Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) belongs to the most frequent tumors worldwide with an incidence still rising. Patients with cirrhosis are at the highest risk for cancerogenesis and are candidates for surveillance, and here, as well as for the choice of potential forms of treatment, identification of suitable parameters for estimating the prognosis is of high clinical importance. The aim of this study was to describe the etiology of underlying liver disease and to identify predictors of survival in a large single center cohort of HCC patients in Southern Germany. Clinicopathologi-cal characteristics and survival rates of 458 patients (83.6% male; mean age: 62.5±11.2 years) consecutively admitted to a University Hospital between 1994 and 2008 were retrospectively analyzed. The results indicate that chronic alcohol abuse was the most common risk factor (57.2%), followed by infection with hepatitis B and C viruses (HBV: 10.9% and HCV: 20.5%). Overall median survival was 19.0 months, and higher OKUDA, CHILD and CLIP scores correlated negatively with prognosis. Of these, only the CLIP Score was an independent predictor in multivariate analysis. We conclude that chronic alcohol abuse is frequently associated with HCC in low hepatitis virus endemic areas, such as Germany. Our study suggests the CLIP score as a valuable prognostic marker for patients’ survival, particularly of patients with alcohol related HCC.

Keywords: CLIP score, hepatocellular carcinoma, HCC, epidemiology, survival

Introduction

Despite new therapies and attempts at early detection of primary liver cancer, the by far most common form, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), remains a disease with a poor prognosis and a yearly fatality ratio close to 1.0 [1]. The mortality rates are accordingly high in relation to incidence - worldwide HCC has the 5th highest cancer incidence but the 3rd highest cancer mortality [2]. In Europe, which is considered as a low-endemic area, HCC was estimated to be the 14th most common cancer in 2006 but had the 7th highest mortality [1].

The regional differences in prevalence mostly reflect the different incidence of chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) [3]. In most of the Asia-Pacific regions as well as in Africa endemic HBV is the most important etiological factor, with the notable exception Japan, where HCV is by far the most common risk factor. Within Europe there are also differences with regard to etiology. In Southern Europe viral etiology accounts for as much as 76% of HCC cases [4] while in Central and Northern Europe HBV or/and HCV infections are present in only about half of patients [5-7]. Notably, etiology of HCC is not static as the rate of HCV is increasing in Europe [8], HBV prevalence is decreasing in Asia [1], and emerging etiological factors such as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) will play a greater role in the future. This underlines the need for frequent reassessment of HCC risk factors as one central key to improve screening and prevention programs.

The aim of the present study was to describe the etiology, clinicopathological characteristics and survival rates of HCC, and to identify predictors of survival, respectively, in a single-centre cohort of 458 patients in Southern Germany.

Patients and methods

Demographic and clinical patient data

The medical records of 458 HCC patients who had been consecutively admitted to the University Hospital Regensburg between 1994 and 2008 were analyzed retrospectively.

Diagnosis of HCC was based on histology in 396 (86.5%) of cases, and in 2 cases (0.4%) on the cytology of ascites, respectively. In the remaining 60 cases (13.1%) the diagnosis was defined by a combination of increased AFP and imaging of a liver lesion consistent with HCC (ultrasound confirmed by either computer tomography [CT] or magnet resonance imaging [MRI]).

A series of demographic and clinical data were collected including etiology of liver cirrhosis. Alcohol abuse as an etiological factor for HCC was defined as chronic alcohol consumption of > 60 g/day for more than 10 years or when a history of alcohol abuse was noted in the patient's records. HBV and HCV status were collected from the medical records or when information on these was incomplete, from the primary physicians of the patients. Patients with uncertain HBV/HCV status (n=57) were excluded from analyses involving etiological factors.

The diagnosis of cirrhosis was based either on histology (n=283) or on unequivocal clinical signs (ascites, typical sonographic appearance suggestive of cirrhosis, hepatic encephalopathy, esophageal varices and/or other clinical signs of portal hypertension; n=64). In 229 of these 347 cirrhotic patients sufficient data were available to calculate Child scores or Child score was documented in the records, respectively.

Serum parameters

The following serum laboratory parameters were extracted from the medical records of the patients at the time of diagnosis and were considered only if no invasive (e.g. liver biopsy) or medical procedures (e.g. dialysis, fresh frozen plasma (FFP) transfusion) with a possible confounding effect had been performed shortly before blood drawing: a-fetoprotein (AFP), aspar-tate aminotransferase (AST), alanine ami-notransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyl-transferase (y-GT), albumin, prothrombin time (PT) according to Quick, bilirubin, lactate-dehydrogenase (LDH), choline esterase (CHE) and platelet count.

Tumor characteristics and tumor staging

Morphological characteristics of the tumor were recorded based on reports from pathological or radiological examinations including diameter of the largest tumor lesion, number of liver segments involved (according to Couinaud), portal vein thrombosis, and tumor appearance (solitary, bifocal or multifocaI/diffuse).

The T category was noted separately, either defined histomorphologically in cases with hepatic resection, or transplantation (pT), or - if possible - clinically, as defined by clinical and radiological information at the time of diagnosis (cT). The presence of regional lymph node metastases was noted being positive when enlarged lymphatic nodes were detected by CT/MRI. Further, distant metastases (M), peritoneal carcinosis and Edmondson-Steiner grading (G) were documented [9].

Stage of HCC was evaluated according to the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program CLIP [10] and OKLJDA [11] scoring systems. In brief, the CLIP Score takes into account Child Pugh Class, tumor morphology, AFP serum level and the presence of portal vein thrombosis to calculate a score of 0-6 (0: early stage, 1-3: intermediate stage, and 4-6: advanced stage). The OKLJDA staging system uses tumor size, ascites, albumin and bilirubin levels to stratify HCC patients in 3 groups: 0KUDA Stages I, II and III. 0KUDA Stages and CLIP Scores were either taken from the records or calculated if sufficient data were available.

Survival data

Survival data were acquired from clinical records or by contacting the patient's primary physician by telephone call or fax. For 308 cases survival data were cross-checked with information from the death register of the registration office. Thus, a complete follow-up was possible in 364 cases. Mean time of follow up was 18.7 (0-133) months.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS 15.0. Numerical data are presented as means ± standard deviations and compared by one-way analysis of variance (with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons) unless noted otherwise. Categorical data are presented as counts and percentages and assessed by Chi-Square tests. Patient survival was calculated and plots were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Univariate analysis of prognostic variables was performed by the log-rank test and multivariate analysis by a Cox proportional hazards model. Reported p values are two-sided and are considered significant if p <0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics were evaluated for the entire cohort (Table 1). The study population included 458 patients, 383 (83.6%) of which were men and 75 (16.4%) women. The mean age of all patients was 62.5 ± 11.2 years.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at the time of diagnosis of HCC

| Patient characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Males | 83.6 % |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 62.5 ± 11.2 years |

| Liver cirrhosis1 | |

| (based on histology) | 85.2 % |

| Child-Pugh class2 | |

| A | 40.2 % |

| B | 45.4 % |

| C | 12.7 % |

In 283 cases enough tissue for histological analysis of cirrhosis was available.

In 229 HCC patients with histologically or clinically defined cirrhosis enough data were available to calculate Child scores. Age and gender data were determined for the whole cohort (n=458). SD = standard deviation.

Enough non-tumorous liver tissue for histological assessment of liver cirrhosis was available from 283 HCC-patients. Here, histological analysis revealed the presence of liver cirrhosis in 241 (85.2%) of cases.

In addition to the 241 patients with histologically defined cirrhosis 64 patients revealed unequivocal clinical signs of cirrhosis. Sufficient data for Child-Pugh score determination were available of 229 HCC patients with either clinical or histological diagnosis, and here, 92 (40.2%) HCC patients had Child-Pugh class A, 104 (45.4%) had class B and only 33 (12.7%) fell into class C.

Etiology of HCC

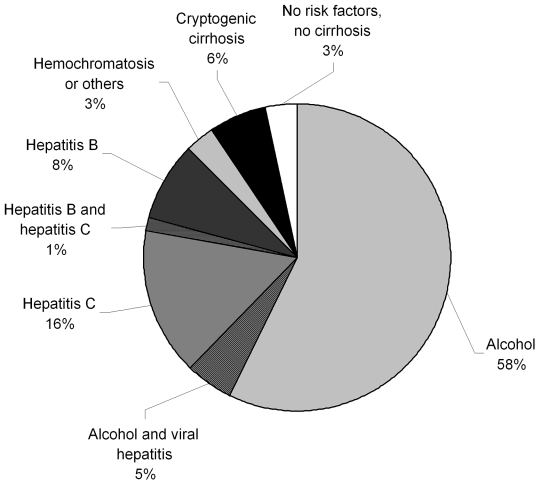

The risk factors for HCC are summarized in Figure 1. The by far most common etiological factor was chronic alcohol abuse, which was identified as sole risk factor in 214 (57.2%) patients. Further, alcohol abuse was an additional risk factor in 19 (5.0%) patients with concomitant hepatitis C (n=14 (3.7%), or hepatitis B (n=5 (1.3%) infection.

Figure 1.

Etiology of underlying liver disease of HCC patients. Data of 374 patients are depicted. Patients with incomplete information on risk factors (n=84) were excluded from analysis.

The second most frequent risk factor was HCV infection, which was identified as a sole risk factor in 58 (15.5%) patients and as concomitant factor in another 19 (5.0%) cases (in 14 (3.7%) cases together with alcohol and in 5 (1.3%) with HBV). The third most common etiological factor was HBV infection, which was exclusively observed in 31 (8.3%) patients and as a concomitant factor in other 10 (2.6%) cases. Overall, HCV was found in 77 (20.5%) and HBV in 41 (10.9%) patients, and thus, in 113 (30.2%) patients HCC could be attributed (solely or in part) to viral etiology. In 7 cases (1.5%) HCC could be attributed to hemochromatosis. Cryptogenic cirrhosis accounted for 23 cases (6.2%), while in 12 cases (3.2%) no underlying liver disease was found.

Analysis of serum parameters

AST, ALT, Y-GT, albumin, bilirubin, LDH, choline esterase serum levels as well as prothrombin time (PT) according to Quick and platelet count at the time of HCC diagnosis are summarized in Table 2. None of these parameters varied significantly between patients with chronic alcohol abuse and other HCC risk factors (data not shown).

Table 2.

Serum parameters at the time of diagnosis of HCC

| Serum parameter (normal range) | All patients | Males | Females |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspartate aminotransferase (M: <50 U/l, F: <35 U/l) | 66.5 ± 81.1 | 68.1 ± 80.4 | 56.7 ± 85.6 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (M: <50 U/l, F: <35 U/l) | 53.6 ± 56.5 | 54.8 ± 57.4 | 46.6 ± 51.4 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase (M: <55 U/l, F: <35 U/l) | 191.9 ± 189.6 | 192.8 ± 184.8 | 179.4 ± 219.7 |

| Albumin (37-53 mg/dl) | 37.2 ± 8.1 | 37.1 ± 8.1 | 37.7 ± 7.7 |

| Prothrombin time acc. to Quick (>70 %) | 83.4 ± 18.5 | 83.5 ± 18.6 | 83.3 ± 18.3 |

| Bilirubin (< 1.0 mg/dl) | 2.7 ± 4.5 | 2.8 ± 4.6 | 2.2 ± 3.3 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (100-247 U/l) | 270.0 ± 153.5 | 257.2 ± 118.8 | 353.1 ± 281.8 |

| Cholinesterase (5.3-12.9 kU/l) | 3.10 ± 1.85 | 3.14 ± 1.88 | 2.84 ± 1.64 |

| Platelet count (130-400 103/μl) | 222 ± 135 | 217 ± 126 | 261 ± 189 |

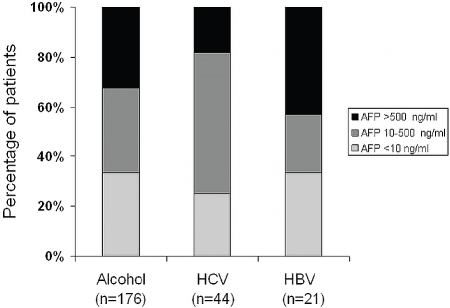

AFP values at the time of diagnosis were available of 352 HCC-patients. In approximately one third of these patients (n=126; 35.8%) AFP serum levels were within the normal range (<10 ng/ml) irrespective of the genesis of liver disease. In nearly another third (n=106; 30.1%) AFP levels were higher than 500 ng/ml, e.g. in a range that may be considered as “diagnostic” for HCC [12]. The rest (n=120; 34.1 %) revealed AFP levels between 10 and 500 ng/ml.

Distribution of AFP serum levels according to the etiology of underlying liver disease is depicted in Figure 2. This analysis focused on the major etiological factors: alcohol abuse and HBV or HCV infection, and thus, 241 patients with documented AFP levels. Interestingly, the proportion of patients with HBV related HCC and AFP levels above 500 ng/ml (42.9%) was significantly higher than in the groups of HCV- or alcohol-related HCC (18.2% and 32.4 %, respectively; p<0.01).

Figure 2.

AFP serum levels at the time of diagnosis according to major etiologies. Data reflect a total of 241 patients who had (1) documented AFP levels at the time of diagnosis and (2) only one of the three major etiological factors: alcohol abuse or chronic hepatitis B (HBV) or hepatitis C (HCV) as a solitary risk factor. AFP levels are classified as normal (<10 ng/ml), moderately elevated (10-500 ng/ml) or considerably elevated (>500 ng/ml).

Tumor characteristics

Characteristics of primary hepatoceiiuiar tumors are summarized in Table 3. Most tumors presented as solitary lesions (53.4%) and the majority of tumors were restricted to one or two liver segments (69.0%). Only 32 (9.8%) of tumors were smaller than 20 mm, while the majority (n=127, 39.3%) were determined to be between 21 and 50 mm in size at the time of diagnosis. At the time of HCC diagnosis 59 (12.9%) patients revealed radiological signs of lymph node involvement, and 32 (7.0%) patients had distant metastases (the most common of which were lung (50%) and bone (23%) metastases, data not shown). Radiological evidence of portal vein thrombosis was found in 51 (16.6%) of patients. Most patients fell into OKUDA Stage II (173, 54.6%), while 115 (36.3%) were classified as OKUDA Stage I, and only 29 (9.1%) as OKUDA Stage III. Interestingly, the large majority of patients had comparatively low CLIP Scores 0-2 (overall 82.7%).

Table 3.

Tumor characteristics

| Tumor characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of tumor nodules | |

| solitary | 223 (53.4%) |

| bifocal | 34 (8.1%) |

| multifocal or diffuse | 161 (38.5%) |

| nd | 60 |

| Number of tumorous | |

| liver segments (Couinaud) | |

| 1 | 81 (36.0%) |

| 2 | 75 (33.3%) |

| 3 | 31 (13.8%) |

| 4 | 15 (6.7%) |

| >4 | 23 (10.2%) |

| nd | 233 |

| Tumor size (mm) | |

| ≤20 | 32 (9.8%) |

| 21-50 | 127 (39.3%) |

| 51-100 | 105 (32.4%) |

| >100 | 60 (18.5%) |

| nd | 134 |

| pT Stadium; cT Stadium | |

| pT1; cT1 | 41(22.9%); 41 (13.4%) |

| pT2; cT2 | 59(33.0%); 59 (19.3%) |

| pT3; cT3 | 66(36.9%); 100 (32.8%) |

| pT4; cT4 | 13(7.2%); 105 (34.5%) |

| nd | 279; 153 |

| N (lymph node metastases) | |

| N0 | 399 (87.1%) |

| N+ | 59(12.9%) |

| nd | |

| M (distant metastases) | |

| M0 | 426 (93.0%) |

| M1 | 32(7.0%) |

| nd | |

| Peritoneal carcinosis | |

| yes | 15(3.3%) |

| no | 443 (96.6%) |

| nd | |

| Pathological Grading | |

| G1 | 76(25.1%) |

| G2 | 190 (62.7%) |

| G3 | 37(12.2%) |

| nd | 155 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | |

| yes | 51(16.6%) |

| no | 257 (83.4%) |

| nd | 150 |

| OKUDA Stage | |

| I | 115 (36.3%) |

| II | 173 (54.6%) |

| III | 29 (9.1%) |

| nd | 141 |

| CLIP Score | |

| 0 | 61 (24.6%) |

| 1 | 79 (31.9%) |

| 2 | 65 (26.2%) |

| 3 | 37 (14.9%) |

| 4-6 | 6 (2.4%) |

| nd | 210 |

nd: not determined/no data available.

Treatment modalities

Table 4 summarizes the treatment modalities of the HCC patients of our cohort. In 142 patients primary therapy was hepatic resection, and in 7 (1.5%) of these patients resection was followed by a liver transplantation, while in 11 (2.3%) of cases a second resection was necessary after HCC recurrence. In 36 patients (7.9%) primary liver transplantation was performed. Overall, 178 patients (38.9%) received surgical treatment with curative intention. From the remaining patients, 93 (20.3%) received local ablative therapy (transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) or radio-frequency ablation (RFA)), while in other 93 (20.3%) of cases no specific therapy was applied. Chemotherapy alone (mostly with tamoxifen, but also with octreotide and soraf-enib) was chosen in 50 (10.9%) cases, while in 20 (4.4%) patients local ablative therapy was followed by chemotherapy. 9 patients (2.0%), who rejected chemo-/or local ablative therapy, participated in a multicenter study and received a thymus gland extract (thymophysin), and 8 patients (1.7%) were treated with a combination of various local ablative therapies. Percutaneous ethanol injection alone was performed in 7 (1.5%) cases. Overall, 187 patients (40.8%) received specific palliative therapy and 93 patients (20.3%) only best supportive care.

Table 4.

Treatment modalities of 458 HCC patients

| Therapy | N (%) |

|---|---|

| resection | 124 (27.1%) |

| best supportive care (no specific therapy) | 93 (20.3%) |

| local ablative therapy (TACE, RFA) | 93 (20.3%) |

| chemotherapy only | 50 (10.9%) |

| liver transplantation | 36 (7.9%) |

| combination of chemotherapy and at least one ablative therapy | 20 (4.4%) |

| multiple resections | 11 (2.4%) |

| therapy with thymophysine | 9 (2.0%) |

| combination of various ablative therapies | 8 (1.7%) |

| percutaneous ethanol injection only | 7 (1.5%) |

| resection followed by liver transplantation | 7 (1.5%) |

Survival

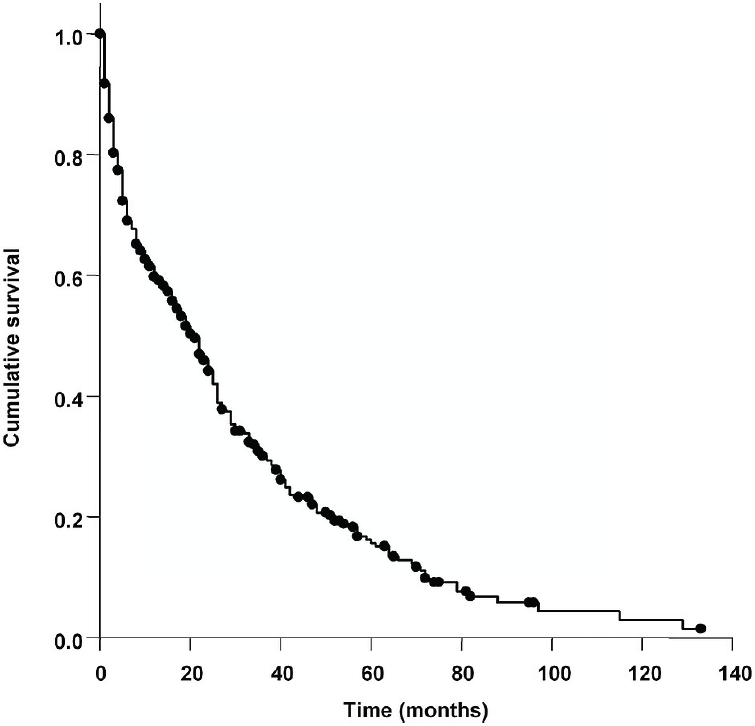

Overall mean follow-up was 18.7 months. At the time of analysis a total of 314 (68.6%) patients had died, 50 (10.9%) were still living and no up-to-date follow-up information was available in 94 (20.5%) cases. Overall median survival was 19.0 months (95% Cl: 15.3-22.7) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve of HCC patients. Data reflect 458 consecutive patients with HCC, both treated and untreated. Median survival was 19 months (95% Cl: 15.3-22.7).

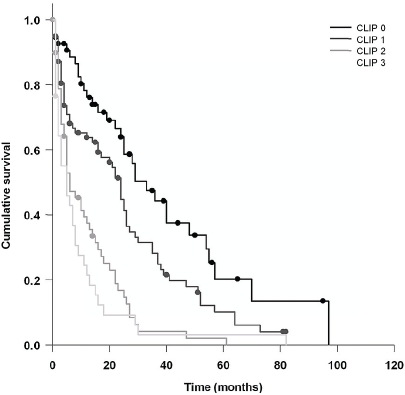

The following 12 clinicopathological and laboratory characteristics were associated with a significant reduction of survival on univariate analysis (Table 5): age>62 years, ascites on ultrasound at the time of diagnosis, lymph node involvement, distant metastases, histolopa-thological grading, portal vein thrombosis, multi-focal lesions, larger tumor size, higher AFP levels, bilirubin > 2.0 mg/dl, albumin <35 mg/dl, and prothrombin time (PT) according to Quick < 70%. Further, higher OKUDA and Child stages correlated negatively with prognosis, and an even stronger negative correlation was observed between the CLIP score and survival (Figure 4). Thus, patients with CLIP scores 0, 1, 2 and 3 had median survival rates of 29, 24, 8 and 3 months, respectively.

Table 5.

Univariate analysis of prognostic factors for survival of HCC patients

| Mean survival estimate (months) | Median survival estimate (months) | 95 % CI for median | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| male | 27.7 | 18 | 13.8-22.2 | 0.482 |

| female | 31.8 | 22 | 14.1-29.9 | |

| Age | ||||

| >62 years | 24.9 | 16 | 11.4-20.6 | 0.031 |

| <62 years | 33.5 | 24 | 19.5-28.5 | |

| Etiology | ||||

| alcohol | 27.5 | 18 | 12.2-23.8 | 0.722 |

| HCV | 32.0 | 25 | 7.4-42.6 | |

| HBV | 24.5 | 22 | 11.9-32.1 | |

| Ascites on ultrasound | ||||

| yes | 15.4 | 4 | 2.6-5.4 | <0.001 |

| no | 31.0 | 22 | 16.7-27.3 | |

| Cirrhosis | ||||

| yes | 29.0 | 22 | 18.7-25.3 | 0.110 |

| no | 37.1 | 26 | 18.6-33.4 | |

| Lymph node involvement | ||||

| N0 | 30.1 | 22 | 18.2-25.8 | 0.003 |

| N+ | 17.5 | 8 | 3.4-12.6 | |

| Distant metastases | ||||

| M0 | 29.7 | 20 | 16.0-24.0 | 0.001 |

| M1 | 13.9 | 3 | 1.1-4.9 | |

| Tumor Grading | ||||

| G1 | 39.3 | 30 | 19.5-40.9 | 0.045 |

| G2 | 30.2 | 21 | 16.5-25.5 | |

| G3 | 20.9 | 10 | 0.9-19.1 | |

| Tumor size | ||||

| <30 mm | 40.8 | 40 | 17.1-62.9 | 0.001 |

| >30 mm | 27.1 | 18 | 14.1-21.9 | |

| Number of lesions | ||||

| unifocal | 37.1 | 30 | 24.6-35.4 | <0.001 |

| multifocal | 19.4 | 8 | 1.8-14.2 | |

| Portal vein thrombosis | ||||

| yes | 10.2 | 5 | 3.1-6.9 | <0.001 |

| no | 28.9 | 20 | 15.8-24.2 | |

| Child-Pugh Class | ||||

| A | 24.7 | 14 | 8.9-19.1 | <0.001 |

| B | 19.7 | 7 | 0.0-15.4 | |

| C | 4.7 | 1 | 0.0-3.1 | |

| OKUDA Stage | ||||

| Stage I | 28.2 | 18 | 10.8-25.2 | <0.001 |

| Stage II | 22.7 | 11 | 5.2-16.8 | |

| Stage III | 10.6 | 2 | 0.6-3.4 | |

| CLIP Score | ||||

| 0 | 38.2 | 29 | 19.8-41.0 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 25.2 | 24 | 17.0-28.2 | |

| 2 | 12.3 | 8 | 2.0-14.0 | |

| 3 | 8.9 | 3 | 0.7-5.3 | |

| 4 | 0.8 | 0 | ** | |

| 5 | 0.5 | 0 | ** | |

| AFP | ||||

| <10 ng/ml | 33.5 | 26 | 19.6-32.4 | <0.001 |

| 10-500 ng/ml | 22.6 | 17 | 10.8-23.2 | |

| >500 ng/ml | 17.5 | 5 | 3.6-6.4 | |

| Bilirubin | ||||

| <2 mg/dl | 26.8 | 16 | 11.0-21.0 | <0.001 |

| >2 mg/dl | 14.0 | 3 | 1.2-4.8 | |

| Albumin | ||||

| >35 mg/dl | 23.8 | 11 | 5.6-16.4 | 0.019 |

| <35 mg/dl | 16.5 | 4 | 2.5-5.5 | |

| PT (acc. to Quick) | ||||

| <70 % | 15.2 | 4 | 1.1-6.9 | 0.014 |

| >70% | 23.0 | 12 | 7.6-16.4 |

by Mantel log-rank test. Bold-face p values indicate significant predictors

not calculated because of too small number of cases (n=4 and 2 respectively) reaching the terminal event

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve of patients stratified according to CLIP score. Comparison of patients with CLIP scores 0-3 provided validation of the excellent prognostic power of the CLIP score (as best predictor) in our study population. This analysis was based on total of 242 patients where complete data was available to calculate the CLIP scores 0-3.

On multivariate analysis (Table 6) six variables remained independent predictors of (shorter) survival: age > 62 years, poorer histolopa-thological grading, multifocal tumor, portal vein thrombosis, higher AFP and bilirubin serum levels. When the OKUDA, CHILD and CLIP scores were entered in a multivariate model, only the CLIP score remained an independent predictor of survival (model not shown)

Table 6.

Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for survival of HCC patients

| Variables included | Relative risk (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Age > 62 years | 2.03 (1.12-3.69) | 0.020 |

| Ascites on ultrasound | 0.77 (0.46-1.30) | 0.326 |

| Lymph node involvement (N+) | 0.78 (0.33-1.87) | 0.580 |

| Distant metastases (M1) | 1.38 (0.37-5.12) | 0.630 |

| Tumor Grading (ref. category G1) | ||

| G2 | 1.82 (0.94-3.53) | 0.064 |

| G3 | 3.74 (1.52-9.22) | 0.007 |

| Tumor size > 30 mm | 1.54 (0.65-3.67) | 0.327 |

| Number of lesions (ref. category solitary) | ||

| bifocal | 2.10 (0.81-5.40) | 0.127 |

| multifocal | 2.36 (1.29-4.36) | 0.006 |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 2.91 (1.28-6.62) | 0.011 |

| AFP (ref. category <10 ng/ml) | ||

| 10-500 ng/ml | 1.32 (0.71-2.42) | 0.379 |

| >500 ng/ml | 2.22 (1.12-4.40) | 0.022 |

| Bilirubin > 2 mg/l | 3.32 (1.56-7.10) | 0.002 |

| Albumin < 35 mg/dl | 1.67 (0.78-2.94) | 0.172 |

| PT acc. to Quick < 70 % | 0.94 (0.42-2.12) | 0.890 |

To identify independent predictors of survival we included all significant predictors on univariate analysis in a Cox proportional hazards model. The contribution of variables was assessed in a backward-stepwise fashion after the maximum-likelihood method. The overall significance of the model was < 0.001.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the characteristics of a large series of HCC patients in Southern Germany. We studied a total of consecutive 458 patients consecutively administered to a single University Hospital Center, and herewith, this study represents one of the most comprehensive investigations of HCC patients in Europe.

Notably, in the majority of cases chronic alcohol abuse was identified as underlying cause of liver disease and risk factor for HCC, respectively. This finding is in contrast to most studies in other European countries, where viral hepatitis has been identified as major risk factor. Thus a large study from Italy reported that 87.5 % of HCC patients had positive serological markers for HBV or HCV infection [13], and also in Austria [7] and Belgium [5] viral etiology was predominant in more than 50% of cases. In a Turkish study 71 % of HCC patients revealed viral hepatitis [14], and still, in a study from Northern German HCC was associated with HBV or HCV in more than 50% of cases [15]. Only in Portugal viral infection was the second most frequent HCC risk factor in 41% of HCC cases, while chronic alcohol abuse was the most important cause of underlying liver disease [16], similarly to our study. Together, these data point to strong differences regarding viral hepatitis on the one hand and chronic alcohol abuse on the other hand as risk factors for HCC. One reason for this variation may be a different prevalence of chronic viral hepatitis. Thus, the prevalence of HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) in the general Germany population was found to be 0.62% [17] while the HBsAg prevalence in Italy is 1.0% [18]. Similarly, anti-HCV prevalence in Germany (0.63%) is approximately 4-fold lower than in Italy (2.6%) [18,19].

Further, one may speculate whether different frequency or extent of chronic alcohol abuse in the general population account for the relatively high percentage of alcohol-related HCC cases in our study. However, a comprehensive study [20] found that in general, mean ethanol consumption is even higher in North Germany than in South Germany although the percentage of alcohol-related HCC in our study was higher than in one from North Germany [15]. On the other hand one has to consider that even within Bavaria, where most of the patients of our study lived, there is a strong heterogeneity among patients coming from urban versus more rural regions. To the latter belongs the region near to the previous “iron curtain” at the border to the Czech Republic, known to have higher rates of behavioral health risk factors including alcohol consumption [21].

In contrast to the cause of underlying liver disease, the extent of liver damage, e.g. the high rate of cirrhosis (85.2%), in our study is very similar to other European studies [7,15,16] and reinforces that in Europe HCC develop predominantly in cirrhotic livers. In almost all (97.5%) patients with HCV chronic infection HCC was found in a cirrhotic liver while only approximately two-third (73.3%) of patients with HBV related HCC revealed liver cirrhosis (data not shown). These numbers are similar as in other European studies [15] and are in accordance, respectively, with studies in China, that report both the highest proportion of HBV related HCCs [1] and the lowest proportion of HCC in cirrhosis [22]. We further found, that patients with HBV-related HCC were significantly younger than patients with other etiologies (55.8 ± 15.9 vs. 62.6 ± 8.9 (alcohol), 64.0 ± 9.9 (HCV), p<0.01). This finding parallels previous studies [23,24] and possibly reflects an early time of infection, and herewith, longer duration of liver disease as compared to patients with alcohol-associated HCC and later onset of chronic alcohol abuse.

The overall median survival rate in our study was 19 months (95% Cl: 15.3-22.7). In general, there is considerable variation in survival rates reported in different studies. Thus, consecutive clinical series in low-endemic regions as Austria [7] or the United States [25] present a range of 2-10 months, while recent studies from Turkey [14], Italy [10] and Portugal [16] report between 17 and 24 month survival rates. One could speculate, that more recent studies reveal better survival due to improved treatment and/or diagnosis at earlier stage. However, there are also most recent studies that report a dismal 3.5 months median survival [26]. Our study spans over a 14 year period (1994-2008), and we did find differences with regards to median survival rates comparing patients diagnosed before the year 2001 (17 months (95% Cl: 9.2-24.8) and thereafter (20 months (95% Cl: 15.8-24.1), respectively. However, this difference did not reach statistical significance further confirming that other factors account for variable survival rates reported. Some of the highest median HCC survival rates are found in selected populations in Italy (25.7 months) where “early-intermediate” tumors have been identified in a HCC prevention program [27], and in Taiwan (26.8 months) in a cohort of patients undergoing hepatic resection [28]. Also in our study approximately one third of patients underwent liver resection or transplantation, respectively, and more than 80% of HCCs have been diagnosed at a relatively earlier stage, e.g. CLIP score 0-2.

In our study no complete survival information was available for 20.5 % of patients. This results from the difficulty of obtaining long-term survival data in retrospective studies in a country with no centralized cancer register. Yet, this is a relatively low share and is unlikely to bias results.

Multivariate analysis identified six independent negative predictors of survival of HCC patients at the time of diagnosis, one of which was age. This has to be noted, since although HCC is a disease occurring in the elderly, and age is commonly not included in prognostic analysis, older HCC patients have significantly worse survival. Poorer histopathological grading was an independent predictor of survival, which indicates that the degree of tumor differentiation also has a unique impact on survival. Interestingly, a multifocal growth pattern rather than tumor size was another independent predictor. Further, portal vein thrombosis, indicative of advanced disease, appeared as independent risk factor with generally no curative treatment options. Although one third of patients revealed AFP levels in the normal range at the time of diagnosis, higher AFP levels remained a significant predictor of survival also on multivariate analysis. This indicates that AFP may be suitable as a prognostic marker but underscores the limited use of AFP as a screening tool. Finally, serum bilirubin was found to be a predictor of HCC survival, while serum albumin and prothrombin time were predictors only on univariate analysis.

Notably, we validated the superior predictive power of the CLIP score over the OKUDA and the Child-Pugh staging system regarding patients’ survival. The CLIP score was developed in a viral-related HCC setting [10], and has been prospectively validated in a cohort of HCC patients with predominantly HCV etiology [29]. To the best of our knowledge our study is the first, which validates the CLIP score in a representative HCC cohort with chronic alcohol abuse as chief etiological factor. This difference in etiology is important, since a large Chinese HCC study [30] revealed that the CLIP score is of poor predictive power in HBV related HCCs, which indicates that there are even differences between HBV and HCV related HCC. Furthermore, it has been shown that the survival rate of viral marker-negative HCC is lower than in HBV or HCV-related HCC cases [31]. This was similar in our study although differences did not reach statistical significance. Thus, for example median survival rates were 18 months for alcohol-related HCC (95% Cl: 12.1-23.8) vs. 25 months (95% Cl: 7.4-42.6) for HCV-related HCC (p=0.722).

In conclusion, our study reveals that chronic alcohol abuse is frequently associated with HCC in a low hepatitis virus endemic area such as Germany. Further, it promotes the CLIP score as a very good prognostic marker for patients’ survival also for patients with alcohol related HCC.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Medical Faculty of the University of Regens-burg(ReForM) to 0. Sand C.H..

References

- 1.Yuen M, Hou J, Chutaputti A. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the Asia pacific region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Autier P, Boniol M, Heanue M, Colombet M, Boyle P. Estimates of the cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2006. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:581–592. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu MC, Yuan J. Environmental factors and risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stroffolini T. Etiological factor of hepatocellular carcinoma in Italy. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2005;51:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Roey G, Fevery J, Van Steenbergen W. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Belgium: clinical and virological characteristics of 154 consecutive cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Widell A, Verbaan H, Wejstal R, Kaczynski J, Kidd-Ljunggren K, Wallerstedt S. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Sweden, its association with viral hepatitis, especially with hepatitis C viral genotypes. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32:147–152. doi: 10.1080/003655400750045240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoniger-Hekele M, Muller C, Kutilek M, Oesterreicher C, Ferenci P, Gangl A. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Central Europe: prognostic features and survival. Gut. 2001;48:103–109. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Velazquez RF, Rodrfguez M, Navascues CA, Linares A, Perez R, Sotorrfos NG, Martfnez I, Rodrigo L. Prospective analysis of risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2003;37:520–527. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.EDMONDSON HA, STEINER PE. Primary carcinoma of the liver: a study of 100 cases among 48,900 necropsies. Cancer. 1954;7:462–503. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195405)7:3<462::aid-cncr2820070308>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) investigators: A new prognostic system for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 435 patients. Hepatology. 1998;28:751–755. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okuda K, Ohtsuki T, Obata H, Tomimatsu M, Okazaki N, Hasegawa H, Nakajima Y, Ohnishi K. Natural history of hepatocellular carcinoma and prognosis in relation to treatment Study of 850 patients. Cancer. 1985;56:918–928. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850815)56:4<918::aid-cncr2820560437>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hellerbrand C, Hartmann A, Richter G, Knoll A, Wiest R, Scholmerich J, Lock G. Hepatocellular carcinoma in southern Germany: epidemiological and clinicopathological characteristics and risk factors. Dig Dis. 2001;19:345–351. doi: 10.1159/000050702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stroffolini T, Andreone P, Andriulli A, Ascione A, Craxi A, Chiaramonte M, Galante D, Manghisi OG, Mazzanti R, Medaglia C, Pilleri G, Rapaccini GL, Simonetti RG, Taliani G, Tosti ME, Villa E, Gasbarrini G. Characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma in Italy. J Hepatol. 1998;29:944–952. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alacacioglu A, Somali I, Simsek I, Astarcioglu I, Ozkan M, Camci C, Alkis N, Karaoglu A, Tarhan O, Unek T, Yilmaz U. Epidemiology and survival of hepatocellular carcinoma in Turkey: outcome of multicenter study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:683–688. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubicka S, Rudolph KL, Hanke M, Tietze MK, Tillmann HL, Trautwein C, Manns M. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Germany: a retrospective epidemiological study from a low-endemic area. Liver. 2000;20:312–318. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2000.020004312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martins A, Cortez-Pinto H, Marques-Vidal P, Men-des N, Silva S, Fatela N, Gloria H, Marinho R, Tavora I, Ramalho F, de Moura MC. Treatment and prognostic factors in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2006;26:680–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.001285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jilg W, Hottentrager B, Weinberger K, Schlottmann K, Frick E, Holstege A, Scholmerich J, Palitzsch KD. Prevalence of markers of hepatitis B in the adult German population. J Med Virol. 2001;63:96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fabris P, Baldo V, Baldovin T, Bellotto E, Rassu M, Trivello R, Tramarin A, Tositti G, Floreani A. Changing epidemiology of HCV and HBV infections in Northern Italy: a survey in the general population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:527–532. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318030e3ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palitzsch KD, Hottentrager B, Schlottmann K, Frick E, Holstege A, Scholmerich J, Jilg W. Prevalence of antibodies against hepatitis C virus in the adult German population. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:1215–1220. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199911000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraus L, Augustin R, Bloomfield K, Reese A. Der Einfluss regionaler Unterschiede im Trinkstil auf riskanten Konsum, exzessives Trinken, Miss-brauch und Abhängigkeit [The influence of regional differences in drinking style on hazardous use, excessive drinking, abuse and dependence] Gesundheitswesen. 2001;63:775–782. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kemptner D, Wildner M, Abu-Omar K, Caselmann WH, Kerscher G, Reitmeir P, Mielck A, Rutten A. Regionale Unterschiede des Gesund-heitsverhaltens in Bayern - Mehrebenenanalyse einer bevölkerungsrepräsentativen Befragung in Verbindung mit sozioökonomischen Strukturdaten [Regional differences in health behaviour in bavaria - a multilevel analysis of a representative population questionnaire in combination with socioeconomic structural data] Gesundheitswesen. 2008;70:28–37. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1022523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Q, Li H, Qin Y, Wang PP, Hao X. Comparison of surgical outcomes for small hepatocellu-lar carcinoma in patients with hepatitis B versus hepatitis C: a Chinese experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1936–1941. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiratori Y, Shiina S, Imamura M, Kato N, Kanai F, Okudaira T, Teratani T, Tohgo G, Toda N, Ohashi M. Characteristic difference of hepato-cellular carcinoma between hepatitis B- and C-viral infection in Japan. Hepatology. 1995;22:1027–1033. doi: 10.1016/0270-9139(95)90605-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rabe C, Pilz T, Klostermann C, Berna M, Schild HH, Sauerbruch T, Caselmann WH. Clinical characteristics and outcome of a cohort of 101 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:208–215. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i2.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stuart KE, Anand AJ, Jenkins RL. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Prognostic features, treatment outcome, and survival. Cancer. 1996;77:2217–2222. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960601)77:11<2217::AID-CNCR6>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.El-Serag HB, Siegel AB, Davila JA, Shaib YH, Cayton-Woody M, McBride R, McGlynn KA. Treatment and outcomes of treating of hepatocellular carcinoma among Medicare recipients in the United States: a population-based study. J Hepatol. 2006;44:158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grieco A, Pompili M, Caminiti G, Miele L, Covino M, Alfei B, Rapaccini GL, Gasbarrini G. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with early-intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing non-surgical therapy: comparison of Okuda, CLIP, and BCLC staging systems in a single Italian centre. Gut. 2005;54:411–418. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.048124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeh C, Chen M, Lee W, Jeng L. Prognostic factors of hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma with cirrhosis: univariate and multi-variate analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2002;81:195–202. doi: 10.1002/jso.10178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP) Investigators: Prospective validation of the CLIP score: a new prognostic system for patients with cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2000;31:840–845. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leung TWT, Tang AMY, Zee B, Lau WY, Lai PBS, Leung KL, Lau JTF, Yu SCH, Johnson PJ. Construction of the Chinese University Prognostic Index for hepatocellular carcinoma and comparison with the TNM staging system, the Okuda staging system, and the Cancer of the Liver Italian Program staging system: a study based on 926 patients Cancer. 2002;94:1760–1769. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toyoda H, Kumada T, Kiriyama S, Sone Y, Tanikawa M, Hisanaga Y, Kanamori A, Yamaguchi A, Isogai M, Kaneoka Y, Washizu J. Characteristics and prognosis of patients in Japan with viral marker-negative hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:459–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05138.x. and performance for long-duration spaceflight. Aviat Space Environ Med 2008; 79: 629-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]