Abstract

Background

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) constitute a substantial burden to healthcare services. Analysis of national healthcare datasets offers the possibility to advance understanding about the changing epidemiology of COPD.

Aim

To investigate the epidemiology of physician-diagnosed COPD in general practice.

Design of study

Cross-sectional study.

Settings

A total of 422 general practices in England contributing to the QRESEARCH database.

Method

Data were extracted on 2.8 million patients, including age, sex, socioeconomic status, and geographical area. Trends over time for recorded physician diagnosis of COPD were analysed (2001–2005).

Results

There was little change over time in the incidence rate of COPD (2005: 2.0 per 1000 patient-years, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.0 to 2.1), but a significant increase in lifetime prevalence rate (2001: 13.5 per 1000 patients [95% CI = 13.4 to 13.7]; 2005: 16.8 [95% CI = 16.7 to 17.0]; P<0.001). In 2005, 51 804 individuals or one in 59 people in England were recorded with physician-diagnosed COPD. The most deprived people (31.1 per 1000 patients; 95% CI = 30.6 to 31.7) and those living in the north east of England (29.2 per 1000 patients; 95% CI = 28.4 to 30.1) had the highest prevalence. The observed reduction in the rate of smoking by patients with COPD (overall decrease: 2.5%; P<0.001) varied according to socioeconomic group (most affluent: 6.5% decrease, most deprived: 1.3% decrease).

Conclusion

Given the peak in the incidence rate of COPD, we may be approaching the summit of COPD incidence and prevalence in England. However, the number of people affected remains high and poses a major challenge for health services, particularly those in the north east of the country and in the most deprived communities in England. The very limited decrease in smoking rates among the more deprived groups of patients with COPD is also a cause for concern.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, epidemiology, general practice, QRESEARCH, socioeconomic status

INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is now ranked by the World Health Organization as one of the most prevalent long-term conditions in the world.1 The global burden of COPD is predicted to rise, particularly in developing countries, because of the combination of ageing populations and increased smoking rates.2,3 Although a steadily rising prevalence of physician-diagnosed COPD was found among women in the UK between 1990 and 1997, the prevalence among men reached a plateau. It was hypothesised that this sex disparity resulted from the rising prevalence of smoking among women in the 1980s and 1990s and the longstanding plateau in smoking cessation among men.4

The prevention of smoking and the promotion of smoking cessation services are the main strategies to prevent the occurrence and reduce the burden of COPD. In this vein, it is likely that the 2004 Public Service Agreement in England objectives of reducing overall adult smoking rates from 26% to 21% or less by 20105 are likely to be surpassed.6 However, it is unclear whether, in routine and manual workers, in whom smoking prevalence is considerably higher, the more ambitious targets to reduce prevalence will be achieved.

This study of national trends in the epidemiology of COPD was commissioned by the Chief Medical Officer for England because of growing concern about the high prevalence, disease burden, and healthcare costs (£800 million/€936 million annually) associated with COPD (and other respiratory disorders), and is being used to inform policy deliberations on respiratory service provision in England.7

METHOD

Version 10 of the QRESEARCH database was used for this analysis. This database contains representative anonymised aggregated health data derived from 422 general practices throughout England. Although these practices are self-selected, they are broadly representative of primary care practices in the UK.8 Data for this analysis were available for the period 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2005. Data were extracted for the period 1 January 2001 (2 885 724 patients) to 31 December 2005 (2 968 495 patients). The same practices were used throughout the study period. The methods used to collect primary care data for the QRESEARCH database have been previously described.9–12

In the UK, the majority of individuals resident (including children) are registered with primary care, which is free at the point of contact. Patients were included if they were registered on the first day of each year (for example, 1 January 2001) and were registered for the preceding 12 months. Those with incomplete data, that is, temporary residents, newly registered patients, and those who joined, left, or died during each study year were excluded. Patients were considered to have physician-diagnosed COPD if they had a relevant computer-recorded diagnostic Read Code (Box 1) in their electronic health record during the time period of interest.

Box 1. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Read Codes used in these analyses.

| Read Code | Read term |

|---|---|

| H3… | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| H31.. | Chronic bronchitis |

| H310 | Simple chronic bronchitis |

| H3100 | Chronic catarrhal bronchitis |

| H310z | Simple chronic bronchitis NOS |

| H311. | Mucopurulent chronic bronchitis |

| H3110 | Purulent chronic bronchitis |

| H3111 | Fetid chronic bronchitis |

| H311z | Mucopurulent chronic bronchitis NOS |

| H312. | Obstructive chronic bronchitis |

| H3120 | Chronic asthmatic bronchitis |

| H3210-1 | Chronic wheezy bronchitis |

| H3121 | Emphysematous bronchitis |

| H3122 | Acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive airways disease |

| H3123 | Bronchiolitis obliterans |

| H312z | Obstructive chronic bronchitis NOS |

| H313. | Mixed simple and mucopurulent chronic bronchitis |

| H31y. | Other chronic bronchitis |

| H31y1 | Chronic tracheobronchitis |

| H31yz | Other chronic bronchitis NOS |

| H31z. | Chronic bronchitis NOS |

| H32.. | Emphysema |

| H320. | Chronic bullous emphysema |

| H3200 | Segmental bullous emphysema |

| H3201 | Zonal bullous emphysema |

| H3202 | Giant bullous emphysema |

| H3203 | Bullous emphysema with collapse |

| H3203-1 | Tension pneumatocoele |

| H320z. | Chronic bullous emphysema NOS |

| H321. | Panlobular emphysema |

| H322. | Centrilobular emphysema |

| H32y. | Other emphysema |

| H32y0 | Acute vesicular emphysema |

| H32y1 | Atrophic (senile) emphysema |

| H32y2 | Acute interstitial emphysema |

| H32yz | MacLeod’s unilateral emphysema |

| H32yz-1 | Other emphysema NOS |

| H32z.. | Sawyer–Jones syndrome |

| H36.. | Emphysema NOS |

| H37.. | Mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| H38.. | Moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| H3y.. | Severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| H3y-1 | Other specified chronic obstructive airways disease |

| H3y0 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with acute lower respiratory infection |

| H3y1 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with acute exacerbation, unspecified |

| H3z.. | Chronic obstructive airways disease NOS |

NOS = not otherwise specified.

Incidence rate was defined as the number of patients with a new case of physician-diagnosed COPD in a specific year, with the denominator being the number of patient-years of observation (calculated from the number of patients who were registered with practices for the entire year). Lifetime prevalence was defined as the proportion of people with COPD ever diagnosed by a physician, recorded (that is, on at least one occasion) in the GP records prior to the end of each study year (for example, before 31 December 2001); the denominator used to calculate the lifetime prevalence was the number of patients registered with the study practices at the end of each study year (for example, 31 December 2001). Smokers were defined as the proportion of patients with physician-diagnosed COPD and a smoking status code (Read Code: 137 and below) in the last 5 years recorded as a current smoker (in the year of study). Consultation rates (for any reason) per person per year were calculated. These included consultation with a GP or nurse in the home, at the surgery, and/or on the telephone.

How this fits in

In England, there is growing concern that the disease burden and healthcare costs associated with chronic obstructive disease (COPD) will continue to rise. This study found a large rise in the lifetime prevalence of physician-diagnosed COPD between 2001 and 2005, but a peak in the incidence rate. Although we may be approaching the peak of the COPD incidence and prevalence in England, the number of people affected remains high and poses a major challenge for health services, particularly those in the north east of the country and in the most deprived communities in England where high rates of COPD exist. The very limited decrease in smoking rates among the more deprived groups of patients with COPD is also a cause for concern.

Socioeconomic deprivation was defined on the basis of the Townsend score associated with the output area of the patient’s postcode. The Townsend score is a composite score based on unemployment, overcrowding, lack of car, and non-owner occupancy. Higher scores indicate greater levels of socioeconomic deprivation. The cut-offs for the quintiles are based on the national distribution of Townsend scores derived from the 2001 Census.

Statistical methods

Because of known age and sex variations, rates of disease were standardised by sex and 5-year age bands. The mid-year population estimates for England in each year of study were used as the reference population and to estimate the actual number of people with COPD in England.13 The χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables in different groups of patients. The Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test was used to investigate trends over time, this analysis was undertaken using EpiInfo2000 (World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland). Where appropriate, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported.

RESULTS

In 2001, 40 545 patients had a physician diagnosis of COPD. In 2005, this had increased to 51 804 patients.

Trends in incidence rate

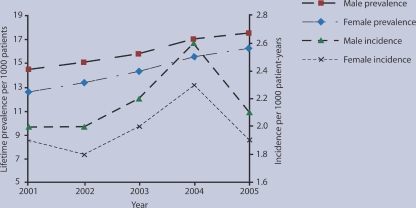

Between 2001 and 2005, there was no significant change in the overall incidence rate of COPD in England (2001: 2.0 per 1000 patient-years [95% CI = 1.9 to 2.0]; 2005: 2.0 per 1000 patient-years [95% CI = 2.0 to 2.1]). Sex-specific incidence rates are detailed in Figure 1 and Table 1. It is of note that a relatively large increase in incidence rate of physician-diagnosed COPD for men and women took place in 2004 before returning to near 2001 levels by the end of the study period.

Figure 1.

Physician-diagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 1.

Incidence rate of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

| Year | Total patients | Patients with COPD | Crude rate per 1000 patient-years | Age–sex-standardised rate patient-years rate per 1000 (95% CI) | Relative % change in standardised rate (from 2001) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | |||||

| 2001 | 1 444 314 | 2 904 | 2.0 | 1.9 (1.9 to 2.0) | N/A |

| 2002 | 1 454 521 | 2 707 | 1.9 | 1.8 (1.7 to 1.9) | –0.1 |

| 2003 | 1 467 867 | 3 014 | 2.1 | 2.0 (1.9 to 2.1) | 0.1 |

| 2004 | 1 466 942 | 3 549 | 2.4 | 2.3 (2.3 to 2.4) | 0.4 |

| 2005 | 1 485 738 | 2 981 | 2.0 | 1.9 (1.9 to 2.0) | 0.0 |

| Males | |||||

| 2001 | 1 441 410 | 3 033 | 2.1 | 2.0 (2.0 to 2.1) | N/A |

| 2002 | 1 451 814 | 3 020 | 2.1 | 2.0 (1.9 to 2.1) | 0.0 |

| 2003 | 1 464 853 | 3 245 | 2.2 | 2.2 (2.1 to 2.2) | 0.2 |

| 2004 | 1 463 393 | 3 900 | 2.7 | 2.6 (2.5 to 2.7) | 0.6 |

| 2005 | 1 482 757 | 3 302 | 2.2 | 2.1 (2.1 to 2.2) | 0.1 |

N/A = not applicable.

Trends in lifetime prevalence

Overall, the recorded lifetime prevalence of COPD increased from 13.5 per 1000 patients (95% CI = 13.4 to 13.7) in 2001 to 16.8 per 1000 patients (95% CI = 16.7 to 17.0) in 2005: a 3.3% rise (P<0.001). The recorded lifetime prevalence by sex can be seen in Figure 1 and Table 2; these data demonstrate significant increases over time in males and females (P<0.001).

Table 2.

Lifetime prevalence rate of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

| Year | Total patients | Patients with COPD | Crude rate per 1000 patients | Age-sex standardised rate per 1000 patients (95% CI) | Change in standardised rate (from 2001) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | |||||

| 2001 | 1 444 314 | 19 025 | 13.2 | 12.6 (12.5 to 12.8) | N/A |

| 2002 | 1 454 521 | 20 343 | 14.0 | 13.4 (13.2 to 13.6) | 0.8 |

| 2003 | 1 467 867 | 21 797 | 14.9 | 14.3 (14.1 to 14.5) | 1.7 |

| 2004 | 1 466 942 | 23 618 | 16.1 | 15.5 (15.3 to 15.7) | 2.9 |

| 2005 | 1 485 738 | 24 889 | 16.8 | 16.2 (16.0 to 16.4) | 3.6 |

| Males | |||||

| 2001 | 1 441 410 | 21 520 | 15.2 | 14.5 (14.3 to 14.7) | N/A |

| 2002 | 1 451 814 | 22 666 | 15.8 | 15.1 (14.9 to 15.3) | 0.6 |

| 2003 | 1 464 853 | 23 901 | 16.5 | 15.8 (15.6 to 16.0) | 1.3 |

| 2004 | 1 463 393 | 25 643 | 17.6 | 17.0 (16.8 to 17.2) | 2.5 |

| 2005 | 1 482 757 | 26 915 | 18.3 | 17.5 (17.3 to 17.7) | 3.0 |

N/A = not applicable.

Geographical and socioeconomic variations in prevalence

There were large differences in the prevalence of COPD between regions within England. For example, the highest age-standardised prevalence of COPD was observed in the north east of the country, which was over twice that observed in the south east (Table 3). There were also substantial socioeconomic differences found, with the most socioeconomically deprived having three times the COPD prevalence rate of the most affluent patients (Table 4).

Table 3.

Lifetime prevalence rate of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) by Government Office region.

| Government Office region | Total patients | Patients with COPD | Crude rate per 1000 patients | Age-sex standardised 1000 patients (95% CI) | Change in standardised rate (from 2001) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | |||||

| North East | 156 875 | 3 469 | 22.1 | 22.2 (21.5 to 22.9) | N/A |

| North West | 255 253 | 5 323 | 20.9 | 21.1 (20.6 to 21.7) | N/A |

| Yorkshire and Humberside | 326 791 | 6 337 | 19.4 | 18.1 (17.7 to 18.6) | N/A |

| South West | 389 147 | 5 172 | 13.3 | 12.8 (12.5 to 13.2) | N/A |

| West Midlands | 222 635 | 3 256 | 14.6 | 12.5 (12.0 to 12.9) | N/A |

| East Midlands | 421 898 | 4 981 | 11.8 | 11.3 (11.0 to 11.6) | N/A |

| East of England | 269 505 | 3 062 | 11.4 | 11.1 (10.7 to 11.5) | N/A |

| London | 344 755 | 3 993 | 11.6 | 11.8 (11.4 to 12.1) | N/A |

| South East | 478 086 | 4 952 | 10.4 | 10.3 (10.0 to 10.6) | N/A |

| 2005 | |||||

| North East | 164 875 | 4 687 | 28.4 | 29.2 (28.3 to 30.1) | 7.0 |

| North West | 267 032 | 6 384 | 23.9 | 24.5 (23.9 to 25.1) | 3.4 |

| Yorkshire and Humberside | 342 439 | 7 626 | 22.3 | 20.1 (20.4 to 21.3) | 2.0 |

| South West | 402 309 | 6 643 | 16.5 | 15.9 (15.6 to 16.3) | 3.1 |

| West Midlands | 228 175 | 4 274 | 18.7 | 15.8 (15.3 to 16.3) | 3.3 |

| East Midlands | 427 556 | 6 842 | 16.0 | 15.4 (15.0 to 15.7) | 4.1 |

| East of England | 275 496 | 4 044 | 14.7 | 14.3 (13.9 to 14.8) | 3.2 |

| London | 360 513 | 4 804 | 13.3 | 14.1 (13.7 to 14.5) | 2.3 |

| South East | 489 971 | 6 500 | 13.3 | 13.1 (12.8 to 13.4) | 2.8 |

N/A = not applicable.

Table 4.

Lifetime prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) by socioeconomic status (quintile of Townsend score).

| Year and Townsend quintile | Total patients | Patients with COPD | Crude % | Age–sex-standardised % (95% CI) | Change in standardised rate (from 2001) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | |||||

| 1 (most affluent) | 634 434 | 5 828 | 9.2 | 8.3 (8.1 to 8.5) | N/A |

| 2 | 565 812 | 6 141 | 10.9 | 9.8 (9.5 to 10.0) | N/A |

| 3 | 536 218 | 7 232 | 13.5 | 12.4 (12.1 to 12.7) | N/A |

| 4 | 497 925 | 8 588 | 17.3 | 17.2 (16.9 to 17.6) | N/A |

| 5 (most deprived) | 535 216 | 11 705 | 21.9 | 24.8 (24.4 to 25.3) | N/A |

| 2005 | |||||

| 1 (most affluent) | 648 634 | 7 861 | 12.1 | 10.2 (10.0 to 10.5) | 1.9 |

| 2 | 580 431 | 8 084 | 13.9 | 12.1 (11.8 to 12.4) | 2.3 |

| 3 | 552 702 | 9 664 | 17.5 | 16.2 (15.8 to 16.5) | 3.8 |

| 4 | 515 271 | 10 784 | 20.9 | 22.0 (21.6 to 22.5) | 4.8 |

| 5 (most deprived) | 567 835 | 14 219 | 25.0 | 31.1 (30.6 to 31.7) | 6.3 |

N/A = not applicable.

National estimate of numbers of patients with COPD

It was estimated that 842 100 (95% CI = 834 800 to 849 400) of 50 million people in England were diagnosed with COPD in 2005; this translates into approximately one person in 59 receiving a diagnosis of COPD at some point in their lives. In the most socioeconomically deprived quintile, one in 32 patients were diagnosed with COPD, compared with one in 98 patients in the most affluent quintile.

Consultation rates

In 2005, patients with COPD had the highest yearly rate of GP and nurse consultations when compared with other groups of patients with respiratory diseases (after standardising for age and regardless of the reason for the encounter; Table 5.

Table 5.

Consultation rates with GPs and nurses for any reason by patients’respiratory conditions in 2005.

| Disease | Total consultations | Disease patients | Crude rate per person | Age–sex-standardised rate per person (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 571 922 | 51 804 | 11.0 | 7.9 (7.8 to 8.0) |

| Asthma | 2 012 681 | 333 294 | 6.0 | 6.4 (6.4 to 6.5) |

| Cystic fibrosis | 4 033 | 706 | 5.7 | 5.1 (4.9 to 5.4) |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | 3 797 841 | 566 643 | 6.7 | 6.1 (6.1 to 6.2) |

| Lung cancer | 23 824 | 1 846 | 12.9 | 7.9 (7.5 to 8.2) |

| Mesothelioma | 941 | 69 | 13.6 | 4.1 (3.6 to 4.6) |

| Occupational lung disease | 27 441 | 3 345 | 8.2 | 6.7 (6.5 to 6.9) |

| Pneumonia | 311 762 | 44 069 | 7.1 | 6.1 (6.1 to 6.1) |

| Tuberculosis | 99 045 | 13 762 | 7.2 | 5.2 (5.1 to 5.2) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 6 099 503 | 1 162 796 | 5.3 | 5.5 (5.5 to 5.5) |

| All patients | 12 749 498 | 2 958 366 | 4.3 | 4.3 (4.3 to 4.3) |

Smoking trends

Between 2001 and 2005, the overall prevalence of smoking among patients with COPD decreased from 39.2% (95% CI = 37.1 to 48.3) to 36.7% (95% CI = 33.6 to 42.4), a 2.5% reduction (P<0.001). In 2005, the highest prevalence of smoking was found among women with COPD aged 45–50 years of age who were in the most deprived quintile (72.3% [95% CI = 62.7 to 81.9]). During the study period, among the most deprived group of patients with COPD, there was a much smaller decrease in the proportion smoking when compared with the most affluent group (Table 6).

Table 6.

Proportion of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) recorded as smokers.

| Year and Townsend quintile | Total COPD patientsa | Smokers | Crude % | Age–sex-standardised % (95% CI) | Change in standardised rate (from 2001) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | |||||

| 1 (most affluent) | 5 233 | 1 427 | 27.3 | 29.9 (23.7 to 43.3) | N/A |

| 2 | 5 527 | 1 648 | 29.8 | 31.6 (24.5 to 45.3) | N/A |

| 3 | 6 476 | 2 190 | 33.8 | 35.9 (30.6 to 48.2) | N/A |

| 4 | 7 724 | 2 986 | 38.7 | 38.0 (33.9 to 48.7) | N/A |

| 5 (most deprived) | 10 680 | 4 971 | 46.5 | 46.6 (43.1 to 50.6) | N/A |

| 2005 | |||||

| 1 (most affluent) | 7 763 | 1 770 | 22.8 | 23.4 (19.6 to 33.6) | –6.5 |

| 2 | 7 993 | 1 986 | 24.9 | 27.5 (24.0 to 38.1) | –4.1 |

| 3 | 9 550 | 2 760 | 28.9 | 31.8 (28.3 to 38.2) | –4.1 |

| 4 | 10 680 | 3 743 | 35.1 | 37.2 (32.9 to 44.1) | –0.8 |

| 5 (most deprived) | 14 078 | 5 969 | 42.4 | 45.3 (39.2 to 57.1) | –1.3 |

With smoking status recorded. N/A = not applicable.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

This study, using routinely collected electronic data from one of the world’s largest national primary care datasets, has confirmed that physician-diagnosed COPD is common and results in considerable use of healthcare services in general practice. The study data reveal very considerable regional and socioeconomic inequalities in the diagnosed prevalence of COPD, which have become more pronounced over the study period. Encouragingly, there was a significant reduction in smoking prevalence among these patients, although this was more marked among affluent patients than among those who were more socioeconomically deprived.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The main strengths of this study include the interrogation of patient-level computerised data from an extremely large nationally representative dataset, and the fact that all contributing practices used the same computing systems for electronically recording clinical data. The study design employed ensured that there was no risk of selection bias due to non-responders or recall bias.

There are a number of limitations related to the use of large routinely collected data from primary care, including the dependence on clinician-recorded diagnosis of COPD (especially as the reliability of diagnosis and recording could not be checked; for example, spirometry data were not available to confirm or refute clinical diagnoses) and possible improvements in recording over the study time period, which may not reflect the true incidence or prevalence of disease in the community.

There may also be an underestimate in relation to the actual population prevalence of COPD, especially in individuals with mild disease who may not have consulted a primary care physician. As there is a considerable delay between changes in the causative factors of COPD and its presentation, the relatively short time window over which trends were studied is another limitation, and therefore it is possible that changes in incidence and prevalence between one year and the next are more likely to reflect changes in health service use and changes in physician recognition of the disease (rather than changes in true prevalence). In particular, the introduction of the new General Medical Services contract to UK primary care in April 2004,14 which introduced incentives to create and maintain a registry of patients with COPD, may be a cause of the increase in case ascertainment found in the penultimate year of the study.

It is also possible that the introduction of the new contract caused some diagnostic drift from patients labelled as having asthma to COPD, and that the contract requirement for a more systematic reliable diagnosis of COPD, confirmed by spirometry and reversibility testing for new patients (introduced in 2005), and all patients (introduced in 2006), may have further impacted the incidence and prevalence of physician-diagnosed COPD after this study period. However, despite the possibility of confusion with other airways disorders,15 a good correspondence has been found between clinician and electronic patient diagnoses of COPD and differentiation between asthma.16

Comparison with existing literature

The incidence rate of 2.0 per 1000 patient-years was similar to that found among young European adults (2.8 per 1000 patient-years),17 but higher than the annual average incidence found among adults in Bergen, Norway (0.7% annual incidence).18 It is likely that this lower incidence is due to the use of different disease criteria rather than differences in environmental exposure. Lifetime prevalence in the present study (1.7%) was less than that found using a questionnaire survey of patients (aged ≥30 years) from two primary care practices in Manchester, England (4.1%),19 and less than the prevalence found using Dutch general practice data (5.5%),20 and also estimates from the Health Survey for England 2001 (women 2.4%; men 3.9%),21 but similar to prevalence estimates reported by the Quality and Outcomes Framework (1.5%).22 Prevalence rates at the beginning of the study period in 2001 (female: 1.3%; male 1.5%) were also very similar to those found in 1997 using the UK General Practice Research Database (female 1.4%; male 1.6%).4

Higher rates of COPD diagnosed in primary care in northern England and deprived communities found in the present study have also been previously reported.23 Mean consultation rates (7.9 per year) were higher than those from a survey conducted in 2002 of 500 patients throughout the UK with COPD (6.6 visits per year), although this was a telephone survey that relied on patient recollection and may have been affected by recall bias.24

Implications for future research and clinical practice

Given the peak in the incidence rate of COPD and the substantial decreases in prevalence of smoking in the overall population,5 it is likely that we are approaching the peak of COPD incidence and prevalence in England. Rather than any increases in causative factors that may have occurred in previous decades, increases in the prevalence of physician-diagnosed COPD recorded by general practice during the study period, and the increase of COPD incidence in 2004, are likely to represent not only the continuing impact of increasing survival among patients,16 but also the increased clinician awareness of COPD. This is largely due to the imminent introduction of a new incentive-based quality-improvement contract in April 2004,14 which led to improvements being made in identifying and recording individuals with the disease. The higher rate of consultations found here is a reflection of the high use of primary healthcare services by patients with COPD.

Given these issues, healthcare planners need to consider that patients with COPD are greater users of healthcare services, with more individuals being diagnosed by physicians with COPD, and that continuing efforts are required to diagnose this disease early so that effective management can be provided.25 It is also apparent that additional burden is placed on services in the north east of England and the most deprived communities where, for those with the disease, there have been only very modest declines in the rates of smoking. This is a cause for concern and poses a challenge for health services, as it is recognised that COPD may still progress in individuals even if they quit smoking. With the imminent publication of the Clinical Strategy for COPD,26 it is clear that there is a need for the continued provision of resources for promotion of smoking cessation, monitoring, pulmonary rehabilitation, and management of patients with COPD, particularly for those in the north east of the country and in the most deprived communities in England.

Acknowledgments

We would like to record our thanks to the contributing EMIS practices and patients, and to EMIS for providing technical expertise in creating and maintaining QRESEARCH. We thank QRESEARCH staff for their contribution to data extraction, analysis, and presentation. These findings have been reported in Primary care epidemiology of allergic disorders: analysis using QRESEARCH database 2001–2006, which is published by the NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre.

Funding body

Colin R Simpson is supported by a Health Services and Health of the Public postdoctoral fellowship from the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government (PDF/08/02).

Ethical approval

All data analyses were conducted using de-identified data and were subject to the QRESEARCH research governance processes.

Competing interests

Julia Hippisley-Cox is Director of QRESEARCH (a not-for-profit organisation owned by the University of Nottingham and EMIS, commercial supplier of computer systems for 60% of GP practices in the UK). Colin R Simpson and Aziz Sheikh have no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp–discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. World Health Report: life in the 21st century: a vision for all. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niu S, Yang G, Chen Z, et al. Emerging tobacco hazards in china: 2 early mortality results from a prospective study. BMJ. 1998;317(7170):1423–1424. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7170.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calverley PMA. Caring for the burden of COPD. Thorax. 2006;61(10):831–832. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.060855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soriano JB, Maier WC, Egger P, et al. Recent trends in physician diagnosed COPD in women and men in the UK. Thorax. 2000;55(9):789–794. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.9.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Her Majesty’s Treasury. 2004 spending review public service agreements 2005–8. London: Her Majesty's Treasury; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simpson CR, Hippisley-Cox J, Sheikh A. Trends in the epidemiology of smoking in the United Kingdom. Br J Gen Pract. 2010 doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X483544. 10.3399/bjgp10X483544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Chief Medical Officer. On the state of the public health: annual report of the Chief Medical Officer. London: The Department of Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hippisley-Cox J, Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Pringle M. Comparison of key practice characteristics between general practices in England and Wales and general practices in the QRESEARCH data. http://www.qresearch.org/Public_Documents/Characteristics%20of%20QRESEARCH%20practices%20_database%20version%208_%20v1.0.pdf (accessed 1 Jun 2010)

- 9.Sheikh A, Hippisley-Cox J, Newton J, Fenty J. Trends in national incidence, lifetime prevalence and adrenaline prescribing for anaphylaxis in England. J R Soc Med. 2008;101(3):139–143. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2008.070306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghouri N, Hippisley-Cox J, Newton J, Sheikh A. Trends in the epidemiology and prescribing of medication for allergic rhinitis in England. J R Soc Med. 2008;101(9):466–472. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2008.080096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simpson CR, Newton J, Hippisley-Cox J, Sheikh A. Incidence and prevalence of multiple allergic disorders recorded in a national primary care database. J R Soc Med. 2008;101(11):558–563. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2008.080196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simpson CR, Newton J, Hippisley-Cox J, Sheikh A. Trends in the epidemiology and prescribing of medication for eczema in England. J R Soc Med. 2009;102(3):108–117. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2009.080211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Office for National Statistics. The 2001 census. http://www.ons.gov.uk/census/index.html (accessed 18 Jan 2010)

- 14.The NHS Confederation. Investing in general practice: the new General Medical Services contract. London: British Medical Association; http://www.bma.org.uk/employmentandcontracts/independent_contractors/general_medical_services_contract/investinggp.jsp (accessed 18 Jan 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolfenden H, Bailey L, Murphy K, Partridge MR. Use of an open access spirometry service by general practitioners. Prim Care Respir J. 2006;15(4):252–255. doi: 10.1016/j.pcrj.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soriano JB, Vestbo J, Pride NB, et al. Survival in COPD patients after regular use of fluticasone propionate and salmeterol in general practice. Eur Respir J. 2002;20(4):819–825. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00301302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Marco R, Accordini S, Cerveri I, et al. Incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a cohort of young adults according to the presence of chronic cough and phlegm. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(1):32–39. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-381OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johannessen A, Omenaas E, Bakke P, Gribbin J. Incidence of GOLD-defined chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a general adult population. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9(80):926–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frank TL, Hazell ML, Linehan MF, et al. The estimated prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a general practice population. Prim Care Respir J. 2007;16(3):169–173. doi: 10.3132/pcrj.2007.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bischoff EWMA, Schermer TRJ, Bor H, et al. Trends in the COPD prevalence and exacerbation rates in Dutch primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59:927–933. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X473079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nacul LC, Soljak M, Meade T. Model for estimating the population prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: cross sectional data from the Health Survey for England. Popul Health Metr. 2007;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Prescribing Support Unit. Quality and Outcome Framework disease prevalence for April 2007 to March 2008, England. Leeds: The Health and Social Care Information Centre; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith CJP, Gribben J, Challen KB, Hubbard RB. The impact of the 2004 NICE guideline and 2003 General Medical Services contract on COPD in primary care in the UK. Q J Med. 2008;101(2):145–153. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Britton M. The burden of COPD in the UK. Results from the confronting COPD survey. Resp Med. 2003;97:S71–S79. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(03)80027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones R. Can early diagnosis and effective management combat the irresistible rise of COPD. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(530):652–654. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The British Lung Foundation. National clinical strategy for COPD. London: The British Lung Foundation; http://www.lunguk.org/media-and-campaigning/campaigns/what_is_the_national_strategy_for_copd.htm (accessed 18 Jan 2010) [Google Scholar]