Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Early first drinking (EFD) experiences predict later alcohol problems. However, the longitudinal pathway from early childhood leading to EFD has not been well delineated. Based on documented links between drinking behaviors and chronic antisocial behaviors, this paper tests a common diathesis model in which precursive patterns of aggression and delinquent behavior – from preschool onward – anticipate EFD.

METHOD

Participants were 220 male children and their parents in a high-risk for substance-use-disorder prospective study. EFD was defined as having had a first drink by 12–14 years of age. Stacked structural equation models and configural frequency analyses were used to compare those with and without EFD on aggression and delinquent behavior from ages 3–5 through 12–14.

RESULTS

Delinquent behavior and aggression decreased normatively throughout childhood for those with and without EFD, although those with EFD showed precocious resurgences moving into early adolescence. EFD was associated with delinquent behavior more than aggression. Early drinkers were more delinquent at most ages – with a direct effect of preschool predisposition on adolescent behavior only within the EFD group. EFD was disproportionately likely among individuals with high levels of delinquent behavior at both 3–5 and 12–14 years of age, but uncommon among individuals with low levels of delinquent behavior during those two age periods.

CONCLUSIONS

EFD and delinquent behavior share a common diathesis evident prior to school entry. Intervention and prevention programs targeting problem drinking risk should focus on dismantling this emergent, primarily delinquency-related developmental trajectory.

Keywords: substance use, drinking onset, antisocial behavior, child development, continuity

Introduction

A substantial literature has demonstrated that heightened risk for alcohol problems and later alcohol use disorder (AUD) is associated with having had an early first drinking (EFD) experience.1–7 Given the evidence that very early child behavior problems also predict adult substance use disorder, as revealed by research showing a pervasively antisocial alcoholic subtype,8–11 one important clinical question is: What happens during the intervening period between early childhood and that first drink?

Considerable circumstantial evidence suggests that a continuity risk-aggregation model describes this process, at least for a subset of troubled children.11–14 According to this continuity paradigm, the etiology for EFD begins well before drinking onset.11–12 Risky characteristics and risky environments from infancy onward funnel the individual into a pathway of risk aggregation and cumulative disadvantage – leading to a greater likelihood for early onset of alcohol and other drug use, delinquency, and depression in adolescence as well as substance abuse and other psychopathology throughout the adult years.13 This paper adds to the extant literature which has often focused on static risk factors by testing a developmental model for EFD that links alcoholic outcomes to early antisocial behaviors, recognizes the possibility of change as a counterpoint to stability in behavior problems over time, and uses data from multiple age periods to more fully map the cascade of risk from preschool through early adolescence.

A Review of the Literature on EFD and Antisocial Behaviors

National epidemiological data indicate that median age of first drink is 14,15 with only one-quarter of high school students trying more than just a few sips before age 13.16 Alcohol-related difficulties in adulthood as well as other disinhibitory behaviors (e.g., smoking, other drug use, injuries, violence, drunk driving, and absenteeism from school or work) tend to vary inversely with EFD.1–7 However, despite the proliferation of studies on the sequelae to EFD, only a few researchers have examined antecedents to EFD – with conduct problems, alcohol-dependent siblings, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), parental psychopathology, and divorce identified as predictors.3, 17–18

Conduct problems fit particularly well within a larger theoretically coherent model of ongoing development. Specifically, it is likely that antisocial behaviors and EFD stem from a common diathesis. Multiple indicators of deviance (e.g., delinquency, substance use, smoking, sexual activity, school failure) co-vary in adolescence and are so interrelated as to comprise a conduct problem syndrome.19 There are also likely to be etiological connections between these problems.20 Similar findings have been reported in the alcoholism literature, where a syndrome of problem behavior propensities has been regarded as central to one subtype of the disorder. Even antisocial behavior and EFD have been characterized as symptoms of the same underlying genetic vulnerability.3–4, 8–11

If the linkage between multiple problem behaviors lies at the core of an antisocial pathway into the earliest manifestations of alcohol involvement, EFD, then very early phenotypic manifestations of risk should be evident – and presumably, should continue to unfold throughout childhood. However, evidence for the pathway from childhood antisocial behaviors to adult AUD has either been retrospective or lacking in observations over enough developmental periods to establish its continuity (and various age-graded phenotypic manifestations).

In contrast, when considering the antisociality pathway – without attention to the substance abusing component – there is robust support for phenotypic continuity over the life course in conduct problems or conduct disorder/antisocial personality disorder,21–23 delinquency/crime,24–27 and aggression.28–32 This literature has demonstrated that the most chronic and severe delinquents show persistent and pervasive patterns of antisocial behavior with onset of delinquency occurring before adolescence.33 Similarly, early aggression tends to be the best predictor of later aggression with a degree of stability not much lower than that found for IQ.34

Although many researchers have examined aggregated antisocial or externalizing behavior problems, a growing literature has shown the advantages of looking at aggressive and delinquent dimensions separately. These are highly co-morbid (and genetically correlated)35 but distinguishable constructs: Studies have yielded empirically distinct syndrome scales derived from factor analysis,36 shown different correlates and predictors,37 produced different estimates for heritability as well as different degrees of shared environmental influence with twins,38–39 and revealed different developmental trajectories – with aggression decreasing and delinquent behavior increasing into adolescence.40–41

Aggression conceptually involves under-control, lack of social skill or subtlety, conflict with others, and use of violence or forceful threats. Delinquent behavior is more explicitly connected to rule-breaking; characterized by activities that are sneaky, deceitful, and even clandestine – rather than the interpersonally annoying, demanding, coercive, sometimes physical, and direct confrontations of aggression.42 In adolescence the activity is demonstrably delinquent; in childhood, particularly during the earliest years, it involves rule breaking (i.e., involving transgression against a higher authority) which in this age period is frequently more obvious than clandestine.

The Current Study

Our study seeks to advance research on EFD, as a proxy for early problem alcohol use, and its relationship to continuity in antisocial behavior. Several weaknesses in the extant literature are addressed.

First, research explicitly on EFD has primarily focused on downstream sequelae (e.g., drunkenness or alcoholic diagnosis) rather than precursors to drinking onset. Studies on antecedents are few, but have consistently implicated disinhibitory conduct problems.3, 17–18 Should early markers of these characteristics be identified, this would permit identification of at-risk individuals well before drinking habits become ingrained.

Second, although continuity in antisocial behavior has been connected to greater risk for alcohol-related outcomes, prior studies have first observed this connection during middle childhood, with no developmental assessment at earlier intervals. To completely map the pathway, it is essential to look at behavioral difficulties in very young children and connect them to later behavior problems as well as drinking onset.

Third, prior work has focused on continuity with less attention accorded to discontinuity. The critical developmental and clinical question is whether it is only persistent problems from early childhood onward that predict risk for early alcohol abuse (as marked by EFD) – or whether EFD is also likely among those with escalating, later childhood/early adolescent onset difficulties that end up high by the cusp of adolescence.

Fourth, although aggregated behavioral difficulties have been connected to both EFD and later alcoholism, less attention has been given to differentiating between childhood aggression and childhood delinquency/rule breaking in the etiologic pathway leading to problem alcohol use.

Here we focus on behavioral difficulties upstream from serious alcohol-specific outcomes, beginning with preschool. The current study proposes that early drinking is but one marker on the trajectory followed by children who demonstrate persistent antisocial behavior problems (i.e., those that are ongoing, spanning multiple developmental periods starting at an early age) in contrast to remitting or late onset behavior problems. Moreover, it recognizes that antisocial behavior is multi-faceted and looks to determine whether EFD risk can be traced to more specific behavioral substrates.

Our first hypothesis is that early onset drinkers follow a developmental trajectory marked by high levels of antisocial behavior from preschool predispositions onward. A second hypothesis is that both distal (preschool) and proximal (adolescent) antisocial problems are distinguishing characteristics along the pathway leading to and through drinking onset. A third hypothesis is that aggression and delinquent behavior from these two developmental periods can parsimoniously categorize individuals into groups that differ in likelihood of EFD. A subsidiary prediction is that different prediction patterns will be found for aggression versus delinquent behavior.

Method

Participants

Participants were 220 male adolescents and their parents from the prospective Michigan Longitudinal Study (MLS).43 This ongoing project utilized population-based recruitment strategies to identify alcoholic and ecologically-matched, biological, intact families (see ref 43 for a full description of study design). Alcoholic families were identified on the basis of father’s drinking status. The sample, therefore, is one selected for high risk of AUD; 70% of families had fathers who met DSM-IV criteria for lifetime AUD at recruitment and 56% met criteria for a current diagnosis in the three preceding years. Child and both parents were assessed extensively in their home following recruitment (Wave 1, child age 3–5), with assessments repeated every 3 years. The data used here were collected at recruitment and when children were approximately 6–8 (Wave 2), 9–11 (Wave 3), and 12–14 (Wave 4) years of age.

For inclusion in the current sample, there were two criteria. The first was the availability of behavior problem ratings at Waves 1 and 4 and drinking data at Wave 4, so as to avoid missing data imputation on these key dependent variables. Second, families must have participated in at least one middle childhood wave.

Screening for differences between the study sample and those dropped due to insufficient data (n = 113) revealed some bias. Dropped cases had fathers who were higher in AUD (χ2 (2, 333) = 8.93, p = .012) and more antisocial (χ2 (1, 322) = 15.24, p < .001) as well as mothers who were more depressed (χ2 (3, 328) = 8.15, p = .043) and children who were more aggressive at Wave 4 (t(248) = 2.20, p = .029). No significant differences were found for maternal AUD, maternal antisocial personality disorder, paternal depression, Wave 4 delinquent behavior, or Wave 1 aggression and delinquent behavior. Overall, the study sample is slightly more normative than the larger MLS full sample, and therefore is less skewed toward psychopathology (i.e., more comparable to general population samples).

The proportion of missing values on scores for the aggression and delinquent behavior subscales in the study sample was 17% at Wave 2 and 5% at Wave 3. Missing values were imputed in a larger dataset comprised of forty-two variables using the expectation maximization algorithm in SYSTAT. Little’s MCAR test yielded a chi-square of 1122.22 (df=1078, p = .17) showing that no identifiable pattern existed to the missing data within the sample of 220 cases.44

Procedure

Data were collected by trained project staff masked to family alcoholism status. At each wave, the visits involved approximately 15 hours of contact time for each parent and seven hours of time for the target child. Contacts included questionnaire sessions, semi-structured interviews, and interactive tasks. Families were compensated for their participation. IRB approval was secured, and consent forms were signed by participants prior to data collection.

Child Measures

First Drink

EFD was measured by questionnaire at Wave 4. Adolescents were asked at what age they first tried alcohol excluding just a “sip” from an adult. In total, 25% of the sample (n = 55) reported having a first drink by 12–14 years of age and were designated as early first drinkers or EFD, whereas 75% did not (n = 165) (nonEFD).

Antisocial Behavior

Child antisocial behavior was measured by maternal ratings on the aggressive and delinquent behavior symptom subscales of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) at each wave.36, 45 One item (alcohol and other drug use) was omitted from the delinquent behavior subscale to prevent artificial inflation of the correlation with drinking onset status. Items were rated on a three-point scale and summed (with 20 aggression subscale items and 12 delinquent behavior subscale items). Higher scores reflect more severe behavior problems. Continuity versus discontinuity in aggression was operationalized by dichotomizing scores as “high” or “low” based on a mean splits at Wave 1 and Wave 4, yielding four cross-tabbed patterns of development: high-high, high-low, low-high, low-low (e.g., with those scoring above the mean at both waves classified as high-high and those scoring below the mean at both waves classified as low-low). Continuity versus discontinuity in delinquent behavior was operationalized the same way using delinquent behavior scores from Wave 1 and Wave 4. Group distributions are presented in Table 1. Although consistency was the stronger trend (55%), there was also considerable discrepancy in classifications between the two subscales.

Table 1.

Subgroup N’s Based on Aggression and Delinquent Behavior Scores Above or Below the Mean at Age 3–5 (Wave 1) and 12–14 (Wave 4)

| Delinquent Behavior Groups |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Low | Low-High | High-Low | High-High | Total N | |

| Aggression Groups | |||||

| Low-Low | 51 | 7 | 20 | 11 | 89 |

| Low-High | 6 | 11 | 1 | 9 | 27 |

| High-Low | 11 | 1 | 17 | 10 | 39 |

| High-High | 8 | 7 | 9 | 41 | 65 |

| Total N | 76 | 26 | 47 | 71 | 220 |

Note. Wave 1 Aggression M= 10.65 (0–27 range), Delinquent M = 1.88 (0–10 range); Wave 4 Aggression M= 7.06 (0–26 range), Delinquent M = 1.85 (0–12 range). Congruent cases (n=120) are highlighted and on the diagonal.

Data Analysis

To test Hypotheses 1 and 2, mean levels of antisocial behavior at each wave were compared between EFDs and nonEFDs and then autoregressive two-group (EFD, nonEFD) stacked structural equation models were run in LISREL 8.52, using maximum likelihood estimation. Configural frequency analysis (CFA)46 was used to test Hypothesis 3 that EFD is disproportionately associated with continuity at the high end and that avoidance of EFD is associated with continuity at the low end. With CFA, a cell with more cases than expected by chance is a “type;” a cell with fewer cases than expected by chance is an “antitype.” Lehmacher’s test (L)47 was used for significance testing with a Bonferroni-adjusted alpha level (α* = 0.05/8 cells = .00625). All analyses were run separately for aggression and delinquent behavior.

Results

Means and standard deviations for the two antisocial behavior subscales are presented in Table 2. T-tests showed differences by drinking onset group for Wave 4 aggression and for delinquent behavior at three time periods: Waves 1, 2, and 4. Early drinkers engaged in more delinquent activities at most time periods – with both more aggression and more delinquent behavior in the transition from late childhood to early adolescence.

Table 2.

Means (and Standard Deviations) by Drinking Onset Group for Aggression and Delinquent Behavior

| Variable | Wave | NonEFD | EFD | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Aggression | 1 | 10.47 (5.57) | 11.20 (5.51) | −0.85 |

| 2 | 8.61 (5.14) | 10.15 (5.40) | −1.90 | |

| 3 | 8.21 (5.69) | 8.31 (5.87) | −0.11 | |

| 4 | 6.58 (5.12) | 8.47 (5.96) | −2.27* | |

| Delinquent Behavior | 1 | 1.67 (1.28) | 2.53 (1.96) | −3.75** |

| 2 | 1.76 (1.32) | 2.96 (1.99) | −5.01*** | |

| 3 | 1.57 (1.43) | 1.99 (1.96) | −1.72 | |

| 4 | 1.45 (1.77) | 3.05 (2.70) | −5.00*** |

Note. Degrees of freedom were 218 for all tests. The same pattern of significance was found when equal variances were not assumed. EFD = Early First Drinking

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

To more precisely specify developmental differences in antisocial behavior between early drinkers and non-drinkers, stacked structural equation models were used to examine the influences of early antisocial behavior on later antisocial behavior. All parameters were first allowed to vary across drinking onset groups. When a tenable model was obtained, these parameters were constrained to be equal in an invariant model to test for group differences.

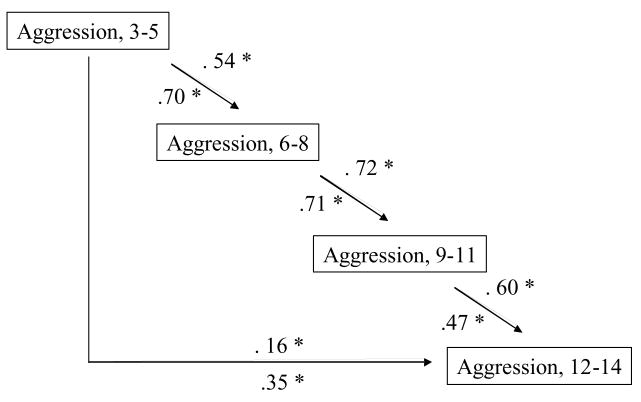

For aggression, the first model in which paths exist between each adjacent wave (without a path from Wave 1 to 4) produced a poor fit: χ2 = 16.41, df = 6, p = .01, RMSEA = .126, NFI = .96, CFI = .97. The path from Wave 1 to 4 aggression was then added, resulting in a model with acceptable fit statistics: χ2 = 3.79, df = 4, p = .43, RMSEA = .000, NFI = .99, CFI = 1.00. This specification was a significant improvement (Δχ2 = 12.62, Δdf = 2, p < .01). All paths were significant regardless of drinking onset status. Adding the remaining two pathways for a full model did not help (Δχ2 = 3.79, Δdf = 4, p > .05); paths from Wave 1 to Wave 3, and Wave 2 to Wave 4, aggression were non-significant for both groups.

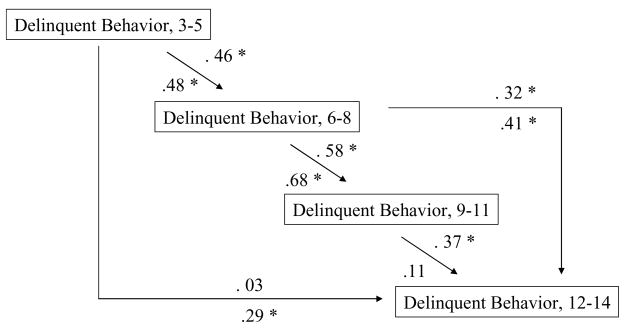

For delinquent behavior, the first model in which paths exist between each adjacent wave (again without the path from Wave 1 to 4) also provided a poor model fit: χ2 = 36.17, df = 6, p < .001, RMSEA = .215, NFI = .87, CFI = .89. The path from Wave 1 to 4 delinquent behavior was added, resulting in a model with significant improvement (Δχ2 = 11.36, Δdf = 2, p < .01), but additional changes were needed to meet acceptable fit criteria. Modification indices suggested a direct path between Wave 2 and Wave 4 delinquent behavior. A tenable model was achieved when this parameter was included (χ2 = 2.34, df = 2, p = .31, RMSEA = .039, NFI = .99, CFI = 1.00). It was also a significant improvement in fit with Δχ2 = 22.47, Δdf = 2, p < .01. (See Figure 1 for the common metric completely standardized solution for aggression and Figure 2 for the delinquent behavior solution. Parameter estimates for the nonEFD group are above each arrow; parameter estimates for the EFD group are below.) The path from Wave 1 to 4 delinquent behavior, reflecting the influence of early predisposition on adolescent outcomes, was significant for early drinkers only (whereas the path from Wave 3 to 4 delinquent behavior was significant for the nonEFD group only). Adding the remaining pathway for a full model did not further improve the fit (Δχ2 = 2.34, Δdf = 2, p > .05); the path from Wave 1 to Wave 3 delinquent behavior was non-significant for both groups.

Figure 1.

Common metric standardized solution for aggression by drinking onset group. Note. Parameter estimates are above arrows for the nonEFD group and below arrows for the EFD group; EFD = Early First Drinking

* p < .05.

Figure 2.

Common metric standardized solution for delinquent behavior by drinking onset group. Note. Parameter estimates are above arrows for the nonEFD group and below arrows for the EFD group; EFD = Early First Drinking

* p < .05.

Comparing each model to an invariance model (parameters between groups constrained to be equal) revealed differences in the covariance structure by first drink onset status for delinquent behavior but not aggression. For aggression, the invariance model yielded χ2 = 12.35, df = 12, p = .42, RMSEA = .016, NFI = .97, CFI = 1.00 which was not significantly different from the free parameter model, Δχ2 = 8.56, Δdf = 8, p > .05. For delinquent behavior, the invariance model yielded χ2 = 68.99, df = 11, p < .001, RMSEA = .220, NFI = .82, CFI = .85. The free parameter model for delinquent behavior showed significantly better fit: Δχ2 = 66.65, Δdf = 9, p < .01.

CFA was used to test whether antisocial problems in preschool and early adolescence could be used to parsimoniously categorize individuals into groups that differ in likelihood of early drinking onset. The CFA was not significant for aggression (Pearson’s χ2 = 6.31 for df = 3, p > .05), but was significant for delinquent behavior (Pearson’s χ2 = 18.38 for df = 3, p < .001) (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Configurations for Delinquent Behavior Group by First Drink Onset

| DO | Observed Frequency | Expected Frequency | L | Type/Antitype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 65 | 57.00 | 2.61* | Type |

| 12 | 11 | 19.00 | −2.61* | Antitype |

| 21 | 19 | 19.50 | −0.24 | -- |

| 22 | 7 | 6.50 | 0.24 | -- |

| 31 | 40 | 35.25 | 1.80 | -- |

| 32 | 7 | 11.75 | −1.80 | -- |

| 41 | 41 | 53.25 | −4.07* | Antitype |

| 42 | 30 | 17.75 | 4.07* | Type |

Note. D = delinquent behavior group; O = first drink onset. Numerals in DOcolumn represent ordered pairs of variable categories. Response categories for delinquent behavior were 1 = low-low, 2 = low-high, 3 = high-low, and 4 = high-high. For first drink onset, 1 = no onset and 2 = onset. L stands for Lehmacher’s (1981) test statistic; Bonferroni adjusted alpha, α* = .0062500 was used;

significant at α* = .0062500.

For delinquent behavior there were more cases than expected by chance for those low in delinquent behavior during both preschool and early adolescence who had not used alcohol by 12–14 years of age (i.e., the “11” type). There were fewer cases than expected by chance for low-low early drinkers (i.e., the “12” antitype). The opposite pattern was found for those who were high in delinquent behavior during both time periods, with more cases than expected by chance for the high-high group with drinking onset (i.e., the “42” type) and fewer cases than expected by chance for high-high children who had not yet tried alcohol (i.e., the “41” antitype).

Given the striking findings of a relationship between EFD and only delinquent behavior, additional post hoc analyses were conducted to identify the preschool CBCL delinquent behavior items most predictive of EFD. Significant Spearman’s rho correlations were found for hanging around with others who get into trouble (r=.221, p < .01), lying or cheating (r=.259, p < .01), setting fires (r=.204, p < .01), swearing (r=.168, p < .05), and thinking about sex too much (r=.161, p < .05).

Discussion

We examined the early first drinking experience from a perspective that emphasizes the developmental significance of early alcohol use as a marker in a pathway of problem behavior beginning in preschool. This perspective, looking at EFD as the outcome of an ongoing developmental trajectory characterized by antisociality, stands in contrast to studies focusing only on EFD as a precursor to alcoholism as well as a literature on drinking initiation that emphasizes concurrent or more proximate influences in the personal and social environment of adolescents.

Hypothesis 1, that early drinkers would have high levels of antisocial behavior from preschool predispositions onward, was only partially supported. Delinquent behavior and aggression decreased throughout childhood for those with and without EFD. However, those with EFD showed precocious resurgences moving into early adolescence. This resurgence was especially dramatic for delinquent behavior. That subsequent upturn is consistent with findings from other studies showing that delinquent behavior follows a curvilinear pattern of development from ages 4 to 18, initially declining, then increasing in early adolescence after about age 10.40–41 There was no subsequent increase seen for the non-drinkers. Thus, early drinkers were precocious in both their first use of alcohol and their delinquent involvements heading into adolescence. They were also more rule-breaking/delinquent than those in the nonEFD group at all ages but 9–11 but more aggressive only during the transition to early adolescence (ages 12–14). These divergent results reaffirmed the decision to look separately at aggression and delinquent behavior.

Structural equation models comparing early drinkers to those who had not yet tried alcohol by 12–14 years of age further supported the proposition of a delinquency-specific substrate within the EFD group. The direct effect of preschool delinquent behavior upon adolescent delinquent behavior was significant for early drinkers only. As described by Hypothesis 2, this direct path represents the influence of early predisposition on adolescent outcomes and demonstrates the etiologic contribution of precursive risk to later delinquent behavior among this subset of children. Note that one additional path was needed to obtain adequate model fit: a link between delinquent behavior in Waves 2 and 4. Although not hypothesized this path makes sense given that it bypasses the temporary convergence in ratings across the two groups at Wave 3; that EFD ratings dip at Wave 3 may also explain why the path from Wave 3 to Wave 4 was non-significant for this group.

Hypothesis 3 also received partial support; levels of delinquent behavior during preschool and early adolescence effectively differentiated between individuals with and without EFD. The same was not true for aggression.

Taken together, findings show that initial predispositions and the adolescent manifestations they predict, rather than a straight continuity model, best characterizes the relationship between delinquent behavior and EFD. They raise an important question as well: Why does a relationship with EFD exist for delinquent behavior but not aggression? This is not entirely unexpected given that previous research has shown that alcohol and drug use aligns more closely with delinquent behavior than with aggression in factor analysis.36 Also, conceptually there is a difference between aggression and delinquent behavior that may account for this developmental pattern, as well as the relationship with first alcohol use only for delinquent behavior. The difference is one of kind: Delinquent behavior is more “deviant.”

Aggression among preschool boys (boasting, arguing, showing off, and fighting) is to a degree expected, as the skills of emotion regulation and behavior regulation are mastered and as language is utilized to negotiate interpersonal relationships. Aggression then declines throughout childhood as communication becomes more proficient and socialization practices take effect. Delinquent behaviors (stealing, lying, vandalism, no guilt after misbehavior) more intrinsically connect to covert criminality and more severe rule-breaking – with increases into the teenage years seen as part of adolescent rebellion against authority and other ubiquitous developmental considerations even among those without a prior history of antisocial involvement.14

Future research is needed to differentiate the deeper origins of each antisocial behavior problem subtype.48 It is likely that, along with important environmental influences, aggression and delinquent behavior share some common genetic basis. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that delinquent behavior and EFD are even more closely co-morbid – representing different phenotypic manifestations of the same predisposition that appear over the life span in an age-graded pattern (i.e., with delinquency before early alcohol use, and with a distinct link between preschool and adolescent rule-breaking).

There are several limitations to our study. Our sample was racially and geographically homogeneous (mostly Caucasian and from the Midwest) and biased toward paternal psychopathology. Only male children were included because MLS data collection on daughters started in later years so only a small number (approximately n=20) had data spanning preschool through early adolescence at the time of this study. Finally, missing data resulted in dropped cases and a sample with less psychopathology than the full MLS sample. In some ways this becomes a conservative test of our hypotheses. On the other hand, it becomes less difficult to compare this more normative group to other lower-risk, general population samples.

In conclusion, findings from the current study are robust in their consistency. Onset of drinking was more strongly tied to the developmental course of delinquent behavior than aggression, with predispositions having an especially important influence on adolescent outcomes for early drinkers only. One practical implication of this common diathesis is that a high level of delinquent behavior in the preschool years should serve as a warning sign to parents and physicians. Children with such symptomatology are prime candidates for early intervention programs which may possibly also prevent early onset of alcohol use and related sequelae.49 Programs that focus only on trying to delay first alcohol use will probably fail to prevent later alcohol problems because it is likely that both are part of a larger, self-perpetuating developmental trajectory.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant R37 AA07065 to Robert A. Zucker and Hiram E. Fitzgerald, and by a Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation grant to Roni Mayzer.

We thank Leon I. Puttler and Susan K. Refior, whose long term and dedicated work with MLS families has been essential to the study’s viability. We also are grateful to the MLS families who have continued for so long to share their life stories with us.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gruber E, DiClemente RJ, Anderson MM, Lodico M. Early onset drinking and its association with alcohol use and problem behavior in adolescence. Prev Med. 1996;25(3):293–300. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGue M, Iacono WG, Legrand LN, Malone S, Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink, I. Associations with substance-use disorders, disinhibitory behavior, and psychopathology, and P3 amplitude. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(8):1156–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Age at first drink and risk for alcoholism: A noncausal association. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23(1):101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuckit MA, Russell JW. Clinical importance of age at first drink in a group of young men. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(9):1221–1223. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.9.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeWit DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, Ogborne AC. Age at first alcohol use: A risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):745–750. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: Age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(7):739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babor TF. The classification of alcoholics: Typology theories from the 19th century to the present. Alcohol Health Res World. 1996;20(1):6–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cloninger CR, Sigvardsson S, Bohman M. Type I and type II alcoholism: An update. Alcohol Health Res World. 1996;20(1):18–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zucker RA. The four alcoholisms: A developmental account of the etiologic process. In: Rivers PC, editor. Alcohol and Addictive Behavior. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1987. pp. 27–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zucker RA. Alcohol use and the alcohol use disorders: A developmental-biopsychosocial formulation covering the life course. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental Psychopathology: Volume 3: Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation. 2. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 620–656. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Growing up in an alcoholic family: Pathways of risk aggregation for alcohol use disorders. In: Freeark K, Davidson W III, editors. The Crisis in Youth Mental Health, Volume 3: Families, Schools, and Communities. Westport, CT: Praeger Press; 2005. pp. 249–271. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzgerald HE, Puttler LI, Mun EY, Zucker RA. Prenatal and postnatal exposure to parental alcohol use and abuse. In: Osofsky JD, Fitzgerald HE, editors. WAIMH Handbook of Infant Mental Health: Volume 4. Infant Mental Health in Groups at High Risk. New York: Wiley; 2000. pp. 123–159. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moffitt TE. Life-course-persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev. 1993;100(4):674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2006. Volume I: Secondary School Students. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2007. NIH Publication No. 07–6205. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. Vol. 55. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance — United States, 2005; pp. 1–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuperman S, Chan G, Kramer JR, et al. Relationship of age of first drink to child behavioral problems and family psychopathology. Alcohol Clinical Exp Res. 2005;29(10):1869–1876. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000183190.32692.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sartor CE, Lynskey MT, Heath AC, Jacob T, True W. The role of childhood risk factors in initiation of alcohol use and progression to alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2007;102(2):216–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem Behavior and Psychosocial Development: A Longitudinal Study of Youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Perez CM. The interrelationship between substance use and precocious transitions to adult statuses. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38(1):87–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. Factors associated with continuity and changes in disruptive behavior patterns between childhood and adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1996;24(5):533–553. doi: 10.1007/BF01670099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: Developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(7):709–717. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simonoff E, Elander J, Holmshaw J, Pickles A, Murray R, Rutter M. Predictors of antisocial personality: Continuities from childhood to adult life. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184(2):118–127. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cernkovich SA, Giordano PC. Stability and change in antisocial behavior: The transition from adolescence to early adulthood. Criminology. 2001;39(2):371–410. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrington DP. The development of offending and antisocial behaviour from childhood: Key findings from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1995;36(6):929–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagin DS, Farrington DP. The stability of criminal potential from childhood to adulthood. Criminology. 1992;30(2):235–260. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sampson RJ, Laub JH. Crime in the making: Pathways and Turning Points Through Life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Broidy LM, Nagin DS, Tremblay RE, et al. Developmental trajectories of childhood disruptive behaviors and adolescent delinquency: A six-site, cross-national study. Dev Psychol. 2003;39(2):222–245. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cairns RB, Cairns BD, Neckerman HJ, Ferguson LL, Gariépy J-L. Growth and aggression: I. Childhood to early adolescence. Dev Psychol. 1989;25(2):320–330. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eron LD, Huesmann LR, Dubow E, Romanoff R, Yarmel PW. Aggression and its correlates over 22 years. In: Crowell DH, Evans IM, O’Donnell CR, editors. Childhood Aggression and Violence: Sources of Influence, Prevention, and Control. New York: Plenum Press; 1987. pp. 249–262. [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Beijsterveldt CEM, Bartels M, Hudziak JJ, Boomsma DI. Causes of aggression from early childhood to adolescence: A longitudinal genetic analysis in Dutch twins. Behav Genet. 2003;33(5):591–605. doi: 10.1023/a:1025735002864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haberstick BC, Schmitz S, Young SE, Hewitt JK. Genes and developmental stability of aggressive behavior problems at home and school in a community sample of twins aged 7–12. Behav Genet. 2006;36(6):809–819. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loeber R. The stability of antisocial and delinquent behavior: A review. Child Dev. 1982;53(6):1431–1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olweus D. Stability of aggressive reaction patterns in males: A review. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(4):852–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartels M, Hudziak JJ, van den Oord EJCG, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Rietveld MJH, Boomsma DI. Co-occurence of aggressive behavior and rule-breaking behavior at age 12: Multi-rater analyses. Behav Genet. 2003;33(5):607–621. doi: 10.1023/a:1025787019702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Achenbach TM, Edelbrock C. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University Associates in Psychiatry; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barnow S, Lucht M, Freyberger HJ. Correlates of aggressive and delinquent conduct problems in adolescence. Aggress Behav. 2005;31(1):24–39. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tuvblad C, Eley TC, Lichtenstein P. The development of antisocial behaviour from childhood to adolescence: A longitudinal twin study. Eur Child Adoles Psychiatry. 2005;14(4):216–225. doi: 10.1007/s00787-005-0458-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edelbrock C, Rende R, Plomin R, Thompson LA. A twin study of competence and problem behavior in childhood and early adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1995;36(5):775–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bongers IJ, Koot HM, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. The normative development of child and adolescent problem behavior. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(2):179–192. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanger C, Achenbach TM, Verhulst FC. Accelerated longitudinal comparisons of aggressive versus delinquent syndromes. Dev Psychopathol. 1997;9(1):43–58. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Achenbach TM. Assessment and Taxonomy of Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE, Refior SK, Puttler LI, Pallas DM, Ellis DA. The clinical and social ecology of childhood for children of alcoholics: Description of a study and implications for a differentiated social policy. In: Fitzgerald HE, Lester BM, Zuckerman BS, editors. Children of Addiction: Research, Health, and Public Policy Issues. New York: Routledge Publishers; 2000. pp. 109–141. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Little RJA. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83(404):1198–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 46.von Eye A. Configural Frequency Analysis: Methods, Models, and Applications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lehmacher W. A more powerful simultaneous test procedure in configural frequency analysis. Biom J. 1981;23(5):429–436. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zucker RA. The developmental behavior genetics of drug involvement: Overview and comments. Behav Genet. 2006;36(4):616–625. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9070-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Biglan A, Brennan PA, Foster SL, et al. Helping Adolescents at Risk: Prevention of Multiple Problem Behaviors. New York: Guilford; 2004. [Google Scholar]