Abstract

Motivation: The anatomy of model species is described in ontologies, which are used to standardize the annotations of experimental data, such as gene expression patterns. To compare such data between species, we need to establish relations between ontologies describing different species.

Results: We present a new algorithm, and its implementation in the software Homolonto, to create new relationships between anatomical ontologies, based on the homology concept. Homolonto uses a supervised ontology alignment approach. Several alignments can be merged, forming homology groups. We also present an algorithm to generate relationships between these homology groups. This has been used to build a multi-species ontology, for the database of gene expression evolution Bgee.

Availability: download section of the Bgee website http://bgee.unil.ch/

Contact: marc.robinson-rechavi@unil.ch

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Databases dedicated to model species rely on the usage of ontologies, for example the zebrafish anatomy for ZFIN (Sprague et al., 2006), or the Mouse gross anatomy and development (Baldock et al., 2003). Such ontologies of anatomy and development facilitate the organization of functional data pertaining to a species. For example, all gene expression patterns described in ZFIN are annotated using the zebrafish anatomical ontology. A list of such ontologies is kept on the Open Biomedical Ontologies (OBO) website (Smith et al., 2007).

To pool the experimental data from different model species, we need to encode corresponding information between ontologies which describe different anatomies (e.g. zebrafish and human). For example, we are interested in integrating and comparing gene expression patterns between several species (Bastian et al., 2008). The most widely accepted criterion to make such comparisons in biology is homology (Hall, 1994; Hossfeld and Olsson, 2005). When we compare two elements, whether or not they are derived from the same ancestral element defines our expectation of similarity between them, and the interpretation of differences. For example, if a chicken wing is not homologous to a fly wing, we do not expect the same underlying structures, and similarities can be attributed to functional convergence. Whereas the chicken wing is homologous (as a limb) to the human arm, thus we do expect the same underlying structures, and differences can be attributed to divergent evolution. There are different definitions of homology (Roux and Robinson-Rechavi, 2010), and our algorithm does not in itself impose one on the user. We do recommend choosing an explicit definition and using it consistently throughout the analysis.

In practice, hundreds of terms must be compared between ontologies that may differ both in the actual biology modeled (i.e. a fish is not a mammal) and in the representation used. Although a purely manual annotation of homologies is possible, it would be too time consuming to be done for all terms between several divergent species. Kruger et al. (2007) have used a manual approach to find similarities between simplified anatomy ontologies for human and mouse. As both are mammals, they share most structures and terminology. There are also on-going efforts to integrate anatomical ontologies (Haendel et al., 2008; Washington et al., 2009), which are often geared towards the comparison of phenotypes (Lussier and Li, 2004). As far as we know, the question of using homology to align anatomical ontologies has never been explicitly addressed.

Since the problem is to find correspondences between the concepts of two ontologies, we draw on methods from ‘schema matching’, or ‘ontology alignment’ (Euzenat and Shvaiko, 2007; Lambrix and He, 2008). As opposed to more generalist solutions, we present a algorithm which is specialized in the alignment of anatomical ontologies. The specificities of these ontologies include high redundancy of terms, and few types of relations. Finally, a specific issue is that structures which have the same name and are related to similar concepts may not be homologous. This is the case of the insect eye and the mammalian eye. While some underlying molecular mechanisms are similar, these structures evolved independently and are not considered homologous (discussed in Hall, 1994; Shubin et al., 2009). Unsupervised alignment algorithms would misleadingly align such similarities; this is for instance the case for the LOOM software used on the NCBO portal (Ghazvinian et al., 2009).

In principle, an alignment algorithm should aim at finding the largest number of true positives, while avoiding false positives. In practice, our experience is that the size and structure of anatomical ontologies leads to very large numbers of false positives if a naive approach is taken (i.e. common words). Thus, the basic aim of Homolonto is to propose in priority to the user the best candidate pairs of homologs, and avoid the need to consider many irrelevant pairs.

2 SYSTEMS AND METHODS

Homolonto is implemented in Java. Ontologies are read in the OBO format (Smith et al., 2007). Homolonto is freely available in the download section of the Bgee website (http://bgee.unil.ch/).

3 ALGORITHM

3.1 Principle

Ontology alignment is the process of determining correspondences between ontology concepts. We present our approach based on the classification of ontology matching systems proposed by Euzenat and Shvaiko (2007; Shvaiko and Euzenat, 2005).

Biological ontologies simplify some aspects relative to the general case. The types of concepts (e.g. anatomical structures) and the relationships (e.g. part_of) are known in advance, and known to be common between the ontologies to align. Moreover, in the present implementation we only seek to establish one type of relation, homology.

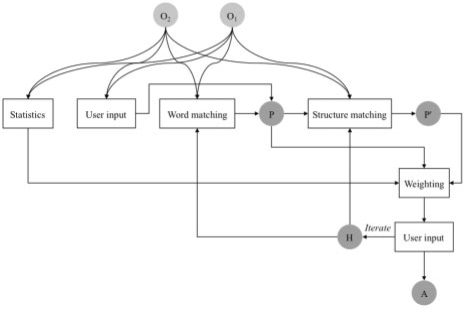

Our algorithm can be described as a composite system (Fig. 1), using: (i) language-based comparison of names with tokenization (element level, syntactic technique); (ii) graph-based matching of children of elements (structure level, syntactic technique); (iii) data analysis, e.g. statistics on word occurrence (structure level, syntactic technique); (iv) external input from the user (element level, external technique; classification following Euzenat and Shvaiko, 2007). We combine the results in parallel, as opposed to in sequence, by using a sum of scores from different techniques. Thus, we make use both of schema and element level information. The algorithm produced in a first step anchors at the element level, generated by language technique, and potentially by the user (external), then uses information from the schema, the elements, and user input, to improve the alignment based on these anchors.

Fig. 1.

Homolonto pairwise alignment architecture. O1 and O2 are ontologies to align. P and P′ are lists of propositions. H is a list of validated homologies (invalidation information). A is the final alignment, generated when the user chooses to stop iterations. User input appears twice: to propose original pairings, and to validate propositions.

Importantly, each proposition of homology between elements must be validated by the user (external input), to take into account such cases as the eye, discussed in the ‘Introduction’ section. Thus our process is a supervised one.

Finally, we note that the alignment we obtain is of the form many to many, not one to one.

3.2 Definitions

A central concept in our algorithm is that of a ‘proposition’ (similar to ‘suggestion’ in Lambrix and He, 2008). A proposition is a pair of terms (also called ‘class’ in OWL) from the two ontologies for which a score has been computed. This may have been done based on homonymy (common words) of the term names (also called ‘class label’ in OWL), or propagation through the ontology. It is important to note (i) that not all possible propositions (i.e. pairs of terms) are created during the alignment, and (ii) that the list of propositions evolves during iterations of the algorithm.

For performance, our algorithm is not symmetric. Propositions are managed relative to one ontology, ‘to align’, which is being aligned to the ‘reference ontology’ (the one loaded first by the user). This allows us to store explicitly the information that term A of the ontology to align has two propositions, with term X and with term Y, of the reference ontology. If X has propositions not only with A but also with B of the ontology to align, this will not be taken into account explicitly.

3.3 Algorithm

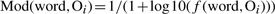

- Computing word specific scores: score modifiers are computed for all words of the ontologies being aligned. Each word present at least once in both ontologies being aligned (O1 and O2) is given a score modifier based on its number of occurrences f (word, O):

(1)

(2) -

Starting list of propositions (P in Fig. 1): to initialize the algorithm we define first obvious similarities between the terms of the ontologies to align. Based on the assumption that two structures that have the same name are likely homologous, the initial propositions are formed of terms with identical names. For example, ‘optic cup’ of ZFA (zebrafish, Table 1) and ‘optic cup’ of EHDAA (human, Table 1) will form a proposition. But ‘ventricle’ and ‘cardiac ventricle’ will not. In this process, we also consider the synonym field of the terms. For example the ZFA term ‘melanocyte’ (synonym ‘melanophore’) will form a proposition with the term ‘melanophore’ (synonym ‘melanocyte’) from XAO (Xenopus, Table 1).

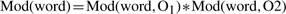

Each pair of names n1, n2, is given a base score, dependent on the words shared:

where |n| is the number of words in n, |n1 ∩ n2| is the number of words shared by n1 and n2, and max(Mod(word)) is computed over all shared words. In the starting list, |n1 ∩ n2| = |n1| = |n2| by definition, but this is not the case at further iterations of the algorithm.

(3) The comparison of terms names is intentionally quite basic, and does not take advantage of, e.g. etymology of words. In our experience, terms names used in anatomical ontologies are similar enough that more sophisticated approaches generate too many false positives, without improving the recovery of true positives.

Initial propagation step: the score of these propositions is propagated between neighbors. This initial propagation is bidirectional, and limited to already defined propositions. For example, the score of the ‘optic cup’ pair is added to the score of the ‘eye’ pair, as ‘optic cup’ is part of ‘eye’, and both pairs are initial propositions. Symmetrically the score of the ‘eye’ pair is added to the ‘optic cup’ pair. But the score of ‘eye’ is not propagated to e.g. the pairing of ‘visual system’ (ZFA parent of ‘eye’) with ‘sensory organ’ (EHDAA parent of ‘eye’), because this pair is not an initial proposition. The aim of this step is to increase the score of the most likely homologs (resulting in P′ in Fig. 1).

Cleaning the initial proposition list: the design of some ontologies may generate many false positives, typically through repetition of the same name as a child of diverse structures (e.g. 76 occurrences of ‘mesenchyme’ in EHDAA). To avoid this, if a term is a member of several propositions with different scores, we initially keep only the best scoring proposition. If there are more than five highest scoring propositions for a given term, the algorithm removes all propositions for this term.

-

Evaluation step: each proposition is presented to the user, in descending order of scores. The user has four options for each proposition: (i) validation as homology; this excludes further pairings of the form sibling of term A with term B, or A with sibling of B. (ii) Validation as ‘partial homology’; this allows further pairing of siblings of A with B, or of A with siblings of B. These may be due to differences in ontology representation. This is also useful to manage serial homology: all somites may be defined as homologous inside one individual. (iii) Invalidation. (iv) Delay decision concerning this proposition.

The user may chose to evaluate any number of propositions before provoking the computation step. It is recommended in most cases to proceed to computation (‘iterate’ in the graphical user interface, GUI) after every decision.

-

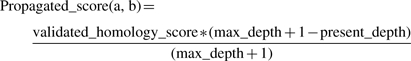

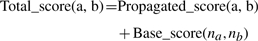

Computation step: if one of the terms of a validated pair is already a member of an homology group, then the other term is added to the homology group. Otherwise, a new homology group is created, containing both terms of the validated pair (H in Fig. 1). The information of homology is propagated through the hierarchy by the use of a validated homology score (Equation 4). The underlying idea is that if two terms A and B are homologous, then one of the children of A is probably homologous to one of the children of B. During the propagation the validated homology score is added to the base score (Equation 3) of pairs of terms:

(4)

where na is the name of term a. In the present implementation, the propagation depth is 1, and the validated homology score is 1.5 times the base homonymy score. For pairs of terms which are not yet a proposition, a new proposition is created, and the base score is computed. This will include cases of partial homonymy, for which Equation 3 down weights names which share a lower proportion of words. Pairs which have been previously invalidated by the user will not receive a propagated score, and will remain invalidated.

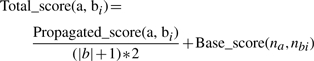

(5a) To down weight potential false positives due to validation of terms with many children, the propagated score is reduced proportionally to the number of new propositions for each term of the ontology to align (Equation 5b).

where a is a term of the ontology to align, bi is a term of the reference ontology, and |b| is the number of new propositions for term a. When a proposition (a, bi) is invalidated, |b| is updated, and the Total score(a, bi) increases for the remaining propositions.

(5b) When the terms of an invalidated proposition share common words, then the score modifiers of all shared words is diminished (Equation 6). As this is repeated, words which tend to generate false positives will be increasingly down weighted.

(6) Iteration: evaluation of propositions (Step 5), ordered by total score (base score + propagated score), and computation (Step 6), is repeated until the user decides to terminate, or no more propositions are generated (resulting in the alignment A in Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the alignments discussed

| Zebrafish | Xenopus | Human | Mouse | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontologya | ZFA | XAO | EHDAA | EMAPA |

| Number of terms | 1974 | 569 | 2327 | 3525 |

| with synonyms | 1080 | 122 | 0 | 0 |

| with definitions | 772 | 186 | 0 | 0 |

| Number of validationsb | 189 | 1959 | ||

| Number of invalidations | 543 | 1003 | ||

| Number of unique terms aligned | 183 | 182 | 1541 | 1754 |

aReferences for the ontologies aligned are: ZFA (Sprague et al., 2006) (version of 24:10:2007); XAO (Bowes et al., 2008) (version of 07:11:2007); EHDAA (Aitken, 2005; Hunter et al., 2003) (version of 08:04:2005); EMAPA (Aitken, 2005; Baldock et al., 2003) (version of 08:04:2005).

bIncluding ‘partial’ validations.

4 IMPLEMENTATION AND GUI

Homolonto displays the input OBO ontologies under a tree representation form. The user may browse the ontology, and a basic ‘find’ tool has been implemented. Before starting the alignment algorithm, the user has the possibility to manually specify homology relations. This allows potential anchoring of structures with very different names between species, based on known biology (e.g. limb and fin). Once the alignment algorithm is run, a new window opens and displays the best propositions, one at a time, in order of score. For each term of a proposition, the parents are shown for two levels, to help the decision. Clicking on a term identifier opens the first occurrence of that term in the ontology browser window, where the user can check for more information (e.g. synonyms, develops_from relations). Decisions can be annotated with comments and with a link, similar to the ‘dbxref’ field of OBO-Edit (Day-Richter et al., 2007).

To facilitate alignment of large ontologies, keyboard shortcuts are implemented for the most common decisions: enter key = validation as homology plus computation and iteration; escape key = invalidate plus computation and iteration; right and left arrows to see the next and previous propositions without computation.

When several pairwise alignments have been conducted, Homolonto offers a function to reconcile them, if they share a common ontology. Thus if both pairs human and mouse, and human and zebrafish, have been aligned, the triplets human - mouse - zebrafish are created. This means that the number of propositions to validate does not need to increase in O(N2). Rather, each new ontology must be fully aligned to only one already aligned ontology, then the missing homologies must be informed. A judicious choice of the initial pairwise alignment should minimize these missing homologies.

5 RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN HOMOLOGY GROUPS

Homolonto is used to generate pairwise homology relationships between anatomical ontologies. As homology relationships are transitive, Homolonto offers the option to merge these pairwise alignments into homologous organs groups (HOGs). This generates both the HOGs, and the mapping of species-specific anatomical structures to these HOGs. HOGs then need to be structured as an ontology to allow reasoning on them. This means that, at a minimum, relationships amongst them have to be designed. Another algorithm has thus been developed to infer relationships between HOGs.

Initial Step: all possible paths between HOGs are retrieved. For instance, if an anatomical structure ‘a’, mapped to the HOG ‘A’, has a part_of relationship to the anatomical structure ‘b’, mapped to the HOG ‘B’, then a putative part_of relationship is defined between HOGs ‘A’ and ‘B’. Relationships between HOGs are often indirect (e.g. structure ‘a’, mapped to HOG ‘A’, part_of structure ‘c’, part_of structure ‘b’, mapped to HOG ‘B’). If the first relation (the relation ‘outgoing’ from the child HOG, ‘A’ in the previous example) and the last relation (the relation ‘incoming’ to the parent HOG, ‘B’ in the previous example) are of the same type (e.g. part_of, is_a), then the putative relationship is defined as this type. Otherwise, the relationship is defined as the SKOS type broader_than (http://www.w3.org/TR/2008/WD-skos-reference-20080829/).

Skipping relations from non-trusted ontologies: some ontologies do not follow the OBO principles, and implement for instance only one type of relation amongst all concepts [e.g. EV (Kelso et al., 2003) only uses is_a relationships]. The user may choose to not use these ontologies to define relation types. All the putative relations inferred by these ontologies at Step 1 are then set as broader_than. But the final relation type between these HOGs can still be inferred thanks to other ontologies.

Skipping relations defined by too few ontologies: if the proportion of ontologies defining a relation, compared to the total number of ontologies involved in the creation of the HOGs, is below a threshold defined by the user (‘ontology coverage’), then the relation is defined to the type broader_than, and the algorithm stops examining relations between these HOGs.

Defining within-ontology agreement: several anatomical structures from the same ontology can belong to the same HOG. This can generate a within-ontology conflict for defining a relation type. For instance, structures ‘a’ and ‘b’ allow to define a putative part_of relationship between HOGs ‘A’ and ‘B’, while structures ‘a′’ and ‘b′’, belonging to the same ontology, define a putative is_a relationship between these HOGs. The algorithm then calculates, for each relation type, the proportion that the number of paths defining this relation type represents, compared to the total number of paths between these two HOGs for this ontology. If, for a type, this proportion exceeds a threshold (‘within-ontology agreement’), defined by the user and at least >0.5, then this relation type is attributed for this ontology between these HOGs. Otherwise, the relation is defined to the type broader_than for this ontology.

Defining inter-ontology agreement: different ontologies can define different relation types between two related HOGs. This conflict is resolved in the same way as at Step 4, by using a threshold (‘inter-ontology agreement’), defined by the user and at least >0.5.

Removing cyclic relationships: by inferring automatically the relationships between HOGs, cycles may be generated (e.g. HOG ‘A’ part_of HOG ‘B’ part_of HOG ‘A’), whereas an ontology has to be acyclic. If such cycles are detected, the algorithm stops with an error message prompting the user to make a decision: the user has then to manually remove one of the involved relationships.

Removing redundancies: if several relationships are redundant, only the deepest relationship is conserved; for instance, if a HOG ‘A’ has two substructures by a part_of relationship, ‘B’ and ‘C’, and if ‘C’ is also a substructure of ‘B’, then the direct relationship between the HOGs ‘A’ and ‘C’ is removed.

Curation step: a curator can then manually review the broader_than relations, to attribute them to a type defined by the OBO Relation Ontology (Smith et al., 2005). Some custom relationships, not inferred by the algorithm, can also be added at this step.

6 RESULTS

To date, the use of Homolonto, followed by a curation process, has allowed to define 1002 HOGs, involving 4459 structures from seven anatomical ontologies: ZFA (Sprague et al., 2006), EHDAA (Aitken, 2005; Hunter et al., 2003), EV (Kelso et al., 2003), EMAPA (Aitken, 2005; Hunter et al., 2003), MA (Smith et al., 2007), XAO (Bowes et al., 2008) and FBbt (Grumbling et al., 2006). The algorithm to design relationships amongst the HOGs inferred 1411 relations. With the most stringent parameters (ontology coverage = 1, within-ontology agreement = 1, inter-ontology agreement = 1), 222 of them were defined automatically as part_of, 15 as is_a, all the others as broader_than. After curation, there are 1179 part_of and 232 is_a relations. The resulting alignments are used in the database Bgee (Bastian et al., 2008). Thus an important result is that we have been able to implement in a practical manner anatomical homology relationships.

Here, we present, in more detail, two alignments (Table 1): first, zebrafish/Xenopus, which illustrates a best case scenario of two consistent ontologies, conforming to the CARO standards (Haendel et al., 2008), with annotations of synonyms and definitions, and low redundancy. On the other hand, Xenopus (a frog) and zebrafish (a ray-finned fish) present important differences in anatomy. And second, human/mouse which, despite the similarity in anatomy, illustrates a more difficult scenario of large ontologies, with issues such as repetition of names (76 occurrences of ‘mesenchyme’ in human, 93 in mouse), due to splitting of concepts among morphological structures or among developmental stages.

The main observation is that our algorithm is successful at ordering propositions. In the ‘easy’ case of zebrafish/Xenopus (Supplementary Figs S1 and S2), there are only seven invalidated propositions in the first 150 (95% validation). This is followed by a relatively short interval of iterations where validated and invalidated propositions are mixed: 46% of validations between iterations 151 and 200, and 20% between 201 and 250. Further iterations generate mostly invalidated propositions (3% validation from 251 to 735). Thus, 93% of all validations occurred in the first 250 iterations. Looking in more detail, the first propositions are terms which share many children. Thus, the first proposition pairs ‘organism subdivision’ from each ontology, which share four children with identical names (‘head’, ‘trunk’, ‘tail’ and ‘surface structure’). The second proposition pairs two terms which have different names, but are identified readily thanks to their synonyms: XAO:0000023 ‘skin’, synonym ‘integument’ and ZFA:0000368 ‘integument’, synonym ‘skin’ (IDs correspond to the versions used for the alignment; Table 1). The first invalidated proposition (iteration 77) has a peculiar status, since both ontologies include a term ‘unspecified’, which are equivalent but cannot be defined as homologous. The next invalidated proposition (iteration 130) is between XAO:0000313 ‘head somite’ and ZFA:0001462 ‘somite border’. Indeed, early in the iterations, sharing a parent ‘somite’ plus sharing the word ‘somite’ brings a relatively high score. But since propositions based on this are usually invalidated, the word ‘somite’ loses weight (Equation 6), and further propositions based on this similarity receive lower scores. Thus, whereas there are in principle 24 possible propositions between the Xenopus and zebrafish ontologies based on ‘somite’, only 13 were considered in this very thorough alignment (including the validated pair XAO:0000058 ‘somite’—ZFA:0000155 ‘somite’). At the other extreme of the alignment, the last validated propositions (iterations 607–610) concern aortic arches which were named, e.g. ‘aortic arch 4’ in zebrafish, but ‘fourth aortic arch’ in Xenopus. Their low scores were due to the high frequency of the words ‘aortic’ and ‘arch’ in both ontologies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Examples of false positives and false negatives

| Term 1 | Term 2 | Homolonto result | Frequency of shared wordsa |

|---|---|---|---|

| XAO:0000399 tendon fibroblast | ZFA:0009296 perijunctional fibroblast | False positiveb | 3 |

| EMAPA:16370 cardiovascular system (part_of extraembryonic component) | EHDAA:394 cardiovascular system (part_of organ system part_of embryo) | False positiveb | 3 |

| EMAPA:16754 central nervous system (part_of tail) | EHDAA:828 central nervous system (part_of nervous system) | False positiveb | 3 |

| XAO:0000385 pronephric sinus (part_of pronephric kidney) | ZFA:0001557 pronephric glomerulus (part_of pronephros) | False positiveb | 36 |

| XAO:0000119 lung (part_of respiratory system) | ZFA:0000354 gill (part_of respiratory system) | False positiveb | – |

| XAO:0000355 fourth aortic arch | ZFA:0005008 aortic arch 4 | False negativec | 43 |

| EMAPA:17340 right ventricle (part_of ventricle) | EHDAA:1916 right part (part_of ventricle) | False negativec | 67 |

| EMAPA:17853 naso-lacrimal duct (part_of nose) | EHDAA:7837 nasolacrimal duct (part_of nasolacrimal groove) | False negativec | 75 |

| XAO:0000050 mesoderm (part_of embryo) | ZFA:0000041 mesoderm (part_of primary germ layer) | False negatived | 183 |

aSum of frequencies in the two ontologies being compared.

bProposition with a high score between non-homologous structures.

cProposition with a low score between homologous structures.

dNo proposition reported between homologous structures.

The pattern is similar for the human/mouse alignment (Supplementary Fig. S3). In the first 1400 iterations, 99% of propositions are validated. In the next 600 iterations, the figure reduces to 63%, and in the last 962 iterations it falls to 21%. This slower decrease illustrates the complexity of this alignment. Although 2962 iterations may seem large, three points should be noted: (i) this is a worst case scenario, aligning two large anatomical ontologies, which lack important information such as definitions and synonyms, and are not up to recent standards (Haendel et al., 2008). (ii) This represents in our experience only 15 person-days of work, which means an iteration takes on average 2–3 min (on a Dual-core processor at 2.66 GHz, with 2Go of DDR2 memory). This is possible because many answers are obvious to the annotator in context of the information provided by the graphical user interface. For example, while the term EMAPA:18280 ‘intrinsic’ may appear enigmatic, its part_of relationship to ‘skeletal muscle’ part_of ‘tongue’, makes its homology to EHDAA:9140 ‘intrinsic muscle’ part_of ‘skeletal muscle’ part_of ‘tongue’ clear. Conversely, EMAPA:16370 ‘cardiovascular system’ part_of ‘extraembryonic component’, is not homologous to EHDAA:394 ‘cardiovascular system’, part_of ‘organ system’ part_of ‘embryo’ (Table 2). (iii) The 2962 propositions evaluated represents much less than the 8 202 675 possible pairs of terms between these two ontologies (2327 × 3525; Table 1). The validation rate of 66% shows that these were mostly propositions worth considering, and that the time spent was indeed due to the size of the ontologies, not to a default in the algorithm. Results also show that manual expertise is necessary, since even in the high scoring propositions some are invalid (Table 2). The example of ‘cardiovascular system’ (EMAPA:16370/EHDAA:394) given above appears at iteration 416, with a score improved by shared subcomponents (‘venous system’ and ‘arterial system’). Overall, 27% of invalidations are pairs of terms with identical names. Interestingly, Homolonto manages to give these misleading homonyms low priority: homonyms within the first 1000 iterations have a 99% chance of being homologs, whereas homonyms within the last 1000 iterations only have a 19% chance of being homologs. Thus, 93% of invalidated homonyms appear after iteration 1400.

It is also of interest to consider the capacity of Homolonto to recover homologous terms which are not described by the same name, in a case such as human/mouse where synonyms are not available. Of the 1959 validated homologs, 17% do not have identical names. Many of these share partial homonymy, as between EMAPA:17865 ‘bulbo-ventricular region’ and EHDAA:766 ‘bulbo-ventricular groove’. Such propositions will be recovered by the combination of word matching and propagation of other validated homology relationships (i.e. both are part_of ‘heart’). Structural matching is also able to recover cases with no word matching, as in EMAPA:16211 ‘cardiac muscle’/EHDAA:430 ‘myocardium’. In this case, both terms are part_of ‘early primitive heart tube’. In both ontologies, the latter term has two other children, which are homonyms and homologs: ‘endocardial tube’ and ‘cardiac jelly’. When the homonymous terms have been validated, ‘cardiac muscle’ and ‘myocardium’ remain the only pair of children of ‘early primitive heart tube’, which permits their pairing as a reasonable proposition, following Equation 5b. Similarly, XAO:0003033 ‘nostril’ and ZFA:0000550 ‘naris’ are correctly identified as homologs, since both have is_a relations to ‘surface structure’, and part_of ‘head’.

7 DISCUSSION

The main feature of Homolonto is its efficiency in identifying and ranking valid pairs of terms. Although most homologies concern terms with the same name, the algorithm is successful both in generating relevant propositions for terms with different names, and in ranking poorly terms with the same name which are not homologs. The algorithm has been shown to perform well in proposing valid pairs of homologous terms for two quite different cases. Zebrafish and Xenopus have divergent anatomies, from the two major branches of vertebrates (ray-finned fishes and tetrapodes), but are described by ontologies which follow consistent guidelines (Haendel et al., 2008). The Xenopus ontology is also relatively small. Conversely, human and mouse have very similar anatomies (both are mammals), but are described by large ontologies with little structured information. Despite these differences, the results of Homolonto are consistent, proposing almost exclusively valid pairs in a first series of iterations covering approximately half of the smaller ontology: 250 iterations for Xenopus/zebrafish, 1400 iterations for human/mouse.

The size of some biological ontologies makes the user interface important. The GUI of Homolonto provides rapid access to information about the terms considered, and includes keyboard shortcuts. The combination of an algorithm which proposes relevant pairs of terms, and of this GUI, allows the alignment of large ontologies of anatomy in reasonable time (i.e. weeks).

As all propositions have to be manually validated, the expertise of the curator is important to consider. In our experience, most propositions between closely related species represent ‘text-book’ knowledge, that do not require the curator to be an anatomy expert (although she/he needs to be a biologist). On the other hand, when dealing with complex structures (e.g. substructures of the brain) or distant species (e.g. alignment of insect and vertebrate anatomies), such an expertise might be needed.

Future development of Homolonto should include more relationships than simple homology. For example, homoplasy (analogy in the common sense of the word) may be relevant in cases of functional equivalence, such as the vertebrate and insect eyes. Also, it would be of interest to model explicitly serial homology, to improve the management of e.g. somites.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Aurélie Comte, Anne Niknejad and Emilie Person for manual verification of homology groups within Bgee.

Funding: Etat de Vaud, Swiss National Science Foundation (116798); the Décrypthon program of Association Française contre les Myopathies; the European program Crescendo.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Aitken S. Formalizing concepts of species, sex and developmental stage in anatomical ontologies. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2773–2779. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldock RA, et al. EMAP and EMAGE: a framework for understanding spatially organized data. Neuroinformatics. 2003;1:309–325. doi: 10.1385/NI:1:4:309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian F, et al. Bgee: Integrating and Comparing Heterogeneous Transcriptome Data Among Species. Evry, France: Springer; 2008. pp. 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Bowes JB, et al. Xenbase: a Xenopus biology and genomics resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D761–D767. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day-Richter J, et al. OBO-Edit - an ontology editor for biologists. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2198–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euzenat J, Shvaiko P. Ontology Matching. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazvinian A, et al. Creating Mappings For Ontologies in Biomedicine: Simple Methods Work. San Francisco, CA: AMIA; 2009. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumbling G, et al. FlyBase: anatomical data, images and queries. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D484–D488. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haendel MA, et al. CARO—the common anatomy reference ontology. In: Burger A, Davidson D, Baldock R, editors. Anatomy Ontologies for Bioinformatics: Principles and Practice. London, UK: Springer; 2008. pp. 327–349. [Google Scholar]

- Hall B. Homology: The Hierarchical Basis of Comparative Biology. San Diego, USA: Academic Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hossfeld U, Olsson L. The history of the homology concept and the “Phylogenetisches Symposium”. Theory Biosci. 2005;124:243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.thbio.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter A, et al. An ontology of human developmental anatomy. J. Anat. 2003;203:347–355. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2003.00224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelso J, et al. eVOC: a controlled vocabulary for unifying gene expression data. Genome Res. 2003;13:1222–1230. doi: 10.1101/gr.985203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger A, et al. Simplified ontologies allowing comparison of developmental mammalian gene expression. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R229. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-10-r229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambrix P, He T. Ontology alignment and merging. In: Burger A, Davidson D, Baldock R, editors. Anatomy Ontologies for Bioinformatics: Principles and Practice. London, UK: Springer; 2008. pp. 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Lussier YA, Li J. Terminological mapping for high throughput comparative biology of phenotypes. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2004:202–213. doi: 10.1142/9789812704856_0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux J, Robinson-Rechavi M. An ontology to clarify homology-related concepts. Trends in Genetics. 2010;26:99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shubin N, et al. Deep homology and the origins of evolutionary novelty. Nature. 2009;457:818–823. doi: 10.1038/nature07891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shvaiko P, Euzenat J. A survery of schema-based matching approaches. J. Data Seman. 2005;IV:146–171. [Google Scholar]

- Smith B, et al. Relations in biomedical ontologies. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R46. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-5-r46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B, et al. The OBO Foundry: coordinated evolution of ontologies to support biomedical data integration. Nat. Biotech. 2007;25:1251–1255. doi: 10.1038/nbt1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague J, et al. The Zebrafish Information Network: the zebrafish model organism database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D581–D585. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington NL, et al. Linking human diseases to animal models using ontology-based phenotype annotation. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.