Abstract

d-3-Deoxy-phosphatidylinositol derivatives have cytotoxic activity against various human cancer cell lines. These phosphatidylinositols have a potentially wide array of targets in the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling network. To explore the specificity of these types of molecules, we have synthesized d-3-deoxy-dioctanoylphosphatidylinositol (d-3-deoxy-diC8PI), d-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI and d-3-deoxy-dioctanoylphosphatidylinositol-5-phosphate and their enantiomers, characterized their aggregate formation by novel high resolution field cycling 31P NMR, and examined their susceptibility to phospholipase C (PLC) and their effects on the catalytic activity of PI3K and PTEN against diC8PI and dioctanoylphosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate substrates, respectively, as well as their ability to induce the death of the U937 human leukemic monocyte lymphoma cells. Of these molecules, only d-3-deoxy-diC8PI was able to promote cell death; it did so with an IC50 of 40 μM, well below the CMC of 0.4 mM. Under these conditions, there was little inhibition of PI3K or PTEN observed in assays of recombinant enzymes (although the complete series of deoxy-PI compounds did provide insights into ligand binding by PTEN). The d-3-deoxy-diC8PI was a poor substrate and not an inhibitor of the PLC enzymes. The in vivo results are consistent with the current thought that the PI analogue acts on Akt1 since the transcription initiation factor eIF4e, which is a downstream signaling target of the PI3K/Akt pathway, exhibited reduced phosphorylation on Ser209. Phosphorylation of Akt1 on Ser473, but not Thr308, was reduced. Since the potent cytotoxicity for U937 cells is completely lost with the l-3-deoxy-diC8PI as well as with modification of the hydroxyl group at the inositol C5 (either replacing the –OH with a hydrogen or phosphorylating it) in d-3-deoxy-diC8PI, both chirality of the phosphoinositol moiety and the hydroxyl group at C5 are major determinants of 3-deoxy-PI binding to its target in cells.

Keywords: 3-deoxyphosphatidylinositol, PTEN, field cycling NMR, short-chain phospholipids, U937 cells

INTRODUCTION

The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3Ka) / Akt (or protein kinase B) signaling pathway is critical for cell survival and upregulated in a variety of human cancer cell lines1 and solid tumors. 2-4 A key step in this pathway is the specific phosphorylation of the 3-hydroxyl group of the inositol ring in phosphoinositides by PI3K enzymes. These lipid products affect cell growth by binding specifically to enzymes such as Akt and recruiting them to the membrane for activation by phosphorylation.5-7 The activated Akt survival signal in cells stems from its phosphorylation and inactivation of pro-apoptosis proteins. Counterbalancing PI3K is the lipid phosphatase PTEN, which specifically dephosphorylates the 3-phosphate and in so doing inhibits PI3K/Akt signaling.8 Indeed, mutations of PTEN have been reported in an array of human tumors.9,10

Attempts to inhibit the PI3K/Akt pathway led to the synthesis of d-3-deoxy-phosphatidylinositol molecules that can no longer be phosphorylated by PI3K (for a review see Gills and Dennis (2004).11 Many of these molecules have antiproliferative properties.12,13 The first of these, 3-deoxy-dipalmitoyl-PI, was shown to inhibit cancer cell (HT-29 human colon carcinoma) growth in vitro with an IC50 of 35 μM.12 Recent syntheses of ether linked rather than ester linked alkyl chains, e.g., d-3-deoxy-myo-inositol 1-[(R)-3-(hexadecyloxy)-2-hydroxypropyl hydrogen phosphate], have generated a newer class of PI analogues that should have higher stability in vivo and may also have slightly better delivery properties since they are more like lyso-phospholipids.14 3-Deoxy-PIs have also been shown to reduce drug resistance in human leukemia cell lines.15 Thus, these PI analogues may have a future in treatment of a variety of cancers.

The proposed mechanism for inhibition of cell growth by deoxy-PIs is rather curious. Previous work suggested that rather than inhibit PI3K, the 3-deoxy-PI compounds inhibit the serine/threonine protein kinase Akt by binding tightly to its PH domain, which normally binds PI(3,4)P2 or PI(3,4,5), and trapping it in the cytoplasm, thereby preventing phosphorylation by effector kinases.7 The spectrum of changes in cells caused by these 3-deoxy-PI molecules differs from other widely studied cell growth inhibitors.16 Interestingly, their patterns of activity are most like other lipid-based compounds (e.g., miltefosine and perifosine), which do not contain inositol moieties and also appear to inhibit Akt translocation and phosphorylation,17,18 and distinct from other compounds known to inhibit the PI3K/Akt pathway.

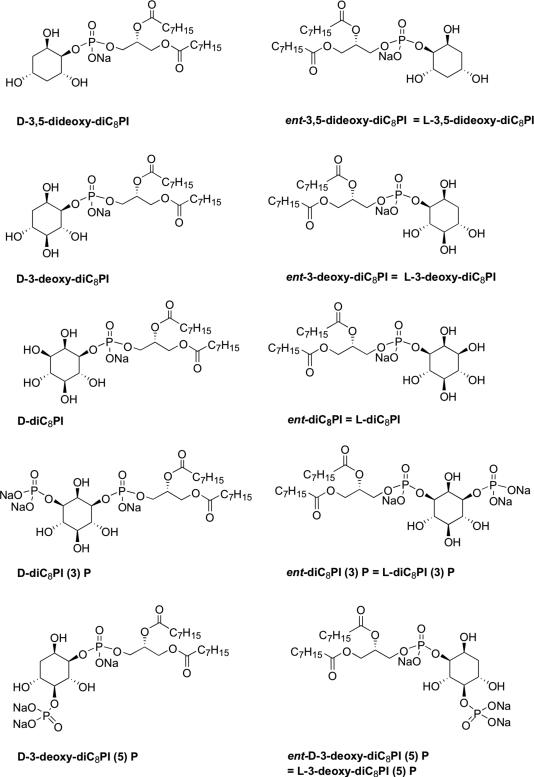

Significant synthetic effort has been used to modify the d-inositol ring to improve its cytotoxicity,19 but little has been done to explore broader changes in the stereochemistry of the inositol ring or systematically employing further deoxygenation20, 21 to assess specific interactions of 3-deoxy-PI molecules with targets. Modulating inhibitor solubility by shortening acyl chains so that it can exist as monomers may also contribute to understanding mechanisms of action of these lipids, since this modification is likely to alter uptake and localization in the cell. To this end we have synthesized a series of 3-deoxy-dioctanoyl phosphatidylinositol (3-deoxy-diC8PI) derivatives (Figure 1) with altered chirality of the inositol ring, and additional 5-deoxy-modification, or the addition of a phosphate group to the 5-hydroxyl group. The phosphate at C-5 was motivated by the possibility of producing an activator of PTEN since other groups have shown that phosphoinositides with a phosphate group at that position kinetically activate PTEN.22 This series of 3-deoxy-diC8PI molecules has been examined as substrates/inhibitors of PI3K, PI-specific phospholipase Cδ1, and PTEN (enzymes that could be inhibited by or degrade deoxy-diC8PI molecules in cells), and then screened as inhibitors of the human leukemia U937 cell line. Few of the 3-deoxy-PI compounds affected the kinase or phospholipase activities at low concentrations relative to substrate. However, interesting trends were observed for PTEN inhibition by d- and l- series of lipids that help delineate how this enzyme is likely to bind substrate molecules. Of all the compounds examined, only d-3-deoxy-diC8PI was cytotoxic to U937 cells with an IC50 of 40 μM, well below the CMC of 0.4 mM, and at a concentration where it had no effect on the recombinant enzymes examined. This very specific cytotoxicity profile for U937 cells is discussed in terms of the proposed target for this type of molecule.

Figure 1.

Structures of 3-deoxy-dioctanoylphosphatidylinositol (3-deoxy-diC8PI) compounds synthesized.

EXPERMENTAL SECTION

Deoxy-diC8PI lipids

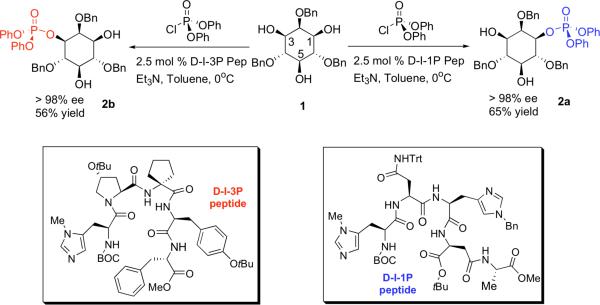

Peptide-catalyzed asymmetric phosphorylation (Scheme 1) has been used previously in the total synthesis of PI(3)P analogues.23 Combined with a monodebenzylation-Mitsunobu sequence, this methodology has also been applied in the syntheses of some deoxygenated PI analogues, in both enantiomeric series.24 The 3-deoxygenated analogue of PI(5)P and its enantiomer, 3-deoxydiC8PI(5)P and ent-3-deoxy-diC8PI(5)P, were prepared following the same strategy (Scheme 1) with both protected d- and l-3-deoxy-diC8PI, steps a through g in Scheme 2, as the starting points.

Scheme 1.

General scheme for the synthesis of different enantiomers of inositol phosphates for use in generating diC8PI derivatives.

Scheme 2.

Synthetic scheme for generation of d-3-deoxy-diC8PI(5)P and l-3-deoxy-diC8PI(5)P.

Protected d-3-deoxy-diC8 PI(5P)

To a stirred solution of the benzyl protected d-3-deoxy-diC8PI (0.020 g, 0.022 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (4.0 mL) was added dibenzyl diisopropyl-phosphoramidite (0.14 ml, 0.43 mmol) followed by 4,5-dicyanoimidazole (0.063 g, 0.54 mmol). The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 14 h and then cooled to 0 °C. 30% H2O2/H2O (2 ml) was added, and the reaction was stirred at 0 °C for another 1 h. The reaction was then quenched with saturated Na2SO3 solution (10 ml) and the mixture extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 30 ml). The organic layers were combined, dried over sodium sulfate, and then concentrated under reduced pressure to afford a clear oil. The crude product was purified using silica gel flash chromatography (using Silica Gel 60 Å (32-63 μm)) eluting with a gradient of 0–55% ethyl acetate/hexanes to afford pure product as a clear oil (0.022 g, 86% yield): 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz, referenced to tetramethylsilane at 0.00 ppm) δ 7.37–7.05 (m, 30H), 5.07 (m, 1H), 4.99–4.84 (m, 6H), 4.75 (m, 2H), 4.58–4.38 (m, 4H), 4.34–4.27 (m, 1H), 4.14–3.92 (m, 5H), 3.84 (m, 2H), 3.74 (dd, J = 5.6, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 2.19 (m, 5H), 1.62 (m, 1H), 1.54 (m, 4H), 1.27 (m, 16H), 0.87 (m 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz, referenced to tetramethylsilane at 0.00 ppm) δ 173.1, 173.0, 172.7, 138.4, 138.3, 138.2, 136.4, 136.3, 136.2, 136.1, 135.7, 135.6, 128.7, 128.6, 128.6, 128.6, 128.5, 128.5, 128.4, 128.4, 128.4, 128.2, 128.2, 128.0, 127.9, 127.8, 127.7, 127.7, 127.6, 127.6, 127.5, 127.4, 82.4, 80.4, 78.8, 74.9, 74.4, 72.6, 72.5, 72.3, 69.8, 69.7, 69.6, 69.6, 69.5, 69.4, 69.3, 61.8, 34.4, 34.3, 32.0, 30.3, 29.4, 29.3, 29.2, 25.2, 22.9, 14.4; 31P NMR (CDCl3, 121 MHz, relative to an 85% H3PO4 external standard) δ -0.28, -0.75, -0.85; IR (film, cm-1) 2927, 2855, 1742, 1455, 1270, 1213, 1155, 1012, 737, 697; TLC Rf 0.12 (50% ethyl acetate/hexanes); exact mass calcd. for [C67H84O15P2 + H]+ requires m/z 1191.5364, found 1191.5448 (ESI+). The optical rotation was recorded on a Rudolf Research Analytical Autopol IV Automatic polarimeter at the sodium D line (path length 50 mm): [α]D = -3.4 (4.0, CHCl3).

Protected l-3-deoxy-diC8PI(5)P

Synthesis and spectral data matched that for protected d-3-deoxydiC8PI(5)P above. [α]D = +3.1 (4.0, CHCl3).

d-3-Deoxy-diC8PI(5)P

To a stirred solution of benzyl protected d-3-deoxyl-diC8PI(5)P (0.020 g, 0.017 mmol) in t-BuOH/H2O (5:1, 3 ml) was added sodium ion-exchange resin (Chelex 100 sodium form, 50-100 dry mesh, washed with H2O) followed by Pd(OH)2/C (20 mg, washed with H2O). The reaction was then stirred at 1 atm of H2 for 32 h. The reaction mixture was filtered through Celite, and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure and lyophilized to afford a white solid (0.011 g, 91% yield). 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ 5.12 (m, 1H), 4.26 (m, 1H), 4.10 (m, 2H), 3.90 (m, 2H), 3.82 (m, 1H), 3.74 (m, 1H), 3.63 (m, 2H), 2.22 (m, 4H), 1.93 (m, 1H), 1.42 (m, 5H), 1.11 (m, 16H), 0.68 (m, 6H); 31P NMR (D2O, 121 MHz) δ 4.3, 0.5; exact mass calcd. for [C25H48O15P2 – H] – requires m/z 649.2390, found 649.2360 (ESI–); [α]D = +3.4 (1.0, H2O at pH = 9).

l-3-Deoxy-diC8PI(5)P

Synthesis and spectral data matched that for 3-deoxy-diC8PI(5)P above. [α]D = -5.2 (1.0, H2O at pH = 9).

All the purified lipids were treated with Chelex to remove contaminating paramagnetic ions (introduced via the Pd catalyst used in generating the final product). Concentrations of stock solutions were measured by 31P NMR (202.3 MHz) spectroscopy by comparing phosphorus peak integration (in the absence of 1H decoupling) with a standard inorganic phosphate peak.

31P NMR characterization of phospholipids

Most 31P NMR spectra (202.3 MHz) were obtained on a Varian INOVA 500 spectrometer. Variation of the 31P NMR linewidth for the synthetic PI as a function of lipid concentration (0.25 to 4 mM) was used to estimate the CMC values for several of these molecules in 50% D2O containing 100mM Tris HCl, pH 8.0, with 2 mM EDTA. In this concentration range the 31P linewidth of most of these compounds typically decreased 3-4 Hz to a constant value when only monomers were present. The CMC was estimated from a plot of the linewidth versus reciprocal PI concentration as the intersection of the two lines (negative slope for the micelle/monomer combination and zero slope for only monomers). Assays of recombinant enzyme activities were also done by 31P NMR on the Varian INOVA 500 (details below for each enzyme).

High resolution 31P NMR field cycling at magnetic fields from 0.004 to 11.74 Tesla (T) was carried out using a home-built shuttling system on a Varian UnityPLUS 500 spectrometer.25, 26 This technique was used to characterize two deoxy-diC8PI micelles and to explore if 0.5 mM d-diC8PI(3)P had detectable micelles when dispersed in the PTEN assay buffer. The sample, sealed in a standard 10 mm tube, was pneumatically shuttled to a higher position within, or just above, the magnet, where the magnetic field is between 0.06 and 11.7 T. Lower fields (down to 0.004 T for these samples) were accessible by shuttling to a region outside the magnet in the middle of a small Helmholtz coil located just above the top of the superconducting magnet. The spin-lattice relaxation rate, R1, at each field strength was measured using 6-8 programmed delay times.

Recombinant enzymes

Recombinant p110α/p85α PI-3-kinase was purchased from Upstate. A chimeric rat PLC with the catalytic domain of phospholipase Cδ1 and the N-terminal PH domain of phospholipase Cβ1 was the gift of Dr. Suzanne Scarlata, University of New York at Stony Brook. Recombinant Listeria monocytogenes phosphatidylinositol-specific PLC without its signal sequence27, 28 was expressed and purified using the IMPACT-CN expression system from New England Biolabs. The construction of pET28a PTEN has been described previously29; E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells were used as the host for protein expression. PTEN protein was purified from the bacterial extracts by using a Qiagen Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose column according to manufacturer protocol. Fractions of pure PTEN protein as judged on SDS-PAGE were combined and dialyzed against 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. Protein concentration was determined by Lowry assay.30

PI3K assay

PI3K (2 μg) was added to a reaction mix (400 μl) containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1 mg/ml BSA (Sigma), 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP, 1 mM d-diC8PI and 0 to 3 mM of the 3-deoxy-diC8PI analogues. The reaction was incubated at 22°C for 3 h and stopped by the addition of 10 mM EDTA. The phosphorylation of PI and PI analogues was monitored by 31P NMR spectroscopy using the phosphodiester resonance (δP = 0.23 ppm at pH 7.5) as the standard for integration of the PI3K phosphomonoester product. The acquisition conditions followed what has been previously used for PLC assays.31, 32 The amount of product produced was quantified by comparing the phosphomonoester resonance for d-diC8PI(3)P to the phosphodiester peak in the absence of 1H decoupling.

PLC assay

PLC activities toward diC8PI and the 3-deoxy-diC8PI analogues were measured by 31P NMR spectroscopy after incubation for fixed time points as described for other PI-specific PLC enzymes.31, 33 The assay buffer for PLCδ1 was 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.5; incubation was at 28°C. For the recombinant L. monocytogenes PLC, the assay buffer was 50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5 mg/ml BSA, pH 7.0, and incubation at 25°C. Enzyme (6.9 to 27.6 μg of PLCδ1 or 0.04 to 176 μg of L. monocytogenes PLC) was added to each 200 μl sample and incubation time was chosen so that less than 20% PI cleavage occurred. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 200 μl CHCl3 to the sample. Both cIP and I-1-P content in the aqueous phase were quantified in the 31P NMR spectrum using added glucose-6-phosphate as an internal standard.

PTEN assay

Phosphatase assays were carried out in 50 μl assay buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, and 10 mM DTT). The phosphatase reaction was initiated by adding ~25 μg of purified PTEN (10 μM) and quenched by adding the malachite green reagent containing 1 M HCl after a 20 min incubation at 37°C.34 A comparison of observed A660 changes to those for standard Pi samples was used to calculate the reaction rate. In most assays, 0.5 mM d-diC8PI(3)P was used as substrate and various concentrations (0.05 to 2 mM) of synthetic short-chain PIs were added to test their effect on phosphatase activity. For estimation of the Km for d-diC8PI(3)P, assays were carried out in 100 μl aliquots containing six different concentrations (0.05 to 1.6 mM) of substrate. Most assays were done at least in duplicate.

U937 cell growth and incubation with PI analogues

The U937 human leukemic monocyte lymphoma cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). U937 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), 2-mercaptoethanol (50 μM), and glutamine (2 mM) at a cell density of 5 × 105 to 1 × 106 cells/ml (at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 95% humidity). Cells were cultured in the presence or absence of the short-chain diC8PI compounds at the indicated concentration. Cells were also incubated with 10 μM LY294002 and/or 20 nM wortmannin. At the appropriate time, 2 to 5 × 105 cells were collected by centrifugation at 400 × g for 8 min, washed in FACS buffer (1 × PBS containing 0.5% BSA and 0.01% sodium azide), and resuspended in FACS buffer containing 5 μg/ml propidium iodide. Samples were incubated on ice for 10 min then analyzed by flow cytometry using a BD FACSCanto flow cytometer with BD FACS Diva software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Preparation of cell extracts and western blot analysis

Cells were washed twice in PBS and then incubated for 20 min at ~108/ml in RIPA buffer containing 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM PMSF, protein inhibitor cocktail, 1 mM okadaic acid, 1 mM sodium fluoride and 10mM β-glycerophosphate, followed by 3 freeze/thaw cycles in dry ice. Lysates were centrifuged at 14,000 × g (15 min) to remove insoluble material and then protein (20 μg/lane) was separated by polyacrylamide-SDS gel electrophoresis and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked in TBS-T (20 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 137 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween-20) containing 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h and then incubated overnight (4°C) with primary Ab at 1 μg/ml in TBS-T. The membrane was washed several times in TBS-T, incubated with a 1:2500 dilution of anti-rabbit IgG-coupled horseradish peroxidase Ab (60 min) and developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL). Bands for the different phosphorylated proteins were quantified by densitometric analysis, using the band corresponding to an extract from cells incubated with l-3-deoxy-diC8PI as a control since this compound had no effects on the U937 cells.

RESULTS

Characterization of diC8PI compounds

Three target enzymes that might be inhibited by (PI3K and PTEN) or degrade (PLC) 3-deoxy-PI molecules are soluble enzymes whose natural substrates are membrane constituents. However, in detailed kinetic studies with synthetic short-chain phospholipid substrates, these types of enzymes typically display a preference for molecules aggregated into a micelle compared to monomers in solution, a phenomenon termed ‘interfacial activation.’ Both phospholipase C and PI3K exhibit this enhanced activity with interfacial substrates / inhibitors.35, 36 Since the 3-deoxy-diC8PI molecules, unlike the longer acyl chain synthetic 3-deoxy-PI molecules examined previously,7, 14 can exist as both monomers and micelles in solution, we require information on the physical state of the short chain PI analogues, notably their CMC as well as roughly what size micelles they form. This is also critical information for determining the distribution of the 3-deoxy-diC8PI species in cells at concentrations where they may cause cell death. The critical micelle concentration (CMC) describes the concentration above which micelles form. All the dioctanoyl-PI derivatives used in this work have CMC values in 100 mM Tris HCl, pH 8, between 0.4 and 0.7 mM as measured by 31P linewidth changes as a function of lipid concentration (Table 1).

Table 1.

CMC values for dioctanoyl-PI compounds and IC50 for recombinant PTEN hydrolysis of d-3-deoxy-diC8PI(3)P.

| Phospholipids | CMC (mM)a | PTEN IC50 (mM)b |

|---|---|---|

| d-diC8PI | 0.5±0.1 | 0.43 |

| l-diC8PI | 0.5±0.1 | > 2.5 |

| d-diC8PI(3)P | 0.7±0.2 | |

| d-3-deoxy-diC8PI | 0.42±0.08 | 0.23 |

| l-3-deoxy-diC8PI | 0.40±0.07 | 1.5 |

| d-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI | 0.47±0.05 | 0.86 |

| l-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI | 0.47±0.07 | 0.38 |

| d-3-deoxy-diC8PI(5)P | 0.61±0.15 | 0.47 |

| l-3-deoxy-diC8PI(5)P | - | > 2.5 |

Determined by analysis of 31PNMR linewidth in D2O.

Determined with 0.5 mM d-3-deoxy-diC8PI(3)P as the substrate concentration.

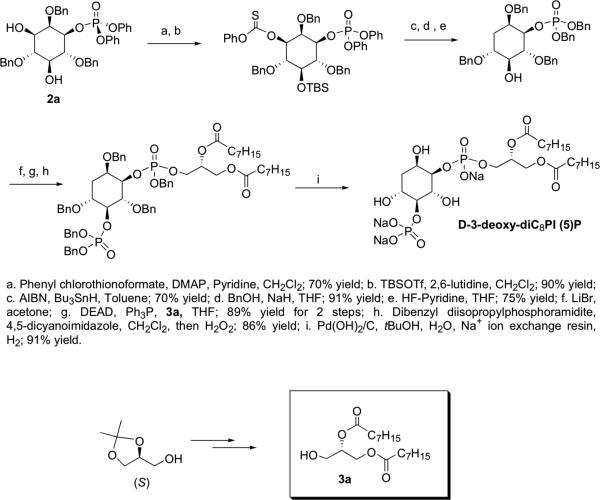

Two synthetic PIs (3 mM each), l-3-deoxy-diC8PI and l-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI, were examined at 3 mM by high resolution 31P field cycling to get a sense of the size and dynamics of these micelles. This is a novel technique that is very sensitive to the aggregation state of the micelles.25, 26 The l-isomers of deoxydiC8PIs were chosen since they had comparable CMC values to their enantiomers and more material was available. The field dependence of the 31P R1 from 0.1 up to 11.74 T for phospholipid aggregates can be analyzed in terms of a contribution from three terms: (i) dipolar relaxation associated with a ‘slow’ correlation time, τc, and a relaxation rate extrapolated to zero field, Rc(0) that is proportional to τc and inversely proportional to rPH6 (rPH is the effective distance of the phosphorus from the protons which relax this nucleus), (ii) chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) relaxation associated with the same slow correlation time, and (iii) CSA relaxation due to a faster motion(whose dipolar counterpart would be small and negligible in the analysis of these data). R1 is then the sum of those three terms.25 τc is determined directly while a correlation time for a faster motion (τhf) can be extracted from coefficients in the fits.25 In samples where phospholipid vesicles or large rod-shaped micelles form (e.g., diC7PC), there is a distinct rise in R1 detected at very low fields (<0.06 T).26 When well-separated from the nanosecond dispersion, a correlation time, τv, that may reflect the contribution of particle tumbling to relaxation can be extracted. It has been proposed that τv is equal to the rotational correlation time Dr/6 where Dr is the rotational diffusion constant of the individual lipid due to both diffusion of the entire aggregate, and translational diffusion of individual lipids relative to the aggregate.26

For micelles as opposed to vesicles, a detailed analysis is complicated by the fact that monomers and micelles coexist in fast exchange and that many micelles are usually rod-shaped rather than spherical. Nonetheless, the line shape of the R1 versus field profile can indicate that micelles form, and whether they are large (such that a low field rise in R1 is observed) or are small (in which case no low field rise is detected, but a minimum in rate at 1-2 T, suggesting a several ns correlation time). If the compound exists in solution as a monomer or very small aggregates (clusters of under 10 molecules) a single sub-nanosecond correlation time is likely to describe the behavior and R1 is invariant versus field below 2 T. This type of assay for micelles works well in complex buffer where other components can complicate other micelle detection methods (for instance impurities can skew surface tension measurements and dyes that fluoresce when partitioned into micelle environments can influence the measured CMC). The control for a monomeric phospholipid was 10 mM dibutyroylphosphatidylcholine (diC4PC) whose CMC is greater than 150 mM.37 The monomer lipid clearly showed a rise in R1 as the field was increased above 2 T (Figure 2A). This profile could be fit with a single correlation time of 0.75±0.08 ns. The maximum dipolar contribution, Rc(0), extrapolated from the low field constant contribution was 0.077±0.006 s-1. Both deoxy-diC8PI compounds showed higher R1 values and could not be well fit with a single correlation time, behavior indicative of aggregate formation (Figure 2A). With the simplistic but useful model-free analysis described previously,25 the 3-deoxy-diC8PI at this concentration was characterized by a 1.6±0.5 ns correlation time as well as a faster motion (τhf = 290±170 ps); the dideoxy-PI exhibited similar behavior with a 1.7±0.5 ns τc (τhf = 500±340 ps). Although the fast motions are not well defined, they must be included for reasonable fits to the data.

Figure 2.

31P field cycling profiles for deoxy-diC8PI compounds. Dependence of spin-lattice relaxation rate, R1, on magnetic field for 3 mM l-3-deoxy-diC8PI (●), 3 mM l-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI (○), and 10 mM diC4PC (Δ) in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, in the field range (A) 0.1 to 11.74 T, and (B) 0.03 to 1 T. (C) R1 for the phosphodiester 31P (●) and phosphate monoester (○) on the inositol C(3) of 0.5 mM d-diC8PI(3)P dissolved in PTEN assay buffer. The solid line indicates the relaxation profile for micellar l-3-deoxy-diC8PI while the dashed line indicates field dependence for the diC4PC monomer.

The ns τc clearly indicates that micelles are forming for these concentrations of the l-3-deoxy-diC8PI and the l-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI. A further enhanced relaxation rate below 0.1 T can be used to provide an average particle size from the high resolution field cycling. Below 0.1 T, R1 was invariant for 3-deoxydiC8PI but increased for the dideoxy-PI analog (Figure 2B). The correlation time for the 3,5-dideoxydiC8PI low field dispersion was 55±27 ns (this slower correlation time is defined as τv). If the micelles were spherical this would correspond to a radius of 38 Å. For comparison, diC7PC rod-shaped micelles exhibit a 200 to 350 ns τv (depending on concentration) for the low field dispersion.38 Clearly, the anionic deoxy-diC8PI micelles are considerably smaller. Since 3-deoxy-diC8PI did not exhibit a low field dispersion, its micelles must be even smaller in size and likely similar to those of dihexanoylphosphatidylcholine, which are 20-25 molecules per micelle and do not show a distinct low field dispersion.38 Thus, as a second hydroxyl group is removed from the inositol headgroup, the micelles formed are larger, but not as large as diC7PC micelles.

In the PI3K and PLC assays, d-diC8PI substrate was present at 1 or 2 mM, a concentration above the CMC. Adding more diC8PI analogs at 1 mM or higher should increase the micellar fraction in solution. Given the field cycling results on the two deoxy-PI compounds, all mixed micelles with diC8PI are likely to be relatively small (compared to short-chain PC micelles). This information on the physical state of the short chain PI analogues in assay buffers is important for understanding their interactions with enzymes that may show enhanced activity with interfacial substrates / inhibitors.

For PTEN assays, a concentration of 0.5 mM d-diC8PI(3)P was optimal for detection of inhibition by the different deoxy-PI compounds. This is in the vicinity of the CMC for this compound (the CMC values for the phosphorylated lipids, d-diC8PI(3)P which is the substrate for PTEN, and d-3-deoxy-diC8PI(5)P, were not very accurate since the changes in linewidth with concentration were small – less than 2 Hz). To assess whether micelles were present in assay mixtures of substrate in the absence of protein, we determined R1 for 0.5 mM d-diC8PI(3)P dispersed in the PTEN assay buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, and 10 mM DTT) at several field strengths (Figure 2C). This low concentration taxes the sensitivity of the field cycling system so that a complete field dependence profile could not be obtained. However, it does provide insight into the status of the d-diC8PI(3)P in solution under the conditions used in the PTEN assays. Both the phosphodiester phosphorus and the phosphate group on inositol C(3) of d-diC8PI(3)P exhibit significant CSA relaxation at higher fields and R1 decreases as the field decreases. The phosphodiester resonance has behavior intermediate between monomeric and aggregated phospholipids while the phosphomonoester has low field data that resembles a monomer. The higher limiting R1 value at low fields for the phosphodiester compared to the phosphomonoester could reflect the contribution of more protons to R1 of the –CH2O–P(O)2–OCH– compared to the –CHOPO3= group. Of more importance, a direct comparison of the d-diC8PI(3)P phosphodiester 31P profile to the phosphodiester in 3-deoxy-diC8PI strongly suggests that at 0.5 mM in the PTEN assay mixture there may be some small micelles as well as monomers of the substrate present. Since all diC8PI compounds have similar CMCs, the addition of inhibitors to a fixed substrate concentration (0.5 mM) is likely to increase the proportion of micelles. However, all inhibitors should have the same effect since their CMCs are essentially the same.

Effect of phospholipase C enzymes on 3-deoxy-diC8PI molecules

PI-specific PLC enzymes cleave PI molecules in two steps: (i) initial formation of diacylglycerol and the water-soluble product cyclic-inositol-1,2-phosphate, followed by (ii) hydrolysis of the cIP to inositol-1-phosphate.39-41 The initial 3-deoxy-PI studied as a cell growth inhibitor, d-3-deoxy-dipalmitoyl-PI, did not appear to be a substrate for PLC. However, that phospholipid has a high gel-to-liquid-crystalline phase transition temperature and may not have been presented in structures accessible to phospholipases in the in vitro assays. By using d-diC8PI micelles as the standard substrate, we can quantify the relative cleavage of the 3-deoxy-diC8PIs substrates as well as examine their ability to inhibit the enzyme, which reflects their ability to bind to PLC active sites. We examined the 3-deoxy-PI molecules as substrates and inhibitors of two different phosphatidylinositol-specific PLC enzymes – Ca2+-dependent mammalian PLCδ1 (this is a chimera of the –δ1 catalytic domain and the –β1 PH domain and was chosen because it has moderately high activity in vitro42) and a Ca2+-independent bacterial PLC. Mechanistically, PI cleavage occurs in a similar fashion in both types of enzymes except that an Arg replaces the active site Ca2+ in the bacterial enzyme.39, 40 As seen in Table 2, removal of the hydroxyl group at C3 generated a very poor substrate for the PLCδ enzyme with PI cleavage occurring at 0.5 to 1% that of diC8PI. However, in the context of a cell and over the time course of several days, these lipids are likely to be hydrolyzed by the endogenous PLC enzymes.

Table 2.

Recombinant PLCδ1 activity toward diC8PI and deoxy-diC8PI lipids.

| Substratea |

Inhibitor (mM)b |

|

Specific Activityc |

Relative Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d-diC8PI | 0.93 | 3.68 | 1.00 | |

| d-3-deoxy-diC8PI | 0.22 | 0.039 | 0.011 | |

| d-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI | 0.00 | 0.018 | 0.005 | |

| d-3-deoxy-diC8PI(5)P | 3.01 | 0.022 | 0.006 | |

| d-diC8PI | d-3-deoxy-diC8PI (2) | 1.99 | 3.01 | 0.82 |

| d-diC8PI | d-3-deoxy-diC8PI5P (6) | 1.29 | 4.81 | 1.31 |

| d-diC8PI | d-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI (2) | 1.77 | 3.25 | 0.88 |

| d-diC8PI | d-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI (6) | 0.99 | 3.93 | 1.07 |

| d-diC8PI | l-diC8PI (2) | 1.02 | 3.08 | 0.84 |

Substrates present at 2 mM.

The value in parentheses represents the concentration of inhibitor used in these assays.

Errors in specific activity typically <20%.

These compounds were also not very good inhibitors of the PLCδ. The ratio of cIP to the final water-soluble product I-1-P reflects how well the intermediate is bound to the enzyme. A tighter binding cIP generated in situ translates to a lower ratio of cIP/I-1-P.33, 33, 43 As hydroxyl groups are removed from the inositol ring, the intermediate cIP analogue becomes more hydrophobic and its release is slow compared to attack by water and production of I-1-P (Table 2). With d-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI, no cIP was observed suggesting that the enzyme must hold the cyclic intermediate sufficiently long that it is always hydrolyzed (but very slowly). Addition of a phosphate to C(5) to produce d-3-deoxy-diC8PI(5)P did not generate a better substrate but it did bias the enzyme so that now cIP was the dominant product (compared to hydrolysis of d-3-deoxy-diC8PI). This is an interesting contrast to how the enzyme hydrolyzed phosphorylated glycerol-phosphoinositols,33 where a phosphorylated substrate was more efficiently hydrolyzed and I-1-P became the major product. It strongly indicates that the 3-hydroxy group of the inositol ring must make important hydrogen bond contacts with the enzyme that stabilize binding of PI analogues to the protein but not in an optimal configuration for PI cleavage.

Mammalian PLC enzymes have multiple domains that could complicate / mask effects of the deoxy-diC8PI compounds. Therefore, for comparison we also examined the effect of these compounds on the PLC from L. monocytogenes. This bacterial PLC is essentially the catalytic domain of the mammalian enzymes and serves to assess the effects of the deoxy-PI compounds on catalysis only. The 3-deoxy-diC8PI compounds were also poor substrates and poor inhibitors for L. monocytogenes PLC (Table 3). The specific activities toward d-3-deoxy-diC8PI and d-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI were 1.3 and 0.037% that toward diC8PI, respectively. Addition of 2 to 6 mM deoxy-PI compounds had only minor effects on the activity of L. monocytogenes PLC toward 2 mM d-diC8PI. For all the deoxy- compounds, the decrease in specific activity was less than 10%, comparable to the effect of l-diC8PI. As with the mammalian enzyme, removal of the 3-hydroxyl group generates a compound that binds very poorly to PLC and does not compete well with substrate.

Table 3.

Recombinant L. monocytogenes PI-PLC activity toward D-diC8PI molecules and inhibition by deoxy-diC8PI lipids.

| Substratea |

Inhibitor (mM)b |

Specific Activityc (μmol min−1 mg−1) |

Relative Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| d-diC8PI | 489 | 1.00 | |

| d-3-deoxy-diC8PI | 6.44 | 0.013 | |

| d-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI | 0.18 | 3.7×10−4 | |

| d-diC8PI | d-3-deoxy-diC8PI (2) | 522 | 1.07 |

| d-diC8PI | d-3-deoxy-diC8PI(5)P (6) | 452 | 0.92 |

| d-diC8PI | d-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI (2) | 522 | 1.07 |

| d-diC8PI | d-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI (6) | 539 | 1.10 |

| d-diC8PI | l-diC8PI (2) | 441 | 0.90 |

Substrates present at 2 mM.

The value in parentheses represents the concentration of inhibitor used in these PI-PLC assays.

Errors in specific activity were ≤15%.

Effect of 3-deoxy-diC8PI molecules on PI3K activity

Removal of the 3-hydroxyl group from PI generates a molecule that should inhibit PI3K phosphorylation of d-diC8PI. Previous work7 has suggested that the 3-deoxy-PI species are not very potent inhibitors of PI3K, although this can be misleading if substrate and inhibitor have different chain lengths or solubilities. In an attempt to keep substrate and inhibitors in the same physical state we investigated the activity of the p110α/p85α complex towards 1 mM d-diC8PI in the absence and presence of 3 mM 3-deoxy-diC8PI analogs (the high deoxy-PI concentration was chosen to maximize observation of any inhibition). Since PI3K has been shown to work in a scooting mode with PI dispersed in vesicles,36 the concentrations of PIs were chosen so that substrate (and in most cases inhibitor) was micellar. In fact, kinetics attempts with 0.3 or 0.5 mM substrate and comparable concentrations of the deoxy-PI molecules exhibited either no effect or an increase in activity (and a high degree of error) likely due to formation of micelles and better presentation of substrate. As shown in Table 4, both d- and l-3-deoxy-diC8PI inhibited the phosphorylation of diC8PI; removing a second hydroxyl group (data not shown) or adding a phosphate to the 5-hydroxyl group reduced the potency of these compounds as inhibitors so that very little inhibition was observed under these conditions of excess inhibitor. For comparison, we also examined the inhibitory effect of l-diC8PI on p110α/p85α activity toward d-diC8PI. The substrate enantiomer had no effect on d-diC8PI phosphorylation, indicating that the observed inhibition for the 3-deoxy-diC8PI molecules is not just surface dilution inhibition but represents a real binding effect of the enzyme with PI3K. The replacement of the 3-hydroxyl of the inositol ring of diC8PI with hydrogen (deoxygenation) not only improved the binding of 3-deoxy-diC8PI compounds to PI3K (compared to diC8PI) but also eliminated the inositol ring stereoisomer selectivity for ligand binding. A phosphorylated 3-deoxy-diC8PI (d-3-diC8PI(5)P) was also examined for inhibition of diC8PI phosphorylation by PI3K. Enzyme activity decreased only 20% with an excess of d-3-diC8PI(5)P. These in vitro assays suggest that the 3-deoxydiC8PI molecules, especially when monomeric, are unlikely to have a large effect on PI3K in vivo. They also suggest that if PI3K is involved in vivo, both d- and l-3-deoxy-diC8PI should have similar effects as growth inhibitors.

Table 4.

Recombinant PI3K (P110α/P85α) activity toward d-diC8PI (1 mM) and inhibition by l- and d- deoxy-diC8PI lipids.a

| Inhibitor |

(mM) |

Specific Activity b (μmol min-1 mg-1) |

Relative Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| – | 0.60 | 1.00 | |

| d-3-deoxy-diC8PI | 3 | 0.09 | 0.15 |

| d-3-deoxy-diC8PI(5)P | 3 | 0.49 | 0.81 |

| l-diC8PI | 3 | 0.60 | 1.00 |

| l-3-deoxy-diC8PI | 3 | 0.11 | 0.18 |

Assay conditions included 1 mM d-diC8PI and 2 mM ATP as substrates, 5 mM Mg2+, in 50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.5, with 3 mM of the deoxy-PI analogs.

For several of the samples run in duplicate, the error in determining the specific activity was <10%.

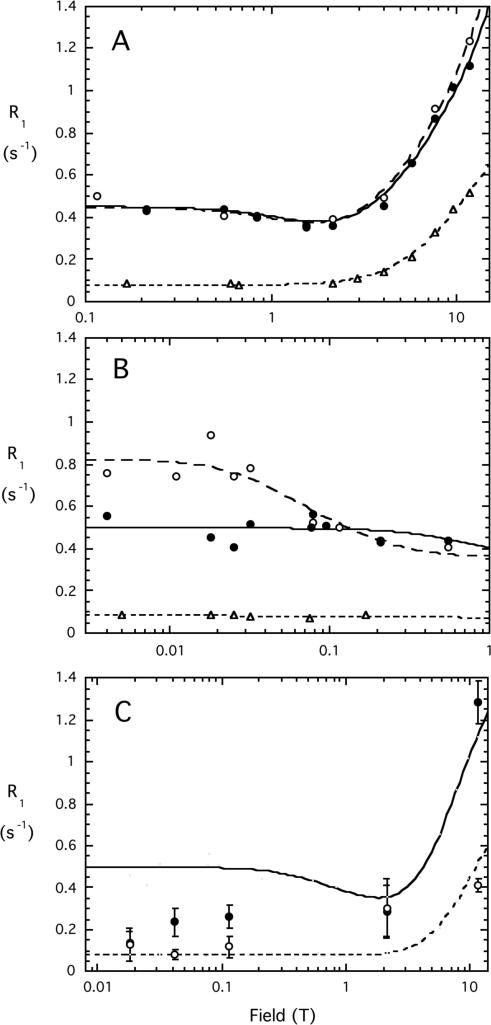

Effect of 3-deoxy-diC8PI molecules on PTEN activity

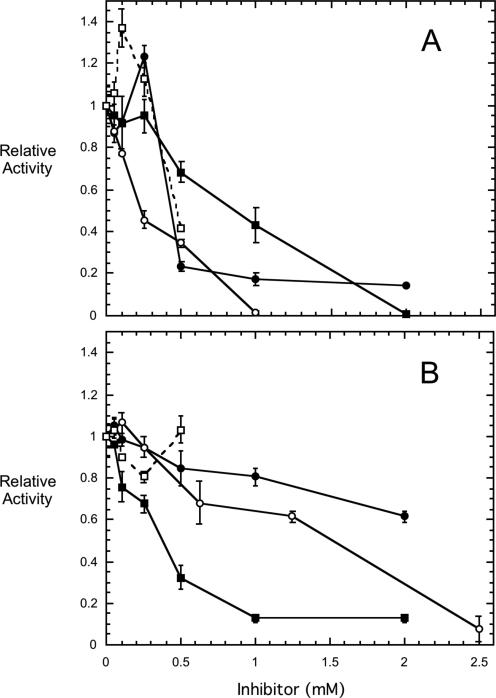

Although PTEN is often mutated in some tumor cells, in others it could be a potential target for inhibition by the short-chain 3-deoxy-diC8PI molecules. This would not be productive if the aim of the treatment is to induce cell death of the tumor cells. To check this, we examined all the different 3-deoxy-PI molecules as inhibitors of PTEN (Figure 3). The substrate in this case is d-diC8PI(3)P at 0.5 mM, a concentration in these assay mixtures where the there is a mixture of monomers and some small micelles. The dependence of specific activity on the concentration of this substrate exhibited an apparent Km of 0.20±0.07 mM and a Vmax of 14±1 nmol min-1 mg-1 at 37°C. The different 3-deoxy-PI compounds as well as diC8PI, from 0.05 up to 2.5 mM, were examined as inhibitors of PTEN (IC50 values in Table 1). At inhibitor concentrations >0.5 mM (compared to 0.5 mM substrate), all the synthetic PI molecules were inhibitory, although the l-phosphatidylinositols (Figure 3B) were usually poorer inhibitors than the d-inositol lipids (Figure 3A). The compound d-3-deoxy-diC8PI was the most potent inhibitor towards 0.5 mM substrate with an IC50 of 0.23 mM under these conditions and consistent with tighter binding than reflected in the substrate apparent Km. Two very interesting kinetic trends were observed: (i) as the 3- and 5-hydroxy groups were replaced with hydrogen, the l-diC8PI derivatives became more potent inhibitors with l-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI more inhibitory below 1 mM than its enantiomer, and (ii) at 0.1-0.3 mM two of the compounds, d-diC8PI and d-3-deoxy-diC8PI(5)P, activated PTEN 20-40% for d-diC8PI(3)P hydrolysis. The l-enantiomers of these compounds had no activating effect in this concentration range. Activation of PTEN by PI(4,5)P2 has been reported previously.22 In our system, where all PIs have similar CMC values, we can suggest that the non-substrate d-3-deoxy-diC8PI(5)P must be binding as a monomer in a stereospecific manner to PTEN to enhance its hydrolysis of diC8PI(3)P, since activation is seen at low total PI concentrations. Even if some substrate aggregation occurs, the other non-activating PI molecules are likely to have the same effects on the physical distribution of substrate between monomer and very small micelles. Since they do not activate PTEN, the effect must be due to a specific PTEN/ d-3-deoxydiC8PI(5)P interaction. However, extrapolating these results to the in vivo situation, we would predict that at 3-deoxy-PI concentrations <0.05 mM, there should be little inhibition of PTEN; any activation by diC8PI compounds is also likely to be small under these conditions.

Figure 3.

Effect of diC8PI derivatives on the activity of PTEN toward 0.5 mM d-diC8PI(3)P. In (A) are shown the effects of d- enantiomers and in (B) the effects of the corresponding l- enantiomers: diC8PI (●), 3-deoxy-diC8PI (○), 3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI (■), and 3-deoxy-diC8PI(5)P (□).

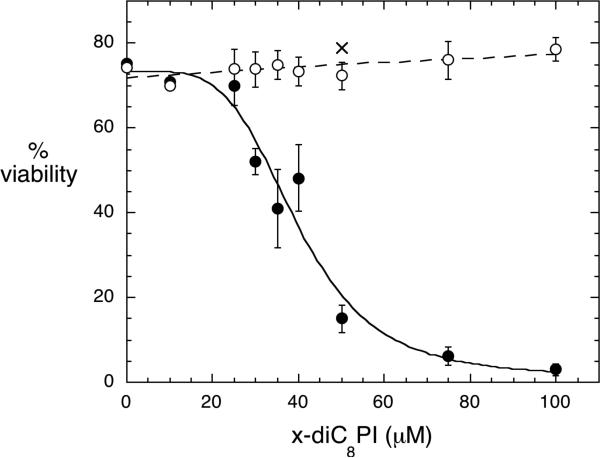

Effect of 3-deoxy-diC8PI compounds on the growth of the U937 human lymphoma cell line

The longer chain d-3-deoxy-PI analogs are thought to inhibit cell growth by competing with PI(3)P for binding to the Akt1 PH domain and reducing Akt1 translocation to the plasma membrane.7 The short-chain 3-deoxy-diC8PI compounds could affect cell survival in a similar fashion. The difference is that the short-chain PI analogs at low concentrations are likely to be monomeric in the cell as opposed to partitioning into membranes (expected for the long-chain PI analogs). There may also be specificity among the different deoxy-PI compounds that would shed light on key interactions of these modified PIs with diverse targets. To explore this, we incubated the human leukemic monocyte lymphoma cell line U937 with the compounds d-3-deoxy-diC8PI, l-3-deoxy-diC8PI, d-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI, and l-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI at various concentrations, and assessed the viability of the cells at different time points. Of all the compounds tested, only d-3-deoxy-diC8PI had any significant effect on cell viability, with an IC50 of 40 μM (Figure 4). The other compounds had no measurable effect on viability at concentrations up to 200 μM.

Figure 4.

Viability of U937 cells after incubation with different concentrations of 3-deoxy-diC8PI compounds for 24 h: d-3-deoxy-diC8PI (●), l-3-deoxy-diC8PI (○), and d-3-diC8PI(5)P (X).

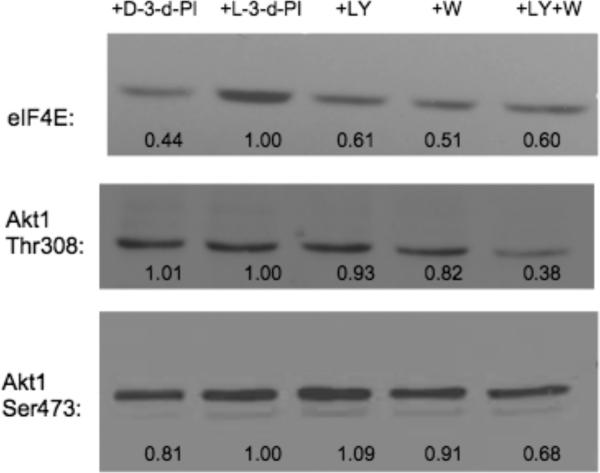

To determine if the 3-deoxy-diC8PI compounds inhibited endogenous signaling via the PI3K pathway, we assessed phosphorylation of Akt1, a downstream target of PI3K, and compared the effects of the short-chain PI compounds (50 μM) to the effects of LY294002 (10 μM) and wortmannin (20 nM), known inhibitors of signaling via the PI3K/Akt pathway (Figure 5). Since l-3-deoxy-PI had no effect on cell growth, the intensity of the band from cells incubated with that compound was used as a phosphorylation control. Phosphorylation of the transcriptional initiation factor eIF4E was clearly reduced after incubation of the cells with d-3-deoxy-diC8PI for 24 h. However, reduction in Akt phosphorylation appeared to show interesting specificity. The phosphorylation of Thr308 did not appear to be affected by d-3-deoxy-diC8PI, while LY294002 and wortmannin did lead to some reduced phosphorylation in the same time period (and the combination of the two was extremely effective). In contrast, Ser473 phosphorylation was reduced (more than with the two other known inhibitors of the PI3K/Akt pathway at this time point) when the cells were incubated with d-3-deoxy-diC8PI. In previous work with d-3-deoxy-PI molecules,7 Akt Ser473 phosphorylation was significantly reduced (to about 65% of the maximum phosphorylation for the d-3-deoxy-diC16PI). Here we show that the more soluble short-chain d-3-deoxy-diC8PI can also reduce Akt1 phosphorylation on Ser473. Whether it does so by preventing Akt translocation or by altering the interaction of the protein with the membrane remains to be seen. That this soluble, specific enantiomer, and not further deoxygenated compounds, is cytotoxic and affects Akt1 phosphorylation is an exciting observation.

Figure 5.

Western blots used to monitor phosphorylation of Akt1 (at both Ser473 and Thr308) as well as eIF4E (Ser209) after 24 h incubation with 50 μM d-3-deoxy-diC8PI (d-3-d-PI), 50 μM l-3-deoxydiC8PI (l-3-d-PI), 10 μM LY 294002 (LY) or 20 nM wortmannin (WM) or a combination LY 294002 and wortmannin (LY+W). The numbers under each lane represent the fractional phosphorylation in the presence of the indicated compound compared to phosphorylation in the presence of l-3-deoxy-diC8PI, which has no effect on the cells.

DISCUSSION

Compounds based on d-3-deoxy-PI have been examined as cell growth inhibitors for a variety of cancer cells.12-14 The first analogue examined, d-3-deoxy-diC16PI, inhibited the growth of NIH3T3 mouse fibroblasts with an IC50 of 17.6 μM.7 Modifications of the 3-deoxy-PI to increase potency included replacing acyl chains with ether linked chains, and shortening the chain attached to the glycerol sn-2 position.14 The ether bonds should make the 3-deoxy-PI compounds stable to PLA2 type activities, although most of the mammalian PLA2 enzymes are not selective for PI headgroups. Work by Tabellini et al.15 showed that at 5 μM the ether-linked 3-deoxy-PI analogues (2-substituted, 3-deoxy-PIs) had a small effect by themselves but enhanced induction of apoptosis when administered with either etoposide or cytarabine. At this concentration they were not toxic to human umbilical cells, although doubling the concentration of the deoxy-PI caused a pronounced increased in cell apoptosis. Shortening the sn-2 chain length may make also a more significant contribution to molecule potency. This creates a more lyso-like phospholipid that has a higher solution concentration than the diacyl long chain lipids. However, other structural aspects of 3-deoxyl-PI that make it cytotoxic have not been studied.

In this work we have used synthetic diC8PI compounds, both as substrates for different target enzymes and to screen for 3-deoxy-PI inhibition in vitro. Knowing the CMC values for these lipids allows us to carefully interpret in vitro assays. In the case of PI3K and PLC enzymes, the assays use mixed micelles to assess analog inhibitory potency. For PTEN, assays have a mix of monomers and some small micelles. We have examined how inositol stereochemistry as well as specific hydroxyl groups at C(3) and C(5) on the ring contribute to the cytotoxicity of this class of phosphatidylinositols. The 3-deoxy-diC8PI molecules are poor inhibitors of PI3K and only moderate inhibitors of PTEN. They are neither good substrates nor inhibitors of PI-PLC enzymes, strongly indicating that these enzymes are not the in vivo target(s). The compound d-3-deoxy-diC8PI, and only that PI in this series, is cytotoxic to U937 cell. These leukemic cells provide a good system to evaluate effectiveness of the diverse 3-deoxy-PIs because they have an activated PI3K/Akt pathway. Since neither the enantiomer of d-3-deoxy-diC8PI nor d-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI were cytotoxic, the in vivo target must bind d-3-deoxy-diC8PI in a very specific way.

The mechanism of action of the 3-deoxy-PIs has been proposed to be the binding of this lipid to the PH domain of Akt1.7 This binding is then supposed to prevent targeting of Akt1 to the plasma membrane for phosphorylation and subsequent activation. Indeed, studies have shown that this molecule inhibits growth of cell lines where Akt1 is the major isoform of this protein kinase.12-14 Akt1 is phosphorylated on Ser473 and Thr308; treatment of cells with the 3-deoxy-diC16PI and the ether-linked long chain PI analogue DPIEL showed that phosphorylation of the Ser sites was reduced.7 Other lipid-based antitumor compounds have been shown to alter Thr308 phosphorylation,15 so it is not clear whether one or both phosphorylation sites are critical for Akt1 activation. In fact, one can ask if the reduced phosphorylation of Akt1 really represents the mechanism by which the 3-deoxy-PI molecules inhibit cell growth. All the previously examined modified phospholipids are relatively hydrophobic and could presumably be integrated into different intracellular membranes, attracting the Akt1 to a membrane devoid of its activating kinase. By using short-chain synthetic 3-deoxy-PI compounds, which should be monomeric in the cell at concentrations less than 0.1 mM, and showing that only d-3-deoxy-diC8PI is inhibitory in vivo, we provide data indicating that a very specific interaction of the 3-deoxy-PI with its target occurs. Inositol ring attachment to the glycerol backbone (only the d- compound is inhibitory) is critical as is the C(5) hydroxyl group. The observation that an Akt1 downstream target (eIF4E) exhibited reduced phosphorylation, strongly points to Akt1 as the likely in vivo target of d-3-deoxy-diC8PI. Furthermore, since Akt1 phosphorylation on Ser473 was reduced while that on Thr308 was unaffected, we might propose that this lipid analog has its primary effect in modulating Ser phosphorylation. Interestingly, recent work also suggests that phosphatidylinositol ether lipid analogues activate the proapoptotic stress kinase p38α that is a subgroup of the MAPK family and activated by phosphorylation by MAPKKs.16 This particular interaction could also contribute to the cytotoxicity of 3-deoxy-PIs. With the in vivo specificity profile in hand for the soluble, synthetic 3-deoxy-diC8PI analogs, one might further explore that kinase in vitro to assess direct effects of the 3-deoxy-PIs.

Although there is no direct evidence for an Akt1 PH domain complex with 3-deoxy-PI, there is a crystal structure of the PH domain with a polyphosphorylated inositol bound. The crystal structure of the Akt PH domain with I(1,3,4,5)P4 bound44, 45 shows strong interactions of the protein with the 3- and 4-phosphate groups (not the 5-phosphate which was poised towards solvent and not tightly held). Given the importance of the phosphate monoester interactions in this structure, it might be surprising that the 3-deoxy-PIs bind at all to the PH domain. The interaction of the Akt1 PH domain with the inositol ring of the 3-deoxy compounds is likely to be quite different than its interaction with I(1,3,4,5)P4. Indeed, previous modeling studies of a 3-deoxy-PI binding to the Akt1 PH domain showed strong H-bonds of the inositol 4- and 5-hydroxyl groups with the protein.7 Consistent with the modeling, we have shown that, while d-3-deoxy-diC8PI inhibits U937 cell growth, d-3,5-dideoxy-diC8PI is no longer cytotoxic. Given the very cationic nature of the Akt1 PH domain binding site, one might expect a phosphate at C(5) in d-3-deoxy-diC8PI to enhance analogue binding. However, we observed no growth inhibition by d-3-deoxydiC8PI(5)P. It is possible that such a compound was not taken up by the U937 cells, since intracellular phosphatases would have been expected to remove the phosphate and generate d-3-deoxy-diC8PI, which is inhibitory. d-3-Deoxy-diC8PI, unlike the longer chain length analogues studied previously, will be monomeric in the tumor cells at the concentrations where it was found to be cytotoxic. This observation decouples membrane partitioning of the modified PI from specific target / 3-deoxy-PI interactions. The increased solubility without a decrease in tumor potency (compared to the ester-linked long-chain 3-deoxy-PI) may also be important for reducing toxic effect in normal cells. Tantalizing to this possibility, in preliminary experiments where 0.2 mM d-3-deoxy-diC8PI was incubated with primary B cells (which have all three Akt forms), there was little loss of cell viability (M. Pu, D. Blair, and T. Chiles, unpublished results). Clearly, the area is ripe for further investigation with well-defined soluble 3-deoxy-PI molecules.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Suzanne Scarlata for the chimeric PLCδ1 and Dr. Wonhwa Cho for the plasmid containing PTEN. This work was supported by NIH grants GM60418 (M.F.R.), GM68649 (S.J.M.), GM077974 (A.G.R.), and AI49994 (T.C.C.) and N.S.F. MCB-0517381 (M.F.R.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seufferlein T. Int. J. Gastronint. Cancer. 2002;31:15–21. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:31:1-3:15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosh PM, Malik S, Bedolla R, Kreisberg JL. Curr. Drug Metab. 2003;4:487–496. doi: 10.2174/1389200033489226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnett S, Bilodeau M, Lindsley C. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2005;5:109–125. doi: 10.2174/1568026053507714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kandel ES, Hay N. Exp. Cell Res. 1999;253:210–229. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiao L, Nan F, Kunkel M, Gallegos A, Powis G, Kozikowski AP. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:3303–3206. doi: 10.1021/jm980254j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meuillet EJ, Mahadevan D, Vankayalapati H, Berggren M, Williams R, Coon A, Kozikowski AP, Powis G. Molec. Cancer Therap. 2003;2:389–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim D, Dan HC, Park S, Yang L, Liu Q, Kaneko S, Ning J, He L, Yang H, Sun M, Nicosia SV, Cheng JQ. Front. Biosci. 2005;10:975–987. doi: 10.2741/1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, Yen C, Liaw D, Podsypanima K, Bose S, Wang SI, Puc J, Millaresis C, Rodgers L, McComble R. Science. 1997;275:1943–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steck PA, Pershouse MA, Jasser SA, Ung WK, Lin H, Ligon A. Nat. Genet. 1997;15:356–362. doi: 10.1038/ng0497-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gills JJ, Dennis PA. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2004;13:787–797. doi: 10.1517/13543784.13.7.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozikowski AP, Kiddle JJ, Frew T, Berggren M, Powis G. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:1053–1056. doi: 10.1021/jm00007a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kozikowski AP, Sun H, Brognard J, Dennis PA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1144–1145. doi: 10.1021/ja0285159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andresen TL, Skytte DM, Madsen R. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004;2:2951–2957. doi: 10.1039/B411021H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tabellini G, Tazzari PL, Bortul R, Billi AM, Cocco L, Martelli AM. Br. J. Haemat. 2004;126:574–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gills JJ, Holbeck S, Hollingshead M, Hewitt SM, Kozikowski AP, Dennis PA. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006;2006;5:713–722. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruiter GA, Zerp SF, Bartelink H, van Bitterswijk WJ, Verheij M. Anticancer Drugs. 2003;14:167–173. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200302000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kondapaka SB, Singh SS, Dasmahapatra GP, Sausville EA, Roy KK. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2003;2:1093–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castillo SS, Brognard J, Petukhov PA, Zhang C, Tsurutani J, Granville CA, Li M, Jung M, West KA, Gills JJ, Kozikowski AP, Dennis PA. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2782–2792. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemieux RU. Acc. Chem. Res. 1996;29:373–380. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tor Y. ChemBioChem. 2003;4:998–1007. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell RB, Liu F, Ross AH. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:33617–33620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300296200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sculimbrene BR, Xu Y, Miller SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13182–13183. doi: 10.1021/ja0466098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu Y, Sculimbrene BR, Miller SJ. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:4919–4928. doi: 10.1021/jo060702s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts MF, Redfield AG. J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13765–13777. doi: 10.1021/ja046658k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts MF, Redfield AG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:17066–17071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407565101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldfine H, Kolb C. Infect. Immun. 1992;60:4059–4067. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4059-4067.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan M, Zaikova TO, Keana JF, Goldfine H, Griffith OH. Biophys. Chem. 2002;101-102:347–358. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(02)00158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Das S, Dixon JE, Cho W. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:7491–7496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr. AL, Randall RJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou C, Wu Y, Roberts MF. Biochemistry. 1997;36:347–355. doi: 10.1021/bi960601w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng J, Bradley WD, Roberts MF. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:24651–24657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Y, Perisic O, Williams RL, Katan M, Roberts MF. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11223–11233. doi: 10.1021/bi971039s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Itaya K, Ui M. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1966;14:361–366. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(66)90114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis KA, Garigapati VR, Zhou C, Roberts MF. Biochemistry. 1993;32:8836–8841. doi: 10.1021/bi00085a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barnett SF, Ledder LM, Stirdivant SM, Ahern J, Conroy RR, Heimbrook DC. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14254–14262. doi: 10.1021/bi00043a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bian J, Roberts MF. J. Coll. & Int. Sci. 1992;153:420–428. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi X, Shao C, Zhang X, Zambonelli C, Redfield AG, Head JF, Seaton BA, Roberts MF. 2007. submitted for publication.

- 39.Griffith OH, Ryan M. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1441:237–254. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hondal RJ, Zhao Z, Kravchuk AV, Liao H, Riddle SR, Yue X, Bruzik KS, Tsai MD. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4568–4580. doi: 10.1021/bi972646i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heinz DW, Essen LO, Williams RL. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;275:635–650. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feng J, Roberts MF, Drin G, Scarlata S. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2577–2584. doi: 10.1021/bi0482607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Y, Bruzik KS, Ananthanarayanan B, Cho W. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003;11:2471–2475. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(03)00150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomas CC, Deak M, Alessi DR, van Aalten DMF. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:1256–1262. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00972-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar CC, Madison V. Oncogene. 2005;24:7493–7501. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]