Abstract

Many studies have shown that the dynamic motions of individual protein segments can play an important role in enzyme function. Recent structural studies on the gluconeogenic enzyme PEPCK demonstrate that PEPCK contains a 10-residue Ω-loop domain that acts as an active site lid. Based upon these structural studies we have previously proposed a model for the mechanism of PEPCK catalysis in which the conformation of this mobile lid-domain is energetically coupled to ligand binding resulting in the closed conformation of the lid, necessary for correct substrate positioning, becoming more energetically favorable as ligands associate with the enzyme. Here we test this model by the introduction of a point mutation (A467G) into the center of the Ω-loop lid that is designed to increase the entropic penalty for lid closure. Structural and kinetic characterization of this mutant enzyme demonstrates that the mutation has decreased the favorability of the enzyme adapting the closed lid conformation. As a consequence of this shift in the equilibrium defining the conformation of the active site lid, the enzyme’s ability to stabilize the reaction intermediate is reduced resulting in catalytic defect. This stabilization is initially surprising, as the lid domain makes no direct contacts with the enolate intermediate formed during the reaction. Furthermore, during the conversion of OAA to PEP, the destabilization of the lid closed conformation results in the reaction becoming decoupled as the enolate intermediate is protonated rather than phosphorylated resulting in the formation of pyruvate. Taken together, the structural and kinetic characterization of A467G-PEPCK support our model of the role of the active site lid in catalytic function and demonstrate that the shift in the lowest energy conformation between open and closed lid states is a function of the free energy available to the enzyme through ligand binding and the entropic penalty for ordering of the ten-residue Ω-loop lid domain.

Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK1) catalyzes the reversible decarboxylation and phosphorylation of OAA to form PEP as shown in Scheme 1. While in vitro the reaction is freely reversible, the overall consensus is that in most organisms PEPCK operates primarily in the direction of PEP synthesis. PEPCK is a metal-requiring enzyme demonstrating an absolute requirement on divalent cations for activity. Mn2+ is the most activating cation in the GTP dependent isoforms (1–4). In addition a second divalent metal ion is required for the reaction, as the metal-nucleotide complex is the true substrate. In higher eukaryotes PEPCK is present as both a cytosolic (cPEPCK) and mitochondrial (mPEPCK) isoform, with the relative distribution of these two isoforms being species dependant. In its biological role, cPEPCK functions as a key cataplerotic enzyme; in addition to its well-characterized role in gluconeoenesis, PEPCK participates in glyceroneogenesis and triglyceride biosynthesis as well as the synthesis of serine (reviewed in(5)). In contrast, the role of mPEPCK in metabolic function is less understood.

Scheme 1.

The PEPCK catalyzed interconversion of OAA and PEP.

In general, the structural data on PEPCK illustrate the presence of a specialized cationic active site, dominated by the juxtaposition of the two aforementioned divalent metal ions and the positioning of specific lysine and arginine residues, that is well suited to carry out both the decarboxylyation/carboxylation and phosphoryl transfer half-reactions as well as the stabilization of the enolate intermediate postulated to form along the stepwise reaction pathway (6). Due to the inherent reactivity of the enolate intermediate, primarily its energetically favorable protonation resulting in pyruvate, we have suggested that the protection/stabilization of the enolate by the enzyme is key to the reversible nature of the PEPCK catalyzed reaction (Scheme 1) (6).

An informative aspect of the recent structural studies on the GTP-dependent isozyme from rat is the illumination of the previously unappreciated role of conformational changes occurring at the active site during the catalytic cycle (6–9). The most prevalent mobile feature illustrated by the structural work is a ten-residue Ω-loop lid domain, reminiscent of a similar domain in TIM (10–13). An essential role for this domain in PEPCK mediated catalysis is suggested by the structural data on PEPCK demonstrating that only upon closure of the lid domain are the substrates positioned correctly for phosphoryl transfer to occur (9). In addition to the essential role lid closure is proposed to play in positioning the substrates for catalysis, closure of the lid may additionally sequester the enolate intermediate, allowing PEPCK-mediated catalysis to occur via the mechanism illustrated in Scheme 1.

The dynamic nature of lid opening and closing begs the question as to what the energetic driving force for lid closure is and what specific role lid closure plays in the catalytic cycle. As the structural data demonstrate that no new direct contacts are made between the lid when it closes in the presence of substrates as compared to its closing in their absence, we have previously proposed a model consistent with the notion originally put forth by Fersht (14). In this model, the thermodynamic favorability of the enzyme adapting the closed lid (active) state increases as ligands add to the enzyme, with a portion of their Gibbs free energy of binding being partitioned to the protein. This energy partitioning has the effect of remodeling the free energy profile for the protein and offsetting the entropic penalty associated with the lid assuming an ordered closed conformation rather than a conformationally dynamic open (inactive) state (9). Previous solid-state and solution NMR studies on TIM (15, 16) are consistent with the model we propose for PEPCK lid motion (above and (9)), as these studies on TIM suggest that the position of the open-close equilibrium is dependent on the nature of the bound ligand.

In order to further probe the role of lid closure in PEPCK catalytic function and to test our model, that the penalty for the reduction in configurational entropy of the enzyme upon lid ordering is paid by the interaction free energy of substrates/intermediates we have generated a lid mutation (A467G, Figure 1) that is designed to increase the entropic penalty for ordering of the lid in the closed conformation. Structural and kinetic characterization of this mutant demonstrate that consistent with our model for lid closure, the A467G mutation results in a decrease in the propensity for the lid to adapt its closed conformation. As a functional consequence, this disruption in the energetics of lid closure results in an observed decrease in the fidelity of the conversion of OAA to PEP through the decoupling of the reaction to pyruvate. In addition, even though the closed lid makes no direct contacts with the substrates, the kinetic data are consistent with the destabilization of the closed lid conformation resulting in a decrease in PEPCK’s ability to stabilize the enolate intermediate. This loss of enolate stabilization significantly impacts the kinetics of the reaction resulting in a kcat/KM for OAA that is only 2% of the WT value.

Figure 1.

The sequence of the active site lid domain (residues 462-476). The site of introducing the glycine (467) is indicated above the sequence.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The nucleotides (GTP, GDP, IDP, ITP, and ADP) and 2-phosphoglycolate were purchased from Sigma. PEP and NADH were from Chem-Impex. DTT was from Gold Bio-Tech. HEPES buffer was from Research Organics. Oxalic acid was from Fluka. β-Sp was synthesized and purified as previously described (17). Glutathione Uniflow Resin was purchased from Clontech. HiQ, P6DG, and Chelex resins were from Bio-Rad. All other materials were of the highest grade commercially available.

Enzymes

Malate dehydrogenase (22,976 U/mL, 50% glycerol solution) and lactate dehydrogenase (6000 U/mL, AmSO4 suspension) were from Calzyme Laboratories. Pyruvate kinase (10 mg/mL, AmSO4 suspension) was from ROCHE.

PEPCK expression and purification

Recombinant, WT rat cPEPCK was expressed and purified as previously described (8) with the following alterations. All buffers in the purification included 10mM DTT, and were treated with chelex resin for 10 min prior to filter degassing. The molar extinction coefficient used to determine protein concentration is 1.65 mL mg−1 as determined experimentally (18).

Generation of A467G PEPCK

Recombinant rat cPEPCK in PGEX-4T-2 was used as the starting vector to create the A467G mutation. The forward primer (5′-GAGGCCACCGCTGGTGCAGAGCATAAGG-3′) and its reverse complement were utilized with the Stratagene Quik Change protocol. The resultant mutated DNA was isolated with a Hurricane cleanup kit from Gerard Biotech and subsequently sequenced to confirm the presence of the desired mutation and the absence of any additional mutations introduced via the PCR protocol. The plasmid DNA was transformed into E. Coli BL-21(DE3) electro-competent cells for expression. Expression and purification of the mutant A467G followed the same protocol as the WT enzyme with the same modifications described above.

Crystallization

Crystals of the complexes of A467G PEPCK were obtained as previously described for the WT enzyme (9).

Data Collection

Data on the cryo-cooled A467G PEPCK-Mn2+-βSP-Mn2+GTP, and A467G PEPCK-Mn2+-oxalate-Mn2+GTP complexes maintained at 100K were collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory, Beamline 11-1, Menlo Park, CA. Data on the A467G PEPCK-Mn2+-PGA-Mn2+GDP crystal maintained at 100K was collected using a RU-H3R rotating copper anode X-ray generator with Blue Confocal Osmic mirrors and a Rigaku Raxis IV++ detector. All data were integrated and scaled with HKL-2000 (19). Final data statistics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Crystallographic data and model statistics for the structures of A467G PEPCK.

| A467G-Mn2+-βSP-Mn2+GTP | A467G-Mn2+-PGA-Mn2+GDP | A467G-Mn2+-oxalate-Mn2+GTP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9 | 1.54 | 0.9 |

| Space group | P21 | P21 | P21 |

| Unit cell | a = 44.3Å | a = 62.1 Å | a = 62.0 Å |

| b = 119.1 Å | b =119.5 Å | b = 119.6 Å | |

| c = 60.1 Å | c = 87.0 Å | c = 87.1 Å | |

| α = γ = 90.0° | α = γ = 90.0° | α = γ = 90.0° | |

| β = 111.2° | β = 107.2° | β = 106.9° | |

| Resolution Limits, Å | 20.6-1.25 | 35.93-2.10 | 33.24-1.75 |

| No. of unique reflections | 152044 | 68697 | 118295 |

| Completenessa, % (all data) | 95.0 (67.2) | 97.2 (80.3) | 96.7 (94.9) |

| Redundancya | 6.9 (3.5) | 7.0 (4.9) | 7.1 (6.9) |

| I/σ(I)a | 28.2 (2.1) | 10.0 (1.6) | 18.0 (2.3) |

| Rmerge a | 0.04 (0.46) | 0.1(0.59) | 0.06 (0.55) |

| No. of ASU molecules | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Rfreea | 17.4(34.2) | 24.7(34.1) | 22.8(33.1) |

| Rworka | 14.8(32.7) | 19.0(28.2) | 17.9(29.3) |

| Estimated coordinate error based on maximum likelihood, Å | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.10 |

| Bond length RMSD, Å | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Bond angle RMSD,° | 2.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Ramachandran Statistics (preferred, allowed, outliers), % | 96.9, 2.4, 0.7 | 96.4, 3.0, 0.6 | 96.5, 2.7, 0.8 |

| State of Active Site Lid | Molecule A: Open | Molecule A: Open | Molecule A: 70% closed |

| Molecule B: Open | Molecule B: Open |

Values in parentheses represent statistics for data in the highest resolution shells.

Structure determination and refinement

The A467G enzyme structures were solved by the molecular replacement method using MOLREP (20) in the CCP4 package (21) and the previously solved rat cPEPCK structures of the same complexes (PDB ID: 3DT4, 3DT7 and 3DTB)(9). For each complex, the molecular replacement solution was refined using Refmac5 followed by manual model adjustment and rebuilding using COOT (22). Ligand, metal, and water addition and validation were also performed in COOT. A final round TLS refinement was performed for all models in Refmac5. A total of 5 groups per chain for the A467G PEPCK-Mn2+-βSP-Mn2+GTP and A467G PEPCK-Mn2+-oxalate-Mn2+GTP models were used as refinements using greater than five groups per chain did not significantly improve R/Rfree. A total of 20 groups per chain for the A467G PEPCK-Mn2+-PGA-Mn2+GDP model were used. The optimum TLS groups were determined by submission of the PDB files to the TLSMD server [http://skuld.bmsc.washington.edu/~tlsmd/] (23–25). Final model statistics are presented in Table 1.

Kinetic Experiments

All kinetic data were collected on a Cary 100 spectrophotometer equipped with a multi-cell changer and a temperature bath. PEPCK activity was assayed in both the physiological direction of PEP formation and the reverse direction of OAA formation using modifications of previously published assays (1, 18, 26). All assays were performed at 25 °C, in a final volume of 1 mL and monitored spectrophotometrically by following the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm due to the oxidation of NADH. The oxidation of NADH was recorded in real time so as to allow the calculation of a rate of enzyme activity from the extinction coefficient for NADH (27). In all kinetic assays the concentration of PEPCK utilized was 14–36 nM and 43–86 nM for the WT and A467G enzyme forms, respectively.

Assay A: OAA+GTP→PEP+CO2+GDP

The decarboxylation and phosphorylation of OAA to form PEP was carried out in a reaction mixture containing 50mM HEPES pH 7.5, 10mM DTT, 4mM MgCl2, 500 μM GTP, 1mM ADP, 200 μM MnCl2, 150 μM NADH, 30 units of LDH, 50 μg PK, and 350 μM OAA. All enzyme-catalyzed rates that use OAA as the substrate have been corrected for the non-enzymatic decarboxylation of OAA forming pyruvate (Assays A, C, and D). This assay was started by the addition of OAA to each cuvette. OAA and GTP concentrations were varied in turn to obtain the respective Michaelis constants. When OAA was varied, the reaction was performed as above. When GTP was the varied substrate, MgCl2 was also varied to keep a constant 4:1 ratio of metal to nucleotide. The reaction mixture was preincubated at 25 °C for 5 min prior to addition of OAA.

Assay B: PEP+GDP+CO2→OAA+GTP

The dephosphorylation and carboxylation of PEP to form OAA was measured in a reaction mixture consisting of 50mM HEPES pH 7.5, 10mM DTT, 4mM MnCl2, 500 μM GDP, 150 μM NADH, 2mM PEP, 10 units of MDH, and 50mM KHCO3. This assay was started by the addition of PEPCK to the reaction mix in the cuvette. PEP, KHCO3 and GDP concentrations were varied in turn to obtain the respective Michaelis constants. When GDP was the varied substrate MnCl2 was also varied to keep a constant metal to nucleotide ratio of 4:1. The concentration of dissolved CO2 was calculated from the added KHCO3 as previously described (28).

Assay C: OAA+GTP→pyruvate+GTP+CO2

The decoupling of the PEPCK catalyzed reaction (Assay A) through the production of pyruvate was measured in the same reaction mix as assay A. The only exception was that the coupling enzyme PK and its required nucleotide (ADP) were omitted from the reaction mix so that the direct production of pyruvate by PEPCK could be monitored. Each cuvette consisted of 50mM HEPES pH 7.5, 10mM DTT, 4mM MgCl2, 500 μM GTP, 200 μM MnCl2, 150 μM NADH, 30 units of LDH, and 350 μM OAA. Each assay was initiated by the addition of OAA that was subsequently varied to obtain a Michaelis constant. The reaction mixture was preincubated at 25 °C for 5 min prior to addition of OAA.

Assay D: OAA+GDP→pyruvate+GDP+CO2

The PEPCK catalyzed decarboxylation of OAA without subsequent phosphoryl transfer was carried out under identical reaction conditions to assay C except that 500 μM GDP was substituted for GTP (18). A Michaelis constant for OAA was determined by varying OAA concentration. Each assay was started by the addition of OAA to each cuvette. The reaction mixture was preincubated at 25 °C for 5 min prior to the addition of OAA.

Inhibitor Assays

Inhibition experiments with oxalate and PGA were carried out using assay B. A Michaelis constant for PEP was determined at several different concentrations of each inhibitor. The inhibition by β-SP was carried out using assay A because β-SP is a substrate for MDH. A Michaelis constant for OAA was determined at several concentration of β-SP.

Data analysis

All kinetic data was analyzed using SigmaPlot® 11. In assays A-D the slope of the line was used to calculate a rate of enzyme activity. Due to the production of pyruvate during the OAA → PEP reaction (Assay A) in the A467G mutant, the data were corrected for this activity using the KM and Vmax values obtained for the enzyme from Assay C for the A467G enzyme. These two values were used in equation 1 to calculate the theoretical rate of catalyzed pyruvate formation at each substrate concentration used in Assay A for the A467G enzyme. This calculated rate was subtracted from the observed activity after correction for non-enzymatic, spontaneous OAA decarboxylation as described above. All kinetic data were fit nonlinearly to the Henri-Michaelis-Menten relationship (equation 1) to determine KM and Vmax values. A kcat value was calculated from the Vmax using a molecular weight of 69 415 Da. For the inhibition studies, the rate of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction was calculated from the slope of the line for all data points. For the inhibition of PEPCK by PGA and oxalate, the rate data was plotted together and globally fit to equation 1 resulting in a singular value for Vmax and KM,app values at each concentration of inhibitor. The resulting KM,app values were re-plotted against the concentration of inhibitor giving a linear fit to equation 2 that was used to calculate the Ki value for each inhibitor. For βSP2 the data at each concentration of inhibitor was fit individually to equation 1 resulting in KM,app and Vmax,app values. From these values, the ratio KM,app/Vmax,app was calculated and these values were plotted as a function of βSP concentration and fit to equation 3 to determine the Ki value for the competitive binding effect.

| eq.1 |

| eq.2 |

| eq.3 |

In equations 1–3, ν is the initial velocity, Vmax is the maximal velocity achieved, [S] is the concentration of substrate at each velocity, KM is the Michaelis constant for each respective substrate, [I] is the inhibitor concentration, and Ki is the inhibition constant.

Fluorescence Quenching

Fluorescence quenching experiments were performed using a steady state PTI instrument with temperature control. Each assay was carried out in a triangular cuvette at 15 °C with constant stirring. The samples contained 50mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10mM DTT, 1mM MnCl2, 200 μM KCl, and PEPCK (1–5 μM). The emission was monitored at 330 nm after excitation at 295 nm. The sample was titrated with an identical solution, which also contained IDP or ITP. Inosine nucleotides were substituted for the guanosine nucleotides utilized in the kinetic studies to reduce inner filter effects. The binding constants and quenching maximums were determined by a nonlinear least squares fit of the titration data to equation 4 (IDP) or equation 5 (ITP).

| eq.4 |

In equation 4, QL is the quenching at each ligand concentration, QM is the maximal quenching observed, KD is the dissociation constant of the complex, LT is the ligand concentration titrated into the sample, and PT is the protein concentration.

| eq.5 |

In equation 5, QL is the quenching at each ligand concentration, QM is the maximal quenching observed, KD is the dissociation constant of the complex, LT is the ligand concentration titrated into the sample. Equation 5 was utilized for the ITP binding data as poor fits to the data were obtained when using equation 4. We presume that these poor fits were the result of contamination of the ITP solution with low levels of IDP that did not allow for a discrete treatment of the distribution of species using equation 4. Representative binding isotherms for WT and A467G are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Binding isotherms illustrating the binding of ITP to (A) Wild-type and (B) A467G PEPCK as measured by intrinsic protein fluorescence quenching and described in the methods.

Results

Kinetic experiments were performed to determine the effect of the mutation upon the kinetic constants for the reaction in both the direction of PEP formation and OAA formation as well as the OAA decarboxylase activity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characterization of wild-type and A467G cytosolic PEPCK. All experiments performed at 25 °C.

| (A) OAA + GTP → PEP + GDP + CO2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | KM(μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (M−1 s−1) | ||

| OAA | GTP | OAA | GTP | ||

| Wild-type | 52 ± 6 | 68 ± 4 | 54 ± 0.2 | 1.0 × 106 | 7.9 × 105 |

| A467G | 749 ± 67 | 47 ± 17 | 14 ± 0.1 | 1.9 × 104 | 2.7 × 105 |

| (B) PEP + CO2 + GDP → OAA + GTP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | KM (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (M−1 s−1) | ||||

| PEP | GDP | CO2 | PEP | GDP | CO2 | ||

| Wild-type | 294 ± 16 | 39 ± 2 | 1194 ± 109 | 19 ± 0.8 | 6.6 × 104 | 5.1 × 105 | 1.6 × 104 |

| A467G | 63 ± 11 | 70 ± 8 | 814 ± 98 | 1 ± 0.1 | 1.5 × 104 | 1.4 × 104 | 1.2 × 103 |

| (C) Pyruvate production during the OAA + GTP → PEP + GDP + CO2 reaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | KM (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (M−1 s−1) |

| OAA | |||

| Wild-type | ND | ND | ND |

| A467G | 512 ± 43 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 5.0 × 103 |

| (D) Decarboxylation Half-Reaction; OAA + GDP → Pyruvate + GDP + CO2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| KM (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (M−1 s−1) | |

| Enzyme | OAA | ||

| Wild-type | 117 ± 11 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.0 × 104 |

| A467G | 970 ± 118 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.0 × 103 |

| (E) Substrate/Substrate Analogue Affinities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | KD (μM) | KD (μM) | KI (μM) | KI (μM) | KI (μM) |

| ITP | IDP | βSP | PGA | oxalate | |

| Wild-type | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 11.6 ± 0.4 | 26 ± 1 | 2530 ± 13 | 106 ± 6 |

| A467G | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 8.0 ± 0.3 | 50 ± 3 | 1460 ± 48 | 860 ± 33 |

ND = no pyruvate formation detected

Kinetic Characterization of recombinant WT and A467G PEPCK

OAA → PEP

In the physiological direction, where OAA is converted to PEP, a mixed metal assay (assay A) was utilized, as the background rate of non-enzymatic OAA decarboxylation is lower in the presence of high concentrations of magnesium when compared to using manganese as the sole divalent cation. Utilizing this assay, A467G PEPCK has a 14-fold higher KM value for OAA than WT (Table 2A). This increase in KM is coupled with a reduction in kcat (26% of WT), resulting in a reduction in catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) by nearly two orders of magnitude (1.9% of WT). Conversely, there is little change in the KM for GTP (factor of 1.4), resulting in the kcat/KM,GTP decreasing by less than a factor of three. As described below, A467G produces pyruvate during the turnover of OAA to PEP. The data for the formation of PEP that is coupled to pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase was corrected for this pyruvate formation activity.

PEP → OAA

In the reverse direction PEPCK catalyzes the formation of OAA from PEP (assay B). The mutant A467G showed a decrease in the KM value for PEP (21% of WT) (Table 2B). In contrast, the A467G mutation had a kcat reduced to 5% of the WT value. The combination of a decrease in KM and a decrease in kcat, result in only a factor of four reduction in the catalytic efficiency of A467G relative to WT. In contrast, due to a slight increase in the KM value for GDP, kcat/KM for GDP decreases to 3% of WT.

Pyruvate formation

It has been well documented that PEPCK will catalyze the production of pyruvate from OAA (18, 27, 29, 30). With rat cPEPCK at 25 °C, this activity is dependent on the presence of GDP (assay D). When comparing the mutant and WT enzymes, A467G has a KM value seven-fold higher than WT with a modest reduction in kcat(57% of WT). This results in the WT enzyme being 20-fold more efficient at catalyzing the decarboxylation of OAA than A467G (Table 2D).

As the A467G mutation was designed to reduce the favorability of the enzyme adapting the lid closed state, and to test our proposed role for the lid in protecting the enolate intermediate, once formed, from favorable protonation (vide infra), we investigated the ability of the enzyme to catalyze the formation of pyruvate during the catalyzed formation of PEP from OAA (assay C). In the WT enzyme there was no measurable formation of pyruvate at 25 °C. However, the A467G mutant showed a measureable amount of pyruvate formation, albeit with a KM value similar to the elevated KM observed in both the decarboxylation reaction and the overall reaction in the direction of PEP formation, both described above (Table 2C).

Inhibition of WT and A467G PEPCK by substrate analogs

The competitive inhibition of PEPCK by the substrate analogues βSP and PGA and the enolate mimic oxalate have been illustrated previously on both mitochondrial and cytosolic isoforms of PEPCK (7, 26). The kinetic and structural data demonstrate that all three inhibitors are excellent mimics of the respective substrate/intermediate (Figure 3). We utilized the binding constants determined from the inhibition experiments to assess whether the A467G mutation had any affect on substrate and enolate affinity. Both of the substrate analogues, βSP and PGA, have similar affinity for WT and A467G PEPCK (Table 2E). In contrast, the reduction in the affinity of oxalate with A467G (approximately a factor of eight) suggests that by extrapolation the lid mutation has decreased the stabilization of the enolate intermediate by ~ 5.3 kJ mol−1.

Figure 3.

Structures of the OAA and PEP substrates and the enolate intermediate alongside the corresponding analogue utilized in these studies.

Nucleotide binding by fluorescence quenching

The KM values for GDP and GTP suggest that the A467G mutation has little effect on the relative affinity of PEPCK for the nucleotide substrates. This conclusion was confirmed by the direct measurement of the KD values for IDP and ITP by intrinsic protein fluorescence quenching experiments. The inosine nucleotides were substituted in place of guanosine to reduce the inner filter effect observed when guanosine nucleotides are utilized. PEPCK utilizes inosine and guanosine nucleotides with similar catalytic efficiency, while ITC experiments on the human enzyme have demonstrated the exocyclic C-2 amino group of guanosine nucleotides increases the affinity of the enzyme for guanosine nucleotides by approximately an order of magnitude over that of the inosine analogue (31). As shown in Table 2E, WT PEPCK has a KD for ITP of 0.34 μM while A467G has a KD of 0.50 μM. Meanwhile, the dissociation constants for IDP are 11.6 μM and 8.0 μM for WT and A467G, respectively.

Structures of A467G

In order to demonstrate that the substitution of A467 for glycine decreases the thermodynamic favorability of the enzyme adapting the closed lid conformation but does not alter the structure that the Ω-loop adapts upon closing, the structure of A467G PEPCK in complex with βSP, PGA, and oxalate and either GTP or GDP were determined (Table 1). Identical structural studies on the WT enzyme demonstrated that as the enzyme commits to catalysis the thermodynamic favorability of the enzyme adapting the closed lid conformation increases (9). In the βSP-GTP and PGA-GDP structures, mimicking the Michaelis complexes for the forward and reverse reactions, respectively, the WT enzyme contains two molecules in the ASU with one adapting a closed lid conformation and the other one remaining open. In the oxalate-GTP complex with WT enzyme, the lid was always found to be in a closed conformation. In contrast to those results, and consistent with the design of the mutation, the structures of A467G with βSP-GTP and PGA-GDP were found to only adapt the open lid conformation, consistent with a destabilization of the closed lid state. In a similar fashion, the A467G- Mn2+-oxalate-Mn2+GTP structure also contains two molecules in the ASU in which molecule B possess an open lid conformation. Molecule A was found to partially adapt a closed lid conformation that was manually adjusted to an occupancy of 70% (Figure 4). This results in an overall occupancy of the closed lid conformation for the crystal of 35%, compared to 100% in the WT enzyme. Upon comparison of the closed lid conformation observed in molecule A with the conformation of the closed lid in the WT PEPCK-oxalate-GTP structure (PDB ID: 3DT4), it is observed that the substitution of glycine for alanine does not change the low energy conformation of the closed lid, (Figure 4) consistent with the observed kinetic and binding effects resulting solely from the perturbation of the thermodynamic favorability of the enzyme adapting the closed lid conformation necessary for catalysis.

Figure 4.

The structure of molecule A of the A467G-PEPCK-oxalate-GTP complex. The partial occupancy (0.7) of the closed lid in this molecule is illustrated by the 2Fo−Fc density rendered at 1.3 σ as a blue mesh with the corresponding lid domain rendered as a green stick model colored by atom type. The active site manganese ion and the bound oxalate molecule are rendered as a grey sphere and green stick model, respectively. The location of the A467G mutation is also labeled. Figures were generated using CCP4MG (47).

Discussion

The motional properties of mobile loop regions have been demonstrated in many diverse systems to be essential to enzyme function (15, 16, 32–39). In particular, the Ω-loop lid domain of TIM has been well characterized and it has been demonstrated that removal of a portion of the lid leads to an increase in the production of the reaction side product methylglyoxal. Further, the removal of a portion of the lid in TIM negatively impacts catalytic function, as the lid is no longer able to stabilize the intermediate or the transition states that precede or follow its formation (40). In contrast, mutations in the hinge regions of the Ω-loop of TIM, designed to increase the motional freedom of the lid, while negatively impacting catalytic function, do not result in an increase in the production of methylglyoxal (32). In general, these studies on TIM have demonstrated that the functional nature of this mobile loop domain is an exquisite balance between its rigidity and its flexibility, a property that may be a general feature of all catalytically important mobile loops (16, 32, 37). While EPR studies on S-adenosylmethionine synthetase (33), suggest that the rates of open and closed conformation sampling is identical in the presence and absence of substrates, NMR studies on TIM (15, 16) as well as the crystallographic data on TIM, are consistent with ligand association influencing the most stable, most highly populated conformation of the lid domain. The later data is also consistent with the recent structural studies on PEPCK (9).

While PEPCK and TIM catalyze two drastically different chemical reactions, they both do so via unstable intermediate enolate species that rapidly decompose in solution. Based upon the commonality of a lid domain, the simplest interpretation is that the mobile lid is necessary to allow ligand association/disassociation, but during catalysis is required to provide an environment that sequesters and/or stabilizes the reactive intermediate and gives the enzyme the ability to follow a chemical pathway that is not available in solution due to the instability of the intermediate. Unlike the phosphate ‘gripper’ lid domain of TIM, in PEPCK the closed lid makes no direct contacts with the bound substrates or the enolate intermediate. Therefore, in PEPCK it is not possible that new interactions between the lid and the substrates directly stabilize the lid in the closed state. In light of this observation, an alternative mechanism to describe the energetic driving force behind the transition between open and closed lid states is needed. In general, our model of lid dynamics in PEPCK proposes that not all of the free energy from substrate association goes into forming a tight binding E-S complex, but that some of that energy is partitioned to the protein. This input energy modifies the free energy landscape that defines the conformation of the protein, and results in the closed lid state becoming more thermodynamically favorable as substrates associate (6, 9). This general idea has been presented previously (41, 42). While the mechanism of this free energy partitioning in PEPCK is presently unknown, both the kinetic and structural data presented in this work are consistent with this model. In order to understand the role of the lid domain in the reaction mediated by PEPCK, we have undertaken structural and kinetic studies of a mutant of the enzyme that was designed to alter the equilibrium of the open/close transition.

The Rationale Behind the A467G Mutation

To test the above model of lid dynamics, we desired to increase the entropic penalty for lid closure while maintaining the available interaction energy fixed (i.e. using the same ligands). In order to achieve this goal we postulated that we could engineer a modified lid domain that, while still operating as a singular rigid domain of an Ω-loop (13), has an increased entropic penalty for lid ordering and closure through the introduction of a conformationally more flexible glycine residue (Figure 1). It was decided that the mutation of A467 to glycine would provide such an engineered change. Upon expression and purification of this mutation (A467G), we undertook structural and functional studies in order to determine if the mutation provided data that was consistent with our model of loop function.

Kinetic and Structural Characterization of the A467G Mutation

Structures of the Michaelis and enolate intermediate-like complexes

The A467G-PEPCK structures mimicking the two Michaelis complexes and the enolate intermediate state, which were determined under identical conditions as the previous complexes with wild-type enzyme (9), illustrate that no gross structural changes are induced by the lid mutation. Further, with the exception of rotomeric state of Y235 in the A467G-oxalate-GTP complex discussed below, the enzyme-substrate contacts in the A467G complexes are identical to the open complexes of the WT enzyme previously determined (Figure 5). However, consistent with the design of the mutation, the introduction of the glycine linker has resulted in the lid-closed state being less thermodynamically favorable (Table 1). This results in the closed lid state only being observed at a low population in the A467G-oxalate-GTP complex, and not at all in the two Michaelis-like complexes (A467G-βSP-GTP and A467G-PGA-GDP). This contrasts identical experiments on the WT enzyme where the Michaelis-like complexes have a 50-50 distribution of lid open and closed states and the oxalate-GTP complex possess only a closed lid (9). Importantly, the population of molecules in the A467G-oxalate-GTP structure that do adapt the closed conformation, demonstrate that the substitution of glycine for alanine has not changed the low energy conformation of the lid and confirms that we can interpret our kinetic data in the context of the mutation functioning by disrupting the low energy lid state and not having other structural effects (Figure 4). Unfortunately, the crystallographic studies do not allow for us to determine whether the shift in the equilibrium for the lid conformation towards the open state is due to a decrease in the closing rate or an increase in the opening rate. Previous studies with TIM have shown that hinge mutations in the Ω-loop that result in a lid with more entropic freedom do not lead to an increased rate of lid opening, but do decrease the frequency of lid closure (16). Therefore, further studies on PEPCK will be necessary in order to see what effect increasing the entropy of the lid domain has on the lid opening and closing rates.

Figure 5.

A comparison of the active sites of WT (PDB ID: 3DT2, 3DT7, 3DTB) and A467G PEPCK (PDB ID: 3MOE, 3MOF, 3MOH) in the PEPCK-Mn2+-βSP-Mn2+GTP (A: WT, B: A467G), PEPCK-Mn2+-PGA-Mn2+GDP (C: WT, D: A467G) and PEPCK-Mn2+-oxalate-Mn2+GTP (E: WT, F: A467G) complexes. All catalytic residues are rendered as ball-and-stick models colored by atom type whereas the ligands and nucleotides (βSP, PGA, oxalate, GTP, and GDP) are rendered as thick sticks colored by atom type and labeled. Potential hydrogen bonds between the ligands and the active site residues are indicated with black dashed lines. The active site and nucleotide associated manganese ions are rendered as grey spheres and the lid domain is rendered in dark red.

Kinetic consequences of the disruption of lid dynamics

Based upon the previous structural data demonstrating that PEPCK follows an induced-fit mechanism that results in the true ‘ES’ complex not being formed until the lid closes (9), we propose the schemes illustrated in figures 6 and 7, to interpret the kinetic data on the WT and A467G enzyme. We are well aware that these schemes are an oversimplification. A simple two state model would result in an equilibrium defining the open and closed lid conformations of each kinetic complex, and a more realistic interpretation would be a reaction coordinate surface that defines the ensemble of protein states in the different kinetic complexes (43, 44). However, we think the lowest energy trajectory illustrated by the simple two-dimensional reaction coordinate and the schemes is reasonable for the purpose of our interpretation of the data.

Figure 6.

Minimal kinetic schemes for the PEPCK catalyzed decarboxylation of OAA in the presence of GDP. In red is shown those steps corresponding to the different steady state kinetic complexes and constants. Eo and Ec represent the lid-open and lid-closed forms of the enzyme, respectively.

Figure 7.

Minimal kinetic schemes for the PEPCK catalyzed reaction. In the (A) OAA→PEP direction and the (B) PEP→OAA direction. In red is shown those steps corresponding to the different steady state kinetic complexes and constants. Eo and Ec represent the lid-open and lid-closed forms of the enzyme, respectively.

Lid Closure stabilizes the enolate intermediate

In the WT PEPCK-oxalate-GTP complex, Y235 is observed to occupy a rotomeric position that positions the phenolic side chain forward in the active site towards oxalate and the active site metal (9). In contrast, in molecule B of the A467G mutant structure, even though oxalate is bound at the active site, Y235 occupies a predominantly rearward rotomeric state. This state is observed as the predominant conformation for Y235 in other lid open complexes of PEPCK. The coincident nature of lid closure and the stabilization of the forward rotomer of Y235 in the presence of oxalate are supported by the structure of molecule A of the A467G mutant. Molecule A possesses a mixture of lid open and closed states and also has a mixed occupancy of the forward and rearward rotomers of Y235. While the forward rotomer of Y235 cannot directly H-bond with the enolate, the altered environment created by a shift in the lid to prefer the open state in A467G PEPCK and the resulting shift in the low energy position of Y235 appears to result in an increased Ki being observed for the A467G mutant (Table 2E). An explanation for this loss in binding energy (~ 5.3 kJ mol−1) could be that the rearward Y235 rotomer is no longer able to provide an anion-quadrapole interaction with oxalate, an interaction that has been previously suggested to be important for PEP interactions with PEPCK based upon an increased KM for PEP in Y235 mutants of human cPEPCK (29). A related observation is that in the open A467G-oxalate-GTP complex, the rearward Y235 rotomer coincides with an altered hydration state of the bound oxalate molecule (Figure 8). This altered hydration state may or may not contribute to the weakened affinity of the enzyme for the enolate/oxalate, however the change in water structure could account for the formation of pyruvate in A467G such that the repositioned water molecules create an environment where they are now able to protonate the enolate intermediate, a feature not observed in WT enzyme at 25 °C. It is presently unknown whether the enolate is protonated on the enzyme or is released and protonated in solution. However, as pyruvate only weakly associates with PEPCK (Ki = 9 mM (26)) the protonation of the tightly bound enolate would provide a mechanism for its release after protonation on the enzyme. Looking at the kinetic data, the decrease in enolate stabilization by the shift in the equilibrium position of the lid towards an open conformation and its subsequent effect on the low energy conformation for Y235 and the solvation of the active site, has the effect of increasing the activation barrier for both phosphoryl transfer and the carboxylation/decarboxylation steps (Table 2, Figure 9). The reduction in oxalate affinity, and by extrapolation, enolate affinity by a factor of ~eight translates into a reduction in the decarboxylation rate observed in the presence of OAA and GDP to approximately 57% of the WT rate and a reduction in kcat/KM for this process by over an order of magnitude (Table 2D). If, as discussed below, in the direction of OAA synthesis (Table 2B) kcat represents the phosphorylation of GDP by PEP to form the enolate intermediate, this reduction in oxalate affinity would translate into a reduction in the phosphoryl transfer rate to 5% of that for the WT enzyme (Table 2B). Interpreted in this way, the structural data on the A467G-Mn2+-oxalate-Mn2+GTP complex agree with the kinetic data. If the intermediate destabilization (~ 5.3 kJ mol−1) is fully expressed in either transition state, this would result in a reduction in catalysis by a factor of 10, a value similar in magnitude to the results of the steady-state data presented above (Table 2). It should be noted that absolute discrepancies between the oxalate affinity data and the kinetic data could be the result of not knowing the extent to which oxalate mimics the actual enolate intermediate (similar to studies on TIM (40)) and therefore the change in oxalate affinity is only a qualitative measure of potential change in enolate affinity. Further, we do not know whether the same destabilization of the enolate intermediate would be fully expressed in either/both of the two transition states. Finally, the exact nature of the rate-limiting step(s) in WT and A467G is unknown. Our interpretation does provide a reasonable explanation as to how the destabilization of the closed lid conformation leads to both a defect in catalysis and the propensity to generate pyruvate.

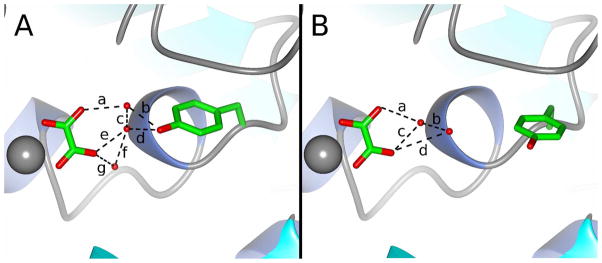

Figure 8.

Changes in the rotomeric state of Y235 and the water structure surrounding oxalate, in the A) lid-closed WT PEPCK-Mn2+-oxalate-Mn2+GTP (9) and B) lid-open A467G-Mn2+-oxalate-Mn2+GTP complexes. In A, the dashed lines represent potential hydrogen bonds with distances (a) 2.7 Å (b) 2.4 Å (c) 2.5 Å (d) 2.7 Å (e) 2.8 Å (f) 2.6 Å and (g) 3.0 Å. Similarly, in (B) the potential hydrogen bond distances are (a) 3.3 Å (b) 2.5 Å (c) 2.7 Å (d) 3.4 Å. Based upon structural work by Cotelesage et al (48), we propose that the water molecules separated by distance ‘c’ in panel A define the CO2 binding site. As illustrated in B, this binding site for CO2 is only present in the lid-closed conformation shown in A.

Figure 9.

Cartoon reaction coordinate for WT (blue solid line) and A467G (orange dashed line) PEPCK based upon the differential inhibition of the two enzyme forms by the enolate intermediate analogue, oxalate.

The above interpretation of the kinetic data also relies on kcat not being limited by the lid open/close rate in PEPCK. This would be in contrast to TIM. TIM however operates at a much higher catalytic efficiency, and the open-close transition of the phosphate ‘gripper’ loop occurs on that same time scale (~ 104 s−1) (15, 45). This rate is approximately three-orders of magnitude faster than kcat in PEPCK supporting our assumption that kcat does not represent the open/close transition in PEPCK. Further, as the effect of A467G on kcat is larger in the direction of OAA synthesis than in the direction of PEP synthesis, the asymmetry provides additional support that the phosphoryl transfer reaction is at least partially rate limiting consistent with the reaction coordinate diagram in Figure 9.

The decarboxylation of OAA

In addition to the modest change in the decarboxylation rate observed in the decarboxylation half-reaction, there is a modest increase (~eight-fold) in the KM for OAA in this reaction (Table 2D). As illustrated in Figure 6, this KM value represents both binding of OAA to the PEPCK-GDP complex, as well as the opening/closing of the lid. This conclusion is reached based upon two pieces of data:

Previous structural studies on the PEPCK-OAA-GDP complex demonstrate that this ligation state of the enzyme has an increased propensity to form the closed lid conformation, similar to the PEPCK-βSP-GTP and PEPCK-PGA-GDP Michaelis complex mimics (8).

With the rat cPEPCK, at 25 °C, the decarboxylation activity is only observed in the presence of diphosphate nucleotide.

Both of these pieces of data are consistent with the idea that lid closure is required to initiate the decarboxylation reaction. Our model for the decarboxylation activity is that, similar to formation of the Michaelis complexes, formation of the PEPCK-OAA-GDP complex results in a shift in the open-close equilibrium to the right and this leads to the generation of the enolate and CO2. However, as there is no phosphoryl donor present to phosphorylate the intermediate, pyruvate is formed and released the next time the lid samples the open conformation. Therefore, based upon the scheme illustrated in Figure 6, the observed increase in the KM value could result from either an increase in k2, kopen, or koff or a decrease in kon or kclose. As the observed reduction in k2 from the decarboxylation data is in the wrong direction to cause an increase in KM, an alternate explanation is needed. The inhibition of PEPCK by βSP suggests that kon and koff are only modestly affected, since the binding of βSP in WT and A467G differs by only a factor of approximately two. This modest effect on binding could be the result of altering lid dynamics in the PEPCK-GTP/GDP state (Figure 6) such that the altered opening and/or closing rates affect kon/koff as the structural studies demonstrate that binding of substrates to PEPCK cannot occur after lid closure (9). This type of perturbed lid behavior, prior to Michaelis complex formation, has also been used to explain the kinetic data of hinge mutations of TIM (16). Therefore, the structural and kinetic data are consistent with the observed increase in KM resulting from either a reduction in the rate of transition to the closed conformation, or an increase in the frequency of lid opening, which results in the open-close equilibrium shifting to the left resulting in an elevated KM value for OAA.

The OAA → PEP reaction

Similar to what is discussed above for the decarboxylation half-reaction, a modest reduction in kcat (26 % of WT) and an increase (14-fold) in the KM for OAA are observed. Based upon the interpretation provided above, we again conclude that the change in the KM value is due to either a decrease in the rate of lid closure or an increase in the rate of lid opening resulting in the equilibrium for the closed lid conformation shifting to the left which is consistent with both the design of the mutation and the structural data. Again, making the assumption that kcat ~ k3 (the phosphorylation of the enolate by GTP, Figure 7A), we conclude that this shift in the favorability of lid closing has a modest effect on the activation energy for the reaction as illustrated in Figure 9 and described above. The observation of the formation of pyruvate by the enzyme during turnover to PEP suggests that, while in the wild-type enzyme k3 is fast relative to kreopen (no formation of pyruvate observed), either the reduction in the phosphoryl transfer rate, through the destabilization of the enolate, or an increase in the rate of lid opening results in the rate of phosphoryl transfer becoming closer to the rate of opening, such that now for every five PEP produced one pyruvate molecule is formed (Table 2, Figure 7A). To address the possibility that a slowing of the phosphoryl transfer rate results in the observed production of pyruvate, we carried out kinetic studies on WT PEPCK using the slow substrate guanosine 5′-O-[gamma-thio]triphosphate (GTPγS). Consistent with previous studies using ITPγS (46), the use of GTPγS reduces kcat (13s−1 ) while the KM for GTPγS is 39 μM. Using GTPγS we did not observe any pyrvuate formation during the OAA→ PEP reaction. Therefore, the data suggest that making phosphoryl transfer solely/more rate limiting does not result in any decoupling of the reaction to pyruvate and that simply slowing the phosphoryl transfer rate in the absence of a destabilization of the lid-closed conformation, is not sufficient to decouple the reaction.

The PEP → OAA reaction

In contrast to the decarboxylation reaction, and the reaction in the direction of PEP formation, the reaction in the direction of OAA formation results in a reduction in the KM for PEP (~21% of the KM for WT) and a more drastic reduction in kcat (~5% of WT). Again, we can interpret the data in the context of the model presented in Figure 7B. Based upon the inhibition data using the PEP analogue PGA, we see that the decrease in the KM value with A467G is not due to solely to an increase in the affinity of the enzyme for PEP as the affinity of the enzyme for PGA increases by less than a factor of two (Table 2E). In the direction of OAA synthesis, rather than lid closure initiating decarboxylation and the formation of the enolate, in this direction (PEP → OAA) lid closure stimulates phosphoryl transfer from PEP to GDP forming the enolate intermediate since lid closure is necessary for PEP to adopt a kinetically competent conformation for phosphoryl transfer (9). Based upon the standard free energies for the reaction, we envision this to be a more energetically costly reaction (Figure 9) (6). As a consequence, the destabilization of the enolate has a more drastic effect on the activation energy barrier for the reaction in this direction, and results in kcat being reduced to 5% of the WT value. This reduction in kcat (k2) leads to the observed reduction in KM, as the observed KM value for A467G shifts in a direction toward the true KD for PEP. As the other kinetic and structural data presented here suggest that lid opening and/or closing are perturbed by the A467G mutation, the true KD for PEP should be lower than the 60 μM KM observed as the change in the position of the open-close equilibrium for the lid may still result in conditions that are not at rapid equilibrium. This interpretation is also consistent with the lack of observed pyruvate production during turnover in this reaction direction. Based again upon our free energy diagram (Figure 9), our model and data suggest that in the PEP → OAA direction the slow step, phosphoryl transfer, precedes enolate formation and therefore, if as expected, carboxylation (k3) is significantly faster than the reopening rate, this would result in the absence of pyruvate production in this direction (Figure 7B). Alternatively, the high concentrations of CO2 present in the reaction assay in this direction could result in a A467G-Mn2+-enolate-CO2-Mn2+GTP complex that alters the solvation of the enolate intermediate in much the same way as the altered rotomeric state of Y235 that coincides with the lid open enzyme does. Based upon this interpretation, even though the lid-closed conformation of PEPCK is destabilized by the A467G mutation, the water structure in the A467G-enolate-CO2-GTP complex is not conducive to enolate protonation. This model would require that the enolate complex arising from the decarboxylation of OAA rapidly looses CO2 during transition to the closed A467G-Mn2+-enolate-Mn2+GTP complex. This would be consistent with the weak affinity of the enzyme for CO2. In this direction, the resulting A467G-Mn2+-enolate-Mn2+GTP complex would possess a water structure similar to the A467G-Mn2+-oxalate-Mn2+GTP structure that we propose allows for protonation of the enolate (Figure 8B). Arguing against this latter model is the observation that when using assay conditions with sub-saturating concentrations of CO2 we are still unable to detect pyruvate formation in the PEP→OAA direction (data not shown). Based upon all of the information, we suggest it is most likely that the competing rates between phosphoryl transfer and lid re-opening result in the decoupling of the PEPCK reaction in the A467G mutation, however more work is obviously necessary to clarify the mechanism by which A467G produces pyruvate during the conversion of OAA → PEP and the lack of this activity in the opposite direction.

Conclusion

Perhaps not surprisingly, the lid domain of PEPCK has a similar general function to the lid domain found in TIM. It operates both to sequester the reactive intermediate from alternate chemistries and to stabilize the enolate intermediate. In contrast to TIM, this stabilization of the enolate by the closed lid facilitates the chemical conversion of substrates to products without the enzyme directly interacting with the substrates. The structural and kinetic characterization of A467G are consistent with the mutation causing a perturbation in the equilibrium position of the lid towards the open state consistent with the mutation increasing the conformational entropy of the domain and resulting in the decoupling of the reaction through the formation of pyruvate. In addition, this shift in the conformational equilibrium of the lid domain results in the loss of the Y235-enolate interaction which reduces the ability of the enzyme to stabilize the bound enolate and subsequently the transition states that precede and follow its formation and results in catalytic defect.

Acknowledgments

T.H. acknowledges support from National Center for Research Resources P20 RR17708. Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory, a national user facility operated by Stanford University on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Biomedical Technology Program, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

We thank Dr. Aron Fenton and Ms. Sarah Sullivan for their helpful suggestions during the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the RCSB protein databank (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb) under the accession codes 3MOE, 3MOF and 3MOH.

Abbreviations: ADP, adenosine-5′-diphosphate; ASU, asymmetric unit; βSP, 3-sulfopyruvate; cPEPCK, cytosolic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase; DTT, dithiothreitol; GDP, guanosine-5′-diphosphate; GTP, guanosine-5′-triphosphate; GTPγS, guanosine-5′-O-[gamma-thio]triphosphate; IDP, inosine-5′-di-phosphate; ITP, inosine-5′-tri-phosphate; ITPγS, inosine-5′-O-[gamma-thio]triphosphate NCS, non-crystallographic symmetry; OAA, oxaloacetic acid; PEG, polyethylene glycol; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; PEPCK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase; PGA, 2-phosphoglycolate; RMSD, root-mean-square-deviation; TIM, triosephosphate isomerase; TLS, translation/libration/screw.

In our hands, βSP is observed to act as a mixed inhibitor of PEPCK against OAA that we have identified is due to contamination of our βSP preparations with low levels of chloride. Structural studies of the PEPCK-βSP complex demonstrate that this results in weak binding of chloride near the active site of PEPCK and leads to the observed mixed inhibition pattern (Johnson and Holyoak, unpublished data). For the purposes of this study we only report the Ki values on the slope representing the competitive binding of βSP to the OAA site of PEPCK.

References

- 1.Lee MH, Hebda CA, Nowak T. The Role of Cations in Avian Liver Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase Catalysis. Activation and Regulation. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:12793–12801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colombo G, Carlson GM, Lardy HA. Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase (Guanosine 5′-Triphosphate) from Rat Liver Cytosol. Dual-Cation Requirement for the Carboxylation Reaction. Biochemistry. 1981;20:2749–2757. doi: 10.1021/bi00513a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hebda CA, Nowak T. The Purification, Characterization, and Activation of Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase from Chicken Liver Mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:5503–5514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hebda CA, Nowak T. Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase. Mn2+ and Mn2+ Substrate Complexes. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:5515–5522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang J, Kalhan SC, Hanson RW. What Is the Metabolic Role of Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase? J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27025–27029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.040543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlson GM, Holyoak T. Structural Insights into the Mechanism of Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase Catalysis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:27037–27041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.040568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stiffin RM, Sullivan SM, Carlson GM, Holyoak T. Differential Inhibition of Cytosolic Pepck by Substrate Analogues. Kinetic and Structural Characterization of Inhibitor Recognition. Biochemistry. 2008;47:2099–2109. doi: 10.1021/bi7020662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan SM, Holyoak T. Structures of Rat Cytosolic Pepck: Insight into the Mechanism of Phosphorylation and Decarboxylation of Oxaloacetic Acid. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10078–10088. doi: 10.1021/bi701038x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan SM, Holyoak T. Enzymes with Lid-Gated Active Sites Must Operate by an Induced Fit Mechanism Instead of Conformational Selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13829–13834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805364105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alber T, Banner DW, Bloomer AC, Petsko GA, Phillips D, Rivers PS, Wilson IA. On the Three-Dimensional Structure and Catalytic Mechanism of Triose Phosphate Isomerase. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1981;293:159–171. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1981.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banner DW, Bloomer AC, Petsko GA, Phillips DC, Pogson CI, Wilson IA, Corran PH, Furth AJ, Milman JD, Offord RE, Priddle JD, Waley SG. Structure of Chicken Muscle Triose Phosphate Isomerase Determined Crystallographically at 2.5 Angstrom Resolution Using Amino Acid Sequence Data. Nature. 1975;255:609–614. doi: 10.1038/255609a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lolis E, Petsko GA. Crystallographic Analysis of the Complex between Triosephosphate Isomerase and 2-Phosphoglycolate at 2.5-a Resolution: Implications for Catalysis. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6619–6625. doi: 10.1021/bi00480a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joseph D, Petsko GA, Karplus M. Anatomy of a Conformational Change: Hinged “Lid” Motion of the Triosephosphate Isomerase Loop. Science. 1990;249:1425–1428. doi: 10.1126/science.2402636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fersht AR. Catalysis, Binding and Enzyme-Substrate Complementarity. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1974;187:397–407. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1974.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams JC, McDermott AE. Dynamics of the Flexible Loop of Triosephosphate Isomerase: The Loop Motion Is Not Ligand Gated. Biochemistry. 1995;34:8309–8319. doi: 10.1021/bi00026a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kempf JG, Jung JY, Ragain C, Sampson NS, Loria JP. Dynamic Requirements for a Functional Protein Hinge. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:131–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffith OW, Weinstein CL. Beta-Sulfopyruvate. Methods Enzymol. 1987;143:221–223. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)43040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colombo G, Carlson GM, Lardy HA. Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase (Guanosine Triphosphate) from Rat Liver Cytosol. Separation of Homogeneous Forms of the Enzyme with High and Low Activity by Chromatography on Agarose-Hexane-Guanosine Triphosphate. Biochemistry. 1978;17:5321–5329. doi: 10.1021/bi00618a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-Ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. Molrep: An Automated Program for Molecular Replacement. J Appl Cryst. 1997;30:1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bailey S. The Ccp4 Suite - Programs for Protein Crystallography. Acta Cryst. 1994;D50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-Building Tools for Molecular Graphics. Acta Cryst. 2004;D60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Painter J, Merritt EA. A Molecular Viewer for the Analysis of Tls Rigid-Body Motion in Macromolecules. Acta Cryst. 2005;D61:465–471. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905001897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Painter J, Merritt EA. Optimal Description of a Protein Structure in Terms of Multiple Groups Undergoing Tls Motion. Acta Crystallographica Section D-Biological Crystallography. 2006;62:439–450. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Painter J, Merritt EA. Tlsmd Web Server for the Generation of Multi-Group Tls Models. J Appl Crystallogr. 2006;39:109–111. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ash DE, Emig FA, Chowdhury SA, Satoh Y, Schramm VL. Mammalian and Avian Liver Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase - Alternate Substrates and Inhibition by Analogs of Oxaloacetate. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:7377–7384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noce PS, Utter MF. Decarboxylation of Oxalacetate to Pyruvate by Purified Avian Liver Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:9099–9105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holyoak T, Nowak T. Ph Dependence of the Reaction Catalyzed by Avian Mitochondrial Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7054–7065. doi: 10.1021/bi049707e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dharmarajan L, Case CL, Dunten P, Mukhopadhyay B. Tyr235 of Human Cytosolic Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase Influences Catalysis through an Anion-Quadrupole Interaction with Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxylate. FEBS J. 2008;275:5810–5819. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jabalquinto AM, Laivenieks M, Zeikus JG, Cardemil E. Characterization of the Oxaloacetate Decarboxylase and Pyruvate Kinase-Like Activities of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae and Anaerobiospirillum Succiniciproducens Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinases. J Protein Chem. 1999;18:659–664. doi: 10.1023/a:1020602222808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunten P, Belunis C, Crowther R, Hollfelder K, Kammlott U, Levin W, Michel H, Ramsey GB, Swain A, Weber D, Wertheimer SJ. Crystal Structure of Human Cytosolic Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase Reveals a New Gtp-Binding Site. J Mol Biol. 2002;316:257–264. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiang J, Jung JY, Sampson NS. Entropy Effects on Protein Hinges: The Reaction Catalyzed by Triosephosphate Isomerase. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11436–11445. doi: 10.1021/bi049208d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor JC, Markham GD. Conformational Dynamics of the Active Site Loop of S-Adenosylmethionine Synthetase Illuminated by Site-Directed Spin Labeling. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;415:164–171. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hedstrom L, Szilagyi L, Rutter WJ. Converting Trypsin to Chymotrypsin: The Role of Surface Loops. Science. 1992;255:1249–1253. doi: 10.1126/science.1546324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson TA, Qiu J, Plaut AG, Holyoak T. Active-Site Gating Regulates Substrate Selectivity in a Chymotrypsin-Like Serine Protease the Structure of Haemophilus Influenzae Immunoglobulin A1 Protease. J Mol Biol. 2009;389:559–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perona JJ, Craik CS. Evolutionary Divergence of Substrate Specificity within the Chymotrypsin-Like Serine Protease Fold. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:29987–29990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.29987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watt ED, Shimada H, Kovrigin EL, Loria JP. The Mechanism of Rate-Limiting Motions in Enzyme Function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11981–11986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702551104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sampson NS, Knowles JR. Segmental Motion in Catalysis: Investigation of a Hydrogen Bond Critical for Loop Closure in the Reaction of Triosephosphate Isomerase. Biochemistry. 1992;31:8488–8494. doi: 10.1021/bi00151a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sampson NS, Knowles JR. Segmental Movement: Definition of the Structural Requirements for Loop Closure in Catalysis by Triosephosphate Isomerase. Biochemistry. 1992;31:8482–8487. doi: 10.1021/bi00151a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pompliano DL, Peyman A, Knowles JR. Stabilization of a Reaction Intermediate as a Catalytic Device: Definition of the Functional Role of the Flexible Loop in Triosephosphate Isomerase. Biochemistry. 1990;29:3186–3194. doi: 10.1021/bi00465a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fisher HF. A Unifying Model of the Thermodynamics of Formation of Dehydrogenase-Ligand Complexes. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1988;61:1–46. doi: 10.1002/9780470123072.ch1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jencks WP. Binding Energy, Specificity, and Enzymic Catalysis: The Circe Effect. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1975;43:219–410. doi: 10.1002/9780470122884.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swint-Kruse L, Fisher HF. Enzymatic Reaction Sequences as Coupled Multiple Traces on a Multidimensional Landscape. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benkovic SJ, Hammes GG, Hammes-Schiffer S. Free-Energy Landscape of Enzyme Catalysis. Biochemistry. 2008;47:3317–3321. doi: 10.1021/bi800049z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rozovsky S, Jogl G, Tong L, McDermott AE. Solution-State Nmr Investigations of Triosephosphate Isomerase Active Site Loop Motion: Ligand Release in Relation to Active Site Loop Dynamics. J Mol Biol. 2001;310:271–280. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Konopka JM, Lardy HA, Frey PA. Stereochemical Course of Thiophosphoryl Transfer Catalyzed by Cytosolic Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase. Biochemistry. 1986;25:5571–5575. doi: 10.1021/bi00367a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Potterton L, McNicholas S, Krissinel E, Gruber J, Cowtan K, Emsley P, Murshudov GN, Cohen S, Perrakis A, Noble M. Developments in the Ccp4 Molecular-Graphics Project. Acta Crystallographica Section D-Biological Crystallography. 2004;60:2288–2294. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904023716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cotelesage JJH, Puttick J, Goldie H, Rajabi B, Novakovski B, Delbaere LTJ. How Does an Enzyme Recognize Co2? International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2007;39:1204–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]