Abstract

Immunogold localization revealed that OmcS, a cytochrome that is required for Fe(III) oxide reduction by Geobacter sulfurreducens, was localized along the pili. The apparent spacing between OmcS molecules suggests that OmcS facilitates electron transfer from pili to Fe(III) oxides rather than promoting electron conduction along the length of the pili.

There are multiple competing/complementary models for extracellular electron transfer in Fe(III)- and electrode-reducing microorganisms (8, 18, 20, 44). Which mechanisms prevail in different microorganisms or environmental conditions may greatly influence which microorganisms compete most successfully in sedimentary environments or on the surfaces of electrodes and can impact practical decisions on the best strategies to promote Fe(III) reduction for bioremediation applications (18, 19) or to enhance the power output of microbial fuel cells (18, 21).

The three most commonly considered mechanisms for electron transfer to extracellular electron acceptors are (i) direct contact between redox-active proteins on the outer surfaces of the cells and the electron acceptor, (ii) electron transfer via soluble electron shuttling molecules, and (iii) the conduction of electrons along pili or other filamentous structures. Evidence for the first mechanism includes the necessity for direct cell-Fe(III) oxide contact in Geobacter species (34) and the finding that intensively studied Fe(III)- and electrode-reducing microorganisms, such as Geobacter sulfurreducens and Shewanella oneidensis MR-1, display redox-active proteins on their outer cell surfaces that could have access to extracellular electron acceptors (1, 2, 12, 15, 27, 28, 31-33). Deletion of the genes for these proteins often inhibits Fe(III) reduction (1, 4, 7, 15, 17, 28, 40) and electron transfer to electrodes (5, 7, 11, 33). In some instances, these proteins have been purified and shown to have the capacity to reduce Fe(III) and other potential electron acceptors in vitro (10, 13, 29, 38, 42, 43, 48, 49).

Evidence for the second mechanism includes the ability of some microorganisms to reduce Fe(III) that they cannot directly contact, which can be associated with the accumulation of soluble substances that can promote electron shuttling (17, 22, 26, 35, 36, 47). In microbial fuel cell studies, an abundance of planktonic cells and/or the loss of current-producing capacity when the medium is replaced is consistent with the presence of an electron shuttle (3, 14, 26). Furthermore, a soluble electron shuttle is the most likely explanation for the electrochemical signatures of some microorganisms growing on an electrode surface (26, 46).

Evidence for the third mechanism is more circumstantial (19). Filaments that have conductive properties have been identified in Shewanella (7) and Geobacter (41) species. To date, conductance has been measured only across the diameter of the filaments, not along the length. The evidence that the conductive filaments were involved in extracellular electron transfer in Shewanella was the finding that deletion of the genes for the c-type cytochromes OmcA and MtrC, which are necessary for extracellular electron transfer, resulted in nonconductive filaments, suggesting that the cytochromes were associated with the filaments (7). However, subsequent studies specifically designed to localize these cytochromes revealed that, although the cytochromes were extracellular, they were attached to the cells or in the exopolymeric matrix and not aligned along the pili (24, 25, 30, 40, 43). Subsequent reviews of electron transfer to Fe(III) in Shewanella oneidensis (44, 45) appear to have dropped the nanowire concept and focused on the first and second mechanisms.

Geobacter sulfurreducens has a number of c-type cytochromes (15, 28) and multicopper proteins (12, 27) that have been demonstrated or proposed to be on the outer cell surface and are essential for extracellular electron transfer. Immunolocalization and proteolysis studies demonstrated that the cytochrome OmcB, which is essential for optimal Fe(III) reduction (15) and highly expressed during growth on electrodes (33), is embedded in the outer membrane (39), whereas the multicopper protein OmpB, which is also required for Fe(III) oxide reduction (27), is exposed on the outer cell surface (39).

OmcS is one of the most abundant cytochromes that can readily be sheared from the outer surfaces of G. sulfurreducens cells (28). It is essential for the reduction of Fe(III) oxide (28) and for electron transfer to electrodes under some conditions (11). Therefore, the localization of this important protein was further investigated.

OmcS antibodies.

Polyclonal OmcS antibodies were raised against the purified OmcS protein (38) in rabbits (New England Peptide, Gardner, MA). The third-bleed crude antiserum was incubated with membrane-blotted OmcS (100 μg) and washed with TBST buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.5 M NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20). The OmcS antibodies were eluted with 0.1 M glycine-HCl (pH 2.7) buffer and then neutralized with 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). The purified OmcS antibodies were tested for specificity using Western blot analysis (One-Step Western complete kit with tetramethyl benzidine [TMB]; GenScript) of total proteins prepared from cell lysates of the G. sulfurreducens wild type and the mutant strain (28) in which the gene encoding OmcS had been deleted. Total proteins (10 μg) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, blotted onto membranes using a semidry transfer cell (Bio-Rad), and incubated with the purified OmcS antibodies. Only one band with a molecular mass corresponding to that of the OmcS protein (i.e., 50 kDa) was detected with Western blot analysis in the wild-type cell lysate, whereas no bands were detected in the cell lysate from the OmcS deletion mutant (data not shown).

Localization of OmcS.

In order to localize OmcS, ca. 20 μl of culture was placed on a 400-mesh carbon-coated copper grid and incubated for 5 min. The grids were floated upside down in 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing purified OmcS antibodies (diluted 1:50 in PBS with 0.3% bovine serum albumin [BSA]) for an hour at room temperature, washed three times in 1× PBS, and then incubated for 1 h with anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with 10-nm-gold-labeled secondary antibody (Sigma) in PBS with 0.3% BSA. Samples were stained with 2% uranyl acetate and were observed using a JEOL 100 transmission electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV. Images were taken digitally using the MaxIm-DL software and analyzed using ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/index.html).

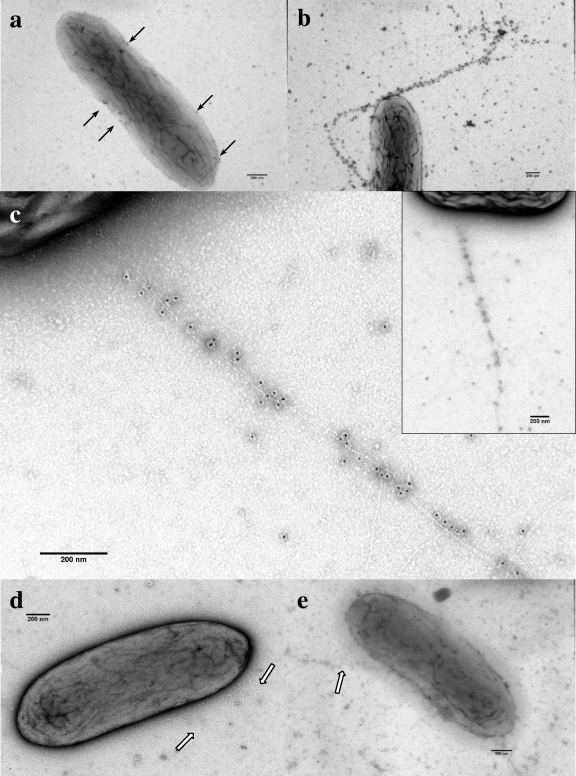

During early to mid-log growth in medium containing acetate (15 mM) as the electron donor and fumarate (20 mM) as the electron acceptor, OmcS was in low abundance and localized primarily on the outer surfaces of the cells (Fig. 1a). However, in cultures from late log or stationary phase in the same medium, the gold-labeled antibodies appeared as strands emanating from the cells (Fig. 1b and c and see Fig. SA1 in the supplemental material). At a higher magnification, it was apparent that OmcS was associated with filaments with the same diameter and morphology as those reported (41) for the conductive pili of G. sulfurreducens (Fig. 1c). Of 100 randomly sampled cells, 26 had one or more filaments with extensive OmcS coverage. When a strain of G. sulfurreducens in which the gene for OmcS had been deleted was examined in the same manner, there was no gold labeling associated with the filaments during mid-log growth (Fig. 1d) or during stationary-phase growth (Fig. 1e). By comparing the wild-type mid-log (Fig. 1a)/stationary phases (Fig. 1b and Fig. SA1) to the OmcS deletion mutant mid-log (Fig. 1d)/stationary phases (Fig. 1e), it was apparent that the labeling increased over time in the wild-type cells, whereas the labeling remained minimal for the mutant cells over time. This suggested that there was a specific association of OmcS with filaments in the wild-type strain.

FIG. 1.

Transmission electron micrographs of negatively stained G. sulfurreducens cells grown in medium with fumarate as the electron acceptor and then successively labeled with anti-OmcS rabbit polyclonal antibodies and anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with 10-nm-gold-labeled secondary antibody. (a) Mid-log-phase cell with arrows indicating the cell surface localization of gold particles associated with OmcS. (b) Late-log-phase cell with filaments labeled with gold particles. (c) A higher magnification of filaments from the late-log-phase cell is shown in the inset. (d and e) Lack of filament labeling in a mid-log-phase (d) and stationary-phase (e) cell of the OmcS deletion mutant. Arrows indicate unlabeled filaments.

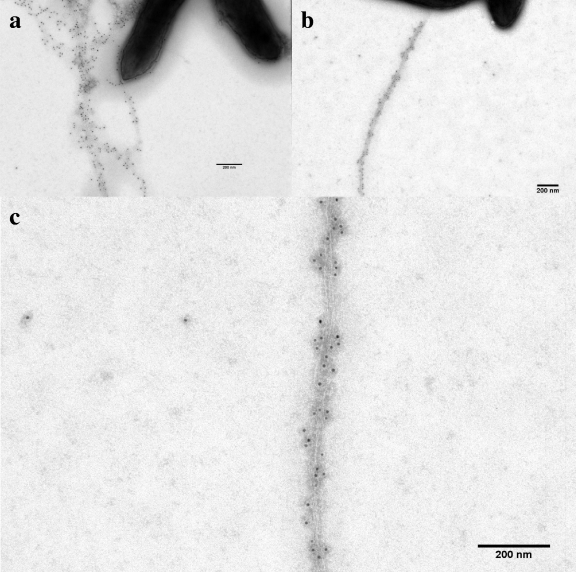

In order to localize OmcS during growth on Fe(III) oxide, cells were grown with acetate (20 mM) and poorly crystalline Fe(III) oxide (100 mmol/liter) as previously described (23). The abundant Fe(III) oxide particles occluded the antibody-labeled OmcS and filaments. Therefore, the culture was fixed anaerobically with paraformaldehyde (2% final concentration) and glutaraldehyde (0.5%) at room temperature for an hour and then treated with oxalate solution (ammonium oxalate, 28 g/liter; oxalic acid, 15 g/liter) in order to dissolve the Fe(III) oxide (23). Cells were concentrated by centrifugation (2,300 × g, 5 min) and then placed on the grids to carry out immunogold labeling with anti-OmcS antibodies as described above. OmcS was abundant and associated with filaments in these cultures (Fig. 2 and see Fig. SA2 in the supplemental material). Over half (54) of the 100 randomly selected cells had one or more OmcS-adorned filaments. Analysis of the abundance of gold particles on individual pili (see Fig. SA3 in the supplemental material) revealed that the average distance between two gold particles was 28.6 ± 10.5 nm.

FIG. 2.

Transmission electron micrographs of negatively stained G. sulfurreducens grown in medium with Fe(III) oxide as the electron acceptor, labeled with anti-OmcS rabbit polyclonal antibodies and with anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with 10-nm-gold-labeled secondary antibody. (a and b) Mid-log-phase cells; (c) higher magnification of the same OmcS-labeled filaments shown in panel b.

Implications.

The results demonstrate that the c-type cytochrome OmcS was associated with filaments which had the same diameter and morphology as the previously reported (41) conductive pili of G. sulfurreducens. The concept of cytochromes aligning with conductive filaments of Shewanella oneidensis was previously proposed but not directly demonstrated (7), and as detailed above, subsequent studies observed that the cytochromes that were proposed to be associated with Shewanella nanowires were not on filaments but were in other extracellular locations (24, 25, 30, 40, 43).

Although OmcS was associated with the pili of G. sulfurreducens, the apparent spacing between the individual OmcS molecules was much greater than the ca. 2 nm or less that is typically considered necessary for effective electron transfer between cytochromes (16, 37). It is conceivable that steric hindrances (9) or artifacts generated in the sample preparation failed to reveal an actual closer association of the cytochromes or that OmcS is interspersed along the pili with one or more of the other redox-active proteins that are on the outer surfaces of G. sulfurreducens cells (27, 28, 33). If so, then OmcS, or a combination of OmcS and other redox-active proteins, could aid in electron transfer along the length of the pili. However, with the data presently available, a more likely explanation is that OmcS facilitates electron transfer from the pili to Fe(III) oxides. OmcS effectively reduces Fe(III) oxide in vitro, and the multiple hemes and low redox potential of OmcS (38) may be ideally suited to overcome kinetic barriers to direct electron transfer from the pili to Fe(III) oxides. In this model, electrons are conducted along the pili as the result of the intrinsic conductive properties of the pili, but OmcS is required for electron transfer from the pili to Fe(III) oxides.

In addition to serving as mediators of electron transfer, abundant, multiheme cytochromes, such as OmcS, may function as capacitors, accepting and temporarily storing electrons, when cells are transitioning between Fe(III) oxide sources (6). The display of capacitor cytochromes on filaments would facilitate the rapid discharge of electrons when contact is established with fresh Fe(III) oxide sources or other extracellular electron acceptors.

These studies emphasize that the distribution of outer surface proteins and their interactions are poorly understood in Geobacter species. Further investigations are warranted if the full potential of these organisms in practical applications, such as bioremediation and conversion of organic compounds to electricity, are to be realized.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Office of Science (BER), U.S. Department of Energy, cooperative agreement no. DE-FC02-02ER63446, and Office of Naval Research grant N00014-10-1-0084.

We thank Dale Callaham for his guidance in transmission electron microscopy techniques and helpful discussions. We are grateful for the excellent technical support of Joy Ward and Manju Sharma.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 April 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beliaev, A., D. Saffarini, J. McLaughlin, and D. Hunnicutt. 2001. MtrC, an outer membrane decahaem c cytochrome required for metal reduction in Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. Mol. Microbiol. 39:722-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beliaev, A. S., and D. A. Saffarini. 1998. Shewanella putrefaciens mtrB encodes an outer membrane protein required for Fe(III) and Mn(IV) reduction. J. Bacteriol. 180:6292-6297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bond, D. R., and D. R. Lovley. 2005. Evidence for involvement of an electron shuttle in electricity generation by Geothrix fermentans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2186-2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borloo, J., B. Vergauwen, L. De Smet, A. Brige, B. Motte, B. Devreese, and J. Van Beeumen. 2007. A kinetic approach to the dependence of dissimilatory metal reduction by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 on the outer membrane cytochromes c OmcA and OmcB. FEBS J. 274:3728-3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bretschger, O., A. Obraztsova, C. A. Sturm, I. S. Chang, Y. A. Gorby, S. B. Reed, D. E. Culley, C. L. Reardon, S. Barua, M. F. Romine, J. Zhou, A. S. Beliaev, R. Bouhenni, D. Saffarini, F. Mansfeld, B.-H. Kim, J. K. Fredrickson, and K. H. Nealson. 2007. Current production and metal oxide reduction by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 wild type and mutants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:7003-7012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esteve-Nunez, A., J. Sosnik, P. Visconti, and D. R. Lovley. 2008. Fluorescent properties of c-type cytochromes reveal their potential role as an extracytoplasmic electron sink in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Environ. Microbiol. 10:497-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorby, Y. A., S. Yanina, J. S. McLean, K. M. Rosso, D. Moyles, A. Dohnalkova, T. J. Beveridge, I. S. Chang, B. H. Kim, K. S. Kim, D. E. Culley, S. B. Reed, M. F. Romine, D. A. Saffarini, E. A. Hill, L. Shi, D. A. Elias, D. W. Kennedy, G. Pinchuk, K. Watanabe, S. Ishii, B. Logan, K. H. Nealson, and J. K. Fredrickson. 2006. Electrically conductive bacterial nanowires produced by Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1 and other microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:11358-11363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gralnick, J. A., and D. K. Newman. 2007. Extracellular respiration. Mol. Microbiol. 65:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffiths, G. 1993. Fine structure immunocytochemistry. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 10.Hartshorne, R. S., B. N. Jepson, T. A. Clarke, S. J. Field, J. Fredrickson, J. Zachara, L. Shi, J. N. Butt, and D. J. Richardson. 2007. Characterization of Shewanella oneidensis MtrC: a cell-surface decaheme cytochrome involved in respiratory electron transport to extracellular electron acceptors. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 12:1083-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holmes, D. E., S. K. Chaudhuri, K. P. Nevin, T. Mehta, B. A. Methe, A. Liu, J. E. Ward, T. L. Woodard, J. Webster, and D. R. Lovley. 2006. Microarray and genetic analysis of electron transfer to electrodes in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Environ. Microbiol. 8:1805-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes, D. E., T. Mester, R. A. O'Neil, L. A. Perpetua, M. J. Larrahondo, R. Glaven, M. L. Sharma, J. E. Ward, K. P. Nevin, and D. R. Lovley. 2008. Genes for two multicopper proteins required for Fe(III) oxide reduction in Geobacter sulfurreducens have different expression patterns both in the subsurface and on energy-harvesting electrodes. Microbiology 154:1422-1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue, K., X. Qian, L. Morgado, B. C. Kim, T. Mester, M. Izallalen, C. A. Salgueiro, and D. R. Lovley. 2010. Purification and characterization of OmcZ, an outer surface, octaheme c-type cytochrome essential for optimal current production by Geobacter sulfurreducens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:3999-4007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lanthier, M., K. B. Gregory, and D. R. Lovley. 2008. Growth with high planktonic biomass in Shewanella oneidensis fuel cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 278:29-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leang, C., M. V. Coppi, and D. R. Lovley. 2003. OmcB, a c-type polyheme cytochrome, involved in Fe(III) reduction in Geobacter sulfurreducens. J. Bacteriol. 185:2096-2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leys, D., and N. S. Scrutton. 2004. Electrical circuitry in biology: emerging principles from protein structure. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14:642-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lies, D. P., M. E. Hernandez, A. Kappler, R. E. Mielke, J. A. Gralnick, and D. K. Newman. 2005. Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 uses overlapping pathways for iron reduction at a distance and by direct contact under conditions relevant for biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:4414-4426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lovley, D. R. 2006. Bug juice: harvesting electricity with microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:497-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lovley, D. R. 2008. Extracellular electron transfer: wires, capacitors, iron lungs, and more. Geobiology 6:225-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lovley, D. R. 2008. The microbe electric: conversion of organic matter to electricity. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 19:564-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lovley, D. R. 2006. Microbial fuel cells: novel microbial physiologies and engineering approaches. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 17:327-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lovley, D. R., J. D. Coates, E. L. Blunt-Harris, E. J. P. Phillips, and J. C. Woodward. 1996. Humic substances as electron acceptors for microbial respiration. Nature 382:445-448. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovley, D. R., and E. J. P. Phillips. 1988. Novel mode of microbial energy metabolism: organic carbon oxidation coupled to dissimilatory reduction of iron or manganese. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:1472-1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lower, B. H., R. Yongsunthon, L. Shi, L. Wildling, H. J. Gruber, N. S. Wigginton, C. L. Reardon, G. E. Pinchuk, T. C. Droubay, J. F. Boily, and S. K. Lower. 2009. Antibody recognition force microscopy shows that outer membrane cytochromes OmcA and MtrC are expressed on the exterior surface of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:2931-2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall, M. J., A. S. Beliaev, A. C. Dohnalkova, D. W. Kennedy, L. Shi, Z. Wang, M. I. Boyanov, B. Lai, K. M. Kemner, J. S. McLean, S. B. Reed, D. E. Culley, V. L. Bailey, C. J. Simonson, D. A. Saffarini, M. F. Romine, J. M. Zachara, and J. K. Fredrickson. 2006. c-Type cytochrome-dependent formation of U(IV) nanoparticles by Shewanella oneidensis. PLoS Biol. 4:e268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marsili, E., D. B. Baron, I. D. Shikhare, D. Coursolle, J. A. Gralnick, and D. R. Bond. 2008. Shewanella secretes flavins that mediate extracellular electron transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:3968-3973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehta, T., S. E. Childers, R. Glaven, D. R. Lovley, and T. Mester. 2006. A putative multicopper protein secreted by an atypical type II secretion system involved in the reduction of insoluble electron acceptors in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Microbiology 152:2257-2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehta, T., M. V. Coppi, S. E. Childers, and D. R. Lovley. 2005. Outer membrane c-type cytochromes required for Fe(III) and Mn(IV) oxide reduction in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8634-8641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meitl, L. A., C. M. Eggleston, P. J. S. Colberg, N. Khare, C. L. Reardon, and L. Shi. 2009. Electrochemical interaction of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 and its outer membrane cytochromes OmcA and MtrC with hematite electrodes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 17:5292-5307. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myers, C. R., and J. M. Myers. 2003. Cell surface exposure of the outer membrane cytochromes of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 37:254-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myers, J. M., and C. R. Myers. 1998. Isolation and sequence of omcA, a gene encoding a decaheme outer membrane cytochrome c of Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1, and detection of omcA homologs in other strains of S. putrefaciens. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1373:237-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myers, J. M., and C. R. Myers. 2001. Role for outer membrane cytochromes OmcA and OmcB of Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1 in reduction of manganese dioxide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:260-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nevin, K. P., B. C. Kim, R. H. Glaven, J. P. Johnson, T. L. Woodard, B. A. Methe, R. J. Didonato, S. F. Covalla, A. E. Franks, A. Liu, and D. R. Lovley. 2009. Anode biofilm transcriptomics reveals outer surface components essential for high density current production in Geobacter sulfurreducens fuel cells. PLoS One 4:e5628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nevin, K. P., and D. R. Lovley. 2000. Lack of production of electron-shuttling compounds or solubilization of Fe(III) during reduction of insoluble Fe(III) oxide by Geobacter metallireducens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2248-2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nevin, K. P., and D. R. Lovley. 2002. Mechanisms for Fe(III) oxide reduction in sedimentary environments. Geomicrobiol. J. 19:141-159. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Newman, D. K., and R. Kolter. 2000. A role for excreted quinones in extracellular electron transfer. Nature 405:94-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Page, C. C., C. C. Moser, and P. L. Dutton. 2003. Mechanism for electron transfer within and between proteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 7:551-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qian, X. 2009. Investigation of Fe(III) reduction in Geobacter sulfurreducens characterization of outer surface associated electron transfer components. Ph.D. thesis. University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA.

- 39.Qian, X., G. Reguera, T. Mester, and D. R. Lovley. 2007. Evidence that OmcB and OmpB of Geobacter sulfurreducens are outer membrane surface proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 277:21-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reardon, C. L., A. C. Dohnalkova, P. Nachimuthu, D. W. Kennedy, D. A. Saffarini, B. W. Arey, L. Shi, Z. Wang, D. Moore, J. S. McLean, D. Moyles, M. J. Marshall, J. M. Zachara, J. K. Fredrickson, and A. S. Beliaev. 2010. Role of outer-membrane cytochromes MtrC and OmcA in the biomineralization of ferrihydrite by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Geobiology 8:56-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reguera, G., K. D. McCarthy, T. Mehta, J. S. Nicoll, M. T. Tuominen, and D. R. Lovley. 2005. Extracellular electron transfer via microbial nanowires. Nature 435:1098-1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ross, D. E., S. L. Brantley, and M. Tien. 2009. Kinetic characterization of OmcA and MtrC, terminal reductases involved in respiratory electron transfer for dissimilatory iron reduction in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:5218-5226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi, L., B. Chen, Z. Wang, D. A. Elias, M. U. Mayer, Y. A. Gorby, S. Ni, B. H. Lower, D. W. Kennedy, D. S. Wunschel, H. M. Mottaz, M. J. Marshall, E. A. Hill, A. S. Beliaev, J. M. Zachara, J. K. Fredrickson, and T. C. Squier. 2006. Isolation of a high-affinity functional protein complex between OmcA and MtrC: two outer membrane decaheme c-type cytochromes of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. J. Bacteriol. 188:4705-4714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi, L., D. J. Richardson, Z. Wang, S. N. Kerisit, K. M. Rosso, J. M. Zachara, and J. K. Fredrickson. 2009. The roles of outer membrane cytochromes of Shewanella and Geobacter in extracellular electron transfer. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 1:220-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi, L., T. C. Squier, J. M. Zachara, and J. K. Fredrickson. 2007. Respiration of metal (hydr)oxides by Shewanella and Geobacter: a key role for multihaem c-type cytochromes. Mol. Microbiol. 65:12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Velasquez-Orta, S. B., I. M. Head, T. P. Curtis, K. Scott, J. R. Lloyd, and H. von Canstein. 2010. The effect of flavin electron shuttles in microbial fuel cells current production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85:1373-1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Canstein, H., J. Ogawa, S. Shimizu, and J. R. Lloyd. 2008. Secretion of flavins by Shewanella species and their role in extracellular electron transfer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:615-623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang, Z., C. Liu, X. Wang, M. J. Marshall, J. M. Zachara, K. M. Rosso, M. Dupuis, J. K. Fredrickson, S. Heald, and L. Shi. 2008. Kinetics of reduction of Fe(III) complexes by outer membrane cytochromes MtrC and OmcA of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:6746-6755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiong, Y., L. Shi, B. Chen, M. U. Mayer, B. H. Lower, Y. Londer, S. Bose, M. F. Hochella, J. K. Fredrickson, and T. C. Squier. 2006. High-affinity binding and direct electron transfer to solid metals by the Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 outer membrane c-type cytochrome OmcA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128:13978-13979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.