Abstract

Nanoparticles are an attractive vaccine carrier with potent adjuvant activity. Data from our previous studies showed that immunization of mice with lecithin/glyceryl monostearate-based nanoparticles with protein antigens conjugated onto their surface induced a strong, quick, and long-lasting antigen-specific immune response. In the present study, we evaluated the feasibility of preserving the immunogenicity of protein antigens carried by nanoparticles without refrigeration using these antigen-conjugated nanoparticles as a model. The nanoparticles were lyophilized, and the immunogenicity of the antigens was evaluated in a mouse model using bovine serum albumin or the Bacillus anthracis protective antigen protein as model antigens. With proper excipients, the nanoparticles can be lyophilized while maintaining the immunogenicity of the antigens. Moreover, the immunogenicity of the model antigen conjugated onto the nanoparticles was undamaged after a relatively extended period of storage at room temperature or under accelerated conditions (37°C) when the nanoparticles were lyophilized with 5% mannitol plus 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone. To our knowledge, the present study represents an early attempt to preserve the immunogenicity of the protein antigens carried by nanoparticles without refrigeration.

Keywords: Vaccine storage, lyophilization, antibody response

1. Introduction

Cold chain refrigeration is required for the storage and distribution of most vaccines. One major challenge in vaccine development is to develop formulations that do not require refrigeration. Proteins are increasingly used as antigens to prepare vaccines. However, proteins alone are generally only weakly immunogenic, and a vaccine adjuvant is needed to improve the immunogenicity of the protein antigens (Clark and Cassidy-Hanley, 2005; Perrie et al., 2008). A growing body of evidence demonstrated the feasibility and advantages of using nanoparticles as an adjuvant or delivery system for protein antigens (Singh et al., 2007). It will be beneficial if future nanoparticle-based vaccines can be stored without refrigeration, preferably at ambient temperature, while preserving the immunogenicity of the antigens. However, it is well known that protein pharmaceuticals in liquid formulations are rarely stable enough for long-term storage. Usually, a dried solid state formulation of proteins is prepared using methods such as lyophilization to avoid or to slow down the degradation of the proteins, making it possible to store the protein pharmaceuticals for months or even years at ambient temperature (Carpenter et al., 1997). To assure the long-term stability of proteins in a dried solid state, the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the protein formulations must be higher than the planned storage temperature so that molecular motion and any associated degradation will be minimized (Carpenter et al., 1997; Chang et al., 1996; Roy et al., 1992).

Previously, we reported the preparation of nanoparticles from lecithin/glyceryl monostearate-in-water emulsions (Cui et al., 2006; Sloat et al., 2010; Yanasarn et al., 2009), which have the potential to serve as a universal protein-based antigen carrier capable of inducing strong immune responses (Sloat et al., 2010). Using two model antigens, bovine serum albumin (BSA) and the B. anthracis protective antigen (PA) protein, we showed that mice immunized with the BSA-conjugated nanoparticles (~200 nm in diameter) developed strong anti-BSA antibody responses comparable to that induced by BSA adjuvanted with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant, and stronger than that induced by BSA adsorbed onto aluminum hydroxide as an adjuvant (Sloat et al., 2010). Mice immunized with the PA-conjugated nanoparticles elicited a quick, strong, and durable anti-PA antibody response that afforded protection of the mice against a lethal dose of anthrax lethal toxin challenge (Sloat et al., 2010). We attributed the potent adjuvant activity of the nanoparticles to their ability to move the antigens into local draining lymph nodes, to enhance the uptake of the antigens by antigen-presenting cells, and to activate the antigen-presenting cells (Sloat et al., 2010).

In a preliminary study, we found that the immunogenicity of a protein antigen (BSA) conjugated onto the surface of the nanoparticles decreased significantly after only one month of storage at room temperature in an aqueous suspension. Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to use these antigen-conjugated nanoparticles as a model to evaluate the feasibility of developing a nanoparticle-based vaccine formulation that can be stored at a temperature above refrigeration temperature while maintaining the immunogenicity of the antigens. There have been extensive researches on developing new technologies that allow the storage and distribution of vaccines while avoiding cold chain. So far, the most effective approach remains to be the formulation of the vaccines into a dried solid form (Amorij et al., 2008; Chen and Kristensen, 2009). There are many methods of drying, such as freeze drying, spray drying, spray-freeze drying, vaccum drying, and supercritical fluid drying (Amorij et al., 2008). Because the freezing and/or drying processes can significantly damage the protein antigens in a vaccine formulation, excipients, often sugars, are used as a stabilizer during the freezing and/or drying steps. It is expensive to use freeze drying to generate a dried solid, but the damage to proteins during the freeze drying is minimal, and there are plenty of industrial experience (Amorij et al., 2008). Mechanistically, it is believed that the stabilizers allow the formation of a matrix of the vaccine embedded in an amorphous sugar glass. The sugar glass provides a physical barrier between particles and molecules and reduce the diffusion and mobility of molecules, and thus, prevent the aggregation and degradation of the proteins (Amorij et al., 2008). Moreover, during the drying process, the sugar replaces the water molecules in the hydrogen-bonding interaction with the protein molecules and thus help preserve the integrity of the proteins (Amorij et al., 2008).

Data from the present study showed that storage in a lyophilized form may represent a viable approach to preserve the immunogenicity of the antigens carried by nanoparticles while avoiding refrigeration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of nanoparticles

Nanoparticles were prepared as previously described (Sloat et al., 2010). Briefly, soy lecithin (3.5 mg, Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA) and glyceryl monostearate (GMS, 0.5 mg, Gattefosse Corp., Paramus, NJ) were weighed into a 7-ml glass scintillation vial. One ml of de-ionized and filtered (0.2 µm) water was added into the vial, followed by heating on a hot plate to 70–75°C with stirring and brief intermittent periods of sonication (Ultrasonic Cleaner Model 150T, VWR International, West Chester, PA). Upon formation of homogenous milky slurry, Tween 20 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added in a step-wise manner to a final concentration of 1% (v/v). The resultant emulsions were allowed to stay at room temperature while stirring to form nanoparticles. The size of the nanoparticles was determined to be 178 ± 20 nm using a Coulter N4 Plus Submicron Particle Sizer (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA). To prepare the maleimide containing nanoparticles (m-NPs), 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[4-(pmaleimideophyl) butyramide] (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL), which has a reactive maleimide group, was included in the lipid mixture (5%, w/w).

2.2. Conjugation of protein antigens onto the nanoparticles

The conjugation of the protein antigens onto the nanoparticles was completed as previously described (Cui et al., 2005; Sloat et al., 2010). We used two antigens, BSA (69 KDa, isoelectric point (pI) = 4.7) from Sigma-Aldrich and the protective antigen (PA) protein (83 KDa, pI = 5.6) from Biodefense and Emerging Infections (BEI) Research Resources Repository (Manassas, VA). Prior to the conjugation, the proteins were thiolated using 2-iminothiolane (Traut’s Reagent, Sigma-Aldrich). The proteins were diluted into phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 0.1 M with 3.0 mM EDTA, pH 8.0), followed by the addition of Traut’s reagent (20 × molar excess) and a 60 min incubation at room temperature. Thiolated proteins were purified/desalted using a PD10 column (Amersham Biosciences, Bellefonte, PA). To react the thiolated proteins with the m-NPs, 1 ml of freshly prepared m-NPs were mixed with the thiolated proteins (1 mg BSA or 0.25 mg PA) in PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4) and stirred under N2 gas for 12–14 h at room temperature. Un-conjugated proteins were removed by ultracentrifugation (1.0 × 105 g). The amount of proteins conjugated onto the nanoparticles was estimated as previously described using fluorescein-labeled proteins (Sloat et al., 2010). The size of the BSA-conjugated nanoparticles was 201 ± 5 nm, and that of the PA-conjugated nanoparticles was 197 ± 6 nm. It was estimated that about 65–70 µg of the antigen proteins (BSA or PA) were conjugated onto 1 mL of the nanoparticles (~14.2 mg by weight).

2.3. Lyophilization and storage of the nanoparticles

Thirty percent (w/v) stock solutions of potential lyoprotectants (sucrose, dextrose, mannose, PVP (average molecular weight, 40,000), mannitol, lactose, and trehalose, all from Sigma-Aldrich) were prepared with de-ionized and filtered (0.2 µm) water. To the nanoparticles in suspension, an equal volume of twice the desired concentration of the lyoprotectant was added. Upon complete mixing, the nanoparticles were frozen in liquid nitrogen overnight followed by lyophilization at −40°C for about 24 h using a FreeZone 6 Liter Freeze Dry System (Labconco, Kansas City, MO). Water was added to reconstitute the nanoparticles to a volume equal to that prior to lyophilization. The number of inversions required for the complete re-suspension of the nanoparticles was recorded.

In the storage study, BSA-conjugated nanoparticles were lyophilized with 5% mannitol and 1% of PVP and sealed into 2 ml amber vials with standard rubber stoppers and aluminum caps (Wheaton Science Products, Millvile, NJ). The vials were then stored in dark at −80°C, 4°C, room temperature (22–23°C), or 37°C for 2.5 months. The size of the nanoparticles did not change significantly after the storage. For example, after 2.5 months at 37°C, the size of the particles immediately after reconstitution was 208 ± 11 nm, compared to its original size of 201 ± 5 nm. The moisture content in the lyophilized cake after the 2.5 months of storage was determined using a gravimetric method (Shackell, 1909). The weight of the dried samples (n = 3) before and after the storage was measured and compared. Furthermore, each sample was heated at an elevated temperature (> 100°C) for 2 h, and the final weight was used to determine the moisture accumulation during the storage period. The weight gain (likely from water) was 0.18 ± 0.04%, 0.45 ± 0.11%, 0.47 ± 0.14%, and 0.30 ± 0.11% for the −80°C, 4°C, room temperature, and 37°C samples, respectively. The PA-conjugated nanoparticles were lyophilized using the optimal excipients found in the lyophilization of the BSA-nanoparticles.

2.4. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

DSC measurements were carried out using a TA Instruments Differential Scanning Calorimeter (New Castle, DE) to estimate the glass transition temperature of the samples. Samples weighing between 7 and 10 mg were sealed into the aluminum DSC pans, which were placed in sample cells under nitrogen. Samples were scanned from −20 to 200°C at 10°C per min. Mannitol, PVP, and the physical blend of mannitol and PVP were scanned once and allowed to cool before final measurements were taken. The Tg of the pure PVP was found to be about 168°C.

2.5. Immunization Studies

All mouse studies were carried out following NIH guidelines for animal use and care. BALB/c mice (female, 6–8 weeks) were from Simonsen Laboratories, Inc. (Gilroy, CA). The vaccine formulations were administered by subcutaneous injection. Except where mentioned, group of mice (n = 5) were dosed with 5 µg of antigens on days 0, 14, and 28, and euthanized and bled on day 42. As controls, mice were either left untreated or vaccinated with 5 µg of antigens adsorbed onto 50 µg aluminum hydroxide gel (Alum) (Spectrum Chemicals and Laboratory Product, New Brunswick, NJ). In an initial mouse study, BSA-nanoparticles were stored at room temperature as an aqueous suspension before being injected into mice, where all three doses were prepared one month before the first injection. Mice in the control group were left untreated or injected with freshly prepared BSA-nanoparticles. To understand whether the lyophilization per se had altered the immunogenicity of the antigens on the nanoparticles, BSA-nanoparticles or PA-nanoparticles were lyophilized, immediately reconstituted with water to its original volume prior to the lyophilization, and injected into mice within 30 min. To evaluate the immunogenicity of BSA-nanoparticles after 2.5 months of storage, BSA-nanoparticles were lyophilized, stored at the desired temperature for 2.5 months, and reconstituted within 30 min prior to injection into mice. In other words, the BSA-nanoparticles used for every dosing were stored for 2.5 months.

2.6. Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and toxin neutralization assay

The levels of anti-BSA and anti-PA IgG in serum samples were determined using ELISA (Sloat et al., 2010). EIA/RIA flat bottom, medium binding, polystyrene, 96-well plates (Corning Costar, Corning, NY) were coated with 100 ng of PA in 100 µl of carbonate buffer (0.1 M, pH 9.6) or BSA in PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4) overnight at 4°C. For anti-BSA Ab measurement, plates were washed with PBS/Tween 20 (10 mM, pH 7.4, 0.05% Tween 20) and blocked with 5% (v/v) horse serum in PBS/Tween 20 for 1 h at 37°C. Samples were diluted two-fold serially in 5% horse serum/PBS/Tween 20, added to the plates following the removal of the blocking solution, and incubated for an additional 3 h at 37°C. The serum samples were removed, and the plates were washed five times with PBS/Tween 20. Horse radish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (IgG, 5,000-fold dilution in 1.25% horse serum/PBS/Tween 20, Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) was added into the plates, followed by another hour of incubation at 37°C. Plates were again washed five times with PBS/Tween 20. The presence of bound antibody was detected following a 30 min incubation at room temperature in the presence of 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine solution (TMB, Sigma–Aldrich), followed by the addition of 0.2 M sulfuric acid (Sigma-Aldrich) as the stop solution. The absorbance was read at 450 nm. Anti-PA IgG was determined similarly; except that the 5% horse serum in PBS/Tween 20 was replaced by 4% (w/v) BSA in PBS/Tween 20 in the plate blocking and the sample dilution steps. In addition, the secondary antibody was diluted in 1% (w/v) BSA in PBS/Tween 20. The antibody titers were determined by considering an OD value higher than the mean plus two times of the standard deviation (mean + 2 × S.D.) of the negative control group as positive. Antibody titers were reported as the anti-log2 values.

The lethal toxin neutralization assay was also completed as previously described (Sloat and Cui, 2006). In brief, confluent J774A.1 cells were plated (5.0 × 104 cells/well) in sterile, 96-well, clean-bottom plates (Corning Costar) and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24 h. A fresh solution (50 µL) containing PA (400 ng/mL) and lethal factor (100 ng/mL, BEI Resources) was mixed with 50 µL of diluted serum samples and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The cell culture medium was removed, and 100 µL of the serum/lethal toxin mixture was added into each well and incubated for 3 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cell viability was determined using an MTT (3-(4, 5-Dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2, 5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide) kit (Sigma–Aldrich) with untreated and lethal toxin alone treated cells as controls.

2.7. Statistics

Statistical analyses were completed using ANOVA followed by the Fischer’s protected least significant difference procedure. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 (two tail) was considered significant.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Significant loss of immunogenicity when the antigen-conjugated nanoparticles were stored as an aqueous suspension

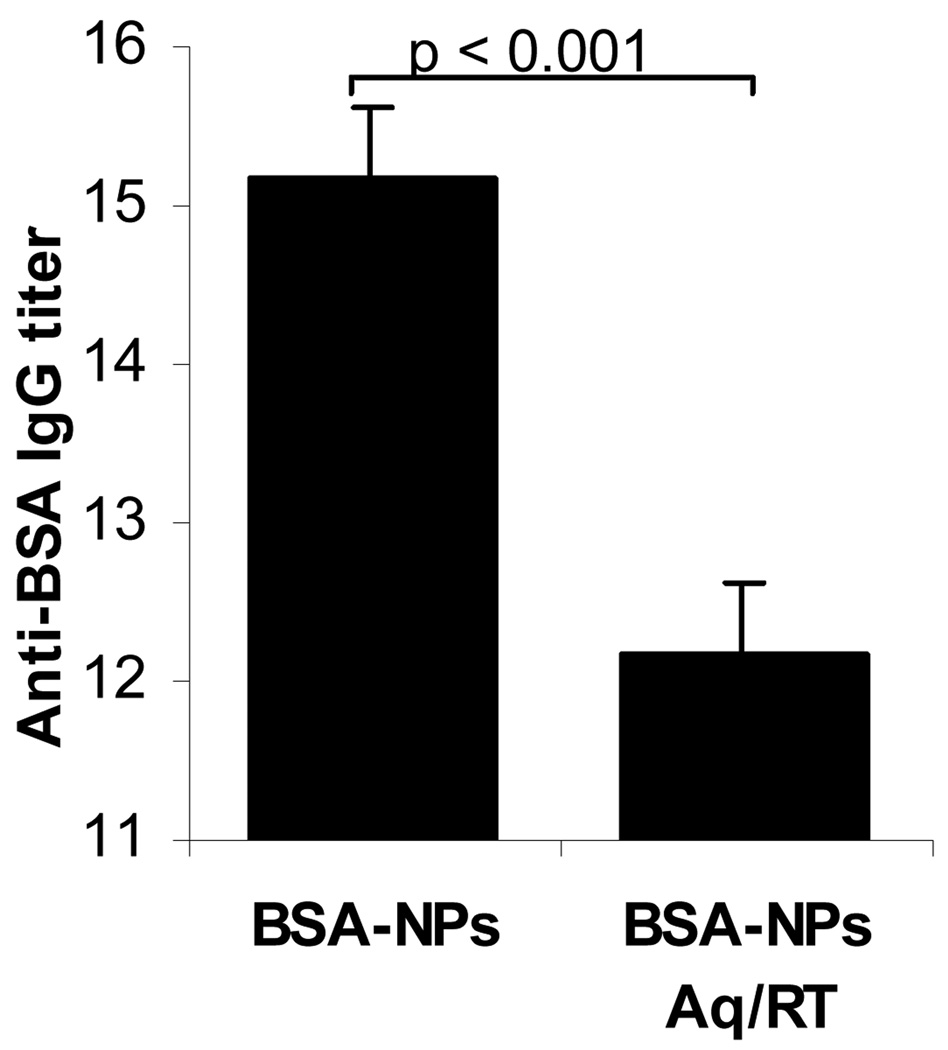

In the present study, we aimed at using the protein antigen-conjugated nanoparticles previously developed in our laboratory as a model to evaluate the feasibility of storing protein antigens carried by nanoparticles at a temperature above refrigeration temperature while maintaining the immunogenicity of the antigens. It was expected that the immunogenicity of the protein antigens conjugated onto the nanoparticles would be damaged significantly when they were stored as an aqueous suspension. To confirm it, the BSA-conjugated nanoparticles suspended in PBS were left at room temperature for up to a month and used to immunize mice. As shown in Fig. 1, the anti-BSA IgG titer induced by the BSA-nanoparticles after the storage was significantly lower than that induced by the freshly prepared BSA-nanoparticles (p < 0.001), demonstrating a significant loss of immunogenicity. Data from a preliminary study showed that the size of the BSA-nanoparticles increased from 201 ± 5 nm to 255 ± 8 nm when stored as an aqueous suspension at room temperature for only 7 days. Therefore, it was likely that particle aggregation had contributed to the loss of the immunogenicity. However, it is unclear to what extent the loss of immunogenicity was caused by the chemical degradation of the BSA proteins during the storage. In the following studies, we used this nanoparticle system as a model to test the feasibility to lyophilize the antigen-conjugated nanoparticles and to preserve the immunogenicity of the protein antigens carried by nanoparticles by storing the nanoparticles in a freeze-dried formulation.

Figure 1. Significant decrease of immunogenicity when the BSA-conjugated nanoparticles were stored as an aqueous suspension.

BSA-conjugated nanoparticles (BSA-NPs) were stored at room temperature in an aqueous suspension (BSA-NPs, Aq/RT) for upto a month, and the anti-BSA IgG titer induced by them was compared to that of freshly prepared BSA-NPs. Data shown are mean ± S.D. from group of 5 mice (anti-log2 values).

3.2. Lyophilization of the antigen-conjugated nanoparticles: particle size, cake formation, and reconstitution

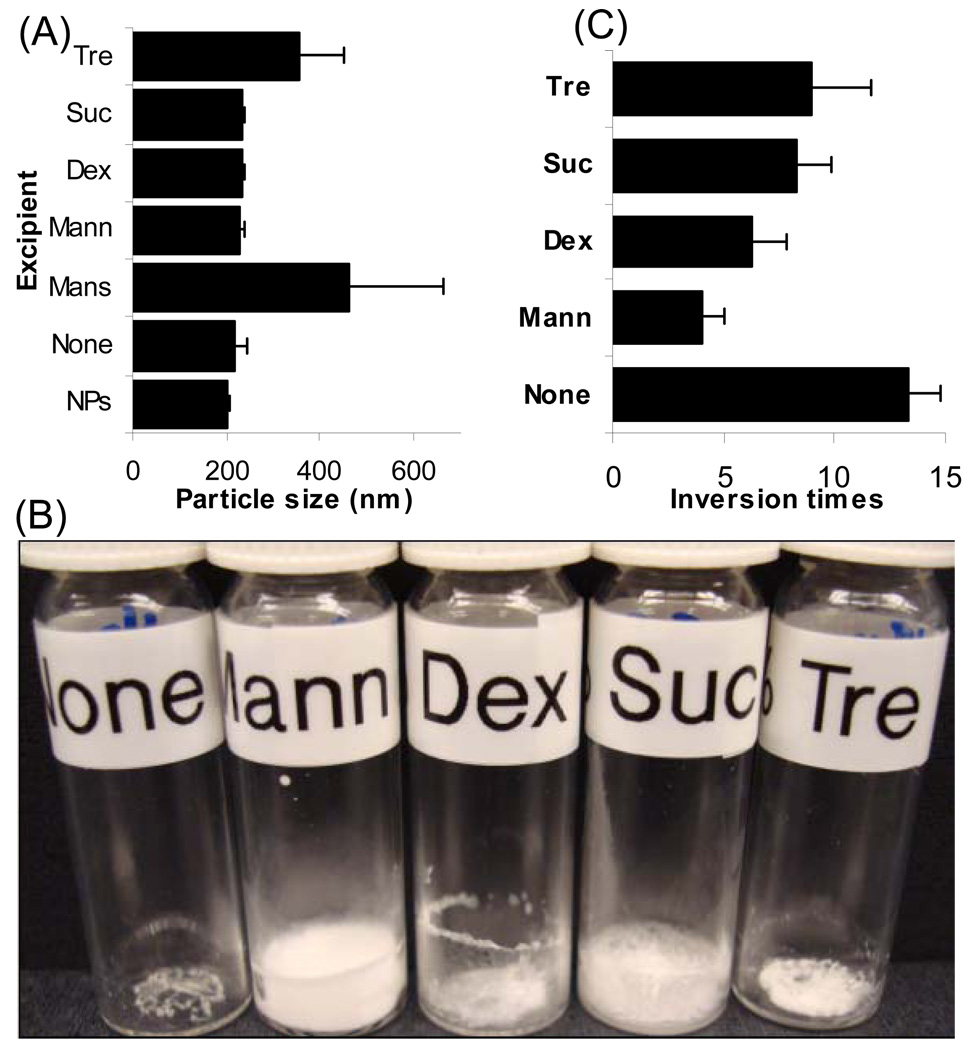

Based on previous data on the storage of protein pharmaceuticals, we hypothesized that the immunogenicity of the protein antigens conjugated onto nanoparticles can be preserved at a temperature above refrigeration if the nanoparticles are to be stored in a dried solid formulation. Therefore, we first evaluated the feasibility of lyophilizing the protein antigen-conjugated nanoparticles. BSA-conjugated nanoparticles were frozen and lyophilized using several protectants. As shown in Fig. 2A, mannitol and sucrose at 5% adequately preserved the size of the BSA-nanoparticles. The 5% was chosen because it was found to be sufficient to protect the antigen-free nanoparticles during the freezing step (Sloat and Cui, unpublished data). Although dextrose helped preserve the size of the BSA-nanoparticles, it was not further considered because it is a reducing sugar and should be avoided in the lyophilization of proteins (Wang, 2000). Interestingly, the size of the BSA-conjugated nanoparticles did not change after the lyophilization even without any protectant (Fig. 2A). It is likely that the polymeric BSA molecules conjugated on the surface of the nanoparticles helped prevent the aggregation of the BSA-nanoparticles because a proper lyoprotectant was required to successfully lyophilize the unconjugated nanoparticles (Sloat and Cui, unpublished data). However, an aesthetically appealing lyophilized cake was not formed when a lyoprotectant was not used (Fig. 2B). Only when mannitol was used, an elegant, un-collapsed cake was formed (Fig. 2B), and the cake required the fewest number of inversions to completely reconstitute (Fig. 2C). In future studies, we will examine whether the lyophilization has been placed above the collapse temperature for the formulations lyophilized with sucrose, or trehalose.

Figure 2. The lyophilization of the BSA-conjugated nanoparticles.

(A) The size of the BSA-nanoparticles lyophilized with different excipients and immediately after reconstitution with water to its original volume. The concentration of the excipient was 5% (w/v). (Suc: sucrose, Dex: dextrose, Mans: mannose, Mann: mannitol, Tre: trehalose). “None” indicates that no excipient was used. “ NPs” means the freshly prepared BSA-nanoparticles. (B) Photos of the lyophilized BSA-nanoparticles. (C) The number of inversions needed to reconstitute the lyophilized BSA-nanoparticles. Data are mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

3.3. Lyophilization of antigen-conjugated nanoparticles using mannitol (5%) and PVP (1%) as excipients did not alter the immunogenicity of the antigen

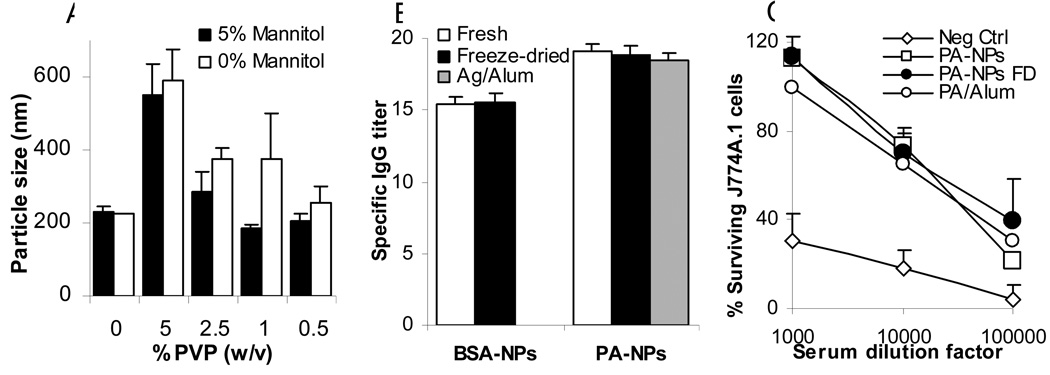

Sugars such as trehalose and sucrose with a relatively high glass transition temperature (Tg) are typically used as the primary excipient to formulate dried vaccines (Chen and Kristensen, 2009), but our data in Fig. 2 clearly showed that mannitol at 5% was optimal to lyophilize the BSA-nanoparticles. However, mannitol has a very low glass transition temperature of 11–14°C (Kim et al., 1998), making it unlikely to store the dried antigen-conjugated nanoparticles at a temperature above room temperature (22–23°C) while preserving the immunogenicity of the antigen proteins. Therefore, we tested the feasibility of including the polymeric PVP as a co-protectant to lyophilize the BSA-nanoparticles. PVP (MW 40,000) has a Tg of 160–168°C. It also has a favorable safety profile, even when injected subcutaneously or intramuscularly (La-Chapelle, 1966; Wade A, 1994). Blending it into the mannitol can potentially increase the Tg of the lyophilized powder of the BSA-nanoparticles. Moreover, in a preliminary study, we found that the inclusion of the PVP (1%) slightly, but significantly, increased the antibody responses induced by the antigen-conjugated nanoparticles lyophilized with 5% mannitol (Sloat and Cui, unpublished data). Shown in Fig. 3A was the effect of PVP at various concentrations, with and without mannitol (5%), on the size of the lyophilized BSA-nanoparticles. Reconstituted BSA-nanoparticles lyophilized with 5% mannitol and 1% PVP had a particle size most close to that of the freshly prepared BSA-nanoparticles (Fig. 3A), and thus, were chosen for further studies.

Figure 3. The lyophilization did not damage the immunogenicity of the antigens conjugated onto the surface of the nanoparticles.

(A) Lyophilization of the BSA-nanoparticles using both mannitol and PVP. (B) The lyophilized, antigen-conjugated nanoparticles (Freeze-dried) were as immunogenic as the freshly prepared ones (Fresh). BSA and protective antigen (PA) protein were used as model antigens. For the PA, a PA adsorbed onto Alum (Ag/Alum) group was included as a control. For each dosing, freshly prepared antigen-conjugated nanoparticles were lyophilized, immediately reconstituted with water to its original volume, and then injected into mice. Data are mean ± S.D. from 5 mice per group. (C) The anthrax lethal toxin neutralization activity of the serum samples from mice immunized with lyophilized/freeze-dried PA-NPs (PA-NPs FD) or freshly prepared PA-NPs. Neg Ctrl means un-immunized mice. Serum samples from mice in individual group were pooled, and the data reported were mean ± S.D. from 4 measurements.

To test whether the lyophilization step had damaged the immunogenicity of the antigen, the BSA-nanoparticles lyophilized using 5% mannitol plus 1% PVP were immediately reconstituted and used to immunize mice. As shown in Fig. 3B, the anti-BSA IgG titer induced by the lyophilized BSA-nanoparticles was not different from that induced by the freshly prepared BSA-nanoparticles. Therefore, the lyophilization step per se did not change the size of the nanoparticles, nor did it damage the immunogenicity of the antigens conjugated onto the nanoparticles.

In order to test whether the antisera induced by the lyophilized antigen-conjugated nanoparticles were still functional, we replaced the BSA antigen with the PA protein of B. anthracis. When the PA protein was used as an antigen, the neutralizing activity of the anti-PA antibodies induced can be easily measured using an in vitro anthrax lethal toxin neutralization assay (Sloat and Cui, 2006). Again, the anti-PA IgG titer induced by the lyophilized PA-nanoparticles was not different from that induced by the freshly prepared PA-nanoparticles (Fig. 3B). More importantly, the anti-PA antisera induced by the lyophilized PA-nanoparticles had a similar anthrax lethal toxin neutralization activity as those induced by the freshly prepared PA-nanoparticles, as illustrated by their ability to protect the mouse J774A.1 macrophages from the anthrax lethal toxin (Fig. 3C). Anthrax lethal toxin is comprised of the PA protein and the lethal factor protein. The PA protein is non-toxic itself, but it is required to transport the lethal factor into cells such as macrophages, and the lethal factor is toxic only when inside cells (Young and Collier, 2007) Therefore, neutralizing anti-PA antibodies can prevent the lethal factor from entering the J774A.1 macrophages and protect them from the toxicity of the lethal toxin. Apparently, the lyophilization step did not cause any detectable functional damage to the immunogenicity of the antigens conjugated onto the nanoparticles.

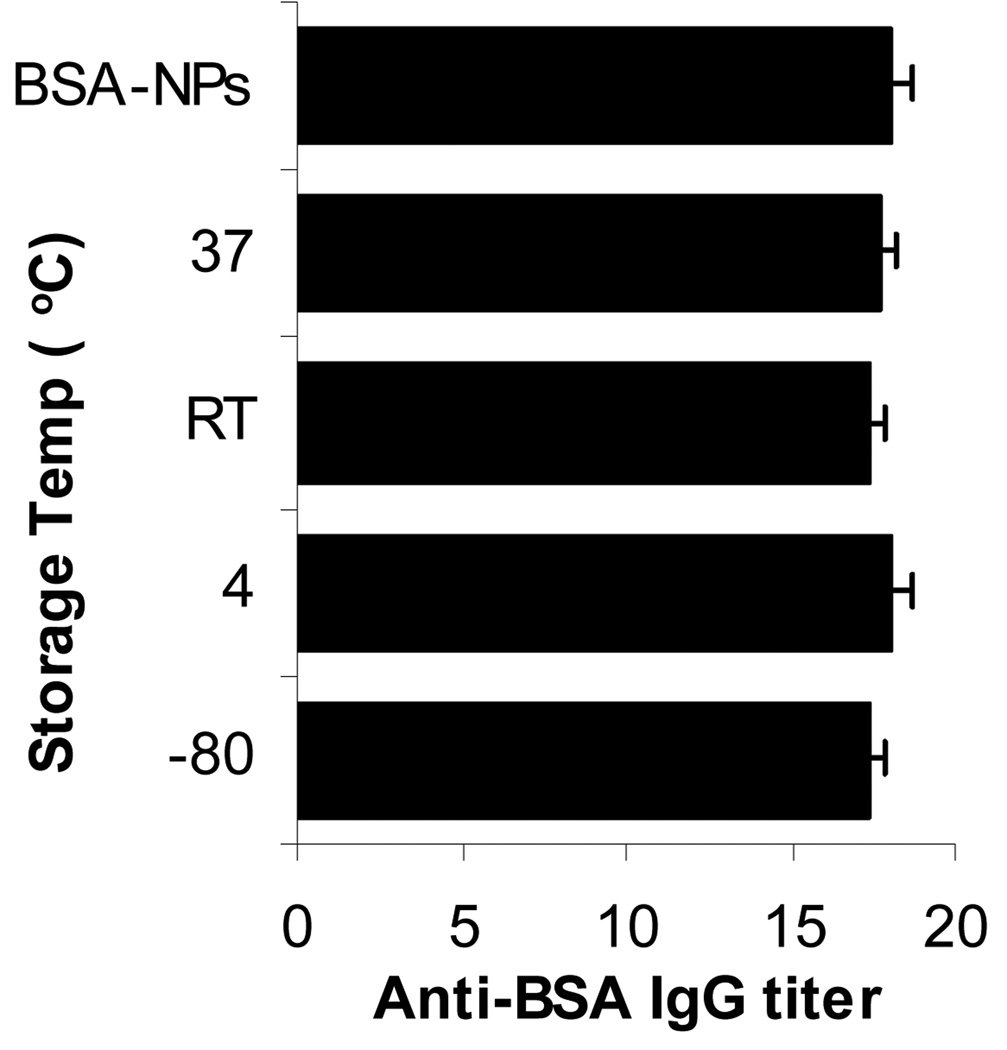

3.4. The immunogenicity of the antigens conjugated onto the nanoparticles can be potentially preserved without refrigeration

To test whether the immunogenicity of the antigens conjugated onto the surface of the nanoparticles can be potentially preserved by storing the nanoparticles in a lyophilized solid form at a temperature above refrigeration temperature, the BSA-nanoparticles lyophilized with 5% mannitol plus 1% PVP were stored at room temperature or 37°C in sealed amber vials for 2.5 months and used to immunize mice. The anti-BSA IgG titers induced by the stored nanoparticles were then compared to that induced by the freshly prepared BSA-nanoparticles. As controls, the lyophilized BSA-nanoparticles were also stored at −80°C or 4°C for 2.5 months. As shown in Fig. 4, the anti-BSA IgG titer induced by the lyophilized BSA-nanoparticles stored for 2.5 months at room temperature was not different from that induced by the freshly prepared BSA-nanoparticles. In fact, storage of the lyophilized BSA-nanoparticles at 37°C for 2.5 months also did not cause any detectable change in the immunogenicity of the BSA-nanoparticles (Fig. 4). This was probably due to the vitrification of the BSA-nanoparticles with the PVP and mannitol (Crowe et al., 1998), which resulted in a lyophilized powder with a relatively high Tg of 58–59°C, as compared to 13–14°C for the BSA-nanoparticles lyophilized in mannitol alone. A 2.5-month of storage at 37°C could be equal to about 20 months at room temperature (22°C), assuming an activation energy (Ea) value of 24.5 kcal/mol (Connors KA, 1985). Clearly, although a longer term of storage study has to be completed to confirm it, our data suggested that refrigeration can be potentially avoided while preserving the immunogenicity of the antigens conjugated onto the nanoparticles by storing the nanoparticles in a freeze-dried formulation. Although the lyophilization of nanoparticles is not new, our present study represented a successful early effort toward the development of a nanoparticle-based vaccine formulation that can be stored and distributed while avoiding the cold-chain.

Figure 4. After 2.5 months of storage at 37°C, room temperature, 4°C, or −80°C, the lyophilized BSA-conjugated nanoparticles were as immunogenic as the freshly prepared BSA-conjugated nanoparticles.

Group of mice (n = 5) were dosed 3 times every two weeks with 5 µg of BSA and bled one week after the last dosing. The BSA-nanoparticles used for each dosing were prepared separately and stored for 2.5 months before reconstitution and injection. BSA-NPs means freshly prepared BSA-conjugated nanoparticles. Data are mean ± S.D.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we showed that protein antigen-conjugated nanoparticles can be lyophilized without damaging the immunogenicity of the antigens, and that the immunogenicity of the antigens can potentially be preserved by storing the nanoparticles in a lyophilized powder form while avoiding the cold chain in vaccine storage and distribution. This approach is likely applicable to protein antigens in other nanoparticle formulations. We are planning to test the feasibility of developing an antigen-conjugated nanoparticle formulation with a shelf-life of up to 2 years at ambient temperature.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grants AI070538, AI078304, and AI065774 (to Z.C.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amorij JP, Huckriede A, Wilschut J, Frijlink HW, Hinrichs WL. Development of stable influenza vaccine powder formulations: challenges and possibilities. Pharm. Res. 2008;25:1256–1273. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9559-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter JF, Pikal MJ, Chang BS, Randolph TW. Rational design of stable lyophilized protein formulations: some practical advice. Pharm. Res. 1997;14:969–975. doi: 10.1023/a:1012180707283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang BS, Beauvais RM, Dong A, Carpenter JF. Physical factors affecting the storage stability of freeze-dried interleukin-1 receptor antagonist: glass transition and protein conformation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996;331:249–258. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Kristensen D. Opportunities and challenges of developing thermostable vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2009;8:547–557. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TG, Cassidy-Hanley D. Recombinant subunit vaccines: potentials and constraints. Dev. Biol. 2005;121:153–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors KA, Amidon GL, Stella VJ. Chemical Stability of Pharmaceuticals: A handbook for pharmacists. 2nd Ed. New York: Wiley, John & Sons, Inc.; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe JH, Carpenter JF, Crowe LM. The role of vitrification in anhydrobiosis. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1998;60:73–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z, Lockman PR, Atwood CS, Hsu CH, Gupte A, Allen DD, Mumper RJ. Novel D-penicillamine carrying nanoparticles for metal chelation therapy in Alzheimer's and other CNS diseases. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2005;59:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z, Qiu F, Sloat BR. Lecithin-based cationic nanoparticles as a potential DNA delivery system. Int. J. Pharm. 2006;313:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim AI, Akers MJ, Nail SL. The physical state of mannitol after freeze-drying: effects of mannitol concentration, freezing rate, and a noncrystallizing cosolute. J. Pharm. Sci. 1998;87:931–935. doi: 10.1021/js980001d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La-Chapelle J. Thesaurismose cutanee par polyvinylpyrrolidone. Dermatologica. 1966;132:476–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrie Y, Mohammed AR, Kirby DJ, McNeil SE, Bramwell VW. Vaccine adjuvant systems: enhancing the efficacy of sub-unit protein antigens. Int. J. Pharm. 2008;364:272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy ML, Pikal MJ, Rickard EC, Maloney AM. The effects of formulation and moisture on the stability of a freeze-dried monoclonal antibody-vinca conjugate: a test of the WLF glass transition theory. Dev. Biol. Stand. 1992;74:323–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackell L. An improved method of desiccation, with some applications to biological problems. Am. J. Physiol. 1909;24:325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Chakrapani A, O'Hagan D. Nanoparticles and microparticles as vaccine-delivery systems. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2007;6:797–808. doi: 10.1586/14760584.6.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloat BR, Cui Z. Nasal immunization with a dual antigen anthrax vaccine induced strong mucosal and systemic immune responses against toxins and bacilli. Vaccine. 2006;24:6405–6413. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloat BR, Sandoval MA, Hau AM, He Y, Cui Z. Strong Antibody Responses Induced by Protein Antigens Conjugated onto the Surface of Lecithin-Based Nanoparticles. J. Control. Release. 2010;141:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade A, Weller PJ. Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients. 2nd Ed. London: The Pharmaceutical Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. Lyophilization and development of solid protein pharmaceuticals. Intl. J. Pharm. 2000;203:1–60. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(00)00423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanasarn N, Sloat BR, Cui Z. Nanoparticles engineered from lecithin-in-water emulsions as a potential delivery system for docetaxel. Intl. J. Pharm. 2009;379:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JA, Collier RJ. Anthrax toxin: receptor binding, internalization, pore formation, and translocation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:243–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]