Abstract

Triassic tetrapods are of key importance in understanding their evolutionary history, because several tetrapod clades, including most of their modern lineages, first appeared or experienced their initial evolutionary radiation during this Period. In order to test previous palaeobiogeographical hypotheses of Triassic tetrapod faunas, tree reconciliation analyses (TRA) were performed with the aim of recovering biogeographical patterns based on phylogenetic signals provided by a composite tree of Middle and Late Triassic tetrapods. The TRA found significant evidence for the presence of different palaeobiogeographical patterns during the analysed time spans. First, a Pangaean distribution is observed during the Middle Triassic, in which several cosmopolitan tetrapod groups are found. During the early Late Triassic a strongly palaeolatitudinally influenced pattern is recovered, with some tetrapod lineages restricted to palaeolatitudinal belts. During the latest Triassic, Gondwanan territories were more closely related to each other than to Laurasian ones, with a distinct tetrapod fauna at low palaeolatitudes. Finally, more than 75 per cent of the cladogenetic events recorded in the tetrapod phylogeny occurred as sympatric splits or within-area vicariance, indicating that evolutionary processes at the regional level were the main drivers in the radiation of Middle and Late Triassic tetrapods and the early evolution of several modern tetrapod lineages.

Keywords: Tetrapoda, Triassic, palaeobiogeography, TRA, evolution

1. Introduction

The Triassic Period (251–201.6 Myr ago; Walker & Geissman 2009) was a key time span in the evolutionary history of tetrapods, which encompassed the origin of a variety of new clades (e.g. parasuchians, rauisuchians, aetosaurs, pterosaurs), as well as the early radiation of many extant lineages (e.g. lissamphibians, testudinates, squamates, mammaliamorphs, crocodylomorphs, dinosaurs; Bonaparte 1982; Benton 1983; Colbert 1984; Gaffney 1986; Bonaparte et al. 2003; Evans 2003; Brusatte et al. 2008; Marjanovic & Laurin 2008). During the Permian, the continental tetrapod faunas were dominated by basal synapsids, but after the Permo-Triassic extinction event eucynodontians and archosauromorphs assumed a major role in terrestrial vertebrate communities (Bakker 1977; Bonaparte 1982; Benton 1983; Colbert 1984). This faunal replacement culminated with the numerical abundance of dinosaurs in latest Triassic times, a dominance almost unchallenged during the following 135 Myr.

All modern continents coalesced into the supercontinent of Pangaea during the Triassic, with few physical barriers for biotic dispersal among terrestrial tetrapods (Shubin & Sues 1991; Blakey 2006; Golonka 2007), a unique palaeogeographical pattern during the evolutionary history of the group. Initial palaeobiogeographical studies of Triassic tetrapods argued for a uniform and cosmopolitan fauna (Colbert 1973; Cracraft 1974), but more recent studies have begun to recognize provincialism and palaeolatitudinal variation in their distribution (Tucker & Benton 1982; Benton 1983; Shubin & Sues 1991; Ezcurra 2006; Irmis et al. 2007; Nesbitt et al. 2007). The latter is in accordance with palaeolatitudinal distinction between the macrofloras of Laurasia (North America, Europe, Asia) and Gondwana (South America, Africa, Antarctica, Madagascar, India, Australia), with a dominance of cyacodophytes, conifers and bennettitaleans in the north and a corystospermacean-dominated Dicroidium-flora in the south (Meyen 1987; Dobruskina 1993).

A historical cladistic biogeographical study based on a ‘tree reconciliation analysis’ (TRA) of Tetrapoda has been performed here in order to unveil the relationships between the main Middle and Late Triassic tetrapod-bearing assemblages based on vicariant biogeographical signals. A wealth of novel phylogenetic information for most of the Triassic tetrapod groups has come to light in recent years, and a quantitative analysis that incorporates this avalanche of new data will provide a test of previous hypotheses of biogeographical provincialisms and palaeolatitudinal distinctions among the tetrapod faunas of this time span (Page 1988, 1990, 1993, 1994a,b; Page & Charleston 1998; Hunn & Upchurch 2001). The reconstruction of the geographical area relationships and reconciliation analyses based on tetrapod phylogenies can provide new information of the evolution of the clades which appeared during the Triassic, including the early radiation of modern tetrapod lineages.

2. Material and methods

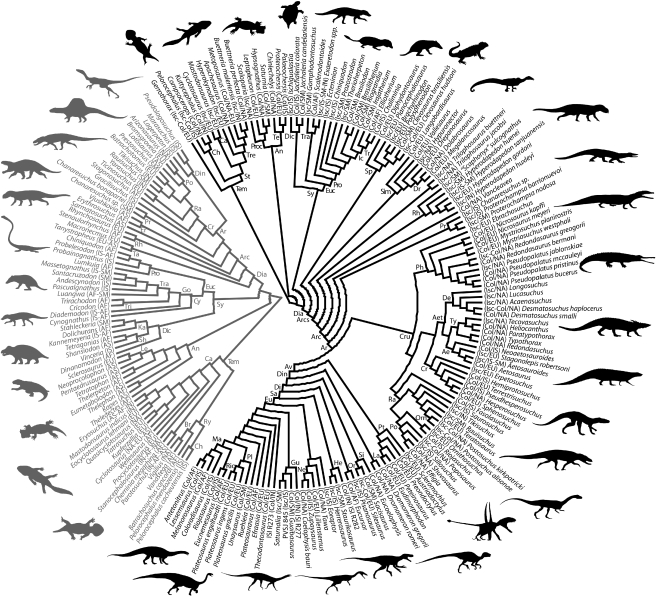

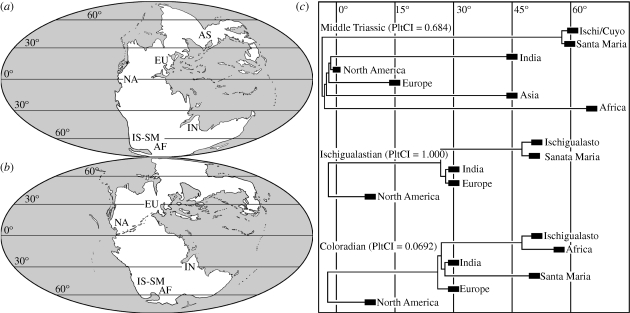

In order to perform the TRA (see Page 1988, 1994a; Hunn & Upchurch 2001; Upchurch et al. 2002, among others, for a detailed discussion of the method), a composite tree comprised of 209 Middle and Late Triassic tetrapod taxa was constructed by combining the topologies of several cladistic analyses (see the electronic supplementary material, S2; figure 1). The search of the optimal area cladograms (OACs) was conducted in Component 2.0 (Page 1993; see the electronic supplementary material, S5) and the time-slicing protocol described by Upchurch et al. (2002) was employed for three time frames: Middle Triassic, Ischigualastian (early Late Triassic) and Coloradian (late Late Triassic; see the electronic supplementary material, S3). Seven geographical areas were considered in the analyses—western Argentina (Ischigualasto-Villa Unión/Cuyo Basins), southern Brazil (Santa Maria Supersequence), meridional Africa, Asia, Europe and North America—but Asia and Africa were not included among the Late Triassic and Ischigualastian assemblages, respectively, because of the low number of tetrapods included in numerical phylogenetic analyses known from these areas.

Figure 1.

Composite trees of Middle (grey) and Late Triassic (black) tetrapods employed in the TRA analyses. The geographical procedence and reptile age (Late Triassic) are detailed in each terminal. For abbreviations see the electronic supplementary material, S1.

Reconstructions of biogeographical events and randomization tests, which determines the probability that the observed biogeographical pattern could have occurred only by chance (Page 1994a, 1995), were conducted for each time slice in TreeMap 1.0 (Page 1995; see the electronic supplementary material, S6). In order to evaluate palaeolatitudinal patterns in the recovered OACs, the continuous character ‘palaeolatitude’ was optimized following a maximum parsimony criterion on these cladograms using TNT 1.1 (Goloboff et al. 2008) and a palaeolatitudinal consistency index (PltCI) was calculated. A stronger palaeolatitudinal signal in the reconstructed OAC is indicated as the PltCI is closer to 1, in which the strongest palaeolatitudinal signal is observed in a character without homoplasies (see Kluge & Farris 1969; see the electronic supplementary material, S8).

3. Results and discussion

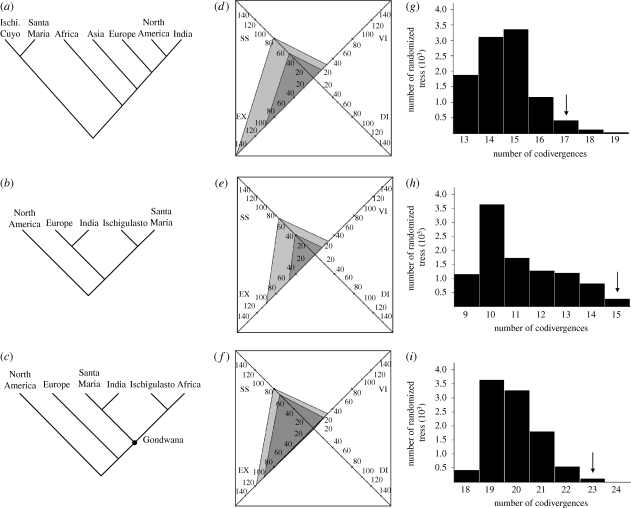

The TRAs of Middle and Late Triassic tetrapods recovered one OAC for each time slice, all of which are statistically significant judging by the randomization tests (p < 0.05; figure 2c,f,i,l and table 1), indicating that the biogeographical patterns of these time frames are highly unlikely to have occurred solely by chance.

Figure 2.

Recovered cladograms of optimized geographical areas (left), events reconstructed by the TRA (center) and histograms depicting the frequency of the randomized trees (right) for the (a) Middle Triassic, (b) Ischigualastian and (c) Coloradian time slices. In the events reconstructed by the TRA (center) the dark grey areas represent the actual number of recovered events and the light green areas the ratio of biogeographical/cladogenetic events multiplied by 100. The arrows in the histograms represent the number of codivergences recovered for this time slice. Abbreviations: DI, ‘dispersals’ (taxon shift, probably owing to sampling bias in the fossil record); EX, extinctions; Ischi, Ischigualasto; SS, sympatric splits; VI, vicariances.

Table 1.

Results of palaeobiogeographical analyses. (The recovered topology of the OACs are detailed in parenthetical notation for each time slice. SSf refers to the frequency of sympatric splitting events over the total of cladogenetic events present in the taxon cladogram. PltCI is the consistency index of the character ‘palaeolatitude’ optimized on the OACs.)

| time slice | optimal area cladogram topology | SSf | PltCI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Middle Triassic | ((IS,SM),(AF,(AS,(EU,(NA,IN))))) | 0.82 | 0.684 | 0.0419 |

| Ischigualastian | (NA,((IN,EU),(SM,IS))) | 0.76 | 1.000 | 0.0266 |

| Coloradian | (NA,(EU,((IN,SM),(AF,IS)))) | 0.80 | 0.692 | 0.0123 |

(a). Middle Triassic tetrapod palaeobiogeography

The TRA of the Middle Triassic time slice found an OAC which does not recover a palaeobiogeographical distinction between Gondwanan and Laurasian territories (figure 2a). In this regard, India was found as the sister-area of North America and Africa as closer to India and northern landmasses (Asia, Europe, North America) than to other Gondwanan assemblages (i.e. Ischigualasto-Cuyo and Santa Maria areas). No clear palaeolatitudinal signal is observed (PltCI = 0.684, see table 1), resembling the results of Shubin & Sues (1991; figure 3). The grouping composed of India and northern landmasses seems to be characterized by tanystropheid archosauromorphs and leptopleuronin procolophonids. By contrast, several tetrapod clades are only present at high palaeolatitudes (i.e. Africa and South America), such as proterochampsid archosauriforms, probainognathian and cynognathian cynodonts, kannemeyerioid dicynodonts and chigutisaurid temnospondyls.

Figure 3.

Palaeogeographical reconstructions of the (a) Middle Triassic and (b) Late Triassic indicating the geographical areas analysed here. (c) OACs calibrated to the palaeolatitude ((a,b) redrawn from Blakey 2006) and PltCIs. Abbreviations as in figure 2.

The recovery of a polyphyletic ‘Gondwana’ suggests that no efficient climatic or geographical barrier for the southern–northern interchange of continental tetrapods was present during this time span, as previously indicated by Shubin & Sues (1991). The latter is supported by the presence of several clades depicting a cosmopolitan distribution during the Middle Triassic, such as rauisuchian crurotarsans, erythrosuchid archosauriforms, rhynchosaur archosauromorphs, shansiodontid dicynodonts, procolophonid parareptiles and capitosauroid temnospondyls (figure 1). Accordingly, although a fully cosmopolitan distribution for terrestrial tetrapods was not recovered for the Middle Triassic, contrasting with Shubin & Sues (1991), the OAC suggests a Pangaean distribution (allowing southern–northern biotic interchange) with poor palaeolatitudinal distinctions for terrestrial tetrapods during this time. This is a robust signal, because despite a probable poor sampling we can recognize widespread groups, and greater sampling will probably confirm that other groups were cosmopolitan as well.

(b). Ischigualastian Late Triassic tetrapod palaeobiogeography

The Ischigualastian OAC does not find a distinction between Gondwanan and Laurasian territories, with the grouping of Europe and India as the sister clade of South American assemblages (figure 2d). However, the OAC exhibits a clear palaeolatitudinal grouping (PltCI = 1.000), with territories situated at roughly the same palaeolatitude found as sister areas: Santa Maria + Ischigualasto (approx. 45°) and India + Europe (approx. 30°; sensu Scotese 2001; Blakey 2006; figure 3 and table 1). North America, which was situated at a low palaeolatitude during the early Late Triassic (approx. 10°; Blakey 2006), is found as the sister area of all the other assemblages. This palaeobiogeographical pattern is based on the presence of tetrapod faunas with conspicuous palaeolatitudinal distinctions during Ischigualastian times. In this regard, a tetrapod fauna of high palaeolatitudes (approx. 45°; Ischigualasto and Santa Maria) can be characterized by the presence of guaibasaurid and herrerasaurid dinosaurs, the aetosaur Aetosauroides, proterochampsid archosauriforms, basal species of the rhynchosaur genus Hyperodapedon and probainognathian cynodonts. A fauna of middle palaeolatitudes (30°; India and Europe) seems to be distinguished by the presence of the Hyperodapedon gordoni + Hyperodapedon huxleyi clade of rhynchosaurs and stereospondyl temnospondyls. The Ischigualastian North American assemblages are mainly characterized by desmatosuchine aetosaurs and trilophosaurid archosauromorphs, clades which seem to be restricted to low palaeolatitudes (approx. 10°). Finally, the tetrapod faunas of high and middle palaeolatitudes (i.e. South America, India and Europe) share a group of clades absent at lower palaeolatitudes (southern and central North America), such as aetosaurine aetosaurs, rhynchosaur archosauromorphs and traversodontid cynodonts. Similar strong palaeolatitudinal provincialisms were also found for Triassic floras, which seem to be essentially related to latitudinal climatic distinctions (Artabe et al. 2003).

The grouping of two geographically distant areas, such as the northern assemblages of Europe (approx. 30° N) and the southern ones of India (approx. 30° S), may suggest that some kind of southern–northern biotic interchange would have been possible during the Ischigualastian (figure 3), supported, for example, by the sister–taxon relationship of the European Hyperodapedon gordoni and the Indian Hyperodapedon huxleyi (Langer & Schultz 2000; figure 1). However, this palaeobiogeographical signal could not only be explained by dispersal between these southern and northern areas. It must be noted that the clades which characterize the Ischigualastian tetrapod faunas of middle palaeolatitudes (i.e. India and Europe) exhibited a worldwide cosmopolitan distribution during the Middle Triassic (e.g. rhynchosaurs and stereospondyls). Accordingly, the palaeolatitudinal distinctions observed in the Ischigualastian faunas could also be the result of vicariant events and/or local extinctions after the appearance of probable climatic barriers (Artabe et al. 2003) for tetrapod dispersal during the early Late Triassic.

(c). Coloradian Late Triassic tetrapod palaeobiogeography

The recovered OAC for the Coloradian time slice found a monophyletic Gondwanan clade composed of the Santa Maria + India and the South Africa + Ischigualasto clusters (figure 2g; PltCI = 0.692). Europe was recovered closer to Gondwana than to North America, supported by tetrapod clades shared by these territories such as sauropodomorphs and aetosaurines (figure 1). The common presence of massopodan sauropodomorphs and tritheledontid cynodonts are of strong support for the close palaeobiogeographical affinities between Ischigualasto and South Africa. The absence of upper Coloradian tetrapod-bearing beds in the Santa Maria Supersequence (Langer et al. 2007) and poor sampling of the Indian Coloradian (Bandyopadhyay & Sengupta 2006) suggests that the grouping of these two assemblages, which do not share any unique monophyletic tetrapod clade at this time slice, should be treated with caution.

The results from this time slice suggest that Gondwanan tetrapod assemblages were palaeobiogeographically closer to each other than to northern territories, but biotic connections were still strong between them. In this regard, several tetrapod clades exhibit a wide palaeolatitudinal distribution, ranging from ‘Laurasian’ to Gondwanan assemblages (e.g. non-guaibasaurid sauropodomorphs, coelophysoids, silesaurids, phytosaurs: Chatterjee 1978; Kischlat & Lucas 2003; crocodylomorphs, sphenodontians, procolophonids, testudinates), suggesting the absence of an effective barrier preventing a southern–northern tetrapod interchange during the Coloradian. North American assemblages present some faunal peculiarities during the Coloradian, such as the presence of lagerpetids, typothoracisines, desmatosuchines and phytosaurs of the genera Pseudopalatus and Redondasaurus, and the absence of sauropodomorphs and chigutisaurids (figure 1). The latter suggests the presence of a fauna of low palaeolatidudes during the latest Triassic.

(d). Implications for Triassic tetrapod evolution and early radiation of modern lineages

The results obtained from the TRA performed here have implications for the early macroevolutionary history of Tetrapoda. The presence of a roughly Pangaean Middle Triassic tetrapod palaeobiogeographical pattern suggests that lineages which appear for the first time in rocks of this age or earlier, such as rauisuchian crurotarsans, would have achieved an early cosmopolitan distribution, a plausible explanation for the widespread presence of members of this group in southern and northern territories during the Ischigualastian (e.g. rauisuchids, poposaurids; figure 1) despite the presence of a strong palaeolatitudinal faunal distinction during this later time. In addition, tetrapod groups unrepresented in Middle Triassic beds also exhibit a cosmopolitan distribution during the Late Triassic (e.g. aetosaurs, phytosaurs: Chatterjee 1978; sphenodontians; figure 1), but ghost lineages suggest their minimum time of divergence during the Middle Triassic or earlier (Sereno 1991; Evans 2003; Brusatte et al. 2010), providing a possible explanation for their first appearance in the fossil record as a geographically widely distributed group. Several other tetrapod clades which appeared in the fossil record during the early Late Triassic are restricted to palaeolatitudinal belts, including dinosaurs and probainognathians at high latitudes (Ischigualasto, Santa Maria and Lower Maleri formations), and pseduopalatine phytosaurs and pterosaurs at medium and low latitudes (North American and European Triassic depocentres). The latter would explain, for example, the absence of dinosaurs in Europe and North America during a time span of at least 10 Myr (Hunt et al. 1998; Irmis & Mundil 2008) after they first appeared in Gondwanan assemblages 230 Myr ago (Furin et al. 2006).

Regarding the evolutionary processes that shaped Middle and Late Triassic tetrapod clades, the analyses performed here found that more than 75 per cent of the cladogenetic events documented in the phylogeny of Tetrapoda (figure 1) occurred as sympatric splits, understood as true sympatry or within-area vicariance, for the coarse geographical areas considered here (table 1: SSf, figure 2b,e,h,k: SS light grey area). The strong influence of sympatric cladogenetic events can be observed in the evolutionary history of several Middle and Late Triassic tetrapod lineages (figure 1). Although the palaeogeographical realities of the Middle and Late Triassic seem to have allowed biotic interchanges between distant areas, the number of cladogenetic events resulting in daughter lineages spanning different areas is not very common. Accordingly, these results indicate that sympatric splitting events were the main driver of the radiation of Middle and Late Triassic tetrapods and the early evolution of several modern tetrapod lineages.

Acknowledgements

I thank F. Agnolín, R. Butler, S. Brusatte, A. Martinelli, J. Desojo, A. Lecuona, the associate editor X. Xu and two anonymous reviewers for their comments on this manuscript. Access to the free version of TNT 1.1 was possible owing to the Willi Henning Society.

References

- Artabe A. E., Morel E. M., Spalletti L. A.2003Caracterización de las provincias fitogeográficas triásicas de Gondwana extratropical. Ameghiniana 40, 387–405 [Google Scholar]

- Bakker R. T.1977Tetrapod mass extinctions: a model of the regulation of speciation rates and immigration by cycles of topographic diversity. In Patterns of evolution as illustrated by the fossil record (ed. Hallan A.), pp. 439–468 New York, NY: Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay S., Sengupta D. P.2006Vertebrate faunal turnover during the Triassic-Jurassic transition: an Indian scenario. In The Triassic–Jurassic terrestrial transition (eds Harris, et al.), pp. 77–85 New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 37 [Google Scholar]

- Benton M. J.1983Dinosaur success in the Triassic: a noncompetitive ecological model. Q. Rev. Biol. 58, 29–55 (doi:10.1086/413056) [Google Scholar]

- Blakey R. Mollweide plate tectonic maps. 2006. http://jan.ucc.nau.edu/~rcb7/mollglobe.html . [Google Scholar]

- Bonaparte J. F.1982Faunal replacement in the Triassic of South America. JVP 2, 362–371 [Google Scholar]

- Bonaparte J. F., Martinelli A. G., Schultz C. L., Rubert R.2003The sister group of mammals: small cynodonts from the Late Triassic of southern Brazil. Rev. Brasil. Paleontol. 5, 5–27 [Google Scholar]

- Brusatte S. L., Benton M. J., Ruta M., Lloyd G. T.2008Superiority, competition, and opportunism in the evolutionary radiation of dinosaurs. Science 321, 1485–1488 (doi:10.1126/science.1161833) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusatte S. L., Benton M. J., Desojo J. B., Langer M. C.2010The higher-level phylogeny of Archosauria (Tetrapoda: Diapsida). J. Syst. Palaeontol. 8, 3–47 [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S.1978A primitive parasuchid (phytosaur) reptile from the Upper Triassic Maleri Formation of India. Palaeontology 21, 83–127 [Google Scholar]

- Colbert E. H.1973Continental drift and the distributions of fossil reptiles. In Implications of continental drift for the Earth sciences (eds Tailing D. H., Runcorn S. K.), pp. 395–412 London, UK: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Colbert E. H.1984Mesozoic reptiles, India and Gondwanaland. Ind. J. Earth Sci. 11, 25–37 [Google Scholar]

- Cracraft J.1974Continental drift and vertebrate distribution. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 5, 215–261 (doi:10.1146/annurev.es.05.110174.001243) [Google Scholar]

- Dobruskina I.1993Relationships of floral and faunal evolution during the transition from the Paleozoic to the Mesozoic. In The nonmarine Triassic (eds Lucas S. G., Morales M.), pp. 107–112 New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 3 [Google Scholar]

- Evans S. E.2003At the feet of the dinosaurs: the early history and radiation of lizards. Biol. Rev. 78, 513–551 (doi:10.1017/S1464793103006134) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezcurra M. D.2006The evolutionary explosion of the Norian neotheropods and sauropodomorphs (Upper Triassic) Academia Nacional de Ciencias, Resúmenes, p. 82 [Google Scholar]

- Furin S., Preto N., Rigo M., Roghi G., Gianolla P., Crowley J. L., Bowring S. A.2006High-precision U–Pb zircon age from the Triassic of Italy: implications for the Triassic time scale and the Carnian origin of calcareous nannoplankton and dinosaurs. Geology 34, 1009–1012 (doi:10.1130/G22967A.1) [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney E. S.1986Triassic and early Jurassic turtles. In The beginning of the age of dinosaurs: faunal changes across the Triassic–Jurassic boundary (ed. Padian K.), pp. 183–187 Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Goloboff P. A., Farris J. S., Nixon K.2008TNT, a free program for phylogenetic analysis. Cladistics 24, 774–786 (doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2008.00217.x) [Google Scholar]

- Golonka J.2007Late Triassic and Early Jurassic palaeogeography of the world. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 244, 297–307 [Google Scholar]

- Hunn C. A., Upchurch P.2001The importance of time/space in diagnosing the causality of phylogenetic events: towards a ‘chronobiogeographical’ paradigm? Syst. Biol. 50, 1–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt A. P., Lucas S. G., Heckert A. B., Sullivan R. M., Lockley M. G.1998Late Triassic dinosaurs from the western United States. Geobios 31, 511–531 (doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(98)80123-X) [Google Scholar]

- Irmis R. B., Mundil R.2008New age constraints from the Chinle Formation revise global comparisons of Late Triassic vertebrate assemblages. J. Vert. Paleontol. 28, 95A [Google Scholar]

- Irmis R. B., Nesbitt S. J., Padian K., Smith N. D., Turner A. H., Woody D., Downs A.2007A Late Triassic dinosauromorph assemblage from New Mexico and the rise of dinosaurs. Science 317, 358–361 (doi:10.1126/science.1143325) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kischlat E.-E., Lucas S. G.2003A phytosaur from the Upper Triassic of Brazil. J. Vert. Paleontol. 23, 464–467 [Google Scholar]

- Kluge A. G., Farris J. S.1969Quantitative phyletics and the evolution of anurans. Syst. Zool 18, 1–32 (doi:10.2307/2412407) [Google Scholar]

- Langer M. C., Schultz C. L.2000A new species of the Late Triassic rhynchosaur Hyperodapedon from the Santa Maria Formation of south Brazil. Palaeontology 43, 633–652 (doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00143) [Google Scholar]

- Langer M. C., Ribeiro A. M., Schultz C. L., Ferigolo J.2007The continental tetrapod–bearing Triassic of South Brazil. In The Global Triassic (eds Lucas S. G., Spielmann J. A.), pp. 201–218 New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science Bulletin 41 [Google Scholar]

- Marjanovic D., Laurin M.2008Assessing confidence intervals for stratigraphic ranges of higher taxa: the case of Lissamphibia. Acta Palaeontol. Pol. 53, 413–432 (doi:10.4202/app.2008.0305) [Google Scholar]

- Meyen S. V.1987Fundamentals of palaeobotany London, UK: Chapman and Hall [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt S. J., Irmis R. B., Parker W. G.2007A critical reevaluation of the Late Triassic dinosaur taxa of North America. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 5, 209–243 (doi:10.1017/S1477201907002040) [Google Scholar]

- Page R. D. M.1988Quantitative cladistic biogeography: constructing and comparing area cladograms. Syst. Zool. 37, 254–270 (doi:10.2307/2992372) [Google Scholar]

- Page R. D. M.1990Temporal congruence and cladistic analysis of biogeography and cospeciation. Syst. Zool. 39, 205–226 (doi:10.2307/2992182) [Google Scholar]

- Page R. D. M.1993Genes, organisms, and areas: the problem of multiple lineages. Syst. Biol. 42, 77–84 [Google Scholar]

- Page R. D. M.1994aMaps between trees and cladistic analysis of historical associations among genes, organisms, and areas. Syst. Biol. 43, 58–77 [Google Scholar]

- Page R. D. M.1994bParallel phylogenies: reconstructing the history of host–parasite assemblages. Cladistics 10, 155–173 (doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1994.tb00170.x) [Google Scholar]

- Page R. D. M. TreeMap for Windows, v. 1.0a. 1995. See http://taxonomy.zoology.gla.ac.uk/rod/treemap.html . [Google Scholar]

- Page R. D. M., Charleston M. A.1998Trees within trees: phylogeny and historical associations. Trends Ecol. Evol. 13, 356–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotese C. R.2001Atlas of earth history, PALEOMAP Project, Arlington, TX. See http://scotese.comhttp://scotese.com [Google Scholar]

- Sereno P. C.1991Basal archosaurs: phylogenetic relationships and functional implications. Mem. Soc. Vert. Paleontol. 2, 1–53 (doi:10.2307/3889336) [Google Scholar]

- Shubin N. H., Sues D.1991Biogeography of early Mesozoic continental tetrapods: patterns and implications. Paleobiology 17, 214–230 [Google Scholar]

- Tucker M. E., Benton M. J.1982Triassic environments, climates and reptile evolution. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 40, 361–379 [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch P., Hunn C. A., Norman D. B.2002An analysis of dinosaurian biogeography: evidence for the existence of vicariance and dispersal patterns caused by geological events. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 613–621 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1921) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J. D., Geissman J. W.compilers2009Geologic Time Scale Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America [Google Scholar]