Abstract

Intrinsically fluorescent proteins (FPs) exhibit broad variations of absorption and emission colors and are available for different imaging applications. The physical cause of the absorption wavelength change from 540 nm to 590 nm in the Fruits series of red FPs has been puzzling because the mutations that cause the shifts do not disturb the π-conjugation pathway of the chromophore. Here we use two-photon absorption measurements to show that the different colors can be explained by quadratic Stark effect due to variations of the strong electric field within the beta barrel. This model brings simplicity to a bewildering diversity of fluorescent protein properties, and it suggests a new way to sense electrical fields in biological systems.

The initial cloning and characterization of the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) (1,2) soon led to the mutants that produce blue, cyan and yellow fluorescent proteins (FPs) (3). These are powerful genetically-encoded tools for imaging living cells and tissues. The first protein fluorescing in the red part of the spectrum (DsRed) was discovered more recently (4), and many different hues of red fluorescent proteins (RFPs) now exist (5). The most widely used RFPs are the Fruit series (6,7), and they are particularly well suited for deep tissue and multicolor imaging. Although it is clear that different chromophore structure (e. g. in GFP versus DsRed) will result in different absorption wavelengths (8), the large spectral shifts (up to ~50 nm) observed in the Fruit series are due to mutations in the staves of the beta barrel that surround the RFP chromophore and do not disturb its conjugation pathway (see crystallography data (9–12)). How can only a few such perturbations produce dramatic changes in the chromophore optical properties?

Shu et al. (10) suggested that the red shifts of absorption peaks in mStrawberry and mCherry, compared to DsRed, are due to amino acid substitutions that result in rearrangements of hydrogen bonds, and redistribution of charges, close to the chromophore. This can cause the perturbation of local electric field inside the protein. In other FP series, where the mutations do not disturb the chromophore conjugation pattern, spectral shifts are also thought to arise from changes in local electrostatic interactions between the chromophore and surrounding (13–15). Despite these indications that electrostatics can play an important role in color variations, there are no direct measurements of the intrinsic electric field deep in the protein structure, and the physical picture of the effect remains unclear.

Here we introduce a new all-optical approach that enables us to directly measure the electric field inside a protein and rationalize the puzzling color changes in the Fruit series. Suppose the permanent dipole moment in the chromophore excited state (μ e) is different from that in the ground state (μ g), resulting in non-zero value of Δμ = μe − μg. Then, provided that there is a local electric field inside the protein matrix, the internal Stark effect may produce a shift of the chromophore absorption maximum relative to the value in the absence of a field. Note that since the internal field originates from the protein beta barrel, its direction is fixed with respect to chromophore orientation. Therefore, the Stark shift will be the same for all protein particles regardless of their macroscopic (e. g. isotropic) arrangement in the sample. The amplitude, direction, and gradient of the field could be tuned by changing the charge on certain residues or altering the hydrogen-bond and salt bridge network in the chromophore surrounding. Furthermore, if the polarizability tensor of the chromophore α has substantially large components, then a strong local electric field E will create an additional, induced, permanent dipole moment on the chromophore. The intrinsic (vacuum) dipole moment difference between the excited and the ground states Δμ 0 is superimposed with the induced value, Δμ ind (Δμ ind = ΔαfS E, where Δα is the difference of polarizabilities in these states and fS is the static local field factor). If the absolute values of Δμ ind are rather large, then the absorption frequency will depend quadratically on the electric field (second order, or quadratic Stark effect).

A first order Stark effect has been observed in some FPs (16–18). Using Stark spectroscopy, Boxer, Moerner, and co-authors have found that in RFPs, Δμ =|Δμ| = (5 – 7 D)/fS, and that a uniform external electric field of the order of 1 MV/cm only produces a linear Stark effect (17,19). This field strength was probably not large enough to create any additional induced dipole moment difference of the absolute value similar to Δμ. The internal electric field of a protein may be much stronger than the typical values of external field that can be potentially applied, i.e., up to 10 – 80 MV/cm (19–21). In these varying field strengths corresponding to a series of different proteins, Callis and co-workers have shown that the tryptophan fluorescence peak exerts a virtually linear internal Stark shift (20) probably because of relatively small Δα components of tryptofan. On the other hand, a large change of induced dipole moment due to protein environment has been shown for spheroidene in photosynthetic antenna complex (22), which is consistent with a quadratic Strak effect.

The strong internal electric fields necessary to produce quadratic Strak effect in proteins were previously predicted theoretically (20,23) or estimated from the hole burning experiments by using quantum-mechanically assessed values of Δα (17, 19). However, full-experimental access to these fields has yet to be realized. We have recently shown (24) that the value of Δμ in the GFP chromophore can be determined experimentally by measuring the 2PA cross section in the maximum of the pure electronic (0–0) transition. In combination with the absorption peak shift, Δμ can then be used as an accurate metric of the local internal field within a protein. Here, we apply this approach to a series of red FPs, derived from DsRed.

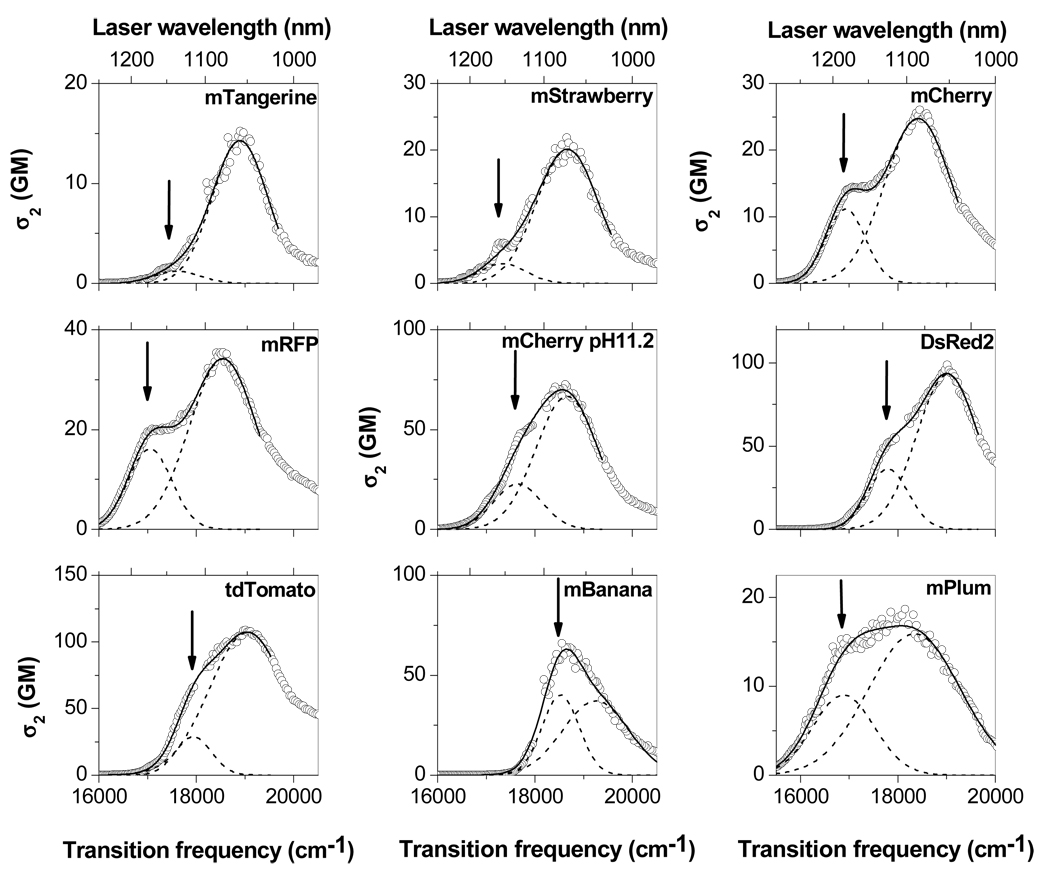

Figure 1 shows the 2PA spectra of the Fruit series. DsRed2 (25), mRFP (26) and mCherry at pH11.2 (10) are also included. All the proteins show the 2PA band in the region 1000 – 1200 nm which corresponds to the first electronic, S0 → S1 transition (27). The maximum of the 2PA band can be assigned to a vibronic, 0–1, transition (27). The weaker 2PA 0–0 transition appears as a low-frequency shoulder. To obtain the σ2(0–0) value, we fit the 2PA spectrum in the main part of the S0 → S1 band with a sum of two Gaussians. The fitting was performed with the fixed frequency of the 0–0 transition, marked by an arrow and set equal to the one-photon absorption 0–0 transition frequency, and with variable frequency of the vibronic, 0–1 transition. (Several other methods of multi-Gaussian fits were also explored and gave similar results, see Supplementary Materials.) The Δμ values for all the proteins were obtained within the two-level approximation of 2PA transition, by using the σ2(0–0) values and maximum extinction coefficients, ε(0–0) (28), as follows (See Supplementary Materials for more details):

| (1) |

where h is the Planck’s constant, c is the speed of light, NA is the Avogadro number, n is the refractive index of the medium (n = 1.33), ν̄0–0 is the central frequency of the 0–0 transition (in cm−1), γ is the angle between Δμ and transition dipole moment μ, fopt is the local field factor at optical frequency. The results are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Two-photon absorption spectra of a series of red FPs in the region of the first electronic transition. 2PA cross section σ2 (in GM, 1GM = 10−50 cm4 s) is plotted versus transition frequency (equal to twice the laser photon frequency). Laser wavelength used for excitation is shown as a top x-axis. The fit with a sum of two Gaussians is shown with continuous line. Individual Gaussians are shown by dashed lines. An arrow depicts the 0–0 1PA transition frequency which was kept fixed upon fitting of 2PA spectra.

Table 1.

Optical properties of a series of red fluorescent proteins. Unless otherwise stated, all the data are presented for pH 8 buffer solutions. ν(0–0) is the maximum of pure electronic S0 → S1 transition; εmax(0–0) is the extinction coefficient at this frequency; σ2(0–0) is the two-photon absorption cross section at ν(0–0), obtained as described in the text and measured in GM (1 GM = 10−50 cm4 s); Δμ is the absolute value of the difference between the permanent dipole moment in the excited (S1) and the ground (S0) state, measured in Debye (D); Δμind is the projection of induced dipole moment difference (between S1 and S0) on Δμ0, fS E is an effective local electric field projection on Δμ 0, fS is the local field factor.

| Protein | ν(0–0) (cm−1) |

εmax(0–0) (103 M−1 cm−1) |

σ2(0–0) (GM) |

Δμ (D) |

Δμind (D) |

fSE (MV/cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mTangerine | 17634 | 33.5 | 1.1 | 1.0 | −7.0 | 102 |

| mStrawberry | 17295 | 40.8 | 2.7 | 1.41 | −6.2 | 90 |

| mCherry | 16925 | 61.8 | 11 | 2.22 | −4.5 | 66 |

| mPlum | 16882 | 37.5 | 9.0 | 2.55 | −3.9 | 57 |

| mRFP | 17006 | 54.2 | 15 | 2.75 | −3.5 | 51 |

| mCherry pH 11.2 | 17685 | 51.7 | 22 | 3.48 | −2.0 | 29 |

| DsRed2 | 17760 | 77.1 | 34 | 3.55 | −1.9 | 28 |

| tdTomato | 17950 | 58.7 | 28 | 3.73 | −1.5 | 22 |

| mBanana | 18457 | 64.1 | 40 | 4.04 | −0.9 | 13 |

The change of permanent dipole moment was previously measured for some of these red fluorescent proteins using Stark spectroscopy (17,18). For wt-DsRed, the authors found |Δμ| fS = 7.0 D (17), for mRFP: |Δμ| fS = 6 ± 1 D (18), and for mPlum |Δμ| fS = 5 ± 1 D (18). If we compare our results for DsRed2 (|Δμ| = 3.55 D), mRFP (|Δμ| = 2.75 D), and mPlum (|Δμ| = 2.55 D) with these values (29), we notice that for all three proteins |Δμ| fS values are systematically larger by a factor of 2 than |Δμ|, and therefore, fS ≈ 2. Assuming that in protein solutions fS value is determined mostly by the local protein matrix around the chromophore, but not the bulk solvent (30), and using Lorentz model, fS = (ε +2)/3, we find that the interprotein effective dielectric constant, ε = 4. This value falls well within the limits, usually accepted for modeling protein interiors, ε = 2 – 4 (31).

Inspection of Table 1 also reveals that Δμ increases dramatically in the series, starting from 1 D in mTangerine and reaching 4 D in mBanana. This increase implies that there must be sizable variations of induced dipole moment from one FP to the next, which are directly related to the large changes of E.

Let ν0 be the pure electronic transition frequency of the chromophore in vacuum (i.e. for a hypothetical case of the chromophore experiencing no electrostatic interactions with the surrounding); Δμ 0 be the difference of vectors of permanent dipole moments in the excited and the ground states in vacuum; and Δα 0 be the difference between the corresponding tensors of polarizability in vacuum. Let us define an effective electric field that is created by all types of electrostatic interactions (long-range Coulomb, short range dipole-dipole, hydrogen-bonding, etc.) at the chromophore site as E, varying from one mutant to another. Then the absorption transition energy of a chromophore in protein environment can be presented in point dipole approximation as (see e.g. (32)):

| (2) |

where

| (3) |

The second term in (3) is, by definition, one-half of the induced dipole moment difference. At this point, we can substitute the unknown electric field in (2) with the Δμ by re-arranging Eq. (3) (cf. ref. (33)):

| (4) |

where (Δα 0)−1 is the matrix inverse to Δα 0. This gives:

| (5) |

Now suppose that Δα 0 has a major component only along the direction of Δμ 0, i.e. Δα0 can be considered as a scalar Δα0. This assumption is quite common for charge-transfer chromophores with Δμ0 ≳ 1 D (33, 34 and references therein), is also supported by our data on 2PA isotropic polarization ratio presented in SI, and also justified by recent quantum-chemical calculations on a model red chromophore (35), implying that Δμ 0, Δμ ind and Δμ vectors are either parallel or antiparallel to each other. Taking this into account, and converting frequency into wavenumbers, we obtain:

| (6) |

This equation is an alternative representation (with respect to standard (2) and (3)) of the second order internal Stark effect.

In Figure 2 we plot the frequency of the 1PA 0–0 transition of the Fruit FPs series as a function of Δμ. The dependence fits very well with a parabola: y = A + Bx + Cx 2. Comparing the best-fit coefficients with their expressions in (6), we obtain the following parameters of the red chromophore: ν̄0 = (19350 ±120) cm −1, Δμ0 = (4.49 ± 0.27) D (where Δμ0 is the projection of Δμ 0 on Δμ), and Δα0 = (− 20.6 ± 0.8) Å3. Nifosi et al. (8) calculated the vacuum transition frequency of DsRed chromophore, ν̄0 = 19030 cm −1, using TDDFT with GB-B3LYP functional, and, vacuum Δμ0 = 4.69 D with BLYP functional. Both our experimental values correlate perfectly with the theoretical results. The Δα0 tensor was calculated in (35) for a model 4-hydroxy-benzylidene-1-methyl-2-propenyl-imidazolinone red chromophore, and it was found that Δα0 has a main component along one selected axis, equal to Δα0 = − 15 Å3. This result is similar to our experimental value both in amplitude and sign. These rather good correlations between experimental and calculated values help to justify our initial assumption on the applicability of two-level approximation for the 2PA transition.

Figure 2.

Dependence of the pure electronic S0 → S1 transition frequency (which is very close to 1PA maximum) on permanent dipole moment difference between S1 and S0 states for a series of red FPs. Top x-axis shows the projection of effective electric field on the direction of Δμ 0. fS is the local field factor. Continuous line shows the best fit with second order polynomial: y = A + Bx + Cx 2 with the coefficients A = 19350 ± 116 cm−1, B = − 2180 ± 100 cm−1 D−1, C = 486 ± 20 cm−1 D−2. The inset shows the chromophore structure. Note that the crystal structures, available for DsRed (9), mStrawberry (10), mCherry (10), mPlum (11), and mBanana (12), show that the chromophore is the same for these five proteins and contains the acylimine group. For the remaining four proteins, there are strong indications that the chromophore structure is the same as shown. It is known that the originally produced acylimine tail of the DsRed-type chromophore can be attacked by either –OH group of Thr66 or –SH group of Cys66, to produce new chromophores in mOrange (10) and mKO (34), respectively. For this reaction to occur Glu215 should be deprotonated and, in the case of Cys66, position 70 should be occupied by Arg, not Lys. mRFP is a product of DsRed with no mutations in close proximity to the chromophore, including position 66. mRFP is also a progenitor for mCherry and mStrawberry, which both have the same chromophore as DsRed. tdTomato and mCherry (at pH11.2) have Q66M mutation, which should not have nucleophilic activity. mTangerine, similarly to mBanana holding intact acylimine tail, possesses Q66C mutation, but has Lys in position 70.

Several important conclusions stem from Fig. 2. First, one can see that there is a limiting minimum absorption frequency, equal to ν̄ =16900 cm −1 (longest possible wavelength of 0–0 transition, 592 nm), that virtually corresponds to both mCherry and mPlum. In other words, no mutations in the barrel structure can further red-shift this chromophore absorption. Second, we find that Δα0 is negative, which means that the polarizability of the chromophore in the excited state is less than in the ground state. The sign of Δα0 defines the direction of Δμ ind if the direction of electric field is given. Also, the negative sign of the linear term in the parabolic fit in Fig. 2 implies that the dot product (Δμ 0 • Δμ) is positive, and therefore vector Δμ is co-directed with vector Δμ 0. But since in the studied region |Δμ| < |Δμ 0|, we conclude that Δμ ind is directed oppositely to Δμ 0.

For the practical reasons, if one would like to further increase Δμ (e.g. for enhancing two-photon absorption or for improving the sensitivity of probing an electric field), one would need to create a mutant where the internal electric field vector will be oriented in the opposite direction to the one found in the Fruits. Such change will, however, inevitably cause a blue shift of the absorption maximum.

Knowing Δμ0 and Δα0, and using Δμ values presented in Table 1, we can now estimate, using (3), the effective local field at the chromophore site fSE (more exactly - projection of the field vector on Δμ 0). The obtained values of the field strength vary from 10 to 100 MV/cm (Table 1), which is well in the range of previous theoretical estimations for myoglobin (19), cytochrome c (21), calmodulin (20), cone opsins (37), and other proteins (20). To our knowledge, this is the first time that internal field of a protein is measured experimentally. It is also instructional to compare these values to other electric fields encountered in biological systems. For example, the field change across the membrane of a neuron during the action potential is about two orders of magnitude smaller, ~ 0.3 MV/cm. On the other hand, the field binding an electron to the GFP chromophore (corresponding to ionization potential) is still about 1 – 2 orders of magnitude higher (38) than the intraprotein field.

In conclusion, the differences in hue in the Fruit series of red FPs are caused by a quadratic Stark effect exerted on the chromophore by the protein environment. The knowledge of the mechanism of color tuning in FPs, and direction of permanent dipole difference, will facilitate rational design of new mutants with desired optical properties, including improved field sensitivity, two-photon brightness, or absorption/emission wavelength. The internal Stark effect likely tunes the absorption of other FPs and chromoproteins as well. For example, electrostatic interactions in the human color opsins are thought to tune the absorption properties of retinal (39). The experimental approach and physical model proposed here may also provide useful insights into other protein realms, such as enzymatic activity and folding processes. Other all-optical methods interrogating two-photon transitions, such as resonance hyper-Raman and hyper-Rayleigh spectroscopies (40) can potentially provide an access to Δμ (and, therefore, internal electric fields) if a weakly- or non-fluorescing chromophore is used as a probe.

It appears that the striking beauty of a coral reef, both in the variety of colors it contains and the way we perceive them, involves the effects of strong electric fields occurring within a nanoscopic protein environment: both the opsin proteins in the eye of the beholder and the beta-barrel of the fluorescent proteins shape perception through Stark effect.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIGMS grant 1 R01 GM086198-01. We thank Prof. R. Tsien for providing us the DNA of the Fruit series and Prof. P. R. Callis for useful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Methods of expression and purification of proteins, measurement of mature chromophore concentration, evaluation of Δμ from 2PA spectra, multi-Gaussian fits of 1PA and 2PA spectra, estimation of errors in Δμ due to different methods of fitting of 2PA spectra, estimation of statistical reliability of parabolic fitting curves and the errors in chromophore parameters. This information is available free of charge via Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References and notes

- 1.Prasher DC, Eckenrode VK, Ward WW, Prendergast FG, Cormier MJ. Gene. 1992;111:229. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90691-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC. Science. 1994;263:802. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsien RY. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998;67:509. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matz MV, Fradkov AF, Labas YA, Savitsky AP, Zaraisky AG, Markelov ML, Lukyanov SA. Nat. Biotech. 1999;17:969. doi: 10.1038/13657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaner NC, Patterson GH, Davidson MW. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:4247. doi: 10.1242/jcs.005801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaner NC, Campbell RE, Steinbach PA, Giepmans BNG, Palmer AE, Tsien RY. Nat. Biotech. 2004;22:1567. doi: 10.1038/nbt1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L, Jackson WC, Steinbach PA, Tsien RY. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:16745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407752101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nifosi R, Amat P, Tozzini V. J. Comput. Chem. 2007;28:2366. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross LA, Baird GS, Hoffman RC, Baldridge KK, Tsien RY. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:11990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shu X, Shaner NC, Yarbrough CA, Tsien RY, Remington SJ. Biochem. 2006;45:9639. doi: 10.1021/bi060773l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shu X, Wang L, Colip L, Kallio K, Remington SJ. Protein Science. 2009;18:460. doi: 10.1002/pro.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.mBanana contains the same chromophore as DsRed, personal communication by Dr. Xiaojian Hu, Fudan University, Shanghai, China; Zhou Y, Wu Y, Song J, Ding Y, Hu X, Zhang Z. Protein and Peptide Lett. 2008;15:113. doi: 10.2174/092986608783330341.

- 13.Wachter RM, Elsliger MA, Kallio K, Hanson GT, Remington SJ. Structure. 1998;6:1267. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson JN, Remington SJ. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:12712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502250102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ai HW, Olenych SG, Wong P, Davidson MW, Campbell RE. BMC Biol. 2008;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bublitz G, King BA, Boxer SG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:9370. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lounis B, Deich J, Rosell FI, Boxer SG, Moerner WE. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:5048. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abbyad P, Childs W, Shi XH, Boxer SG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:20189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706185104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geissinger P, Kohler BE, Woehl JC. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1995;99:16527. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callis PR, Burgess BK. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1997;101:9429. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manas ES, Wright WW, Sharp KA, Friedrich J, Vanderkooi JM. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000;104:6932. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gottfried DS, Steffen MA, Boxer SG. Science. 1991;251:662. doi: 10.1126/science.1992518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vivian JT, Callis PR. Biophys. J. 2001;80:2093. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76183-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drobizhev M, Makarov NS, Hughes T, Rebane A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:14051. doi: 10.1021/jp075879k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yanushevich YG, Staroverov DB, Savitsky AP, Fradkov AF, Gurskaya NG, Bulina ME, Lukyanov KA, Lukyanov SA. FEBS Lett. 2002;511:11. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell RE, Tour O, Palmer AE, Steinbach PA, Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:7877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082243699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drobizhev M, Tillo S, Makarov NS, Hughes TE, Rebane A. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:855. doi: 10.1021/jp8087379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Note that similar approach was originally used to obtain Δμ in Birge R, Zhang C-F. J. Chem. Phys. 1990;92:7178.

- 29.Assuming that minor periphery mutations in DsRed2 do not change the |Δμ| in wt-DsRed and also that local field factor is the same for all proteins.

- 30.Bublitz GU, Boxer SG. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1997;48:213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.48.1.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen BE, McAnaney TB, Park ES, Jan YN, Boxer SG, Jan LY. Science. 2002;296:1700. doi: 10.1126/science.1069346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berlin Y, Burin A, Friedrich J, Kohler J. Physics of Life Rev. 2006;3:262. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vauthey E, Holliday K, Wei CJ, Renn A, Wild UP. Chem. Phys. 1993;171:253. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bublitz G, Ortiz R, Marder SR, Boxer SG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:3365. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan W, Zhang L, Xie D, Zeng J. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:14055. doi: 10.1021/jp0756202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kikuchi A, Fukumura E, Karasawa S, Mizuno H, Miyawaki A, Shiro Y. Biochem. 2008;47:11573. doi: 10.1021/bi800727v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathies R, Stryer L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1976;73:2169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.7.2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hasegawa J-Y, Fujimoto K, Swerts B, Miyahara T, Nakatsuji H. J. Comput. Chem. 2007;28:2443. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujimoto K, Hasegawa J-Y, Nakatsuji H. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2008;462:318. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shoute LCT, Blanchard-Desce M, Myers Kelley A. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2005;109:10503. doi: 10.1021/jp0545851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.