Abstract

Monodisperse magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) were synthesized by thermal decomposition of iron-oleate and functionalized with silanes bearing various functional groups such as amino group (NH2), short-chain poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), and carboxylic group (COOH). Then, silanes-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles (silanes-MNPs) were incubated in cell culture medium plus fetal calf serum to investigate the effects of proteins from culture medium on surface property of MNPs. Zeta potential measurements showed that although surface charges of silanes-MNPs were different, they exhibited negative charges at neutral pH and approximate isoelectric points after they were incubated in cell culture medium. The reason was that silanes-MNPs could easily adsorb proteins from culture medium via non-covalent binding, resulting in the formation of protein-silanes-MNPs conjugates. Moreover, silanes-MNPs with various functional groups had different adsorption capacity to proteins, as confirmed by Coomassie blue fast staining method. The in vitro cell experiments showed that protein-silanes-MNPs had higher cellular uptake by cancer cells than silanes-MNPs.

Keywords: Magnetic nanoparticles, Culture medium, Protein, Surface property, Cellular uptake

Introduction

Magnetic nanoparticles have been identified as potential candidates for biological applications including magnetic separation [1], magnetic resonance image (MRI) [2-4], magnetic hyperthermia [5,6], and so on. As a result of this drive to integrate MNPs into biological systems, a lot of research has focused on the interactions between MNPs and cancer cells. In terms of specifically biological applications, MNPs are always functionalized with interesting molecules such as PEG [7-10] and folic acid [11,12], suggesting that surface chemistry of MNPs play an important role in relative topics. It is well known that the in vitro investigations on the interactions between MNPs and cancer are usually carried out in various cell culture mediums such as DMEM and RPMI-1640. At the same time, cell culture medium is a complex system and contains a lot of proteins, which can be adsorbed by MNPs. Thereby, it could be predicted that MNPs may exhibit novel surface properties due to the adsorption of proteins once MNPs are dispersed in cell culture medium. The change of surface properties can inevitably influence the interactions between MNPs and cancer cells because the surface is in direct contact with cells. Unfortunately, it had always been ignored until some research reported recently. Chithrani et al. [13] found that Au nanoparticles could only be well dispersed in DEME cell culture medium plus 10% serum. Similarly, Casey et al. [14] reported that single-walled carbon nanotubes could be well dispersed in medium (F12 K) with 5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), resulting from interaction of both components of F12 K and FBS with carbon nanotubes likely through a physisorption. Zhu et al. [15] further demonstrated that the formation of peptone-MWNTs conjugates by non-covalent binding due to the adsorption of peptone in proteose peptone yeast extract medium onto the surface of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWNTs) stimulated growth of cells. In our previous study, we reported that fetal calf serum in RPMI-1640 cell culture medium played a great role in the stability of 2, 3-dimercaptosuccinnic acid (DMSA)-coated MNPs under biological conditions, as well as their surface property and intracellular uptake [16], which is attributed to the adsorption of fetal calf serum onto the surface of MNPs.

In this study, monodisperse MNPs (Fe3O4) were synthesized by iron-oleate thermal decomposition method and functionalized with silanes bearing different functional groups such as NH2, short-chain PEG, and COOH. Despite the distinct surface properties, all of these silanes-MNPs exhibited negative surface charges at neutral pH and approximate isoelectric point (IEP) when incubating in cell culture medium (RPMI-1640 plus 10% fetal calf serum (FCS)). This phenomenon was attributed to the adsorption of proteins from fetal calf serum onto the surface of silanes-MNPs and the formation of protein-silanes-MNPs conjugates. Moreover, the different adsorption capacities of silanes-MNPs to proteins were determined by Coomassie blue fast staining method. The further in vitro experiment results proposed that the adsorbed proteins affected the interactions between silanes-MNPs and cancer cells, suggesting that the effects of proteins from culture medium on surface property of MNPs should be taken into account in relatively biological investigations.

Experimental Sections

Materials

1-octadecene was purchased from Alfa Aesar. 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane (NH2-silane),n-(trimethoxysilylpropyl)ethylene diamine triacetic acid (45% in water)(COOH-silane), and 2-[methoxy-(polyethyleneoxy)propyl]trimethoxysilane (PEG-silane) were obtained from ABCR gmbh. Coomassie blue (G-250) was purchased from Amerosco. The other chemicals were analytical reagents and purchased from Shanghai Chemical Reagent Corporation, China. All chemicals were used as received.

Synthesis of Monodisperse Fe3O4MNPs

The synthesis of monodisperse Fe3O4 MNPs was based on a previously reported study [17]. In brief, 1.08 g (4 mmol) of FeCl3 · 6H2O and 3.65 g (12 mmol) of sodium-oleate were dissolved in a mixture solvent containing 6 mL water, 8 mL ethanol, and 14 mL hexane. The resulting solution was stirred for 4 h at 70 °C. Then, the upper organic layer containing iron-oleate was washed three times with 3 mL water in a separatory funnel. After the water and hexane were evaporated off under vacuum, solid iron–oleate was collected. The obtained 2.8 g (3 mmol) iron–oleate and 0.42 g (1.5 mmol) of oleic acid thus obtained were dissolved in 15 g (50 mmol) 1-octadecene. The mixture was heated to 320 °C at a constant heating rate of 3.3 °C/min and maintained at that temperature for 30 min. Later, the resulting solution was cooled, precipitated by addition of excess ethanol. Then, the precipitate containing MNPs was washed 4–5 times with a mixture of hexane and acetone. Finally, MNPs were dispersed in hexane to obtain a black solution.

Surface Functionalization of MNPs with Silanes

In a glass container under ambient conditions, surface silanes functionalization of MNPs was performed according to the reported study with minor modification [18]. In a typical experiment, 0.5% (v/v) silane solution was added to a dispersion of MNPs in hexane (30 mg in 10 mL) containing 0.01% (v/v) acetic acid. The mixture was shaken for one day and eventually a dark brown precipitate was obtained. During the magnetic separation step, MNPs were washed three times with hexane to remove excess silanes, followed by washing with ethanol to remove hexane. Then the product (silane-MNPs) was washed three times with deionized water and finally dispersed in water. Iron quantitative assessment of the yield of silane-MNPs was performed using inductively coupled plasma emission spectroscopy (ICP) [19].

Silanes-MNPs Treated for Zeta, UV–Vis Absorbance Measurements, and Cell Culture

To obtain protein-silane-MNPs conjugates, 1 mg of silane-MNPs (determined as iron) was incubated in 10 mL RPMI-1640 medium plus 10% FCS for 12 h. Then, the product thus obtained was separated by a magnet and washed three times to eliminate residual serum. The remnant RPMI-1640 medium was used for Coomassie blue fast staining and UV–vis measurements.

Cell Culture and Quantitative Cellular Uptake of MNPs

Human hepatoma cells (SMMC-7721) were used in in vitro experiments. Cells were cultured at 37 °C in a 5% CO2atmosphere, in a 24-well culture plate containing 0.6 mL RPMI-1640 medium plus 10% FCS. After washing twice with PBS to eliminate fetal calf serum, the cells were incubated with silane-MNPs and protein-silane-MNPs in RPMI-1640 without FCS for 12 h, respectively. Iron quantitative cellular uptake of nanoparticles was also determined based on ICP method. Three replicates were measured and the results were averaged with standard deviation.

Characterization

The size and morphology of the particles were determined by transmission electronic microscopy (TEM, JEOL, JEM-200EX) operating at 120 kV. Samples were dropped from hexane onto a carbon-coated copper grid and dried under room temperature. IR spectra were recorded on a Nicolet Nexus 870 FT-IR spectrometer and powder samples were dried at 100 °C under vacuum for 24 h prior to fabrication of the KBr pellet. Spectra were recorded with a resolution of 2 cm−1. Surface charge measurements were performed on a Zeta Potential Analyzer (Delsa 440SX, Beckman Coulter). ICP results were collected on a microplate reader (Model 680, Bio-RAD).

UV–vis spectra were recorded using a U-4100 spectrophotometer. To prepare Coomassie blue solution, 100 mg G-250 was dissolved in a mixture containing 45 mL ethanol and 5 mL water, followed by addition of 100 mL 85% phosphoric acid. The resulting solution was diluted to 1,000 mL with water. For UV–vis absorbance spectra measurements, 0.5 mL RPMI-1640 medium plus 10% FCS and 0.5 mL remnant RPMI-1640 medium which has been treated by silane-MNPs were added into 5 mL Coomassie blue solution, respectively. The resulting solution turned from black to blue and showed absorbance peak at 595 nm.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis, Surface Functionalization, and Characterization of MNPs

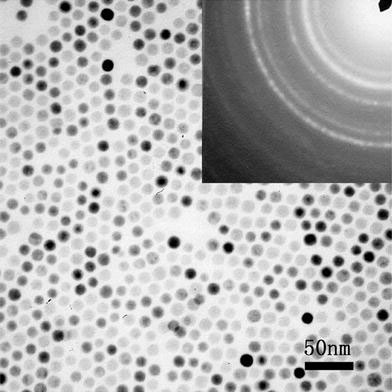

TEM image (Fig. 1) shows that MNPs synthesized by thermal decomposition of iron-oleate are well dispersed and have a uniform size of about 12 nm. An electron diffraction (ED) pattern (Fig. 1, inserted) confirms the inverse cubic spinel structure of Fe3O4. These Fe3O4MNPs are coated with oleic acid and thus organic-soluble. When functionalized by silanes with different functional groups, they become hydrophilic and represent different surface properties.

Figure 1.

TEM image of as-prepared oleic acid-coated Fe3O4MNPs. The insert is ED pattern of Fe3O4MNPs

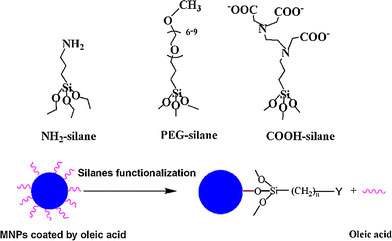

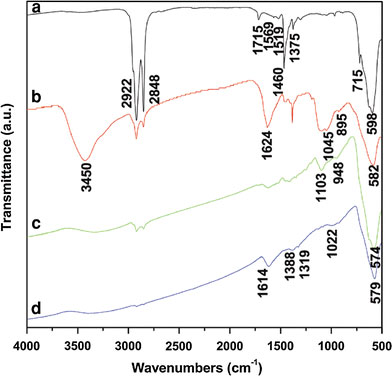

Silanes are bifunctional molecules with the chemical formula Y-(CH2)n-Si-R, where Y represents the functional groups and R is the methoxy or ethoxy groups. Figure 2a gives an overview of silanes containing NH2, PEG, and COOH functional groups, respectively. During the reaction of surface silanes functionalization, the methoxy or ethoxy groups of silanes easily hydrolyze leading to the formation of Fe–O–Si bond with Fe3O4 MNPs, as illustrated in Fig. 2b. Figure 3 demonstrates that silanes are successfully functionalized onto the surface of MNPs as evidenced in the IR spectra of oleic acid-coated MNPs and silane-MNPs. For oleic acid-coated MNPs, the sharp peak at 1,715 cm−1 assigned to carbonyl indicates that there exists free oleic acid. The peaks at 1,569 and 1,519 cm−1 are assigned to the symmetric and asymmetric COO− stretching, respectively. These latter two peaks indicate that oleic acid is bound to the surface of Fe3O4 MNPs through covalent bond between carboxylate (COOH) and Fe atom [20,21]. The band at 598 cm−1 confirms the nature of Fe3O4 MNPs. Furthermore, the two bands at 2,922 and 2,848 cm−1 are assigned to the asymmetric and symmetric CH2 stretching, respectively. The peaks at 1,460, 1,375, and 715 cm−1 are attributed to CH2 scissoring, CH3 bending, and (CH2)n vibration, respectively. For silanes-MNPs with NH2 (NH2-silanes-MNPs), the sharp peak at 3,450 cm−1 is assigned to NH2 vibration, and the bands at 1,624, 1,058, and 895 cm−1 correspond to NH2 scissoring, Si–O stretching and NH2 bending, respectively. The two bands at 1,103 and 948 cm−1 for PEG-silanes-MNPs are attributed to C–O–C vibration and CH2 rocking of PEG, respectively. For COOH-silanes-MNPs, the peaks at 1,614 and 1,388 correspond to the symmetric and asymmetric COO− stretching, respectively [18]. And the band at 1,022 cm−1 corresponds to Si–O stretching. Furthermore, the peak of Fe3O4 MNPs changes from 598 to 582, 574, and 579 cm−1 as a result of silanes functionalization. Thus, IR results confirm the successful surface silanes functionlization of Fe3O4 MNPs.

Figure 2.

The overview of silanes containing NH2, PEG and COOH functional groups and the illustration for the process of surface silanes functionalization of Fe3O4MNPs

Figure 3.

IR spectra of (a) as-prepared Fe3O4MNPs coated by oleic acid, (b) NH2−, (c) PEG, and (d) COOH-silanes-MNPs

Adsorption of Proteins from Culture Medium and its Effects on Surface Property of Silanes-MNPs

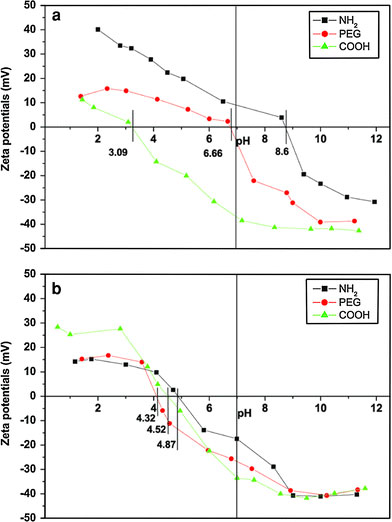

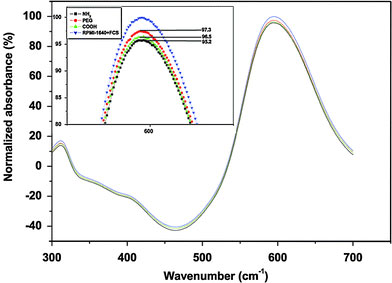

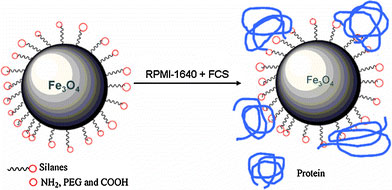

In general, to investigate interactions between MNPs and cancer cells, MNPs are incubated with the targeted cell in cell culture medium containing a lot of proteins. So it is important to clarify what happens to MNPs when they are incubated in cell culture medium. As is known, Zeta potential measurement is always used to determine the charge of the nanoparticles in different environments and estimate the isoelectric point (IEP), which is the pH at which there is no charge on the nanoparticles’ surface. Therefore, it is performed to investigate the change of silanes-MNPs’ surface charge before and after they are incubated in RPMI-1640 cell culture medium plus 10% fetal calf serum. In Fig. 4a, the surface charges of NH2, PEG and COOH-silanes-MNPs are about 15, −5 and −38 mV, respectively; the IEPs of NH2, PEG, and COOH-silanes-MNPs are observed at pH 8.6, 6.66, and 3.09, respectively. However, dramatic change in their surface charge occurs after silanes-MNPs are incubated in RPMI-1640 plus FCS for 12 h, as shown Fig. 4b. They are all negatively charged at neutral pH and their approximate IEPs are located between pH 4 and 4.5 where IEP of protein is located [22]. The change of surface property originates from adsorption of proteins in FCS onto silanes-MNPs’ surface, which is confirmed by Coomassie blue fast staining method. Coomassie blue (G-250) can react with proteins sensitively, resulting in the appearance of absorbance peak at 595 nm. The absorbance intensity is directly proportional to the amount of proteins. In Fig. 5, the peak of RPMI-1640 plus 10% FCS at 595 nm is normalized as 1, whereas the peak is decreased to 0.952, 0.973, and 0.965 after culture medium has been treated by NH2-, PEG-, and COOH-silanes-MNPs, respectively. It could be inferred that, for example, about 4.8% of proteins in 10 mL RPMI-1640 plus 10% FCS could be adsorbed onto the surface of 1 mg NH2-silanes-MNPs. Furthermore, compared to NH2- and COOH-silanes-MNPs, the amount of proteins adsorbed by PEG-silanes-MNPs was negligible, indicating protein-repellent property of PEG despite its low molecular weight and short chain used in this study. Based on the above investigations, we conclude that when silanes-MNPs are incubated in RPMI-1640 plus FCS, the formation of protein-silanes-MNPs conjugates is responsible for the change of their surface properties, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

Figure 4.

Zeta potentials of (a) silanes-MNPs and (b) protein-silanes-MNPs

Figure 5.

UV–vis absorbance of protein via Coomassie blue fast staining method. The insert is the enlarged image at 595 nm

Figure 6.

Schematic illustration for adsorption of protein in culture medium resulting in dramatic change of surface property of silanes-MNPs

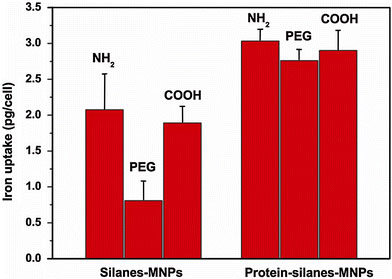

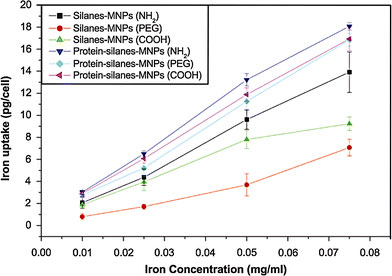

RPMI-1640 plus FCS is a familiar medium where both MNPs and cancer cells are incubated together; however, the original surface property of MNPs under such environment can be changed according to the above-mentioned results. It is well known that the interactions between MNPs and cancer cells are dependent not only on cell species [23], but also on the size [13] and surface properties of MNPs [11,24-26] including surface charge [27,28]. Among these factors, surface properties of MNPs may be the most important. So it is proposed that proteins from cell culture medium play a great role in the interactions between MNPs and cancer cells through their effects on surface property of MNPs. Therefore, the cellular uptake of silanes-MNPs and protein-silanes-MNPs by SMMC-7721 cells in RPMI-1640 without FCS is compared. As shown in Fig. 7, at low iron concentration (0.01 mg/mL), cellular uptake of protein-silanes-MNPs is much higher than that of silanes-MNPs because of the fact that the adsorption of proteins onto the surface of silanes-MNPs leads to non-targeting uptake by cancer cells. Especially, the uptake of PEG-silanes-MNPs is less than that of NH2 and COOH-silanes-MNPs; however, the uptake of all protein-silanes-MNPs is approximate. This demonstrates that although the amount of proteins adsorbed by PEG-silanes-MNPs is negligible compared to that adsorbed by NH2- and COOH-silane-MNPs, the effects derived from these adsorbed proteins are tremendous. Furthermore, we investigate the uptake of silanes-MNPs and protein-silanes-MNPs by SMMC-7721 with increasing iron concentrations, as shown in Fig. 8. The result shows that the cellular uptake of protein-silanes-MNPs by SMMC-7721 is higher than that of silanes-MNPs at different iron concentrations. The uptakes of both protein-silanes-MNPs and silanes-MNPs increases with increasing iron concentrations.

Figure 7.

Cellular uptakes of silanes-MNPs and protein-silanes-MNPs by SMMC-7721 at 0.01 mg/mL iron concentration

Figure 8.

Cellular uptakes of silanes-MNPs and protein-silanes-MNPs by SMMC-7721 at different iron concentrations

Conclusions

In summary, we investigated the effects of proteins from culture medium on the surface properties of MNPs functionalized with silanes bearing various functional groups such as NH2, PEG, and COOH. Despite the distinct surface properties, all the silanes-MNPs exhibited negative surface charges at neutral pH and approximate isoelectric points (IEP) when incubating in cell culture medium. This is due to adsorption of proteins onto the surface of silanes-MNPs and formation of protein-silanes-MNPs conjugates. Since surface was in direct contact with cells, surface property of MNPs is very important in the investigations on the interactions between MNPs and cancer cells. Therefore, we proposed that adsorbed proteins could play a great role in cellular uptake of MNPs by cancer cells, which was confirmed by in vitro cell experiments. The investigation on the effects of proteins from culture medium on MNPs’ surface property revealed in this study might be helpful both in in vitro and in vivo experiments.

Contributor Information

Y Zhang, Email: zhangyu@seu.edu.cn.

N Gu, Email: guning@seu.edu.cn.

Acknowledgments

This study has been carried out under financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 60571031, 60501009 and 90406023) and National Basic Research Program of China (No. 2006CB933200 and 2006CB705600). Open Project Foundation of Laboratory of Solid State Microstructures of Nanjing University is greatly appreciated.

References

- Xu CJ, Xu KM, Gu HW, Zhong XF, Guo ZH, Zheng RK, Zhang XX, Xu B. J. 2004. p. 3392. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXhsFyitrw%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Huh YM, Jun YW, Song HT, Kim S, Choi JS, Lee JH, Yoon S, Kim KS, Shin JS, Suh JS, Cheon J. J. 2005. p. 12387. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2MXnslOrtbw%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tromsdorf UI, Bigall NC, Kaul MG, Bruns OT, Nikolic MS, Mollwitz B, Sperling RA, Reimer R, Hohenberg H, Parak WJ, Forster S, Beisiegel U, Adam G, Weller H. Nano Lett. 2007. p. 2422. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2sXnvFegt70%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jun YW, Huh YM, Choi JS, Lee JH, Song HT, Kim S, Yoon S, Kim KS, Shin JS, Suh JS, Cheon J. J. 2005. p. 5732. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2MXivVert7o%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jordan A, Scholz R, Maier-Hauff K, Johannsen M, Wust P, Nadobny J, Schirra H, Schmidt H, Deger S, Loening S, Lanksch W, Felix R. J. 2001. p. 118. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3MXislaiurc%3D]; Bibcode number [2001JMMM..225..118J] [DOI]

- Xu RZ, Zhang Y, Ma M, Xia JG, Liu JW, Guo QZ, Gu N. IEEE Trans. 2007. p. 1078. Bibcode number [2007ITM....43.1078X] [DOI]

- Kohler N, Sun C, Fichtenholtz A, Gunn J, Fang C, Zhang MQ. Small. 2006. p. 785. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD28XkslOmtr4%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hong R, Fischer NO, Emrick T, Rotello VM. Chem. Mater. 2005. p. 4617. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2MXmvFCnu7s%3D] [DOI]

- Kohler N, Fryxell GE, Zhang MQ. J. 2004. p. 7206. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXktFCqtLg%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yang J, Lee TI, Lee J, Lim EK, Hyung W, Lee CH, Song YJ, Suh JS, Yoon HG, Huh YM, Haam S. Chem. 2007. p. 3870. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2sXnslOmsro%3D] [DOI]

- Zhang Y, Zhang J. J. 2005. p. 352. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2MXhsVGnsLc%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mohapatra S, Mallick SK, Maiti TK, Ghosh SK, Pramanik P. Nanotechnology. 2007. p. 385102. Bibcode number [2007Nanot..18L5102M] [DOI]

- Chithrani BD, Ghazani AA, Chan WCW. Nano Lett. 2006. p. 662. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD28XhvVCjsLk%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Casey A, Davoren M, Herzog E, Lyng FM, Byrne HJ, Chambers G. Carbon. 2007. p. 34. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2sXhtFCltLY%3D] [DOI]

- Zhu Y, Ran TC, Li YG, Guo JX, Li WX. Nanotechnology. 2006. p. 4668. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD28XhtFKjtr7J]; Bibcode number [2006Nanot..17.4668Z] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chen ZP, Zhang Y, Xu K, Xu RZ, Liu JW, Gu N. J. in press . [PubMed]

- Park J, An KJ, Hwang YS, Park JG, Noh HJ, Kim JY, Park JH, Hwang NM, Hyeon T. Nat. 2004. p. 891. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXhtVehtrjM]; Bibcode number [2004NatMa...3..891P] [DOI] [PubMed]

- De Palma R, Peeters S, Van Bael MJ, Van den Rul H, Bonroy K, Laureyn W, Mullens J, Borghs G, Maes G. Chem. 2007. p. 1821. [DOI]

- Gupta AK, Gupta M. Biomaterials. 2005. p. 1565. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXptV2ltL0%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Willis AL, Turro NJ, O’Brien S. Chem. 2005. p. 5970. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2MXhtFOhsL7M] [DOI]

- Zhang L, He R, Gu HC. Appl. 2006. p. 2611. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD28Xht1Kmur7M]; Bibcode number [2006ApSS..253.2611Z] [DOI]

- Mikhaylova M, Kim DK, Berry CC, Zagorodni A, Toprak M, Curtis ASG, Muhammed M. Chem. 2004. p. 2344. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXktVSlsrc%3D] [DOI]

- Kohler N, Sun C, Wang J, Zhang MQ. Langmuir. 2005. p. 8858. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2MXnslOrsL8%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Kohler N, Zhang MQ. Biomaterials. 2002. p. 1553. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD38XhtFykurY%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hu FX, Neoh KG, Kang ET. Biomaterials. 2006. p. 5725. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD28Xos12qtbo%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]

- Selim KMK, Ha YS, Kim SJ, Chang Y, Kim TJ, Lee GH, Kang IK. Biomaterials. 2007. p. 710. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Patil S, Sandberg A, Heckert E, Self W, Seal S. Biomaterials. 2007. p. 4600. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2sXptFygurg%3D] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chung TH, Wu SH, Yao M, Lu CW, Lin YS, Hung Y, Mou CY, Chen YC, Huang DM. Biomaterials. 2007. p. 2959. COI number [1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2sXktFOktL4%3D] [DOI] [PubMed]