκBα, ubiquitination and degradation of NF-κB serves as another mechanism to terminate the NF-κB response [64]. Several E3 ligases have been identified to be involved in RelA ubiquitination.

2.4.1 Ubiquitination mediated by SOCS1

By protein complex purification and mass spectrometry, SOCS1 (suppressor of cytokine signaling 1) was identified as an E3 ligase for the RelA subunit. SOCS1 binds to and ubiquitinates RelA in a LPS-dependant manner [66]. Studies of the regulation of SOCS1-containing elongin-cullin-SOCS E3 ligase complex, in which SOCS1 functions as a substrate receptor, identified two regulators of SOCS1 for the ubiquitination of RelA: COMMD1 (also called MURR1) and GCN5. COMMD1, a ubiquitously expressed inhibitor of NF-κB [67; 68], promotes ubiquitination and degradation of nuclear RelA by binding to both SOCS1 and RelA and stabilizing SOCS1-RelA interaction [32; 69]. As a COMMD1-associated factor, GCN5 also suppresses NF-κB activation by enhancing the ubiquitination and degradation of RelA independently of its histone acetyltransferase activity [31].

Similar to the function of SOCS1 in mammalian cells, murid herpesvirus-4 (MuHV-4) protein ORF73 targets nuclear RelA for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [70]. ORF73 harbors a SOCS box-like motif that mediates the assembly of elonginC/cullin5/ORF73 complex. Therefore, ORF73 mimics the host SOCS1 E3 ligase in inhibiting NF-κB activity and plays a critical role in the establishment of a persistent gamma herpes virus infection [70]. These findings underscore the physiological importance of ubiquitination and degradation of RelA in the NF-κB signaling pathway.

2.4.2 Ubiquitination mediated by PDLIM2

Despite increasing evidence showing that SOCS1 is an E3 for nuclear NF-κB, the fact that SOCS1 mainly resides in the cytoplasm proves inconsistent [64; 71]. In searching for a nuclear E3 ligase, Tanaka et al demonstrated that PDLIM2, a nuclear LIM domain-containing protein which has previously been shown to have polyubiquitin ligase activity, also contributes to the turnover of nuclear NF-κB [71]. PDLIM2 promotes the translocation of NF-κB to an insoluble compartment that consists of promyelocytic leukemia (PML) nuclear bodies, where RelA is polyubiquitinated by PDLIM2 and degraded by the proteasome [71]. PDLIM2 deficiency results in large amounts of nuclear RelA, defective RelA ubiquitination and increased production of proinflammatory cytokines in response to LPS [71]. However, PDLIM2-mediated ubiquitination of RelA is cell-type specific and is mostly restricted to the myeloid cells, indicating that other E3 ligases targeting nuclear RelA might exist.

2.4.3 Ubiquitination mediated by unknown E3 ligases

Consistent with the idea that other E3 ligases might also target NF-κB, studies using IkkαAA/AA mice, which express an inactive variant of IKKα (AA), revealed that IKKα limits NF-κB activation in macrophages in response to LPS by promoting turnover of promoter-bound NF-κB [72]. The observed connection between the IKKα-dependent S536 phosphorylation of RelA and the abrogation of LPS-induced turnover of the RelA S536A mutant suggests that S536 phosphorylation probably induces protein degradation in the nucleus by an unknown E3 ligase [72]. Additionally, our recent studies demonstrate that lysine methyltransferase Set9 targets RelA for methylation which in turn induces ubiquitination and degradation of promoter-bound NF-κB [49]. Methylated RelA might recruit an E3 ligase for its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation. However, the identity of the E3 ligase remains to be determined. Our preliminary data indicate that neither SOCS1 nor PDLIM2 seem to be the E3 ligase for methylated ReA. The methylated RelA E3 ligase might contain one of the methyl-lysine binding domains, such as chromodomain, Tudor, PHD domain or WD40 repeats [73], since the binding of the E3 ligase to promoter-bound RelA appears to be methylation-dependent [54].

3. Interplay between various posttranslational modifications

The interplay between different posttranslational modifications has been identified for histone and non-histone proteins, with one modification either enhancing or inhibiting another modification [74; 75]. The cross talk between modifications together with the distinct combinations of covalent modifications form the basis of the “histone code” and probably the “protein code” hypothesis [76; 77]. RelA undergoes numerous posttranslational modifications, and there are many different interplays between these modifications, reflecting a defined and comprehensive regulation for the transcriptional activation of NF-κB.

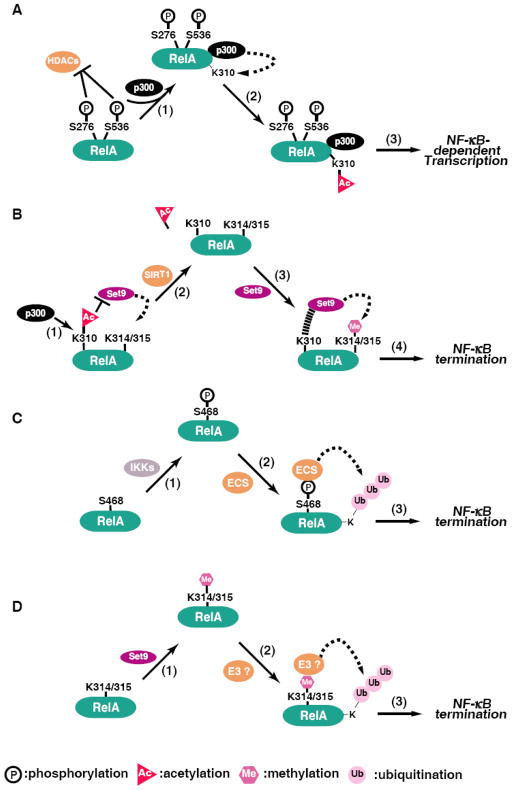

3.1 Phosphorylation enhances acetylation

Phosphorylation of RelA at several serines has long been shown to enhance the binding of p300/CBP, which mediates the acetylation of RelA, suggesting a possible link between phosphorylation and acetylation. In fact, cross-reactions between phosphorylation and acetylation for the transcriptional activation of NF-κB have been reported. Our earlier studies demonstrated that prior phosphorylation of RelA at S276 and S536 stimulates subsequent acetylation of K310 [26], thus enhancing the overall transcriptional activity of NF-κB (Fig. 2A). In a similar study, Hoberg et al show that in addition to the recruitment of p300/CBP, phosphorylation of S536 of RelA by IKKα displaces the SMRT-HDAC3 complex, allowing for the acetylation of RelA and the transcriptional activation of NF-κB [27]. Therefore, the effect of RelA phosphorylation might partially attribute to the subsequent acetylation of RelA.

Fig. 2.

Interplays between various posttranslational modifications. Schematic models for the interplays between different modifications. (A) Phosphorylation enhances the acetylation of RelA. Stimulus-coupled phosphorylation of S276 or S536 leads to more effective recruitment of p300 and displacement of HDACs (1), which in turn mediates the acetylation of K310 (2). Phosphorylated and acetylated forms of RelA can transcribe NF-κB-dependent genes (3). (B) Acetylation of K310 inhibits RelA methylation at K314 and K315. p300-mediated acetylation of K310 inhibits the binding of Set9 to RelA, thereby impairing the Set9-mediated methylation of K314 and K315 (1). Deacetylation of RelA by SIRT1 (2) facilitates the recruitment of Set9 to RelA and consequently leads to the methylation of K314 and K315 (3) and the termination of NF-κB activation (4). (C) Phosphorylation of S468 stimulates the ubiquitination of RelA. IKKs-mediated phosphorylation of S468 (1) facilitates the binding of the COMMD1-containing ECS E3 ligase complex for the ubiquitination (2) and subsequent degradation and termination of NF-κB (3). (D) Methylation of RelA triggers the ubiquitination and degradation of NF-κB. Set9-mediated methylation of K314 and K315 (1) might create a docking site for the recruitment of an unknown E3 ligase for the ubiquitination (2) and subsequent degradation and termination of NF-κB (3).

3.2 Interplay between acetylation and methylation

An interplay also exists for the acetylation of K310 and the methylation of the nearby K314 and K315, two modifications with opposite effects on the transcriptional activation of NF-κB. Our recent studies show that acetylation of K310 inhibits the Set9-mediated methylation of K314 and K315, but not vice versa (Fig. 2B). Enhancing the acetylation of K310 impairs the methylation and decreases methylation-induced ubiquitination, therefore prolonging the stability of chromatin-associated RelA and enhancing the transcriptional activity of NF-κB [78]. Acetylation of K310 likely interferes with the binding of Set9 to RelA by neutralizing the positive charge of K310 which is essential for its recognition by a negatively charged “exosite” within the SET domain of Set9 [78]. This study provides another example of the interplay between various posttranslational modifications and further supports the “NF-κB code” hypothesis [6].

3.3 Interplay between other modifications

Interplays between other modifications of RelA might also exist. For example, RelA phosphorylation has been shown to regulate the ubiquitination of RelA[31; 66]. It is likely that the modified serine serves as a mark for the recruitment or displacement of an E3 ligase or a component of an E3 ligase complex for the ubiquitination of RelA. Supporting this, phosphorylation of S468 has been shown to promote the ubiquitination of RelA through recruitment of an E3 ligase complex containing COMMD1, Cul2 and GCN5 [Fig. 2C and ref. 31]. However, a recent study also demonstrates a phosphorylated S468-independent binding of COMMD1 to ubiquitinate RelA in response to aspirin and stress [79]. Conversely, TNF-α-induced phosphorylation of RelA at T254 seems to prevent the binding of SOCS1 E3 ligase by a RelA conformational change mediated by the peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase Pin1 [66].

A cross-talk between different modifications at a single lysine might also exist for RelA, since several lysines, including 218, 221, 314 and 315, are found to be both acetylated and methylated, and these modifications affect the transcriptional activation of NF-κB in different ways. However, it is not clear how these different modifications compete with each other and what triggers the switch of these modifications within the cells.

4. Physiological relevance of posttranslational modifications

Although many of the above mentioned studies using biochemical and molecular approaches have demonstrated that various posttranslational modifications of RelA regulate distinct biological functions, especially the transcriptional activation of NF-κB, the physiological significance of these modifications is not well understood and is still being uncovered. Nevertheless, a growing number of studies have linked various posttranslational modifications to a variety of disease conditions, especially inflammatory diseases and cancer.

4.1 NF-κB phosphorylation in the inflammatory response and cancer

As implicated by its induction by LPS, phosphorylation of RelA has long been associated with bacteria-mediated inflammation. In fact, phosphorylation of RelA on S276 or S536 is important for polymicrobial infection-induced lung inflammation [80]. A synergistic induction of inflammation by LPS and fMLP is also linked to phosphorylation of both S276 and S536 [81]. Viruses also stimulate the phosphorylation of RelA. For example, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-induced airway innate inflammation is partially due to the MSK1-mediated phosphorylation of S276 [82]. On the other hand, inhibition of RelA phosphorylation has also been demonstrated to suppress NF-κB-mediated inflammation. For example, blocking the activity of MSK1 and the MSK1-dependent phosphorylation of S276 decreases the expression of SCF (stem cell factor), whose expression is often up-regulated in inflammatory conditions [14]. Licorice extract, licochalcone A, exerts its anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting LPS-induced phosphorylation of S276 [83]. Furthermore, inhibiting the phosphorylation of S276 and S536 suppresses H. influenzae and S. pneumonia-induced lung inflammation [80].

The role of NF-κB signaling in the initiation and progression of cancer has been well documented [84]. Recently, many studies also suggest a role for phosphorylated RelA in these processes. For example, phosphorylation of S276 by PKAc contributes to the malignant phenotype of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) [85]. Additionally, Joo et al show that NF-κB-dependent transcriptional activation and the induction of inflammatory genes in lung carcinoma cells by farnesol involves S276 phosphorylation via the MEK-MSK1 signaling pathway [86]. Phosphorylation of S536 has also been linked to a variety of cancers. The levels of phosphorylated S536 are found to associate highly with the Bcl-10 protein in peripheral T-cell lymphomas and are associated with clinical outcome [87]. CD7/CD56-positive acute myeloid leukemias are characterized by constitutively phosphorylated S536 [88]. Furthermore, IKK1-mediated constitutive phosphorylation of S536 is responsible for the proliferation of certain cancer cells [24].

Consistent with its role in cancer initiation and progression, inhibition of RelA phosphorylation is being recognized as a potential approach to inhibit tumorigenesis. Manna et al show that the anti-tumor compound P(3)-25 (5-(4-methoxyarylimino)-2-N-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-3-oxo-1,2,4-thiadiazolidine) exerts its antitumorigenic activity by decreasing phosphorylation of S276 and S536 by inhibiting the upstream kinases, and it potentiates apoptosis mediated by other chemotherapeutic agents [89]. In addition, tumor suppressor LZAP selectively inhibits NF-κB and sensitizes cells to TNF-α-induced cell death in HNSCCs by impairing the phosphorylation of S536 and enhancing RelA’s association with HDAC1, 2 and 3 [90]. These studies suggest that modulating the levels of RelA phosphorylation might be an important strategy for the future development of potential anti-cancer drugs.

4.2 Acetylation of RelA in the inflammatory response and cancer

Acetylation of RelA can be detected under many physiological and disease conditions and has been shown to be involved in the NF-κB-dependent inflammatory response. For example, high levels of oxidative stress in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) increase NF-κB acetylation and the expression of inflammatory genes [91]. Cigarette smoke can also enhance the acetylation of RelA and increase levels of proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages as well as in rat lungs by disrupting the interaction between SIRT1 and RelA [92].

Activation of NF-κB by different pathogens is often associated with hyperacetylation of NF-κB. Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) induces the acetylation of RelA, and this acetylation is essential for NTHi-induced NF-κB activation and inflammation [11; 93]. Acetylation of RelA is also involved in the regulation of adaptive immunity by dendritic cells (DCs) in response to bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens [94]. Pathogens including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. leprae, Candida albicans, measles virus, and human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV), trigger DC-SIGN and induce acetylation of RelA, resulting in both prolonged and increased IL-10 transcription to enhance the anti-inflammatory cytokine response [94]. An essential role for acetylation of K310 in HIV Tat-induced T cell hyperactivation has been reported recently. Kwon et al show that Tat directly associates with SIRT1 and blocks SIRT1’s ability to deacetylate K310 of RelA [95]. As a consequence, the transcriptional activity of NF-κB is significantly potentiated, which further triggers the immune activation involving T cell hyperactivation, the increased viral replication, and the deletion of CD4+ T cells [95].

Hyperacetylated RelA has been found in many cancer cells treated with HDAC inhibitors, and acetylation might account for the constitutively active NF-κB in cancer cells [96; 97]. Lee at al recently demonstrates that the frequently constitutively activated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) maintains the NF-κB activity and prolongs NF-κB nuclear retention through p300-mediated RelA acetylation in tumors. Stat3-mediated maintenance of NF-κB activity occurs in both cancer cells and tumor-associated hematopoietic cells. Both murine and human cancers display highly acetylated RelA, which is associated with Stat3 activity. Stat3-induced RelA acetylation is thus central to both the transformed and nontransformed elements in tumors [97].

Inhibiting the acetylation of RelA might prevent tumor cell transformation and induce tumor cell apoptosis. Choi et al showed that low dose epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG), a histone acetyltransferase inhibitor, completely blocks Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection-induced expression of cytokines and EBV-induced B lymphocyte transformation via suppression of RelA acetylation [98]. Another histone acetyltransferase inhibitor, anacardic acid (6-nonadecyl salicylic acid), has also been showed to suppress NF-κB-dependent cell survival, proliferation, invasion and inflammation partially by inhibiting p300-mediated acetylation of RelA [99]. Therefore, selectively inhibiting the acetylation of RelA might have therapeutic potential against cancer.

5. Conclusions and future prospective

In the last several years, increasing numbers of studies demonstrate that posttranslational modifications of RelA in response to different stimuli differentially regulate the functions of NF-κB. In addition to fine-tuning the transcriptional activity of NF-κB, these various posttranslational modifications of RelA also contribute to NF-κB target gene specificity [6], adding another level of complexity to the regulation of NF-κB transcriptional activation.

Posttranslational modifications of histone tails can occur sequentially or in combination to form a “histone code” that is read by the binding or divestment of specific cofactors, which combine to shape the ultimate transcriptional response [77; 100]. Similar to histones, the RelA subunit of NF-κB is also subject to a variety of posttranslational modifications, including phosphorylation, acetylation and ubiquitination [6; 64]. One of the important features of the “histone code” is that one modification can regulate another modification. As described above, various posttranslational modifications of RelA also regulate each other (Fig. 2). Therefore, by analogy to the histone code, a “NF-κB code” may also exist. Modifications of RelA at specific sites could, in fact, dictate specific biological responses, reflecting the gain or loss of selective cofactors whose association with RelA is regulated by its state of modifications. Additionally, the sequential modifications of RelA might help determine the temporal and spatial patterns of NF-κB activation and dictate the strength and duration of nuclear NF-κB activity.

Although significant progress has been made regarding the regulation of NF-κB by posttranslational modifications, it is important to note that regulation of NF-κB by posttranslational modifications is complex and likely occurs in a promoter-specific and stimulus-specific manner. Our understanding of these dynamic modifications might still be at an early stage due to the lack of appropriate approaches to monitor modifications of the endogenous proteins on a specific promoter. Future study should focus on investigating how a specific modification regulates a subset of NF-κB target genes to determine specificity, how these different modifications coordinate with the modifications on the histone proteins to tightly control the transcriptional activation of NF-κB under physiological and disease conditions, and how these modifications regulate the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response and anti-apoptotic function in vivo. Using proteomic approaches including developing site- and modification-specific antibodies and employing mass spectrometry techniques would allow us to better understand the regulation of these dynamic modifications in vivo and under more physiological conditions. Furthermore, genetic approaches, such as generating various modification-deficient RelA knock-in animals, would absolutely provide new insights in understanding the physiological functions of these modifications.

NF-κB has always been a target for drug discovery due to its important role in many inflammatory diseases and cancers, and a better understanding of the regulation and functions of these modifications would allow identification of drugs that directly target modified NF-κB with fewer side effects. At the same time, since NF-κB is constitutively activated in many cancers and inflammatory diseases, and NF-κB is hypermodified in some of these conditions, it would be of great interest to see whether any of these modifications might be used as a biomarker for the detection of specific inflammatory diseases or cancer.

Acknowledgments

Due to space constraints, we were not able to cite all the important original work in this field, and apologize to those authors whose work we did not cite. This work is supported by Indirect Cost Recovery provided by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and by NIH grant DK-085158 to LF Chen.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Baldwin AS., Jr The NF-kappa B and I kappa B proteins: new discoveries and insights. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:649–683. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghosh S, May MJ, Kopp EB. NF-kappa B and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:225–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karin M. How NF-kappaB is activated: the role of the IkappaB kinase (IKK) complex. Oncogene. 1999;18:6867–6874. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-[kappa]B activity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl):S81–S96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen LF, Greene WC. Shaping the nuclear action of NF-kappaB. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrm1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neumann M, Naumann M. Beyond IkappaBs: alternative regulation of NF-kappaB activity. FASEB J. 2007;21:2642–2654. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7615rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perkins ND. Post-translational modifications regulating the activity and function of the nuclear factor kappa B pathway. Oncogene. 2006;25:6717–6730. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D. NF-kappa B: ten years after. Cell. 1996;87:13–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong H, SuYang H, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Ghosh S. The transcriptional activity of NF-kappaB is regulated by the IkappaB-associated PKAc subunit through a cyclic AMP-independent mechanism. Cell. 1997;89:413–424. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishinaga H, Jono H, Lim JH, Kweon SM, Xu H, Ha UH, Xu H, Koga T, Yan C, Feng XH, Chen LF, Li JD. TGF-beta induces p65 acetylation to enhance bacteria-induced NF-kappaB activation. EMBO J. 2007;26:1150–1162. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jamaluddin M, Wang S, Boldogh I, Tian B, Brasier AR. TNF-alpha-induced NF-kappaB/RelA Ser(276) phosphorylation and enhanceosome formation is mediated by an ROS-dependent PKAc pathway. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1419–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vermeulen L, De WG, Van DP, Vanden BW, Haegeman G. Transcriptional activation of the NF-kappaB p65 subunit by mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase-1 (MSK1) EMBO J. 2003;22:1313–1324. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reber L, Vermeulen L, Haegeman G, Frossard N. Ser276 phosphorylation of NF-kB p65 by MSK1 controls SCF expression in inflammation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pathak SK, Basu S, Bhattacharyya A, Pathak S, Banerjee A, Basu J, Kundu M. TLR4-dependent NF-kappaB activation and mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1-triggered phosphorylation events are central to Helicobacter pylori peptidyl prolyl cis-, trans-isomerase (HP0175)-mediated induction of IL-6 release from macrophages. J Immunol. 2006;177:7950–7958. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong H, Voll RE, Ghosh S. Phosphorylation of NF-kappa B p65 by PKA stimulates transcriptional activity by promoting a novel bivalent interaction with the coactivator CBP/p300. Mol Cell. 1998;1:661–671. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nowak DE, Tian B, Jamaluddin M, Boldogh I, Vergara LA, Choudhary S, Brasier AR. RelA Ser276 phosphorylation is required for activation of a subset of NF-kappaB-dependent genes by recruiting cyclin-dependent kinase 9/cyclin T1 complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:3623–3638. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01152-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong J, Jimi E, Zhong H, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Repression of gene expression by unphosphorylated NF-kappaB p65 through epigenetic mechanisms. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1159–1173. doi: 10.1101/gad.1657408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nihira K, Ando Y, Yamaguchi T, Kagami Y, Miki Y, Yoshida K. Pim-1 controls NF-kappaB signalling by stabilizing RelA/p65. Cell Death Differ. 2009 doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakurai H, Chiba H, Miyoshi H, Sugita T, Toriumi W. IkappaB kinases phosphorylate NF-kappaB p65 subunit on serine 536 in the transactivation domain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30353–30356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattioli I, Geng H, Sebald A, Hodel M, Bucher C, Kracht M, Schmitz ML. Inducible phosphorylation of NF-kappa B p65 at serine 468 by T cell costimulation is mediated by IKK epsilon. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6175–6183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buss H, Dorrie A, Schmitz ML, Hoffmann E, Resch K, Kracht M. Constitutive and interleukin-1-inducible phosphorylation of p65 NF-{kappa}B at serine 536 is mediated by multiple protein kinases including I{kappa}B kinase (IKK)-{alpha}, IKK{beta}, IKK{epsilon}, TRAF family member-associated (TANK)-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), and an unknown kinase and couples p65 to TATA-binding protein-associated factor II31-mediated interleukin-8 transcription. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55633–55643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409825200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bohuslav J, Chen LF, Kwon H, Mu Y, Greene WC. p53 induces NF-kappaB activation by an IkappaB kinase-independent mechanism involving phosphorylation of p65 by ribosomal S6 kinase 1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:26115–26125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adli M, Baldwin AS. IKK-i/IKKepsilon controls constitutive, cancer cell-associated NF-kappaB activity via regulation of Ser-536 p65/RelA phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26976–26984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603133200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamb A, Yang XD, Tsang YH, Li JD, Higashi H, Hatakeyama M, Peek RM, Blanke SR, Chen LF. Helicobacter pylori CagA activates NF-kappaB by targeting TAK1 for TRAF6-mediated Lys 63 ubiquitination. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:1242–1249. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen LF, Williams SA, Mu Y, Nakano H, Duerr JM, Buckbinder L, Greene WC. NF-kappaB RelA phosphorylation regulates RelA acetylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7966–7975. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.7966-7975.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoberg JE, Popko AE, Ramsey CS, Mayo MW. IkappaB kinase alpha-mediated derepression of SMRT potentiates acetylation of RelA/p65 by p300. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:457–471. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.2.457-471.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sasaki CY, Barberi TJ, Ghosh P, Longo DL. Phosphorylation of RelA/p65 on serine 536 defines an I{kappa}B{alpha}-independent NF-{kappa}B pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:34538–34547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504943200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buss H, Dorrie A, Schmitz ML, Frank R, Livingstone M, Resch K, Kracht M. Phosphorylation of serine 468 by GSK-3beta negatively regulates basal p65 NF-kappaB activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49571–49574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400442200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwabe RF, Sakurai H. IKKbeta phosphorylates p65 at S468 in transactivaton domain 2. FASEB J. 2005;19:1758–1760. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3736fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mao X, Gluck N, Li D, Maine GN, Li H, Zaidi IW, Repaka A, Mayo MW, Burstein E. GCN5 is a required cofactor for a ubiquitin ligase that targets NF-kappaB/RelA. Genes Dev. 2009;23:849–861. doi: 10.1101/gad.1748409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geng H, Wittwer T, ttrich-Breiholz O, Kracht M, Schmitz ML. Phosphorylation of NF-kappaB p65 at Ser468 controls its COMMD1-dependent ubiquitination and target gene-specific proteasomal elimination. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:381–386. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anrather J, Racchumi G, Iadecola C. cis-acting, element-specific transcriptional activity of differentially phosphorylated nuclear factor-kappa B. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:244–252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409344200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duran A, az-Meco MT, Moscat J. Essential role of RelA Ser311 phosphorylation by zetaPKC in NF-kappaB transcriptional activation. EMBO J. 2003;22:3910–3918. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang D, Westerheide SD, Hanson JL, Baldwin AS., Jr Tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced phosphorylation of RelA/p65 on Ser529 is controlled by casein kinase II. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32592–32597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001358200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeh PY, Yeh KH, Chuang SE, Song YC, Cheng AL. Suppression of MEK/ERK signaling pathway enhances cisplatin-induced NF-kappaB activation by protein phosphatase 4-mediated NF-kappaB p65 Thr dephosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:26143–26148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Shea JM, Perkins ND. Thr-435 phosphorylation regulates RelA (p65) NF-kappaB subunit transactivation. Biochem J. 2009 doi: 10.1042/BJ20091630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campbell KJ, Witty JM, Rocha S, Perkins ND. Cisplatin mimics ARF tumor suppressor regulation of RelA (p65) nuclear factor-kappaB transactivation. Cancer Res. 2006;66:929–935. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rocha S, Garrett MD, Campbell KJ, Schumm K, Perkins ND. Regulation of NF-kappaB and p53 through activation of ATR and Chk1 by the ARF tumour suppressor. EMBO J. 2005;24:1157–1169. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang J, Fan GH, Wadzinski BE, Sakurai H, Richmond A. Protein phosphatase 2A interacts with and directly dephosphorylates RelA. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47828–47833. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106103200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chew J, Biswas S, Shreeram S, Humaidi M, Wong ET, Dhillion MK, Teo H, Hazra A, Fang CC, Lopez-Collazo E, Bulavin DV, Tergaonkar V. WIP1 phosphatase is a negative regulator of NF-kappaB signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:659–666. doi: 10.1038/ncb1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li S, Wang L, Berman MA, Zhang Y, Dorf ME. RNAi screen in mouse astrocytes identifies phosphatases that regulate NF-kappaB signaling. Mol Cell. 2006;24:497–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kiernan R, Bres V, Ng RW, Coudart MP, El MS, Sardet C, Jin DY, Emiliani S, Benkirane M. Post-activation turn-off of NF-kappa B-dependent transcription is regulated by acetylation of p65. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2758–2766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen LF, Mu Y, Greene WC. Acetylation of RelA at discrete sites regulates distinct nuclear functions of NF-kappaB. EMBO J. 2002;21:6539–6548. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rothgiesser KM, Fey M, Hottiger MO. Acetylation of p65 at lysine 314 is important for late NF-k(kappa)B-dependent gene expression BMC. Genomics. 2010;11:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buerki C, Rothgiesser KM, Valovka T, Owen HR, Rehrauer H, Fey M, Lane WS, Hottiger MO. Functional relevance of novel p300-mediated lysine 314 and 315 acetylation of RelA/p65. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:1665–1680. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen FE, Huang DB, Chen YQ, Ghosh G. Crystal structure of p50/p65 heterodimer of transcription factor NF-kappaB bound to DNA. Nature. 1998;391:410–413. doi: 10.1038/34956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang B, Yang XD, Zhou MM, Ozato K, Chen LF. Brd4 coactivates transcriptional activation of NF-kappaB via specific binding to acetylated. RelA Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1375–1387. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01365-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang XD, Huang B, Li M, Lamb A, Kelleher NL, Chen LF. Negative regulation of NF-kappaB action by Set9-mediated lysine methylation of the RelA subunit. EMBO J. 2009;28:1055–1066. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen L, Fischle W, Verdin E, Greene WC. Duration of nuclear NF-kappaB action regulated by reversible acetylation. Science. 2001;293:1653–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.1062374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu Y, Smith PW, Jones DR. Breast cancer metastasis suppressor 1 functions as a corepressor by enhancing histone deacetylase 1-mediated deacetylation of RelA/p65 and promoting apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8683–8696. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00940-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yeung F, Hoberg JE, Ramsey CS, Keller MD, Jones DR, Frye RA, Mayo MW. Modulation of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J. 2004;23:2369–2380. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shen Z, Ajmo JM, Rogers CQ, Liang X, Le L, Murr MM, Peng Y, You M. Role of SIRT1 in regulation of LPS- or two ethanol metabolites-induced TNF-alpha production in cultured macrophage cell lines. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G1047–G1053. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00016.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang XD, Lamb A, Chen LF. Methylation, a new epigenetic mark for protein stability. Epigenetics. 2009;4:429–433. doi: 10.4161/epi.4.7.9787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ea CK, Baltimore D. Regulation of NF-kappaB activity through lysine monomethylation of p65. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18972–18977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910439106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu T, Jackson MW, Wang B, Yang M, Chance MR, Miyagi M, Gudkov AV, Stark GR. Regulation of NF-kappaB by NSD1/FBXL11-dependent reversible lysine methylation of p65. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:46–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912493107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lan F, Nottke AC, Shi Y. Mechanisms involved in the regulation of histone lysine demethylases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:316–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cloos PA, Christensen J, Agger K, Helin K. Erasing the methyl mark: histone demethylases at the center of cellular differentiation and disease. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1115–1140. doi: 10.1101/gad.1652908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsukada Y, Fang J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Warren ME, Borchers CH, Tempst P, Zhang Y. Histone demethylation by a family of JmjC domain-containing proteins. Nature. 2006;439:811–816. doi: 10.1038/nature04433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu T, Jackson MW, Singhi AD, Kandel ES, Yang M, Zhang Y, Gudkov AV, Stark GR. Validation-based insertional mutagenesis identifies lysine demethylase FBXL11 as a negative regulator of NFkappaB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16339–16344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908560106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ganesh L, Yoshimoto T, Moorthy NC, Akahata W, Boehm M, Nabel EG, Nabel GJ. Protein methyltransferase 2 inhibits NF-kappaB function and promotes apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3864–3874. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.10.3864-3874.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Covic M, Hassa PO, Saccani S, Buerki C, Meier NI, Lombardi C, Imhof R, Bedford MT, Natoli G, Hottiger MO. Arginine methyltransferase CARM1 is a promoter-specific regulator of NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression. EMBO J. 2005;24:85–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pickart CM. Mechanisms underlying ubiquitination. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:503–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Natoli G, Chiocca S. Nuclear ubiquitin ligases, NF-kappaB degradation, and the control of inflammation. Sci Signal. 2008;1:e1. doi: 10.1126/stke.11pe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saccani S, Marazzi I, Beg AA, Natoli G. Degradation of promoter-bound p65/RelA is essential for the prompt termination of the nuclear factor kappaB response. J Exp Med. 2004;200:107–113. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ryo A, Suizu F, Yoshida Y, Perrem K, Liou YC, Wulf G, Rottapel R, Yamaoka S, Lu KP. Regulation of NF-kappaB signaling by Pin1-dependent prolyl isomerization and ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of p65/RelA. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1413–1426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00490-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ganesh L, Burstein E, Guha-Niyogi A, Louder MK, Mascola JR, Klomp LW, Wijmenga C, Duckett CS, Nabel GJ. The gene product Murr1 restricts HIV-1 replication in resting CD4+ lymphocytes. Nature. 2003;426:853–857. doi: 10.1038/nature02171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Burstein E, Hoberg JE, Wilkinson AS, Rumble JM, Csomos RA, Komarck CM, Maine GN, Wilkinson JC, Mayo MW, Duckett CS. COMMD proteins, a novel family of structural and functional homologs of MURR1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22222–22232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501928200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maine GN, Mao X, Komarck CM, Burstein E. COMMD1 promotes the ubiquitination of NF-kappaB subunits through a cullin-containing ubiquitin ligase. EMBO J. 2007;26:436–447. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rodrigues L, Filipe J, Seldon MP, Fonseca L, Anrather J, Soares MP, Simas JP. Termination of NF-kappaB activity through a gammaherpesvirus protein that assembles an EC5S ubiquitin-ligase. EMBO J. 2009;28:1283–1295. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tanaka T, Grusby MJ, Kaisho T. PDLIM2-mediated termination of transcription factor NF-kappaB activation by intranuclear sequestration and degradation of the p65 subunit. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:584–591. doi: 10.1038/ni1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lawrence T, Bebien M, Liu GY, Nizet V, Karin M. IKK[alpha] limits macrophage NF-[kappa]B activation and contributes to the resolution of inflammation. Nature. 2005;434:1138–1143. doi: 10.1038/nature03491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang XJ. Multisite protein modification and intramolecular signaling. Oncogene. 2005;24:1653–1662. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang XJ, Seto E. Lysine acetylation: codified crosstalk with other posttranslational modifications. Mol Cell. 2008;31:449–461. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Suganuma T, Workman JL. Crosstalk among Histone Modifications. Cell. 2008;135:604–607. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sims RJ, III, Reinberg D. Is there a code embedded in proteins that is based on post-translational modifications? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:815–820. doi: 10.1038/nrm2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang XD, Tajkhorshid E, Chen L-F. Functional Interplay between Acetylation and Methylation of the RelA Subunit of NF-κB. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:2170–2180. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01343-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thoms HC, Loveridge CJ, Simpson J, Clipson A, Reinhardt K, Dunlop MG, Stark LA. Nucleolar targeting of RelA(p65) is regulated by COMMD1-dependent ubiquitination. Cancer Res. 2010;70:139–149. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kweon SM, Wang B, Rixter D, Lim JH, Koga T, Ishinaga H, Chen LF, Jono H, Xu H, Li JD. Synergistic activation of NF-kappaB by nontypeable H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae is mediated by CK2, IKKbeta-IkappaBalpha, and p38 MAPK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen LY, Pan WW, Chen M, Li JD, Liu W, Chen G, Huang S, Papadimos TJ, Pan ZK. Synergistic induction of inflammation by bacterial products lipopolysaccharide and fMLP: an important microbial pathogenic mechanism. J Immunol. 2009;182:2518–2524. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0713933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jamaluddin M, Tian B, Boldogh I, Garofalo RP, Brasier AR. Respiratory syncytial virus infection induces a reactive oxygen species-MSK1-phospho-Ser-276 RelA pathway required for cytokine expression. J Virol. 2009;83:10605–10615. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01090-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Furusawa J, Funakoshi-Tago M, Tago K, Mashino T, Inoue H, Sonoda Y, Kasahara T. Licochalcone A significantly suppresses LPS signaling pathway through the inhibition of NF-kappaB p65 phosphorylation at serine 276. Cell Signal. 2009;21:778–785. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Basseres DS, Baldwin AS. Nuclear factor-kappaB and inhibitor of kappaB kinase pathways in oncogenic initiation and progression. Oncogene. 2006;25:6817–6830. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Arun P, Brown MS, Ehsanian R, Chen Z, Van WC. Nuclear NF-kappaB p65 phosphorylation at serine 276 by protein kinase A contributes to the malignant phenotype of head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5974–5984. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Joo JH, Jetten AM. NF-kappaB-dependent transcriptional activation in lung carcinoma cells by farnesol involves p65/RelA(Ser276) phosphorylation via the MEK-MSK1 signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16391–16399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800945200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Briones J, Moga E, Espinosa I, Vergara C, Alvarez E, Villa J, Bordes R, Delgado J, Prat J, Sierra J. Bcl-10 protein highly correlates with the expression of phosphorylated p65 NF-kappaB in peripheral T-cell lymphomas and is associated with clinical outcome. Histopathology. 2009;54:478–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Morotti A, Parvis G, Cilloni D, Familiari U, Pautasso M, Bosa M, Messa F, Arruga F, Defilippi I, Catalano R, Rosso V, Carturan S, Bracco E, Guerrasio A, Saglio G. CD7/CD56-positive acute myeloid leukemias are characterized by constitutive phosphorylation of the NF-kB subunit p65 at Ser536. Leukemia. 2007;21:1305–1306. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Manna SK, Manna P, Sarkar A. Inhibition of RelA phosphorylation sensitizes apoptosis in constitutive NF-kappaB-expressing and chemoresistant cells. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:158–170. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang J, An H, Mayo MW, Baldwin AS, Yarbrough WG. LZAP, a putative tumor suppressor, selectively inhibits NF-kappaB. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:239–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ito K. Impact of post-translational modifications of proteins on the inflammatory process. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:281–283. doi: 10.1042/BST0350281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yang SR, Wright J, Bauter M, Seweryniak K, Kode A, Rahman I. Sirtuin regulates cigarette smoke-induced proinflammatory mediator release via RelA/p65 NF-kappaB in macrophages in vitro and in rat lungs in vivo: implications for chronic inflammation and aging. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L567–L576. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00308.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ishinaga H, Jono H, Lim JH, Komatsu K, Xu X, Lee J, Woo CH, Xu H, Feng XH, Chen LF, Yan C, Li JD. Synergistic induction of nuclear factor-kappaB by transforming growth factor-beta and tumour necrosis factor-alpha is mediated by protein kinase A-dependent RelA acetylation. Biochem J. 2009;417:583–591. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gringhuis SI, den Dunned J, Litjens M, van Het Hof B, van Kooyk Y, Geijtenbeek TB. C-type lectin DC-SIGN modulates Toll-like receptor signaling via Raf-1 kinase-dependent acetylation of transcription factor NF-kappaB. Immunity. 2007;26:605–616. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kwon HS, Brent MM, Getachew R, Jayakumar P, Chen LF, Schnolzer M, McBurney MW, Marmorstein R, Greene WC, Ott M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein inhibits the SIRT1 deacetylase and induces T cell hyperactivation. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dai Y, Rahmani M, Dent P, Grant S. Blockade of histone deacetylase inhibitor-induced RelA/p65 acetylation and NF-kappaB activation potentiates apoptosis in leukemia cells through a process mediated by oxidative damage, XIAP downregulation, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5429–5444. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5429-5444.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lee H, Herrmann A, Deng JH, Kujawski M, Niu G, Li Z, Forman S, Jove R, Pardoll DM, Yu H. Persistently activated Stat3 maintains constitutive NF-kappaB activity in tumors. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Choi KC, Jung MG, Lee YH, Yoon JC, Kwon SH, Kang HB, Kim MJ, Cha JH, Kim YJ, Jun WJ, Lee JM, Yoon HG. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate, a histone acetyltransferase inhibitor, inhibits EBV-induced B lymphocyte transformation via suppression of RelA acetylation. Cancer Res. 2009;69:583–592. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sung B, Pandey MK, Ahn KS, Yi T, Chaturvedi MM, Liu M, Aggarwal BB. Anacardic acid (6-nonadecyl salicylic acid), an inhibitor of histone acetyltransferase, suppresses expression of nuclear factor-kappaB-regulated gene products involved in cell survival, proliferation, invasion, and inflammation through inhibition of the inhibitory subunit of nuclear factor-kappaBalpha kinase, leading to potentiation of apoptosis. Blood. 2008;111:4880–4891. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fischle W, Wang Y, Allis CD. Histone and chromatin cross-talk. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:172–183. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]