Abstract

The NK1.1 molecule participates in NK, NKT, and T-cell activation, contributing to IFN-γ production and cytotoxicity. To characterize the early immune response to Plasmodium chabaudi AS, spleen NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells were compared in acutely infected C57BL/6 mice. The first parasitemia peak in C57BL/6 mice correlated with increase in CD4+NK1.1+TCR-αβ+, CD8+NK1.1+TCR-αβ+, and CD4+NK1.1−TCR-αβ+ cell numbers per spleen, where a higher increment was observed for NK1.1+ T cells compared to NK1.1− T cells. According to the ability to recognize the CD1d-α-GalCer tetramer, CD4+NK1.1+ cells in 7-day infected mice were not predominantly invariant NKT cells. At that time, nearly all NK1.1+ T cells and around 30% of NK1.1− T cells showed an experienced/activated (CD44HICD69HICD122HI) cell phenotype, with high expression of Fas and PD-L1 correlating with their low proliferative capacity. Moreover, whereas IFN-γ production by CD4+NK1.1+ cells peaked at day 4 p.i., the IFN-γ response of CD4+NK1.1− cells continued to increase at day 5 of infection. We also observed, at day 7 p.i., 2-fold higher percentages of perforin+ cells in CD8+NK1.1+ cells compared to CD8+NK1.1− cells. These results indicate that spleen NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells respond to acute P. chabaudi malaria with different kinetics in terms of activation, proliferation, and IFN-γ production.

Introduction

The asexual blood-stage of the Plasmodium spp. is responsible for the pathology and morbidity caused by malaria, an infectious disease that remains the most devastating illness afflicting tropical countries. There are an estimated 350 to 500 million clinical malaria cases every year resulting in >1 million deaths, mostly children under 5 years of age (WHO 2007). The immune response to malaria involves the orchestration of a complex network of innate and adaptive immune cells that can result in both protection and disease. This complexity is exemplified by the fact that proinflammatory cytokines required for parasite control are also involved in malaria syndromes, such as cerebral malaria and anemia (Schofield and Grau 2005; Clark and others 2006). However, the immunological mechanisms responsible for these different outcomes are not yet fully understood, and the relative contribution of T-cell subpopulations remains unclear.

The acute phase of blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi malaria, a suitable model for the human disease caused by Plasmodium falciparum (Cox and others 1987), is accompanied by intense lymphocyte activation with strong proliferation of splenic T and B cells and production of type 1 effector molecules, such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and IgG2a (Falanga and others 1987; Langhorne and others 1989; D'Imperio Lima and others 1996). The involvement of this response in mice resistance is suggested by the fact that IFN-γ (Stevenson and others 1990) and acute-phase antibodies (Mota and others 1998) have been implicated in the initial control of parasitemia. Moreover, parasite-reactive B cells are included among those cells polyclonally activated during acute infection (Lima and others 1991). The swiftness and magnitude of lymphocyte responses to P. chabaudi infection indicate the participation of cells from the innate immune system.

CD161 molecules comprise a family of C-type lectin receptors that includes NKRP1C (also known as CD161c), which is recognized by NK1.1 antibodies in C57BL/6 and C57BL/10 mouse strains (Huntington and others 2007). CD161/NK1.1 molecule associates with the ITAM-containing FcɛRIγ adapter and its cross-linking with anti-NK1.1 mAb induces NK-cell-mediated cytotoxicity and cytokine production (Arase and others 1996, 1997). NK1.1 molecule is expressed by all NK cells of C57BL/6 mice and in a heterogeneous subset of T cells (including CD4−CD8−, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells) commonly referred to as NKT cells, some of which recognize CD1d antigens (Bendelac and others 1995; Godfrey and others 2000). Thus, although NK1.1 expression is a feature of CD1d-restricted NKT cells, a proportion of NK1.1+ T cells are restricted by MHC I and II molecules (Godfrey and others 2004). Moreover, after activation, NK1.1 expression can be suppressed in CD1d-restricted NKT cells (Chen and others 1997) and induced in conventional T cells (Slifka and others 2000). Among the CD1d-restricted NKT cells, the invariant NKT (iNKT) cells can be specifically activated by CD1d tetramers loaded with α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer), a specific but artificial ligand for these cells (Kawano and others 1997). A considerable fraction of CD1d-restricted NKT cells uses the invariant Vα14Jα18 TCR-α chain, which is preferentially associated with TCR-β chains coded by Vβ8, Vβ7, and Vβ2 gene segments (Godfrey and others 2004).

Because a considerable proportion of spleen T cells express the NK1.1 molecule during the acute phase of P. chabaudi malaria, we set out to compare the relative contribution of NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells to the intense T-cell response against this parasite. CD1d-unrestricted NK1.1+ T cells have been shown to play a protective role against liver stages of Plasmodium yoelii (Pied and others 2000). In addition, CD1d-restricted NK1.1+ T cells contribute to the early immune response induced by Plasmodium berghei (Schmieg and others 2003) and P. yoelii (Mannoor and others 2001; Soulard and others 2007). Thus, characterizing spleen NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells during the early stages of P. chabaudi infection could help toward understanding the role of lymphocyte subpopulations in malaria, elucidating the cellular and molecular pathways underlying the development of both protective and pathogenic immune responses.

Materials and Methods

Mice, parasites, and infection

Six- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 (originally from The Jackson Laboratory) male mice were bred under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Isogenic Mice Facility (Department of Immunology/University of São Paulo, Brazil). P. chabaudi AS was maintained as described elsewhere (Stevenson and others 1990). Mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 106 infected red blood cells (iRBC). Parasitemias were monitored by microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained thin tail blood smears.

Spleen cell suspension

Spleen cells were washed and maintained in cold RPMI 1640, supplemented with penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 μg/mL), 2-mercaptoethanol (50 μM), l-glutamine (2 mM), sodium pyruvate (1 mM), and 3% heat-inactivated FCS. All supplements were purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies. The numbers of cells per spleen were counted using a Neubauer chamber (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Phenotypic analysis of spleen cells

Spleen cells (106) were stained with APC-, PercP-, FITC-, PE-, or CyChrome (Cy)-labeled mAbs to CD4 (H129.19), CD8 (53-6.7), CD161/NK1.1 (PK 136), TCR-β chain (H57-597), CD44 (KM-201), CD69 (H1.2F3), CD122 (IL-2R chain β, TM-β1), Fas/CD95 (Jo2), Fas-L/CD95L (MFL3), PD-1/CD279 (J43), PD-L1/CD274 (B7-H1/MIH1), TCR-Vβ7 (TR310), TCR-Vβ8 (F23.1) from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA) and with PE-labeled CD1d-α-GalCer tetramer (La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology, La Jolla, CA; NIH). Stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur device with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

IFN-γ and perforin intracellular detection

Concerning IFN-γ and perforin intracellular detection, spleen cells (106) were cultured with GolgiStop, according to the manufacturer's instructions, in the presence of 5 μg/mL plate-bound anti-CD3 mAb (145-2C11) or medium alone, for 10 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After washing, cells were surface-stained with FITC- and APC-labeled mAb to CD4 and CD8. Cells were then fixed with Cytofix/Cytoperm buffer and stained with APC- and PE-labeled mAb to IFN-γ (XMG-1.2) and perforin, diluted in Perm/Wash buffer, and analyzed by flow cytometry. All reagents were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA).

CFSE proliferation assay

T-cell proliferation was measured as described elsewhere (Elias and others 2005). In brief, spleen cells (3 × 107) were incubated with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), at a final concentration of 5 μM, diluted in PBS with 0.1% BSA, for 30 min at 37°C. Cells (106) were then cultured in 96-well plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) with 5 μg/mL plate-bound anti-CD3 mAb or medium alone, for 72 h, at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After incubation, cells were stained with PE-, PercP-, and APC-labeled mAb to NK1.1, CD4, and CD8 from BD Pharmingen and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Mann–Whitney U-test. The IFN-γ kinetics was compared with Tukey's multiple comparison tests. GraphPad Prism 4 software was used, where differences between groups were considered significant when P < 0.05 (5%).

Results

P. chabaudi parasitemia peak correlates with high numbers of NK1.1+TCR-αβ+ and NK1.1−TCR-αβ+ cells per spleen

To evaluate the kinetics of NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T-cell populations in P. chabaudi malaria, C57BL/6 mice were infected with 106 iRBC. According to parasitemia curves, C57BL/6 mice developed a first peak at day 7 p.i. and recrudescent second peak at day 17 p.i. (Fig. 1A). The numbers of CD4+NK1.1+TCR-αβ+, CD8+NK1.1+TCR-αβ+, and CD4+NK1.1−TCR-αβ+ cells per spleen progressively rose until day 7 p.i., with a higher increase for NK1.1+ T cells compared to NK1.1− T cells (Fig. 1B). The differences in CD4−CD8− T-cell subpopulations were not statistically significant. Among NK1.1+ T cells from 7-day infected mice, CD4+, CD8+, and CD4−CD8− cells represented 63%, 33%, and 4%, respectively. On the other hand, at day 7 p.i., 19% of CD4+, 13% of CD8+, and 75% of CD4−CD8− T cells expressed NK1.1 molecules. This analysis showed that CD4+NK1.1+TCR-αβ+ and CD8+NK1.1+TCR-αβ+ T-cell populations are largely increased in the spleen during the acute P. chabaudi malaria, even though CD4+NK1.1−TCR-αβ+ cells still represent the major T-cell population at the early infection.

FIG. 1.

Parasitemias and numbers of spleen NK1.1+TCR-αβ+ and NK1.1−TCR-αβ+ T cells in P. chabaudi-infected C57BL/6 mice. (A) Parasitemia curves in C57BL/6 mice infected with 106 infected red blood cell (iRBC). Each curve corresponds to the means ± SD (n = 10). *P < 0.05, infected mice compared with noninfected mice. (B) Numbers per spleen of CD4+TCR-αβ+, CD8+TCR-αβ+, and CD4−CD8−TCR-αβ+ (DN, double negative) cells expressing NK1.1 molecule in C57BL/6 mice at days 4 and 7 p.i. with 106 iRBC. Noninfected mice were used as controls. Data represent the means ± SD (n = 8). *P < 0.05, infected mice compared with noninfected mice. Data are representative of 3 repeat experiments.

Spleen NK1.1+TCR-αβ+ cells from P. chabaudi-infected mice are not predominantly iNKT cells

To verify if iNKT cells were included among the NK1.1+ T-cell population generated during acute P. chabaudi malaria, spleen cells recognizing CD1d-α-GalCer tetramer and expressing TCR-Vβ7 and TCR-Vβ8 chains were analyzed in noninfected mice (controls) and in 7-day infected C57BL/6 mice. In control mice, the majority of CD4+NK1.1+TCR-αβ+ and CD4−CD8−NK1.1+TCR-αβ+ cells were positive for CD1d-α-GalCer tetramer, while CD8+NK1.1+TCR-αβ+ cells were negative (Fig. 2A). At day 7 p.i., a sharp increase in percentages of NK1.1+ cells that were negative for CD1d-α-GalCer tetramer was observed in all T-cell subpopulations, whereas frequencies of CD1d-α-GalCer tetramer+ cells were consistently reduced. For the NK1.1−TCR-αβ+ cell subpopulation, only a small fraction of cells was positive for CD1d-α-GalCer tetramer in control and 7-day infected mice. As expected, higher percentages of Vβ8+ and Vβ7+ cells were observed in CD4+NK1.1+ cells compared to CD4+NK1.1− cells. However, a decrease in Vβ8+ cell frequencies within the CD4+NK1.1+ and CD4+NK1.1− cells occurred after infection, whereas Vβ7+ cell frequencies remained unchanged (Fig. 2B). To evaluate the possibility that upon activation iNKT cells have down-regulated the expression of their invariant TCR, we compared the expression of TCR-β chain in CD4+NK1.1+ and CD4+NK1.1− cells. The data presented in Figure 2C show that TCR-β levels in CD4+NK1.1+ cells from 7-day infected mice were even higher than those levels found in CD4+NK1.1− cells from both groups of mice. Moreover, the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of these CD4+NK1.1+ cells were 2-fold increased compared to their counterparts in noninfected mice. Taken together, these results suggested that the majority of spleen NK1.1+TCR-αβ+ cells generated in acutely P. chabaudi-infected mice were not iNKT cells.

FIG. 2.

Recognition of CD1d-α-GalCer tetramer and expression of TCR-Vβ7 and TCR-Vβ8 chains by spleen NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells from P. chabaudi-infected C57BL/6 mice. (A) Dot plots showing gated CD4+TCR-αβ+, CD8+TCR-αβ+, and CD4−CD8−TCR-αβ+ (DN, double negative) cells that recognize α-GalCer tetramer and express NK1.1 molecule at day 7 p.i. with 106 infected red blood cells (iRBCs). Noninfected mice were used as controls. Numbers in dot plots represent the means ± SD (n = 4–6) of the percentages of each subpopulation. *P < 0.05, infected mouse cells compared with noninfected mouse cells. (B) Dot plots showing gated CD4+NK1.1+TCR-αβ+ and CD4+NK1.1−TCR-αβ+ cells that use the TCR-Vβ7 and TCR-Vβ8 chains at day 7 p.i. with 106 iRBC. Noninfected mice were used as controls. Numbers in dot plots represent the means ± SD (n = 6–8) of the percentages of positive cells. *P < 0.05, infected mouse cells compared with noninfected mouse cells; **P < 0.05, NK1.1+ cells compared with NK1.1− cells. (C) Histograms showing TCR-β expression in CD4+NK1.1+ and CD4+NK1.1− cells from the same groups of mice. Numbers in histograms represent the means ± SD (n = 6–8) of mean fluorescence intensity in gated CD4+NK1.1+ and CD4+NK1.1− cells. *P < 0.05, infected mouse cells compared with noninfected mouse cells; **P < 0.05, NK1.1+ cells compared with NK1.1− cells. Data are representative of 3 repeat experiments.

The majority of NK1.1+ T cells and a considerable proportion of NK1.1− T cells from the spleen of P. chabaudi-infected mice have an experienced/activated cell phenotype

To further characterize NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells in P. chabaudi-infected mice, CD4+ and CD8+ cells from noninfected mice (controls) and 7-day infected C57BL/6 mice were evaluated according to surface markers highly expressed in experienced (CD44) or activated (CD69 and CD122) cells. Our data showed that NK1.1+ T cells from both groups of mice had similar phenotypes, which was characterized by high levels of CD44 and CD69 in CD4+NK1.1+ and CD8+NK1.1+ cells and of CD122 mostly in CD8+NK1.1+ cells (Fig. 3). On the other hand, around 30% of CD4+NK1.1− and CD8+NK1.1− cells presented high levels of CD44 and CD69, whereas CD122 was expressed mainly in CD8+NK1.1− cells. The great majority of CD4+NK1.1+ and CD4+NK1.1− T cells from 7-day infected mice also presented increased amounts of CD45RB, a molecule highly expressed in naïve and activated cells but down-regulated in memory cells (data not shown). These results showed that the majority of spleen NK1.1+ T cells and a substantial proportion of spleen NK1.1− T cells had an experienced/activated cell phenotype during acute P. chabaudi infection.

FIG. 3.

Expression of CD44, CD69, CD122, and NK1.1 in spleen CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from P. chabaudi-infected C57BL/6 mice. Mice were analyzed at day 7 p.i. with 106 infected red blood cells (iRBCs). Noninfected mice were used as controls. Numbers in dot plots represent the means ± SD (n = 6–8) of the percentages of each subpopulation in gated CD4+ and CD8+ cells. *P < 0.05, infected mouse cells compared with noninfected mouse cells. Data are representative of 4 repeat experiments.

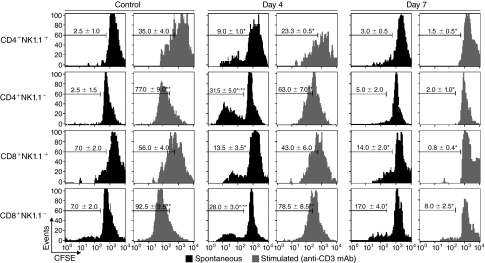

Spleen NK1.1+ T cells from P. chabaudi-infected mice show lower proliferative capacity compared to NK1.1− T cells

To evaluate the proliferative capacity of NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells from P. chabaudi-infected C57BL/6 mice, CFSE-labeled spleen cells obtained at days 4 and 7 p.i. were kept in culture for 72 h alone (spontaneous proliferation) or in the presence of plate-bound anti-CD3 mAbs (stimulated proliferation). NK1.1+ T cells were then compared to NK1.1− T cells, for both CD4+ and CD8+ cell subsets. In uninfected animals, it appears that almost all the NK1.1−T cells have undergone one round of spontaneous cell division under the culture conditions used, while their NK1.1+ counterparts have not (Fig. 4). For the cells taken 4 days after infection, ∼30% of the NK1.1− T cells have gained the ability to proceed through additional rounds of spontaneous proliferation, while most of their NK1.1+ counterparts appear to have undergone either no or only one cell division. At day 7 p.i., the spontaneous proliferation picture seems to resemble the controls, with the exception that the CD8+NK1.1+ cells exhibit a distinct double peak around the 0–1 or 1–2 division's mark. When stimulated with anti-CD3 mAbs, a strong proliferative response occurred at day 0, progressively decreasing after infection, where NK1.1+ T cells always showed lower scores compared to NK1.1− T cells. It is noteworthy that, at day 7 p.i., the percentages of cells proliferating in response to anti-CD3 mAbs were negligible for both NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells. These data showed that spleen NK1.1+ T cells generated during acute P. chabaudi malaria had lower proliferative capacity compared to NK1.1− T cells. They also indicated that T-cell proliferation was tightly regulated a week after infection when the whole T-cell population had impaired response to TCR stimulation.

FIG. 4.

Spontaneous and anti-CD3 mAb-stimulated proliferation of spleen NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells from P. chabaudi-infected C57BL/6 mice. Histograms show in vitro proliferation of CFSE-labeled spleen cells at days 4 and 7 p.i. with 106 infected red blood cells (iRBCs). Noninfected mice were used as controls. Cells were cultured for 72 h alone (spontaneous proliferation) or in the presence of plate-bound anti-CD3 mAbs (stimulated proliferation). Numbers in histograms represent the means ± SD (n = 8) of the percentages of replicating (CFSElow) cells in gated CD4+NK1.1+, CD4+NK1.1−, CD8+NK1.1+, and CD8+NK1.1− cells. *P < 0.05, infected mouse cells compared with noninfected mouse cells; **P < 0.05, NK1.1+ cells compared with NK1.1− cells. Data are representative of 3 repeat experiments.

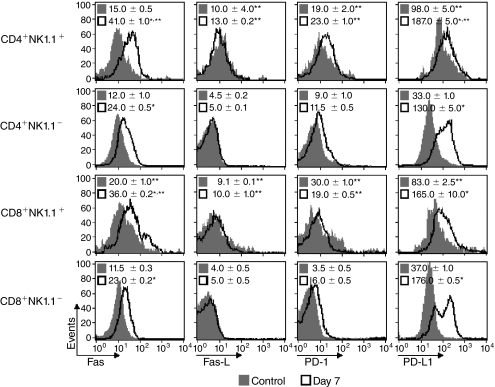

Spleen NK1.1+ T cells from P. chabaudi-infected mice express higher levels of Fas, Fas-L, PD-1, and PD-L1 molecules compared to NK1.1− T cells

Fas–Fas-L (CD95–CD95L) and PD-1–PD-L1 signaling has been shown to abrogate T-cell proliferation through induction of activation-induced cell death (AICD) and dephosphorylation of TCR-associated signaling kinases, respectively (Sharpe and Freeman 2002; Strasser and others 2009). To evaluate the role of these signaling pathways in T-cell proliferation during acute P. chabaudi malaria, the expression of Fas, Fas-L, PD-1, and PD-L1 was compared in NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells from noninfected mice (controls) and 7-day infected C57BL/6 mice. Even before infection, higher levels of all these molecules were detected in CD4+NK1.1+ and CD8+NK1.1+ cells compared to the NK1.1− T-cell subsets (Fig. 5). Moreover, after infection, there was a consistent increase in Fas and PD-L1 expression in CD4+NK1.1− and CD8+NK1.1− cells, whereas differences in Fas-L and PD-1 expression were not statistically significant. It is worth noting that, in most cases, NK1.1+ T cells from 7-day infected C57BL/6 mice showed the highest levels of these molecules, with the exception of PD-L1 molecules in CD8+ cells. These data showed that Fas, Fas-L, PD-1, and PD-L1 were predominantly expressed in spleen NK1.1+ T-cell populations, although Fas and PD-L1 were up-regulated in the majority of T cells at day 7 of infection.

FIG. 5.

Expression of Fas, Fas-L, PD-1, and PD-L1 in spleen NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells from P. chabaudi-infected C57BL/6 mice. Histograms show spleen T cells at days 7 p.i. with 106 infected red blood cells (iRBCs). Noninfected mice were used as controls. Numbers in histograms represent the means ± SD (n = 4–6) of mean fluorescence intensity in gated CD4+NK1.1+, CD4+NK1.1−, CD8+NK1.1+, and CD8+NK1.1− cells. *P < 0.05, noninfected mouse cells compared with infected mouse cells. **P < 0.05, NK1.1+ cells compared with NK1.1− cells. Data are representative of 3 repeat experiments.

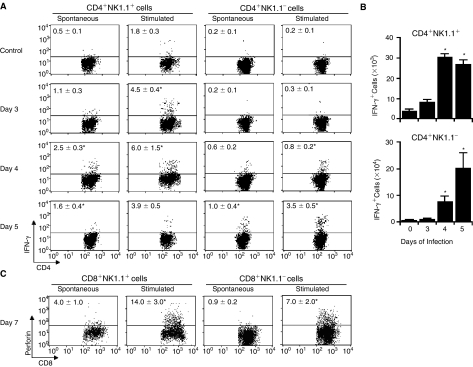

Spleen NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells from P. chabaudi-infected mice produce IFN-γ with different kinetics

To further characterize the phenotype of NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells generated during acute P. chabaudi malaria, IFN-γ and perforin production was evaluated in infected C57BL/6 mice. To compare the kinetics of spontaneous and anti-CD3 mAb-stimulated IFN-γ production by CD4+NK1.1+ and CD4+NK1.1− cells, this analysis was performed at days 3, 4, and 5 of infection. A significant increase in IFN-γ intracellular staining was detected at day 3 p.i., but was only observed in CD4+NK1.1+ cells that had been stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb (Fig. 6A). At day 4 p.i., spontaneous IFN-γ production was significantly enhanced in CD4+NK1.1+ cells, whereas under anti-CD3 mAb stimulation a portion of both CD4+NK1.1+ and CD4+NK1.1− cells was positive. Notably, at this time point, the percentages of IFN-γ+ cells were always higher for CD4+NK1.1+ cells compared to CD4+NK1.1− cells. At day 5 p.i., while IFN-γ+ cell percentages declined within CD4+NK1.1+ cells, an increase of these values was observed within CD4+NK1.1− cells. When CD4+ cell number per spleen was considered, we found 10-fold increase in CD4+NK1.1+IFN-γ+ cell population at day 4 p.i. compared to control, which was remained at similar levels at day 5 p.i. (Fig. 6B). In contrast, the CD4+NK1.1−IFN-γ+ cell population increased 10- and 25-fold at days 4 and 5 p.i., respectively. Because of this different kinetics, around 30% of CD4+IFN-γ+ cells expressed NK1.1 at day 4 p.i., while this proportion fell to nearly 15% at day 5 of infection. For intracellular perforin staining, the percentages of positive cells were significantly higher at day 7 p.i., when 2-fold higher values were detected in CD8+NK1.1+ cells compared to CD8+NK1.1− cells, representing 38% of CD8+perforin+ cells (Fig. 6C). These results showed a different kinetics of IFN-γ production by spleen NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells during acute P. chabaudi infection. These T-cell subpopulations also differ in perforin production.

FIG. 6.

Production of IFN-γ and perforin by spleen T cells from P. chabaudi-infected C57BL/6 mice. (A) Dot plots showing gated CD4+NK1.1+ and CD4+NK1.1− cells stained for intracellular interferon-γ (IFN-γ) in WT mice at days 3, 4, and 5 p.i. with 106 infected red blood cells (iRBCs). Numbers in dot plots represent the means ± SD (n = 4–5) of IFN-γ+ cell percentages. *P < 0.05, infected mouse cells compared with noninfected mouse cells. (B) Numbers of CD4+NK1.1+IFN-γ+ and CD4+NK1.1−IFN-γ+ cells per spleen in mice described in (A). *P < 0.05, infected mice compared with noninfected mice. (C) Dot plots showing gated CD8+NK1.1+ and CD8+NK1.1− cells stained for intracellular perforin at day 7 p.i. with 106 iRBC. Numbers in dot plots represent the means ± SD (n = 4–5) of perforin+ cell percentages. *P < 0.05, infected mouse cells compared with noninfected mouse cells. In (A–C), cells were cultured for 10 h alone (spontaneous production) or in the presence of plate-bound anti-CD3 mAbs (stimulated production). Noninfected mice were used as controls. Data are representative of 3 repeat experiments.

Discussion

We have previously observed that a considerable proportion of spleen T cells express the NK1.1 molecule during the acute phase of blood-stage P. chabaudi AS infection. To investigate the role of these lymphocyte subpopulations, we have compared spleen NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T-cell responses at the early infection. Our results have shown that these T-cell subpopulations respond to parasites with different kinetics in terms of activation, proliferation, and IFN-γ production.

In our study, most CD4+NK1.1+ and CD8+NK1.1+ T cells observed in the spleen of acutely infected mice present the characteristic phenotype of activated/experienced cells, expressing high levels of CD44, CD69, and CD122 (mainly for CD8+ cells). A similar phenotype has also been described in liver NK1.1+ T cells from P. yoelii-infected mice (Pied and others 2000; Soulard and others 2007). Although in our study CD4+NK1.1+ T cells can be restricted by CD1d, they are not iNKT cells since they do not recognize the CD1d-αGalCer tetramer and do not preferentially use the TCR-Vβ8 molecule. The possibility that upon activation iNKT cells have down-regulated the expression of their invariant TCR, making difficult their identification (Wilson and others 2003), is unlikely taking into account the high levels of TCR molecules expressed in spleen CD4+NK1.1+ T cells from the acute infection. In agreement with these findings, Soulard and collaborators showed that the iNKT cell population from the liver, but not the spleen, is expanded in P. yoelii infection (Soulard and others 2007). Yet, our data showing that NK1.1+ T cells in P. chabaudi-infected mice and iNKT cells in noninfected mice present similar phenotypes suggests that these populations share common effector functions, despite having different specificities. This is an interesting observation since most studies on this subject address type I NKT cells (iNKT cells) and much less is known about type II NKT cells, which express more diverse TCRs and therefore are difficult to characterize (Godfrey and Berzins 2007).

Another interesting finding of our study is that spleen NK1.1− T cells proliferate vigorously at day 4 p.i. but still respond to further TCR signaling, while at day 7 p.i. both T-cell subsets fail to proliferate even after strong TCR stimulation. Although the molecular mechanism involved in the early T-cell response to P. chabaudi is poorly understood, these results indicate that spleen T cells undergo a well-defined cell program that allows intense proliferation at the first day of infection, which is followed by tight regulation of this response at the peak of parasitemia. The expression of regulatory molecules on T cells may be responsible for limiting this proliferative response since they are increased in acutely infected mice. Indeed, NK1.1+ T cells seem to be highly regulated regardless if they are taken from noninfected or infected mice. According to our data, these cells show lower spontaneous and TCR-stimulated proliferation compared to NK1.1− T cells, which correlates with higher surface levels of Fas, Fas-L, PD-1, and PD-L1 molecules. At day 7 p.i., the increase in expression of Fas and PD-L1 by NK1.1− T cells is also associated with impaired proliferative response. IL-2, a cytokine produced during the early infection (Zago and others, manuscript in preparation), could be responsible for inducing these regulatory molecules since it participates in both Fas–Fas-L-mediated AICD (Hoyer and others 2008) and PD-1–PD-L1-mediated unresponsiveness (Kinter and others 2008). IL-2 production could also be involved in the increase of NK1.1 molecules in spleen T cells from P. chabaudi-infected mice since in vitro stimulation of CD8+ T cells by IL-2 is able to up-regulate NK1.1 expression on the cell surface and these IL-2-induced CD8+NK1.1+ T cells are not iNKT cells (Assarsson and others 2000).

The Fas–Fas-L pathway is involved in the apoptosis of spleen lymphocytes during acute P. chabaudi infection, which may contribute to homeostasis of the immune system (Helmby and others 2000; Sanchez-Torres and others 2001; Xu and others 2002; Elias and others 2005). Although we have shown that apoptosis induced by high acute-phase parasitemias does not prevent the generation of memory T and B cells (Freitas do Rosario and others 2008), it can certainly hinder the strength of specific immunity to the parasite (Xu and others 2002; Elliott and others 2005). On the other hand, the PD-1–PD-L1 pathway may also minimize immune-mediated damage to the host by suppressing certain effectors functions upon TCR engagement, without interfering with cytokine-driven T-cell expansion/survival (Kinter and others 2008). Because of this, we can envisage that high expression of PD-L1 in both NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells from 7-day infected mice is a potent molecular mechanism to avoid further TCR-mediated T-cell signaling. This could protect mice from the deleterious effects of over activation of the immune system, allowing the development of memory T cells through cytokine-driven survival signals. To the best of our knowledge, the PD-1 and PD-L1 data presented here are the first descriptions of changes in these molecules during malaria, and experiments using blocking antibodies are currently in progress to determine their role in the regulation of immune response to acute P. chabaudi infection.

Spleen NK1.1+ T cells induced during early P. chabaudi infection present an experienced/activated phenotype, expressing high levels of activation molecules (CD69 and CD122) and producing IFN-γ and perforin. Corroborating our results, spleen NK1.1+TCR-β+ cells from P. yoelii-infected mice are biased toward the capacity to produce TNF-α and IFN-γ but not IL-4 (Soulard and others 2007). Most importantly, our results showing different kinetics of IFN-γ production between spleen CD4+NK1.1+ and CD4+NK1.1− T cells, with an earlier response of cells expressing NK1.1, support the notion that these cells belong to distinct T-cell subsets. Furthermore, the rapid decrease in the proportion of IFN-γ-producing CD4+NK1.1+ T cells from day 4 to 5 p.i. indicates that the effector role of this population is restricted to the first days of infection, whereas the importance of CD4+NK1.1− T cells increases with time. Similarly to these results, both NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells have been associated with resistance to P. yoelii parasites (Pied and others 2000; Mannoor and others 2001; Soulard and others 2007), where the involvement of NK1.1+ T cells is larger at day 5 p.i. and decreases thereafter (Soulard and others 2009). Thus, the main contribution of spleen CD4+NK1.1+ cells in murine malaria appears to be related to their capacity to rapidly sense the infection, which may accelerate the activation of other cells from the immune system, guaranteeing an optimized parasite control. Corroborating this notion, it has been recently shown that the cross talk between dendritic cells and NK cells is of major importance for induction of an efficient Th1 cell priming and resolution of P. chabaudi infection (Ing and others 2009).

The involvement of perforin-producing CD8+NK1.1+ cells in protection against blood stages of P. chabaudi seems unlikely given the lack of MHC class I molecules in erythrocytes. Even so, it has been shown that NKT cells can mediate P. berghei-induced liver injury by a mechanism that is independent of CD1d- and MHC-restricted interactions (Adachi and others 2004). On the other hand, perforin-mediated CD8+ T-cell cytotoxicity is known to participate in P. berghei ANKA malaria pathogenesis since mice lacking this molecule are protected from development of cerebral malaria (Nitcheu and others 2003). Likewise, CD8+ T cells have been implicated in the immune-mediated pathology of the spleen as a result of P. chabaudi infection, by determining the loss of marginal metallophilic macrophages (Beattie and others 2006). The role of perforin-producing CD8+NK1.1+ cells in these processes remains to be established.

We believe that this analysis will help to further establish the relative contribution of NK1.1+ and NK1.1− T cells in mediating the immune response during acute Plasmodium infection. This knowledge can help to improve our understanding on the complex network of innate and adaptive immune cells required for both parasite control and development of malaria syndromes. Characterizing the immunological mechanisms responsible for different outcomes of malaria can improve strategies aimed at eliciting protection against disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Meire Ioshie Hiyane and Rogério Silva Nascimento for technical assistance and Dr. Mitchell Kronenberg and NIH (National Institutes of Health—USA) Tetramer Facility for providing the CD1d-α-GalCer tetramer. This study was supported by FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo—Brazil) and CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico—Brazil).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Adachi K. Tsutsui H. Seki E. Nakano H. Takeda K. Okumura K. Van Kaer L. Nakanishi K. Contribution of CD1d-unrestricted hepatic DX5+ NKT cells to liver injury in Plasmodium berghei-parasitized erythrocyte-injected mice. Int Immunol. 2004;16(6):787–798. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arase H. Arase N. Saito T. Interferon gamma production by natural killer (NK) cells and NK1.1+ T cells upon NKR-P1 cross-linking. J Exp Med. 1996;183(5):2391–2396. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arase N. Arase H. Park SY. Ohno H. Ra C. Saito T. Association with FcRgamma is essential for activation signal through NKR-P1 (CD161) in natural killer (NK) cells and NK1.1+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186(12):1957–1963. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.12.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assarsson E. Kambayashi T. Sandberg JK. Hong S. Taniguchi M. Van Kaer L. Ljunggren HG. Chambers BJ. CD8+ T cells rapidly acquire NK1.1 and NK cell-associated molecules upon stimulation in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;165(7):3673–3679. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie L. Engwerda CR. Wykes M. Good MF. CD8+ T lymphocyte-mediated loss of marginal metallophilic macrophages following infection with Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi AS. J Immunol. 2006;177(4):2518–2526. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendelac A. Lantz O. Quimby ME. Yewdell JW. Bennink JR. Brutkiewicz RR. CD1 recognition by mouse NK1+ T lymphocytes. Science. 1995;268(5212):863–865. doi: 10.1126/science.7538697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. Huang H. Paul WE. NK1.1+ CD4+ T cells lose NK1.1 expression upon in vitro activation. J Immunol. 1997;158(11):5112–5119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark IA. Budd AC. Alleva LM. Cowden WB. Human malarial disease: a consequence of inflammatory cytokine release. Malar J. 2006;5:85. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. Semoff S. Hommel M. Plasmodium chabaudi: a rodent malaria model for in-vivo and in-vitro cytoadherence of malaria parasites in the absence of knobs. Parasite Immunol. 1987;9(5):543–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1987.tb00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Imperio Lima MR. Alvarez JM. Furtado GC. Kipnis TL. Coutinho A. Minoprio P. Ig-isotype patterns of primary and secondary B cell responses to Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi correlate with IFN-gamma and IL-4 cytokine production with CD45RB expression by CD4+ spleen cells. Scand J Immunol. 1996;43(3):263–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1996.d01-35.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias RM. Sardinha LR. Bastos KR. Zago CA. da Silva AP. Alvarez JM. Lima MR. Role of CD28 in polyclonal and specific T and B cell responses required for protection against blood stage malaria. J Immunol. 2005;174(2):790–799. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott SR. Kuns RD. Good MF. Heterologous immunity in the absence of variant-specific antibodies after exposure to subpatent infection with blood-stage malaria. Infect Immun. 2005;73(4):2478–2485. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2478-2485.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falanga PB. D'Imperio Lima MR. Coutinho A. Pereira da Silva L. Isotypic pattern of the polyclonal B cell response during primary infection by Plasmodium chabaudi and in immune-protected mice. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17(5):599–603. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830170504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas do Rosario AP. Muxel SM. Rodriguez-Malaga SM. Sardinha LR. Zago CA. Castillo-Mendez SI. Alvarez JM. D'Imperio Lima MR. Gradual decline in malaria-specific memory T cell responses leads to failure to maintain long-term protective immunity to Plasmodium chabaudi AS despite persistence of B cell memory and circulating antibody. J Immunol. 2008;181(12):8344–8355. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DI. Berzins SP. Control points in NKT-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(7):505–518. doi: 10.1038/nri2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DI. Hammond KJ. Poulton LD. Smyth MJ. Baxter AG. NKT cells: facts, functions and fallacies. Immunol Today. 2000;21(11):573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01735-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DI. MacDonald HR. Kronenberg M. Smyth MJ. Van Kaer L. NKT cells: what's in a name? Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(3):231–237. doi: 10.1038/nri1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmby H. Jonsson G. Troye-Blomberg M. Cellular changes and apoptosis in the spleens and peripheral blood of mice infected with blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi AS. Infect Immun. 2000;68(3):1485–1490. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1485-1490.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer KK. Dooms H. Barron L. Abbas AK. Interleukin-2 in the development and control of inflammatory disease. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntington ND. Vosshenrich CA. Di Santo JP. Developmental pathways that generate natural-killer-cell diversity in mice and humans. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(9):703–714. doi: 10.1038/nri2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ing R. Stevenson MM. Dendritic cell and NK cell reciprocal cross talk promotes gamma interferon-dependent immunity to blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi AS infection in mice. Infect Immun. 2009;77(2):770–782. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00994-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T. Cui J. Koezuka Y. Toura I. Kaneko Y. Motoki K. Ueno H. Nakagawa R. Sato H. Kondo E. Koseki H. Taniguchi M. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of valpha14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278(5343):1626–1629. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinter AL. Godbout EJ. McNally JP. Sereti I. Roby GA. O'Shea MA. Fauci AS. The common gamma-chain cytokines IL-2, IL-7, IL-15, and IL-21 induce the expression of programmed death-1 and its ligands. J Immunol. 2008;181(10):6738–6746. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhorne J. Gillard S. Simon B. Slade S. Eichmann K. Frequencies of CD4+ T cells reactive with Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi: distinct response kinetics for cells with Th1 and Th2 characteristics during infection. Int Immunol. 1989;1(4):416–424. doi: 10.1093/intimm/1.4.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima MR. Bandeira A. Falanga P. Freitas AA. Kipnis TL. da Silva LP. Coutinho A. Clonal analysis of B lymphocyte responses to Plasmodium chabaudi infection of normal and immunoprotected mice. Int Immunol. 1991;3(12):1207–1216. doi: 10.1093/intimm/3.12.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannoor MK. Weerasinghe A. Halder RC. Reza S. Morshed M. Ariyasinghe A. Watanabe H. Sekikawa H. Abo T. Resistance to malarial infection is achieved by the cooperation of NK1.1(+) and NK1.1(−) subsets of intermediate TCR cells which are constituents of innate immunity. Cell Immunol. 2001;211(2):96–104. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mota MM. Brown KN. Holder AA. Jarra W. Acute Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi malaria infection induces antibodies which bind to the surfaces of parasitized erythrocytes and promote their phagocytosis by macrophages in vitro. Infect Immun. 1998;66(9):4080–4086. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4080-4086.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitcheu J. Bonduelle O. Combadiere C. Tefit M. Seilhean D. Mazier D. Combadiere B. Perforin-dependent brain-infiltrating cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes mediate experimental cerebral malaria pathogenesis. J Immunol. 2003;170(4):2221–2228. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pied S. Roland J. Louise A. Voegtle D. Soulard V. Mazier D. Cazenave PA. Liver CD4-CD8− NK1.1+ TCR alpha beta intermediate cells increase during experimental malaria infection and are able to exhibit inhibitory activity against the parasite liver stage in vitro. J Immunol. 2000;164(3):1463–1469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Torres L. Rodriguez-Ropon A. Aguilar-Medina M. Favila-Castillo L. Mouse splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells undergo extensive apoptosis during a Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi AS infection. Parasite Immunol. 2001;23(12):617–626. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2001.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmieg J. Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza G. Tsuji M. The role of natural killer T cells and other T cell subsets against infection by the pre-erythrocytic stages of malaria parasites. Microbes Infect. 2003;5(6):499–506. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield L. Grau GE. Immunological processes in malaria pathogenesis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(9):722–735. doi: 10.1038/nri1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe AH. Freeman GJ. The B7-CD28 superfamily. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(2):116–126. doi: 10.1038/nri727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slifka MK. Pagarigan RR. Whitton JL. NK markers are expressed on a high percentage of virus-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2000;164(4):2009–2015. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulard V. Roland J. Gorgette O. Barbier E. Cazenave PA. Pied S. An early burst of IFN-gamma induced by the pre-erythrocytic stage favours Plasmodium yoelii parasitaemia in B6 mice. Malar J. 2009;8:128. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulard V. Roland J. Sellier C. Gruner AC. Leite-de-Moraes M. Franetich JF. Renia L. Cazenave PA. Pied S. Primary infection of C57BL/6 mice with Plasmodium yoelii induces a heterogeneous response of NKT cells. Infect Immun. 2007;75(5):2511–2522. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01818-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson MM. Tam MF. Belosevic M. van der Meide PH. Podoba JE. Role of endogenous gamma interferon in host response to infection with blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi AS. Infect Immun. 1990;58(10):3225–3232. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3225-3232.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser A. Jost PJ. Nagata S. The many roles of FAS receptor signaling in the immune system. Immunity. 2009;30(2):180–192. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Malaria, other vectorborne and parasitic diseases: Regional trend in cases and deaths. 2007. http://www.wpro.who.int/sites/mvp/data/ http://www.wpro.who.int/sites/mvp/data/

- Wilson MT. Johansson C. Olivares-Villagomez D. Singh AK. Stanic AK. Wang CR. Joyce S. Wick MJ. Van Kaer L. The response of natural killer T cells to glycolipid antigens is characterized by surface receptor down-modulation and expansion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):10913–10918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1833166100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H. Wipasa J. Yan H. Zeng M. Makobongo MO. Finkelman FD. Kelso A. Good MF. The mechanism and significance of deletion of parasite-specific CD4(+) T cells in malaria infection. J Exp Med. 2002;195(7):881–892. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]