Abstract

A third signal that can be provided by IL-12 or Type I IFN is required for differentiation of naïve CD8 T cells responding to Ag and costimulation. The cytokines program development of function and memory within three days of initial stimulation, and we show here that programming involves regulation of a common set of about 355 genes including T-bet and eomesodermin. Much of the gene regulation program is initiated in response to antigen and costimulation within twenty-four hours, but is then extinguished unless a cytokine signal is available. Histone deacetylase inhibitors mimic the effects of IL-12 or Type I IFN signaling, indicating that the cytokines act to relieve repression and allow continued gene expression by promoting increased histone acetylation. In support of this, increased association of acetylated histones with the promoter loci of granzyme B and eomesodermin is shown to occur in response to IL-12, IFNα or histone deacetylase inhibitors. Thus, IL-12 and IFNα/β enforce in common a complex gene regulation program that involves, at least in part, chromatin remodeling to allow sustained expression of a large number of genes critical for CD8 T cell function and memory.

Keywords: T cell, cytotoxic; Cytokines; Gene regulation, Cell differentiation

INTRODUCTION

Naïve CD8 T cells that encounter antigen (Ag) on mature dendritic cells (DCs) proliferate, clonally expand, and differentiate to acquire effector functions and altered adhesion-migration properties that facilitate trafficking to peripheral tissues (1, 2). Many of the effector cells then die, but about ten percent persist long-term as memory cells that respond rapidly upon re-encountering Ag. In contrast, Ag presentation by immature DC results in normal CD8 T cell proliferation, but clonal expansion is limited by poor survival, effector functions are compromised, and tolerance results. Although Ag and costimulatory ligands, usually B7-1 and 2, are essential for the activation and proliferation of naïve cells, there is now considerable evidence that these two signals are not sufficient to promote survival, differentiation and establishment of memory. Instead, a third signal is required that can be provided by either IL-12 or IFNα/β (3-9).

The requirement for a third signal was initially demonstrated in vitro using highly purified naïve CD8 T cells and artificial Ag presenting cells (aAPC); microspheres with class I/peptide Ag complexes and B7-1 ligands on the surface (5, 6, 10). Consistent with these in vitro results, co-administration of peptide Ag with IL-12 (11) or IFNα (7) bypassed the requirement for adjuvant to generate strong in vivo responses, and avoided the tolerance induced when peptide alone was administered. The relative contributions of IL-12 and IFNα/β in vivo depend upon the physiologic response being examined. In an ectopic heart transplant model it was shown that CD4 T cells ‘conditioned’ DCs to produce IL-12 and that this IL-12 was necessary to support development of CD8 effector functions and graft rejection (12). In contrast, the response to LCMV infection was reduced by greater than ninety-nine percent when the virus-specific CD8 T cells lacked the receptor for Type I IFNs (7), while the response to vaccinia virus (VV)2 infection was only partially reduced (3). Both IL-12 and Type I IFNs support CD8 T cell responses to Listeria monocytogenes (LM) and VV infections (13). For both LM and VV expressing the OVA257-264 peptide Ag, OT-I CD8 T cells that lacked both IL-12 and Type I IFN receptors undergo strong primary clonal expansion, but function is compromised at the peak of the response and a memory population does not form. Similarly, the weak CD8 T cell response that occurs to E.G7 thymoma tumor depends upon IL-12 and/or Type I IFN (14). Thus, IL-12 and Type I IFNs appear to be the major sources of the third signal for CD8 T cell activation in normal mice.

Interaction of naïve CD8 T cells with Ag and B7-1 for a few hours is sufficient to program the cells to subsequently undergo multiple rounds of division over the next three days (15), but survival is poor and effector functions do not develop in the absence of IL-12 or IFNα/β signals (15, 16). Optimal clonal expansion and development of function requires stimulation with Ag, B7-1 and IL-12 for a prolonged period (16), consistent with the prolonged interaction that occurs between CD8 T cells and DC in lymph nodes under conditions that lead to effective activation (17, 18). The programming required for development of a memory population also occurs as a result of signals received while the cells are initially responding to Ag. In vitro stimulation of splenocytes for three days is sufficient to yield a memory population when the cells are then transferred into normal mice (19). When naïve cells are stimulated for 3 days with Ag and B7-1 on aAPC and transferred into normal mice, very few of the cells survive to day 30 and those that do are tolerant, while cells stimulated with aAPC and IL-12 for three days form a protective memory population upon transfer (13). Thus, during the first three days of a response to Ag and costimulation, IL-12 not only signals for development of effector functions, they program the cells to survive as functional memory cells.

To determine the extent and molecular nature of the differentiation program induced by IL-12 and IFNα/β in concert with TCR and CD28 signals, we have carried out oligonucleotide microarray analysis of naïve cells responding to Ag and B7-1 alone, and in the presence of IL-12 or IFNα. The results demonstrate that the differentiation program induced by the cytokines includes changes in expression of many genes that have important roles in CD8 T cell survival, function, signaling, and migration, as well as of genes for transcription factors that are likely to have important roles in controlling these expression patterns, including T-bet and Eomes. The temporal pattern of IL-12/IFNα/β - regulated gene expression suggests that histone-dependent chromatin remodeling mechanisms play a central role in determining the differentiation program, and evidence in support of this is presented.

Materials and Methods

Mice and In Vitro Cell Stimulation

Naïve (CD44lo) CD8+ T cells from lymph nodes of OT-1 mice, having a transgenic TCR specific for H-2Kb/Ova257-264 (20), were negatively enriched (MACS, Miltenyi Biotec) to >97% purity. Artificial APC (aAPC) were made using 5μM latex microspheres coated with Dimer-X-H-2Kb:Ig fusion protein (BD Pharmingen; 2.5ug/107 beads) and B7-1/Fc chimeric protein (R&D Systems; 0.15ug/107 beads) and Ag complexes formed using 200nM OVA257-264 peptide. Cells were cultured in vitro at 1:4 ratio with the aAPC in absence or presence of murine rIL-12 (Genetics Institute; 2U/ml) or Universal Type I IFN (PBL Biomedical Laboratories; 1000U/ml). All cultures were supplemented with human rIL-2 at 2.5 U/ml (TECIN: NCI Biological Resources Branch). Trichostatin A (Upstate Biotechnology; 7.5ng/ml), sodium butyrate (Sigma-Aldrich; 1mM) and curcumin (Sigma-Aldrich; 2-5ug/ml) were added from the beginning of the cell culture when used. In presence of TSA, cells exhibited good viability but proliferation at 72 hr was reduced. Cells were harvested at the indicated times for staining, and total RNA was isolated (RNeasy Mini Kit, Qiagen) for cRNA preparation for hybridization onto GeneChip or for cDNA preparation for semi-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Mice were housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions at the University of Minnesota, and were used in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines and with the approval of the Institutional Care and Use Committee of the University of Minnesota.

Intracellular staining and In vitro Cytolytic Assay

Cells were harvested at indicated times, with addition of 0.6ul/ml GolgiStop (BD Pharmingen) for last 3-h of culture, and intracellular staining performed as previously described (4) using PE conjugated anti-human grzB and mouse IgG1 (Caltag Lab), APC conjugated anti-IFNγ and rat IgG1 (eBioscience) antibodies, and analyzed by flow cytometry using FLOWJO software. For T-bet intranuclear detection, fixed cells were permeabilzed with 0.12% Triton X and 2% FCS in PBS and stained for 2 h with fluorescein isothiocynate-conjugated mouse anti-T-bet mAb (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Cytolytic activity was determined in a standard 4-h 51Cr release assay using E.G7 cells (EL-4 thymoma transfected with OVA) as targets with EL-4 cells included as a control for specificity. Triplicate measurements were done in all assays with SD<0.05%.

cRNA preparation and Microarray Data Analysis

Biotin-labeled transcripts were prepared from 10ug of RNA according to the manufacturer's protocol for hybridization onto Affymetrix MG U74Av2. The quality of cRNA was evaluated using test chips. GeneChips were probed, hybridized and scanned at the University of Minnesota Biomedical Genomics Center Facility. Triplicate arrays were done for naïve (0h) and three-signals stimulated cells (48h) and four arrays for two-signal stimulated (48h) RNA samples obtained from independent experiments and single arrays were done for 24- and 72h samples. For triplicate samples, transcripts were included in the analysis if ‘present’ in two out of three experiments and for Ag-B7 (48h) if ‘present’ in at least two experiments. Signal log ratios were generated between comparing samples (MAS 5.0 comparison analysis) and fold change calculated as = 2^signal log ratios. Significant differentially expressed genes were sorted that expressed an average fold change ≥1.70 and change p-value ≤0.05 (Wilcoxon's Signed Rank test). Gene treeview clustering, hierarchical linkage and K-mean clustering was performed using GeneSpring software version 7.2 (Agilent Technologies). The microarray data has been deposited in the NCBI GEO database and can be accessed at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE15930.

Semi-quantitative Reverse Transcriptase-PCR

Total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using Superscript RNAseH-(III) (Invitrogen). 75ng cDNA was amplified using PCR setting (94°C/5min; 94°C/30s, 60-65°C/60s, 72°C/60s, 72°C/10min; 27 cycles-Tbet /Eomes; 21 cycles-β-actin) with primers sequences designed using Primer3 software as follows: T-bet (575bp), 5’-cag gat gtt tgt gga tgt gg-3’ and 5’-ctg gaa ggt cgg ggt aga a-3’; eomesodermin (642bp), 5’-gtg gcg ctt atc aga gga ag-3’ and 5’-ggc act cgt tct tca tag cc-3’; β-actin (224bp), 5’-cca ggt cat cac tat tgg caa cga-3’ and 5’-gag cag taa tct cct tct gca tcc-3’. Amplification was done for 20, 22, 25, 27 and 30 cycles to determine the linear range of amplification for t-bet and eomes mRNA. β-actin expression was found same in all samples at 15, 17 and 21 cycles.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay and quantitative real-time PCR

Purified naïve CD8 T cells stimulated in vitro as described above were harvested at 48h to obtain ~15 × 106 cells that were processed for CHIP assay and real-time PCR using a described procedure (21). Anti-acetyl H3 and anti-acetyl H4 (Upstate Biotechnology) antibodies were used with normal rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz) as isotype controls. The primer pairs used for analysis of DNA were: grzb promoter (292bp): fwd 5’-act aga tgg tca tgc ttg gtc ctg-3’, rev 5’-tat gaa aac tcc tgc cct act gcc-3’; grzb distal (248bp): 5’-ggc cca caa cat caa aga aca gga-3’, rev 5’-tgt tgg gga aga agc aag agt cca-3’; eomes promoter (149bp): fwd 5’-gcc aat agc aaa gtc ccc ta-3’, rev 5’-tag caa cca gcc att tcc tc-3’. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on Cepheid SmartCycler II system with a cycle of 95°C, 5min; 95°C, 15s; 62 (eomes) / 65 (grzB) °C, 30s; 72°C 30s for 40 cycles. Template copy numbers for PCR cycle thresholds were extracted using standard graphs. For each sample, template copy numbers were internally normalized with their respective input control. Relative Expression was calculated as ratio of template copy numbers of a sample relative to the naïve control after normalizing with their respective isotype control IgG and is shown as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by a one-tail paired Student's t test.

Online Supplementary Material

Table S1 provides a list of genes regulated by two-signals (Ag-B7) at 24, 48 and 72 h compared with naïve (0 h) CD8 T cells; Table SII lists IL-12 dependent gene expression changes with respect to Ag-B7; Table SIII shows IFNα mediated changes in gene expression with respect to Ag-B7; Table SIV lists genes regulated in common by IL-12 and IFNα (from Tables SII and SIII); Figures S1 and S2 depict various kinetic patterns of gene regulation in response to IL-12 and IFNα respectively as determined using the K-mean clustering algorithm; Tables SV and SVI provide lists of genes as illustrated in Figures S1 and S2 respectively; Table SVII shows genes regulated by trichostatin A in common with IL-12 and IFNα.

RESULTS

Gene expression regulation in response to Ag and B7-1 alone (two signals) or with IL-12 or IFNα (three signals)

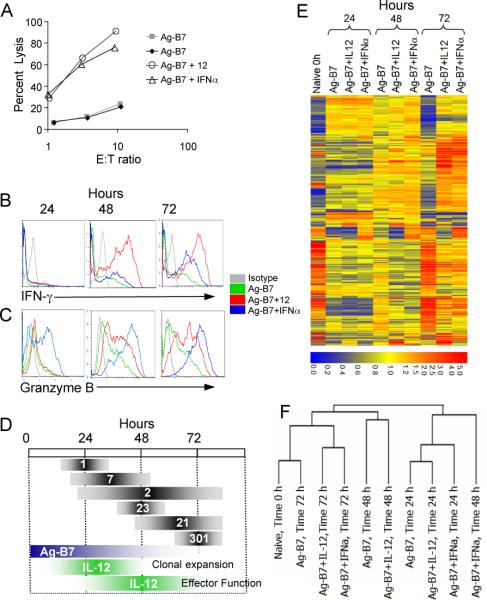

When naïve (CD44lo) OT-I CD8 T cells expressing a transgenic TCR specific for H-2Kb and OVA257-264 peptide (20) are stimulated with microspheres coated with H-2Kb/OVA257-264 complex and B7-1 ligand (Ag-B7) the cells proliferate and clonally expand. However, they fail to become cytolytic effectors (Fig. 1A), express low Granzyme B (grzB) levels (Fig. 1B), and produce little IFNγ upon re-stimulation (Fig. 1C) unless IL-12 or Type I IFN are also present in the cultures. Use of aAPC and purified naïve TCR transgenic CD8 T cells provides an ideal system for determining the contributions of cytokines to gene regulation and differentiation. The signals available to the cells are precisely defined since unlike APC, the aAPC do not display additional ligands or produce other cytokines, and they do not contribute to the pool of RNA isolated for analysis. In these experiments, IL-2 was added to all of the cultures to achieve maximum clonal expansion and avoid gene expression changes due to transient secretion of this cytokine by the activated T cells.

Figure 1. Programming of CD8 T cell differentiation requires IL-12 and/or IFNα along with Ag and costimulation.

(A) Purified naïve (CD44lo) OT-1 CD8 T cells were stimulated for 3 days in vitro with aAPC coated with H-2Kb / Ova257-264 peptide and B7-1 either alone, or with IL-12 or IFNα. All cultures were supplemented with IL-2. Cytolytic activity was measured on day 3 by 51Cr release assay using E.G7 target cells.

(B-C) Cells stimulated as in (A) were analyzed by intracellular staining on days 1, 2 and 3 for expression of IFNγ and grzB.

(D) The upper bars (gray) show the numbers of genes regulated in common by IL-12 and IFNα at 24, 48 and 72h. The lower bars (colored) show the times during which Ag-B7 and IL-12 must be present for optimal clonal expansion and development of effector function (from ref. (16)).

(E) Expression patterns for 408 probe ids representing the 375 genes regulated by both IL-12 and IFNα. The stimuli used and time in culture for each sample are shown at the top. Red represents high expression (signal value) and blue represents low expression on a log2 scale of 6.0 to 0.0 as shown at the bottom. Data not meeting the selection criterion was excluded and appears gray. The signal value was normalized to around 1.

(F) Hierarchical clustering linkage for cells treated with the various stimuli at 0, 24, 48 and 72h.

Gene expression was analyzed using Affymetrix murine MG U74Av2 gene chips displaying 12,488 genes/ESTs. Naïve OT-1 CD8 T cells expressed 4,273 transcripts in at least two out of three independent experiments, based on the criteria that the mRNA was ‘present’ with p < 0.05. Clonal expansion and differentiation of naïve CD8 T cells occurs over 3 days, and Ag-B7 and IL-12 or IFNα/β must be present for most of this period to achieve maximal responses (16). We therefore analyzed gene expression at 24, 48 and 72h and restricted our analysis to genes showing a fold change of ≥ 1.70 (p ≤ 0.05) in expression between stimulation conditions. Compared to naïve cells, stimulation with Ag-B7 resulted in up- or down-regulation of a large set of genes/ESTs at all time points (Table I), with the largest number being at 24h. Ag and B7-1 are sufficient to stimulate multiple rounds of cell division (15, 16) and, not surprisingly, expression of genes involved in cell cycle control, DNA synthesis and repair, and protein translation were coordinately regulated by these two signals (Table SI: Ag-B7 versus Naïve).

Table I.

Numbers of genes regulated by IL-12 and IFNα

| Hours | Ag-B71 vs. Naïve | IL-12+Ag-B72 vs. Ag-B7 | IFNα+Ag-B72 vs. Ag-B7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | ~3,500 | 83 | 64 |

| 48 | ~3,000 | 213 | 112 |

| 72 | ~2,300 | 730 | 610 |

The total number of genes with increased or decreased expression at 24, 48 or 72 hr by a fold change ≥ 1.70 in response to Ag and B7-1 relative to expression in naïve cells.

The number of genes that increased or decreased in expression at 24, 48 or 72 hr by ≥ 1.7-fold in response to Ag-B7 and IL-12 or IFNα relative to cells stimulated with only Ag-B7.

When compared to expression in cells stimulated with only Ag-B7, addition of IL-12 or IFNα was found to further regulate expression of a modest number of genes/ESTs (Table I). In contrast to Ag-B7 stimulation, where the greatest number of genes was regulated at 24h, the numbers of genes regulated in response to IL-12 and IFNα/β progressively increased at longer times. Since the functional outcome of signaling via IL-12 or IFNα is similar, the genes regulated in common by both cytokines were of greatest interest. This set included 355 genes commonly regulated at least one time point. Previous work showed that prolonged signaling by Ag-B7 and IL-12 are necessary for full activation, and defined temporal windows required for IL-12 to optimally support clonal expansion (15-35 hrs) and development of effector functions (30-60 hrs) (16). This is depicted in Figure 1D, along with the numbers of genes regulated in common by IL-12 and IFNα at these times. Distinct patterns of regulation are seen, with the majority of genes being regulated late, during the period when IL-12 signaling is critical for development of effector functions.

Expression levels of the set of genes regulated in common by IL-12 and IFNα are shown in Figure 1E. In comparison to naïve cells, expression of the majority of these genes changes within 24h in response to Ag-B7, and most exhibit similar expression levels whether or not IL-12 or IFNα/β are present. By 72h, however, expression levels of most of these genes in cells stimulated with Ag-B7 revert to a pattern quite similar to that of naïve cells, and very distinct from the patterns observed in cells stimulated with IL-12 or IFNα. Hierarchical clustering (Fig. 1F) confirmed that at 72h the expression levels of genes in cells stimulated with Ag-B7 were most closely linked to those of naïve cells, while the 72h expression profiles of cells stimulated in the presence of IL-12 or IFNα were closely linked to each other. The expression profiles for cells stimulated with IL-12 and IFNα for 72h reveals striking similarities, but there are also differences, including genes whose expression is changed in opposite directions by the two cytokines. For many of the genes regulated by both IL-12 and IFNα, it appears that signals provided by Ag-B7 initiate changes in expression levels within 24h, but the changes are transient and expression reverts to naïve levels by 72h. In the presence of either IL-12 or IFNα/β, the changes in expression increase and persist at 72h and additional changes occur, consistent with these cytokines inducing a differentiation program in the cells.

Genes regulated by IL-12/IFNα/β and patterns of temporal expression

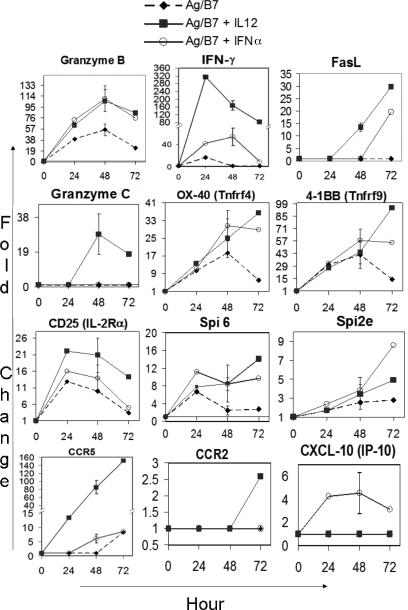

Complete data sets at 24, 48 and 72h for genes that change in expression level in cells stimulated with Ag-B7 in comparison to naïve cells, and for genes that change in response to IL-12 and IFNα in comparison to Ag-B7 alone, are included as Supplementary Tables SI-III. Table SIV lists the subset of these genes that are regulated in common by IL-12 and IFNα. Gene regulation in response to only Ag-B7 is briefly described in the discussion. A partial listing of the genes regulated by IL-12 and IFNα is shown in Figure 2 and Table II. Analysis based on biological function (NCBI database, GenBank annotation and literature search) demonstrates that IL-12 and IFNα/β regulate expression of numerous genes that encode proteins for CTL effector functions, cell surface receptors, signal transduction, defense and homeostasis, transcription regulation, cell adhesion and migration, cytoskeleton, secretion, metabolism, transport, and other functions (Table II and Tables SII-IV). Some of these are of obvious relevance for acquisition of effector functions, including grzB, Fas ligand and IFNγ. Others are known, or are likely to be, important in conferring the ability to survive (and thus undergo clonal expansion) and regulate migration to peripheral tissues. Time courses for expression of a number of genes in response to two or three signals are shown in Figure 2 (note that these are not included in Table II to avoid duplication), and illustrate several ways in which IL-12 and IFNα regulate expression. For several, including grzB, IFNγ, OX-40, 4-1BB and serine protease inhibitor 6, Ag-B7 upregulates expression by 24h but levels then decline, while IL-12 and IFNα act to enhance and sustain the expression. Numerous other genes are regulated in a similar fashion, as illustrated in Figure 1E. Other genes, including CD25 and Spi2e, are upregulated in response to Ag-B7 and further increased in response to either IL-12 or IFNα. Still others do not change expression in response to Ag-B7, but are upregulated in response to IL-12 (grzC and grzF, CCR5, CCR2), IFNα (CXCL-10, ISG-15) or both (FasL). The expression levels of a few genes (including IFN-regulated genes, calcyclin and Schlafen genes) are inversely regulated in the presence of IL-12 or IFNα. A more complete description of the different temporal patterns of regulation for groups of genes is included in Figures S1-2 and Tables SV-VI.

Figure 2. IL-12 and IFNα induce, enhance or sustain the expression of genes involved in effector functions.

Time courses for expression of selected genes regulated by IL-12 and IFNα are shown. Expression is shown as the fold change in signal intensities upon stimulation with Ag-B7 alone ( ) or with IL-12 (ν) or IFNα (○) compared to the signal intensity for the gene in naïve cells (0 hr). (Note: different scales are used on y-axis for each gene, and scale breaks are included on the y-axis for IFNγ and CCR5).

) or with IL-12 (ν) or IFNα (○) compared to the signal intensity for the gene in naïve cells (0 hr). (Note: different scales are used on y-axis for each gene, and scale breaks are included on the y-axis for IFNγ and CCR5).

Table II.

Changes in gene expression in response to Ag-B7 alone and with IL-12 or IFNα.1

| FOLD CHANGE | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| | |||||||||||

| | |||||||||||

| Gene | Accession Number | 24h | 48h | 72h | 24h | 48h | 72h | 24h | 48h | 72h | 72h |

| Cell surface receptor & signal transduction | |||||||||||

| IL-12Rβ1 | U23922 | 4.6 | 2.6 | * | * | * | 2.5 | * | * | 1.7 | 1.9 |

| IL-12Rβ2 | U64199 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 8.2 | 1.8 | 3.7 | 3.5 | * | 1.7 | 2.1 | * |

| IL-7R | M29697 | -29.6 | -14.6 | -1.8 | * | 2.8 | 1.7 | * | * | * | -3.7 |

| IL-15Rα | U22339 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 1.7 | 1.8 | * |

| IL-10Rα | L12120 | * | * | * | * | * | 1.7 | * | 3.6 | 4.0 | 2.1 |

| Tnfsf4 (OX-40L) | U12763 | * | * | * | 2.6 | * | 11.1 | 2.5 | * | * | * |

| Tnfrsf18 (GITR) | U82534 | * | 2.2 | * | * | * | 2.8 | * | * | 1.8 | * |

| Tnfrsf7 (CD27) | L24492 | * | * | 3.8 | * | * | -1.7 | * | * | -1.7 | -2.8 |

| Gadd45γ | AF055638 | * | * | * | 3.7 | 5.4 | 3.2 | * | * | * | 5.6 |

| Gadd45β | AV138783 | 2.5 | -2.4 | -3.8 | * | 2.5 | 2.6 | * | 4.4 | * | 2.3 |

| TRAF4 | AV109962 | * | * | * | * | 1.7 | 2.8 | * | * | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| TRAF6 | D84655 | * | * | * | * | * | 1.8 | * | * | * | 1.9 |

| Cytotoxic function and cytokines (see also Figure 2) | |||||||||||

| TRAIL / Apo2L | U37522 | * | * | * | 2.0 | 2.4 | * | * | * | * | * |

| Granzyme F | J03257 | * | * | * | 5.2 | 7.5 | * | * | * | * | |

| TNF-α | U16985 | -3.3 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 9.2 |

| VEGF-A | M95200 | 5.9 | 9.2 | * | * | 2.4 | 7.5 | * | * | 5.7 | -3.5 |

| Cell adhesion and migration | |||||||||||

| CD44 | X66084 | 9.5 | 8.4 | 8.2 | * | * | * | * | * | * | -2.1 |

| CCR7 | L31580 | -5.9 | -3.6 | -2.1 | * | -2.4 | * | * | * | * | -1.9 |

| CXCR3 | AF045146 | * | 2.2 | 3.9 | * | -2.5 | -3.5 | * | * | -2.1 | * |

| Mac-2/Galectin-3 | X16834 | 21.4 | 72.5 | 168 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 3.0 | * | * | * | -7.5 |

| L-selectin (CD62L) | M36058 | -8.9 | -3.2 | * | * | * | -3.0 | * | * | -2.3 | -2.6 |

| CCL9 | U49513 | 2.3 | * | * | 1.7 | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| CCL3 (MIP-1α) | J04491 | 12.2 | 11.8 | * | * | * | 2.5 | * | * | * | 8.6 |

| CCL4 (MIP-1β) | X62502 | 39.0 | 21.2 | 1.9 | * | * | 2.8 | * | * | * | 8.6 |

| XCL-1 | U15607 | 21.4 | 12.2 | 6.4 | * | * | 1.7 | * | * | 2.1 | 5.3 |

| Integrin β7 | M68903 | -4.9 | -2.8 | * | * | -2.2 | -1.7 | * | -1.9 | -2.3 | -3.7 |

| Galectin-9 ligand | U55060 | -2.4 | * | * | * | * | -2.0 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 1.8 | * |

| Rho GDI-γ | U73198 | 6.7 | 6.1 | * | * | * | 4.6 | * | * | 9.2 | * |

| Defense and homeostasis | |||||||||||

| Glycoprotein 49 A | M65027 | -1.5 | 2.6 | * | 7.5 | 12.0 | 9.2 | * | * | * | * |

| Glycoprotein 49 B | U05265 | -3.6 | * | * | 6.5 | 16.5 | 4.6 | * | * | * | * |

| CTLA 2 alpha | X15591 | -5.8 | * | 6.6 | 2.5 | 8.5 | 3.7 | * | * | * | * |

| CTLA 2 beta | X15592 | * | * | 9.7 | * | 23.8 | 3.7 | * | * | * | -3.7 |

| Transcription regulation | |||||||||||

| Bhlhd-B2 | Y07836 | 8.7 | 14.8 | 4.8 | * | 3.0 | 9.2 | * | * | 5.6 | * |

| Prdm-1 (BLIMP-1) | U08185 | * | * | -1.9 | * | 3.0 | 7.5 | 1.7 | 2.8 | * | |

| Eomesodermin | AW120579 | -2.2 | -1.9 | -2.9 | * | * | * | 4.0 | 11.2 | 4.0 | 13.9 |

| NF-IL3R | U83148 | * | * | * | * | * | 6.5 | * | * | 2.5 | * |

| LKLF 2 | U25096 | -154 | -16.8 | -4.1 | * | * | 19.7 | * | * | -3.2 | -22.6 |

| LEF-1 | D16503 | * | * | * | * | * | -2.0 | * | * | -2.1 | -2.3 |

| Gata binding protein 3 | X55123 | -3.2 | * | 1.8 | -2.8 | -3.9 | -4.6 | * | * | -2.3 | -1.7 |

| TCF-7 | AI019193 | -4.1 | -3.7 | * | * | -4.0 | -8.0 | * | -1.8 | -2.6 | * |

| TGFβ inducible egr | AF064088 | * | * | 3.3 | * | -2.9 | -17.2 | * | * | -4.0 | * |

| POU domain, 2af1 | Z54283 | * | * | * | * | -2.8 | -3.0 | * | -1.7 | -2.5 | * |

| Idb3 | M60523 | * | 2.2 | 3.0 | * | * | -3.7 | * | -2.2 | -2.8 | * |

For cells stimulated with Ag and B7, the fold change was calculated by comparing signal intensities with naïve (0 hr) cell signal intensities. For cells stimulated with Ag-B7 in presence of IL-12, IFNα or TSA, the fold change was determined by comparison with cells stimulated with only Ag-B7 at each of the respective time points. IL-2 was present in all cultures. Fold changes are shown only if they were ≥ 1.70 and had a change p-value ≤0.05. An * indicates no change or no significant change based on the selection criteria. Only selected genes are shown: a complete listing of regulated genes is provided in Supplementary Tables. (Note: To avoid duplication the genes shown in figure 2 are not included in Table II).

The data obtained using oligonucleotide microarray analysis is quite robust in that it agrees well with results obtained on examination of both mRNA levels by RT-PCR and protein levels for a number of genes including grzB, IFNγ, CD25 (6, 22, 23), FasL, OX40, 4-1BB and others (our unpublished results). Some of the genes whose expression is upregulated in a signal 3-dependent manner have previously been reported to be regulated by IL-12, for example CCR5 (24), or by IFNα, for example CXCL-10 (25).

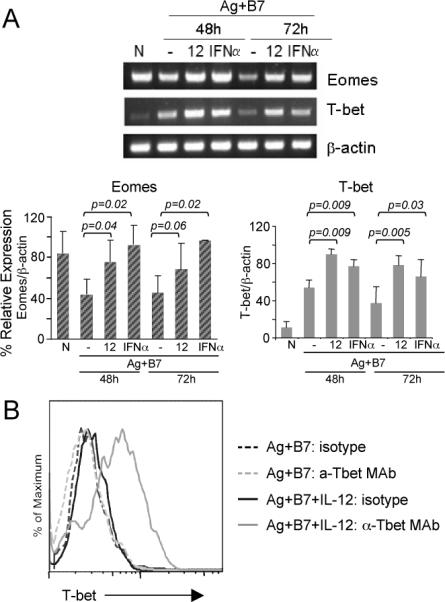

IL-12 and IFNα/β regulate expression levels of a number of transcription factors (Table 2 and Tables SII-III). Of particular interest was eomesodermin (Eomes), a T-box family transcription factor that has a role in regulating genes important for CD8 T cell functions (26). T-bet (27, 28), a highly homologous member of the same T-box family, also has an important a role in CTL differentiation but is not represented on the Affymetrix MG U74Av2 gene chip. We therefore examined the regulation of Eomes and T-bet mRNA in response to different signals using RT-PCR. T-bet mRNA expression was low in naïve cells, increased in response to Ag-B7, and was further increased and sustained when either IL-12 or IFNα were present (Fig. 3A). In contrast, and consistent with the array analysis, Eomes mRNA was expressed at a high level in naïve cells and decreased upon stimulation with Ag-B7, but was maintained at a high level when either IL-12 or IFNα were present (Fig. 3A). Expression of Eomes mRNA was somewhat higher in response to IFNα than to IL-12 (Fig. 3A), and two independent experiments using real-time PCR showed that expression was 1.7 +/- 0.1 fold higher in response to IFNα than to IL-12 (data not shown). Thus, both IL-12 and IFNα/β cause the sustained high expression of these important transcription factors to allow them to contribute to CD8 T cell differentiation. IL-12-dependent up-regulation of T-bet expression at the protein level was confirmed by intracellular staining with an anti-T-bet mAb (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. IL-12- and IFNα-dependent regulation of T-bet and eomesodermin mRNA expression.

(A) Total RNA was isolated from naïve (CD44lo) OT-I CD8 T cells (0-h) or from purified OT-I CD8 T cells stimulated with Ag-B7 in presence of the indicated cytokines for 48 and 72h, and the mRNA expression level of T-bet and Eomes was determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. The linear range of amplification of transcripts was determined as described in Materials and Methods. The graphs represent mRNA quantification done by densitometry for three independent experiments. For each condition, the relative mRNA expression is shown as the mean ± S.D. Student's t-test was performed comparing IL-12 or IFNα with Ag-B7 alone and p-values are shown. (B) Naïve OT-I T cells were stimulated for 72hr with Ag-B7 alone or along with IL-12, as indicated, and the cells stained with anti-Tbet mAb or isotype control Ab and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Our results would appear to be in partial contradiction to a recent study concluding that IL-12 represses Eomes expression during a response to LM (29). They found that Eomes was expressed in naïve cells and increased somewhat at the peak of the effector response, as we do, but that cells in IL-12-deficient mice expressed Eomes at a higher level. Largely from this, they concluded that IL-12 represses Eomes expression. Given our results, the more likely interpretation is that because IFN-α/β levels are increased in IL-12-deficient mice, IFN-α/β becomes the predominant signal 3 cytokine, while IL-12 is the predominant signal 3 cytokine in the WT mice as our studies of responses to LM have shown (13). Thus, it is likely that Eomes expression in WT mice is lower not because it is being repressed by IL-12, but because IL-12 does not induce expression to as high a level in the WT mice as does IFN-α/β in the deficient mice.

Chromatin remodeling in CD8 T cell differentiation

Remodeling of chromatin to establish open or condensed structures that promote gene activation or repression, respectively, plays a major role in differentiation of many cell types, including differentiation of CD4 T cells to become TH1 or TH2 effector cells (30). Chromatin remodeling by DNA demethylation and/or histone acetylation has been demonstrated for a few genes expressed during CD8 T cell differentiation (31, 32) and there is emerging evidence that these mechanisms may contribute to the more rapid responsiveness of memory CD8 T cells (33-36). The temporal, coordinated gene expression patterns observed in response to IL-12 and IFNα/β (Fig. 1E and Fig. 2) suggest that these global events may be mediated, in part, by chromatin remodeling. The expression of genes for grzB, IFNγ and many other proteins are upregulated in response to Ag-B7 within 24h but then decline at later times, while IL-12 or IFNα maintain and increase the expression at later times (Fig. 1B, C, E), raising the possibility that the cytokines may promote an open chromatin structure to allow continued and increased transcription.

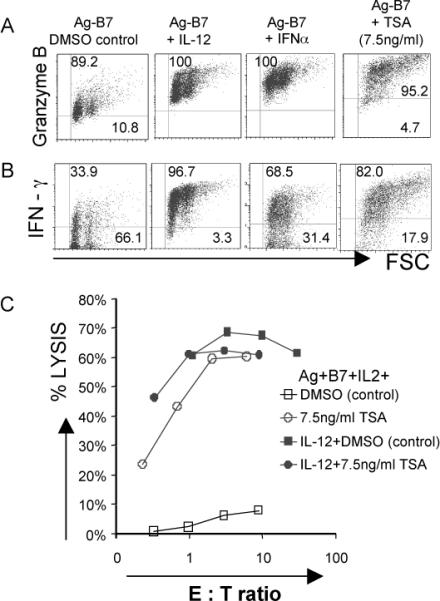

Gene accessibility and transcriptional activity can be regulated by histone acetylation levels, with increased histone acetylation generally leading to greater accessibility, and de-acetylation mediated by histone deacetylases (HDACs) leading to decreased transcriptional activity. We therefore examined the effects of pharmacological agents that alter histone acetylation levels by inhibiting HDAC activity. When naïve CD8 T cells were stimulated with Ag-B7 for 3 days, the addition of trichostatin A (TSA), an HDAC inhibitor, resulted in a large increase in grzB expression (Fig. 4A), development of the capacity to produce IFNγ (Fig. 4B) and induction of potent cytolytic activity (Fig. 4C). Essentially the same results were obtained with sodium butyrate (1mM), another HDAC inhibitor (data not shown). For both TSA and sodium butyrate, the responses required the presence of an Ag stimulus. Thus, inhibition of HDACs mimics the effects of IL-12 and IFNα/β on the development of functional activities by naïve CD8 T cells responding to Ag-B7.

Figure 4. Inhibition of histone deacetylation mimics signal 3 cytokine effects on CD8 T cell differentiation.

Purified CD44lo OT-1 CD8 T cells were stimulated for 3 days with Ag-B7 coated aAPC alone or with IL-12, IFNα or trichostatin A (TSA) (7.5ng/ml). TSA was dissolved in DMSO, and controls having Ag-B7 and DMSO were included.

(A-B) Expression of grzB and IFNγ by intracellular staining. Isotype controls were run for all samples (not shown), and gates set so that > 98% of events fell into the lower quadrant for the controls.

(C) Cytolytic activity measured by 51Cr release assay using E.G7 target cells.

The effects of HDAC inhibitors suggested that IL-12 and IFNα/β might act, in part, by promoting histone acetylation of genes expressed during differentiation, and we examined this directly for the grzB locus. The grzB proximal promoter region about 250bp upstream from the transcriptional start site (TSS) becomes DNaseI hypersensitive upon TCR ligation in the presence of a mitogenic signal (37), suggestive of chromatin remodeling, and we therefore examined the histone acetylation status of this region (Fig. 5). Quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation (qCHIP) was carried out using antibodies specific for acetylated H3 and H4 histones. Naïve CD8 T cells exhibited low basal H3 and H4 acetylation at the grzB proximal promoter region (Fig. 5A,B). After in vitro stimulation with Ag-B7 for 48h the promoter exhibited little or no increase in H3 acetylation and an increase in H4 acetylation in comparison to naïve cells. In contrast, when cells were stimulated with Ag-B7 and either IL-12, IFNα or TSA there was a substantial increase in H3 acetylation over the levels seen in cells stimulated with two signals, while relatively little further change was seen in H4 acetylation.

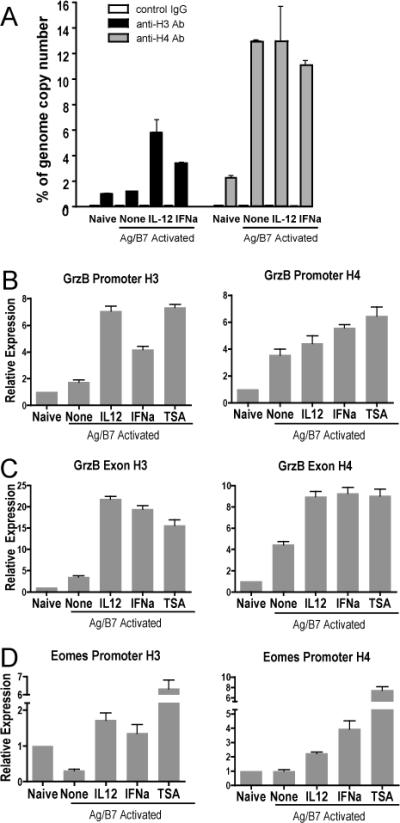

Figure 5. IL-12 and IFNα promote histone hyperacetylation at the grzB and Eomes gene loci during CD8 T cell differentiation.

Purified CD44lo OT-I CD8 T cells were used as naïve control or were stimulated with Ag-B7 aAPC alone or with IL-12, IFNα or TSA (7.5ng/ml). Cells were harvested at 48h, processed, and examined by crosslinked-CHIP and qRT-PCR for acetylated histones H3 and H4. (A) Association of H3 and H4 histones with the grzB promoter, expressed as template copy numbers as a percent of whole genome copy number. Error bars show ranges for duplicate samples. (B-D) Association of H3 and H4 histones with the grzB promoter (B), grzB distal region (B) and the Eomes promoter (C) regions. Template copy numbers for each condition were internally normalized with their respective input control. Relative expression is calculated as the ratio of template copy numbers of each sample relative to the naïve control in each experiment, and is shown as mean with SEM of 2 or 3 independent experiments with duplicate samples for each. In comparison to naïve cells, activation with Ag-B7 resulted in significant increases of acetylated H3 and H4 histones with the promoter and exon regions of GrzB (p < 0.05), a significant decrease in acetylated H3 histone association with the Eomes promoter (p < 0.001), and no change in association of acetylated H4 with the Eomes promoter (p = 0.5). In comparison to cells stimulated with just Ag-B7, association of acetylated H3 and H4 histones was significantly greater when IL-12, IFNα or TSA was added (p < 0.03), with one exception. The exception was acetylated H4 association with the GrzB promoter, where the additions did not cause a significant increase (p > 0.05).

Histone hyperacetylation is often found to extend to distal regions of genes, and we therefore also examined the region of the grzB locus spanning the end of Exon 3 and extending into Intron C. H3 and H4 acetylation was low for this region in naïve cells, and H3 acetylation increased little upon Ag-B7 stimulation, but was strongly increased when IL-12, IFNα or TSA were present (Fig. 5C). H4 acetylation increased upon stimulation with Ag-B7, and exhibited significant further increases in the presence of IL-12, IFNα or TSA. These results therefore directly demonstrate that for at least one of the genes whose expression depends upon a signal 3 cytokine, the cytokines induce histone hyperacetylation in both the promoter and distal regions that could contribute to the increased and sustained expression of the critical differentiation gene.

We also examined the associations of acetylated histones with the promoter region of Eomes. Unlike grzB, Eomes mRNA is expressed at high levels in naïve cells and declines upon stimulation with Ag-B7, but is maintained at a high level if IL-12 or IFNα are present (Fig. 3A). The promoter region of Eomes about 250bp upstream of the transcription start site was examined, as this region does not exhibit similarity with any other T-box family member (NCBI/Basic Local Alignment Search Tool). There was a significant decrease in association of acetylated H3 histone with this region upon stimulation of naïve cells with Ag-B7 alone, and a substantial increase if IL-12, IFNα or TSA was present (Fig. 5D). Levels of associated acetylated H4 histone were low in naïve cells and did not change upon stimulation with Ag-B7, but also showed a substantial increase in response to IL-12, IFNα and TSA. Thus, IL-12 and IFNα/β stimulate increased associations of acetylated histones with the Eomes promoter region that parallel the mRNA expression levels of this critical transcription factor.

To further compare the effects of TSA with those of IL-12 and IFNα/β at the level of individual gene expression we carried out oligonucleotide array analysis of cells stimulated with Ag-B7 in the presence or absence of 7.5ng/ml TSA for 72h. In comparison to Ag-B7 alone, TSA significantly altered (fold change ≥ 1.7, p ≤ 0.05) the expression levels of 1,473 genes. This included 185 of the 355 genes regulated in common by IL-12 and IFNα, and 140 of these 185 were changed in the same direction as with the cytokines, including Eomes, grzB, IFNγ, RGGTase β, CD25, CCR5, CCR2, XCl-1 and others (Table II and Table SVII). Thus, almost half of the genes whose expression is sustained by IL-12 or IFNα are regulated in a similar manner by inhibiting histone deacetylation.

DISCUSSION

TCR and CD28 signals stimulate multiple rounds of CD8 T cell division (15, 16) but in the absence of a signal from IL-12 or IFNα/β survival is compromised, effector functions and memory do not develop, and the small number of cells that do survive are tolerant (4, 11, 38). Use of aAPC provides a powerful approach for studying gene regulation by IL-12 and IFNα; the signals are well defined and all of the cells become activated in a narrow time frame, thus allowing analysis of the time course of changes in gene expression levels. In contrast, this level of definition would not be feasible for cells responding in vivo due to the redundancy of the effects of IL-12 and Type I IFNs, potential modifications of the genetic program due to other signals present in vivo, and the fact that all of the T cells will not be stimulated simultaneously, instead being recruited over time as the infection progresses. Thus, the in vitro studies described here provide a baseline definition of the signal 3-dependent differentiation program, and will form the basis for studying in vivo responses in more detail by examining expression of gene products known to be regulated as part of this program. The program includes about 355 genes regulated in common by IL-12 and IFNα (Fig. 1D, E, Table SIV). This regulation is superimposed on the regulation of over 3,000 genes by TCR and CD28 signals, many of which are involved in cell cycle regulation, DNA synthesis and repair, protein translation and metabolism (Table SI). Much of the signal 3-dependent program involves regulation of genes that encode proteins of obvious relevance to the differentiation process that leads to effector and memory cells.

Once CD8 T cells have undergone an initial burst of proliferation over about three days, expansion and survival can be further increased by additional signals. IL-2 produced by CD4 helper T cells can sustain and expand effector CD8 T cell populations (39, 40). IL-12 increases the expression of CD25 (Fig. 2), thus increasing IL-2Rα protein expression and making the effector cells more responsive to this signal (23). Receptors belonging to the tumor necrosis factor receptor super family (TNFRSF) can also increase the survival of effector cells by increasing expression of anti-apoptotic genes (41). Expression levels of genes for several of these receptors, including OX-40, 4-1BB and GITR, are upregulated IL-12 and IFNα (Fig. 2 and Table II), and this has been confirmed at the level of cell surface protein expression for OX-40 and 4-1BB (42). In contrast CD27, a member of the TNFRSF that acts earlier in the response (43), was upregulated with just two signals, and expression decreased in the presence of IL-12 or IFNα (Table II). IL-12 and IFNα/β also upregulate a number of cell intrinsic defense genes including cysteine protease inhibitors (CTLA-2α and 2β) and serine protease inhibitors (spi6, spi2e, serpin5, serpin1) (Fig. 2 and Table II). Spi6 is important for protecting effector CD8 T cells from death induced by their own lytic machinery (44). In addition, IL-12 (45) and IFNa (our unpublished results) also upregulate expression of Bcl-3, a member of the IkB family of proteins that can enhance T cell survival (46). Thus, a critical part of the signal 3-dependent differentiation program involves increased expression of numerous genes that encode for proteins important for clonal expansion and survival of the effector and memory cells that develop.

Major functions of effector CD8 T cells include production of cytokines and killing of target cells by the perforin/granzyme-dependent degranulation mechanism or the FasL pathway, and IL-12 and IFNα regulate expression of genes for several of the critical proteins of these pathways. GrzB is expressed weakly and transiently in response to two signals, and is increased to high, sustained levels by IL-12 or IFNα (Fig. 1C, Fig. 2). While IL-12 and IFNα both support development of cytolytic activity (Fig. 1A), there may be differences in functional capacities depending on which signal a cell receives, since grzC and grzF mRNAs were upregulated by IL-12 but not by IFNα (Fig. 2 and Table II). Unlike granzymes, perforin mRNA and protein are strongly upregulated by two signals alone, and only marginally increased in the presence of IL-12 or IFNα (22). The Fas-dependent killing pathway also appears to require signal 3, as FasL mRNA expression is not upregulated by two signals but is strongly upregulated by IL-12 or IFNα (Fig. 2). IFNγ mRNA and protein are also strongly upregulated by both IL-12 and IFNα (Fig. 1B, Fig. 2). In contrast, TNFα mRNA is highly expressed in naïve cells, and is initially downregulated (24 hr) but later increased (72 hr) to naïve levels in response to two signals (Table II), and expression does not significantly change in response to IL-12 or IFNα, and we have confirmed this at the protein level by intracellular staining (our unpublished results). This is consistent with the fact that naïve CD8 T cells rapidly produce TNFα upon Ag stimulation, and this capacity declines as the cells become effectors (47). Thus, unlike cytolytic activity and IFNγ production, the capacity to produce TNFα does not require differentiation of the naïve cells nor does it depend upon a third signal.

To carry out its effector functions, a CD8 activated in a draining lymph node must migrate to the site of the foreign Ag. Two signals (Ag-B7) are sufficient to increase expression of a number of genes for cell adhesion and homing receptors, including CD44, MAC-2, and ICAM-I, CCR5, and CXCR3 (Fig. 2), and to downregulate genes for secondary lymphoid homing receptors, including CD62L and CCR7. Regulation of these receptors by just two signals is consistent with the observation that CD8 T cells activated in the absence of a third signal can nevertheless migrate to peripheral sites of Ag, but fail to mediate autoimmunity (38), graft rejection (12), or elimination of infected cells (48). IL-12 and IFNα/β do regulate expression of genes for several of the other receptors and chemokines involved in controlling migration, but differing patterns of regulation were observed for IL-12 versus IFNα (Fig. 2 and Table II). IL-12 upregulated CCR2 and CCR5, chemokine receptors that promote migration to inflammatory and allergic response sites, while IFNα did not increase CCR2 expression and only weakly increased CCR5 expression. IL-12 also induced chemokines that may aid recruitment of CD4 TH cells, DCs and monocytes, including CCL9, MIP-1α,β and XCl-1, while IFNα increased expression of only XCl-1. CXCL-10, a chemokine that helps attract NK cells, B cells, neutrophils and Type I T cells, was induced by IFNα, but not by IL-12. Galectin-3, an adhesion molecule, was strongly upregulated by IL-12, while galectin-9, an eosinophil attractant, was upregulated by IFNα. Finally, integrin β7 that affects migration to mucosal regions was downregulated by both IL-12 and IFNα. Thus, the signal 3-dependent differentiation program includes alterations in expression of genes for a number of receptors and chemokines important for migration into sites of foreign Ag and recruitment of additional effector cells to the sites, but the migration phenotypes of the effector cells may differ depending upon whether the third signal was provided by IL-12 or Type I IFN.

Numerous genes encoding proteins involved in signal transduction pathways are regulated by IL-12 and/or IFNα, including both cell surface receptors (e.g. IL-18R1, IL-18Racp, IL-12Rβ1 and β2, IL-2Rα) and intracellular signaling intermediates (e.g. MyD88, Traf4, Traf6, Gadd45β and Gadd45γ). This may contribute to enhanced signaling for effector responses. IL-12 and IFNα also up- or down-regulate expression of a number of genes for transcriptional factors, including ATF-3,- 4, -5, Jun-B, CREM, STAT5β, Map2k1, Sos2, regulators of G-protein signaling, and others. Two particularly interesting transcription factors regulated by IL-12 and IFNα/β are T-bet and Eomes, both of which have are involved in CD8 T cell acquisition of effector functions upon stimulation with Ag (26, 28), in part through a role in up-regulating grzB expression. T-bet expression is weakly induced in response to just two signals, and increases in response to IL-12 or IFNα. In contrast, Eomes is expressed in naïve cells and decreases in response to Ag and B7-1, but is sustained at a high level when either IL-12 or IFNα are present (Fig. 3). Thus, it appears likely that these signal 3 cytokines are promoting differentiation in part by maintaining these critical transcription factors at high levels. Many additional transcription factors and regulators are also positively or negatively regulated by IL-12 and IFNα/β (Table II), and are likely to have important roles in the differentiation program.

Histone-dependent chromatin remodeling appears to be a major mechanism by which IL-12 and IFNα/β regulate the differentiation program. Expression of many of the IL-12/IFNα-regulated genes increases early in response to Ag and B7-1 but then declines by 72 hr (Figs. 2, S1 and S2). Expression is increased and sustained by IL-12 or IFNα, suggesting that these loci might initially be accessible to transcription factors induced by Ag and B7-1, but that alterations in chromatin structure then render them inaccessible unless a signal 3 cytokine is present. The ability of trichostatin A, a class I and II HDAC inhibitor, to substitute for IL-12 or IFNα/β (Fig. 4) indicated that the cytokines might act by increasing the level of histone acetylation at critical gene loci to allow their continued transcription. We directly demonstrated this for the grzB and Eomes genes, where IL-12 or IFNα caused increased acetylation of histones H3 and H4 at the proximal promoter regions, and at the distal exon region of grzB (Fig. 5). In a similar approach using naïve CD8 T cells stimulated with anti-TCR and anti-CD28 mAb, IL-12 was shown to cause long-range hyperacetylation in the promoter and exon regions of the IFNγ gene (31). Thus, it appears that IL-12 and IFNα/β enforce the gene regulation program, at least in part, by promoting chromatin remodeling to allow sustained expression of critical genes. Both cytokines upregulate expression of mRNA for cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21, (Cdkn1A, p21), a G1/S arrest gene, by 24h, and it continued to be expressed at 72 hr (Fig. 1D). This may contribute to chromatin remodeling by prolonging the G1/S phase, since CD4 TH cells in this phase of the cell cycle have been shown to be the most susceptible to epigenetic modifications of chromatin (49, 50).

There is increasing evidence that chromatin remodeling involving histone acetylation may play an important role in differentiation of CD8 T cells to develop memory. Memory CD8 T cells exhibit increased histone acetylation levels for many of the genes that are expressed more rapidly than in naïve cells following activation, including Eomes, perforin and grzB (33-36). The results described here, together with the evidence that a signal from IL-12 or Type I IFN is required to program for memory development (13), suggest that much of the chromatin remodeling may be initiated by these cytokines. Epigenetic memory of the remodeling is likely to account for the more rapid responses of memory cells upon re-encountering Ag, and would be consistent with the fact that memory CD8 T cells do not require a third signal in order to efficiently respond to Ag and costimulation (10, 51).

CD4 T cells can provide help to CD8 T cells through CD40-dependent stimulation of DC to produce IL-12 (12), thus making this critical third signal available to the responding CD8 T cells. In experimental models that require CD4 T cell help for CD8 memory formation, increased acetylation in the memory cells has been shown to be CD4 T cell-dependent (35, 36). CD8 T cells activated with anti-TCR and anti-CD28 mAb in splenocyte cultures in the absence of CD4 T cells remain hypoacetylated and do not develop into functional memory cells upon transfer into mice, but addition of trichostatin A to these cultures to inhibit histone deacetylation results in generation of cells that survive and become functional memory cells upon transfer (36). It would seem reasonable to speculate that CD4 T cells are providing help, at least in part, by stimulating production of IL-12 and/or IFNα/β, and that trichostatin A can bypass this requirement for memory formation as it does for induction of effector functions (Fig. 4).

Kaech et.al. (52) compared gene expression levels in naïve, effector and memory CD8 T cells responding to LCMV infection, a response that depends almost completely on Type I IFNR (7). Comparison of our results to those shows that of the 355 genes regulated by both IL-12 and IFNα, about twenty-five percent were similarly up or down regulated in memory versus naïve cells. This suggests that once these genes are up or down regulated by a signal 3 cytokine during the primary response they continue to be expressed at similar levels in the memory cells. For transcription factors upregulated by IL-12 and IFNα (Tables II and SII-IV), several were also seen to be increased in the effector cells (day 8) responding to LCMV, including Blimp-1, BhlhB2, Eomes (Tbr2), and nfil3/E4BP4, while Lef-1, Tcf-7, Pou2af1, Idb3, and others were also downregulated. Nfil3/E4BP4 and BhlhB2 genes continued to be expressed at increased levels in memory cells (day 40), while Idb3 continued to be repressed. Thus, the results of our analysis of in vitro stimulated cells agree well with those for cells responding in vivo, and the comparison suggests that many of the changes in expression level that occur in response to IL-12 and IFNα/β during primary stimulation persist in resting memory cells. When naïve cells respond to Ag and costimulation in the absence of a signal 3 cytokine, survival is compromised, effector functions do not develop, and the cells that do survive long term are tolerant. This raises the possibility that the response to Ag and B7 alone may lead to permanent silencing of critical genes to result in tolerance.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 AI34824 (M.F.M.), PO1 AI35296 (M.F.M. and D.L.M) and R01 GM54706 (D.L.M.).

Abbreviations: Ag-B7, antigen and B7-1 ligand: aAPC, artificial antigen presenting cell: grzB, granzyme B: qCHIP, quantitative chromatin immunoprecipitation: TSA, trichostatin A: VV, vaccinia virus

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heath WR, Carbone FR. Cross-presentation, dendritic cells, tolerance and immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001;19:47–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinman RM, Nussenzweig MC. Avoiding horror autotoxicus: the importance of dendritic cells in peripheral T cell tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002;99:351–358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231606698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aichele P, Unsoeld H, Koschella M, Schweier O, Kalinke U, Vucikuja S. CD8 T cells specific for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus require type I IFN receptor for clonal expansion. J. Immunol. 2006;176:4525–4529. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curtsinger JM, Lins DC, Mescher MF. Signal 3 determines tolerance versus full activation of naive CD8 T cells: dissociating proliferation and development of effector function. J. Exp. Med. 2003;197:1141–1151. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curtsinger JM, Schmidt CS, Mondino A, Lins DC, Kedl RM, Jenkins MK, Mescher MF. Inflammatory cytokines provide a third signal for activation of naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 1999;162:3256–3262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtsinger JM, Valenzuela JO, Agarwal P, Lins D, Mescher MF. Type I IFNs provide a third signal to CD8 T cells to stimulate clonal expansion and differentiation. J. Immunol. 2005;174:4465–4469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolumam GA, Thomas S, Thompson LJ, Sprent J, Murali-Krishna K. Type I interferons act directly on CD8 T cells to allow clonal expansion and memory formation in response to viral infection. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:637–650. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Q, Eppolito C, Odunsi K, Shrikant PA. IL-12-Programmed long-term CD8+ T cell responeses require STAT4. J. Immunol. 2006;177:7618–7625. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mescher MF, Curtsinger JM, Agarwal P, Casey KA, Gerner M, Hammerbeck CD, Popescu F, Xiao Z. Signals required for programming effector and memory development by CD8+ T cells. Immunol. Rev. 2006;211:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtsinger JM, Lins DC, Mescher MF. CD8+ memory T cells (CD44high, Ly-6C+) are more sensitive than naive cells to (CD44low, Ly-6C-) to TCR/CD8 signaling in response to antigen. J. Immunol. 1998;160:3236–3243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt CS, Mescher MF. Adjuvant effect of IL-12: conversion of peptide antigen administration from tolerizing to immunizing for CD8+ T cells in vivo. J. Immunol. 1999;163:2561–2567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filatenkov AA, Jacovetty EL, Fischer UB, Curtsinger JM, Mescher MF, Ingulli E. CD4 T cell-dependent conditioning of dendritic cells to produce IL-12 results in CD8-mediated graft rejection and avoidance of tolerance. J. Immunol. 2005;174:6909–6917. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao Z, Casey KA, Jameson SC, Curtsinger JM, Mescher MF. Programming for CD8 T cell memory development requires IL-12 or Type I IFN. J. Immunol. 2009 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803484. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curtsinger J, Gerner MY, Lins DC, Mescher MF. Signal 3 availability limits the CD8 T cell response to a solid tumor. J. Immunol. 2007;178:6752–6760. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Stipdonk MJ, Lemmens EE, Schoenberger SP. Naive CTLs require a single brief period of antigenic stimulation for clonal expansion and differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2:423–429. doi: 10.1038/87730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curtsinger JM, Johnson CM, Mescher MF. CD8 T cell clonal expansion and development of effector function require prolonged exposure to antigen, costimulation, and signal 3 cytokine. J. Immunol. 2003;171:5165–5171. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hugues S, Fetler L, Bonifaz L, Helft J, Amblard F, Amigorena S. Distinct T cell dynamics in lymph nodes during the induction of tolerance and immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:1235–1242. doi: 10.1038/ni1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mempel TR, Henrickson SE, von Andrian UH. T-cell priming by dendritic cells in lymph nodes occurs in three distinct phases. Nature. 2004;427:154–159. doi: 10.1038/nature02238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rolle CE, Carrio R, Malek TR. Modeling the CD8+ T effector to memory transition in adoptive T-cell antitumor therapy. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2984–2992. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, Heath WR, Howard JL, Bevan MJ, Carbone FR. T cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell. 1994;76:17–27. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nandiwada SL, Li W, Zhang R, Mueller DL. p300/Cyclic AMP-Responsive Element Binding-Binding Protein Mediates Transcriptional Coactivation by the CD28 T Cell Costimulatory Receptor. J. Immunol. 2006;177:401–413. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curtsinger JM, Lins DC, Johnson CM, Mescher MF. Signal 3 tolerant CD8 T cells degranulate in response to antigen but lack granzyme B to mediate cytolysis. J. Immunol. 2005;175:4392–4399. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valenzuela J, Schmidt C, Mescher M. The roles of IL-12 in providing a third signal for clonal expansion of naive CD8 T cells. J. Immunol. 2002;169:6842–6849. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwasaki M, Mukai T, Gao P, Park WR, Nakajima C, Tomura M, Fujiwara H, Hamaoka T. A critical role for IL-12 in CCR5 induction on T cell receptor-triggered mouse CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001;31:2411–2420. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200108)31:8<2411::aid-immu2411>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matikainen S, Pirhonen J, Miettinen M, Lehtonen A, Govenius-Vintola C, Sareneva T, Julkunen I. Influenza A and sendai viruses induce differential chemokine gene expression and transcription factor activation in human macrophages. Virology. 2000;276:138–147. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pearce EL, Mullen AC, Martins GA, Krawczyk CM, Hutchins AS, Zediak VP, Banica M, DiCioccio CB, Gross DA, Mao CA, Shen H, Cereb N, Yang SY, Lindsten T, Rossant J, Hunter CA, Reiner SL. Control of effector CD8+ T cell function by the transcription factor Eomesodermin. Science. 2003;302:1041–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1090148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szabo SJ, Sullivan BM, Stemmann C, Satoskar AR, Sleckman BP, Glimcher LH. Distinct effects of T-bet in TH1 lineage commitment and IFN-gamma production in CD4 and CD8 T cells. Science. 2002;295:338–342. doi: 10.1126/science.1065543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sullivan BM, Juedes A, Szabo SJ, von Herrath M, Glimcher LH. Antigen-driven effector CD8 T cell function regulated by T-bet. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2003;100:15818–15823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2636938100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takemoto N, Intlekofer AM, Northrup JT, Wherry EJ, Reiner SL. Cutting Edge: IL-12 inversely regulates T-bet and Eomesodermin expression during pathogen-induced CD8+ T cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 2006;177:7515–7519. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avni O, Rao A. T cell differentiation: a mechanistic view. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2000;12:654–659. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou W, Chang S, Aune TM. Long-range histone acetylation of the Ifng gene is an essential feature of T cell differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2004;101:2440–2445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306002101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu Q, Wu A, Ray D, Deng C, Attwood J, Hanash S, Pipkin M, Lichtenheld M, Richardson B. DNA methylation and chromatin structure regulate T cell perforin gene expression. J. Immunol. 2003;170:5124–5132. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Araki Y, Fann M, Wersto R, Weng N. Histone acetylation facilitates rapid and robust memory CD8 T cell responses through differential expression of effector molecules (Eomesodermin and its targets: perforin and granzyme B). J. Immunol. 2008;180:8102–8108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.8102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fann M, Godlove JM, Catalfamo M, Wood WH, Chrest FJ, Chun N, Granger L, Wersto R, Madara K, Becker K, Henkart PA, Weng NP. Histone acetylation is associated with differential gene expression in the rapid and robust memory CD8(+) T-cell response. Blood. 2006;108:3363–3370. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Northrop JK, Thomas RM, Wells AD, Shen H. Epigenetic remodeling of the IL-2 and IFN-g loci in memory CD8 T cells is influenced by CD4 T cells. J. Immunol. 2006;177:1062–1069. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Northrop JK, Wells AD, Shen H. Cutting Edge: Chromatin remodeling as a molecular basis for the enhanced functionality of memory CD8 T cells. J. Immunol. 2008;181:865–868. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Babichuk CK, Duggan BL, Bleackley RC. In vivo regulation of murine granzyme B gene transcription in activated primary T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:16485–16493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hernandez J, Aung S, Marquardt K, Sherman LA. Uncoupling of proliferative potential and gain of effector function by CD8(+) T cells responding to self-antigens. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:323–333. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shrikant P, Khoruts A, Mescher MF. CTLA-4 blockade reverses CD8+ T cell tolerance to tumor by a CD4+ T cell- and IL-2-dependent mechanism. Immunity. 1999;11:483–493. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blattman JN, Grayson JM, Wherry EJ, Kaech SM, Smith KA, Ahmed R. Therapeutic use of IL-2 to enhance antiviral T-cell responses in vivo. Nat. Med. 2003;9:540–547. doi: 10.1038/nm866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Croft M. Co-stimulatory members of the TNFR family: keys to effective T-cell immunity? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003;3:609–620. doi: 10.1038/nri1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Casey KA, Mescher MF. IL-21 promotes differentiation of naive CD8 T cells to a unique effector phenotype. J. Immunol. 2007;178:7640–7648. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watts TH. TNF/TNFR family members in costimulation of T cell responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005;23:23–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hirst CE, Buzza MS, Bird CH, Warren HS, Cameron PU, Zhang M, Ashton-Rickardt PG, Bird PI. The intracellular granzyme B inhibitor, proteinase inhibitor 9, is up-regulated during accessory cell maturation and effector cell degranulation, and its overexpression enhances CTL potency. J. Immunol. 2003;170:805–815. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valenzuela JO, Hammerbeck CD, Mescher MF. Cutting edge: Bcl-3 up-regulation by signal 3 cytokine (IL-12) prolongs survival of antigen-activated CD8 T cells. J. Immunol. 2005;174:600–604. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell TC, Hildeman D, Kedl RM, Teague TK, Schaefer BC, White J, Zhu Y, Kappler J, Marrack P. Immunological adjuvants promote activated T cell survival via induction of Bcl-3. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2:397–402. doi: 10.1038/87692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crowe SR, Miller SC, Shenyo RM, Woodland DL. Vaccination with an acidic polymerase epitope of influenza virus elicits a potent antiviral T cell response but delayed clearance of an influenza virus challenge. J. Immunol. 2005;174:696–701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Appay V, Nixon DF, Donahoe SM, Gillespie GM, Dong T, King A, Ogg GS, Spiegel HM, Conlon C, Spina CA, Havlir DV, Richman DD, Waters A, Easterbrook P, McMichael AJ, Rowland-Jones SL. HIV-specific CD8(+) T cells produce antiviral cytokines but are impaired in cytolytic function. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:63–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Syrbe U, Jennrich S, Schottelius A, Richter A, Radbruch A, Hamann A. Differential regulation of P-selectin ligand expression in naive versus memory CD4+ T cells: evidence for epigenetic regulation of involved glycosyltransferase genes. Blood. 2004;104:3243–3248. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bird JJ, Brown DR, Mullen AC, Moskowitz NH, Mahowald MA, Sider JR, Gajewski TF, Wang CR, Reiner SL. Helper T cell differentiation is controlled by the cell cycle. Immunity. 1998;9:229–237. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80605-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmidt CS, Mescher MF. Peptide antigen priming of naive, but not memory, CD8 T cells requires a third signal that can be provided by IL-12. J. Immunol. 2002;168:5521–5529. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaech SM, Hemby S, Kersh E, Ahmed R. Molecular and functional profiling of memory CD8 T cell differentiation. Cell. 2002;111:837–851. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.