Abstract

Reductionist attempts to dissect complex mechanisms into simpler elements are necessary, but not sufficient for understanding how biological properties like reward emerge out of neuronal activity. Recent studies on intracranial self-administration of neurochemicals (drugs) found that rats learn to self-administer various drugs into the mesolimbic dopamine structures–the posterior ventral tegmental area, medial shell nucleus accumbens and medial olfactory tubercle. In addition, studies found roles of non-dopaminergic mechanisms of the supramammillary, rostromedial tegmental and midbrain raphe nuclei in reward.

To explain intracranial self-administration and related effects of various drug manipulations, I outlined a neurobiological theory claiming that there is an intrinsic central process that coordinates various selective functions (including perceptual, visceral, and reinforcement processes) into a global function of approach. Further, this coordinating process for approach arises from interactions between brain structures including those structures mentioned above and their closely linked regions: the medial prefrontal cortex, septal area, ventral pallidum, bed nucleus of stria terminalis, preoptic area, lateral hypothalamic areas, lateral habenula, periaqueductal gray, laterodorsal tegmental nucleus and parabrachical area.

Keywords: Motivation, Affective arousal, Conditioned place preference, Module, Median and dorsal raphe nuclei, GABA, Glutamate, Seeking, Depression, Mania, Addiction

1. Introduction

Reward research has traditionally focused on brain dopamine. Early experiments showed that systemic injections of low doses of dopamine receptor antagonists exert extinction-like effects on instrumental responding maintained by food or brain stimulation reward (Wise, 1982) and that drugs abused by humans increase extracellular dopamine in the brain (Di Chiara and Imperato, 1988). Although dopamine’s exact functions must still be clarified, the notion that dopamine plays a role in simple sensory pleasure is disputed. For example, the blockade of dopamine receptors in the ventral striatum disrupts instrumental responding for sucrose solutions, but not the consumption of sucrose (Ikemoto and Panksepp, 1996); similarly, lesions of dopamine terminals do not disrupt oral movements associated with palatable food (Berridge and Robinson, 1998). Dopamine appears to play a key role in reward in the sense that it energizes approach and induces conditioned approach (Ikemoto and Panksepp, 1999; Ikemoto, 2007).

The site of dopamine’s release appears to determine the role that it plays. A major source of brain dopamine is localized in the ventral midbrain – ventral tegmental area (VTA) and substantia nigra, which primarily projects to the striatal complex – ventral striatum (VS) and dorsal striatum, in mediolateral topography. In turn, the striatal complex projects to both the pallidum and the ventral midbrain in mediolateral topography. The existence of a largely parallel organization of circuits linking the striatal complex to the midbrain and pallido-thalamo-cortex suggests that dopamine’s function depends on its release site (Alexander et al., 1986; Haber, 2003; Ikemoto, 2007; Voorn et al., 2004; Yin and Knowlton, 2006). Drug self-administration and electrical self-stimulation studies have shown that dopaminergic projection from the VTA to the VS is particularly important in reward (Fibiger and Phillips, 1986; Koob, 1992; McBride et al., 1999; Pierce and Kumaresan, 2006; Wise and Bozarth, 1987). For example, depletion of dopamine in the VS or VTA severely attenuates instrumental responding for cocaine or amphetamine (Lyness et al., 1979; Roberts and Koob, 1982; Roberts et al., 1977, 1980). Moreover, rats learn to self-administer amphetamine, cocaine or dopamine receptor agonists directly into the VS (Carlezon et al., 1995; Hoebel et al., 1983; Ikemoto et al., 1997a; Rodd-Henricks et al., 2002), suggesting that increased dopamine transmission is rewarding. More recent intracranial self-administration studies suggest that the medial part of the VTA–VS dopamine system plays a more important role in triggering reward than the lateral part (Ikemoto, 2007).

It seems logical that while dopamine plays a key role in reward, it is not a sole mediator. Most biological properties arise from the collective properties of many components: Reductionist approach of dissecting mechanisms into smaller elements is necessary but not sufficient for understanding how biological properties emerge (Hartwell et al., 1999). However, circuitry through which dopamine mediates reward is not clearly understood. The major claim of this paper is that the medial VTA–VS dopamine system’s ability to mediate reward arises from its interactions with certain brain structures that collectively coordinate various selective functions (including perceptual, visceral and reinforcement processes) for a global function of approach. To support this claim, I will first review findings from self-stimulation studies that suggest that no single region is responsible for reward, supporting the view that reward arises from interactions of neurons localized over multiple brain regions (Section 2). I will next describe recent intracranial self-administration studies that show that the medial part of the VTA–VS dopamine system is particularly important for mediating reward, and that other neurotransmitters in other regions such as GABAergic and glutamatergic mechanisms in the supramammillary and midbrain raphe nuclei also mediate reward (Section 3). Section 4 presents a theoretical framework that provides explanations for intracranial self-administration findings. I will also review findings that support this neurobiological theory of reward. Section 5 reviews tract tracer data suggesting that drug trigger zones for reward are closely connected with certain brain regions that are associated with visceral and arousal functions. I propose that they are key components of the brain reward circuitry through which dopamine mediates reward.

2. Lessons from self-stimulation studies: reward emerges from dynamic interactions of neurons localized in multiple brain regions

Olds and Milner (1954) discovered that rats learn an instrumental task to deliver brief (typically less than 1 s) electrical stimulation through an implanted electrode aimed at a discrete brain site. This behavior is referred to as intracranial self-stimulation. Previous studies have shown that brain sites supporting self-stimulation in rats are widespread, yet associated with specific structures including the olfactory bulb and specific subregions of the cortex, hypothalamus, midbrain and hindbrain (Olds and Peretz, 1960; Olds and Olds, 1963; Phillips and Mogenson, 1969; Routtenberg and Malsbury, 1969; Routtenberg and Sloan, 1972). Self-stimulation has been studied most extensively with stimulation delivered at the lateral hypothalamic medial forebrain bundle, since this manipulation supports fast and persistent self-stimulation. When stimulation parameters are optimized, many rats learn to respond 100 or more times per minute and maintain fast self-stimulation for hours until the point of physical exhaustion (Olds, 1958a). They will run across aversive shock grids or ignore warning signals of shock to pursue self-stimulation (Olds, 1958b; Valenstein and Beer, 1962) and will starve themselves if food is only available at the same time as self-stimulation sessions (Routtenberg and Lindy, 1965). Such robust motivated behavior for brain stimulation reward prompted investigators to seek its neural substrates, particularly using pharmacological and lesion procedures.

Pharmacological investigations found that dopamine transmission, particularly in the VTA–VS dopamine system, plays a critical role in self-stimulation (Fibiger, 1978; Wise, 1978). For example, self-stimulation at the medial forebrain bundle is reduced by microinjections of dopamine receptor antagonists into the VS, but not into the dorsal striatum (Stellar and Corbett, 1989; Stellar et al., 1983), whereas self-stimulation is facilitated by injections of amphetamine into the VS (Colle and Wise, 1988). Intriguingly, electrophysiological studies suggest that electrical stimulation reward at the medial forebrain bundle does not directly activate dopamine neurons, which ascend through the medial forebrain bundle, but instead activates non-dopaminergic, myelinated axons coursing in the descending direction (Gallistel et al., 1981; Shizgal, 1989; Yeomans, 1989). Therefore, dopamine neurons appear to be secondarily recruited by brain stimulation reward only after the activation of other substrates.

Lesion studies suggest that beyond the site of stimulation, no single brain region is critically responsible for self-stimulation (Lorens, 1976; Valenstein, 1966; Waraczynski, 2006). Self-stimulation at the lateral hypothalamic medial forebrain bundle, for example, is not abolished by lesions, such as extensive knife cuts just anterior or posterior to the stimulation site (Gallistel et al., 1996; Janas and Stellar, 1987; Lorens, 1966; Stellar et al., 1991), which disconnect most of the dopaminergic ascending fibers. Other lesion studies also suggest that the VTA–VS dopamine system is not necessary for self-stimulation (Fibiger et al., 1976, 1987; Johnson and Stellar, 1994; Sidhu et al., 1993; Simon et al., 1979). It is likely that stimulation at the lateral hypothalamic medial forebrain bundle simultaneously stimulates multiple pathways underlying reward.

Self-stimulation research findings have two important implications for the structural organization of reward function. One is that a single brain region is not large enough to contain sufficient reward mechanisms. Instead, reward appears to arise from structures localized over multiple brain regions. The other is that brain stimulation reward is likely not mediated by serial circuits, but by networks of neurons and regions acting both in serial and parallel fashion (Ikemoto and Panksepp, 1994). This view is consistent with observations that highly interconnected anatomical architectures of brain regions associated with brain stimulation reward (which will be discussed in Section 5), and that networks are highly resistant to local insults (Albert et al., 2000; Alstott et al., 2009).

3. Intracranial self-administration studies

Brain stimulation reward experiments are useful in many ways, but suffer from some shortcomings. The parameters of electrical stimulation that are routinely used for self-stimulation most likely excite axons of passage rather than cell bodies and myelinated rather than unmyelinated axons (Ranck, 1975). This property of brain stimulation reward makes it difficult to define what exactly the stimulation is activating. For example, rats learn to self-stimulate at the VTA; yet, it is unclear what exactly is stimulated.

Thus, the intracranial drug self-administration procedure has the advantage of enabling researchers to define reward-mediating receptors (i.e., neurotransmitters) while avoiding influence on fibers of passage, and – with proper anatomical controls – brain regions or even subregions containing receptors that mediate reward (Ikemoto and Wise, 2004). This approach can also help to identify regions that contribute to reward through not only via their excitation, but also through their inhibition. In intracranial self-administration, animals typically receive a small volume (50–100 nl) of a solution containing chemicals that act selectively at known receptors (thereafter, these chemicals are referred to as drugs, including non-selective ones such as amphetamine and cocaine). Summarized below are findings on intracranial self-administration of drugs into the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system, and other regions including the supramammillary (SUM), midbrain raphe and rostromedial tegmental (RMTg) nuclei.

3.1. Findings on the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system

As discussed above, the VTA–VS dopamine system is critically involved in drug self-administration, and also plays important roles in other appetitive behaviors and self-stimulation (Fibiger and Phillips, 1986; Ikemoto and Panksepp, 1999; Pierce and Kumaresan, 2006; Wise and Bozarth, 1987). This assertion is based on findings using various procedures including dopamine receptor antagonists, 6-OHDA lesions, in vivo dopamine concentration measurements in appetitive behavior. Recent studies suggest that the VTA–VS dopamine system is not functionally homogeneous. The medial part of the VTA–VS dopamine system appears to be particularly important for reward and arousal, and that the lateral portion is more closely involved in specific conditioned responses than the medial (Ikemoto, 2007).

3.1.1. Ventral tegmental area (VTA)

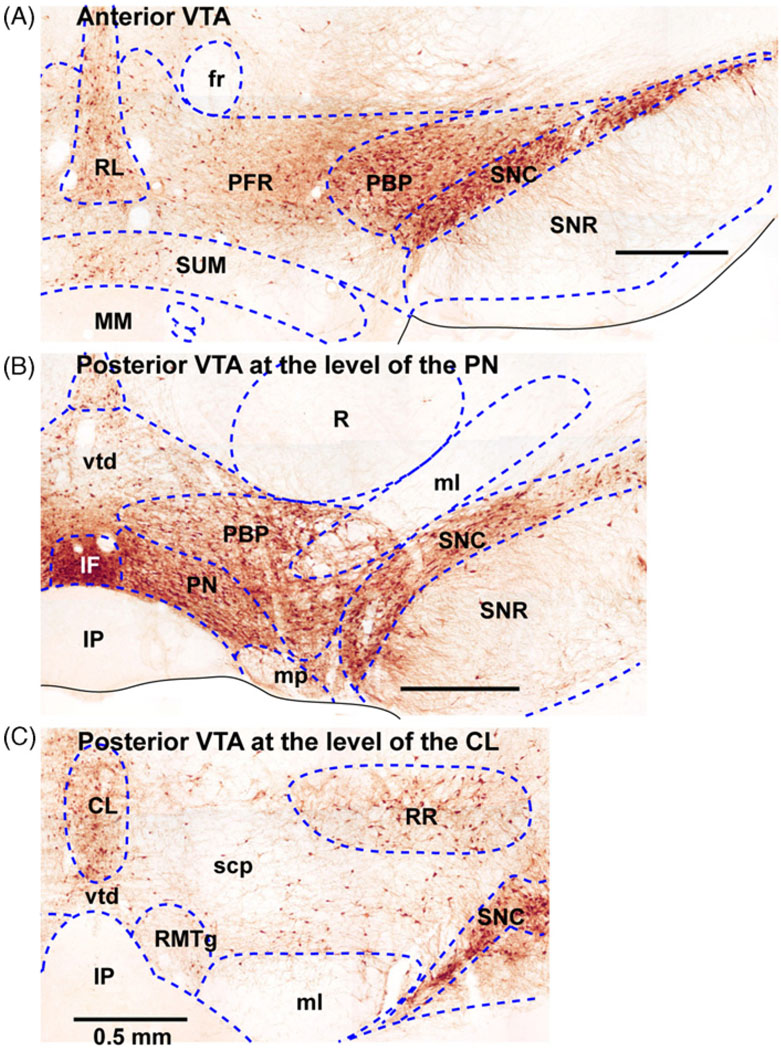

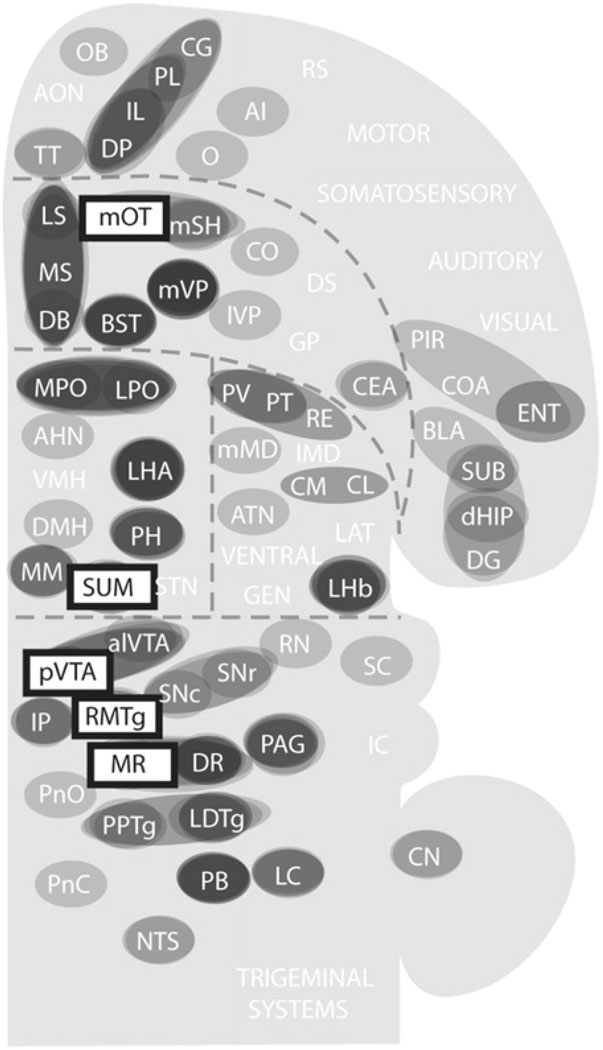

Careful examination of the VTA cytoarchitecture reveals that this site consists of heterogeneous elements (Fig. 1) (Olson and Nestler, 2007; Phillipson, 1979b; Yamaguchi et al., 2007). Intracranial self-administration data suggest that the VTA is functionally heterogeneous and that the posterior VTA, including the central linear nucleus, is more important than the anterior VTA for drug self-administration. Initial behavioral studies suggested that GABA receptor antagonists administered into the anterior, but not posterior, portion of the VTA are rewarding (Ikemoto et al., 1997b) and facilitate locomotion (Arnt and Scheel-Kruger, 1979), whereas GABA receptor agonists administered into the posterior, but not anterior, portion of the VTA are rewarding (Ikemoto et al., 1998) and facilitate locomotion (Arnt and Scheel-Kruger, 1979). These findings prompted additional investigations which demonstrated that rats learn to self-administer many drugs into the posterior VTA more vigorously than the anterior. These include cholinergic drugs (carbachol, neostigmine and nicotine) (Ikemoto et al., 2006; Ikemoto and Wise, 2002), opiates (endomorphin-1) (Zangen et al., 2002), cannabinoids (Δ9THC) (Zangen et al., 2006), cocaine (Rodd et al., 2005a), alcohol-related chemicals (ethanol, acetaldehyde and salsolinol) (Rodd et al., 2005b, 2004, 2008), serotonin-3 receptor agonists (Rodd et al., 2007). The GABA receptor agonist muscimol is selectively self-administered into the posterior VTA, but its effective zone appears to be limited in the central linear nucleus of the VTA (Fig. 1C) (Ikemoto et al., 1998). Fig. 2 summarizes effective sites of nicotine self-administration. These drugs are either not self-administered into the anterior VTA or self-administered into the anterior VTA less vigorously than into the posterior VTA. Thus, the initial finding on the rewarding effects of GABA receptor antagonists in the anterior VTA has been reinterpreted in light of further studies on the nearby SUM (see Section 3.2 below). It should be noted that the drugs listed above may be acting at any number of cell types because the VTA contains various input terminals and other types of neurons besides dopamine neurons, including GABA and glutamate neurons (Olson and Nestler, 2007; Yamaguchi et al., 2007).

Fig. 1.

Coronal sections of the ventral tegmental area. Three sections from the anterior to posterior (A, B and C) are shown to illustrate differential cytoarchitectonic features within the ventral tegmental area. Sections are stained with tyrosine hydroxylase, which indicates dopaminergic neurons in this area of the brain. Abbreviations: CL, central (or caudal) linear nucleus raphe; fr, fasciculus retroflexus; IF, interfascicular nucleus; IP, interpeduncular nucleus; ml, medial lemniscus; PBP, parabrachial pigmented area; PFR, parafasciculus retroflexus area; PN, paranigral nucleus; R, red nucleus; RL, rostral linear nucleus raphe; RR, retrorubral nucleus; scp, superior cerebellar peduncle; SNC, substantia nigra compact part; SNR, substantia nigra reticular part; SUM, supramammillary nucleus; vtd, ventral tegmental decussation.

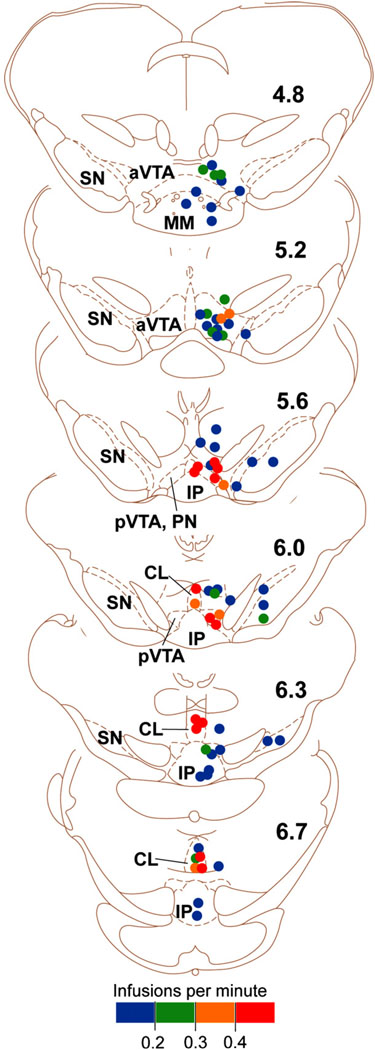

Fig. 2.

Effectiveness of nicotine self-administration into the ventral tegmental area. Each dot on the coronal sections summarizes self-administration data from a single rat. Its color indicates the rate of self-administration of nicotine at the site. The numbers on the right indicate distances (mm) from bregma. The figure is modified from the one originally presented in the Ikemoto et al. study (2006) and presented with permission from the Society for Neuroscience. Drawings are adapted and modified from the rat atlas by Paxinos and Watson (1997). Abbreviations: aVTA, anterior ventral tegmental area; CL, central (or caudal) linear nucleus raphe; IP, interpeduncular nucleus; pVTA, posterior ventral tegmental area; SN, substantia nigra.

3.1.2. Ventral striatum (VS)

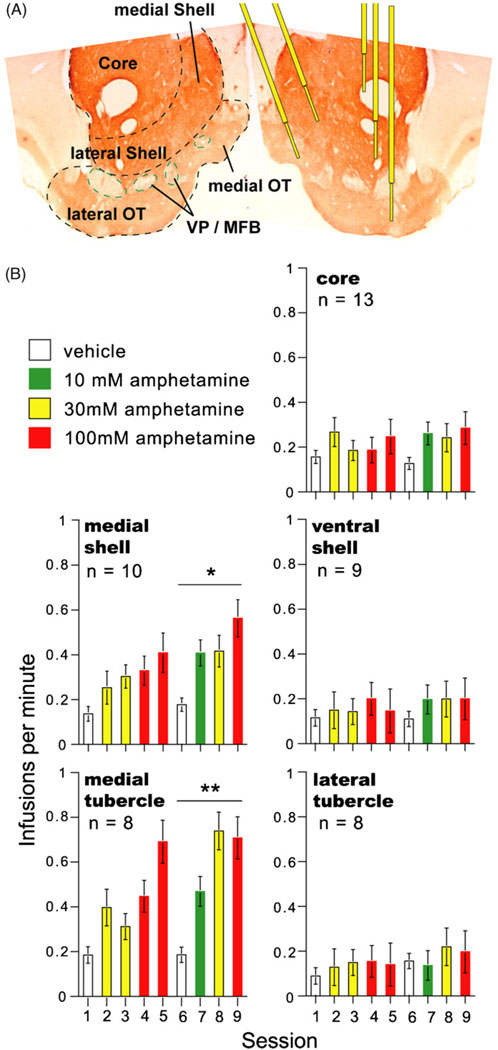

The nucleus accumbens consists of anatomically heterogeneous elements (Fig. 3A) (Heimer et al., 1997). It has received intense research attention for its reward-related functions, which have been investigated with respect to the accumbens core and shell. It was shown that rats learn to self-administer dopaminergic drugs (cocaine, nomifensine and D1/D2 receptor agonists) into the shell of the nucleus accumbens more vigorously than the accumbens core (Carlezon et al., 1995; Ikemoto et al., 1997a; Rodd-Henricks et al., 2002). Subsequent studies suggested that within the accumbens shell, the medial portion is more responsive to psychomotor stimulants than its lateral counterpart (Ikemoto et al., 2005; Shin et al., 2008). In addition to dopaminergic drugs, the medial shell, but not the core, supports self-administration of glutamate NMDA receptor antagonists (Carlezon and Wise, 1996) and Δ9THC (Zangen et al., 2006).

Fig. 3.

The ventral striatum and self-administration of amphetamine. (A) Divisions of the ventral striatum and cannula placements are shown on the right and left, respectively. The coronal section is stained with tyrosine hydroxylase. (B) Mean self-administration rates for the five subregions of the ventral striatum. During sessions 6–9, rats receiving amphetamine into the medial olfactory tubercle and medial shell self-administered at greater rates than those receiving the drug into the lateral tubercle, lateral shell, or core, *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. The figure is modified from one originally presented in the Ikemoto et al. study (2005) and presented with permission from the Society for Neuroscience.

The olfactory tubercle, located just ventral to the nucleus accumbens, consists of heterogeneous elements including the medial forebrain bundle/ventral pallidal portion, the islands of Calleja, and the most ventral extension of the striatal complex (Fig. 3A). In the 1970s it was recognized that the olfactory tubercle contains a striatal component, which is filled with GABAergic medium spiny neurons receiving glutamatergic inputs form cortical regions and dopaminergic inputs from the VTA and projecting to the ventral pallidum just like the nucleus accumbens (Heimer, 1978; Heimer and Wilson, 1975). General lack of the recognition of the olfactory tubercle as a striatal structure may partly explain why, until recently, only a handful of studies examined its functional properties (e.g., Clarke et al., 1990; Cools, 1986; Kornetsky et al., 1991; Prado-Alcala and Wise, 1984).

Recent studies found that rats also learn to self-administer cocaine or amphetamine into the olfactory tubercle (Ikemoto, 2003; Ikemoto et al., 2005). This rewarding effect is readily diminished by co-administration of dopamine receptor antagonists. Fig. 3B summarizes findings on intracranial self-administration of d-amphetamine into the VS. As with the accumbens, the medial portion of the olfactory tubercle supports more vigorous self-administration than its lateral portion. In summary, the medial portion of the VS (i.e., the medial olfactory tubercle and medial accumbens shell) appears to be more responsive to the rewarding effects of dopaminergic drugs than its lateral counterpart.

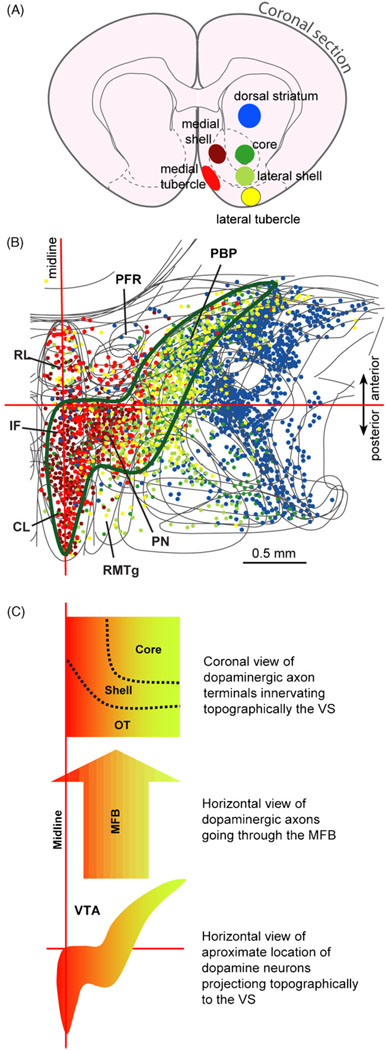

3.1.3. The medial VTA–VS dopamine system

Previous studies suggested that dopamine neurons localized in the ventral midbrain, including the VTA and substantia nigra, project to the ventral and dorsal striatum with mediolateral topography (Beckstead et al., 1979; Fallon and Moore, 1978). This notion of mediolateral topography initially did not seem to be helpful for understanding the functional heterogeneity between the anterior and posterior VTA. However, our retrograde tracer studies, focusing on fine details within the VS and VTA, suggest that the medial VS receives the majority of dopaminergic inputs from the posterior VTA, while the lateral VS receives a majority of dopaminergic inputs from the lateral, particularly the anterolateral, VTA (Ikemoto, 2007). A close examination of the locations of dopamine neurons suggest that dopamine neurons projecting to the medial VS are localized posteromedially in the VTA in relation to those projecting to the lateral VS (Fig. 4). Therefore, the functional heterogeneity of the VTA and VS found in intracranial self-administration can be explained by the fact that drug injections into the posterior VTA readily activate dopamine neurons projecting to the medial VS, leading presumably to localized increases in concentrations of dopamine, as well as rewarding effects. In contrast, drug injections into the anterior VTA do not readily activate those neurons projecting to the medial VS, failing to significantly increase dopamine concentration there. These behavioral and tracer studies suggest that the most ventromedial part of the basal ganglia is uniquely involved in drug-triggered reward.

Fig. 4.

Topographic projection of midbrain dopamine neurons to the ventral striatum. (A) The retrograde tracer Fluorogold was iontophoretically injected into the subregions of the ventral striatum and dorsal striatum. Different colors are used to distinguish injection sites from each other. (B) Retrogradely labeled neurons were plotted on horizontal sections of the ventral midbrain. Each dot represents a neuron retrogradely-labeled by one of the injection sites (color coded). Approximate area that provides dopaminergic projection to the ventral striatum is outlined by green line. See the legend of Figure 1 for abbreviations. (C) Highly schematic drawing shows mediolateral topography of dopamine neuron projection between the VTA and ventral striatum. The figure is modified from one originally presented in the review (Ikemoto, 2007) and presented with permission from Elsevier.

3.1.4. The prefrontal cortex

Intracranial self-administration studies also found that rats learn to self-administer drugs, including cocaine, into the medial prefrontal cortex, another projection region of the VTA. Although no study has systematically examined its effective zone within the prefrontal cortex, rats learn to self-administer cocaine (Goeders and Smith, 1983; Goeders et al., 1986) and NMDA receptor antagonists–phencyclidine, MK-801, and 3-((±)2-carboxypiperazin-4yl)propryl-1-phosphate (Carlezon and Wise, 1996)–into the vicinity of the prelimbic area of the medial prefrontal cortex.

In addition to the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system, recent intracranial self-administration studies found other brain regions that are importantly involved in reward. These zones include the SUM, midbrain raphe nuclei, and RMTg, which appear to interact with the VTA–VS dopamine system.

3.2. The supramammillary nucleus (SUM) as a trigger zone for reward

The SUM is localized in the posterior hypothalamic area, just anterior to the VTA and just dorsal to the mammillary body. The posterior part of the SUM is localized just ventromedial to the anterior VTA (Fig. 1A). The SUM was initially implicated in reward by the finding that rats learn to self-stimulate at the vicinity of the SUM (Olds and Olds, 1963). However, this report did not prompt investigation of the role this structure plays in reward and motivation. After the 1970s and 1980s, when dopamine neurons projecting from the VTA were recognized as being critical for reward, the SUM was put aside. Until recently, functional investigation of the SUM was largely limited to its role in hippocampal theta rhythm (Pan and McNaughton, 2004).

In fact, when rats were found to self-administer GABAA receptor antagonists such as picrotoxin and bicuculline into the vicinity of the anterior VTA/SUM, the rewarding effects were largely attributed to the VTA (David et al., 1997; Ikemoto et al., 1997b). However, a subsequent study clarified that the SUM mediates the rewarding effects of GABAA receptor antagonists (Ikemoto, 2005). Rats self-administer picrotoxin into the SUM at a lower concentration and at higher rates than into the anterior VTA. Therefore, the rewarding effects of GABAA receptor antagonists administered into the anterior VTA can be explained by the diffusion of the drugs into the SUM, not vice versa. This view is reinforced by the above mentioned observations that none of the drugs that were examined for the VTA were self-administered into the anterior VTA more effectively than into the posterior VTA (Ikemoto et al., 1998, 2006; Ikemoto and Wise, 2002; Rodd et al., 2004, 2005a, 2005b, 2007, 2008; Zangen et al., 2002, 2006). In addition to GABAA receptor antagonists, the SUM was found to support self-administration of nicotine (Ikemoto et al., 2006) and the glutamate receptor agonist AMPA (Ikemoto et al., 2004). These drugs, unlike GABAA receptor antagonists, are not self-administered into the anterior VTA, and AMPA injections into this subarea induce aversive effects (Ikemoto et al., 2004).

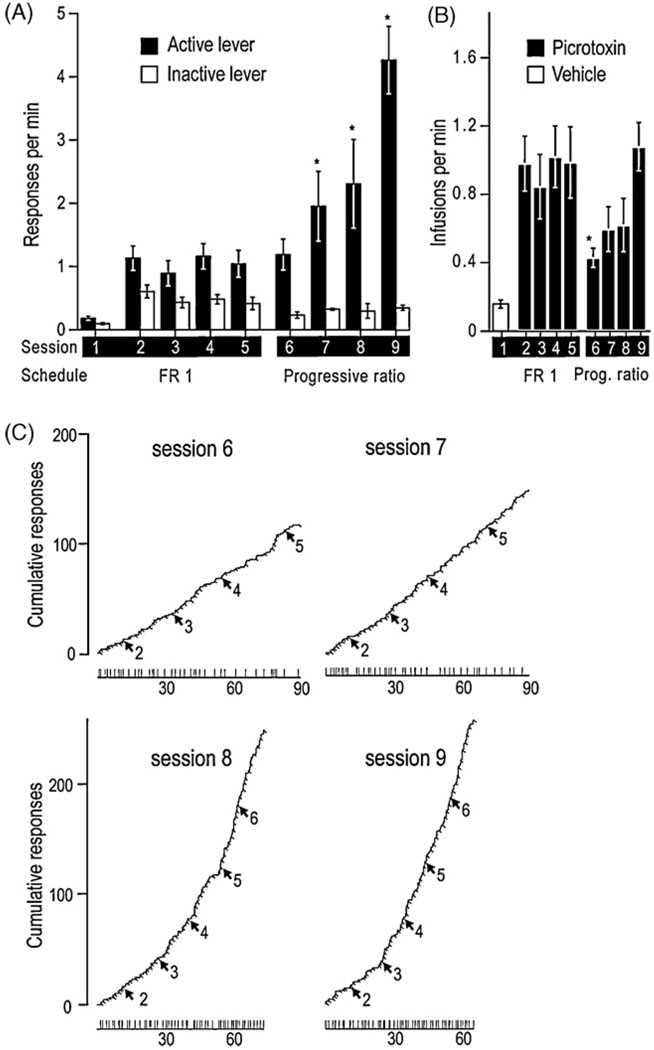

Picrotoxin administration into the SUM is one of the most robust instigators of intracranial self-administration that has been found. This manipulation supports self-administration faster than cocaine or amphetamine administration into the medial olfactory tubercle (Ikemoto, 2003; Ikemoto et al., 2005) and as fast as the administration of cholinergic agents carbachol or neostigmine into the posterior VTA (Ikemoto and Wise, 2002). Although faster rates of self-administration do not necessarily imply that the drug is more rewarding, picrotoxin injections into the SUM also support persistent self-administration. A modified progressive ratio experiment showed that rats learn to increase rates of leverpressing over sessions when the requirement for an infusion of picrotoxin increases (Fig. 5)(Ikemoto, 2005). This is the first intracranial self-administration demonstration that rats learn to increase rates of responding to maintain local injections.

Fig. 5.

Effects of a progressive ratio schedule on supramammillary injections of picrotoxin. Four rats received vehicle in session 1 and picrotoxin (0.1 mM) in sessions 2–9. They were trained on operant conditioning schedules of a fixed-ratio 1 with a 20 s timeout in sessions 1–5 and a partial progressive ratio (up to 6) in sessions 6–9. (A) Mean response rates (±SEM) of the two levers are summarized over nine sessions. Active lever-presses in each of sessions 7, 8, and 9 were greater than inactive lever-presses in respective sessions, and they were also greater than active lever-presses in each of sessions 2, 3, 4, and 5 (*P < 0.05). (B) Mean infusion rates (±SEM) are shown over nine sessions. The infusions in session 6, when the progressive ratio schedule was introduced, were lower than those in sessions 2,4, and 5 (*P < 0.05). (C) Cumulative response records and infusion event records of a representative rat are shown. Each line moves up a unit vertically every time the rat pressed the active lever. Each perpendicular slit indicates the point of an infusion delivery. Each arrow accompanied by a number indicates the point at which the response requirement was incremented, and the number indicates required lever-presses for each infusion. The horizontal lines in the bottom indicate session length with vertical lines again indicating the points of infusions delivered. The figure is modified from one originally presented in the Ikemoto study (2005) and presented with permission from Nature Publishing Group.

3.3. Functional interaction between the SUM and the VTA–VS dopamine system

Supramammillary neurons appear to reciprocally interact with the VTA–VS dopamine system. AMPA administration into the SUM is rewarding and also increases extracellular dopamine concentrations in the medial VS as measured by microdialysis (Ikemoto et al, 2004). In addition, self-administration of AMPA or picrotoxin into the SUM is readily disrupted by a low dose systemic administration of dopamine receptor antagonists. These findings suggest that the stimulation of supramammillary neurons subsequently activates the VTA–VS dopamine system.

Conversely, some manipulations that stimulate VTA dopamine neurons appear to activate supramammillary neurons. As mentioned above, rats learn to self-administer the cholinergic receptor agonist carbachol into the posterior VTA (Ikemoto and Wise, 2002), a manipulation that is one of the most effective at supporting intracranial self-administration and increasing extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens (Westerink et al., 1996). The administration of carbachol into the posterior VTA was found to increase the transcription factor c-Fos in the SUM (Ikemoto et al., 2003). Supramammillary c-Fos counts were positively correlated with locomotor counts increased by carbachol administration into the VTA. These findings are consistent with the view that the VTA and SUM reciprocally interact with each other. However, it is unclear how VTA neurons activate supramammillary neurons and vice versa. This issue will be discussed in Section 5.

3.4. Possible inhibitory control by midbrain structures

3.4.1. Midbrain raphe nuclei

Stimulation applied at the lateral hypothalamic medial forebrain bundle was initially regarded as the most powerful for supporting self-stimulation, in terms of rate and persistence of responding (Olds, 1962). However, subsequent studies suggested that similarly vigorous self-stimulation could be elicited at the vicinity of the median (MR) or dorsal (DR) raphe nuclei (Miliaressis et al., 1975; Rompré and Boye, 1989; Rompré and Miliaressis, 1985). Intracranial self-administration studies suggest that the inhibition, rather than stimulation, of midbrain raphe neurons is rewarding. Fletcher and colleagues found that microinjections of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OH-DPAT into the MR or DR, manipulations that inhibit serotonergic neurons, induce conditioned place preference (Fletcher et al., 1993) and facilitate lateral hypothalamic self-stimulation (Fletcher et al., 1995). Our group provided further evidence that the inhibition of neurons in the MR and DR is rewarding using GABAergic receptor agonists and glutamatergic receptor antagonists administered into these nuclei. We found that rats readily learn to self-administer the GABAA receptor agonist muscimol or the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen into the MR or DR (Liu and Ikemoto, 2007; Shin and Ikemoto, 2010b). We also found that rats learn to self-administer AMPA or NMDA receptor antagonists ZK-200775 or AP-5 into these regions (Webb et al., 2009). Overall the self-administration data suggests that inhibition of midbrain raphe neurons is rewarding.

Self-administration of muscimol or baclofen appears to depend on intact dopamine transmission, since it is readily disrupted by a low dose of systemic administration of dopamine receptor antagonists. Consistently, muscimol injections into the MR increase the ratios of DOPAC or HVA to dopamine in post mortem accumbens tissues (Wirtshafter and Trifunovic, 1992), suggesting that these manipulations increase extracellular dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens. There is also evidence that these effects of intra-MR muscimol are largely independent of serotonergic neurons, despite their abundance in the raphe nuclei. Although stimulation of GABAA receptors in the MR or DR can inhibit serotonergic neurons and reduce extracellular serotonin in the forebrain (Judge et al., 2004; Shim et al., 1997), increases in dopamine metabolism following intra-MR muscimol injections are not affected by serotonin depletion achieved with the serotonin synthesis inhibitor PCPA (Wirtshafter and Trifunovic, 1992). Moreover, increases in locomotion facilitated by intra-MR muscimol injections are not affected by selective lesions of serotonergic cells using 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine (Paris and Lorens, 1987; Wirtshafter et al., 1987). Hence, non-serotonin neurons in the vicinity of the MR appear to be involved in facilitating mesolimbic dopamine transmission, locomotor activity, and possibly reward.

3.4.2. Rostromedial tegmental nucleus

Recently, a new nucleus has been identified and named the rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg) (Jhou et al., 2009b) or the tail of the VTA (Kaufling et al., 2009). The RMTg is located just posterior to the VTA; the posterior end of the VTA overlaps with the anterior part of the RMTg (Fig. 1C). It contains predominantly GABAergic neurons, whose major projections target dopaminergic neurons in the VTA and substantia nigra. Available data suggest that the RMTg may be a key site through which withdrawal-type signals are conveyed over approach-type processes. RMTg neurons are mostly excited by shock-predictive stimuli, and inhibited by sucrose-predictive stimuli (Jhou et al., 2009a). This pattern is the opposite of that reported for putative DA neurons, and similar to that reported for the lateral habenula (Matsumoto and Hikosaka, 2007), which in turn provides a major input to the RMTg. A smaller but still substantial proportion of RMTg neurons are excited by reward omission, again opposite to the pattern of DA neurons and similar to that of the lateral habenula. The RMTg appears to receive afferents conveying withdrawal-type signals from the lateral habenula and the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray whose lesions reduce fear-induced freezing (Kim et al., 1993). The ventrolateral periaqueductal gray receives major inputs from the amygdala (Hopkins and Holstege, 1978). Thus, these findings are consistent with a view that the lateral habenula and RMTg provide inhibitory inputs to dopaminergic neurons in the VTA.

Because GABAergic neurons projecting from the RMTg to the VTA appear to express μ-opioid receptors (Jhou et al., 2009b), we hypothesized that intra-RMTg injections of μ-opioid receptor agonists would be rewarding through the mechanisms that μ-receptor agonists inhibit RMTg neurons exerting tonic inhibition over VTA dopamine neurons, and thereby disinhibit dopaminergic neurons. We found that rats self-administer the μ-opioid receptor agonist endomorphin-1 into the RMTg, but not into the regions dorsal, ventral, or lateral to it (Jhou et al., 2009c). Rats appear to self-administer endomorphin-1 into the RMTg more vigorously than into the VTA filled with dopamine neurons.

3.5. Other trigger zones

There are also additional trigger zones for reward: the septum, lateral hypothalamus and periaqueductal gray. Rats and mice are found to self-administer morphine into the medial and lateral septal area (Cazala et al., 1998; Stein and Olds, 1977). The midline region of the septal complex also supports self-administration of GABAA receptor agonist muscimol (Gavello-Baudy et al., 2008) and AMPA (Shin and Ikemoto, 2008). Opiates appear to be also self-administered into the lateral hypothalamic area (Cazala et al., 1987; Olds, 1979), and periaqueductal gray (David and Cazala, 1994).

4. Defining reward with neurobiological terms: other effects of injection manipulations that mediate self-administration

For the most part, modern biological research has taken reductionist approaches to mechanisms of behavior. For example, experiments examining single brain sites reduce complex biological functional mechanisms into their constituent components. As discussed above in the case of self-stimulation, behavioral neuroscientists have studied psychological functions by lesioning particular brain regions. This approach is useful for examining the function localized within the size of lesions or organized in a serial circuit or unique functions of the region of interest, but not for functions organized over multiple brain regions in a network manner. In other words, this approach provides useful information about parts of more complex systems, but often obscures the function of the whole.

4.1. A neurobiological theory of reward

Here, I will outline a theoretical framework for investigating the neurobiology of reward, which can be considered an extension of the concept general drive (Hebb, 1955), the biological theory of reinforcement (Glickman and Schiff, 1967) and the Seeking system (Panksepp, 1998). This theory is intended to explain the behavioral effects of pharmacological manipulations that were discussed above and will be described below. This theory and associated findings are also of relevance for understanding how the brain works.

Key observation that led to the present theory is that rewarding drug manipulations at regions outside of the VTA–VS dopamine system (e.g., the supramammillary and midbrain raphe nuclei) trigger a set of effects similar to those triggered by manipulations at the VTA–VS dopamine system. The intracranial self-administration studies reviewed above found that the medial VTA–VS dopamine system mediates various drugs’ rewarding effects, while they also show that non-dopaminergic mechanisms in regions outside the VTA and VS are involved in reward. In Sections 4.2–4.4, I will review studies showing that these structures also mediate other effects including induction of conditioned approach, facilitation of ongoing approach and physiological changes consistent with approach. The present theory claims that drug manipulations’ effects triggered from each of these structures arise from the interactions of these structures rather than each mediating them independently. Another important claim of the theory is that these pharmacological manipulations are rewarding because they activate a set of structures that coordinate various selective functions (including perceptual, visceral and reinforcement processes) into a global function of approach. This view is also supported by the fact that rewarding drug manipulations elicit flexible approach in a variety of context (reviewed below).

4.1.1. Evolution and the concepts of approach, reinforcement and reward

Reinforcement is intimately linked with approach and withdrawal because of the way in which evolution has shaped the functional organization of the nervous system (Glickman and Schiff, 1967). In animals ranging from worms to humans, the nervous system’s fundamental function is to guide approach and withdrawal (Schneirla, 1959). Approach, in its most basic form, is forward locomotion, guided by environmental cues, to life-sustaining or promoting stimuli. This basic process is elaborated in the complex nervous systems of species like rats, which have extended perceptual, cognitive and motor processes. Needless to say, these processes are much more elaborate in humans. Approach comes in different forms in rats including the exploratory behaviors of forward locomotion, rearing and sniffing. Indeed, to explain the strong tendency for animals to explore, a number of investigators have proposed an innate process (or drive) for exploration (Berlyne, 1950; Montgomery, 1954; Pavlov, 1927; Tolman, 1925). In this evolutionary light, reinforcement mechanisms are thought to be added onto basic approach and withdrawal mechanisms so that more complex organisms like rats can learn to express elaborate instrumental responses and habits, i.e., conditioned approach and withdrawal. In other words, species-specific approach (including exploration), can be shaped into elaborate instrumental responses and habits by reinforcement processes.

The process of reward can be thought to be homologous to positive affective arousal, which is operationally defined as follows: If an event subsequently leads to conditioned approach, the event must have elicited positive affective arousal (Young, 1959). This retrospective definition was needed, since reward could not be visualized or measured as it occurs. In other words, positive affective arousal leads to positive reinforcement. This notion is parallel to Glickman and Schiff’s (1967) thesis, which claims, in a nutshell, that engaging approach-type behaviors (activation of approach processes) leads to positive reinforcement (conditioned approach). Therefore, in biological terms, positive affective arousal (or reward) may be defined as activation of approach processes.

4.1.2. Modules

The present theory is based on the concept of the module, which is defined as a unit of biological organization from which discrete functions emerge through interactions among its components (Hartwell et al., 1999). Some brain structures participate in multiple modules, and asingle module may be made up of multiple smaller modules (sub-modules). This concept provides a framework for understanding neuronal organization for voluntary behavior controlled by rewards (i.e., approach) and allows investigators to examine mechanisms within modules as well as interactions between modules for adaptive functions.

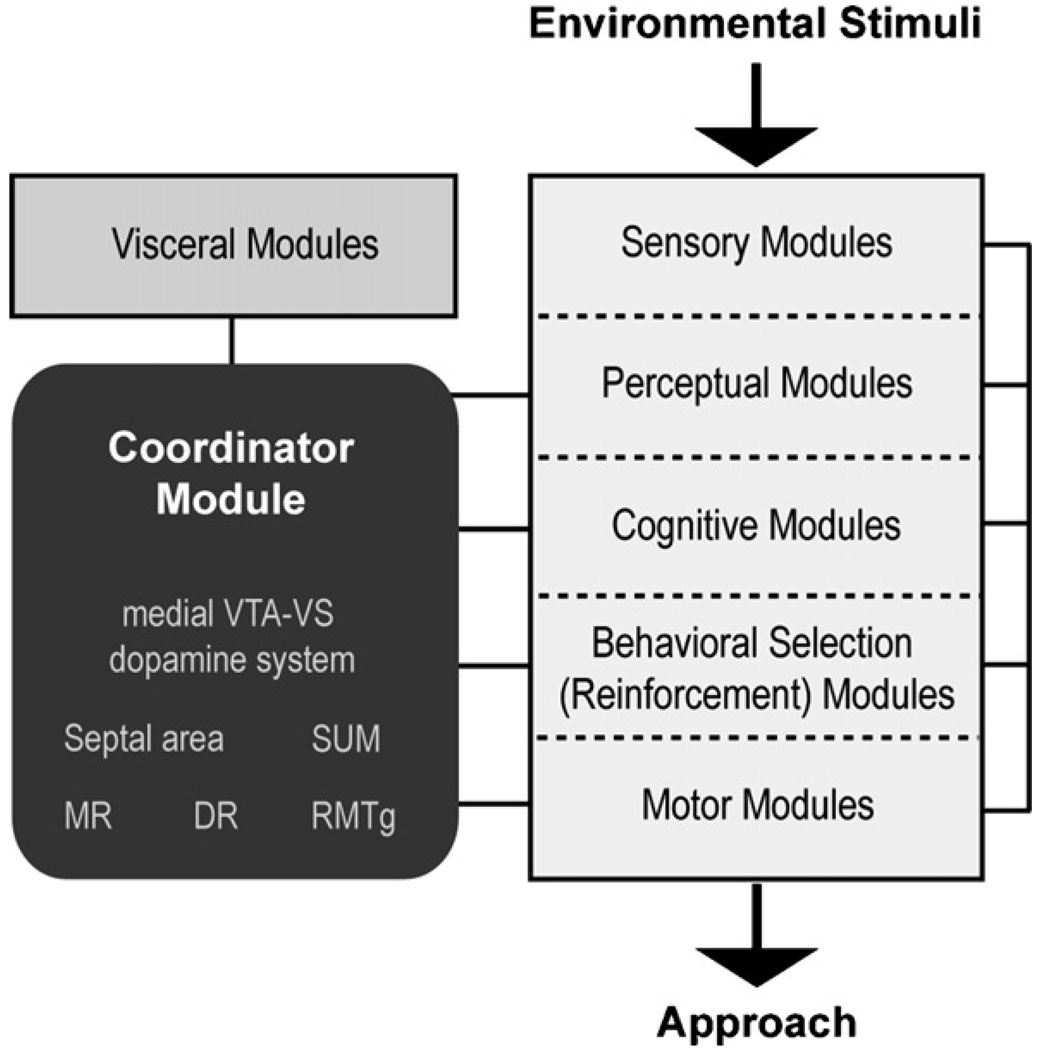

4.1.3. Approach coordinator module

The central nervous system constantly interacts with the environment with respect to approach and withdrawal; therefore, the central nervous system must contain modules (intrinsic neuronal processes) that coordinate various selective functions into global functions of approach and withdrawal. These selective functions include processes involved in perception, motor control, and reinforcement, among others. Psychologists have referred to organizing processes for major purposive behavioral phenomena as motivations or drives (Gallistel, 1975; Hebb, 1949); the module that coordinates approach behavior can be said to process approach motivation or drive. However, because these concepts have been used differently among theorists, to avoid confusion, I will refer to the coordinating process as coordinator for approach. Moreover, while it is more commonly postulated the existence of different drives such as energy balance, sex and novel stimuli, the present theory does not deny the existance of such processes. It postulates a general approach coordinator that work with these specific drives. Fig. 6 schematically depicts the approach coordinator module and its relationship with other modules involved in approach behavior. I will characterize below the role of the approach coordinator module in relation to those of sensory, perceptual, cognitive, behavioral selection and visceral modules. Activities of these modules are organized into adaptive approach, mediated by motor modules.

Fig. 6.

Conceptual scheme involving modules for voluntary behavior controlled by rewards. The affective arousal module interacts with other modules to alter voluntary behavior.

It is not the coordinator module, but sensory and perceptual modules that determine what is worth approaching. Coordinator for approach organizes adaptive approach in response to stimuli that are perceived to be potentially valuable, including nourishments, water, and sex as well as novel stimuli. It may also organize approach for information concerning valuable stimuli (Bromberg-Martin and Hikosaka, 2009) and manipulative stimuli that offer the promise of environmental control including light (see Section 4.3.2). These environmental stimuli are detected and appraised with innately wired mechanisms in some cases and acquired mechanisms in others organized in sensory and perceptual modules assisted also by cognitive modules.

The coordinator module interacts with cognitive modules that process information on the environment, self and action. Cognitive processes include conscious awareness, through which animals integrate past and present, and external and internal information. Although the content of consciousness differ widely in different contexts, heightened activity of the approach coordinator module can be described as a state of being “curious”, “hopeful” or “energized”. In the presence of salient stimuli, this heightened activity may correspond to “wanting”, “desire” or even “craving”. Approach coordinator activity may not fully correlate with “pleasure”, because this experience usually refers to a positive feeling without explicitly implicating its effects on action.

It is important to emphasize that the activation of this module depends on the context. Under natural (non-drug) conditions, this coordinator module is particularly activated when conditions indicate that life-sustaining or promoting stimuli are near (spatially or temporally), but are unclear about what responses will actually procure them. In the laboratory setting, this module is particularly active during early stages (the acquisition) of Pavlovian or instrumental conditioning tasks. Activity level of this coordinating module is minimal in fixed contexts, in which environmental conditions and events are predictable. In addition to being activated before procuring rewards, this module is also activated upon an unexpected encounter with rewards or conditioned stimuli. Consistent with Young’s definition of affective arousal, the approach coordinator is not necessarily triggered in response to a favorite food (e.g., sucrose solution), if there is nothing to be learned. This module is not activated by rewards that are fully predicted by the context, whereas it is activated by rewards or conditioned stimuli that have not been predicted. Similar properties have been found in dopamine neurons localized in the ventral midbrain, as detected by electrophysiological unit recordings (Schultz, 2002). It should be noted that the finding that activation of dopamine neurons upon unpredictable stimuli is associated with the VTA and substantial nigra. In Section 5, I will suggest that the substantia nigra pars compacta are not a component of the approach coordinator module, but behavioral selection modules.

The approach coordinator module may be activated in certain aversive contexts where it is possible that some actions prevent aversive events from occurring. According to the neurobiological theory of reward, the approach coordinator should be actively inhibited by unpredicted, potentially life-threatening stimuli (Ungless et al., 2004) to replace approach with withdrawal, leading to conditioned withdrawal (Liu et al., 2008; Shippenberg et al., 1991). However, when animals actively cope with predictable potential threats to avoid them, this coordinator module may be activated, a process that can be conceived as approach for safety (Ikemoto and Panksepp, 1999).

Although the context determines if the approach coordinator is activated with natural stimuli, this is not true with the drug injection manipulations discussed above. Drug manipulations are artificial, and bypass sensory, perceptual and cognitive modules to directly activate the approach coordinator module. Thus, rewarding injection manipulations activate the coordinator module regardless of predictability or survival value.

The approach coordinator module interacts with reinforcement processes, which utilize perceptual, cognitive and sensory-motor information for selection of adaptive responding. As mentioned above, the activation of approach coordinator leads to reinforcement processes, which shape species specific approach into adaptive conditioned responses and habits. In other words, reinforcement processes may impose inhibitory actions over approach coordinator activity in such a way that initially flexible, variable approach directed by the approach coordinator module becomes more and more fixed and focused, as the level of conditioning increases in highly predictable environments with natural salient stimuli. It should be noted that rewarding drug manipulations would continue to activate flexible approach even after many repeated conditioning sessions, because they bypass sensory/perceptual/cognitive processes to directly activate the coordinator module.

Activity of the approach coordinator module appears to play a major role in the regulation of the organism’s state, which depends on the interaction between the external sensory/perceptual/cognitive modules and the visceral modules, which monitor and control internal conditions. For example, if a rat is sick, it will not be energized by the appetitive stimuli described above. Similarly, if a rat has eaten food minutes ago, stimuli predicting more of the same food will not activate this coordinating module. On the other hand, food restriction would sensitize the approach coordinator module in response to salient stimuli. This sensitized state is not selective to food: animals under food restriction would facilitate responding for other salient stimuli such as novel stimuli (Dashiell, 1925), brain stimulation reward (Brady et al., 1957) and drugs (Carr, 2002). In rats, this coordinator module is thought to be more active during the night than the day (i.e., under circadian control). When the module’s overall activity is down (as in sleep or quiet state), drug manipulations appear to have smaller impacts on modular activity. It has been shown that intravenously delivered amphetamine increase locomotor activity more vigorously in novel environments than the same injection in home environments, even if the two environments consist of identical physical space (Badiani et al., 1995; Crombag et al., 1996). Thus, tonic state of the approach coordinator module or the organism appears to influence the magnitude of drug injection effects.

4.1.4. Structural components of approach coordinator

The VTA–VS dopamine system has already been implicated in reward and motivation (Ikemoto, 2007; Ikemoto and Panksepp, 1999). According to the neurobiological theory of reward, dopamine’s motivational functions arise from its interactions with other components of the approach coordinator module. This theory claims that coordinating process for approach arises from interactions between extended brain structures including the medial VTA–VS dopamine system, septal area, SUM, RMTg, MR and DR, because these regions mediate similar approach related effects of rewarding drug injections. Behavioral and physiological effects of rewarding drug manipulations are discussed below and summarized in Table 1. I will further elaborate structural components of the approach coordinator module in Section 5.

Table 1.

Summary of structures for approach coordinator module and associated effects of injection drug manipulations.

| Structure |

Effects of intracranial injection manipulations |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Receptors | Induction of conditioned approach |

Facilitation of ongoing approach | Facilitation of physiological responses |

|||

| ICSA | CPP | Locomotion | Cue seeking | Stress | Theta | ||

| Medial VS | Dopamine | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Cannabinoid | • | • | • | ||||

| Septum | GABA | • | • | • | |||

| Glutamate | • | • | • | • | |||

| SUM | GABA | • | • | • | |||

| Glutamate | • | • | • | • | |||

| Posterior VTA | Acetylcholine | • | • | • | |||

| Opiate | • | • | • | ||||

| Cannabinoid | • | • | • | ||||

| RMTg | Opiates | • | • | ||||

| MR | GABA | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Glutamate | • | • | • | • | |||

| DR | GABA | • | • | • | • | ||

| Glutamate | • | • | • | ||||

Note: The dot(•) indicates the presence of effect, while a blank indicates the lack of adequate information, not the absence of effect. The table lists a structure only if adequate information is available for at least two categorical effects. Abbreviations: CPP, conditioned place preference; ICSA, intracranial self-administration.

4.2. Conditioned place preference

Place conditioning procedures are used to experimentally detect whether a particular manipulation is reinforcing. In drug-induced place conditioning, one of two compartments is paired with drug administration, while the other is typically paired with vehicle administration. After these pairings, animals are given access to both compartments in the absence of drugs. More time spent in the drug-paired compartment than the vehicle-paired compartment is interpreted as increased approach toward the drug-paired compartment. Therefore, conditioned place preference suggests that drug administration has elicited positive affective arousal (or approach coordinating process), which led to positive associative learning between the drug-induced state and cues in the drug-paired compartment (positive reinforcement).

Positive place conditioning effects were observed following some of the drug manipulations that evoke self-administration as discussed above. These manipulations include cocaine administration into the medial olfactory tubercle (Ikemoto, 2003; Ikemoto and Donahue, 2005), Δ9THC into the medial shell of the accumbens (Zangen et al., 2006), carbachol, endomorphin-1, or Δ9THC into the posterior VTA (Ikemoto and Wise, 2002; Zangen et al., 2002, 2006), AMPA into the SUM (Ikemoto et al., 2004), muscimol or baclofen into the MR or DR (Liu and Ikemoto, 2007; Shin and Ikemoto), and endopmrphin-1 into the RMTg (Jhou et al., 2009c). The fact that these manipulations induce conditioned place preference is consistent with the view that they activate the approach coordinator module, leading to conditioned approach. Because the place conditioning effects of drugs have not been extensively studied with respect to fine anatomy, it would be interesting to conduct mapping work to determine to what extent conditioned place preference effects are co-localized with self-administration effects of the same intracranial injection manipulations.

4.3. Facilitation of ongoing approach

Rewarding manipulations that support instrumental responding appeart of acilitate ongoing approach and seeking. For example, lateral hypothalamic brain stimulation reward, when noncontingently applied, always elicits sniffing in rats (Clarke and Trowill, 1971; Rossi and Panksepp, 1992), even when they are anesthetized (Ikemoto and Panksepp, 1994). Moreover, systemic drug injections that are rewarding typically facilitate locomotor activity (Wise and Bozarth, 1987) in rats. Similarly, rewarding intracranial drug manipulations elicit locomotor activity and more selectively facilitate actions in response to salient stimuli. Thus, these findings are consistent with the view that rewarding manipulations activate coordinating process for approach.

4.3.1. Locomotor activity

According to the theoretical view, rewarding drug manipulations will activate the coordinator module for approach, increasing the levels of approach behaviors. Since activation of the coordinator module elicits environment-appropriate approach, rats in novel chambers would explore the environments, increasing locomotor activity. Indeed, rewarding drug manipulations generally facilitate locomotor activity in open fields (Wise and Bozarth, 1987). The locomotor effects of dopaminergic drugs administered into the VS have been extensively studied. The effective zones within the VS for locomotor effects (Ikemoto, 2002) appear to roughly correspond to effective zones for intracranial self-administration (Ikemoto, 2003; Ikemoto et al., 2005). Similarly, locomotor activity is facilitated by other rewarding manipulations: muscimol or AMPA into the medial septum (Osborne, 1994; Shin and Ikemoto, unpublished observation), picrotoxin injections into the SUM (Shin and Ikemoto, 2010a), carbachol, endomorphin-1, or Δ9THC into the posterior VTA (Ikemoto et al., 2003; Zangen et al., 2002, 2006), and muscimol or baclofen injections into the MR or DR (Fink and Morgenstern, 1986; Przewlocka et al., 1979; Wirtshafter et al., 1993).

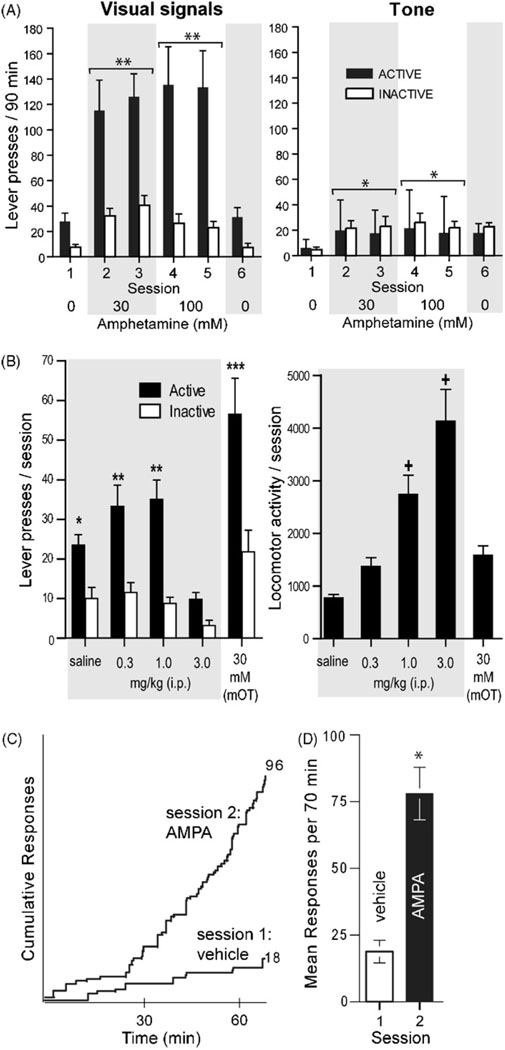

4.3.2. Facilitation of responding rewarded by unconditioned visual signals

It is not always easy to interpret locomotor activity data because locomotor activity does not selectively indicate approach; it may reflect “general” arousal or withdrawal-type responses including escape. Our group has adopted a new procedure to detect effects of intracranial manipulations on approach, using lever pressing rewarded with unconditioned visual stimuli. This procedure is based on the finding that mere presentation of unconditioned visual signals is rewarding in rats and other laboratory animals (Hurwitz, 1956; Kish, 1955, 1966; Marx et al., 1955; Stewart and Hurwitz, 1958). Rats readily learn to respond on a lever to deliver unconditioned visual signals. Increased lever pressing induced by drug injections indicates their effects on approach.

This procedure selectively detects the effects of drug injection manipulations on interaction with salient stimuli (approach), as distinguished from “general” arousal or hyperactivity, which are not approach behaviors. We found that noncontingent amphetamine injections into the medial olfactory tubercle facilitate seeking for visual signals, but not non-salient tones (Shin et al., 2010) (Fig. 7A), suggesting that the stimuli needs to be salient for drugs to increase seeking. Similarly, noncontingent cocaine injections into the medial olfactory tubercle facilitate responding rewarded by unconditioned visual signals (Ikemoto, 2007). Systemic administration of a high dose of amphetamine (3 mg/kg, i.p.) clearly decreases responding for visual signals, and markedly increases locomotor activity (Fig. 7B). In comparison, when the same rats receive intra-tubercle amphetamine, their responding for visual signals is robust, but their locomotor activity is modest. These results suggest that increased approach elicited by visual signals is not a byproduct of hyperactivity or general arousal induced by manipulations.It should be noted that systemic amphetamine appears to activate non-approach type behavioral activities that inhibit or compete with approach coordinating process.

Fig. 7.

Facilitation of responding for unconditioned visual signals by rewarding manipulations. (A) Upon active lever pressing, the visual signal group (N = 8) received an illumination of the cue lamp just above the lever for 1 s and an extinction of the house lamp for 7 s, whereas the tone group (N = 8) received a 1 s tone. Both groups received noncontingent infusions (100 nl per infusion) on a fixed 90-s interval schedule. Lights, but not tone stimuli, support robust lever-pressing in the presence of amphetamine. Data are means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, significantly greater than vehicle values. (B) Rats (N = 13) received systemic injections of vehicle or amphetamine (0.3, 1, and 3 mg/kg, i.p.) just prior to each session, except that in the last session, they received noncontingent intra-tubercle amphetamine (30 mM; 78 nl per infusion). *P < 0.001, significantly greater than its inactive lever presses and the active lever presses of the 3 mg/kg session. **P < 0.005, significantly greater than its inactive lever presses and the active lever presses of the saline session. ***P < 0.0005, significantly greater than its inactive lever presses and the active lever presses of all other sessions. +P < 0.005, significantly greater than the values of the saline, 0.3 mg/kg and intra-tubercle sessions. (C) AMPA administration into the SUM facilitates lever-pressing reinforced by visual signals. Each rat was placed in a test chamber and received noncontingent infusions into the SUM. Infusions (75 nl per infusion) of vehicle and 0.3 mM AMPA were administered on a fixed interval schedule of 70 s (total infusion of 60 over 70 min) in sessions 1 and 2, respectively. Sessions were separated by 24 h. The infusion rate of noncontingent administration of AMPA mimicked the rate of self-administration conducted using a similar procedure (Ikemoto et al., 2004). During these sessions, each lever-press illuminated a cue-light just above the lever for 5 s. The left panel depicts response patterns of a representative rat during sessions. Numbers on the right indicate total numbers of responding. The right panel depicts mean leverpresses (N = 7) with SEM in sessions 1 and 2. *P < 0.01, significantly different from vehicle values.

Additional data suggest that dopaminergic mechanisms in the vicinity of the medial olfactory tubercle are particularly important in facilitating approach for the opportunity to control significant environmental stimuli. This effect of amphetamine was best mediated through the vicinity of the medial olfactory tubercle than other subregions in the striatal complex. Because co-administration of dopamine D1 or D2 receptor antagonists decreased responding for visual signals facilitated by intra-tubercle amphetamine, these results suggest that dopamine is involved in facilitating responding rewarded by visual signals. Interestingly, intra-tubercle amphetamine facilitates responding for either onset or offset of light signals, suggesting that rats seem to be motivated by the control of visual signals rather than light per se; moreover, responding for visual signals does not seem to be attenuated over repeated sessions. This notion that environmental control serves as a reinforcer was previously suggested by Kavanau (1967).

Preliminary data suggest that the ability of drug injections to facilitate responding for visual signals is not limited to dopamine in the VS. In addition to amphetamine and cocaine into the medial olfactory tubercle, we have found similar enhanced lever pressing for unconditioned visual signals when rats received noncontingent administration of AMPA into the SUM (Fig. 7C; Ikemoto, unpublished observation) or the septal area (Shin and Ikemoto, unpublished observation) and baclofen into the MR or DR (Shin, Vollrath-Smith & Ikemoto, unpublished observation). Enhanced seeking for unconditioned visual signals is also found with noncontingent administration of intravenous nicotine (Chaudhri et al., 2006). Although additional experiments are needed to substantiate the findings, these preliminary data are consistent with the theoretical view that rewarding manipulations activate the general approach coordinating process, generating environment-appropriate approach behavior.

4.4. Induced physiological changes

Rewarding injection manipulations trigger physiological changes consistent with the function of approach. These physiological changes may include autonomic effects, characterized as sympathetic arousal, that coordinate bodily activities for approach/seeking. They also include hippocampal theta rhythm (or rhythmic slow activity), which generally accompanies approach (Vanderwolf and Robinson, 1981).

4.4.1. Mild stress-like effects

Activation of the VTA–VS dopamine system leads to physiological responses that resemble those triggered by mild stressors. Electrical brain stimulation at the medial forebrain bundle/VTA is rewarding (Olds, 1962) and triggers dopamine release in the VS (Fiorino et al., 1993; Garris et al., 1999; Cheer et al., 2005; Hernandez et al., 2006). Such presumably rewarding stimulation at these regions appears to increase blood pressure, an effect that is blocked by pretreatment with dopamine antagonists or 6-OHDA (Spring and Winkelmuller, 1975; Tan et al., 1983; Burgess et al., 1993; Cornish and van den Buuse, 1994) . Electrical brain stimulation also increases norepinephrine, epinephrine and glucocorticoid levels in the plasma of rats (Burgess et al., 1993), effects that are characterized as a set of sympathetic arousal responses. These physiological responses may be more readily triggered by the activation of the VTA–VS dopamine system than other dopamine systems, because administration of D1/D2 receptor agonists or cocaine, but not procaine, into the medial VS increases plasma glucocorticoid levels more effectively than the same injections into the medial prefrontal cortex or dorsal striatum (Ikemoto and Goeders, 1998). Moreover, increased blood pressure is also observed after microinjections of the substance P analog DiMe-C7 into the VTA and is abolished by pretreatment with systemic dopamine antagonists (Cornish and van den Buuse, 1995).

Other rewarding injection manipulations may have similar physiological effects; but their effects have not been thoroughly studied. One relevant finding is that the administration of muscimol into the MR increases plasma levels of ACTH and glucocorticoid in rats (Paris et al., 1991). These effects are consistent with the view that rewarding injection manipulations trigger coordinated processes over the entire system consistent with the global function of approach, which requires ready energy.

4.4.2. Recruitment of hippocampal theta rhythm

Hippocampal theta rhythm has been shown to be facilitated by some rewarding injection manipulations. It may not selectively indicate approach, but it does correlate with arousal that is typically accompanied by voluntary movements (Vanderwolf, 1971). GABAA receptor agonists, glutamate receptor antagonists (both AMPA and NMDA receptor types) or serotonin 1A receptor agonists administered into the MR induce hippocampal theta rhythms in urethane-anesthetized rats (Kinney et al., 1994, 1995; Vertes et al., 1994). Similarly, glutamate applied at the SUM facilitates hippocampal theta rhythms (Ariffin et al., 2009), while the inhibition of supramammillary neurons by microinjections of procaine or nicotinic receptor antagonists disrupt hippocampal theta induced by lower brainstem stimulation (Ariffin et al., 2009; Kirk and McNaughton, 1993; Thinschmidt et al., 1995). Hippocampal theta can be facilitated by intra-septum injections of muscimol, AMPA and NMDA (Allen and Crawford, 1984; Bland et al., 2007; Puma and Bizot, 1999). These findings are consistent with the view that rewarding injection manipulations activate a module to coordinate the entire system for approach.

5. Structural components and their organization of reward

Theories are useful when they help to generate testable hypotheses. In light of the neurobiological theory described above, I will discuss specific components of the brain reward circuitry. However, no guidelines exist for defining the structural components of network modules. I will construct structural components of approach coordinator module on the basis of closeness in connectivity with the drug trigger zones discussed above, using tract tracer data. But, proposed structural components need to be tested for validity by future research.

5.1. Structural components

Brain networks’ structural elements can be studied at multiple levels (Sporns et al., 2005). The microscale level addresses connections of single neurons and their synaptic connectivity. This level provides the resolution needed to understand and precisely predict psychobehavioral processes. However,at present, no sufficient data are available to elucidate the organization of the approach coordinator module at this level. It is a daunting, if not impossible, task to realistically simulate the structural features of mammalian approach coordinator module, since its components appear to be located in many brain regions. Ultimate understanding must include not only the circuitry at the microscale level, but also its network’s interaction with molecular mechanisms inside the cell.

However, it is feasible to discuss structural components and their organization of approach coordinator module at the macroscale level, which deals with brain regions and their pathways. Tract tracer studies on the rat brain offer a wealth of data at this level. However, it is much easier to define single neurons than brain regions. There are different ways to delineate brain regions, and even if a region is universally delineated, the region’s connectivity may be topographical, a feature that reflects functional differences. For example, the nucleus accumbens shell appears to have mediolateral topography for its afferent and efferent connections, and this topography is likely responsible for functional differences between the medial and lateral parts of this structure in reward (Ikemoto et al., 2005; Shin et al., 2008). The same holds true for the olfactory tubercle and VTA, as discussed above. Therefore, we must consider the topographic features of connectivity between structures when defining brain regions. Below, I discuss possible structural components of reward at a macroscale level.

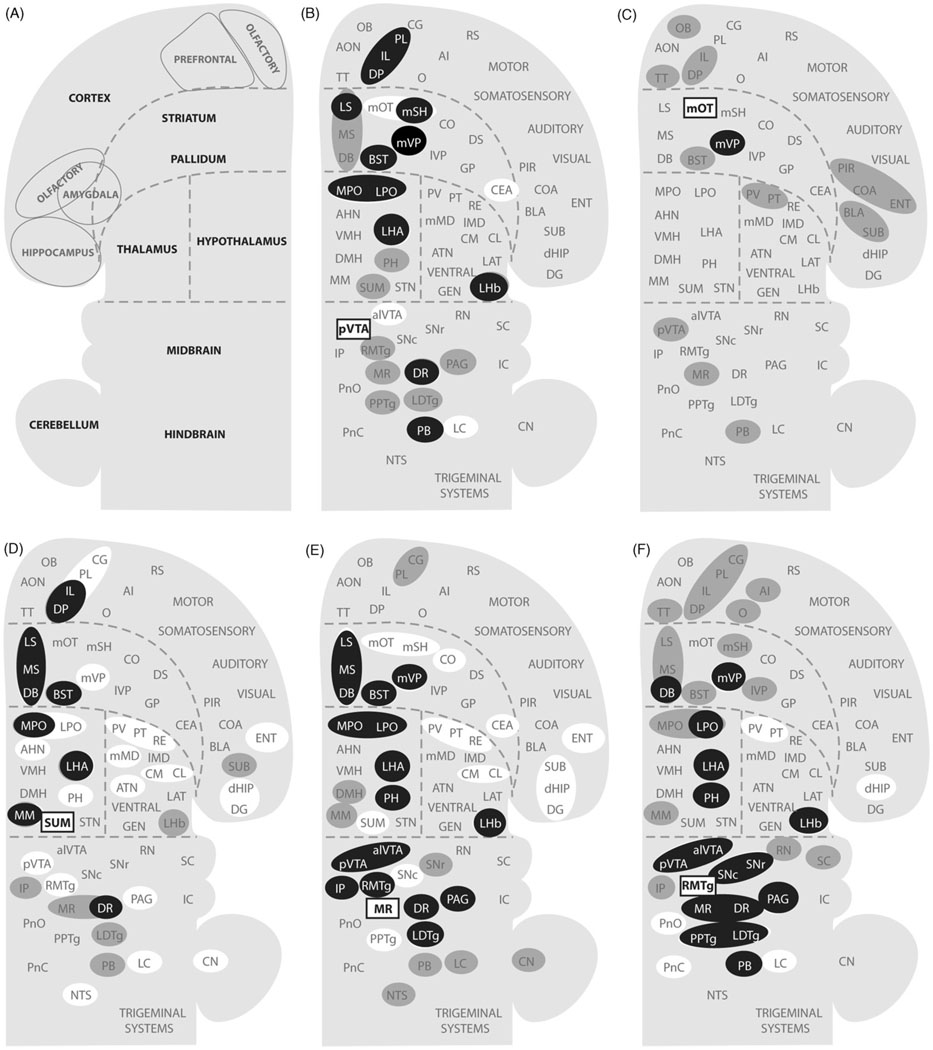

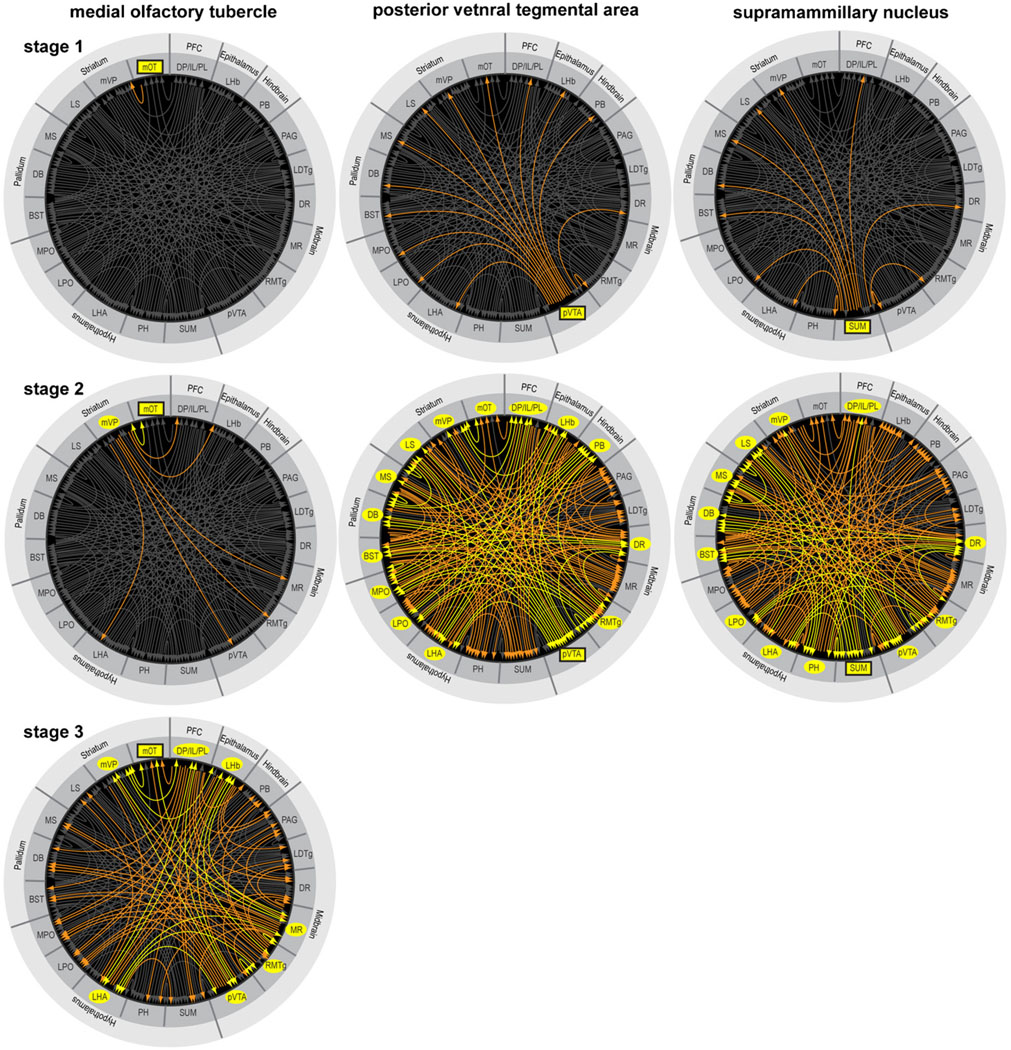

5.1.1. Tract tracer data

Here, I will discuss a procedure used to approximate the components of the approach coordinator module using tract tracer data. I selected 5 structures that are components of brain reward circuitry on the basis of the theoretical perspective that I outlined above (Table 1): the medial VS (medial olfactory tubercle), posterior VTA, SUM, MR and RMTg. Other likely components of the approach coordinator module, the medial shell, septal area and DR, were not included in this analysis because of several grounds. The medial shell’s connectivity is roughly represented by that of the medial olfactory tubercle (Ikemoto, 2007). The septal area is large; yet, drug trigger sensitive zones within the septum have not yet been clearly investigated. The DR’s connectivity is somewhat similar to that of the MR; in addition, the DR is less effective than the MR in mediating drug self-administration.

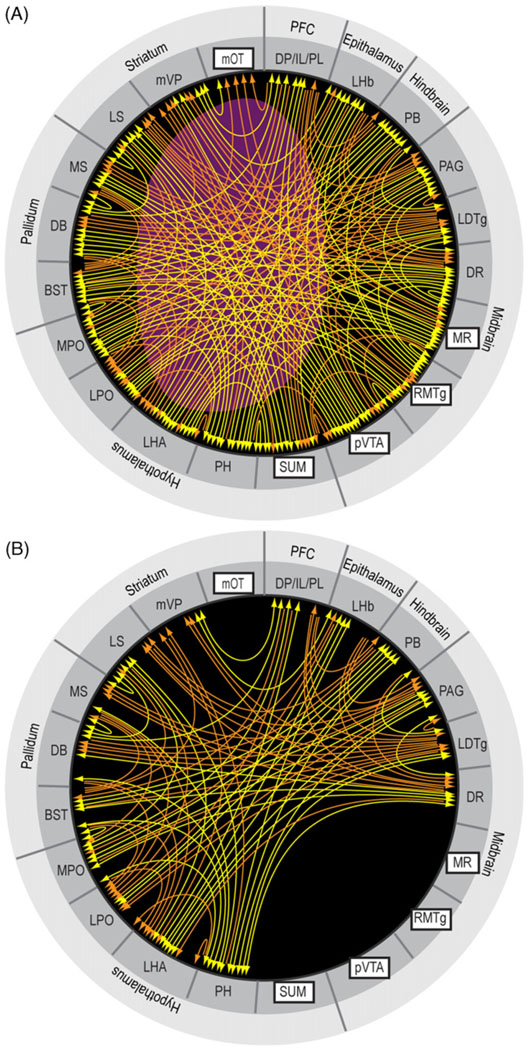

To see how these trigger zones connect with other structures, I consulted previously published studies on the afferents and efferents of these trigger zones and summarized their connectivity (only clear connections) in Fig. 8 (Behzadi et al., 1990; Berendse et al., 1992; Berendse and Groenewegen, 1990; Chiba et al., 2001; Dong and Swanson, 2006a; Ferreira et al., 2008; Geisler and Wise, 2007; Geisler and Zahm, 2005; Gonzalo-Ruiz et al., 1992; Groenewegen et al., 1993; Groenewegen et al., 1987; Hasue and Shammah-Lagnado, 2002; Hayakawa et al., 1993; Heimer et al., 1987; Ikemoto, 2007; Jhou et al., 2009b; Kaufling et al., 2009; Kiss et al., 2002; Luskin and Price, 1983; Marcinkiewicz et al., 1989; Moga et al., 1995; Newman and Winans, 1980; Olmos and Ingram, 1972; Petrovich et al., 1996; Phillipson, 1979a; Saper and Loewy, 1980; Semba and Fibiger, 1992; Sesack et al., 1989; Swanson, 1982; Takagishi and Chiba, 1991; Vertes, 1992, 2004; Vertes et al., 1999; Vertes and Martin, 1988).

Fig. 8.

Afferents to and efferents from the trigger zones. (A) Schematic drawing shows a flat map adopted and modified from the one by Swanson (2004). (B–F) Afferents to the trigger zones, indicated by rectangular boxes, are shown in gray shade, while efferents from the trigger zones are shown in white. Black-filled circles indicate regions that are reciprocally connected with the trigger zones. Abbreviations: AHN, anterior hypothalamic nucleus; AI, agranular insular cortex; alVTA, anterolateral ventral tegmental area; ATN, anterior nuclei, dorsal thalamus; BLA, basolateral amygdalar nucleus; BST, bed nucleus of stria terminalis; CEA, central amygdalar nucleus; CG, cingulate cortex; CL, centrolateral thalamic nucleus; CM, central medial thalamic nucleus; CN, cerebellar nuclei; CO, core of the nucleus accumbens; COA, cortical amygdalar nucleus; DB, diagonal band of Broca; dHIP, dorsal hippocampus; DG, dentate gyrus; DMH, dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus; DP, dorsal peduncular cortex; DR, dorsal raphe nucleus; DS, dorsal striatum; ENT, entorhinal area; GEN, geniculate thalamic nuclei; GP, globus pallidus; IC, inferior colliculus; IL, infralimbic cortex; lMD, intermediodorsal thalamic nucleus; IP, interpeduncular nucleus; lVP, lateral ventral pallidum; LAT, lateral nuclei, dorsal thalamus; LC, locus coeruleus; LDTg, laterodorsal tegmental nucleus; LHA, lateral hypothalamic area; LHb, lateral habenular nucleus; LPO, lateral preoptic area; LS, lateral septal area; MM, medial mammillary nucleus; mMD, medial mediodorsal thalamic nucleus; MPO, medial preoptic area; MR, median raphe nucleus; MS, medial septal area; mSH, medial shell of the nucleus accumbens; mOT, medial olfactory tubercle; mVP, medial ventral pallidum; NTS, nucleus of the solitary tract; O, orbital area; PAG, periaqueductal gray; PB, parabrachical nucleus; PIR, piriform cortex; PH, posterior hypothalamic nucleus; PL, prelimbic cortex; PnC, pontine reticular nucleus, caudal part; PnO, pontine reticular nucleus, oral part; PPTg, pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus; PT, paratenial thalamic nucleus; PV, paraventricular thalamic nucleus; pVTA, posterior ventral tegmental area; RE, reuniens thalamic nucleus; RMTg, reostromedial tegmental nucleus; RN, red nucleus; RS, retrosplenial cortex; SNr, substantia nigra, reticular part; SNc, substantia nigra, compact part; STN, subthalamic nucleus; SUB, subiculum; SUM, SUM; SC, superior colliculus; TT, tenia tecta; VMH, ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus.

These trigger zones appear to share many commonly connected regions. The medial olfactory tubercle is unique in that its efferent is limited to the ventral pallidum, although its afferents arrive from some common structures. Fig. 9 provides an overview of connectivity strength by summarizing commonly connected structures. The level of shade of regions in Fig. 9 suggests the extent to which they are connected with the trigger zones. While connectivity strength alone does not indicate modular membership, I assumed that the stronger the connectivity, more likely the region is a component of a module. Closely connected regions with the trigger zones include the medial prefrontal cortex, basal forebrain (medial and lateral septal nuclei and nucleus of the diagonal band of Broca, bed nucleus of stria terminalis and medial ventral pallidum), medial and lateral preoptic areas, lateral and posterior hypothalamic areas, lateral habenula, DR, periaqueductal gray, laterodorsal tegmental nucleus, and parabrachical nucleus. These brain regions above are selected on the basis that they have at least 6 connection counts in terms of efferent and afferent connections with the trigger zones. The connection count of 5 would add the anterolateral VTA, and the connection count of 4 would add the paraventricular and paratenial thalamic nuclei, medial mammillary nucleus, interpeduncular nucleus, pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus and locus coeruleus. These additional regions with the counts of 5 and 4 may well be components of approach coordinator module; but since we need to draw a line somewhere, I continue discussion here excluding them.

Fig. 9.

Regions that are closely connected with the trigger zones for reward. Shades of gray are darker if the region is connected to multiple trigger zones. See Fig. 8 legend for abbreviations.

I will point out four features of the detected components that would support that the present connectivity procedure is reasonable for approximating modular components. Firstly, all of these regions have been shown to support self-stimulation (Olds and Peretz, 1960; Olds and Olds, 1963; Phillips and Mogenson, 1969; Routtenberg and Malsbury, 1969; Routtenberg and Sloan, 1972) and some support intracranial self-administration (Section 3). Secondly, the septal area and DR, which are trigger zones for reward but not included to construct the connectivity map, emerged as regions of close connectivity with those included as the trigger zones.

Thirdly, this analysis shows that the trigger zones are closely connected to subcortical components of the limbic system (Fig. 9), such as the septal area and lateral hypothalamic area, but less connected with cortical limbic structures such as the amygdala, hippocampus and cingulate. Because the amygdala, hippocampus and cingulate are thought to be important for perceptual and cognitive aspects of emotional processes, this observation supports the conceptual scheme presented in Fig. 6, in which perceptual and cognitive modules are distinguished from the coordinator module.

Finally, this connectivity analysis suggests that the trigger zones including the medial VTA–VS dopamine system are not well-connected with the lateral components of the basal ganglia, particularly the caudate putamen and globus pallidus. The basal ganglia are regarded as core structures processing voluntary movements (Hikosaka, 1991; Mink, 1996). In particular, the dorsal striatum and its closely connected components are thought to play key roles in behavioral selections (Belin et al., 2009; Ikemoto, 2007; Yin and Knowlton, 2006). It should be noted that anatomical links from the medial to the lateral circuits of the basal ganglia have been identified (Haber, 2003). I would suggest that these links can be considered as inter-module links rather than intra-module links. Therefore, the present connectivity analysis appears to be a reasonable method to initially select structural components of approach coordinating module.

5.1.2. c-Fos data

The structural components of reward discussed above should be further validated with functional connectivity analyses, which can be done through several procedures including c-Fos (as a neuronal activation marker), electrophysiological neuronal recordings or fMRI involving multiple regions (see Section 6 for additional discussion on this issue). Currently, c-Fos data are available for functional connectivity analysis.

We recently examined c-Fos expression in brain regions following single administration of the GABAA receptor antagonist picrotoxin into the SUM (Shin and Ikemoto, 2006). As reviewed above (Table 1), stimulation of supramammillary neurons by injections of GABAA receptor antagonists or AMPA appears to activate approach coordinator, since they are self-administered (Fig. 5), induce conditioned place preference and facilitate seeking for unconditioned visual signals (Fig. 6C and D) and theta rhythm. We found that a single injection of picrotoxin into the SUM facilitated locomotor activity in an open field, an effect predicted from its role in approach coordinating process. We also found increased c-Fos expression in many brain regions, including the medial prefrontal cortex, medial shell of the nucleus accumbens, septal area, preoptic area, lateral hypothalamic area, posterior VTA, and DR. These regions were also detected by the connectivity analysis above. The c-Fos counts of these regions positively correlated with locomotor activity counts. Thus, an approach coordinating manipulation of intra-SUM picrotoxin appears to activate many of the brain regions detected by the connectivity analysis (Fig. 8 and Fig. 9), suggesting that these regions are functionally linked with the SUM.