Abstract

Objective

Research has shown an association between depression and functional limitations in older adults. Our aim was to explore the latent traits of trajectories of limitations in mobility and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) tasks in a sample of older adults diagnosed with major depression.

Methods

Participants were 248 patients enrolled in a naturalistic depression treatment study. Mobility/IADL tasks included walking ¼ mile, going up/down stairs, getting around the neighborhood, shopping, handling money, taking care of children, cleaning house, preparing meals, and doing yardwork/gardening. Latent class trajectory analysis was used to identify classes of mobility/IADL function over a 4-year period. Class membership was then used to predict functional status over time.

Results

Using time as the only predictor, three latent class trajectories were identified: 1) Patients with few mobility/IADL limitations (42%), 2) Patients with considerable mobility/IADL limitations (37%), and 3) Patients with basically no limitations (21%). The classes differed primarily in their initial functional status, with some immediate improvement followed by no further change for patients in classes 1 and 2, and a stable course for patients in class 3. In a repeated measures mixed model controlling for potential confounders, class was a significant predictor of functional status. The effect of baseline depression score, cognitive status, self-perceived health, and sex on mobility/IADL score differed by class.

Conclusions

These findings show systematic variability in functional status over time among older patients with major depression, indicating that a single trajectory may not reflect the pattern for all patients.

Keywords: depression, physical function, latent class analysis

Introduction

The cross-sectional relationship between depressive symptoms and limitations in physical functioning in older adults has been well documented in both community and clinical samples (Bruce, 2001; Lenze et al., 2001).

In longitudinal community samples, depressive symptoms have been shown to predict functional decline, as measured by both self-reported and objective measures of physical performance (Penninx et al., 1998; 1999; Wang et al., 2002), and to predict onset of limitations in basic activities of daily living (ADLs) in high functioning older adults initially free of disability (Bruce et al., 1994). The likelihood of becoming disabled increases with each additional depressive symptom (Beckett et al., 1996), and depressive symptoms may accelerate the disablement process in older adults with early signs of disability (van Gool et al., 2005). Individuals with chronic depressive symptoms have greater decline in function compared to those who remained nondepressed (Lenze et al., 2005; Penninx et al., 2000). Similar findings have been reported among older primary care patients (Callahan et al., 1998). Some studies, however, have not found a longitudinal relationship (Everson-Rose et al., 2005), suggesting that there is not a single trajectory of function associated with depressive symptoms.

The relationship between depression and function in older patients with major depression is complex. Using cross-sectional data, Steffens et al. (1999) found that less reported depressed mood was associated with deficits in self-maintenance activities, while greater severity of depression was associated with impairments in instrumental ADLs (IADLs). Alexopoulos et al. (1996) reported that impairment in IADLs was associated with advanced age, severity of depression and medical burden in a sample of older adults with major depression. The relationship of depression severity to IADL function was independent of medical burden.

In a sample of 2572 older inpatients with a DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) depressive disorder followed for three months, improvement in depressive symptomatology was significantly related to improvement in IADLs. The relationship was strongest among those who initially presented with some IADL disability. The authors concluded treating the depression could lead to improvement in function, or at a minimum prevent further deterioration (Oslin et al., 2000). Similarly, in the IMPACT study, patients with either major depression or dysthymia whose depression improved were more likely to experience improvement in physical functioning one year later (Callahan et al., 2005).

The purpose of our analyses was to extend earlier findings by focusing on older patients with major depression, and by following the patients beyond one year to identify trajectories of mobility/IADL function. We chose to focus on major depression to examine functional outcomes in a more severely depressed sample, since research has suggested that the relationship between depression and disability may be stronger in patients with minor depression compared to major depression (Beekman et al., 1997). We chose to extend the follow-up period because previous work in older adults has shown functional decline can be reversible and mobility status can be dynamic (Beckett et al., 1996; Branch et al., 1984; Gill et al., 2006; Hardy et al., 2005), and the course of depression often exceeds one year. We chose to focus on IADL limitations because they have a mental as well as physical component that could be linked to depression (Kiosses and Alexopoulos, 2005; Lenze et al., 2001), and on mobility limitations because these often mark the beginning of decline (Katz, 1983). We were also interested in examining trajectories of function in which variables previously reported to be associated with functional limitations would be controlled. These include demographic variables (older age, female sex, and lower education), clinical variables (more severe depression and later age of onset of depression), health variables (medical burden, poorer self-rated health and deficits in cognitive functioning), and social variables such as lower subjective social support (Alexopoulos et al., 1996; Beckett et al., 1996; Dodge et al., 2006; Kempen et al., 2006; Kivela and Pahkala, 2001; Steffens, Hays, and Krishnan, 1999). We were particularly interested in undertaking analyses which would be qualitatively different to those in the literature to address functional outcomes of late life depression. Our intent was to provide findings that would add to the literature by 1) focusing on patients with major depression undergoing naturalistic treatment, 2) extending the length of follow-up beyond what had been previously done, and 3) by testing whether one pattern of functional recovery best fit this group of patients or whether there were different trajectories of functional change within a sample of patients with one diagnosis. These results could be helpful in formulating hypotheses for future studies examining longitudinal outcomes of major depression in older adults and in providing clinical insights into particular variables that may affect functional outcomes.

Our overall aim was therefore to explore the latent traits of trajectories of mobility/IADL limitations in a sample of older adults diagnosed with major depression and followed for up to four years. We hypothesized there would be variability in functional status over time (i.e., multiple trajectories), and that these trajectories would be differentially associated with demographic, clinical, health and social variables previously found to predict functional status in older adults.

Methods

Sample Design

The sample comprised inpatients and outpatients age 60 or older who met DSM-IV criteria for major depression, recruited through both psychiatry and primary care clinics at Duke University Medical Center. The patients were participants in the NIMH Mental Health Clinical Research Center (MHCRC) for the Study of Depression in Late Life, and included both new (incident) and recurrent (prevalent) cases. Exclusion criteria were any comorbid major psychiatric illness such as schizophrenia, active alcohol or drug abuse or dependence, any primary neurologic illness, and metal in the body which precluded MRI imaging of the brain. The focus of the MHCRC was to examine cognitive outcomes of depression, and patients with severe cognitive limitations were not recruited into the study. Patients with lower cognitive scores initially which later improved with depression treatment were eligible for participation. This study has been described previously (Hybels, Blazer, and Steffens, 2005; Steffens, McQuoid, and Krishnan, 2003).

The MHCRC is an ongoing longitudinal naturalistic treatment study. Patients are followed clinically and treated according to the Duke Somatic Treatment Algorithm for Geriatric Depression (STAGED) guidelines (Steffens, McQuoid, and Krishnan, 2002). Pharmacologic treatment included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), lithium, and other antidepressants. Some patients had psychotherapy and/or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) during the course of the study.

A total of 393 patients had been enrolled at the time of this analysis. Sixty five patients were dropped because they had only a baseline measure of functional status. Those with one measure of function were more likely to be female, not married, have fewer years of education, and lower subjective social support scores compared to those with two or more measures. An additional eighty patients were dropped because of missing data on one or more of the key variables, yielding an analysis sample of 248 patients. All patients provided written consent to participate at the time of enrollment. The research protocol is reviewed and approved by the Duke Institutional Review Board (IRB) annually.

Measures

The outcome variable was mobility/IADL limitations, assessed annually through self-report. We used measures from the first four years following study enrollment, and therefore, had up to five measures per patient. Patients were asked how much difficulty they had: walking ¼ mile, walking up and down a flight of stairs without resting, getting around the neighborhood, shopping for groceries and other household articles, keeping track of money/bills, taking care of and watching children, cleaning house, preparing meals, and doing yardwork or gardening. Responses were coded as able to do (code=1), able to do but with difficulty (code=2), and unable to do (code=3). Possible scores ranged from 9–27 (recoded to 0–18). Higher numbers indicated more limitation in function. Before combining the items into one scale, we conducted a factor analysis of the nine activities at their baseline level using data from participants with at least three years of functional data, and found that all the items loaded onto one factor.

Explanatory variables previously found to be associated with functional status in older adults were used to identify characteristics associated with each trajectory or class and as potential confounders in the analysis. Variables were included in the models at their baseline value. Demographic variables included age, sex, race (White vs Non-White), marital status (married vs. not married) and years of education. Clinical variables included depression score from the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery and Asberg, 1979) with a possible range of values of 0–60, age of onset of depression in years, and number of lifetime spells of depression (3+ vs. <3). Health variables included self-perceived health (excellent/good vs. fair/poor) and cognitive status, measured using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein, Folstein, and McHugh, 1975), with lower scores indicating poorer cognitive function. Social variables included subjective social support, measured by asking ten questions relating to feeling useful and listened to and satisfaction with social relationships. The responses were summed, and the total was used as a continuous variable (possible range 10–29), with greater values indicating higher levels of perceived support. We also included a measure of perceived stress, a continuous variable with 1 indicating no stress and 10 severe stress.

Statistical Analyses

We ran a repeated measures mixed model using SAS PROC MIXED (SAS Institute, 2004) to predict the mean trajectory of mobility/IADL function over the four-year period. We included time as the only predictor, followed by a model including potential confounders. We tested whether the effect from baseline status was statistically different from the post-baseline effects within the mixed model. The baseline effect was significant compared to the other intervals (t[241]=3.47, p=0.0006) while the post baseline effects did not differ across years. We therefore included a variable (Baseline Y/N) to control for the influence on the trajectory of the first interval. Although the number of mobility/IADL limitations was somewhat skewed, we plotted the residuals from the mixed model and they appeared to follow a normal distribution. To best model the correlated errors, we tested several covariance structures. Using Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), an unstructured covariance structure provided the best fit to the data.

To identify latent traits of the trajectories of change, we ran latent class trajectory analysis (LCTA), an extension of a repeated measures mixed model, using Latent Gold software (Vermunt and Magidson, 2005a; 2005b). Mixed models with a mean trajectory assume a central value for all subjects and that the surrounding variance is random. LCTA allowed us to address our research objective exploring whether a single mean trajectory adequately reflected the group, or whether multiple trajectories would better describe the course of functional status among these patients. In LCTA, patients are assigned to classes based on posterior membership probability (Vermunt and Magidson, 2005a; 2005b). We then used mixed models to determine the average trajectory of function over time for each class, controlling for variables known to be associated with functional status.

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample at baseline. The patients were predominantly White, female, and well-educated. The majority of patients had few or no mobility/IADL limitations at baseline (mean=3.7, median=2.0), but 21% of the sample had a score of 7 or higher.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample at baseline (n=248)

| Demographic Characteristics | |

| Mean age in years (std) | 68.8 (7.0) |

| Number White (%) | 218 (87.9%) |

| Number Female (%) | 154 (62.1%) |

| Mean years of education (std) | 13.9 (2.9) |

| Number not married (%) | 99 (39.9%) |

| Clinical Variables | |

| Mean MADRS score (std) | 23.7 (9.8) |

| Mean age of onset (std) | 43.3 (20.4) |

| Number with 3 or more lifetime spells of depression (%) | 159 (64.1%) |

| Health Variables | |

| Number self-rated health fair or poor (%) | 119 (48.0%) |

| Mean MMSE score (std) | 28.1 (2.4) |

| Social Variables | |

| Mean score for subjective social support (std) | 23.3 (3.9) |

| Mean score for perceived stress (std) | 6.5 (2.1) |

| Mean mobility/IADL score at baseline (std) | 3.7 (4.7) |

Mean trajectory model

A mean trajectory model using PROC MIXED with time and baseline as the only predictors indicated the effect of the first year was significant, but the effect of time was not, suggesting that after controlling for the immediate change after enrollment, functional status did not significantly change over time. These results remained essentially unchanged when potential confounders were added to the model. Mobility/IADL limitations were predicted by older age, fair or poor self-rated health, female sex, higher baseline MADRS score, less education, lower MMSE score, and lower levels of perceived social support. We tested two higher order polynomials. A likelihood ratio test comparing a model with cubic, squared, and linear terms for time to a model with only a linear term was not significant, suggesting that the effect of time controlling for the first interval was linear.

Latent class trajectory analysis

Using Latent Gold software, we determined the optimal number of latent classes by comparing models with 1–5 classes using time and baseline as the only predictors. Using the BIC statistic and the need for sufficient class size for model stability, a three-class model provided the best fit to the data. Table 2 shows the results of the LCTA. Classes are numbered by size.

Table 2.

Results of the latent class trajectory analysis with time and baseline interval as predictors

| Class 1 (n=104) | s.e. | z | Class 2 (n=91) | s.e. | z | Class 3 (n=53) | s.e. | z | Wald | p | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.2769 | 0.11 | 11.74 | 6.8069 | 0.47 | 14.57 | 0.0000 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 330.65 | <.0001 | 3.0643 |

| Predictors | ||||||||||||

| Time | −0.0048 | 0.07 | −0.07 | 0.1355 | 0.33 | 0.41 | 0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.92 | 0.0485 |

| Baseline | 0.4484 | 0.11 | 4.19 | 1.1750 | 0.45 | 2.60 | 0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 23.69 | <.0001 | 0.6234 |

At baseline, patients in class 1 (42%) had low scores on the mobility/IADL measure, patients in class 2 (37%) had higher scores, and patients in class 3 (21%) had few to no limitations. The Wald tests test if the intercepts and slopes were significantly different across the latent classes. The Wald test for the intercepts was significant. The effect of time, controlling for the baseline interval, did not vary across classes and was not significant. The overall baseline effect was significant, and differed by class. Patients in classes 1 and 2 had a decrease (improvement) in function score the first year, while patients in class 3 showed no significant change. The mean scores in the last column represent a weighted average of the class specific intercepts and slopes and what we would observe in a mean trajectory model.

Within the context of LCTA, we explored the relationship between variables previously shown to affect function and the trajectories (analysis not shown). We first added these variables in a manner that allowed them to affect class membership. No variables were significantly associated with class 1. In contrast, older age, being female, fewer years of education, higher baseline MADRS score, fair/poor self-perceived health, and lower perceived social support were associated with membership in class 2. Younger age, male sex, excellent/good self-rated health, and higher levels of subjective social support were associated with class 3. We then added these variables to the model allowing them to affect the slope instead of class membership for each trajectory. The effect on mobility/IADL function of age, being female, and years of education varied by class, while the effect of race and marital status did not. The effect of both health variables (self-perceived health and MMSE score) varied by class, while the effect of the clinical and social variables did not differ by class.

Functional outcomes by class using mixed models

LCTA utilizes maximum likelihood to estimate the course of functional status, and the trajectories are based on marginal means. We chose instead to use the estimated classes to model change by class using a mixed model approach. These results are shown in Table 3. The effect of time was not significant, while the effect of the first interval varied by class, as did the effect on functional status of MMSE score, MADRS score, self-perceived health, and being female. The classes did not appear to change at a differential rate, but differed primarily in the mobility/IADL score at the beginning of the study.

Table 3.

Results of the final mixed model showing the effect of class predicting the course of mobility/IADL function over four years controlling for potential confounders (882 observations from 248 patients)

| Class | Parameter Estimate | Standard Error | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −3.598 | 5.623 | ||

| Time | 0.019 | 0.204 | F(1,153)=2.26, p=0.1347 | |

| Baseline interval | 0.018 | 0.572 | F(1,245)=16.22, p<.0001 | |

| Class | 1 | 1.291 | 6.211 | F(2,215)=8.48, p=0.0003 |

| 2 | 15.472 | 5.650 | ||

| 3 | 0 | |||

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||

| Age in years | 0.048 | 0.020 | F(1,199)=5.82, p=0.0168 | |

| White race | 0.151 | 0.402 | F(1,200)=0.14, p=0.7069 | |

| Female | −0.056 | 0.520 | F(1,193)=5.20, p=0.0237 | |

| Years of education | −0.114 | 0.048 | F(1,204)=5.64, p=0.0185 | |

| Not married | −0.092 | 0.271 | F(1,183)=0.12, p=0.7347 | |

| Clinical Variables | ||||

| Baseline MADRS score | −0.010 | 0.028 | F(1,168)=6.14, p=0.0142 | |

| Age of onset | −0.001 | 0.008 | F(1,172)=0.00, p=0.9528 | |

| 3 + lifetime depression spells | 0.265 | 0.310 | F(1,180)=0.73, p=0.3945 | |

| Health Variables | ||||

| Fair/poor self-perceived health | 0.099 | 0.629 | F(1,184)=10.25, p=0.0016 | |

| MMSE Score | 0.097 | 0.180 | F(1,218)=2.16, p=0.1428 | |

| Social Variables | ||||

| Subjective social support | −0.037 | 0.035 | F(1,181)=1.14, p=0.2870 | |

| Perceived stress | 0.023 | 0.061 | F(1,196)=0.14, p=0.7101 | |

| Time * class | 1 | 0.026 | 0.249 | F(2,153)=1.47, p=0.2323 |

| 2 | 0.365 | 0.263 | ||

| 3 | 0 | |||

| MMSE Score * class | 1 | −0.039 | 0.210 | F(2,209)=11.88, p<.0001 |

| 2 | −0.600 | 0.191 | ||

| 3 | 0 | |||

| Baseline MADRS * class | 1 | 0.017 | 0.036 | F(2,164)=8.39, p=0.0003 |

| 2 | 0.116 | 0.034 | ||

| 3 | 0 | |||

| Fair/poor self-rated health * class | 1 | 0.152 | 0.732 | F(2,184)=7.71, p=0.0006 |

| 2 | 2.302 | 0.778 | ||

| 3 | 0 | |||

| Female * class | 1 | 0.168 | 0.638 | F92,194)=5.00, p=0.0077 |

| 2 | 1.914 | 0.710 | ||

| 3 | 0 | |||

| Baseline interval * class | 1 | 0.784 | 0.705 | F(2,246)=7.10, p=0.0010 |

| 2 | 2.513 | 0.723 | ||

| 3 | 0 | |||

We tested a series of models assessing interactions with class and time. None of the possible 3-way interactions (each potential confounder * time* class) or 2-way interactions with time (each potential confounder*time) was significant, and these terms were removed. The addition of the group of 2-way interactions with class (each potential confounder*class) was significant (χ2 [8]=92.1, p<.0001), indicating some of these variables had differential impact on the level of function depending on class membership. We removed two nonsignificant interaction terms one at a time (years of education and age), and left the remaining product terms in the model.

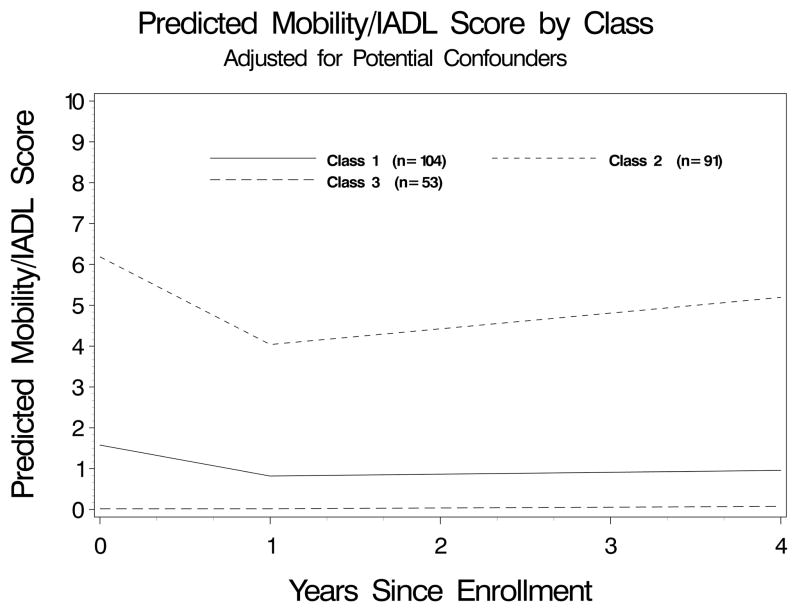

Figure 1 shows the predicted trajectories from the mixed model for the three classes controlling for the effect of the potential confounders. The reference group is the patients assigned to class 3, who remain basically free of limitations. Patients in class 1 appear to have more limitations than those in class 3, but also appear to show little absolute or relative change over time after the first year. The patients in class 2 have more limitations at baseline than those in either class 1 or 3, appear to show a decrease in limitations the first year, and then appear to maintain a poor trajectory of function. The influence of the potential confounders in the data can be observed by comparing the slopes to those in the uncontrolled model presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Predicted Mobility/IADL Score by Class Adjusted for Potential Confounders (MMSE score, MADRS score, self-rated health, and female sex set to the mean)

As a final step, to further understand the interpretation of the first interval, we examined change in MADRS score and change in function the first year. The change scores were significantly correlated (Pearson correlation coefficient=0.25, p<.0001). MADRS scores declined on average 14.3 points the first year, while mobility/IADL scores declined 1.1 units.

Discussion

We report new findings from this study of older adults diagnosed with major depression and followed for up to four years. Using state-of-the-art statistical techniques to address functional outcomes of late life depression, we found systematic differences in functional status over time, suggesting that a single trajectory may not reflect the pattern for all patients. Some patients remained free of mobility/IADL limitations over time. Among patients initially presenting with limitations, we did not see gradual improvement over the course of the study but rather improvement the first year, followed by stabilization. Patients in the group with the most limitations were more likely to be female, have higher initial MADRS score, lower MMSE scores, and poorer self-rated health. To the best of our knowledge this study is the first to explore the multi-year course of functional status in older adults receiving usual care for major depression. These findings suggest that functional decline secondary to major depression may be a transient phenomenon in terms of its immediate impact. The eventual level of functional status may represent an underlying level of function that may not be associated with the depression.

Our findings of initial improvement in this naturalistic treatment study are consistent with those reported from the IMPACT study (Callahan et al., 2005). By extending the follow-up period and using a different analytic approach, we found a multi-trajectory model fit the data better than a single trajectory model. There appeared to be three classes of patients based on their mobility/IADL scores over the four-year period. The classes of patients differed primarily in initial functional status and change in limitations over the first year. We did not observe differential changes after the first year. MMSE score, MADRS score, self-perceived health and sex were associated with functional status. We conclude the data support our hypotheses that a single trajectory may not reflect the pattern for this group of patients over a four-year period and that the trajectories would be differentially associated with some variables thought to predict functional status.

In our three-class model, the effect of MMSE score was associated with function in Classes 2 and 3 but not Class 1. This differential effect by class is consistent with results from a community sample of nondemented older adults showing that trajectories of IADL disabilities varied by cognitive status (Dodge et al., 2006). Our study was limited to patients with good cognitive functioning, so any effects of lower cognitive status may be due to lower scores which were more transient and later improved. We did not find subjective social support predicted mobility/IADL limitations. Research has suggested that other dimensions of social support, particularly instrumental social support, may be more important components of the depression/disability association (Hays et al., 2001; Travis et al., 2004).

Our study has several strengths. The sample has been carefully characterized and followed using standardized procedures. The analytic procedures allow for individual measures to be correlated over time, and allow patients to be included in the analysis even if some data points are missing. By allowing more than one mean trajectory, these analyses can address whether there is heterogeneity in the course of functional status among older adults with major depression.

Our research is not without limitations. Our patients are mostly White, well-educated, and physically able to return for follow-up, so our results may not be generalizable to all depressed older adults. This may partially explain why we did not observe a general decline in function over the 4-year period in our sample. We assessed function through self-report, and depression may confound reporting, although perhaps confounding more for role functioning than for functional limitations (Sinclair et al., 2001). Our latent classes were determined by time (and baseline) alone. Our models included only time-invariant predictors measured at baseline and therefore did not allow the effect of the predictor variables to vary over time (Singer and Willett, 2003). We were interested in exploring the effect of the predictors at their baseline level on trajectories of functional change and therefore did not focus on time varying covariates such as changes in MADRS score. We do not know which of these patients met criteria for current major depression at follow-up. Changes in depression severity, in particular, may affect trajectories of function, as depression and function share a reciprocal relationship in older adults (Bruce, 2001; Gurland, Wilder, and Berkman, 1988). Other variables in our model including self-perceived health, MMSE score, social support and perceived stress may also vary over time. Concurrent changes over time will be the subject of future work. Our waves were one year apart, and may not capture brief episodes of functional change (Hardy et al., 2005). We also experienced some patient attrition, and the attrition was not random. Over the 4-year period, 79 (32%) of the patients were lost to follow-up. Thirty-eight percent of the patients in Class 2 with the poorest trajectory had incomplete follow-up, compared to 18% in Class 1 and 15% in Class 3. Because most of the patients were initially healthy, we did not control for medical illness and instead focused on self-rated health, which has been shown to be a strong predictor of health outcomes (Idler and Benyamini, 1997). Although we cannot state these patients were in treatment over the entire follow-up period, they were under the care of a geriatric psychiatrist working within an academic medical center. As indicated earlier, patients received pharmacologic therapies, ECT, and psychotherapy as needed. We do not suspect functional limitations are associated with any particular depression treatment.

Conclusion

These findings provide additional data showing functional limitations associated with late life depression have the potential to improve. Our scores reflect both the presence of limitations and degree of functional difficulty. Because function and depression can be reciprocal, interventions to help reduce difficulty with functioning could be clinically important for depression. We conclude there is variability in trajectories of mobility/IADL in depressed older adults in usual care. In general, both major depression and the functional limitations secondary to depression may be self-limiting. Female patients or those with more severe depression at the index episode, initial signs of cognitive impairment or poorer health may be at particular risk for a poor trajectory of functional outcome. Future research will explore conjoint trajectories of depression and function to examine the correlation of depression and function over time.

Key Points.

Depressive symptoms have been shown to predict functional decline in older adults.

Treatment of depression has been shown to improve functional status over a one-year period.

There is considerable variability in trajectories of mobility/IADL function over a multi-year period in depressed older adults being followed through usual care.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIMH grants K01 MH066380, K24 MH70027, R01 MH54846, P50 MH60451, and the Claude G. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center 1P30 AG028716.

Footnotes

The authors report no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Celia F. Hybels, Email: cfh@geri.duke.edu, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, Box 3003, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, Phone: (919) 660-7546, FAX: (919) 668-0453.

Carl F. Pieper, Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.

Dan G. Blazer, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.

Gerda G. Fillenbaum, Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, Duke University Medical Center, and Geriatrics, Education, and Clinical Center, Veterans Administration Medical Center, Durham, NC.

David C. Steffens, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.

References

- Alexopoulos GS, Vrontou C, Kakuma T, Meyers BS, Young RC, Klausner E, Clarkin J. Disability in geriatric depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:877–885. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.7.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett LA, Brock DB, Lemke JH, Mendes de Leon CF, Guralnik JM, Fillenbaum GG, Branch LG, Wetle TT, Evans DA. Analysis of change in self-reported physical function among older persons in four population studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:766–778. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, Braam AW, Smit JH, van Tilberg W. Consequences of major and minor depression in later life:A study of disability, well-being, and service utilization. Psychol Med. 1997;27:1397–1409. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branch LG, Katz S, Kniepmann K, Papsidero JA. A prospective study of functional status among community elders. Am J Public Health. 1984;74:266–268. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML. Depression and disability in late life: Directions for future research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9:102–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, Seeman TE, Merrill SS, Blazer DG. The impact of depressive symptomatology on physical disability: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:1796–1799. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.11.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan CM, Kroenke K, Counsell SR, Hendrie HC, Perkins AJ, Katon W, Noel PH, Harpole L, Hunkeler EM, Unutzer J for the IMPACT investigators. Treatment of depression improves physical functioning in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:367–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan CM, Wolinsky FD, Stump TE, Nienaber NA, Hui SL, Tierney WM. Mortality, symptoms, and functional impairment in late-life depression. Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:746–752. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge HH, Du Y, Saxton JA, Ganguli M. Cognitive domains and trajectories of functional independence in nondemented elderly persons. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2006;61A:1330–1337. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.12.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson-Rose SA, Skarupski KA, Bienias JL, Wilson RS, Evans DA, Mendes de Leon CF. Do depressive symptoms predict declines in physical performance in an elderly, biracial population? Psychosom Med. 2005;67:609–615. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000170334.77508.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh P. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for clinicians. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill TM, Allore HG, Hardy SE, Guo Z. The dynamic nature of mobility disability in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:248–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurland BJ, Wilder DE, Berkman C. Depression and disability in the elderly: Reciprocal relations and changes with age. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1988;3:163–179. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy SE, Dubin JA, Holford TR, Gill TM. Transitions between states of disability and independence among older persons. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:575–584. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays JC, Steffens DC, Flint EP, Bosworth HB, George LK. Does social support buffer functional decline in elderly patients with unipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1850–1855. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hybels CF, Blazer DG, Steffens DC. Predictors of partial remission in older patients treated for major depression: The role of comorbid dysthymia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:713–721. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.8.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S. Assessing self-maintenance: activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983;31:721–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1983.tb03391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempen GIJM, Ranchor AV, van Sonderen E, van Jaarsveld CHM, Sanderman R. Risk and protective factors of different functional trajectories in older persons: Are these the same? J Gerontol Psychol Sci. 2006;61B:P95–P101. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.2.p95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiosses DN, Alexopoulos GS. IADL functions, cognitive deficits, and severity of depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:244–249. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.3.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivela SL, Pahkala K. Depressive disorder as a predictor of physical disability in old age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:290–296. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4930290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Rogers JC, Martire LM, Mulsant BH, Rollman BL, Dew MA, Schulz R, Reynolds CF. The association of late-life depression and anxiety with physical disability: A review of the literature and prospectus for future research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9:113–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Schulz R, Martire L, Zdaniuk B, Glass T, Kop WJ, Jackson SA, Reynolds CF. The course of functional decline in older people with persistently elevated depressive symptoms: Longitudinal findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:569–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oslin DW, Streim J, Katz I, Edell WS, TenHave T. Change in disability follows inpatient treatment for late life depression. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:357–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BWJH, Deeg DJH, van Eijk JT, Beekman ATF, Guralnik JM. Changes in depression and physical decline in older adults: a longitudinal perspective. J Affect Disord. 2000;61:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BWJH, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Deeg DJH, Wallace RB. Depressive symptoms and physical decline in community-dwelling older persons. JAMA. 1998;279:1720–1726. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BWJH, Leveille S, Ferrucci L, van Eijk JTM, Guralnik JM. Exploring the effect of depression on physical disability: Longitudinal evidence from the Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1346–1352. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. Statistical Analysis System, Version 9. Cary NC: SAS Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair PA, Lyness JM, King DA, Cox C, Caine ED. Depression and self-reported functional status in older primary care patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:416–419. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Analysis - Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Steffens DC, Hays JC, Krishnan KRR. Disability in geriatric depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;7:34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffens DC, McQuoid DR, Krishnan KR. The Duke Somatic Treatment Algorithm for Geriatric Depression (STAGED) approach. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2002;36:58–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffens DC, McQuoid DR, Krishnan KRR. Partial response as a predictor of outcome in geriatric depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:340–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis LA, Lyness JM, Shields CG, King DA, Cox C. Social support, depression, and functional disability in older adult primary-care patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:265–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gool CH, Kempen GIJM, Penninx BWJH, Deeg DJH, Beekman ATF, van Eijk JTM. Impact of depression on disablement in late middle aged and older persons: results from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt J, Magidson J. Latent GOLD 4.0 User’s Guide. Belmont, Massachusetts: Statistical Innovations, Inc; 2005a. [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK, Magidson J. Technical Guide for Latent GOLD 4.0: Basic and Advanced. Belmont Massachusetts: Statistical Innovations, Inc; 2005b. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, van Belle G, Kukull WB, Larson EB. Predictors of functional change: A longitudinal study of nondemented people aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1525–1534. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]