Abstract

Altered DNA methylation is a fundamental characteristic of carcinogenesis. The analysis of DNA methylation in tumor cells may help to better understand tumor pathogenesis and more importantly may be used as diagnostic tool with therapeutic consequences. To detect targets relevant in tumorigenesis, it is essential to separate neoplastic cells from nonneoplastic cells. An excellent method for isolating specific cells is laser-assisted microdissection (LAM). Target cell identification for immunoguided LAM (ILAM) requires immunohistochemistry (IHC). Yet, it is unclear whether IHC for ILAM influences DNA methylation. The goals of this study were to establish an optimized protocol for antigen retrieval and IHC of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) specimens suitable for ILAM and to evaluate its effect on the DNA methylome using a high throughput array. Using ten archival FFPE specimens, we showed specific staining suitable for ILAM. Extracted DNA from microdissected cells of immunohistochemically or H&E-stained tissue sections showed identical DNA quality and a strong correlation (r = 0.94 to 0.98) for CpG target methylation of 1505 analyzed sites in a series of five paired samples. No differential methylation between H&E and IHC was detected in 1501 of 1505 CpG targets (99.7%; P < 0.05). These results demonstrate the validity and utility of the herein described protocol, which allows the application of ILAM for large-scale genomic and epigenetic analyses of archival tissue specimens.

Epigenetics is defined as the study of heritable changes in gene expression that are not attributable to alterations in the DNA sequence.1 The best-known epigenetic marker is DNA methylation. DNA methylation plays an important role in the control of gene activity and the architecture of the nucleus.2 During carcinogenesis, DNA of tumor cells is characterized by hypomethylation in gene regions that promote tumor development, whereas hypermethylation occurs among tumor suppressor genes.3,4 Especially for large-scale analysis of cancer tissue methylation, it is important to investigate the tumor cells and not the intermixed inflammatory cells or other normal host cells to identify targets relevant in tumorigenesis. Therefore, laser-assisted microdissection (LAM) is a helpful tool to isolate cell populations for cell-specific molecular profiling.5 Typically, the identification of target cells relies on morphological cell characteristics observed after routine histological staining. The gold standard for histopathological diagnosis is hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining.6 However, depending on the type of tissue and the cells of interest, H&E staining may be inadequate for a clear identification of some cell types. Optical resolution is especially impaired when using the LAM scope, because LAM is not compatible with use of a cover slide and selection of cells with less distinct morphological characteristics can be hampered under these conditions. In cases where routine staining does not allow discrimination between normal and pathological cell morphology, visualization of cell surface or intracellular structures can be helpful. For example, labeling of cellular proteins by immunohistochemistry (IHC) can assist in identification of specific target cells. The application of IHC to LAM, also called immunoguided LAM (ILAM), is a valuable technique that allows localization of target cells and microdissection of particular cell populations. In addition, IHC enables the use of automatic cell recognition programs included in the advanced series of LAM instruments. By using LAM devices with automatic cell recognition programs it is technically feasible to collect high numbers of target cells in a reasonable time.7

Currently antigen retrieval (AR) and IHC on positively charged glass slides is a widely established method in routine pathology laboratories. The original laser capture microdissection system was based on an infrared (IR) laser that captured the cells of interest from tissue sections mounted on glass slides.5 However, all current microdissection systems incorporate an UV cutting laser that is not suitable for positively charged glass slides but requires special polyethylene naphthalate (PEN) membrane slides. IHC on membrane slides, particularly common AR procedures required for formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue samples, usually result in loss of parts of the tissue or the entire tissue section. For that reason regularly used AR methods at high temperature (90°C) are not suitable for ILAM. More importantly, it is unclear whether IHC for ILAM influences DNA integrity or DNA methylation of target cells from archival tissue samples. The goals of this study were to establish an optimized protocol for AR and IHC of FFPE tissue samples suitable for ILAM and to determine whether the DNA methylation profile is affected by AR or IHC. For establishing this protocol, we selected FFPE specimens from primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMLBCL) as well as cases of classical Hodgkin's lymphoma (CHL), the latter representing a model of a highly challenging LAM.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Samples

For our studies we used FFPE tissue samples from the archives of the Laboratory of Pathology at the National Institutes of Health. All cases were anonymized and identifiers removed; therefore, cases were exempted from Institutional Review Board approval. Five cases with PMLBCL and five cases with CHL, nodular sclerosis subtype (CHLNS), were chosen to establish the immunohistochemical staining protocols for CD20 and CD30.

Slide and Tissue Processing

PEN membrane glass slides (MDS Analytical Technologies, Sunnyvale, CA, catalog # LCM0522) were irradiated with UV light at 254 nm for 60 minutes as stated (PALM Microlaser Systems, Los Angeles, CA). During UV irradiation, the membrane was faced upwards with a 5-cm distance between the UV light source and the slide. After UV treatment each slide was coated with 350 μl of undiluted poly-L-lysine 0.1% w/v (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, catalog # P8920). For drying, the slides were placed in a slide holder for 60 minutes at room temperature. Five-micrometer tissue sections were cut in a microtome (Leica RM2255 rotary microtome, Wetzlar, Germany) using low profile steel blades. The sections were mounted on the pretreated membrane slides as routinely done using glass slides but without a coverslip and without standard mounting medium. After mounting the tissue sections, the membrane slides were incubated at 60°C for 2 hours in a dry oven to further improve tissue adhesion to the membrane. Deparaffinization was performed in fresh xylenes for 7 minutes, and this step was repeated three times using staining trays with fresh solutions. This process was followed by prolonged washing and hydration in ethanol solutions: four times for 5 minutes using fresh 100% ethanol, two times for 5 minutes in fresh 95% ethanol, and a final step of 5 minutes in fresh 70% ethanol.8 Subsequently, the slides were transferred into distilled water.

Antigen Retrieval

Two different types of AR were evaluated for IHC of FFPE samples mounted on PEN membrane slides.

Antigen Retrieval with Pepsin

For the AR with pepsin we used Dako Pepsin (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark, catalog # S3002). The reagents were prepared according to the manufacturer's instruction, and the pepsin solution was prewarmed to 37°C before usage. We compared AR in a vertical pepsin bath using a glass Coplin staining jar versus pipetting the pepsin directly onto the horizontal slide. In the latter case the membrane and the tissue were faced upwards, and the area of AR was marked with a Dako Pen (catalog # S2002) before adding the pepsin directly onto the area. The slide was incubated with the Pepsin solution in an oven at 37°C. We compared both methods and different incubation times (10, 15, 20 minutes).

Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval

Because common heat induced epitope retrieval (HIER) procedures at high temperature (90°C) may affect tissue and membrane integrity, AR with HIER was performed at lower temperature (60°C). We compared Dako Target Retrieval Solution (catalog # S1700) and DakoCytomation Target Retrieval Solution, pH9 (catalog # S2368). Retrieval solutions were prewarmed to 60°C before usage. The slides were put vertically in a rectangular staining jar for AR and different incubation times (16, 24, 42, 48 hours) were examined.

Immunohistochemistry

After incubation in the oven, we let the AR solution cool down to room temperature and the slides were transferred into distilled water. For IHC we used Dako EnVision+ System-HRP diaminobenzidine (DAB) (catalog # K4007) and the following primary antibodies: Dako monoclonal mouse anti-human CD20cy clone L26 (catalog # M0755) and Dako monoclonal mouse anti-human CD30 clone Ber-H2 (catalog # M0751).

Endogenous peroxidases were blocked with peroxidase block solution [Dako EnVision+ System-HRP (DAB), catalog # K4007] for 10 minutes, washed in fresh distilled water for 30 seconds and placed in fresh 1× PBS, pH 7.4 for 1 minute. The primary antibody was applied and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes in a humidifying chamber. In our studies we compared different dilutions of the primary antibody for CD20 and CD30. For dilution of the primary antibody we used Dako Antibody Diluent with Background Reducing Components (catalog # S3022). The dilutions we compared ranged from 1:20 to 1:50 for CD30 and from 1:200 to 1:400 for CD20. Before adding the secondary antibody, slides were washed twice in fresh PBS, pH 7.4 each for 30 seconds. The secondary antibody, labeled polymer-HRP anti-mouse [Dako EnVision+ System-HRP (DAB), catalog # K4007], was applied for 30 minutes. After incubation with the secondary antibody, slides were washed two times in fresh 1× PBS pH 7.4 for 30 seconds each time. Chromogenic labeling was performed with 3,3′-DAB+ substrate buffer and DAB+ chromogen [Dako EnVision+ System-HRP (DAB), catalog # K4007] for 5–10 minutes. Slides were washed in fresh distilled water for 30 seconds. DAB enhancer (catalog # S1961) was applied for 2 minutes. Slides were washed in fresh distilled water for 30 seconds. After IHC, sections were optionally counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, catalog # MHS32-1L) (60 seconds), distilled water (20 seconds), and blueing (30 seconds). Dehydration was performed as follows: 70% ethanol for 15 seconds, 95% ethanol for 20 seconds, 100% ethanol for 20 seconds, and xylenes for 20 seconds.

Microdissection and DNA Extraction

For our study, microdissection of tumor cells was performed using the Leica LMD 6000. In addition, we evaluated the mode of operation of three conventional microdissecting systems that are currently available: Arcturus XT (MDS Analytical Technologies, Sunnyvale, CA), Leica LMD 6000 (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), and PALM MicroBeam (P.A.L.M. Microlaser Technologies AG, Bernried, Germany).

DNA from microdissected tumor cells was extracted with QIAamp DNA Micro Kit (catalog # 56304) according to the manufacturer's instruction. For the Illumina GoldenGate Methylation assay, tissue lysis and DNA extraction were performed using 40 μl Buffer ATL (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, catalog # 19076), 5 μl Proteinase K (Qiagen, CA, catalog # 19131), and 4 μl Dako Target Retrieval solution High pH 10× Concentrate (catalog # S3307) per sample. Incubation time was 16 hours at 65°C. DNAs were bisulfate modified using EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research, CA, catalog # D5005) according to the manufacturer's instruction. The quantity of the extracted DNA of H&E-stained tumor cells or immunohistochemically stained tumor cells was measured with NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer.

PCR and Illumina GoldenGate Methylation Array

Adequacy of the obtained DNA for further investigations was tested by PCR amplification using three different sets of primers that all target the β-globin gene but produce three specific amplicons of increasing size: 152 bp, 268 bp, and 676 bp. PCR of β-globin gene was performed as described before.9 The amplified products were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and detected by UV transillumination.

250 ng of bisulfite-modified DNA was used for the Illumina GoldenGate Methylation assay (Illumina, San Diego, CA). As described previously, methylation status of 1505 CpG sites selected from more than 800 genes were investigated using the GoldenGate Methylation Cancer Panel I (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.10 The panel includes tumor suppressor genes, oncogenes, genes involved in DNA repair, cell cycle control, cell differentiation, and apoptosis. Image processing and intensity data extraction were performed with Illumina-supplied equipment. Each methylation data point is represented by fluorescent signals from the unmethylated (U) and methylated (M) alleles. Methylation status of the interrogated CpG site is calculated as the ratio of fluorescent signal from one allele relative to the sum of both methylated and unmethylated alleles (β value).

The β value provides a continuous measurement of levels of DNA methylation at a CpG site, ranging from 0 (completely unmethylated) to 1 (completely methylated). Differential methylation was computed between H&E-stained tumor samples and immunohistochemically stained tumor samples. Differential methylation was defined as follows: (1) a mean methylation level difference (delta β) of at least 0.17 (Δβ ≥ 0.17), and (2) a P value of <.05 as determined by Student t test (two-tailed, unequal variance). A Δβ value of at least 0.17 was chosen as this represents the most stringent criterion applied in previous studies.10

Results

Membrane Slide Preparation

Without pretreatment of membrane slides, we found that tissue sections lost adhesion to the membranes and were washed off in all cases (10/10) during AR. We could solve this problem by three modification steps. First, membrane slides were UV-treated to make them more hydrophilic, and therefore the tissue sections adhered better (PALM Microlaser Systems, Los Angeles, CA). To further improve tissue adhesion to the membrane, membranes were coated with undiluted poly-l-lysine 0.1%, a positively charged amino acid polymer. After drying of the coated slides in a slide holder in vertical position for 1 hour at room temperature, tissue sections were mounted on the UV and poly-l-lysine pretreated membrane slides. Additional incubation at 60°C for 2 hours after tissue mounting resulted in enhanced adhesion.

Antigen Retrieval

Standard AR with HIER at high temperature (90°C) may affect tissue morphology on membrane slides as well as membrane integrity. Therefore, reduction of the AR temperature helps to minimize these risks. In our study we compared two different methods of AR: AR with pepsin at 37°C and AR with HIER at low temperature (60°C). For both methods of AR, all of the tissue sections (10/10) maintained adhesion to the membrane. In our hands, AR with pepsin showed the best results when the preheated pepsin solution was directly pipetted onto the horizontally placed slide. The optimum AR could be performed at 37°C for 10 minutes. Longer incubation times (15 and 20 minutes) led to partial digestion and destruction of the tissue section. The alternative method that does not bear the risk of tissue digestion is HIER. AR with HIER was performed at low temperature (60°C) to protect the tissue and membrane integrity. Occasionally, we observed bleb formation underneath the membrane that developed during the HIER procedure. However, these blebs did not affect the quality of the subsequent IHC, and they disappeared when we let the slides dry at room temperature before LAM. In addition, we examined two retrieval solutions for subsequent CD20 and CD30 staining: Dako Target Retrieval Solution and DakoCytomation Target Retrieval Solution, pH 9. The quality of the staining for CD20 was comparable with either retrieval solution in all five cases. In contrast, CD30 detection showed a better staining result when using Dako Target Retrieval Solution (5/5). We also studied different incubation times of AR, and 16 hours was optimal for CD20. Staining quality did not improve by the use of longer incubation times (24, 42, or 48 hours). Interestingly, the best staining results for CD30 were obtained after 42 hours of incubation time. Whereas 48 hours of incubation did not improve the results achieved with 42 hours, shorter incubation times resulted in poorer quality staining.

Immunohistochemistry

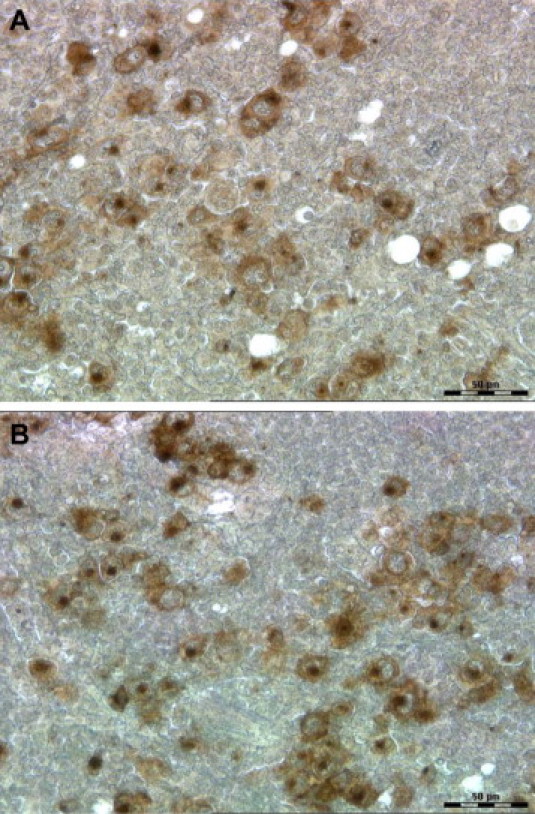

As primary antibody for CD20 we used monoclonal mouse anti-human CD20cy clone L26 (Dako), and for CD30 we used a monoclonal mouse anti-human CD30 clone Ber-H2 (Dako). Different dilutions and incubation times were tested for both antibodies. The anti-CD20 antibody showed specific staining with unremarkable background staining using any of the tested dilutions (1:400 up to 1:200) with an optimum incubation time of 30 minutes in all five cases of PMLBCL. Best staining results for CD30 were observed with a dilution of 1:50 and an incubation time of 30 minutes in all five cases of CHLNS. The secondary antibody, labeled polymer-HRP anti-mouse, was applied for 30 minutes at room temperature in all cases. Incubation time of DAB+ substrate buffer and DAB+ chromogen was 10 minutes for CD30. Because of a strong and prompt reaction for the CD20 staining we reduced the incubation time of DAB+ substrate buffer and DAB+ chromogen to 5 minutes (Figure 1). We studied five individual cases of each lymphoma, PMLBCL, and CHLNS and by using the described protocol for IHC on PEN membrane slides we obtained highly consistent staining results for CD20 (5/5 cases of PMLBCL) and CD30 (5/5 cases of CHLNS). The quality of IHC on PEN membrane slides was comparable with the quality on glass slides (Figure 2, A and B).

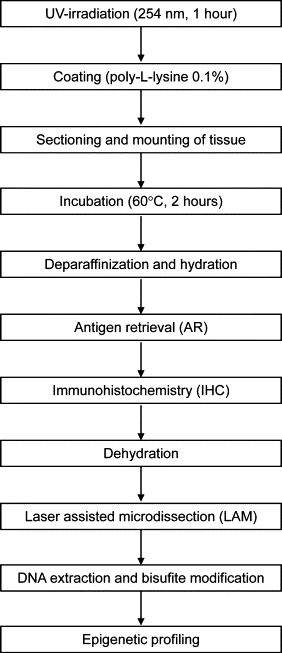

Figure 1.

Technical steps for immunohistochemistry of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections on membrane slides for subsequent laser-assisted microdissection and DNA methylation profiling.

Figure 2.

CD30 staining of Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells in a Hodgkin's lymphoma on a regular glass slide (A) and on a polyethylene naphthalate membrane slide (B). Both sections of the FFPE sample, either on glass slide or membrane slide, are shown without hematoxylin counterstaining and without cover slide; original magnification, ×40.

Microdissection and Automatic Cell Recognition

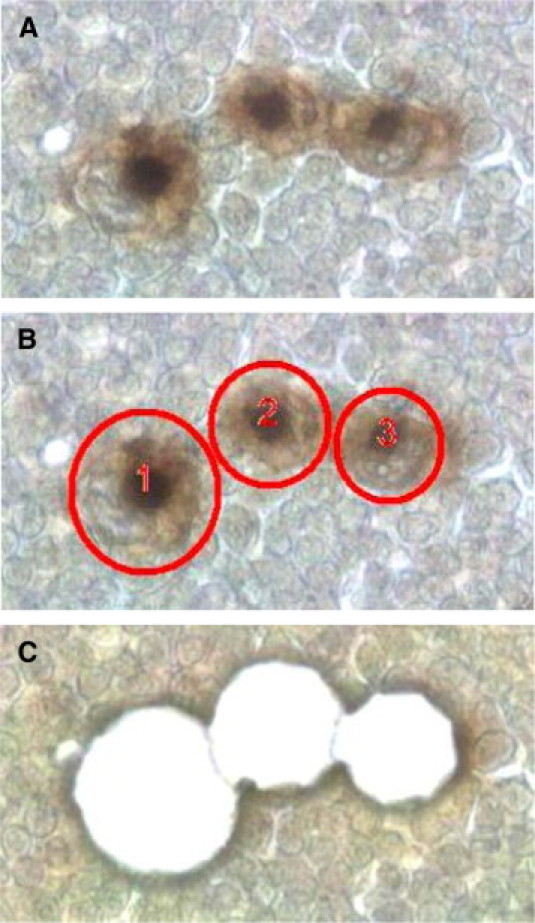

For our study, microdissection of tumor cells was performed using the Leica LMD 6000 (Figure 3, A–C). In addition, we evaluated the mode of operation of three leading microdissecting systems: Arcturus XT, Leica LMD 6000, and PALM MicroBeam (Table 1). A common feature of all systems is an UV laser for cutting cells from tissue sections. Whereas the Arcturus XT contains an additional IR laser for cell capturing, the other systems do not include an IR laser. Instead cells are collected in a tube by gravity (Leica LMD 6000) or by UV laser–based catapultation (PALM MicroBeam). In our hands, all systems were able to microdissect the target cells when manually operated. The major difference between the three systems arose in the collection step. The microdissected cells could be quickly collected in the systems without IR laser (Leica LMD 6000 and PALM MicroBeam), whereas the Arcturus XT required a careful set up of the IR laser parameters, especially when collecting single cells. Also, we tested the automatic cell recognition programs of two systems, Arcturus XT (AutoScanXT Software Module) and Leica LMD 6000 (AutoVision Control). AutoScan efficiently detected our immunohistochemically stained cells of interest, whereas the AutoVision Control installed in the Leica LMD 6000 seems to be better suited for immunofluorescence than for IHC with DAB because the system requires a high contrast between the cells of interest and the background.

Figure 3.

CD30+ Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells in a Hodgkin's lymphoma before microdissection (A), selected for microdissection (B), and after microdissection (C) using the Leica LMD 6000; original magnification, ×63.

Table 1.

Comparison of Laser-Assisted Microdissection Systems

| Arcturus XT | Leica LMD 6000 | PALM MicroBeam | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Company | MDS Analytical Technologies | Leica Microsystems | Carl Zeiss |

| Infrared (IR) laser | Yes | No | No |

| Ultraviolet (UV) laser | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Collection of microdissected cells | Cells captured with IR laser | Cells fall by gravity into a tube | Cells catapulted with UV laser in a tube |

| Automatic cell recognition program | Available and tested | Available and tested | Available, not tested |

| Shape expansion modus* | No | Yes | Yes |

Shape expansion modus: software feature that allows increasing the perimeter of the cutting line of the automatically selected cells to avoid cell damage during the cutting procedure.

DNA Quantity, DNA Quality, and DNA Methylation

We compared the quantity of DNA extracted with LAM from approximately 75,000 H&E-stained tumor cells and also with ILAM from approximately 75,000 immunohistochemically stained tumor cells for each of the five cases of PMLBCL. The amount of DNA recovered from immunohistochemically stained tissue was lower in all cases and varied from 64% to 9% compared with H&E-stained tissue (Table 2).

Table 2.

DNA Recovery from H&E or Immunohistochemically Stained Tumor Cells after Microdissection of Five Cases of PMLBCL

| Case no. | DNA recovery after H&E and LAM (ng/75000 cells) | DNA recovery after IHC and ILAM (ng/75000 cells) | DNA recovery after IHC compared with H&E |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 96 | 46 | 48% |

| 2 | 210 | 135 | 64% |

| 3 | 378 | 50 | 13% |

| 4 | 483 | 45 | 9% |

| 5 | 202 | 82 | 41% |

DNA amount refers to approximately 75,000 microdissected tumor cells per case.

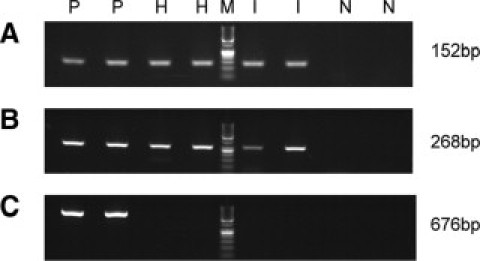

Although DNA quantity was different in H&E compared with immunohistochemically stained tumor cells, DNA quality was identical using both staining methods. DNA quality was assessed by PCR for the β-globin gene using three different sets of primers that produce amplicons of increasing size.9 DNA was extracted from immunohistochemically stained tumor cells and compared with DNA isolated from H&E-stained tumor cells of the same sample. Gel electropheresis of the amplified products showed similar levels of the 152-bp and 268-bp amplicons for both staining procedures. The 676-bp product was not detectable in either preparation (Figure 4, A–C).

Figure 4.

PCR products after PCR amplification of the β-globin gene using three different sets of primers. A: Detection of 152-bp amplicon. B: Detection of 268-bp amplicon. C: Detection of 676-bp amplicon. P indicates positive control; H, PCR of microdissected tumor cells stained with H&E; M, molecular weight marker; I, PCR of microdissected tumor cells stained with immunohistochemistry; N, negative control. PCR of controls, H, and I were performed as duplicates.

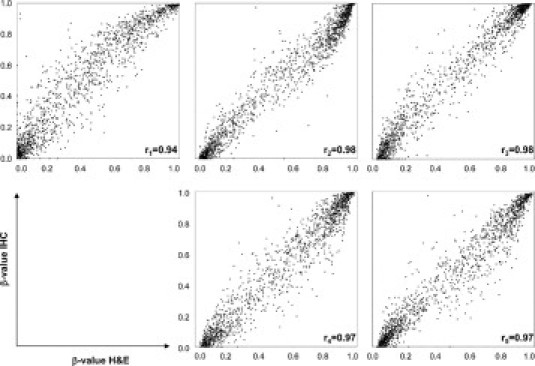

To evaluate our IHC staining method for epigenetic analysis we analyzed methylated CpG targets using the Illumina GoldenGate Methylation array for five different cases of PMLBCL. DNA of tumor cells isolated from immunohistochemically stained tissue or H&E-stained tissue of the same sample was isolated and bisulfate modified. Analysis of target CpG methylation revealed a very strong correlation when plotting the data of DNA isolated from H&E-stained tumor cells and immunohistochemically stained tumor cells with a minimum of r = 0.94 and a maximum of r = 0.98 (Figure 5). Furthermore, we calculated differential methylation between H&E-stained cases of PMLBCL and immunohistochemically stained cases of PMLBCL. Of the 1505 investigated CpG targets, 1501 CpGs (99,7%) revealed no differential methylation status. Significant differential methylation as defined by a Δβ value of at least 0.17 was only observed in four CpG targets (P < 0.05; Table 3).

Figure 5.

Illumina GoldenGate Methylation array of five individual cases. Each plot shows the correlation of target CpG methylation of DNA isolated from H&E-stained tumor cells (x axis) compared with DNA isolated from immunohistochemically stained tumor cells (y axis). A minimum correlation of r = 0.94 and a maximum correlation of r = 0.98 was observed.

Table 3.

CpG Targets with Differential Methylation (Δβ ≥0.17) between H&E or Immunohistochemically Stained Tumor Cells

| Target ID* | β (HE) | β (IHC) | Δβ | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p16_seq_47_S85_F | 0.509 | 0.833 | 0.324 | 0.002 |

| EGR4_E70_F | 0.343 | 0.633 | 0.290 | 0.000 |

| NRG1_E74_F | 0.646 | 0.455 | 0.191 | 0.044 |

| VAMP8_E7_F | 0.239 | 0.411 | 0.172 | 0.015 |

Gene symbols are contained within the Target ID before the first underscore. β (HE) indicates mean beta value of all five cases of PMLBCL stained with H&E; β (IHC), mean beta value of all five cases of PMLBCL stained with IHC (CD20); Δβ, differential methylation between β (HE) and β (IHC). P value calculation: see Materials and Methods.

Discussion

LAM represents a powerful tool for molecular analysis of specific cell populations from tissue specimens. The original prototype, invented in 1996, is based on an IR laser that captures target cells mounted on a glass slide onto a thermal sensitive polymer.5 Since the invention of IR-based laser capture microdissection, several changes have been introduced to the original concept. Today, all LAM systems such as the Arcturus XT, Leica LMD 6000, and PALM MicroBeam are based on an UV laser that cuts the specific cells of interest from a tissue section attached to an underlying membrane. For many studies, routine H&E staining is sufficient to identify the cells of interest for LAM. However, when morphological cell characteristics obtained by routine H&E staining do not allow adequate recognition of the target cells, IHC is required and this approach has been successfully applied to frozen tissue samples as well as to ethanol fixed tissue.11,12,13,14 IHC protocols for frozen as well as ethanol-fixed sections mounted on PEN membrane slides do not represent a technical challenge because both preservation methods do not require AR before IHC. In contrast, the use of IHC on FFPE tissue sections for cutting LAM is an important technical challenge because FFPE tissue samples often require AR and the procedure is complicated on PEN membrane slides. Two major technical challenges have to be overcome for AR in FFPE specimens on membrane slides. (1) The adhesion properties of the PEN membrane to the tissue sections have to be improved because the tissue often washes off the membrane during AR. (2) Common methods of AR for FFPE specimens at 90°C are not suitable for FFPE tissue sections on PEN membranes. More importantly, it was unclear whether AR and IHC affect DNA integrity and DNA methylation.

Because no data existed in the literature about AR and IHC for ILAM and epigenetic analysis, the goal of the present study was to establish an optimized protocol compatible with both ILAM and DNA methylation profiling. We describe an optimized protocol for membrane and tissue preparation as well as different methods of AR for a subsequent immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1). Following this protocol we obtained highly reproducible staining results with IHC on PEN membrane slides for two antibodies, CD20 in PMLBCL and CD30 in CHLNS, and the quality of staining using PEN membrane slides was comparable with the quality of staining using glass slides (Figure 2). Our IHC protocol using a chromogenic substrate can be applied to many mitochondrial or genomic DNA based studies such as those aimed at discovery of mechanisms of gene regulation related to carcinogenesis and human disease.15,16,17 This new protocol likely may also be applicable to miRNA analysis, because FFPE samples allow the extraction and analysis of miRNA18,19,20; however, further technical studies are needed to confirm that this application is possible.

Microdissection of tumor cells for subsequent studies of DNA quantity, DNA quality, and DNA methylation was performed using the Leica LMD 6000 (Figure 3). For this technical study, we microdissected tumor cells without using any automatic cell recognition program. However, in studies where it is necessary to microdissect many cells, cell recognition programs that automatically detect positively immunostained target cells can be helpful and time-efficient. This is especially true if the target cells do not grow in clusters but are arranged as scattered single cells, for example the Hodgkin-Reed-Sternberg cells in Hodgkin's lymphoma, melanocytes in the skin, or certain types of neurons such as Purkinje cells. For these purposes we evaluated the available cell recognition programs of two systems, AutoScan (Arcturus XT) and AutoVision Control (Leica LMD 6000; Table 1). AutoScan accurately distinguished our immunohistochemically stained cells from the background while the AutoVision Control of the Leica LMD 6000 seems to work better with a higher contrast between the cells of interest and the background (e.g., immunofluorescence-based cell labeling). An additional important feature for collecting automatically detected cells is an integrated shape expansion modus of the cutting line. This feature is extremely useful to avoid cell damage during the cutting procedure of the automatically detected cells of interest, especially when single cells have to be isolated (Table 1).

DNA extraction of approximately 75,000 tumor cells of the same case showed that the amount of DNA recovered from immunohistochemically stained tissue was lower than the DNA amount recovered from H&E stained tissue. DNA recovery from immunohistochemically stained tissue varied from 64% to 9% compared with H&E-stained tissue (Table 2). We hypothesize that DAB used for IHC interferes with the isolation and recovery of DNA from tissue sections; however, further research is needed to explore the exact mechanism involved. A similar decrease to that seen for recoverable DNA in the present study was shown for recoverable mRNA.21

Although the amount of DNA in immunohistochemically stained tissue compared with H&E-stained tissue is lower, the quality of the isolated DNA was similar based on PCR analysis of the β-globin gene and methylated CpG target analysis using the Illumina GoldenGate Methylation array. β-globin PCR showed identical results for H&E-stained tumor cells and immunohistochemically stained tumor cells as both short- and medium-sized fragments were detected by both staining methods (Figure 4). The inability to amplify the larger fragment (676 bp) is consistent with previous reports, demonstrating that amplification of large-size sequences is difficult because of the fixation and embedding processes that lead to DNA fragmentation.9

DNA quality was further evaluated by epigenetic profiling of DNA isolated from H&E-stained tumor cells or immunohistochemically stained tumor cells of five individual cases of PMLBCL. Illumina GoldenGate analysis showed an excellent correlation when plotting the data of DNA isolated from H&E-stained tumor cells and immunohistochemically stained tumor cells with a minimum of r = 0.94 and a maximum of r = 0.98. The minimal difference observed is most likely attributable to the technical reproducibility of LAM but not to IHC (Figure 5). In addition, differential methylation was computed between H&E-stained tumor samples and immunohistochemically stained tumor samples (Table 3). For differential methylation calculation, a Δβ value of at least 0.17 or more was chosen as this represents the most stringent criterion applied in previous studies, which used the Illumina GoldenGate Methylation array.10,22 Applying this criterion, 1501 of the 1505 investigated CpG targets (99.7%) revealed no differential methylation status. Only four CpG sites of the investigated 1505 CpG sites were differentially methylated when comparing H&E to IHC (P < 0.05). In more recent studies, a Δβ value of 0.30 or even 0.34 is chosen for computation of differential methylation between different groups.23,24 Applying these criteria, our data reveal only one Δβ ≥ 0.30 and no differentially methylated target for Δβ ≥ 0.34, respectively (P < 0.05). These data confirm that our protocol for AR and IHC did not affect the DNA quality and the DNA methylation profile of tumor cells isolated by ILAM. In summary, the protocol described in this report opens a wide range of applications for large-scale genomic and epigenetic analysis of microdissected cells using archival IHC-stained FFPE tissue sections.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the intramural program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

This work was prepared as part of our official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that “Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.” Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a U.S. Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person's official duties.

M.R.E.-B. is an inventor on all NIH patents covering laser-capture microdissection technology and receives royalty payments through the NIH technology transfer program.

References

- 1.Holliday R. The inheritance of epigenetic defects. Science. 1987;238:163–170. doi: 10.1126/science.3310230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esteller M. Epigenetics in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1148–1159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feinberg AP, Vogelstein B. Hypomethylation distinguishes genes of some human cancers from their normal counterparts. Nature. 1983;301:89–92. doi: 10.1038/301089a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greger V, Passarge E, Hopping W, Messmer E, Horsthemke B. Epigenetic changes may contribute to the formation and spontaneous regression of retinoblastoma. Hum Genet. 1989;83:155–158. doi: 10.1007/BF00286709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emmert-Buck MR, Bonner RF, Smith PD, Chuaqui RF, Zhuang Z, Goldstein SR, Weiss RA, Liotta LA. Laser capture microdissection. Science. 1996;274:998–1001. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosai J. Why microscopy will remain a cornerstone of surgical pathology. Lab Invest. 2007;87:403–408. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niyaz Y, Stich M, Sagmuller B, Burgemeister R, Friedemann G, Sauer U, Gangnus R, Schutze K. Noncontact laser microdissection and pressure catapulting: sample preparation for genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analysis. Methods Mol Med. 2005;114:1–24. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-923-0:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gjerdrum LM, Lielpetere I, Rasmussen LM, Bendix K, Hamilton-Dutoit S. Laser-assisted microdissection of membrane-mounted paraffin sections for polymerase chain reaction analysis: identification of cell populations using immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization. J Mol Diagn. 2001;3:105–110. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60659-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillio-Tos A, De Marco L, Fiano V, Garcia-Bragado F, Dikshit R, Boffetta P, Merletti F. Efficient DNA extraction from 25-year-old paraffin-embedded tissues: study of 365 samples. Pathology. 2007;39:345–348. doi: 10.1080/00313020701329757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bibikova M, Lin Z, Zhou L, Chudin E, Wickham Garcia E, Wu B, Doucet D, Thomas NJ, Wang Y, Vollmer E, Goldmann T, Seifart C, Jiang W, Barker DL, Chee MS, Floros J, Fan JB. High throughput DNA methylation profiling using universal bead arrays. Genome Res. 2006;16:383–393. doi: 10.1101/gr.4410706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fend F, Emmert-Buck MR, Chuaqui R, Cole K, Lee J, Liotta LA, Raffeld M. Immuno-LCM: laser capture microdissection of immunostained frozen sections for mRNA analysis. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:61–66. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65251-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buckanovich RJ, Sasaroli D, O'Brien-Jenkins A, Botbyl J, Conejo-Garcia JR, Benencia F, Liotta LA, Gimotty PA, Coukos G. Use of immuno-LCM to identify the in situ expression profile of cellular constituents of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:635–642. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.6.2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez-Canales J, Hanson JC, Tangrea MA, Erickson HS, Albert PS, Wallis BS, Richardson AM, Pinto PA, Linehan WM, Gillespie JW, Merino MJ, Libutti SK, Woodson KG, Emmert-Buck MR, Chuaqui RF. Identification of a unique epigenetic sub-microenvironment in prostate cancer. J Pathol. 2007;211:410–419. doi: 10.1002/path.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartmann S, Martin-Subero JI, Gesk S, Husken J, Giefing M, Nagel I, Riemke J, Chott A, Klapper W, Parrens M, Merlio JP, Kuppers R, Brauninger A, Siebert R, Hansmann ML. Detection of genomic imbalances in microdissected Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells of classical Hodgkin's lymphoma by array-based comparative genomic hybridization. Haematologica. 2008;93:1318–1326. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Killian JK, Bilke S, Davis S, Walker RL, Killian MS, Jaeger EB, Chen Y, Hipp J, Pittaluga S, Raffeld M, Cornelison R, Smith WI, Jr, Bibikova M, Fan JB, Emmert-Buck MR, Jaffe ES, Meltzer PS. Large-scale profiling of archival lymph nodes reveals pervasive remodeling of the follicular lymphoma methylome. Cancer Res. 2009;69:758–764. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baloglu G, Haholu A, Kucukodaci Z, Yilmaz I, Yildirim S, Baloglu H. The effects of tissue fixation alternatives on DNA content: a study on normal colon tissue. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2008;16:485–492. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e31815dffa6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srinivasan M, Sedmak D, Jewell S. Effect of fixatives and tissue processing on the content and integrity of nucleic acids. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1961–1971. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64472-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siebolts U, Varnholt H, Drebber U, Dienes HP, Wickenhauser C, Odenthal M. Tissues from routine pathology archives are suitable for microRNA analyses by quantitative PCR. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:84–88. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.058339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szafranska AE, Davison TS, Shingara J, Doleshal M, Riggenbach JA, Morrison CD, Jewell S, Labourier E. Accurate molecular characterization of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues by microRNA expression profiling. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:415–423. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.080018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doleshal M, Magotra AA, Choudhury B, Cannon BD, Labourier E, Szafranska AE. Evaluation and validation of total RNA extraction methods for microRNA expression analyses in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. J Mol Diagn. 2008;10:203–211. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2008.070153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gjerdrum LM, Abrahamsen HN, Villegas B, Sorensen BS, Schmidt H, Hamilton-Dutoit The influence of immunohistochemistry on mRNA recovery from microdissected frozen and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2004;13:224–233. doi: 10.1097/01.pdm.0000134779.45353.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ladd-Acosta C, Pevsner J, Sabunciyan S, Yolken RH, Webster MJ, Dinkins T, Callinan PA, Fan JB, Potash JB, Feinberg AP. DNA methylation signatures within the human brain. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1304–1315. doi: 10.1086/524110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin-Subero JI, Ammerpohl O, Bibikova M, Wickham-Garcia E, Agirre X, Alvarez S, Brueggemann M, Bug S, Calasanz MJ, Deckert M, Dreyling M, Du MQ, Duerig J, Dyer MJ, Fan JB, Gesk S, Hansmann ML, Harder L, Hartmann S, Klapper W, Kueppers R, Montesinos-Rongen M, Nagel I, Pott C, Richter J, Roman-Gomez J, Seifert M, Stein H, Suela J, Truemper L, Vater I, Prosper F, Haferlach C, Cruz Cigudosa J, Siebert R. A comprehensive microarray-based DNA methylation study of 367 hematological neoplasms. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6986. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Riain C, O'Shea DM, Yang Y, Le Dieu R, Gribben JG, Summers K, Yeboah-Afari J, Bhaw-Rosun L, Fleischmann C, Mein CA, Crook T, Smith P, Kelly G, Rosenwald A, Ott G, Campo E, Rimsza LM, Smeland EB, Chan WC, Johnson N, Gascoyne RD, Reimer S, Braziel RM, Wright GW, Staudt LM, Lister TA, Fitzgibbon J. Array-based DNA methylation profiling in follicular lymphoma. Leukemia. 2009;23:1858–1866. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]