INTRODUCTION

Teaching consultation skills in general practice has always been a challenge. A particular area that doctors in training consistently seem to struggle with is in regularly completing high quality consultations in 10 minutes.

It has always been important that a GP Registrar at the end of their training year can consult at 10-minute intervals. Ten minutes is the mean rate of consultation most practices will expect a locum, salaried doctor or new partner to consult at and is the fundamental tool of a GP's trade.

The 10-minute consultation has however become more important to work to under the nMRCGP as the tasks in the Clinical Skills Assessment (CSA) must be completed within 10 minutes. ‘Shows poor time management’ is a reason a candidate can be failed at a CSA station. The CSA will be stopped after 10 minutes and, if candidates have not worked through the full consultation process in this time, marks are lost and this very expensive assessment can be failed.

This article describes a new model to help trainers lead their trainees towards this 10-minute goal which is now so vital for them to achieve before the CSA is sat in their ST3 year.

HOW DO WE TEACH NOW AND WHAT NEEDS TO CHANGE?

Trainers generally allow their GP registrars longer consultation times at the start of their GP training year while they learn, explore, and experiment with long-standing concepts such as establishing rapport, noting opening gambits, hidden cues, the golden 60 seconds at the start of the consultation of not interrupting, eliciting ideas, concerns, expectations, summarising, handing over, checking understanding, safety netting, patient involvement in decisions and choices, and other tasks described in the now standard consultation texts of Roger Neighbour,1 Pendleton,2 Stott and Davies,3 Calgary-Cambridge,4 and others.

The old summative assessment videos and RCGP video could be passed by identifying and demonstrating these objectives in a clear and explicit fashion, which at times could be a little formulaic.

Under nMRCGP5 these consultation skills are now demonstrated as part of the Work Based Practice Assessment (WBPA) in the form of the Clinical Observation Tool (COT). A minimum of 12 of these must be completed in the ST3 year and assessed using the marking grid in the learner's e-portfolio.

This marking grid is identical to the old MRCGP video marking grid, but the advantage of the new system over the old is that not all competencies have to be demonstrated in every COT, but rather over the series of 12 COTs.

Most COTs in practice will be completed as a result of either a joint consultation, joint visit or video analysis between trainer and ST3. The assessment time for each COT is not limited so ST3s can spend as long as they wish on any particular competency to demonstrate proficiency.

Many trainers who have used a basic Pendleton or MRCGP consultation grid to mark and demonstrate consultation competencies will be aware of the tendency of the inexperienced consulter to ‘sawtooth’ through the consultation, constantly allowing the consultation to double back on itself to tasks which could or should have been completed already. This leads to disjointed, prolonged and often unsatisfactory consultations in which the doctor may feel they have lost control.

When a learner establishes in their mind the logical progression of the consultation process we start seeing highly professional, competent, rewarding and skilful consultations.

Under the old MRCGP process, ‘good’ consultation videos were chosen and submitted so, in effect, the trainee was presenting their ‘greatest hits’ consultations rather than an example of everyday practice.

The introduction by the RCGP of the Clinical Skills Assessments is a potentially powerful tool of observing what ST3 do on a day-to-day basis, and cases selected seem to reflect a cross section of presentations in a typical surgery. The CSA consists of 13 consultations so in effect appears designed to mirror a typical surgery.

The ST3 must now, therefore, be prepared by their trainer to demonstrate practical competency in consultation skills consistently over a 2-hour period of 10-minute consultations so a new, perhaps more focused, consultation model which assimilates and incorporates the best of all previous models may be required.

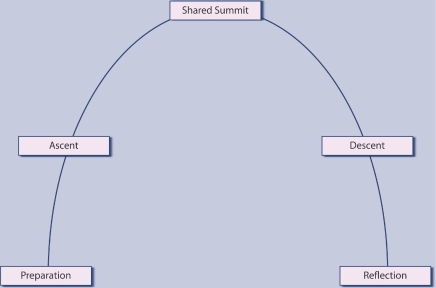

To this end I have devised the three dimensional ‘consultation hill’ as a template to construct the consultation process around. It is merely an alternative way to view the natural process of the consultation but if used, may give the doctor more understanding and perhaps judicious control of the natural flow of the consultation.

THE CONSULTATION HILL

Rather like Roger Neighbour,1 I have identified five stages of the consultation process.

Preparation (base camp)

Ascent

Shared Summit

Descent

Reflection.

A convenient pneumonic for ST3s preparing for the CSA is thus ‘PASS DR’(Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The consultation hill.

Stage 1 — Preparation

Before the ascent of any peak, a good, safe, and competent climber prepares well.

System preparation. Perhaps not too relevant for the CSA, but encompasses ensuring adequate patient access via phone or booking systems, helpful and professional reception staff, adequate waiting room and toilet facilities, good IT systems in place, all forms and equipment that may be needed are to hand, clean and organised consultation room, access to patient information leaflets or handouts, telephone interruptions policy … the list is long.

Personal preparation. This is the stage before the patient enters the room. Roger Neighbour labels this as ‘housekeeping’.1 Be rested, mentally and physically prepared for each consultation. If running late, remember not to rush the patient. If you need to visit the loo, do so now.

Do not allow ‘baggage’ from a previous consultation, event or encounter to prejudice your attitude. Identify personal stresses and prejudices, have systems in place to deal with these and leave them outside the clinical encounter.

Give each patient a fair hearing and chance to contribute to a satisfactory consultation and outcome.

This is really remembering professionalism.

Stage 2 – The Ascent

This is the process defined by the RCGP COT analysis of discovering the reason for the patient's attendance and defining the clinical problem. In the Calgary–Cambridge Model4 it is described as ‘information gathering’ and incorporates Pendleton's concepts2 of eliciting the patients Ideas, Concerns, Expectations. Why here? Why now? During this process, the doctor needs to establish rapport, Neighbour's task of ‘connecting’,1 and must move towards a shared understanding of the problem.

This part of the process incorporates a full history and relevant examination.

By its nature the ascent will be largely patient led. The doctor's role is mainly of listening, facilitating, encouraging, interpreting, clarifying, and empathising. Although often thought of as passive tasks, a competent doctor is active in these passive processes.

Before reaching the summit, it may be useful to ‘summarise’ for the patient. If this summary is agreed, you are at the shared summit. If at this stage the reason for attendance remains unclear, or doctor and patient do not share the same understanding of the patient's reasons for attendance, then perhaps the wrong summit has been reached and the doctor may need to review the ascent and perhaps try a different route.

By the end of this stage the doctor should be establishing a working diagnosis or action plan.

If the doctor fails to identify correctly that a shared summit has been reached, then they may descend the hill and complete the consultation, but the wrong hill may have been climbed or the hill may have only been partially climbed, and the patient's needs neither identified nor addressed.

3. A Shared Summit

Rather like at the top of a hill, the doctor and patient should pause, take in the air, reflect on the ascent and enjoy the view of a shared understanding. This point should be identified and acknowledged.

The patient to some extent can relax as the bulk of their task for the consultation is now done. The doctor, however, cannot relax.

The summit of any peak is a potentially dangerous place where you are often most exposed, so the doctor must be preparing for a safe and timely descent. The descent is led and guided by the doctor in contrast to the ascent, which is patient led, although partly guided by the doctor.

At this point in the consultation the doctor should have reached a working diagnosis or established a management plan. They need to have devised a route whereby to negotiate and hand this over to the patient using information they have acquired on the ascent.

In the context of completing a successful CSA station or 10-minute consultation, the correct shared summit should usually be reached, identified, and agreed within 7–8 minutes and doctors in training need to recognise this point and practice reaching it in the desired time frame.

The brief transition from shared summit to decent is a crucial moment in time in the consultation process. It may be punctuated or accentuated by the doctor using any of a series of deliberate non-verbal communication skills. These may include a pause, a slow intake of breath, a reflective look, a shift in body posture or a change of tone, volume, or rate of speech. These are skills that can and should be practiced and honed. Their deliberate nature allows the doctor to overtly assert that they are now taking more directive control of the remainder of the consultation.

4. The Descent

This is what Neighbour describes as ‘handing over’.1 A tailored explanation of the problem is given and a proposed solution offered, incorporating and using the patients already established health beliefs and understanding. Some of these may be sensitively modified at this stage. The doctor must use language and details of explanations appropriate to the patient at this stage.

A management plan is proposed and approval sought from the patient that this is acceptable and manageable to them.

Compliance with any management plan (be it lifestyle/health-seeking behaviour modification, following advice or a course of medication) is dependant on the patient having understanding, agreement, and a shared ownership with that plan. The doctor should at this point confirm the patient's understanding and define their responsibility and involvement in the process.

Some descents are rapid, safe and straightforward but on other occasions the route may be more challenging. The patient may require more detailed explanations or may question the proposed descent so the doctor should not have a closed mind to the route of descent and be open to some negotiation even at this point.

If the process does not feel smooth and comfortable then the doctor should question whether the wrong shared summit may have been reached, or the route taken thus far may not have been the best one. Perhaps the only outcome of the consultation is to agree this and perhaps plan another assault on the consultation hill on another occasion.

The foot hills of the descent include ‘safety netting’. An agreed follow-up or review date is set and possible outcomes/prognosis discussed so the patient can be helped to identify if further help is needed and, if so, how and when to access this.

5. Reflection

There are always lessons to be learnt from any clinical encounter. Patients' Unmet Needs and Doctors' Educational Needs6 may be identified. Things could always have gone better or been done differently and only by acknowledging this can doctors in training be prepared for a lifetime of self-directed continual professional development.

Doctors need to reflect upon how their work affects their physical, mental, spiritual, and emotional state as healthy doctors are more likely to provide good medical care.

SUMMARY

To prepare for the CSA of nMRCGP, doctors in training must be able to consult competently using 10-minute appointments. This model may help some achieve that goal.

Older GPs may recognise the consultation hill rather more as a voyage over a range of mountains with each peak and summit a challenge in itself.

Prepare well, be fit, be well equipped, have a plan, make the journey in partnership with each patient, enjoy the thrill of the challenge, ensure both return safely, and always strive to make the next trip more successful.

REFERENCES

- 1.Neighbour R. The Inner Consultation: how to develop an effective and intuitive consulting style. 2nd edn. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pendleton D, Schofield T, Tate P, Havelock P. The consultation: an approach to learning and teaching. Oxford: OUP; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stott NCH, Davis RH. The exceptional potential in each primary care consultation. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1979;29(201):201–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverman JD, Kurtz SM, Draper J. Skills for communicating with patients. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.RCGP Curriculum and Assessment Site. MRCGP. http://www.rcgp-curriculum.org.uk/nmrcgp.aspx (accessed 10 Jun 2010)

- 6.Eve R. PUNs and DENs: discovering learning needs in general practice. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]