Obesity has been increasing in epidemic proportions in both adults and children in the United States.1,2 Overweightness and obesity are now critical problems, with the prevalence among adults increasing by nearly 50% during the past 2 decades3; currently nearly 70% of adults are classified as being either overweight or obese compared with fewer than 25% 40 years ago.2,3 Moreover, the distribution of body mass index (BMI) in the United States has drastically shifted in a skewed fashion toward higher values, such that the proportion of the population meeting criteria for morbid obesity has increased more markedly than for overweight and mild levels of obesity.1-4 If we fail to stop this ongoing obesity epidemic, we may soon witness an abrupt end to, or even worse a reversal of, the steady increase in life expectancy noted during the past century.2,5

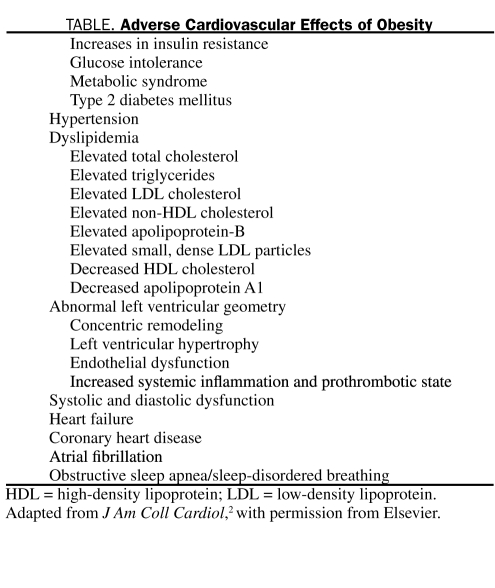

The adverse effects of obesity on overall cardiovascular (CV) health (Table),2 including heart failure (HF), are numerous. In a 14-year follow-up study of 5881 Framingham Heart Study participants, Kenchaiah et al6 found a graded increase in the risk of HF as BMI increased, and for every 1 kg/m2 increase in BMI, the risk of HF increased 5% in men and 7% in women. Clearly, obesity has profound effects on both systolic and diastolic left ventricular function; epidemiological data demonstrate a strong link between obesity, as determined by BMI, and hypertension and coronary heart disease (CHD), 2 powerful risk factors for HF. Despite this evidence, many studies have suggested that obese patients with HF have a better prognosis than leaner patients, which is termed the obesity paradox.2,7 In a meta-analysis of 9 observational HF studies (n=28,209), Oreopoulos et al8 demonstrated that, compared with individuals without elevated BMI, overweight and obese patients with HF had reductions in CV (−19% and −40%, respectively) and all-cause (−16% and −33%, respectively) mortality during a 2.7-year follow-up period. In an analysis of BMI and in-hospital mortality from 108,927 patients with decompensated HF, higher BMI was associated with lower mortality, with a 10% lower mortality (P<.001) for every 5-unit increase in BMI.9

TABLE.

Adverse Cardiovascular Effects of Obesity

Most studies reporting the obesity paradox have used BMI to classify obesity (eg, BMI [calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared]: ≥25 is overweight and ≥30 is obese). Although BMI is the most common method to define overweightness and obesity in both epidemiological studies and major clinical trials, clearly this method does not necessarily reflect true body fatness, and BMI/body fatness may differ considerably among people of different age, race, and sex.2,10-12 As we have discussed previously,2,12 defining obesity by other methods, including waist circumference, waist-hip ratio, and percent body fat (BF), may be more accurate. In fact, researchers at Mayo Clinic have reported that BMI performed suboptimally in predicting obesity as defined by the National Institutes of Health criterion standards (BF >25% in men and >35% in women)13 in cohorts with CHD and in the general population.10,14 The accuracy of BMI in diagnosing obesity appears to be particularly limited in the intermediate BMI ranges, as well as in men and in the elderly. This is of great importance because it is precisely in the intermediate ranges of BMI in which the obesity paradox was first noted (better survival in overweight individuals). Also, historically men comprise the majority of the sample studied in most epidemiological CV studies. Finally, in the elderly in whom most of the outcomes (eg, deaths, myocardial infarction, stroke) occur, BMI has its poorest diagnostic accuracy, probably because the elderly have a relatively low amount of muscle mass. In fact, a BMI cutoff of 30 or greater has good specificity but misses more than half of patients with excess BF.12

See also page 609

The obesity paradox has been blamed in part on the limitations of the BMI assessment for defining overweightness/obesity.2,12,15 In this issue of Mayo Clinic Proceedings, Oreopoulos et al16 report a detailed body composition assessment in 140 patients with chronic HF, including assessment of BF, by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA). Compared with DEXA, use of BMI misclassified BF status in 41% of their cohort. Increased BMI was significantly associated with lower N-terminal pro B-type brain natriuretic peptide and lower exercise capacity; higher BF was associated with lower exercise capacity and increased levels of C-reactive protein. Moreover, when BMI was divided into fat and lean mass components, a higher lean body mass and/or lower fat mass was independently associated with factors that appear to be advantageous in chronic HF. A limitation of the study is that the authors did not assess waist circumference, which is the major component of the metabolic syndrome and is a marker of insulin resistance and at-risk obesity.2,12 Although DEXA is often considered the criterion standard for the assessment of BF, magnetic resonance imaging may better differentiate subcutaneous from visceral fat, which is more proinflammatory. Finally, the authors assessed surrogate markers of CV disease and lacked data for “hard” end points. This becomes important because evidence-based medicine has taught us that the presence of a surrogate marker of CV disease does not always translate into similar data regarding survival.

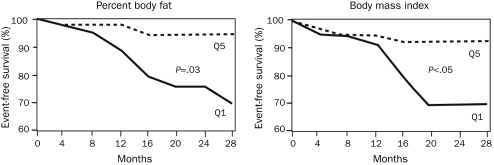

In fact, we have previously shown in a study of 209 patients with advanced chronic systolic HF that both BMI and percent BF (assessed by the sum of the skinfold method as opposed to the more precise DEXA scanning method) are independent predictors of better event-free survival (Figure 1).17 For every 1% increase in BF, clinical events were independently reduced by 13%. Our preliminary data in 875 patients with advanced HF also demonstrate the paradoxical independent prognostic impact of BF by the sum of the skinfold method on all-cause mortality.18

FIGURE 1.

Freedom from cardiovascular death or urgent transplant in patients in quintiles (Q) 1 and 5 for percent body fat (left) and body mass index (right).

From Am J Cardiol 2003,17 with permission from Elsevier.

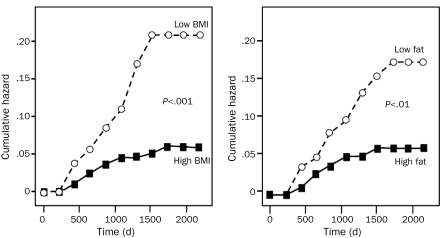

Similar to HF, this obesity paradox has been demonstrated in cohorts with hypertension, peripheral arterial disease, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, and, especially, CHD.2,19 In a recent systematic review of 40 cohort studies involving more than 250,000 patients followed up for 3.8 years, Romero-Corral et al15 reported that overweight and obese patients with CHD have a lower risk of total and CV mortality compared with underweight and normal-weight patients with CHD. However, of importance is the fact that those with morbid obesity had the highest risk of CV mortality. Like our results in HF, we also have demonstrated the obesity paradox with BMI and BF in patients with CHD (Figure 2).20

FIGURE 2.

Actuarial cumulative hazard plot for survival time in 529 patients with coronary heart disease based on baseline body mass index (bMI) status (high, bMI ≥25 kg/m2, vs low, bMI <25 kg/m2) (left) and baseline percent body fat (high fat >25% in men and >35% in women vs low fat) (right).

From Am J Med,20 with permission from Elsevier.

The reasons for the obesity paradox in CV diseases, especially HF, remain unclear.2,7 Because advanced HF is a catabolic state, obese patients with HF may have more metabolic reserve.21-23 Cytokines and neuroendocrine profiles of obese patients with HF may be protective, and adipose tissue produces stable tumor necrosis factor α receptors that could be protective.8 Additionally, overweight and obese patients with HF have lower levels of brain natriuretic peptide.21 High circulating lipoprotein levels in obese patients may bind and detoxify lipopolysaccharides that play a role in stimulating the release of inflammatory cytokines, all of which may serve to protect the obese patient with HF.21,24 In a study of a large non-HF cohort recently published by McAuley et al25 in Mayo Clinic Proceedings, the obesity paradox was noted only in overweight and obese patients with a high level of cardiorespiratory fitness, suggesting that the obesity paradox may be modified by physical wellness or other unmeasured confounding factors that link the presence of chronic disease to outcomes.26 Additionally, the obesity paradox in overweight/obese patients with higher levels of fitness may be due to these patients having a higher amount of lean muscle mass and not necessarily due to having more fat mass.11 Finally, as we have suggested previously,2,20,27 overweight and obese patients with CV diseases, including HF, might not have developed these diseases if weight gain had been prevented. In contrast, leaner patients who develop these same CV diseases and HF may have a different pathophysiologic etiology, including genetic predisposition, that leads to resistance to medical interventions. Although most studies that support the obesity paradox have corrected for baseline conditions, such as tobacco use and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, these studies generally did not account for nonpurposeful weight loss before study entry, which may represent undiagnosed severe underlying diseases.2,28

Why higher BF by the sum of the skinfold method is protective and high BF by DEXA is associated with better HF prognostic markers is puzzling. Clearly, DEXA scanning is more accurate than the simple, inexpensive sum of the skinfold method.20 Furthermore, other inexpensive and easier methods to measure BF, such as bioimpedance, may have a huge selection bias for the study between BF and HF with CV mortality, because bioimpedance is not recommended for patients with implantable pacemakers and defibrillators, which are commonly used in HF (especially in the sickest patients). Despite its limitations in very obese and elderly people, higher BF by the sum of the skinfold method has been shown to be protective in both HF and CHD.17,20 Such data are not yet available for BF assessed by DEXA. However, preliminary data from 2004 from 3 European HF centers demonstrated that higher BF determined by DEXA was associated with lower mortality in patients with advanced HF; to our knowledge, these data have not yet been published in the peer-reviewed literature.29

We applaud Oreopoulos et al16 for their excellent study. Certainly, precise determinations of body composition may explain details of this puzzling obesity paradox in HF and other CV diseases. Currently, obesity clearly seems to be a predictor for the development of HF and most CV diseases. However, in cohorts with established CV diseases, including advanced HF, higher levels of BMI and BF currently appear to be protective.2,7-9,17

References

- 1.Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: an update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on obesity and heart disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation 2006;113(6):898-918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Ventura HO. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: risk factor, paradox, and impact of weight loss. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(21):1925-1932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2000. JAMA 2002;288(14):1723-1727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manson JE, Bassuk SS. Obesity in the United States: a fresh look at its high toll [editorial]. JAMA 2003;289(2):229-230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford ES, Capewell S. Coronary heart disease mortality among young adults in the U.S. from 1980 through 2002: concealed leveling of mortality rates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(22):2128-2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenchaiah S, Evans JC, Levy D, et al. Obesity and the risk of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(5):305-313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Artham SM, Lavie CJ, Patel HM, Ventura HO. Impact of obesity on the risk of heart failure and its prognosis. J Cardiometab Syndr. 2008;3(3):155-161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oreopoulos A, Padwal R, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Fonarow GC, Norris CM, McAlister FA. Body mass index and mortality in heart failure: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2008;156(1):13-22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonarow GC, Srikanthan P, Costanzo MR, et al. An obesity paradox in acute heart failure: analysis of body mass index and inhospital mortality for 108,927 patients in the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry. Am Heart J. 2007;153(1):74-81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, et al. Diagnostic performance of body mass index to detect obesity in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(17):2087-2093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romero-Corral A, Lopez-Jimenez F, Sierra-Johnson J, Somers VK. Differentiating between body fat and lean mass: how should we measure obesity? Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008;4(6):322-323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavie CJ, Sierra-Johnson J. Ergo-anthropometric assessment [letter reply]. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(10):941-942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health Understanding Adult Obesity. WIN Weight-control Information Network: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Web site NIH Publication No. 06-3680 November2008. http://www.win.niddk.nih.gov/publications/understanding.htm Accessed May 21, 2010

- 14.Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, et al. Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(6):959-966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romero-Corral A, Montori VM, Somers VK, et al. Association of bodyweight with total mortality and with cardiovascular events in coronary artery disease: a systematic review of cohort studies. Lancet 2006;368(9536):666-678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oreopoulos A, Ezekowitz JA, McAlister FA, et al. Association between direct measures of body composition and prognostic factors in chronic heart failure. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(7):609-617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavie CJ, Osman AF, Milani RV, Mehra MR. Body composition and prognosis in chronic systolic heart failure: the obesity paradox. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(7):891-894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Artham SM, Olivier AC, Ventura HO. Does body composition impact survival in patients with advanced heart failure [abstract 1713)]. Circulation 2007;116:II360 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt D, Salahudeen A. The obesity-survival paradox in hemodialysis patients: why do overweight hemodialysis patients live longer? Nutr Clin Pract. 2007;22(1):11-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Artham SM, Dharmendrakumar PA, Ventura HO. The obesity paradox, weight loss, and coronary disease. Am J Med. 2009;122(12):1106-1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavie CJ, Mehra MR, Milani RV. Obesity and heart failure prognosis: paradox or reverse epidemiology. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(1):5-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Block G, Horwich T, Fonarow GC. Reverse epidemiology of conventional cardiovascular risk factors in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(8):1439-1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anker SD, Negassa A, Coats AJ, et al. Prognostic importance of weight loss in chronic heart failure and the effect of treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: an observational study. Lancet 2003;361(9363):1077-1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rauchhaus M, Coats AJS, Anker SD. The endotoxin–lipoprotein hypothesis. Lancet 2000;356(9233):930-933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAuley PA, Kokkinos PF, Oliveira RB, Emerson BT, Myers JN. Obesity paradox and cardiorespiratory fitness in 12,417 male veterans aged 40 to 70 years. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(2):115-121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ades PA, Savage PD. The obesity paradox: perception vs knowledge [editorial]. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(2):112-114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arena R, Lavie CJ. The obesity paradox and outcome in heart failure: is excess bodyweight truly protective [editorial]? Future Cardiol. 2010;6(1):1-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lavie CJ, Ventura HO, Milani RV. The “obesity paradox”— is smoking/lung disease the explanation [editorial]? Chest 2008;134(5):896-898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cicoira M, Jankowska E, Doehner W, et al. Body composition and prognosis in 511 chronic heart failure patients: results from three European centers [abstract]. Eur J Heart Failure Suppl. 2004;3:49 [Google Scholar]