Abstract

A facile chemical reduction method has been developed to fabricate ultrafine copper nanoparticles whose sizes can be controlled down to ca. 1 nm by using poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP) as the stabilizer and sodium borohyrdride as the reducing agent in an alkaline ethylene glycol (EG) solvent. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) results and UV–vis absorption spectra demonstrated that the as-prepared particles were well monodispersed, mostly composed of pure metallic Cu nanocrystals and extremely stable over extended period of simply sealed storage.

Keywords: Copper nanoparticles, Ultrafine nanoparticles, Chemical reduction, Polyol method

Introduction

Nanoparticles of the coinage metals have raised great attention due to their fascinating optical, electronic, and catalytic properties [1-3]. In the last two decades, a substantial body of research has been directed toward the synthesis and application of Au and Ag nanoparticles. Brilliant achievements have been made toward the successful control of the nanoparticle sizes and shapes [4], and the broad applications in optical waveguides [1], catalysis [2], surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) [3], and surface-enhanced IR absorption spectroscopy (SEIRAS) [5,6]. Copper is a highly conductive, much cheaper, and industrially widely used material, possessing a valence shell electron structure similar to the other two coinage metals. Furthermore, it is unique with the chemical reactivity capable of serving as precursors for the fabrication of conductive structures by ink-jet printing [7] or forming CuInSe2 or CuInxGa1−xSe2 semiconducting nanomaterials for photodetectors and photovoltaics [8]. Nevertheless, over the years, fabrication of Cu nanoparticles has received less attention as compared to that of Au and Ag ones [7,9-17], and is still open for more intensive investigations.

Several methods have been developed for the preparation of copper nanoparticles, including thermal reduction [9], sonochemical reduction [13], metal vapor synthesis [10], chemical reduction [7,11,14,15], vacuum vapor deposition [12], radiation methods [16], and microemulsion techniques [17]. Among all these methods as mentioned, chemical reduction in aqueous or organic solvents exhibits the greatest feasibility to be extended to further applications in terms of its simplicity and low cost. However, Cu nanoparticles so far obtained via the chemical reduction tactics are mostly located in the range of 10–50 nm, and well dispersed Cu nanoparticles with a mean diameter of 5.1 nm could only be synthesized in a CTAB solution [14]. As is well known, the chemical and physical properties including catalytic activities and melting points of the metal nanoparticles are significantly influenced by the particle size [7]. Along this line, synthesis of copper nanoparticles with smaller sizes based on simple chemical reduction is highly demanded.

Here, we present a facile fabrication of ultrafine and monodispersed copper nanoparticles in an organic solvent with average diameters down to 1.4 ± 0.6 nm. The whole synthesis was just taken at room temperature under nitrogen atmosphere. Poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP) was used as the stabilizer and sodium borohyrdride as the main reducing agent in the alkaline solvent. Ethylene glycol (EG) was chosen as the solvent for better preventing the oxidation and aggregation of the nanoparticles. The characterization of the Cu colloids was accomplished by using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) as well as UV–vis spectroscopy.

Experimental Section

Preparation of Copper Nanoparticles

Synthesis of ultrafine copper nanoparticles in organic solvent was typically processed as follows. A certain amount of poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP, MW = 55,000), acting as the capping molecule, was dissolved in ethylene glycol (EG) in a flask. Afterward, at room temperature, copper(II) sulfate (1.5 ml of a 0.1 M solution in EG) was added under strong magnetic stirring followed by adjusting the solution pH up to 11 with dropwise addition of 1 M NaOH EG solution. After stirring for an additional 10 min, 4 ml of 0.5 M NaBH4EG solution was quickly added into the flask. In the first few minutes, the deep blue solution gradually became colorless, and then it turned burgundy, suggestive of the formation of a copper colloid. All procedures were carried out with nitrogen gas bubbling to prevent the reoxidation of reduced copper.

Characterization

The ultrafine copper nanoparticles were characterized using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (JEOL JEM-2010) with an accelerating voltage of 100 kV. TEM samples were prepared by placing a drop of a dilute dispersion of Cu nanoparticles on the surface of a 400-mesh copper grid backed with Formvar and were dried in a vacuum chamber for 20 min. The UV–vis absorbance was measured on a PerkinElmer LAMBDA 40 spectrometer.

Results and Discussion

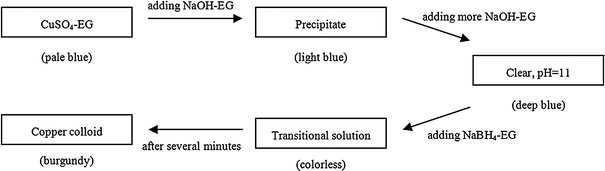

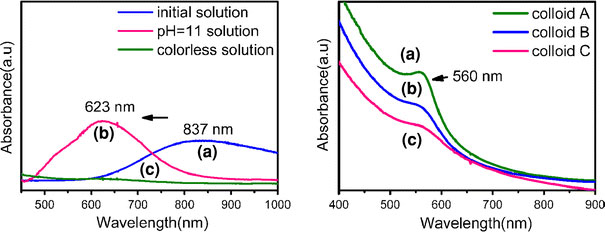

During synthesis, the dropwise addition of NaOH-EG solution to the pale blue CuSO4-EG bulk solution resulted initially in the formation of a white blue precipitate attributable likely to Cu(OH)2. Then, this precipitate gradually dissolved and turned to a deep blue clear solution with further addition of NaOH to reach pH 11, as clearly demonstrated by the significant blueshift of ca. 214 nm in absorption peak of the relevant solutions (seecurves aandbin the left panel of Fig. 1). In considering that hydroxide ions and ethylene glycol may coordinate with copper ions, we assume that an intermediate Cu(II)-hydroxyl-EG complex may form at this stage before it is reduced by NaBH4. Addition of NaBH4-EG solution first turned the deep blue solution to a nearly colorless one (seecurve cin the left panel of Fig. 1), and eventually to a burgundy one (see curves in the right panel of Fig. 1). The above colorless solution can be explained if we assume that Cu(I) species is formed at this stage, since the d–d transitions would be forbidden due to a full electronic structure in the 3d orbital of Cu(I) species. The final burgundy solution can be assigned to the Cu colloid (vide infra). Along this line, we may conclude that the reduction proceeds through Cu(II) → Cu(I) → Cu(0). The flow chart of color changes during the synthesis depicted in Chart 1, for a better visual understanding.

FigureChart 1.

The flow chart showing the synthesis procedure and related color variations

The right panel of Fig. 2 shows the UV–vis absorption spectra of three colloidal solutions synthesized under otherwise the same conditions except differences in molecular ratios of PVP (counted as the repeat union) and CuSO4, viz. 2:1, 10:1, and 20:1 (designated as colloids A, B, and C). A band centered at ca. 560 nm for each solution can be seen, characteristic of surface plasmon absorption of copper colloids. In addition, no enhanced background absorption around 800 nm can be observed implicating that the colloidal particles are nominally reduced copper in nature without being oxidized to copper oxide on surface [17-19]. The as-prepared Cu colloids exhibit a blueshift of ca. 10 nm in absorption peak as compared to the previously reported Cu colloid [14], suggestive of much smaller particle sizes [20]. The peak position incurve a is redshifted by ca. 2 nm with respect tocurves b andc, while the corresponding peak intensity decreases apparently from colloid A to C, revealing that the particle size decreases with increasing molecular ratio of PVP and CuSO4 as predicted by the Mie’s theory [19]. Notably, no precipitation was observed and the UV–vis absorption profile remained virtually unchanged even after 2 months storage in a simply sealed container, suggestive of long-term stability of the as-prepared Cu colloids.

Figure 1.

Left panel: UV–vis absorption spectra of (a) CuSO4EG solution, (b) pH 11solution, and (c) transitional colorless solution. Right panel: UV–vis absorption spectra of copper colloids A, B, and C, which are synthesized under different molecular ratios of PVP and CuSO4, viz., (a) 2:1, (b) 10:1, and (c) 20:1, respectively

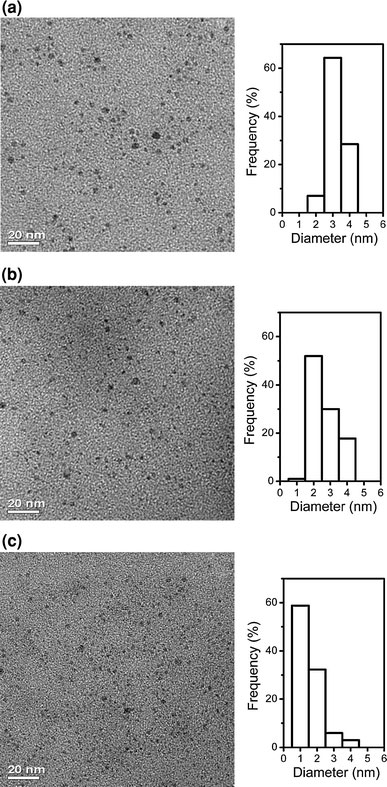

Figure 3 are the TEM images for Cu nanoparticles from colloids A, B, and C together with the histograms of particle size distributions, indicating that Cu nanoparticles are rather monodispersed in nearly sphere shape. Careful statistical examination of the nanoparticles revealed that average sizes of 3.1 ± 0.5 nm, 2.6 ± 0.6 nm, and 1.4 ± 0.6 nm were for colloids A, B, and C, respectively, in agreement with the UV–vis results. As PVP molecules strongly adsorb on as-prepared metal nanoparticles, they effectively prevent the aggregation in reducing metal ions [21-23]. Consequently, at a higher molecular ratio of PVP and CuSO4, more PVP molecules are adsorbed on Cu nanoparticle surfaces, keeping them from the excessive growth, and leading to the formation of smaller nanoparticles.

Figure 2.

TEM images and corresponding histograms of copper colloid (a) A, (b) B, and (c) C, respectively

It should be pointed out that in a traditional polyol process to obtain metal nanoparticles, EG acts not only as an organic solvent but also as a reducing agent [24]. The use of EG to reduce Cu(II) species at a relative high temperature would produce Cu nanoparticles >30 nm due to its inherently mild reducing ability [7]. At room temperature, EG is unlikely involved in the reduction of Cu(II) species, and the introduction of a much stronger reducing agent is believed to be a crucial factor for achieving much smaller particle sizes, given that the nucleation and growth processes are greatly dependent on the power of reducing agent [15]. Briefly, weaker reducing agents benefit further growth of the existing nuclei leading to larger particles. With stronger reducing agent, the larger nucleation probability would be expected, in favor of the formation of more ultrafine nanoparticles.

Along this line, the use of stronger reducing agent NaBH4played an important role as well in the controlled synthesis of ultrafine copper nanoparticles in this study. The reduction ability of NaBH4is related to its concentration and the solution pH. For a given concentration, the solution pH should be properly regulated to attain a satisfactory size control. We found that for 0.5 M NaBH4, pH 11 was optimized for the fabrication of ultrafine copper nanoparticles. At too low pH, rapid release of strong hydrogen bubbles produces large amount of Cu nuclei, which tend to aggregate into large agglomerates; at too high pH, newly reduced Cu atoms prefer to deposit onto the nuclei already formed, eventually causing larger Cu nanoparticles.

Conclusions

In summary, nominally reduced Cu nanoparticles was synthesized by a modified polyol method, leading to ultrafine nanoparticles ranging from 1.4 ± 0.6 nm to 3.1 ± 0.5 nm in average with narrow size distribution, uniform shape, and great stability. The size of the nanoparticles decreases with increasing the ratio of PVP and Cu(II) concentrations in the precursor solution by using NaBH4as the reducing agent. The organic solution EG, stabilizer PVP, and the pH value showed a co-effect to ensure the formation of the desired particles, and the reduction process may go through Cu(II) → Cu(I) → Cu(0).

Contributor Information

Han-Xuan Zhang, Email: 082022032@fudan.edu.cn.

Uwe Siegert, Email: uwe.siegert@s2000.tu-chemnitz.de.

Ran Liu, Email: rliu@fudan.edu.cn.

Wen-Bin Cai, Email: wbcai@fudan.edu.cn.

Acknowledgment

This work is supported by the NSFC (Nos. 20673027 and 20833005) and Sino-German IRTG program.

References

- Oldenburg SJ, Averitt RD, Westcott SL, Halas NJ. Chem Phys Lett. 1998. p. 243. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK1cXjtVamtLY%3D]; Bibcode number [1998CPL...288..243O] [DOI]

- Henglein A. J Phys Chem B. 2000. p. 6683. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3cXktlOrurk%3D] [DOI]

- Michaels AM, Jiang J, Brus L. J Phys Chem B. 2000. p. 11965. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3cXot1Khu7Y%3D] [DOI]

- Sun YG, Xia YN. Science. 2002. p. 2176. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD38XpsVSkt7Y%3D]; Bibcode number [2002Sci...298.2176S] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Huo SJ, Li QX, Yan YG, Chen Y, Cai WB, Xu QJ, Osawa M. J Phys Chem B. 2005. p. 15985. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2MXmvVCrsrg%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Huo SJ, Xue XK, Li QX, Xu SF, Cai WB. J Phys Chem B. 2006. p. 25721. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD28Xht1anurnN] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jeong S, Woo K, Kim D, Lim S, Kim JS, Shin H, Xia Y, Moon J. Adv Funct Mater. 2008. p. 679. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1cXktFGis70%3D] [DOI]

- Tang J, Hinds S, Kelley SO, Sargent EH. Chem Mater. 2008. p. 6906. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1cXhtlSqtLnN] [DOI]

- Dhas NA, Raj CP, Gedanken A. Chem Mater. 1998. p. 1446. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK1cXis12nt7o%3D] [DOI]

- Vitulli G, Bernini M, Bertozzi S, Pitzalis E, Salvadori P, Coluccia S, Martra G. Chem Mater. 2002. p. 1183. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD38XhsFait7g%3D] [DOI]

- Huang HH, Yan FQ, Kek YM, Chew CH, Xu GQ, Ji W, Oh PS, Tang SH. Langmuir. 1997. p. 172. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK2sXktlan] [DOI]

- Liu ZW, Bando Y. Adv Mater. 2003. p. 303. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3sXitlOjsr8%3D] [DOI]

- Kumar RV, Mastai Y, Diamant Y, Gedanken A. J Mater Chem. 2001. p. 1209. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3MXit1Gis78%3D] [DOI]

- Wu SH, Chen DH. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2004. p. 165. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXisFCns7g%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Park BK, Jeong S, Kim D, Moon J, Lim S, Kim JS. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2007. p. 417. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2sXlsFansrw%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Casella IG, Cataldi TRI, Guerrieri A, Desimoni E. Anal Chim Acta. 1996. p. 217. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK28Xnt1Kmu7s%3D] [DOI]

- Lisiecki I, Pileni MP. J Am Chem Soc. 1993. p. 3887. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK3sXisVWksLo%3D] [DOI]

- Yanase A, Komiyama H. Surf Sci. 1991. p. 11. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK3MXltVShs7s%3D]; Bibcode number [1991SurSc.248...11Y] [DOI]

- Lisiecki I, Billoudet F, Pileni MP. J Phys Chem. 1996. p. 4160. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK28XhtVKksb8%3D] [DOI]

- Shirtcliffe N, Nickel U, Schneider S. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1999. p. 122. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK1MXhtlOlsLk%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jiang P, Li SY, Xie SS, Gao Y, Song L. Chem Eur J. 2004. p. 4817. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXoslegu78%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shin HS, Yang HJ, Kim SB, Lee MS. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2004. p. 89. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXjsFOgs78%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang ZT, Zhao B, Hu LM. J Solid State Chem. 1996. p. 105. COI number [1:CAS:528:DyaK28Xpt1Wqug%3D%3D]; Bibcode number [1996JSSCh.121..105Z] [DOI]

- Bock C, Paquet C, Couillard M, Botton GA, MacDougall BR. J Am Chem Soc. 2004. p. 8028. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXksVGqtro%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]