Abstract

Evidence in support of the classical lipid raft hypothesis has remained elusive. Data suggests that transmembrane proteins and the actin-containing cortical cytoskeleton can organize lipids into short-lived nanoscale assemblies that can be assembled into larger domains under certain conditions. This supports an evolving view in which interactions between lipids, cholesterol, and proteins create and maintain lateral heterogeneity in the cell membrane.

Introduction and context

Differential lipid composition between the apical and basolateral membrane domains of epithelial cell plasma membranes [1,2] made it clear that membrane lipids are not laterally distributed in a homogeneous fashion. The lipid raft hypothesis was developed to explain lateral separation of bilayer lipids, and this idea quickly found applications in viral budding, endocytosis, and signal transduction (reviewed in [3]). In model membranes, lipids can separate into microscopically resolvable raft-like domains [4]. Plasma membrane surrogates formed by chemical membrane blebbing or cell swelling procedures also show phase behaviour [5-8]. Similar domains are not evident upon direct observation of unperturbed plasma membranes in living cells, but the non-equilibrium nature of cell membranes, including endocytosis, exocytosis, and other motile processes, may prevent overt phase separation. Likewise, quantitative analysis of lipid-anchored protein and lipid diffusion in cell membranes by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP), Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET), and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) [9-11] indicated that rafts in the plasma membrane of resting cells must be very small or ephemeral (or both), forcing an evolution of the lipid raft hypothesis. These tiny clusters do not represent lipid phase separations but are probably short-range ordering imposed upon lipids by transmembrane proteins and cortical actin structures. Thus, the current challenge for the field is to understand the interplay between protein and lipid that converts the exceedingly small, unstable clusters of components into larger, more stable membrane microdomains required for function [3,12].

Major recent advances

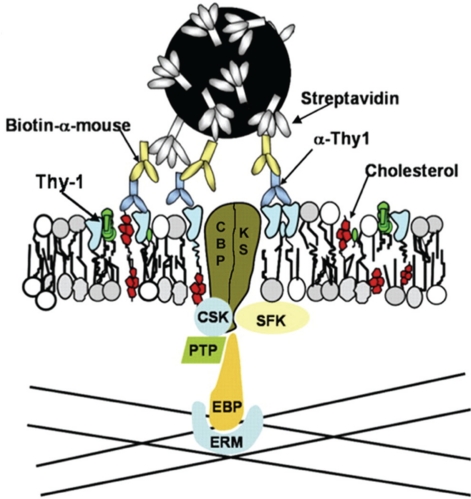

The recent development of sensitive quantitative microscopy methods has advanced our knowledge of lipid dynamics in resting cells. The diffusion of raft lipids (e.g., sphingomyelin) and non-raft lipids (e.g., phosphatidylethanolamine) was measured by an elegant FCS technique within regions as small as 30 nm in diameter using stimulation emission depletion fluorescence microscopy. The results indicate that raft lipids, but not non-raft lipids, are indeed preferentially trapped, albeit for short distances (<20 nm) and for short periods (10-20 ms) [13]. HomoFRET measurements, combining FRAP, emission anisotropy, and theoretical model fitting to test models of lateral organization in the membrane, were used determine the degree of clustering of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins in the plasma membrane [14,15]. The formation of GPI-anchored protein nanoclusters (of ~4 molecules or even less) [14] is an active process involving both actin and myosin, and these nanoclusters are nonrandomly distributed into larger domains of <450 nm [15]. Additionally, high-speed single-particle tracking (50 kHz) revealed that GPI-anchored proteins, along with other membrane proteins, undergo rapid hop diffusion between 40 nm actin-regulated compartments, with a compartment dwell time of 1-3 ms on average [16]. However, when GPI-anchored proteins were deliberately cross-linked by gold or quantum dot particles, they underwent transient confinement or ‘STALL’ (stimulation-induced temporary arrest of lateral diffusion) from a cholesterol-dependent nanodomain in a Src family kinase mediated manner [17-19]. A recent study identified a transmembrane protein (carboxyl-terminal Src kinase [Csk]-binding protein) involved in the linkage between the particle-cross-linked GPI-anchored protein, Thy1, and the cytoskeleton (Figure 1) [20].

Figure 1. EBP50-ERM assembly is the common adaptor complex for linking cholesterol-dependent Thy-1 clusters to the membrane apposed cytoskeleton.

The glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored protein Thy-1 engages membrane lipids and proteins for transmembrane signaling. Thy-1 crosslinking by streptavidin-coated quantum dots aggregates GPI lipid tails in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane in a cholesterol-dependent manner. Carboxyl-terminal Src kinase (Csk)-binding protein (CBP), a transmembrane protein, is recruited to or captured by Thy-1 clusters along with Src-family kinase substrates (KS). CBP or KS (or both) are phosphorylated by Src-family kinases (SFK), enabling CBP to bind to actin filaments via an EBP50-ERM (ezrin/radixin/moesin-binding phosphoprotein 50-ezrin/radixin/moesin) adaptor linkage resulting in a transient anchorage. When either CBP or the adaptors are dephosphorylated by an unspecified protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) the anchorage is terminated. Image adapted from [20]; Chen et al., J Cell Sci 2009.

Larger microdomains involve raft lipids and specific membrane proteins. The lipid envelope of influenza and HIV virions, but not those of the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) or Semliki Forest virus (SFV), is enriched in raft-like lipids, leading to the notion that these viruses bud from lipid microdomains in the plasma membrane [21-25]. By contrast, the lipidomes of VSV and SFV are very similar to each other and to that of the plasma membrane suggesting that these viruses do not select or generate lipid raft domains for budding [25].

The protein and lipid environment of the budding domains of hemagglutinin (HA) and HIV has been the source of several recent papers examining the process of viral budding using quantitative live-cell imaging techniques. Influenza buds from HA clusters (ranging up to micrometers in diameter) [26] regulated by HA transmembrane region length and palmitoylation [27]. Recent fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM)-FRET experiments in living cells indicate that HA colocalizes with lipid microdomain markers, further supporting the role of lipid-protein interactions in influenza virus budding [28,29]. Proton magic angle spinning nuclear magnetic resonance was used to detect a minor fraction (~10-15%) of liquid-ordered membrane phospholipids in HA virions and virion lipid extracts at 37°C. While lipid ordering increased at lower temperatures, it was not required for virion fusion with target membranes [30].

Progressive recruitment of cytoplasmic HIV-1 Gag to the membrane, via post-translational acyl lipid modification and PIP2/basic residue interactions, forms membrane domains that culminate in virion budding [31-33]. While the HIV-1 lipid envelope composition indicates enrichment in lipids and proteins associated with ‘rafts’ [21], paradoxically, one report has failed to observe an enrichment of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-GPI at Gag domains in living cells [32], suggesting that the local lipid microenvironment may not exactly parallel the classic raft lipid composition. Recent work has implicated the tetraspanin family of proteins in Gag domain formation and function. Tetraspanins, a widely expressed and highly conserved class of transmembrane proteins (reviewed in [34]), form tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs) through lateral tetraspanin-tetraspanin interactions and binding to non-tetraspanin membrane proteins. HIV-1 Gag is targeted to TEMs and virus buds from these domains [35,36]. Tetraspanins can be palmitoylated [37] and the lipid environment within TEMs contains cholesterol, but GPI-anchored proteins and caveolin are not enriched in TEMs (reviewed in [38]). Recently, cholesterol and tetraspanin palmitoylation were implicated in the confined diffusion and co-diffusion (of two tetraspanin molecules) of the tetraspanin CD9 [39]. Tetraspanins appear to induce order in the plasma membrane by virtue of protein clustering, but they likely also stabilize lipid microenvironments in the plasma membrane allowing for lateral organization of HIV-1 Gag and virion budding.

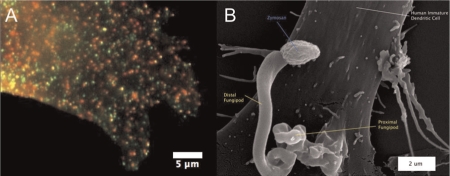

Some lectin-based membrane domains form in the absence of post-translational lipid modifications or known lipid binding activity. Dendritic cell-specific intracellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN), a tetrameric C-type lectin with affinity for high-mannose glycans, forms microdomains on the plasma membrane [40-42] that serve as high-avidity binding sites for numerous pathogens. A previous report suggested that DC-SIGN interacts with lipid rafts [40], but this was based on detergent insolubility and cholera toxin colocalization assays, which generally do not faithfully report on intrinsic membrane lateral heterogeneity. Also, DC-SIGN domains do not depend on cholesterol (unpublished data). Surprisingly, DC-SIGN domains do not recover following photobleaching [42]. This result implies that DC-SIGN within domains does not exchange with the surrounding membrane. The source of this stability remains a mystery, and its cause may not reside in the membrane-apposed cytoskeleton but in extracellular cross-linking factors such as galectins (reviewed in [43]). DC-SIGN membrane domains that are multiplexed with another C-type lectin, CD206 (unpublished data), appear to mediate the formation of fungipods, novel cellular protrusive structures involved in fungal recognition by dendritic cells (Figure 2) [44]. Thus, the lateral heterogeneity in membranes provided by rafts and other microdomains continues to provide surprising functional consequences.

Figure 2. C-type lectin domains and fungipod formation.

C-type lectins (CLRs) form a type of plasma membrane domain that is not dependent on cholesterol. (A) Plasma membrane domains containing mixtures (yellow) of dendritic cell-specific intracellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin (DC-SIGN) (green) and CD206 (red) are observed on a monocyte-derived dendritic cell (DC) by immunofluorescence. DC-SIGN domains are known sites of binding and entry for a range of pathogens including HIV-1. (B) Yeast cell wall material is sensed by these CLR membrane domains, triggering a unique protrusive response, the fungipod. The image shows an example of a DC fungipod formed via CD206 ligation by a fixed Saccharomyces cerevisiae particle (zymosan), visualized by scanning electron microscopy (9500×). Figure 2B was reproduced from [44], Neumann & Jacobson, PLoS Pathog 2010.

Future directions

A variety of membrane domain forming systems have a wide gamut of lipid and protein constituents and possess a correspondingly broad range of functions. Recent advances have shown that preferential lipid trapping or confinement in the resting plasma membrane occurs only on very small spatiotemporal scales. Critical attention must be paid when determining if and when such confinement becomes biologically meaningful for processes such as endocytosis and signal transduction. While lipid ordering can be stabilized by oligomerization of membrane-associated proteins (i.e., GM1 crosslinking, influenza HA clustering), the lipids in these domains may still exchange between domain and surrounding membranes, making even these stabilized raft-like domains dynamic environments. At what point does a membrane domain become stable enough to be biologically relevant? What is the range of protein and lipid turnover rates seen in membrane domains and are there different turnover rates for each constituent? It is likely that a spectrum of membrane microdomains exists with different compositions and physical characteristics suited to their diverse purposes. The lipid species and their ordering within raft-like complexes appear to be key factors in determining intradomain cohesiveness and resultant domain size and lifetime.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM 41402 and the Cell Migration Consortium Grant GM 064346.

Abbreviations

- DC-SIGN

dendritic cell-specific intracellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin

- FCS

fluorescence correlation spectroscopy

- FRAP

fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

- FRET

Förster resonance energy transfer

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- HA

hemagglutinin

- PIP2

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- SFV

Semliki Forest virus

- TEM

tetraspanin-enriched microdomain

- VSV

vesicular stomatitis virus

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found at: http://f1000.com/reports/b/2/31

References

- 1.Kawai K, Fujita M, Nakao M. Lipid components of two different regions of an intestinal epithelial cell membrane of a mouse. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;369:222–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Meer G, Simons K. Viruses budding from either the apical or the basolateral plasma membrane domain of MDCK cells have unique phospholipid compositions. EMBO J. 1982;1:847–52. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lingwood D, Simons K. Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science. 2010;327:46–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1174621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.0 Must ReadEvaluated by Kenneth Yamada 20 Jan 2010

- 4.Dietrich C, Bagatolli LA, Volovyk ZN, Thompson NL, Levi M, Jacobson K, Gratton E. Lipid rafts reconstituted in model membranes. Biophys J. 2001;80:1417–28. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76114-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veatch SL, Cicuta P, Sengupta P, Honerkamp-Smith A, Holowka D, Baird B. Critical fluctuations in plasma membrane vesicles. ACS Chem Biol. 2008;3:287–93. doi: 10.1021/cb800012x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumgart T, Hammod AT, Sengupta P, Hess ST, Holowka DA, Baird BA, Webb WW. Large-scale fluid/fluid phase separation of proteins and lipids in giant plasma membrane vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3165–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611357104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 3.0 RecommendedEvaluated by Ken Jacobson 31 Jul 2007

- 7.Sengupta P, Hammond A, Holowka D, Baird B. Structural determinants for partitioning of lipids and proteins between coexisting fluid phases in giant plasma membrane vesicles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lingwood D, Ries J, Schwille P, Simons K. Plasma membranes are poised for activation of raft phase coalesence at physiological temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10005–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804374105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenworthy AK, Nichols BJ, Remmert CL, Hendrix GM, Kumar M, Zimmerberg J, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Dynamics of putative raft-associated proteins at the cell surface. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:735–46. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 3.0 RecommendedEvaluated by Peter Ekblom 07 Jul 2004

- 10.Glebov OO, Nichols BJ. Lipid raft proteins have a random distribution during localized activation of the T-cell receptor. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:238–43. doi: 10.1038/ncb1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.5 Must ReadEvaluated by Emanuela Handman 15 Mar 2004, Akihiro Kusumi 06 Apr 2004, Pamela Schwartzberg 07 Jul 2004

- 11.Lenne PF, Wawrezinieck L, Conchonaud F, Wurtz O, Boned A, Guo XJ, Rigneault H, He HT, Marguet D. Dynamic molecular confinement in the plasma membrane by microdomains and the cytoskeleton meshwork. EMBO J. 2006;25:3245–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.6 Must ReadEvaluated by Peter Mayinger 31 Jul 2006, Gerrit van Meer 10 Oct 2006, Akihiro Kusumi 30 Oct 2006, Ken Jacobson 23 Feb 2007

- 12.Jacobson K, Mouritsen OG, Anderson RG. Lipid rafts: at a crossroad between cell biology and physics. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:7–14. doi: 10.1038/ncb0107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eggeling C, Ringemann C, Medda R, Schwarzmann G, Sandhoff K, Polyakova S, Belov VN, Hein B, von Middendorff C, Schönle A, Hell SW. Direct observation of the nanoscale dynamics of membrane lipids in a living cell. Nature. 2009;457:1159–62. doi: 10.1038/nature07596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.4 Must ReadEvaluated by Akihiro Kusumi 30 Mar 2009, Lukas Tamm 24 Jun 2009

- 14.Sharma P, Varma R, Sarasij RC, Ira, Gousset K, Krishnamoorthy G, Rao M, Mayor S. Nanoscale organization of multiple GPI-anchored proteins in living cell membranes. Cell. 2004;116:577–89. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 8.0 ExceptionalEvaluated by Annette Dolphin 24 Feb 2004, Akihiro Kusumi 24 Mar 2004

- 15.Goswami D, Gowrishankar K, Bilgrami S, Ghosh S, Raghupathy R, Chadda R, Vishwakarma R, Rao M, Mayor S. Nanoclusters of GPI-anchored proteins are formed by cortical actin-driven activity. Cell. 2008;135:1085–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umemura YM, Vrjic M, Nishimura SY, Fujiwara TK, Suzuki KG, Kusumi A. Both MHC class II and its GPI-anchored form undergo hop diffusion as observed by single-molecule tracking. Biophys J. 2008;95:435–50. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.123018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y, Thelin WR, Yang B, Milgram SL, Jacobson K. Transient anchorage of cross-linked glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins depends on cholesterol, Src family kinases, caveolin, and phosphoinositides. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:169–78. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 3.0 RecommendedEvaluated by Akihiro Kusumi 27 Oct 2006

- 18.Suzuki KG, Fugiwara TK, Sanematsu F, lino R, Edidin M, Kusumi A. GPI-anchored receptor clusters transiently recruit Lyn and G alpha for temporary cluster immobilization and Lyn activation: single-molecule tracking study 1. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:717–30. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.0 Must ReadEvaluated by Ken Jacobson 30 Jul 2007

- 19.Suzuki KG, Fujiwara TK, Edidin M, Kusumi A. Dynamic recruitment of phospholipase C gamma at transiently immobilized GPI-anchored receptor clusters induces IP3-Ca2+ signalling: single-molecule tracking study 2. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:731–42. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.0 Must ReadEvaluated by Ken Jacobson 30 Jul 2007

- 20.Chen Y, Veracini L, Benistant C, Jacobson K. The transmembrane protein CBP plays a role in transiently anchoring small clusters of Thy-1, a GPI-anchored protein, to the cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3966–72. doi: 10.1242/jcs.049346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen DH, Hildreth JE. Evidence for budding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 selectively from glycolipid-enriched membrane lipid rafts. J Virol. 2000;74:3264–72. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.7.3264-3272.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aloia RC, Tian H, Jensen FC. Lipid composition and fluidity of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope and host cell plasma membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:5181–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheiffele P, Rietveld A, Wilk T, Simons K. Influenza viruses select ordered lipid domains during budding from the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2038–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brugger B, Glass B, Haberkant P, Leibrecht I, Wieland FT, Krausslich HG. The HIV lipidome: a raft with an unusual composition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2641–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511136103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.0 Must ReadEvaluated by Etienne Joly 04 Apr 2006

- 25.Kalvodova L, Sampaio JL, Cordo S, Ejsing CS, Shevchenko A, Simons K. The lipidomes of vesicular stomatitis virus, semliki forest virus, and the host plasma membrane analyzed by quantitative shotgun mass spectrometry. J Virol. 2009;83:7996–8003. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00635-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.0 Must ReadEvaluated by Lynn Enquist 13 Aug 2009

- 26.Hess ST, Gould TJ, Gudheti MV, Maas SA, Mills KD, Zimmerberg J. Dynamic clustered distribution of hemagglutinin resolved at 40 nm in living cell membranes discriminates between raft theories. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17370–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708066104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.0 Must ReadEvaluated by Ken Jacobson 20 Dec 2007

- 27.Takeda M, Leser GP, Russell CJ, Lamb RA. Influenza virus hemagglutinin concentrates in lipid raft microdomains for efficient viral fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14610–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235620100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engel S, Scolari S, Thaa B, Krebs N, Korte T, Herrmann A, Veit M. FLIM-FRET and FRAP reveal association of influenza virus haemagglutinin with membrane rafts. Biochem J. 2010;425:567–73. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scolari S, Engel S, Krebs N, Plazzo AP, De Almeida RF, Prieto M, Veit M, Herrmann A. Lateral distribution of the transmembrane domain of influenza virus hemagglutinin revealed by time-resolved fluorescence imaging. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:15708–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900437200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polozov IV, Bezrukov L, Grawrisch K, Zimmerberg J. Progressive ordering with decreasing temperature of the phospholipids of influenza virus. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:248–55. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jouvenet N, Bieniasz PD, Simon SM. Imaging the biogenesis of individual HIV-1 virions in live cells. Nature. 2008;454:236–40. doi: 10.1038/nature06998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.0 Must ReadEvaluated by Ken Jacobson 18 Jun 2008

- 32.Ivanchenko S, Godinez WJ, Lampe M, Krausslich HG, Eils R, Rohr K, Brauchle C, Muller B, Lamb DC. Dynamics of HIV-1 assembly and release. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000652. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saad JS, Miller J, Tai J, Kim A, Ghanam RH, Summers MF. Structural basis for targeting HIV-1 Gag proteins to the plasma membrane for virus assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11364–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602818103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.0 Must ReadEvaluated by Paul Bieniasz 20 Oct 2006

- 34.Hemler ME. Tetraspanin functions and associated microdomains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:801–11. doi: 10.1038/nrm1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nydegger S, Khurana S, Krementsov DN, Foti M, Thali M. Mapping of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains that can function as gateways for HIV-1. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:795–807. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 6.0 Must ReadEvaluated by Ken Jacobson 15 Jun 2006

- 36.Jolly C, Sattentau QJ. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly, budding, and cell-cell spread in T cells take place in tetraspanin-enriched plasma membrane domains. J Virol. 2007;81:7873–84. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01845-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Claas C, Stipp CS, Hemler ME. Evaluation of prototype transmembrane 4 superfamily protein complexes and their relation to lipid rafts. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7974–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008650200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le Naour F, Andre M, Boucheix C, Rubinstein E. Membrane microdomains and proteomics: lessons from tetraspanin microdomains and comparison with lipid rafts. Proteomics. 2006;6:6447–54. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Espenel C, Margeat E, Dosset P, Arduise C, Le Grimellec C, Royer CA, Boucheix C, Rubinstein E, Milhiet PE. Single-molecule analysis of CD9 dynamics and partitioning reveals multiple modes of interaction in the tetraspanin web. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:765–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 3.0 RecommendedEvaluated by Akihiro Kusumi 02 Sep 2008

- 40.Cambi A, de Lange F, van Maarseveen NM, Nijhuis M, Joosten B van Dijk EM, de Bakker BI, Fransen JA, Bovee-Geurts PH, van Leewen FN, Van Hulst NF, Figdor CG. Microdomains of the C-type lectin DC-SIGN are portals for virus entry into dendritic cells. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:145–55. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200306112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koopman M, Cambi A, de Bakker BI, Joosten B, Figdor CG, van Hulst NF, Garcia-Parajo MF. Near-field scanning optical microscopy in liquid for high resolution single molecule detection on dendritic cells. FEBS Lett. 2004;573:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neumann AK, Thompson NL, Jacobson K. Distribution and lateral mobility of DC-SIGN on immature dendritic cells--implications for pathogen uptake. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:634–43. doi: 10.1242/jcs.022418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grigorian A, Torossian S, Demetriou M. T-cell growth, cell surface organization, and the galectin-glycoprotein lattice. Immunol Rev. 2009;230:232–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neumann AK, Jacobson K. A novel pseudopodial component of the dendritic cell anti-fungal response: the fungipod. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000760. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; F1000 Factor 3.0 RecommendedEvaluated by Alan Fanning 26 Feb 2010