Abstract

Background

To examine the outcomes of highly-active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) for individuals with free access to healthcare, we evaluated 2327 patients in a cohort study composed of military personnel and beneficiaries with HIV infection who initiated HAART from 1996 to the end of 2007.

Methods

Outcomes analyzed were virologic suppression (VS) and failure (VF), CD4 count changes, AIDS and death. VF was defined as never suppressing or having at least one rebound event. Multivariate (MV) analyses stratified by the HAART initiation year (before or after 2000) were performed to identify risk factors associated with these outcomes.

Results

Among patients who started HAART after 2000, 81% had VS at 1 year (N = 1,759), 85% at 5 years (N = 1,061), and 82% at 8 years (N = 735). Five years post-HAART, the median CD4 increase was 247 cells/ml and 34% experienced VF. AIDS and mortality rates at 5 years were 2% and 0.3%, respectively. In a MV model adjusted for known risk factors associated with treatment response, being on active duty (versus retired) at HAART initiation was associated with a decreased risk of AIDS (HR = 0.6, 95% CI 0.4-1.0) and mortality (0.6, 0.3-0.9), an increased probability of CD4 increase ≥ 50% (1.2, 1.0-1.4), but was not significant for VF.

Conclusions

In this observational cohort, VS rates approach those described in clinical trials. Initiating HAART on active duty was associated with even better outcomes. These findings support the notion that free access to healthcare likely improves the response to HAART thereby reducing HIV-related morbidity and mortality.

Background

Despite substantial progress since the introduction of highly-active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) [1-4], maintaining virologic suppression is predominantly challenged by suboptimal antiretroviral (ARV) adherence. Studies have shown that difficulty with adherence is usually associated with (1) significant barriers to care, (2) ARV intolerability and (3) individual factors such as education, treatment fatigue, and the psychosocial context of the patient [5-7].

We sought to examine a large, multicenter cohort composed of military personnel and beneficiaries with HIV infection followed since diagnosis in order to illustrate the HAART outcomes for patients within a free-access healthcare system in the United States. The U.S. military medical system provides comprehensive HIV education, care and treatment, including the provision of ARVs and regular visits with HIV clinicians at medical treatment facilities (MTF), at no cost to the patient. Mandatory periodic HIV screening according to Department of Defense (DoD) policy [8] allows treatment initiation to be considered at an early stage of infection. Active duty personnel are required to attend the MTF at least twice yearly for formal medical evaluations. Following retirement from active duty, or separation for medical disability, all individuals retain health benefits and may continue participation in the cohort study while receiving their primary HIV care either within or outside of the military healthcare system.

Aside from the advantages afforded by the medical system, there are aspects of this cohort that allow for a unique perspective on HIV treatment response. The military population from which these patients are derived consists of highly motivated and disciplined individuals who possess either a minimum of a high school equivalent education (enlisted) or an undergraduate college degree (officers) and maintain rigorous physical standards [9-11]. As a consequence of periodic random drug screening, the reported rate of injection drug use (IDU) in this population is less than one percent [12]. Thus, many of the factors which typically hinder the clinical response to HAART in most North American cohorts [13-15], such as IDU, homelessness and unemployment, are minimized or eliminated in the military setting. Additionally, the cohort is racially balanced and geographically diverse reflecting the distribution of individuals with HIV in the U.S.[16]. As a separate aim, this cohort provided an opportunity to examine the relationship between demographic (e.g. race/ethnicity) and clinical factors (hepatitis B, prior STI, etc.) with outcomes after HAART in a U.S. population with fewer confounders related to access to care and IDU.

Methods

Study Participants

The U.S. Military HIV Natural History Study (NHS) is a prospective multicenter observational study of HIV-infected active duty military personnel and other beneficiaries (spouses, dependents, and retired military personnel) from the Army, Navy/Marines and Air Force. All participants provided written informed consent. The cohort characteristics have been previously described [17]. Patients were included in this analysis if they were enrolled in the NHS and initiated HAART at any time from 1996 until December 31, 2007 with data collected through July 1, 2008. The NHS has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of each participating center.

Definitions

Seroconverters (SC) were defined as patients having a documented HIV seronegative date prior to the first positive HIV date. The estimated date of seroconversion for SC was defined as the midpoint between the two dates. All CD4 count and VL measurements were done as part of routine clinical care. The clinically-approved methodology for this testing varied by site and over time. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) were defined as having a documented clinical history of gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis or herpes simplex at any time prior to initiation of HAART. Chronic hepatitis B co-infection was defined as having at least two positive hepatitis B surface antigen tests at least 6 months apart. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) co-infection was defined as having at least one positive HCV antibody test. ARV use referred to any antiretroviral therapy not meeting the NHS definition of HAART [17]. HAART initiation was the date when HAART was first prescribed. AIDS-defining illnesses were defined using the 1993 CDC classification but did not include CD4 count < 200 as an endpoint [18].

Statistical Analysis

Outcomes were described for all patients and separately for those initiating HAART from 1996-1999 (early HAART era, EHE) and for those starting HAART in 2000-2007 (late HAART era, LHE). Virologic outcomes and CD4 cell count response were described at 6-month intervals through 8 years after the initiation of HAART. Due to differing lengths of follow-up after HAART initiation, the sample size was 1063 (46%) at 5 years and 735 (32%) at 8 years. CD4 and viral load (VL) at HAART were the last recorded value up to 6-months before HAART. Six-month follow-up values where those recorded closest to the 6-month interval after HAART initiation (within a window of ± 3 months). Patients with missing laboratory values for a given time point were excluded from analyses at that time point. Virologic suppression (VS) was defined as an undetectable viral load (< 400 copies/mL). Virologic failure (VF) was defined as 2 consecutive VL detectable after VS (virologic rebound) or never achieving VS (never suppressed). Always suppressed was defined as having all measured VL undetectable for the entire period beginning 6 months after HAART initiation. CD4 count outcomes were expressed as the group mean and the mean increase after HAART initiation at a given time point. The percentage of patients who experienced at least a 30% or 50% CD4 count increase from HAART initiation was also determined. Switches and discontinuations of ARVs were not counted as failures.

Kaplan Meier (KM) life-table methods were used to estimate the cumulative rate of VF, CD4 increase of 50%, AIDS-defining conditions, and all-cause mortality. Patients without the event of interest were censored at the last recorded visit. For time-to-VF, patients never suppressed were considered to have failed at time zero. Stratified Cox-regression (by HAART initiation era and medical center) was used to determine the association of relevant covariates with these same outcomes. Baseline covariates used in the model were those found to be associated (p < 0.1) in univariate analyses as well as those shown to be risk factors in the literature.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Characteristics for patients who initiated HAART overall and by HAART initiation era are shown in Table 1. A total of 2,327 patients initiated HAART; 1,631 during the EHE and 696 during the LHE. Average follow-up after initiation of HAART was 6.2 years for all patients, 7.4 years in the EHE and 3.4 years in the LHE. The mean age at HAART start was 35 years overall and 9.5% were women. The race/ethnicity distribution was equally divided between African and European Americans (44% each); 8% were Hispanic and 4% were of other race/ethnicities. Overall, 213 (9.9%) were commissioned or warrant officers at study enrollment; 56% were active duty at time of HAART. The mean CD4 level at HAART start was 343 cells/mL and was similar in both eras. Patients in the LHE were more likely to be active duty, have a shorter duration between HIV diagnosis and HAART initiation, and less likely to have an AIDS-defining illness prior to HAART initiation, than those in the EHE.

Table 1.

Baseline Factors for Patients Initiating HAART in the Natural History Study

| Characteristic | Total (n = 2327) |

Early Initiation Era (n = 1631) |

Late Initiation Era (n = 696) |

P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age at HIV Diagnosis, years | 30.1 ± 8.1 | 29.8 ± 7.9 | 30.8 ± 8.6 | 0.007 |

| Age at HAART initiation, years | 34.7 ± 8.6 | 35.0 ± 8.2 | 34.1 ± 9.5 | 0.025 |

| Female | 221 (9.5%) | 169 (10.4%) | 52 (7.5%) | 0.029 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.188 | |||

| European American | 1024 (44.0%) | 730 (44.8%) | 294 (42.2%) | |

| African American | 1021 (43.9%) | 717 (44.0%) | 304 (43.7%) | |

| Hispanic | 194 (8.3%) | 130 (8.0%) | 64 (9.2%) | |

| Other | 88 (3.8%) | 54 (3.3%) | 34 (4.9%) | |

| Rank of Officer/Warrant at study enrollment | 213 (9.9%) | 143 (9.4%) | 70 (10.1%) | 0.606 |

| Active Duty at HAART initiation | 1293 (55.6%) | 773 (47.4%) | 520 (74.7%) | <0.001 |

| Medical History (prior to HAART Initiation) | ||||

| Year of HIV Diagnosis | 1994 ± 5.9 | 1992 ± 4.2 | 2000 ± 5.1 | <0.001 |

| HIV Diagnosis to HAART initiation, months | 44.2 (5.7 - 95.2) | 60.9 (16.9 - 103.8) | 10.1 (2.0 - 45.5) | <0.001 |

| Nadir CD4+ to HAART initiation, months | 3.3 (0.4 - 16.3) | 6.5 (0.7 - 19.4) | 0.8 (0.2 - 3.7) | <0.001 |

| Seroconverters (SC)a | 1691 (72.7%) | 1106 (67.8%) | 585 (84.1%) | <0.001 |

| Estimated date of SC to HIV Diagnosis, months | 8.1 (5.0 - 13.7) | 8.4 (5.3 - 14.4) | 7.4 (5.0 - 13.7) | 0.010 |

| Viral Load at HAART initiation, log10 copies/mL | 4.3 ± 1.0 | 4.3 ± 1.0 | 4.4 ± 0.9 | <0.001 |

| CD4+ at HIV Diagnosis, cells/mL | 499.7 ± 248.0 | 524.0 ± 252.1 | 448.0 ± 231.0 | <0.001 |

| CD4+ nadir, cells/mL | 283.2 ± 174.0 | 276.4 ± 183.3 | 299.6 ± 148.1 | 0.005 |

| CD4+ at HAART Initiation, cells/mL | 342.8 ± 211.6 | 341.0 ± 223.4 | 346.6 ± 184.8 | 0.590 |

| <200 | 459 (24.4%) | 357 (28.0%) | 102 (16.7%) | <0.001 |

| 200-349 | 581 (30.8%) | 331 (26.0%) | 250 (40.9%) | |

| 350+ | 845 (44.8%) | 586 (46.0%) | 259 (42.4%) | |

| Prior AIDS-Defining Event | 277 (11.9%) | 231 (14.2%) | 46 (6.6%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic Hepatitis B co-infection | 128 (6.1%) | 110 (7.4%) | 18 (2.9%) | <0.001 |

| Hepatitis C co-infection | 121 (6.1%) | 99 (7.1%) | 22 (3.6%) | 0.002 |

| Prior Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI) | 1058 (45.5%) | 839 (51.4%) | 219 (31.5%) | <0.001 |

| ARV Use (mono- or dual-therapy) | 1224 (52.6%) | 1121 (68.7%) | 103 (14.8%) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 14.1 ± 1.6 | 13.9 ± 1.6 | 14.4 ± 1.4 | <0.001 |

| ALT, μ/L | 47.1 ± 53.7 | 48.2 ± 52.9 | 45.1 ± 55.2 | 0.336 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | <0.001 |

| Initial HAART Regimen | ||||

| Unboosted PI | 1320 (56.7%) | 1261 (77.3%) | 59 (8.5%) | <0.001 |

| Boosted PI | 205 (8.8%) | 121 (7.4%) | 84 (12.1%) | |

| NNRTI | 622 (26.7%) | 169 (10.4%) | 453 (65.1%) | |

| PI + NNRTI + NRTI | 86 (3.7%) | 71 (4.4%) | 15 (2.2%) | |

| 3 NRTI | 94 (4.0%) | 9 (0.6%) | 85 (12.2%) |

Median (IQR) is presented for duration factors given in months

a Percentage of patients who are known seroconverters

b Late versus Early HAART initiation era

Antiretroviral Use

As expected, both prior ARV use and initial HAART regimen differed significantly (p < 0.001) between eras (Table 1, Figure 1A). Nearly 69% of patients in the EHE had prior ARV use compared to 15% in the LHE (p < 0.001). In the EHE, 85% used a PI-containing (77% unboosted) initial HAART regimen whereas in the LHE, 65% used an NNRTI-containing initial regimen (predominantly efavirenz). Of the 2,327 patients initiating their first HAART regimen, 557 (24%) remained on the same regimen for the entire duration of follow up; 53.5% were on their initial regimen at one-year (Figure 1B). At the end of follow-up, 84% were still on HAART. Of those still on HAART, 23% were on an unboosted PI, 23% were on a boosted-PI, and 27% were on a NNRTI. During the follow-up period, patients were on HAART an average of 93% of the time.

Figure 1.

HAART usage in the Natural History Study. (A) Distribution of prior ARV use and first regimen type by year of HAART initiation with duration of HIV infection prior to HAART start for seroconverters. (B) Therapy changes over time. The declining percentage of patients remaining on the first HAART regimen results from complete discontinuation of or changes in therapy.

VL, CD4 and Clinical Outcomes

The percentage of patients with VS (Table 2) was higher in the LHE compared to the EHE throughout follow-up (p < 0.001). One year after HAART initiation, 57% and 81% of patients with available viral loads had VS in the EHE and LHE, respectively. Restricting analyses to active duty patients, these percentages were slightly higher (64% and 84%, respectively). The percentage of patients with VS at 5 years was 59% and 85%, and at 8 years was 65% and 82% for the EHE and LHE, respectively. Analyses restricted to active duty patients showed nearly identical results at these time points. The cumulative percentage of patients who achieved an undetectable viral load ever within 5 years after HAART initiation was 93.2%. In a subset of patients where self-reported adherence was available within 15 months of HAART start (n = 133), over 94% reported ≥ 90% adherence. A cross-sectional assessment of adherence for all patients in the cohort on HAART (n = 1050) demonstrated over 90% reporting ≥ 90% adherence.

Table 2.

Virologic and Immunologic Outcomes for patients initiating HAART using an Intention to Treat Analysis.

| Outcome | 1 year | 5 years | 8 years | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAART Era | Total | Early | Late | Total | Early | Late | Total | Early | Late |

| Median (IQR) # of viral loads available per patient | 4 (3-6) | 4 (3-6) | 5 (3-6) | 17 (12-23) | 18 (12-24) | 15 (12-19) | 26 (18-35) | 26 (18-35) | 20 (15-27) |

| Virologic Suppression (n) | 1759 | 1216 | 543 | 1063 | 868 | 195 | 735 | 707 | 28 |

| Suppresseda | 1135 (64.5) | 693 (57.0)g | 442 (81.4) | 674 (63.4) | 508 (58.5)g | 166 (85.1) | 487 (66.3) | 464 (65.6) | 23 (82.1) |

| Always Suppressedb | 864 (49.1) | 478 (39.3)g | 386 (71.1) | 244 (23.0) | 172 (19.8)g | 72 (36.9) | 112 (15.2) | 104 (14.7) | 8 (28.6) |

| Ever Suppressedc | 1391 (79.1) | 890 (73.2) | 501 (92.3) | 991 (93.2) | 800 (92.2) | 191 (97.9) | 707 (96.2) | 680 (96.2) | 27 (96.4) |

| Virologic Failured | 629 (35.8) | 525 (43.2)g | 104 (19.2) | 594 (55.9) | 527 (60.7)g | 67 (34.4) | 496 (67.5) | 482 (68.2)g | 14 (50. 0) |

| Never Suppressede | 368 (20.9) | 326 (26.8)g | 42 (7.7) | 72 (6.8) | 68 (7.8)g | 4 (2.1) | 28 (3.8) | 27 (3.8) | 1 (3.6) |

| Reboundf | 261 (14.8) | 199 (16.4)g | 62 (11.4) | 522 (49.1) | 459 (52.9)g | 63 (32.3) | 468 (63.7) | 455 (64.4) | 13 (46.4) |

| Mean CD4, cells/mL | 488 ± 267 | 469 ± 268 | 530 ± 262 | 571 ± 306 | 562 ± 305 | 611 ± 307 | 556 ± 306 | 552 ± 301 | 657 ± 398 |

| CD4 Change | 143 ± 180 | 126 ± 171g | 179 ± 193 | 220 ± 271 | 214 ± 270 | 247 ± 278 | 209 ± 288 | 206 ± 284 | 263 ± 362 |

| CD4 Increase ≥ 30% | 880 (60.0) | 564 (56.9) | 316 (66.5) | 583 (66.9) | 461 (65.3) | 122 (73.5) | 381 (62.5) | 365 (62.6) | 16 (59.3) |

| CD4 Increase ≥ 50% | 665 (45.4) | 418 (42.2) | 247 (52.0) | 489 (56.1) | 385 (54.5) | 104 (62.7) | 331 (54.3) | 318 (54.5) | 13 (48.1) |

Patients with missing lab values were excluded on that date

aNumber (%) of patients at the given time point who have one undetectable viral load

bNumber (%) of patients suppressed at 6-months and then at all visits through indicated time point

cNumber (%) of patients having an undetectable viral load at least once through indicated time point

dNumber (%) of patients at the given time point who have either had at least one episode of rebound or never suppressed

eNumber (%) of patients never having an undetectable viral load

fNumber (%) of patients ever having a rebound event (undetectable, then detectable + detectable)

gSignificant difference comparing early versus late era (p < 0.05)

There were also significant differences between the eras in the percentage of patients who were always suppressed, never suppressed or had at least one virologic rebound event throughout the study period. At 1 year, 19% of patients in the LHE experienced VF (versus 43% EHE). For this same era at 5 and 8 years, there were 34% and 50% of LHE patients (versus 61% and 68% EHE), respectively. Similarly, the degree of immune reconstitution was greater in the LHE, despite similar CD4 levels at HAART start. In the first year, 52% of patients from the LHE had achieved a 50% gain in CD4 count. This increased to 63% of patients at 5 years.

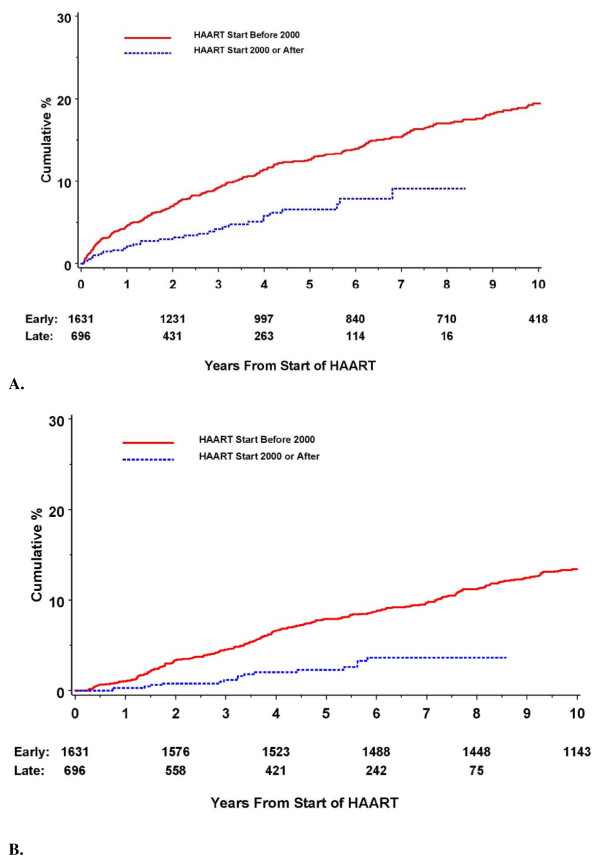

The rate of AIDS events and deaths were lower in the LHE compared to the EHE. At 1 year, the AIDS event rate (Figure 2) was 4.7% for patients in the EHE and 2.0% for patients in the LHE; the mortality rates were 1.0% and 0.3%, respectively. These rates remained low and the differences persisted throughout the study period.

Figure 2.

KM curves for cumulative clinical outcomes for patients after HAART initiation stratified by HAART Era. (A) First AIDS event (B) Mortality.

Predictors of Response to HAART

In a multivariate model (Table 3) stratified by HAART initiation era and MTF that included age, gender, ethnicity, active duty status, military rank, CD4 count, VL, duration of HIV infection, prior ARV use, initial HAART regimen, STIs, hepatitis B and C co-infection and Hgb, the factors significantly (p < 0.05) associated with VF were younger age at HAART initiation, African-American ethnicity, higher VL at HAART initiation, prior use of ARVs, and no prior history of STI. The factors significantly associated with achieving a CD4 cell gain of at least 50% were being on active duty at HAART start, lower CD4 count at HAART start, shorter duration of HIV infection, and no prior ARV use. Ethnicity nearly reached significance for this outcome. Risk factors associated with AIDS events after HAART were younger age, male gender, lower CD4 count, and prior AIDS events. Non-active duty status and duration of HIV infection showed a trend towards significance. Factors associated with higher mortality included non-active duty status, lower CD4 count at HAART initiation, higher VL at HAART initiation, HCV co-infection, and lower Hgb. No difference was seen when comparing PI to NNRTI use as the first regimen. Although patients on active duty had better clinical and immunologic outcomes as well as a higher likelihood of VS (data not shown), no difference was found with time to VF.

Table 3.

Predictors of Time to Development of Outcomes after initiating HAART Using Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards.

| Risk Factor | Virologic Failure N = 1307 |

CD4 Responsea N = 1375 |

AIDS N = 1375 |

Mortality N = 1376 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age HAART start, 10 yrs | 0.8 (0.7-0.9), <0.001 | 1.1 (1.0-1.2), 0.088 | 0.7 (0.6-0.9), 0.019 | 1.1 (0.8-1.4), 0.649 |

| Gender, Women vs Men | 1.2 (0.8-1.6), 0.381 | 1.0 (0.8-1.3), 0.987 | 0.3 (0.1-1.0), 0.042 | 0.6 (0.2-1.5), 0.240 |

| Ethnicity, AA vs EAb | 1.2 (1.0-1.5), 0.015 | 0.9 (0.8-1.0), 0.056 | 1.2 (0.8-1.8), 0.378 | 0.9 (0.6-1.4), 0.773 |

| Active Duty, yes vs no | 1.1 (0.9-1.4), 0.269 | 1.2 (1.0-1.4), 0.036 | 0.6 (0.4-1.0), 0.051 | 0.6 (0.3-0.9), 0.021 |

| Rank, Enlisted vs Officerb | 1.1 (0.8-1.4), 0.710 | 1.0 (0.8-1.3), 0.677 | 1.0 (0.5-1.8), 0.877 | 1.3 (0.7-2.6), 0.427 |

| CD4 at initiation, 50 cells | 1.0 (1.0-1.0), 0.765 | 0.9 (0.8-0.9), <0.001 | 0.9 (0.8-0.9), <0.001 | 0.9 (0.8-1.0), 0.003 |

| VL at initiation, 1 log | 1.2 (1.1-1.3), <0.001 | 1.1 (1.0-1.2), 0.074 | 1.1 (0.9-1.4), 0.352 | 1.4 (1.1-1.8), 0.007 |

| Duration of HIV, 5 years | 1.1 (1.0-1.23), 0.203 | 0.9 (0.8-0.9), <0.006 | 1.3 (1.0-1.8), 0.059 | 1.1 (0.8-1.5), 0.702 |

| Prior AIDS, yes vs no | 1.0 (0.8-1.4), 0.944 | 1.0 (0.8-1.3), 0.998 | 1.6 (1.1-2.5), 0.048 | 1.4 (0.9-2.2), 0.179 |

| Prior ARV use, yes vs no | 1.7 (1.4-2.1), <0.001 | 0.7 (0.6-0.8), <0.001 | 1.6 (0.9-2.8), 0.116 | 1.5 (0.8-3.0), 0.195 |

| Regimen, NNRTI vs PIb | 0.8 (0.7-1.1), 0.181 | 0.9 (0.8-1.1), 0.517 | 0.7 (0.3-1.3), 0.250 | 1.6 (0.8-3.0), 0.165 |

| STI After HIV, yes vs no | 0.8 (0.7-1.0), 0.048 | 1.0 (0.9-1.1), 0.820 | 1.1 (0.7-1.6), 0.699 | 1.0 (0.6-1.4), 0.806 |

| Hepatitis B, yes vs no | 1.1 (0.8-1.4), 0.733 | 0.9 (0.7-1.2), 0.454 | 1.1 (0.7-1.9), 0.667 | 1.2 (0.6-2.1), 0.612 |

| Hepatitis C, yes vs no | 1.2 (0.9-1.7), 0.242 | 1.3 (1.0-1.7), 0.079 | 1.4 (0.8-2.5), 0.250 | 1.9 (1.1-3.3), 0.026 |

| Hgb, 2 mg/dl | 1.0 (0.9-1.1), 0.774 | 0.9 (0.8-1.0), 0.089 | 0.8 (0.6-1.0), 0.111 | 0.7 (0.6-0.9), 0.009 |

Displayed are the hazard ratios, 95% confidence intervals and p values. The analyses are stratified by treatment era and medical treatment facility.

HAART - Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy; VL - Viral load; CD4 - CD4 count; ARV - Antiretroviral; AA - African American; EA - European American, STI - Sexually Transmitted Infection; Hgb - Hemoglobin; bold = p < 0.05

aHazard Ratio of patients able to achieve CD4 cell increase of at least 50% from the baseline CD4 count

bAdditional categories examined but not displayed: for ethnicity, other vs EA; for rank, others vs officer; for regimen, neither vs PI and both vs PI

Discussion

In this study, we describe the clinical characteristics and response to HAART among HIV-infected military personnel and beneficiaries initiating treatment over the course of twelve years (1996-2007) with an average follow-up of over 6 years. The NHS is conducted within the military medical system allowing for an evaluation of HAART response in a U.S. clinical setting with free and open access to healthcare and medications.

After stratifying patients into two HAART initiation eras, 1996-2000 (EHE) and 2000 onward (LHE), it was evident that these eras differed significantly for several reasons. First, the large majority of patients starting treatment in the EHE had prior exposure to suboptimal therapy which has been shown to compromise the response to HAART [19-21]. Secondly, more potent regimens were available in the LHE. Additionally, more patients in the EHE had a prior AIDS-defining illness likely impacting response [22,23]. Furthermore, those who survived the pre-HAART era long enough to initiate HAART may have intrinsic host factors which could impact outcomes [24]. Finally, there were significant differences in the timing of HAART initiation between both eras (duration of HIV diagnosis to HAART initiation and baseline CD4 count). This likely reflects differences in treatment guideline recommendations that were followed in each era and the fact that many patients starting HAART in the EHE became infected well before the availability of HAART. Despite the challenges experienced by participants initiating in the EHE, the percent virologically suppressed was around 60% throughout the duration of follow up.

For the LHE patients in this cohort, the virologic and immunologic responses were similar to those reported by randomized clinical trials using a regimen containing either efavirenz or a boosted-PI. A meta-analysis of 20 clinical trials by Gupta et al. described a VS rate of 76% and CD4 change of 176 cells/mL at 48 weeks [25]. The rates we observed were equivalent or slightly higher than these and were sustained for more than 5 years. Limited population and cohort studies in the U.S. have shown variable VS rates at 3 to 8 months of 50-85% and rebound at 3 years of 20-50% [26,27]. Outside the U.S., several cohorts with universal access to healthcare have demonstrated a remarkable response to HAART when compared to cohorts with similar demographics in the U.S.[3,28-31]. The Swiss HIV Cohort Study reported an overall ITT VS rate of 89% and a CD4 increase of 177 cells/mL at 12 months after HAART initiation for ARV naïve patients during this same LHE [32]. In this same analysis, the percentage of patients having a change or discontinuation within the first year of ART for any reason was 44.3-48.8% (varying by era) which is comparable to patients in the NHS.

Although there are drug assistance programs in the U.S. for eligible individuals with HIV/AIDS, the delay before medical care becomes available can postpone HAART initiation, and even the minimal associated costs can be a significant barrier for some patients [33,34]. Co-payments and fees can reduce adherence and have been shown to increase mortality [35-37]. It is important to note, however, that universal access to care and free medications are insufficient to ensure that all patients will achieve treatment success. Joy et al. described a population in Vancouver, Canada that has open access to healthcare but found that poverty, unemployment and a lack of post-secondary education impacted on survival in the HAART era [38-40].

This cohort provided an opportunity to examine the relationship between demographic and clinical factors with outcomes after HAART in a clinical setting that minimized confounding related to access to care and IDU. Previously, we and others have shown associations between both age at HAART initiation [41] and ethnicity [17,42,43] with treatment response. Concordant with other studies, viral load was a predictor of VF and mortality and CD4 count was a predictor of immune reconstitution, AIDS events, and mortality [44-46]. The CD4 recovery was greatest for those with lower baseline CD4 counts similar to findings by Hunt et al. [47] which likely reflects the endpoint used in this analysis (50% increase). We also showed an association between the duration of HIV infection and CD4 reconstitution [48] in addition to increased AIDS events despite a lack of evidence for these findings in a previous prospective study [49]. Although conflicting findings abound in the literature with respect to gender differences in HAART response [50], in the present study, women had a longer time to AIDS as compared to men (consistent with several similar reports [51-54]). Surprisingly, among all subjects the initial regimen type was not found to be a significant predictor of VF [55]. Although this analysis did not distinguish among the NNRTIs or boosted-PIs from unboosted-PIs, the era stratification accounted for differences in drug potency. Interestingly in our study, patients with a prior STI had a lower rate of VF. This is in contrast to studies showing a higher incidence of STIs being associated with non-adherence [56-58] or a negative impact on VL and CD4 count likely via increased immune activation [59].

Active duty status was associated with improved survival, immune reconstitution and a lower rate of AIDS-defining events. Although a distinctive factor in our cohort, important implications related to adherence and general health can be proposed as to why individuals on active duty had improved outcomes; some of which could be translated to other settings. Factors that might improve an active duty member's medication adherence include: (1) better access to ARVs, (2) closer clinical monitoring, and (3) a more disciplined and regimented environment. Although all participants in this cohort study do have free access to the DoD healthcare system, retirees can live further from network facilities and can choose private insurance resulting in copayments for ARVs. Furthermore, active duty personnel may be more closely monitored as they are required by their supervisors to seek medical care on a regular basis. As evidence, research study visit attendance has been shown to be significantly greater for active duty vs. others [17]. General health may be better among active duty members because of physical fitness requirements, lower rates of substance abuse, and a cultural awareness of the benefits of health and nutrition [4,29,60]. Additional factors such as stable employment and guaranteed housing may also contribute to better outcomes. Finally, the goal of remaining on active duty itself is an incentive to stay healthy. HIV-infected military personnel can remain on active duty and continue working, but the development of an AIDS-defining illness can lead to medical separation with retention of health benefits. Although the MV analysis adjusted for several clinical factors such as previous AIDS event, it is possible that non-active duty status is a marker for poorer health. This is substantiated by the fact that 28% of non-active duty patients were retired for medical reasons prior to the start of HAART.

One limitation of this study is that medication adherence data were unavailable for most patients (adherence questionnaires were added to the data collection in 2006). The relative impact of HIV drug resistance was also not assessed in this study. Finally, a disadvantage of any cohort study is that these results cannot be readily extrapolated to other clinical settings where rates of IDU, demographic characteristics, and access to healthcare differ. However, this cohort does provide an opportunity to observe sustainable treatment success after early HAART initiation under these conditions.

Conclusions

In summary, we find rates of VS and CD4 reconstitution to be high and clinical events to be low for DoD beneficiaries receiving treatment for HIV. These rates approach those reported in clinical trials. Active duty personnel have better immunologic and clinical outcomes but equivalent rates of VF to other beneficiaries. These findings support the notion that free and open access to healthcare provides a favorable environment for optimizing HIV treatment outcomes.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

The following authors were involved in study conception and design: VCM, GG, ACW, BKA; acquisition of data: VCM, ACW, HC, MLL, AG, JFO, NCC, RJO, GWW, BKA; analysis and interpretation of data: VCM, GG, ACW, BKA; manuscript drafting and critical revision: VCM, GG, ACW, MLL, AG, JFO, NCC, RJO, AL, GWW, BKA. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Vincent C Marconi, Email: vcmarco@emory.edu.

Greg A Grandits, Email: greg-g@ccbr.umn.edu.

Amy C Weintrob, Email: AMY.WEINTROB@us.army.mil.

Helen Chun, Email: helen.chun@med.navy.mil.

Michael L Landrum, Email: mlandrum@idcrp.org.

Anuradha Ganesan, Email: Anuradha.Ganesan@med.navy.mil.

Jason F Okulicz, Email: Jason.Okulicz@amedd.army.mil.

Nancy Crum-Cianflone, Email: Nancy.Crum@med.navy.mil.

Robert J O'Connell, Email: roconnell@hivresearch.org.

Alan Lifson, Email: lifso001@umn.edu.

Glenn W Wortmann, Email: GLENN.WORTMANN@us.army.mil.

Brian K Agan, Email: bagan@idcrp.org.

the Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program HIV Working Group (IDCRP), Email: bagan@idcrp.org.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank our patients for their enormous contributions over the years and the IDCRP HIV Working Group: Susan Banks, Mary Bavaro, MD, Cathy Decker, MD, Anne Eaton, BA, Connor Eggleston, Patricia Grambsch, PhD, Cliff Hawkes, MD, Linda Jagodzinski, PhD, Arthur Johnson, MD, Jason Maguire, MD, Scott Merritt, Sheila Peel, PhD, Michael Polis, MD, John Powers, MD, Roseanne A. Ressner, MD, Ken Svendsen, MS, Edmund Tramont, MD, Sybil Tasker, MD, Mark R. Wallace, MD, Timothy Whitman, MD, Michael Zapor, MD. We would also like to thank David Bangsberg, MD for his critical review of this manuscript.

Support for this work (IDCRP-000-03) was provided by the Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program (IDCRP), a Department of Defense (DoD) program executed through the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. This project has been funded in whole, or in part, with federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH), under Inter-Agency Agreement Y1-AI-5072. This support included study design, data collection, analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing, and submission.

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the NIH or the Department of Health and Human Services, the DoD or the Departments of the Army, Navy or Air Force. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

This work is original and has not been published elsewhere. Portions were presented at the 16th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Montreal, Canada (Abstract #582).

References

- Moore DM, Hogg RS, Yip B, Wood E, Tyndall M, Braitstein P, Montaner JS. Discordant immunologic and virologic responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy are associated with increased mortality and poor adherence to therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:288–293. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000182847.38098.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan R, Westfall AO, Willig JH, Mugavero MJ, Saag MS, Kaslow RA, Kempf MC. Clinical outcome of HIV-infected antiretroviral-naive patients with discordant immunologic and virologic responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:553–558. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31816856c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit C, Geskus R, Walker S, Sabin C, Coutinho R, Porter K, Prins M. Effective therapy has altered the spectrum of cause-specific mortality following HIV seroconversion. Aids. 2006;20:741–749. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216375.99560.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessol NA, Kalinowski A, Benning L, Mullen J, Young M, Palella F, Anastos K, Detels R, Cohen MH. Mortality among participants in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study and the Women's Interagency HIV Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:287–294. doi: 10.1086/510488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, Wu AW. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) AIDS Care. 2000;12:255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds NR, Testa MA, Marc LG, Chesney MA, Neidig JL, Smith SR, Vella S, Robbins GK. Factors influencing medication adherence beliefs and self-efficacy in persons naive to antiretroviral therapy: a multicenter, cross-sectional study. AIDS Behav. 2004;8:141–150. doi: 10.1023/B:AIBE.0000030245.52406.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivers LC, Kendrick D, Doucette K. Efficacy of antiretroviral therapy programs in resource-poor settings: a meta-analysis of the published literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:217–224. doi: 10.1086/431199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista CT, Sateren WB, Sanchez JL, Rathore Z, Singer DE, Birx DL, Scott PT. HIV incidence trends among white and african-american active duty United States Army personnel (1986-2003) J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:351–355. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243051.35204.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapik JJ, Sharp MA, Darakjy S, Jones SB, Hauret KG, Jones BH. Temporal changes in the physical fitness of US Army recruits. Sports Med. 2006;36:613–634. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200636070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KL, Mahmoud RA, Krauss MR, Kelley PW, Grubb LK, Ostroski MR. Reducing medical attrition: the role of the Accession Medical Standards Analysis and Research Activity. Mil Med. 1999;164:485–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapik JJ, Canham-Chervak M, Hoedebecke E, Hewitson WC, Hauret K, Held C, Sharp MA. The fitness training unit in U.S. Army basic combat training: physical fitness, training outcomes, and injuries. Mil Med. 2001;166:356–361. doi: 10.1093/milmed/166.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodine SK, Starkey MJ, Shaffer RA, Ito SI, Tasker SA, Barile AJ, Tamminga CL, Stephan KT, Aronson NE, Fraser SL. Diverse HIV-1 subtypes and clinical, laboratory and behavioral factors in a recently infected US military cohort. Aids. 2003;17:2521–2527. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200311210-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyndall MW, McNally M, Lai C, Zhang R, Wood E, Kerr T, Montaner JG. Directly observed therapy programmes for anti-retroviral treatment amongst injection drug users in Vancouver: access, adherence and outcomes. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Montaner JS, Yip B, Tyndall MW, Schechter MT, O'Shaughnessy MV, Hogg RS. Adherence and plasma HIV RNA responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-1 infected injection drug users. Cmaj. 2003;169:656–661. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastos K, Barron Y, Miotti P, Weiser B, Young M, Hessol N, Greenblatt RM, Cohen M, Augenbraun M, Levine A, Munoz A. Risk of progression to AIDS and death in women infected with HIV-1 initiating highly active antiretroviral treatment at different stages of disease. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1973–1980. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.17.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM, Karon J, Brookmeyer R, Kaplan EH, McKenna MT, Janssen RS. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. Jama. 2008;300:520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintrob AC, Grandits GA, Agan BK, Ganesan A, Landrum ML, Crum-Cianflone NF, Johnson EN, Ordonez CE, Wortmann GW, Marconi VC. Virologic response differences between African Americans and European Americans initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy with equal access to care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:574–580. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b98537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. Jama. 1993;269:729–730. doi: 10.1001/jama.269.6.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabar S, Pradier C, Le Corfec E, Lancar R, Allavena C, Bentata M, Berlureau P, Dupont C, Fabbro-Peray P, Poizot-Martin I, Costagliola D. Factors associated with clinical and virological failure in patients receiving a triple therapy including a protease inhibitor. Aids. 2000;14:141–149. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200001280-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Moing V, Chene G, Carrieri MP, Alioum A, Brun-Vezinet F, Piroth L, Cassuto JP, Moatti JP, Raffi F, Leport C. Predictors of virological rebound in HIV-1-infected patients initiating a protease inhibitor-containing regimen. Aids. 2002;16:21–29. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann GR, Bloch M, Zaunders JJ, Smith D, Cooper DA. Long-term immunological response in HIV-1-infected subjects receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2000;14:959–969. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200005260-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, May M, Chene G, Phillips AN, Ledergerber B, Dabis F, Costagliola D, D'Arminio Monforte A, de Wolf F, Reiss P. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:119–129. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet F, Thiebaut R, Chene G, Neau D, Pellegrin JL, Mercie P, Beylot J, Dabis F, Salamon R, Morlat P. Determinants of clinical progression in antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy. Aquitaine Cohort, France, 1996-2002. HIV Med. 2005;6:198–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2005.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja SK, Kulkarni H, Catano G, Agan BK, Camargo JF, He W, O'Connell RJ, Marconi VC, Delmar J, Eron J. CCL3L1-CCR5 genotype influences durability of immune recovery during antiretroviral therapy of HIV-1-infected individuals. Nat Med. 2008;14:413–420. doi: 10.1038/nm1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Hill A, Sawyer AW, Pillay D. Emergence of drug resistance in HIV type 1-infected patients after receipt of first-line highly active antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review of clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:712–722. doi: 10.1086/590943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson LP, Phair JP, Yamashita TE. Virologic and immunologic response to highly active antiretroviral therapy. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2004;1:74–81. doi: 10.1007/s11904-004-0011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AN, Staszewski S, Weber R, Kirk O, Francioli P, Miller V, Vernazza P, Lundgren JD, Ledergerber B. HIV viral load response to antiretroviral therapy according to the baseline CD4 cell count and viral load. Jama. 2001;286:2560–2567. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.20.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Hogg RS, Yip B, Moore D, Harrigan PR, Montaner JS. Superior virological response to boosted protease inhibitor-based highly active antiretroviral therapy in an observational treatment programme. HIV Med. 2007;8:80–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Ledergerber B, Tilling K, Weber R, Sendi P, Rickenbach M, Robins JM, Egger M. Long-term effectiveness of potent antiretroviral therapy in preventing AIDS and death: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2005;366:378–384. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krentz HB, Kliewer G, Gill MJ. Changing mortality rates and causes of death for HIV-infected individuals living in Southern Alberta, Canada from 1984 to 2003. HIV Med. 2005;6:99–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2005.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill VS, Lima VD, Zhang W, Wynhoven B, Yip B, Hogg RS, Montaner JS, Harrigan PR. Improved virological outcomes in British Columbia concomitant with decreasing incidence of HIV type 1 drug resistance detection. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:98–105. doi: 10.1086/648729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo TT, Ledergerber B, Keiser O, Hirschel B, Furrer H, Battegay M, Cavassini M, Bernasconi E, Vernazza P, Weber R. Durability and outcome of initial antiretroviral treatments received during 2000--2005 by patients in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1685–1694. doi: 10.1086/588141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linas BP, Zheng H, Losina E, Rockwell A, Walensky RP, Cranston K, Freedberg KA. Optimizing resource allocation in United States AIDS drug assistance programs. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1357–1364. doi: 10.1086/508657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl W, Schmid C. The AIDS Drug Assistance Program: Securing HIV/AIDS Drugs for the Nation's Poor and Uninsured. Book The AIDS Drug Assistance Program: Securing HIV/AIDS Drugs for the Nation's Poor and Uninsured (Editor ed.^eds.). City. 2009.

- Stone VE, Jordan J, Tolson J, Miller R, Pilon T. Perspectives on adherence and simplicity for HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy: self-report of the relative importance of multiple attributes of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimens in predicting adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36:808–816. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200407010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Myer L, Bangsberg DR, Boulle A, Nash D, Schechter M, Laurent C, Keiser O, May M. Early loss of HIV-infected patients on potent antiretroviral therapy programmes in lower-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:559–567. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.044248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Schechter M, Boulle A, Miotti P, Wood R, Laurent C, Sprinz E, Seyler C. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet. 2006;367:817–824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joy R, Druyts EF, Brandson EK, Lima VD, Rustad CA, Zhang W, Wood E, Montaner JS, Hogg RS. Impact of neighborhood-level socioeconomic status on HIV disease progression in a universal health care setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:500–505. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181648dfd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Montaner JS, Chan K, Tyndall MW, Schechter MT, Bangsberg D, O'Shaughnessy MV, Hogg RS. Socioeconomic status, access to triple therapy, and survival from HIV-disease since 1996. Aids. 2002;16:2065–2072. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200210180-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser SD, Frongillo EA, Ragland K, Hogg RS, Riley ED, Bangsberg DR. Food insecurity is associated with incomplete HIV RNA suppression among homeless and marginally housed HIV-infected individuals in San Francisco. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:14–20. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0824-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintrob AC, Fieberg AM, Agan BK, Ganesan A, Crum-Cianflone NF, Marconi VC, Roediger M, Fraser SL, Wegner SA, Wortmann GW. Increasing age at HIV seroconversion from 18 to 40 years is associated with favorable virologic and immunologic responses to HAART. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:40–47. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31817bec05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence BW, Ostermann J, Kumar V, Whetten K, Thielman N, Mugavero MJ. The influence of psychosocial characteristics and race/ethnicity on the use, duration, and success of antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:194–201. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815ace7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverberg MJ, Wegner SA, Milazzo MJ, McKaig RG, Williams CF, Agan BK, Armstrong AW, Gange SJ, Hawkes C, O'Connell RJ. Effectiveness of highly-active antiretroviral therapy by race/ethnicity. Aids. 2006;20:1531–1538. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000237369.41617.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes R, Mocroft A, Kirk O, Lazzarin A, Barton SE, van Lunzen J, Katzenstein TL, Antunes F, Lundgren JD, Clotet B. Predictors of virological success and ensuing failure in HIV-positive patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy in Europe: results from the EuroSIDA study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1123–1132. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.8.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JE, Hanson DL, Cohn DL, Karon J, Buskin S, Thompson M, Fleming P, Dworkin MS. When to begin highly active antiretroviral therapy? Evidence supporting initiation of therapy at CD4+ lymphocyte counts <350 cells/microL. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:951–958. doi: 10.1086/377606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarwater PM, Gallant JE, Mellors JW, Gore ME, Phair JP, Detels R, Margolick JB, Munoz A. Prognostic value of plasma HIV RNA among highly active antiretroviral therapy users. Aids. 2004;18:2419–2423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt PW, Deeks SG, Rodriguez B, Valdez H, Shade SB, Abrams DI, Kitahata MM, Krone M, Neilands TB, Brand RJ. Continued CD4 cell count increases in HIV-infected adults experiencing 4 years of viral suppression on antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2003;17:1907–1915. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann GR, Furrer H, Ledergerber B, Perrin L, Opravil M, Vernazza P, Cavassini M, Bernasconi E, Rickenbach M, Hirschel B, Battegay M. Characteristics, determinants, and clinical relevance of CD4 T cell recovery to <500 cells/microL in HIV type 1-infected individuals receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:361–372. doi: 10.1086/431484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezzotti P, Pappagallo M, Phillips AN, Boros S, Valdarchi C, Sinicco A, Zaccarelli M, Rezza G. Response to highly active antiretroviral therapy according to duration of HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;26:473–479. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200104150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicastri E, Leone S, Angeletti C, Palmisano L, Sarmati L, Chiesi A, Geraci A, Vella S, Narciso P, Corpolongo A, Andreoni M. Sex issues in HIV-1-infected persons during highly active antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:724–732. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collazos J, Asensi V, Carton JA. Sex differences in the clinical, immunological and virological parameters of HIV-infected patients treated with HAART. Aids. 2007;21:835–843. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280b0774a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall HI, McDavid K, Ling Q, Sloggett A. Determinants of progression to AIDS or death after HIV diagnosis, United States, 1996 to 2001. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:824–833. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferradini L, Jeannin A, Pinoges L, Izopet J, Odhiambo D, Mankhambo L, Karungi G, Szumilin E, Balandine S, Fedida G. Scaling up of highly active antiretroviral therapy in a rural district of Malawi: an effectiveness assessment. Lancet. 2006;367:1335–1342. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calmy A, Pinoges L, Szumilin E, Zachariah R, Ford N, Ferradini L. Generic fixed-dose combination antiretroviral treatment in resource-poor settings: multicentric observational cohort. Aids. 2006;20:1163–1169. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000226957.79847.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna N, Opravil M, Furrer H, Cavassini M, Vernazza P, Bernasconi E, Weber R, Hirschel B, Battegay M, Kaufmann GR. CD4+ T cell count recovery in HIV type 1-infected patients is independent of class of antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1093–1101. doi: 10.1086/592113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton WN, Chen CY, Conti DJ, Schultz AB, Edington DW. The association of antidepressant medication adherence with employee disability absences. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13:105–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Rompa D. HIV treatment adherence and unprotected sex practices in people receiving antiretroviral therapy. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:59–61. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Eaton L, Cain D, Cherry C, Pope H, Kalichman M. HIV treatment beliefs and sexual transmission risk behaviors among HIV positive men and women. J Behav Med. 2006;29:401–410. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchacz K, Patel P, Taylor M, Kerndt PR, Byers RH, Holmberg SD, Klausner JD. Syphilis increases HIV viral load and decreases CD4 cell counts in HIV-infected patients with new syphilis infections. Aids. 2004;18:2075–2079. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200410210-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien K, Nixon S, Glazier RH, Tynan AM. Progressive resistive exercise interventions for adults living with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004. p. CD004248. [DOI] [PubMed]