As nurses, we all know many clients who have been diagnosed with HIV but chose not to enter care until very late in the course of their disease and who now have an AIDS diagnosis and opportunistic infections. Others, already in care and requiring maintenance therapy to continue doing well, inexplicably drop out of care for several months or years. In an effort to more fully understand these phenomena, we conducted a survey in 2007 at the University of Mississippi Medical Center clinic, with a convenience sample of all patients who attended clinic on the days that we had a data collector available (Konkle-Parker, Amico & Henderson, 2009). Eligible patients were those who self-reported a delay in entering HIV care for at least six months after diagnosis or at least one gap in care of six months or more since starting in HIV care.

The survey was a qualitative semi-structured interview based on questions from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Medical Monitoring Project (Table 1; Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, 2008). Open-ended questions were used to ask about participants’ barriers and facilitators to entering and staying in HIV clinical care, responses were simultaneously coded by data collectors, and the data were analyzed quantitatively.

Table 1.

Interview Questions

|

For those who reported a gap in care of six months or more:

|

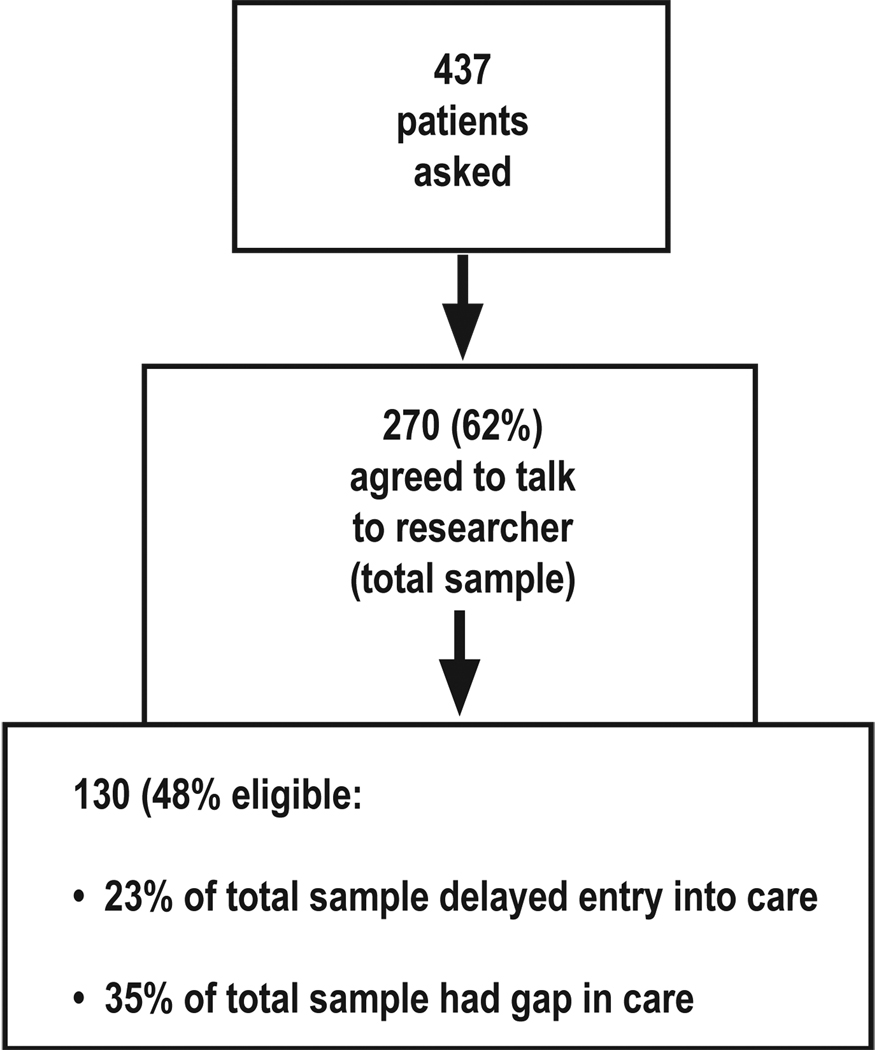

See Figure 1 for enrollment description, showing that almost half of the patients who agreed to speak with the researcher had experienced a delay in entering care of at least six months after diagnosis and/or experienced at least one gap in care of six months or more since they started care. Characteristics of the sample are in Table 2 and very much reflected the clinic population from which the sample was drawn.

Figure 1.

Enrollment

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics

| Characteristic | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Eligibility criteria | 62 (48% of eligible participants) delayed entry into HIV care >6 months 94 (72% of eligible participants) had a gap in HIV care of >6 months |

| Race | 81% Black; 18% White |

| Gender | 62% male |

| Sexual identity | 68% self-reported as heterosexual |

| Education | 24% had less than a high school education |

| Income | 42% were on disability |

| Employment status | 57% were living on an income of less than $10,000 per year |

| Length of time with HIV diagnosis | 43% had been diagnosed more than 10 years previously |

An unexpected number of individuals described denial as a reason that they didn’t enter care (74% described it as a barrier with 43% as the main barrier) and kept them from staying in care (27% described it as a barrier), with worries about privacy being another frequently reported barrier to entering care (31% described it as a barrier with 13% as the main barrier). These personal attitudes or beliefs made up a greater percentage of the barriers reported by those who delayed entry into care (93% of these individuals reported at least one personal barrier) as compared to structural barriers, but also an important number of those with gaps in care (72% of those with gaps in care reported at least one personal barrier).

When reporting facilitators to entering care, many were beyond the control of the nurse: 52% of those who delayed entry into care and 31% of those who had a gap in care said that an important facilitator for them was feeling worse or entering the hospital. An important minority of individuals, however, also reported that deciding to take care of their health was an important facilitator for entering or re-entering care (39% of those who delayed entry into care and 50% of those who had a gap in care reported this as one of their facilitators; 19% and 33% respectively said that it was the main facilitator for getting them into or back into care). This is an area where nurses can be instrumental, in motivating our clients or clients’ friends to take care of themselves, and to see HIV care as an important coping mechanism in the process of taking care of themselves rather than as a burden.

Other important facilitators that nurses can keep in mind for helping clients to enter and re-enter care were: a) accepting their diagnosis (facilitator for 11% of those delaying entry into care and 2% of those with a gap in care); b) stopping drinking or using drugs (facilitator for 7% of both those who delayed entry into care and those who had a gap in care); c) feeling less worried about their privacy (facilitator for 3% of both those who delayed entry into care and those who had a gap in care); d) health care provider reminding them (facilitator for 3% of those delaying entry into care and 2% of those with a gap in care; all these individuals also reported this as their main facilitator).

What this information tells us is that personal attitudinal barriers were more important than structural barriers for keeping this group of individuals who successfully entered care from doing it in a timely manner and from doing it consistently. Personal barriers were more important than structural barriers in delaying these individuals in entering care, but were also important in keeping them from consistent care, though slightly less so than structural barriers. This may help us to avoid concentrating only on the structural facilitators (providing transportation, funding for care and medications, child care, etc.). Finding out the attitudes, beliefs, and mental health issues that get in the way of timely and uninterrupted care and addressing those barriers may be more useful in convincing our clients to accept their diagnosis, and helping them to take care of their health.

REFERENCES

- Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention. Medical Monitoring Project (MMP) [Retrieved April 21, 2007];2008 June 28; from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/treatment/mmp/index.htm.

- Konkle-Parker DJ, Amico KR, Henderson HM. Barriers and facilitators to engagement in HIV clinical care in the Deep South: Results from semi-structured patient interviews. Manuscript submitted for publication. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]