Abstract

The spliceosome, a dynamic assembly of proteins and RNAs, catalyzes the excision of intron sequences from nascent mRNAs. Recent work has suggested that the activity and composition of the spliceosome are regulated by ubiquitination, but the underlying mechanisms have not been elucidated. Here, we report that the spliceosomal Prp19 complex modifies Prp3, a component of the U4 snRNP, with nonproteolytic K63-linked ubiquitin chains. The K63-linked chains increase the affinity of Prp3 for the U5 snRNP component Prp8, thereby allowing for the stabilization of the U4/U6.U5 snRNP. Prp3 is deubiquitinated by Usp4 and its substrate targeting factor, the U4/U6 recycling protein Sart3, which likely facilitates ejection of U4 proteins from the spliceosome during maturation of its active site. Loss of Usp4 in cells interferes with the accumulation of correctly spliced mRNAs, including those for α-tubulin and Bub1, and impairs cell cycle progression. We propose that the reversible ubiquitination of spliceosomal proteins, such as Prp3, guides rearrangements in the composition of the spliceosome at distinct steps of the splicing reaction.

Keywords: Ubiquitin, K63-linked ubiquitin chains, splicing, Prp19 complex, Usp4

Reversible post-translational modifications are known to regulate protein interactions (Seet et al. 2006). These modifications can be brought about by tightly regulated enzymes, interpreted by modular proteins with specialized modification-binding domains, and removed by an opposing class of enzymes. Phosphorylation has been the paradigm for this type of signaling, and many kinases, phosphate-binding domains, and phosphatases have been isolated.

Research in the past two decades has shown that reversible ubiquitination is used widely in signaling (Kerscher et al. 2006; Chen and Sun 2009). The modification of proteins with ubiquitin requires a cascade of at least three enzymes, referred to as E1, E2, and E3 (Deshaies and Joazeiro 2009; Ye and Rape 2009). E1 activates ubiquitin and transfers it as a thioester to the active site Cys of an E2. The ubiquitin-charged E2 and substrates are then recruited by an E3, which results in the formation of an isopeptide bond between the C terminus of ubiquitin and an amino group of a substrate lysine. Approximately 600 human E3s have a RING domain to bind and activate E2s (Deshaies and Joazeiro 2009), but domains with structural and functional homology with the RING domain, such as the U-box, have also been described (Koegl et al. 1999; Patterson 2002).

The transfer of ubiquitin to a lysine of a substrate-attached ubiquitin molecule leads to the formation of ubiquitin chains. Depending on which lysine of ubiquitin is used, these chains differ in structure and function. For example, K11- or K48-linked chains trigger the degradation of modified proteins by the 26S proteasome (Kerscher et al. 2006; Jin et al. 2008; Williamson et al. 2009). In contrast, K63-linked chains usually do not result in proteolysis, but attract binding partners with specialized ubiquitin recognition domains (Grabbe and Dikic 2009). In this manner, K63-linked chains regulate protein localization, assembly of DNA repair complexes, or activation of the NF-κB transcription factor (Chen and Sun 2009).

The activity of E3s in assembling ubiquitin chains is opposed by deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), which contain catalytic USP, UCH, OTU, MJD, or JAMM domains (Nijman et al. 2005; Song and Rape 2007; Reyes-Turcu et al. 2009). E3s and their counteracting DUBs often bind each other, which allows for dynamic ubiquitination of a common substrate (Sowa et al. 2009). Some DUBs—such as the K63-specific Cyld, AMSH, or Brcc36—cleave ubiquitin chains of a specific topology (Komander et al. 2008; Sato et al. 2008; EM Cooper et al. 2009). Most DUBs containing a USP domain, however, are able to disassemble multiple chain types, and their specificity in cells is determined by dedicated substrate targeting factors (Reyes-Turcu et al. 2009). The loss of K63-specific DUBs can prolong ubiquitin-dependent signaling and lead to diseases (Courtois and Gilmore 2006). Although it is evident that reversible ubiquitination is pivotal for signaling, in only a few cases are the E3s, DUBs, and substrates all known.

As one of the most dynamic complexes in human cells, the spliceosome is an attractive candidate for ubiquitin-dependent regulation. The spliceosome is assembled on intron-containing mRNAs by recognition of the 5′-splice site by the U1 snRNP, and the branch point and 3′-splicing site by U2AF and SF1/BBP (Wahl et al. 2009). Following the binding of the U2 snRNP, the U4/U6.U5 snRNP is recruited. Upon formation of the spliceosomal active site, the U1 and U4 snRNAs and their associated proteins are released. After intron excision has been completed, the spliceosome is disassembled, and its components are recycled for subsequent rounds of splicing. Thus, the spliceosome undergoes rapid and tightly regulated changes in its composition during its catalytic cycle, with distinct proteins and RNAs associating and dissociating at defined stages of the splicing reaction (Jurica and Moore 2003; Maeder and Guthrie 2008). The reversible attachment of ubiquitin chains could help orchestrate the structural rearrangements during the splicing reaction.

Indeed, ubiquitin has been suspected to regulate the spliceosome, since the spliceosomal protein Prp19 was found to contain a U-box, allowing it to ubiquitinate itself in vitro (Aravind and Koonin 2000; Ohi et al. 2003). Prp19 is a component of the essential Prp19 complex (Nineteen Complex [NTC]), which contains >30 proteins (Wahl et al. 2009). Mutations in Prp19 destabilize the spliceosomal U4/U6 snRNP and affect anchoring of the U6 snRNA to the spliceosome in yeast (Chan et al. 2003; Chen et al. 2006; Wahl et al. 2009). Recently, ubiquitination has been shown to be required both for splicing and the integrity of the U4/U6.U5 snRNP in yeast extracts, and Prp8, a component of the U5 snRNP, was found to be ubiquitinated in this organism (Bellare et al. 2008). However, substrates of Prp19/NTC or DUBs counteracting this E3 have not been identified. It is not known whether ubiquitination regulates interactions or degradation of spliceosomal proteins, and thus mechanisms underlying the ubiquitin-dependent regulation of splicing have not been established.

Here, we report that Prp19/NTC modifies Prp3, a component of the U4 snRNP (Nottrott et al. 2002), with K63-linked ubiquitin chains. The K63-linked chains increase the affinity of Prp3 for the U5 component Prp8 to stabilize the U4/U6.U5 snRNP. As U4 proteins need to be ejected from the spliceosome during maturation of its active site, Prp3 is deubiquitinated by Usp4 and its substrate targeting subunit, the U4/U6 recycling factor Sart3. The loss of Usp4 activity in cells interferes with splicing, cell division, and a proper response to the chemotherapeutic taxol. We propose that the reversible ubiquitination of spliceosomal proteins such as Prp3 guides rearrangements in the composition of the spliceosome at distinct steps of the splicing reaction.

Results

Usp4 is required for cell cycle control

We recently developed a strategy to identify proteins required for cell cycle control that allowed us to isolate the DUB Usp44 as a mitotic regulator (Stegmeier et al. 2007). In our original screen, we transfected HeLa cells with shRNAs to deplete candidate ubiquitin-related proteins, and interrupted cell cycle progression by addition of taxol. Drug-treated cells were screened for a reduced number of mitotic cells in the presence of the shRNA, which can result from cell cycle delay and premitotic arrest (cells have a single nucleus) (see Stegmeier et al. 2007), or from failure to mount or maintain a spindle checkpoint arrest (multinucleated cells; multilobed nuclei).

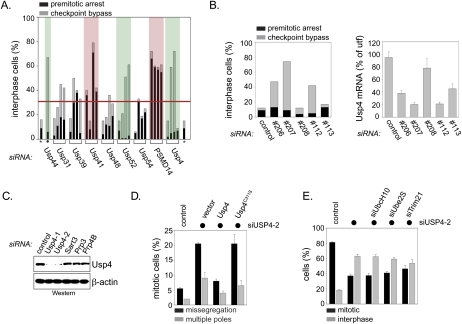

Here, we analyzed the role of DUBs in cell cycle control in more detail by using a siRNA library targeting ∼70 human DUBs. We transfected HeLa cells with pooled siRNA against the DUBs before adding taxol, nocodazole, or monastrol to inhibit progression of cells through mitosis. Twenty-four hours after the drug treatment, we calculated the mitotic index and scored for premitotic arrest or multinucleation (Supplemental Fig. 1). Subsequently, screen hits were validated using four individual siRNAs. Depletion of Usp41 or the proteasomal DUB PSMD14 resulted in premitotic arrest (Fig. 1A). In addition to Usp44, which was also identified in this screen (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Fig. 1), the depletion of Usp4 and Usp52 led to significant spindle checkpoint bypass (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Usp4 is required for faithful cell cycle progression. (A) Identification of human DUBs that regulate the cell cycle. Candidate DUBs identified in three parallel siRNA screens were depleted in HeLa cells by four independent siRNAs. HeLa cells were treated with taxol, and, 24 h later, the percentage of cells arrested prior to mitosis (black bar) and the number of cells unable to maintain a spindle checkpoint arrest (gray bar) were determined. siRNA against luciferase (*) and against Usp44 (•) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. A percentage of >30% nonmitotic cells was set as an arbitrary threshold for specificity (red line). DUBs whose depletion by at least two siRNAs predominantly results in premitotic arrest are labeled in red, whereas DUBs required for a stable checkpoint response are labeled in green. (B) The efficiency of Usp4 depletion matches the strength of its cell cycle phenotypes. Five different siRNAs against Usp4 were tested for effects on cell cycle progression (left panel) and efficiency of mRNA depletion (right panel), as determined by RT–PCR. The abundance of mRNAs is shown in comparison with untransfected (utf) control cells. (C) siRNAs against the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of Usp4 deplete the Usp4 protein from cells. Two independent siRNAs against the 3′-UTR of Usp4 were tested for their effect on depletion of Usp4, compared with the loading control β-actin, as determined by Western blot. (D) The activity of Usp4 as a DUB is required for its role in cell cycle control. HeLa cells were treated against siRNA against the 3′-UTR of Usp4, and the number of mitotic cells with errors in chromosome segregation (black bars) or spindle formation (gray bars) was determined. When indicated, cells were also transfected with vectors encoding siRNA-resistant Usp4 or the catalytically inactive Usp4C311A. (E) Usp4 does not directly counteract the E3s APC/C or Trim21. HeLa treated with siRNA against Usp4 and taxol were scored for the percentage of interphase cells. When indicated, siRNAs against UbcH10, Ube2S, or Trim21 were cotransfected.

The chromosomal location of the USP4 gene 3p21.31 is frequently deleted in small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), and reduced expression of Usp4 had been described in SCLC cell lines (Frederick et al. 1998). Moreover, SCLC is refractory to most regimes of chemotherapy, including treatment with taxol (Hann and Rudin 2007). Because SCLCs are also often aneuploid (Hann and Rudin 2007), a phenotype expected from loss of spindle checkpoint control, we initially analyzed the role of Usp4 in cell cycle control. By testing multiple siRNAs targeting USP4, we observed a quantitative correlation between knockdown efficiency and spindle checkpoint bypass (Fig. 1B). Moreover, as seen with other mitotic regulators (Wong and Fang 2006), depletion of Usp4 led to chromosome missegregation and defects in spindle structure in the absence of spindle toxins (Fig. 1C,D). These phenotypes were rescued by expression of a siRNA-resistant Usp4, but not inactive Usp4C311A, demonstrating that its DUB activity is required for the role of Usp4 in cell cycle control (Fig. 1D).

The depletion of Usp44 leads to premature activation of the mitotic E3 APC/C, which could be rescued by codepletion of the APC/C-specific E2s UbcH10 or Ube2S (Stegmeier et al. 2007; Williamson et al. 2009). In contrast, Usp4 depletion was not rescued by parallel depletion of UbcH10 or Ube2S (Fig. 1E), indicating that Usp4 does not counteract the APC/C. Usp4 has also been described to bind the E3 Trim21 (Wada et al. 2006), but codepletion of Trim21 had no effects on the cell cycle defects caused by loss of Usp4 (Fig. 1E). Thus, Usp4 likely acts independently of the APC/C or Trim21.

Identification of the Usp4Sart3 DUB complex

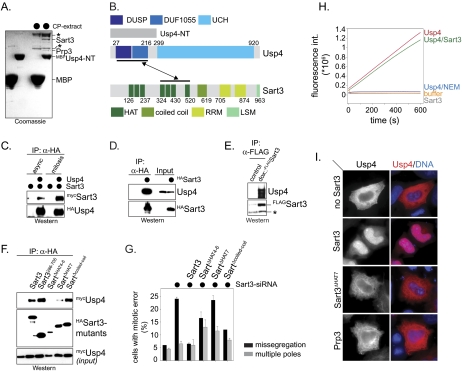

As many DUBs require accessory proteins as catalytic activators or substrate targeting factors (Cohn et al. 2007; Reyes-Turcu et al. 2009), we isolated interaction partners of Usp4 by incubating its regulatory domain (MBPUsp4-NT) with extracts of mitotic HeLa S3 cells. Proteins specifically retained by MBPUsp4-NT were identified by mass spectrometry. This strategy led to the isolation of Sart3, which efficiently associated with MBPUsp4-NT, but not with MBP (Fig. 2A). Sart3 is a recycling factor of the U4/U6 spliceosomal snRNP, which promotes the reannealing of U4 and U6 snRNPs following the ejection of the U4 snRNP from the spliceosome during the maturation of the spliceosomal active site (Fig. 2B; Bell et al. 2002; Trede et al. 2007). This suggests that Usp4 might play a role in regulating the function or composition of the spliceosome.

Figure 2.

Sart3 is a targeting factor of Usp4. (A) Identification of Sart3 as a binding partner of Usp4. The regulatory domain of Usp4 was fused to MBP (MBPUsp4-NT; amino acids 1–296). Immobilized MBP and MBPUsp4-NT were incubated with extracts of mitotic HeLa S3 cells (CP extracts). Proteins retained by MBPUsp4-NT, but not MBP, were detected by Coomassie staining and identified by mass spectrometry. The asterisks mark proteins that were retained by both MBP and MBPUsp4-NT; we did not identify these unspecific binding partners. (B) Schematic overview of Sart3 and its interaction with Usp4. Sart3 consists of seven HAT repeats, one coiled-coil, two RNA recognition motifs, and one LSM domain. The HAT repeat 7 of Sart3 is required for the interaction with the partially overlapping DUSP and DUF1055 domains of Usp4. (C) Sart3 binds Usp4 in vivo. HeLa cells were transfected with mycSart3 and HAUsp4, and were grown asynchronously or arrested in mitosis by nocodazole. HAUsp4 was purified on αHA-agarose, and coprecipitating mycSart3 was detected by αmyc-Western blot. (D) Sart3 binds endogenous Usp4. HASart3 was expressed in HeLa cells and purified on αHA-agarose. Coprecipitating endogenous Usp4 was detected by Western blot using αUsp4 antibodies. (E) Usp4 and Sart3 interact under physiological conditions. We generated a stable U2OS cell line that inducibly expresses FlagSart3 at low concentrations upon addition of doxycycline to the medium. FlagSart3 was purified by αFlag immunoprecipitation, and coprecipitating endogenous Usp4 was detected by Western blotting using αUsp4 antibodies. The asterisk denotes a nonspecific band. (F) The HAT7 domain of Sart3 is required for the interaction with Usp4. HeLa cells were cotransfected with HA-tagged deletion mutants of Sart3 and mycUsp4, and the interaction of the Sart3 mutants with Usp4 was analyzed by αHA-affinity purification. Coprecipitating mycUsp4 was detected by αmyc-Western blotting. Expression of Sart3ΔHAT4–6 appeared to be toxic in HeLa cells, complicating the interpretation of results with this mutant. (G) The interaction with Usp4 is required for the role of Sart3 as a cell cycle regulator. Sart3 was depleted from HeLa cells using siRNA against the 3′-UTR of Sart3, and the percentage of mitotic cells with obvious chromosome missegregation or spindle defects was determined. As indicated, cells were cotransfected with siRNA-resistant Sart3 or deletion mutants. Similar to Usp4, depletion of Sart3 results in chromosome missegregation (black bars). The Usp4-binding-deficient Sart3ΔHAT7 is unable to rescue these phenotypes. (H) Sart3 does not activate Usp4. The DUB activity of Usp4 was measured by monitoring the release of the fluorophore AMC from the C terminus of ubiquitin, which results in an increase of the fluorescence signal at 469 nm. The activities of Usp4, Usp4 inactivated with NEM, and the Usp4Sart3 complex were compared. (I) Sart3 functions as a targeting factor of Usp4. The intracellular localization of mycUsp4 was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Expression of Sart3 (as indicated on the left) results in nuclear translocation of Usp4. Coexpression of the Usp4-binding-deficient Sart3ΔHAT7 or the nuclear protein Prp3 had no effect on the localization of Usp4.

To confirm the interaction between Usp4 and Sart3, we expressed HAUsp4 and mycSart3 in HeLa cells and purified Usp4 complexes by affinity chromatography against the HA epitope. These experiments revealed a strong interaction between Usp4 and Sart3 (Fig. 2C). Conversely, endogenous Usp4 was precipitated efficiently by HASart3 affinity purification (Fig. 2D). To determine whether Usp4 and Sart3 interact under more physiological settings, we generated a U2OS cell line that inducibly expresses FlagSart3 at low concentrations. As detected by immunoprecipitation, we found that endogenous Usp4 also interacted with Sart3 under these conditions (Fig. 2E).

The interaction between Usp4 and Sart3 was found to be direct, as MBPSart3 associated with Usp4 synthesized by in vitro transcription/translation (IVT/T) (Supplemental Fig. 2A), and purified HISSart3 strongly bound MBPUsp4 (see Fig. 3C). The interaction between Usp4 and Sart3 required the DUSP and DUF1055 domains in Usp4 and the HAT7 domain in Sart3 (Fig. 2F; Supplemental Fig. 2B). Similar to Usp4, siRNA depletion of Sart3 resulted in chromosome missegregation during mitosis, which could be rescued by expression of siRNA-resistant Sart3, but not Usp4-binding-deficient Sart3ΔHAT7 (Fig. 2G). Thus, the interaction with Usp4 is important for the role of Sart3 in cell cycle control.

Figure 3.

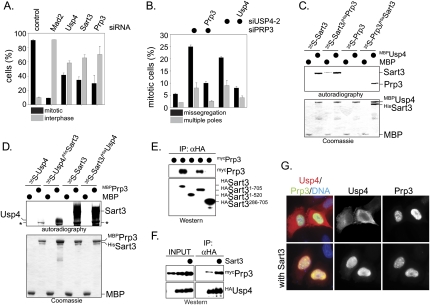

Sart3 recruits Prp3 to Usp4. (A) Depletion of Prp3 causes a cell cycle defect. HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA against Mad2, Usp4, Sart3, and Prp3 and treated with taxol. After 24 h, the percentage of cells in mitosis (black bars) and interphase (gray bars) was determined by microscopy. (B) Depletion of Prp3 results in chromosome missegregation. HeLa cells were transfected with siRNA against Prp3 or Usp4. As indicated, siRNA-resistant cDNA encoding Prp3 or Usp4 was cotransfected. Mitotic cells were analyzed for chromosome missegregation and spindle defects after immunofluorescence against α-tubulin and DNA. (C) Sart3 recruits Prp3 to Usp4. MBP or MBPUsp4 was immobilized on amylose resin and incubated with 35S-Sart3 or 35S-Prp3. As indicated, recombinant HisPrp3 or HisSart3 was added. Bound proteins were detected by autoradiography. Radiolabeled Prp3 interacts with MBPUsp4 only in the presence of HisSart3. (D) Sart3 recruits Usp4 to Prp3. MBP or MBPPrp3 was immobilized on amylose resin and incubated with 35S-Usp4 or 35S-Sart3. When indicated, recombinant HisSart3 or HisUsp4 was added, and bound proteins were detected by autoradiography. HisSart3 comigrates with MBPPrp3. The asterisk denotes an unknown protein in reticulocyte lysate that interacts with MBPPrp3. (E) The N terminus of Sart3 binds Prp3. HASart3 or the indicated deletion mutants were coexpressed with mycPrp3, and were affinity-purified on αHA-agarose. Bound mycPrp3 was detected by αmyc-Western blotting. Note that Sart3286-705, which efficiently interacts with Usp4, fails to bind Prp3. (F) Coexpression of Sart3 increases the efficiency of the Usp4–Prp3 interaction. HeLa cells were cotransfected with HAUsp4, mycPrp3, and, as indicated, Sart3. Usp4 complexes were affinity-purified on αHA-agarose, and bound mycPrp3 was detected by αmyc-Western blot. (G) Sart3 triggers the colocalization of Prp3 and Usp4. The localization of HAUsp4 (red) and mycPrp3 (green) in HeLa cells was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy in the absence (top panels) or presence (bottom panels) of coexpressed Sart3.

Sart3 may increase the catalytic activity of Usp4, as observed for cofactors of several DUBs (Cohn et al. 2007). To test this hypothesis, we measured the DUB activity of recombinant Usp4 in the presence or absence of Sart3. As determined by Western blotting, Usp4 alone was able to disassemble both K48- and K63-linked ubiquitin chains (Supplemental Fig. 2C). We observed a slight but reproducible preference of Usp4 for K63-linked chains, which were completely disassembled, while K48-linked chains with four or five ubiquitin molecules appeared to be less optimal substrates. In a complementary assay, Usp4 also cleaved a fluorescent reporter off the C terminus of ubiquitin (Fig. 2H). Sart3 did not promote deubiquitination on its own (Supplemental Fig. 2D), and addition of Sart3 did not increase the activity of Usp4 in any of our assays (Fig. 2H; Supplemental Fig. 2E), suggesting that Sart3 does not function as a catalytic activator of Usp4.

Alternatively, Sart3 might recruit Usp4 to ubiquitinated substrates. Sart3 localizes to the nucleus (Staněk et al. 2003), whereas exogenously expressed Usp4 accumulated in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2I; Frederick et al. 1998; Wada et al. 2006). When the expression levels of Sart3 were increased, Usp4 was recruited efficiently to the nucleus, which depended on an intact Usp4-binding domain in Sart3 (Fig. 2I). Fusion of a nuclear localization sequence (NLS) to Usp4 was sufficient to trigger its import into the nucleus, suggesting that Usp4 lacks a strong NLS of its own (Supplemental Fig. 2F). Accordingly, we found that Sart3 recruited Usp4 to the transport receptor importin-α in vitro (Supplemental Fig. 2G). Overall, our results suggest that Sart3 is a targeting factor, rather than a catalytic activator, of Usp4. Thus, we hereafter refer to the DUB complex consisting of Usp4 and Sart3 as Usp4Sart3.

Prp3 is a substrate of Usp4Sart3

We observed a second protein that was retained by MBPUsp-NT, but not MBP, albeit less abundantly (Fig. 2A). This protein was identified by mass spectrometry as Prp3, a key component of the spliceosomal U4 snRNP and known interactor of Sart3 (Nottrott et al. 2002; Medenbach et al. 2004). Depletion of Prp3 from HeLa cells resulted in similar spindle checkpoint bypass and chromosome missegregation as loss of Usp4 or Sart3, and these phenotypes could be rescued by expression of siRNA-resistant Prp3 (Fig. 3A,B). We therefore considered the possibility that Prp3 is a substrate of Usp4Sart3.

Prp3 directly associated with MBPSart3, but not with MBPUsp4 (Fig. 3C; Supplemental Fig. 2A). In addition, MBPPrp3 precipitated radiolabeled Sart3, but not Usp4 (Fig. 3D). As reported previously, Sart3 required its N terminus to interact with Prp3, which is distinct from its Usp4-binding site (Fig. 3E; Supplemental Fig. 3A; Medenbach et al. 2004). This should allow Sart3 to bridge the interaction between Prp3 and Usp4, and, indeed, addition of HisSart3 strongly increased the binding of Prp3 to MBPUsp4 and of Usp4 to MBPPrp3 in vitro (Fig. 3C,D). The expression of Sart3 in vivo induced the nuclear colocalization of Prp3 and Usp4 and enhanced the interaction between Prp3 and Usp4 in cells (Fig. 3F,G). Thus, as expected for a substrate targeting factor, Sart3 recruits Usp4 to Prp3.

To be a substrate of Usp4Sart3, Prp3 would have to be ubiquitinated in cells. We observed modified forms of Prp3 upon increasing the concentration of ubiquitin in HeLa cells (Supplemental Fig. 3B). As shown by denaturing NiNTA pull-down, the modified forms represent Prp3 covalently modified with ubiquitin (see Fig. 5B,C, below). Using mass spectrometry, we found endogenous Prp3 to be ubiquitinated on at least two Lys residues in cells (M Sowa, E Bennett, and W Harper, pers. comm.). As an initial test of whether the ubiquitinated Prp3 is a substrate for Usp4, we coexpressed Prp3 together with Usp4 or inactive Usp4C311A and measured the abundance of the ubiquitinated species by Western blot. Usp4, but not inactive Usp4C311A or the unrelated Usp44, led to deubiquitination of Prp3 in cells (Supplemental Fig. 3B,C). In contrast, Usp4 did not strongly affect the ubiquitination status of other snRNP components, such as U4-Prp4 or U6-Lsm2, which were also ubiquitinated under these conditions (Supplemental Fig. 3D,E). In addition, Prp3 complexes purified from HeLa cells contained ubiquitin conjugates, which were disassembled efficiently by recombinant Usp4Sart3 (Supplemental Fig. 3F). Together, these data suggest that Prp3 is a substrate of Usp4Sart3.

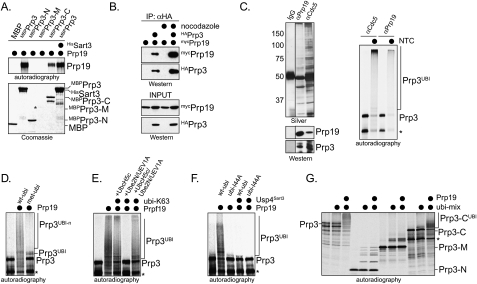

Figure 5.

The Prp19 complex (NTC) promotes the ubiquitination of Prp3 in vivo. (A) Expression of Prp19 triggers the modification on Prp3 in cells. mycPrp3 was coexpressed with Prp19 or the E3 Trim21 in HeLa cells, and was analyzed for modifications by αmyc-Western blot. (B) Prp19 promotes the ubiquitination of Prp3 in HeLa cells. mycPrp3, Prp19, and Hisubiquitin were expressed in HeLa cells as indicated. HisUbiquitin and covalently modified proteins were purified from cells under denaturing conditions on NiNTA-agarose. Copurifying ubiquitinated mycPrp3 was detected by αmyc-Western blot. (C) The NTC promotes the ubiquitination of endogenous Prp3 in cells. Prp19 and Hisubiquitin were expressed in HeLa cells as indicated, and ubiquitinated proteins were purified on NiNTA-agarose under denaturing conditions. Ubiquitinated endogenous Prp3 was detected by Western blotting using specific αPrp3 antibodies. (D) The NTC ubiquitinates the C-terminal domain of Prp3 in cells. The myc-tagged truncation mutants Prp3-N, Prp3-M, and Prp3-C were expressed in HeLa cells. Where indicated, Prp19 was coexpressed, and the modification of the Prp3 proteins was analyzed by αmyc-Western blot. (E) Depletion of Prp19 by siRNA reduces the ubiquitination of Prp3 in HeLa cells. The ubiquitination of mycPrp3 was analyzed in HeLa cells by αmyc-Western blot, after Prp19 was depleted by a specific siRNA targeting its 3′-UTR. (F) The NTC promotes the modification of Prp3 with K63-linked chains in cells. mycPrp3 and Prp19 were expressed in HeLa cells, as indicated. The coexpression was performed in the presence of wt-ubi, ubi-R48 (which has Lys48 mutated to Arg), or ubi-R63. (G) The NTC promotes the modification of Prp3 with K63-linked chains, as detected by denaturing purification of ubiquitin conjugates. mycPrp3 and Prp19 were expressed in HeLa cells with the indicated Hisubiquitin mutants. Ubiquitin conjugates were purified by denaturing NiNTA pull-down, and mycPrp3 was detected by αmyc-Western blotting.

The Prp19 complex is a ubiquitin ligase for Prp3

To dissect the role of Prp3 deubiquitination by Usp4Sart3, we needed to identify the E3 catalyzing Prp3 ubiquitination. A candidate Prp3-E3 is the Prp19 complex (NTC), which, among ∼30 proteins, contains the cell division cycle protein Cdc5 and the U-box protein Prp19 (Wahl et al. 2009). Mutations within the U-box of Prp19 destabilize the U4/U6 snRNP, which includes Prp3 (Lygerou et al. 1999; Ohi et al. 2003; Chen et al. 2006). We first tested whether Prp19 interacts with Prp3, and found Prp19 to be specifically retained by MBPPrp3 in pull-down assays (Fig. 4A). Deletion analysis showed that the C-terminal domain of Prp3 and the WD40 repeats of Prp19 were sufficient to support this interaction (Fig. 4A; Supplemental Fig. 4A). As shown by immunoprecipitation, Prp3 associated with Prp19 in HeLa cells when coexpressed (Fig. 4B), and endogenous Prp3 was found to bind the endogenous NTC purified by antibodies against Prp19 or Cdc5 (Fig. 4C). Although Sart3 also binds the C terminus of Prp3 (Supplemental Fig. 3A), an excess of Sart3 did not block the interaction between Prp3 and Prp19 (Fig. 4A). In fact, we found that Usp4 and Prp19 could be detected in the same complexes in reticulocyte lysates and in vivo (Supplemental Fig. 4B–D), consistent with the observation that E3s and DUBs share binding partners to allow the dynamic ubiquitination of common substrates (Sowa et al. 2009).

Figure 4.

Prp3 is ubiquitinated by the Prp19 complex in vitro. (A) Prp19 associates with Prp3 in vitro. MBP, MBPPrp3, and MBP-tagged truncation mutants of Prp3 were immobilized on amylose resin, and were incubated with 35S-Prp19. Bound Prp19 was detected by autoradiography. Purified MBPPrp3-M does not bind efficiently to beads, and thus cannot be analyzed (its position is marked by an asterisk). (B) Prp19 associates with Prp3 in vivo. HeLa cells were cotransfected with HAPrp3 and mycPrp19. HAPrp3 was affinity-purified on αHA-agarose, and copurifying Prp19 was detected by αmyc-Western blot. When indicated, cells were synchronized in mitosis with nocodazole prior to the immunoprecipitation. (C) The Prp19 complex ubiquitinates Prp3 in vitro. The Prp19 complex was affinity-purified from HeLa S3 cells by using αPrp19-agarose or αCdc5-agarose. Complexes were analyzed by silver staining (left panel) or Western blotting (bottom left panel) using specific antibodies against Prp19 and Prp3. Beads were incubated with 35S-Prp3 for 2 h. Unbound proteins were washed away, before the NTC/Prp3 complexes were incubated with purified E1, UbcH5c, ubiquitin, and energy mix. Ubiquitinated Prp3 was detected by autoradiography. The asterisk marks an N-terminally truncated Prp3 resulting from alternative start codon usage in the IVT/T. (D) The Prp19 complex forms ubiquitin chains on Prp3. 35S-Prp3 was ubiquitinated by the Prp19 complex and UbcH5c in the presence of ubiquitin or methylubiquitin, which is unable to support ubiquitin chain formation. Ubiquitinated Prp3 was detected by autoradiography. The asterisk marks an N-terminally truncated Prp3 resulting from alternative start codon usage in the IVT/T reaction. (E) The Prp19 complex can assemble K63-linked ubiquitin chains in vitro. The Prp19 complex was used to catalyze the ubiquitination of 35S-Prp3 in the presence of ubiquitin or ubiquitin with Lys63 as its only lysine residue (ubi-K63). As E2s, UbcH5c, Ube2N/UEV1A, or UbcH5c and Ube2N/UEV1A were used. Ubiquitinated Prp3 was detected by autoradiography. The asterisk marks an N-terminally truncated Prp3 resulting from alternative start codon usage in the IVT/T reaction. (F) The Prp19 complex requires the hydrophobic patch on ubiquitin to support chain formation on Prp3. Ubiquitination of 35S-Prp3 was catalyzed by the Prp19 complex in the presence of ubiquitin or the mutant ubi-I44A. As a comparison, the ubiquitination of Prp3 was also performed in the presence of its DUB, Usp4Sart3. Ubiquitinated Prp3 was detected by autoradiography. The asterisk marks an N-terminally truncated Prp3 resulting from alternative start codon usage in the IVT/T reaction. (G) The Prp19 complex ubiquitinates the C-terminal domain of Prp3. 35S-Prp3 or truncation mutants (Prp3-N, Prp3-M, or Prp3-C) were tested for ubiquitination by affinity-purified Prp19 and UbcH5c. Ubiquitinated Prp3 was detected by autoradiography. Note that only Prp3-C, but neither Prp3-N nor Prp3-M, is ubiquitinated in a Prp19-dependent manner. The asterisk marks a truncation product of the Prp3-C construct.

The NTC has not yet been reconstituted from recombinant proteins. As this is similar to the E3 APC/C, we adapted a protocol established to study the ubiquitination of APC/C substrates to the NTC (Jin et al. 2008). We affinity-purified the NTC from HeLa extracts by using specific αPrp19 or αCdc5 antibodies (Fig. 4C, left panel). We allowed radiolabeled Prp3 to associate with the NTC, washed away unbound proteins, and then incubated the beads with ubiquitin, ATP, E1, and E2. Importantly, NTC purified with αPrp19 or αCdc5 antibodies efficiently catalyzed the ubiquitination of Prp3 (Fig. 4C, right panel). The NTC promoted the ubiquitination of Prp3 together with the E2 UbcH5c, but not with many other E2s (Supplemental Fig. 4E). The ubiquitination of Prp3 was competed away by an excess of recombinant HisPrp3, indicating that the NTC recognizes the correctly folded substrate (Supplemental Fig. 4F).

Only monoubiquitinated Prp3 was observed in the presence of methylubiquitin, demonstrating that the NTC decorates Prp3 with ubiquitin chains (Fig. 4D). Using single Lys ubiquitin mutants (ubi-K63), we found that the NTC is able to assemble K63-linked ubiquitin on Prp3 (Fig. 4E). The ubiquitin mutant ubi-I44A, which did not support splicing in yeast extracts (Bellare et al. 2008), was inactive in NTC-dependent chain formation (Fig. 4F). As expected from our binding studies, the NTC promoted the ubiquitination of the C-terminal domain of Prp3, while N-terminal or middle domains were not modified in a NTC-dependent manner (Fig. 4G). These results show that the NTC catalyzes Prp3 ubiquitination in vitro.

To determine whether the NTC modifies Prp3 in vivo, we analyzed the ubiquitination of Prp3 in HeLa cells in the presence of increased concentrations of Prp19. Overexpression of Prp19, which can oligomerize in vivo (Supplemental Fig. 4G; Ohi et al. 2005; Vander Kooi et al. 2006), likely recruits other NTC components to Prp3. Importantly, Prp3 ubiquitination was strongly increased upon coexpression of Prp19, as observed by Western blot or denaturing NiNTA purification (Fig. 5A,B). Prp19 also triggered the ubiquitination of endogenous Prp3 (Fig. 5C). As expected from our biochemical studies, Prp19 promoted the ubiquitination of the C-terminal domain of Prp3, whereas other Prp3 domains were not modified in a Prp19-dependent manner (Fig. 5D). Prp19 expression did not strongly affect the ubiquitination status of Lsm2, Prp4, Sart3, or Usp4 (Supplemental Fig. 4H). We also tested siRNAs to deplete Prp19 from HeLa cells, and found that efficient Prp19 knockdown resulted in premitotic arrest, as seen in earlier studies (Supplemental Fig. 4J). Importantly, the depletion of Prp19 using these siRNAs reduced the ubiquitination of Prp3 (Fig. 5E).

We next coexpressed Prp19 with ubiquitin mutants in which Lys residues commonly used for chain formation (K11, K48, and K63) were exchanged to arginine. The NTC failed to efficiently modify Prp3 upon expression of ubi-R63, as detected by Western blotting or denaturing NiNTA purification (Fig. 5F,G). This implied that, in vivo, the NTC decorates Prp3 with K63-linked chains, which usually do not trigger proteasomal degradation. Indeed, Prp19 did not reduce the cellular levels of Prp3 (Fig. 5A), and the proteasome inhibitor MG132 did not increase the abundance of unmodified or ubiquitinated Prp3 in the presence of Prp19 (Supplemental Fig. 4I). These findings suggest that the NTC decorates its substrate Prp3 with nonproteolytic K63-linked chains.

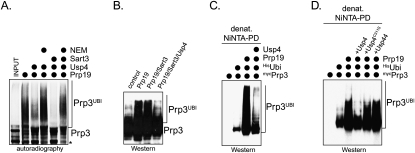

Because Usp4Sart3 efficiently disassembles K63-linked chains, it is reasonable to assume that it could oppose the NTC by deubiquitinating Prp3. To test this hypothesis, we used the NTC to ubiquitinate Prp3 in vitro, and then treated ubiquitinated Prp3 with Usp4, Usp4Sart3, or Usp4Sart3 inhibited by NEM. Indeed, Usp4 deubiquitinated Prp3, the efficiency of which was increased by Sart3 (Fig. 6A). To test whether Usp4 opposes the NTC in vivo, we analyzed the ubiquitination of Prp3 in HeLa cells expressing Prp19 and Usp4Sart3. Importantly, if Usp4Sart3 was coexpressed with Prp19, the NTC-dependent ubiquitination of Prp3 was eliminated (Fig. 6B,C). In contrast, the expression of inactive Usp4C311A or the unrelated DUB Usp44 did not affect Prp3 ubiquitination (Fig. 6D). These results show that the opposition between the NTC and Usp4Sart3 results in the reversible ubiquitination of a spliceosomal protein, Prp3.

Figure 6.

Usp4Sart3 counteracts the NTC. (A) Usp4Sart3 deubiquitinates Prp3 in vitro. 35S-Prp3 was ubiquitinated by affinity-purified NTC (Prp19), and was subsequently incubated with Usp4 or Usp4Sart3. Control reactions with NEM-inactivated Usp4 or Usp4Sart3 were performed in parallel. The ubiquitination of Prp3 was analyzed by autoradiography. The asterisk marks an N-terminally truncated Prp3 resulting from alternative start codon usage in the IVT/T reaction. (B) Usp4 counteracts Prp19 in vivo. mycPrp3 was expressed with Prp19, Sart3, and Usp4Sart3, as indicated, and was analyzed for modifications by αmyc-Western blot. (C) Usp4 counteracts the NTC in vivo, as detected by denaturing purification of ubiquitinated proteins. mycPrp3 was expressed with Hisubiquitin, Prp19, and Usp4Sart3, and covalently modified proteins were purified under denaturing conditions on NiNTA-agarose. Ubiquitinated mycPrp3 was detected by αmyc-Western blot. (D) Deubiquitination of Prp3 requires the catalytic activity of Usp4. mycPrp3 was coexpressed with Hisubiquitin, Prp19, and either Usp4Sart3, Usp4C311A/Sart3, or Usp44. Covalently modified proteins were purified on NiNTA-agarose under denaturing conditions, and ubiquitinated mycPrp3 was detected by αmyc-Western blotting.

Ubiquitin-dependent regulation of splicing

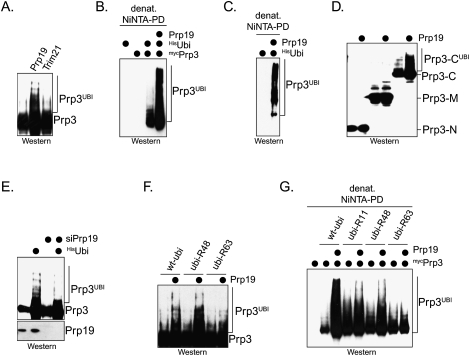

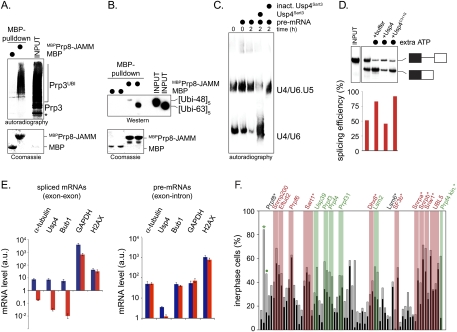

How does the ubiquitination of Prp3 regulate the spliceosome? To address this question, we searched for potential acceptors of ubiquitinated Prp3 within the U4, U5, and U6 snRNPs. Prp8, a component of the U5 snRNP, has been shown previously to bind ubiquitin through its variant JAMM domain in yeast (Bellare et al. 2006, 2008). Therefore, we considered the possibility that human Prp8 might function as a receptor for modified Prp3. Indeed, the JAMM domain of Prp8 associated efficiently with ubiquitinated Prp3, but not with the unmodified protein (Fig. 7A). Consistent with our earlier findings, Prp8 displayed a preference for binding K63-linked ubiquitin chains (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Ubiquitin-dependent regulation of the spliceosome. (A) The U5 component Prp8 recognizes ubiquitinated Prp3. 35S-Prp3 was ubiquitinated by the NTC and UbcH5c, and was incubated with immobilized MBP and MBPPrp8-JAMM (the isolated JAMM domain). Bound proteins were detected by autoradiography. The asterisk marks an N-terminally truncated Prp3 resulting from alternative start codon usage in the IVT/T reaction. (B) Prp8 preferentially interacts with K63-linked chains. MBP and MBPPrp8-JAMM were coupled to amylose resin and incubated with K48- or K63-linked ubiquitin pentamers, as indicated. Bound ubiquitin proteins were visualized by αubiquitin-Western blot. (C) Usp4Sart3 regulates the stability of the U4/U6.U5 snRNP in HeLa splicing extracts. HeLa splicing extracts were supplemented with Ftz-pre mRNA, Usp4Sart3, or NEM-treated, inactive Usp4Sart3, as indicated. The abundance of the U4/U6.U5 and U4/U6 snRNPs was monitored by Northern blotting using U6 snRNA as a probe (Konarska and Sharp 1987). (D) Usp4Sart3 regulates splicing in vitro. HeLa splicing extracts were prepared in the presence of ATP to maintain a functional ubiquitin system (Williamson et al. 2009). The splicing of radiolabeled Ftz-pre-mRNA was monitored by autoradiography in the presence of additional ATP, Usp4Sart3, or catalytically inactive Usp4C311S/Sart3, and gel bands were quantitated using ImageQuant software. The percent splicing efficiency was calculated as spliced mRNA over total mRNA (pre-mRNA + spliced mRNA). (E) Usp4 is required for splicing in cells. HeLa cells were treated with siRNA against Usp4, and were arrested in mitosis with nocodazole. The abundance of mature mRNAs against the indicated targets was determined by qPCR. (Blue bars) Control cells; (red bars) Usp4-depleted cells; (a.u.) arbitrary units derived from the cT-value. Primers annealed to either exon junction sequences or the single exon of H2AX. In a control qPCR experiment, primers annealed to the one of the gene's exons and neighboring introns. (F) Loss of several spliceosomal proteins results in cell cycle defects also observed upon Usp4 depletion. Spliceosomal proteins were depleted from HeLa cells by siRNA. HeLa cells were treated with taxol, and the percentage of cells showing premitotic arrest or spindle checkpoint bypass was determined. Positive hits are indicated above, and those marked with an asterisk were identified previously in siRNA screens. Depletions resulting predominantly in premitotic arrest are labeled in red, and those with a significant spindle checkpoint bypass phenotype are marked in green.

These observations suggested that ubiquitination of the U4 protein Prp3, and its recognition by the U5 component Prp8, could stabilize interactions within the U4/U6.U5 snRNP. If this were the case, then increasing the activity of Usp4Sart3 might interfere with the integrity of the U4.U6/U5 snRNP by promoting the deubiquitination of Prp3. To test this hypothesis, we used Northern blotting (Konarska and Sharp 1987) to monitor the composition of U6-containing snRNPs in HeLa splicing extracts treated with recombinant Usp4Sart3. Strikingly, addition of active, but not inactive, Usp4Sart3 disrupted U4/U6.U5 snRNPs and led to an accumulation of U4/U6 snRNPs (Fig. 7C). We next tested whether the destabilization of U4/U6.U5 snRNPs disrupts the splicing of pre-mRNA substrates. To retain a functional ubiquitin system, HeLa extracts were prepared in the presence of ATP, which led to some basal splicing activity; however, addition of more ATP strongly promoted splicing under these conditions (Fig. 7D). Importantly, when extracts were also supplemented with active, but not inactive, Usp4Sart3, splicing of Ftz pre-mRNA was inhibited (Fig. 7D). Overall, these findings strongly suggest that Usp4Sart3 is able to regulate the spliceosome by controlling the stability of the U4/U6.U5 snRNP.

We next investigated whether Usp4 is required for proper spliceosome activity in cells by measuring levels of mature spliced mRNAs. We siRNA-depleted Usp4 from both asynchronous and mitotic HeLa cells and examined the fidelity of mRNA splicing for intron-containing genes by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using primers spanning exon junctions. As a control, we monitored the levels of unspliced mRNAs by using primer pairs annealing to an exon and its neighboring intron, and we determined the abundance of an intronless mRNA, histone H2AX, by using primers annealing to its single exon. Importantly, the loss of Usp4 led to a strong reduction in the abundance of spliced mRNAs, which was most dramatically observed in mitotic cells (Fig. 7E; Supplemental Fig. 5). The mRNAs encoding the spindle constituent α-tubulin and Bub1, a spindle checkpoint component, appeared particularly sensitive to Usp4 depletion. In contrast, the levels of unspliced α-tubulin or Bub1 mRNA, or that of H2AX mRNA, was not affected by loss of Usp4. Thus, Usp4 is required to ensure the fidelity of splicing, at least for a subset of mRNAs in cells.

If Usp4 function is required for splicing of spindle constituents or spindle checkpoint components, then it is reasonable to assume that depletion of other splicing factors should result in similar cell cycle defects as does loss of Usp4. It was described previously that inhibition of the spliceosome can lead to cell cycle arrest, and, indeed, depletion of Sart1, Dhx8, Lsm6, Snrpa, Snrpb, Snwi, or UBL5 delayed cell cycle progression (Fig. 7F; Kittler et al. 2004, 2007). Importantly, the loss of Prp4, Prp4B kinase, Prp31, Usp39, and Lsm2, all of which are components of the U4/U6.U5 snRNP, not only delayed cell division, but also caused significant spindle checkpoint bypass, very similar to what we observed with Usp4 depletion (Fig. 7F; Montembault et al. 2007; van Leuken et al. 2008). These severe cell cycle defects underscore the importance of the ubiquitin-dependent regulation of the spliceosome for cellular control.

Discussion

Here, we identify an important role for reversible ubiquitination in the regulation of the spliceosome. We show that the spliceosomal NTC promotes the modification of the U4 component Prp3 with K63-linked ubiquitin chains. The ubiquitinated Prp3 can be recognized by the U5 component Prp8, which allows for the stabilization of the U4/U6.U5 snRNP. Prp3 is deubiquitinated again by Usp4Sart3, which likely facilitates the ejection of Prp3 from the spliceosome during maturation of its active site. Underscoring the importance of reversible ubiquitination for cellular control, this modification pathway is required for efficient splicing, accurate cell cycle progression, and sensitivity to the chemotherapeutic taxol in cells.

Ubiquitin-dependent regulation of splicing

Ubiquitination is an attractive mechanism to help guide the structural rearrangements in the spliceosome. As K63-linked ubiquitin chains often alter protein interactions, their attachment or removal from splicing factors could trigger the changes in the composition of the spliceosome, as observed at several stages of the splicing reaction (Wahl et al. 2009). The interactions between RNAs and proteins within the spliceosome are of weak affinity, suggesting that ubiquitination could contribute significantly to complex formation. Moreover, the recycling of spliceosomal proteins after a completed round of splicing requires that any modification is reversible, which could be achieved by DUBs. Indeed, it has been shown that the spliceosome is regulated by ubiquitination (Ohi et al. 2003; Bellare et al. 2008), but substrates or enzymes of these reactions have not yet been characterized.

Here, we identify the first substrate of the spliceosomal Prp19 complex (NTC) and the first spliceosomal DUB, Usp4Sart3, which allows us to propose a mechanism for the ubiquitin-dependent regulation of splicing (Fig. 8). Together with observations by other laboratories (Ohi et al. 2003; Bellare et al. 2006, 2008; Chen et al. 2006), our data suggest that ubiquitination regulates the stability of the U4/U6.U5 snRNP, which undergoes major changes in its state (free or spliceosome-bound) and composition (U4/U6.U5 vs. free U4 vs. U4/U6). The NTC decorates Prp3, a key component of the U4 snRNP, with K63-linked ubiquitin chains. The ubiquitinated Prp3 is recognized by the variant JAMM domain in the U5 protein Prp8, which preferentially interacts with K63-linked chains. The ubiquitin-dependent interaction between the U4 component Prp3 and the U5 protein Prp8 thus stabilizes the U4/U6.U5 snRNP.

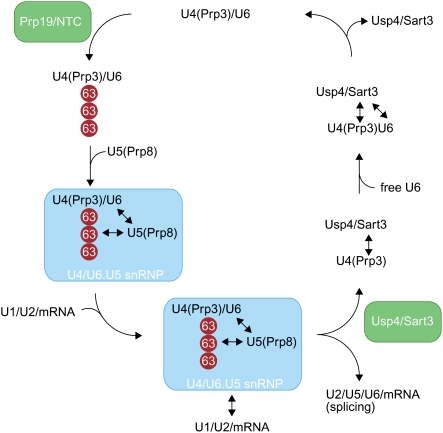

Figure 8.

Model of the ubiquitin-dependent regulation of the U4/U6.U5 snRNP. The Prp19 complex (NTC) promotes the modification of Prp3, a U4 component, with K63-linked ubiquitin chains (red circles). Ubiquitinated Prp3 can be recognized by the JAMM domain of Prp8, a U5 component, thereby allowing for the stabilization of the U4/U6.U5 snRNP. After docking of the U4/U6.U5 snRNP at the spliceosome, U4 snRNA and the U4 proteins dissociate along with U1 snRNA and proteins of the U6 snRNP. We propose that deubiquitination of Prp3 by Usp4Sart3 decreases its affinity to Prp8 and facilitates dissociation. Sart3 also promotes the reannealing of U4 and U6 snRNPs, allowing the U4/U6 snRNP to enter another round of splicing.

Once the U4/U6.U5 snRNP has been recruited to the spliceosome, structural rearrangements result in the release of Prp3 and other U4 proteins, as well as the U1 and U4 snRNA (Wahl et al. 2009). This reorganization is required for the U6 snRNA to participate in the formation of the active site of the spliceosome. The deubiquitination of Prp3 by Usp4Sart3 weakens the interaction of Prp3 with the U5 component Prp8 to facilitate the U4 snRNP dissociation from the spliceosome. Indeed, we found that incubation of HeLa extracts with Usp4Sart3 could trigger the disassembly of the U4/U6.U5 snRNP. Interestingly, Sart3 not only acts as a substrate targeting factor of Usp4, but also promotes the reassembly of the U4/U6 snRNP (Bell et al. 2002; Trede et al. 2007). In this manner, Sart3 could effectively couple the deubiquitination of Prp3 and its ejection from the spliceosome with its recycling into U4/U6 snRNPs. We envision that a newly formed U4/U6 snRNP will recruit the NTC to trigger another round of splicing for the U4/U6.U5 snRNP. Our model therefore suggests that the reversible ubiquitination of Prp3 is able to modulate interactions between distinct snRNP complexes during the catalytic cycle of the spliceosome.

By identifying its first substrate, we demonstrate that the NTC is a bona fide E3. In yeast, mutation of Prp19 destabilizes the U4 and U6 snRNPs, which may result from the inefficient ubiquitination of Prp3 or, potentially, other substrates (Lygerou et al. 1999; Chen et al. 2006). The NTC is known to regulate steps after the dissociation of the U4 snRNP and Prp3, such as the stabilization of the interaction between the U6 snRNA and the spliceosome (Chan et al. 2003). Thus, it is likely that the NTC ubiquitinates proteins in addition to Prp3, which may be controlled by DUBs other than Usp4.

Splicing and disease

We identified Usp4 in a screen for cell cycle regulators, as depletion of Usp4 interfered with the ability of cells to respond to treatment with the chemotherapeutic taxol. Very similar cell cycle phenotypes were observed upon loss of the spliceosomal recycling factor Sart3, the U4 component Prp3, and several other U4/U6.U5 snRNP components, including Prp4B and Usp39 (Fig. 7E; Montembault et al. 2007; van Leuken et al. 2008). Accordingly, Usp4 was found recently to associate with Sart3 and other splicing factors in a proteomic interaction study on human DUBs (Sowa et al. 2009). We conclude that aberrant splicing is the most likely cause of the cell cycle defects observed in Usp4-depleted cells.

It is unlikely that the cell cycle defects caused by loss of Usp4 result from the aberrant splicing of a single mRNA. A recent study of a mouse model with impaired spliceosomal function showed that the mRNA levels of multiple cell cycle regulators—including Bub1, Brca1, Cdc25B, HURP, Tpx2, or Aurora B—were reduced (Zhang et al. 2008). Moreover, depletion of spliceosomal proteins in human cells by siRNA or mutation of their genes in yeast reduces mRNA levels of multiple cell cycle regulators (Burns et al. 2002; Pacheco et al. 2006; Xiao et al. 2007). In addition, we found that the abundance of mature α-tubulin and Bub1 mRNAs was strongly reduced upon depletion of Usp4. We propose that loss of Usp4 results in the depletion of several cell cycle regulators with pleiotropic effects on the cell cycle or spindle checkpoint.

Both an aberrant spindle structure and weakened spindle checkpoint increase the frequency of chromosome missegregation, which could result in aneuploidy and contribute to tumorigenesis (Weaver and Cleveland 2009). Accordingly, the USP4 gene localizes to a chromosomal region deleted in SCLC, and expression levels of Usp4 are diminished in SCLC cells, suggesting that Usp4 may act as a tumor suppressor (Frederick et al. 1998). High levels of aneuploidy are characteristic of SCLCs, which often develop resistance to chemotherapy, including treatment with taxol (Hann and Rudin 2007). Conversely, Prp19 is overexpressed in lung cancer (Confalonieri et al. 2009), and changes in the expression levels of splicing factors or alterations in cis-acting mRNA elements regulating splicing have been associated with tumorigenesis (TA Cooper et al. 2009). It is a tempting hypothesis that aberrant splicing results in inaccurate sister chromatid segregation, thereby leading to tumorigenesis.

It is also interesting to note that both the Usp4 substrate Prp3 and its acceptor, Prp8, are mutated in a familial form of retinitis pigmentosa (for review, see TA Cooper et al. 2009). The same disease can result from mutations that impair the structure or function of the primary cilium (Marshall 2008). Similar to the spindle, the primary cilium consists of microtubules and depends on the correct splicing of α-tubulin. Thus, the misregulation of the spliceosome, as caused by loss of Usp4 or mutation of Prp3, and the resulting aberrant splicing of α-tubulin, might lead to multiple diseases, which will be investigated in more detail in the future.

Materials and methods

siRNA screening

The focused siRNA screens against DUBs and spliceosomal proteins were performed as described (Stegmeier et al. 2007). siRNA sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 1.. HeLa cells were seeded in 96-well plates (5000 cells per well) and transfected with siRNAs using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen). After 48 h, cells were treated with 100 nM taxol. After 24 h, cells were stained with Hoechst and fixed with 4% formaldehyde. Images were taken on an ImageXpressmicro (Molecular Devices), and mitotic or interphase cells were counted. Interphase cells with a single nucleus (indicative of premitotic arrest) and those with multiple nuclei or with multilobed nuclei (indicative of spindle checkpoint bypass) were recorded independently.

Plasmids and antibodies

The coding sequence for human Usp4, Sart3, Prp3, and Prp19 was cloned into pCS2, pCS2-myc, and pCS2-HA for expression in human cells; pFB for purification from Sf9 cells; and pMAL and pET28 for expression in bacteria, using FseI/AscI restriction enzymes. The Usp4C311A mutant was generated by site-directed mutagenesis. Sart3ΔHAT4–6 (Δ324–430), Sart3ΔHAT7 (Δ487–520), and Sart3Δcoiled-coil (Δ559–619) were cloned into pCS2-HA for IVT/T and immunoprecipitation. Deletion mutants of Usp4, Sart3, and Prp3 were generated by PCR and cloned into the same vectors as described. Ubiquitin and various mutants were cloned into pCS2 for expression in human cells (Jin et al. 2008). pBSU6a, which encodes human U6 snRNA, was a kind gift from Magda Konarska (Rockefeller University). Antibodies were purchased for detection of Usp4, Prp3, CDC5, and Prp19 (Bethyl Laboratories); Flag (Sigma); myc and HA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); tubulin (Calbiochem); and β-actin (Abcam).

Recombinant proteins

MBPUsp4, MBPUsp4-NT (amino acids 1–296), MBPSart3, and MBPPrp3 were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3/RIL). Bacteria were lysed in LBM buffer (20 mM Tris at pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, 0.2 mg/mL lysozyme). The cleared lysate was incubated with amylose beads. After washing, proteins were eluted in EB buffer (20 mM Tris at pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM maltose, 1 mM DTT) and dialyzed into PBS and 2 mM DTT. For purification of HisSart3 and HisPrp3, E. coli BL21 (DE3/RIL) were transformed with the pET28 construct. Bacteria were lysed in LBH buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate at pH 8, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 0.1% Tween 20, 0.2 mg/mL lysozyme), and the cleared supernatant was bound to NiNTA-agarose (Qiagen). Beads were washed, and HisSart3 or HisPrp3 were eluted in EBH buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate at pH 8, 500 mM NaCl, 200 mM imidazole) and dialyzed into PBS and 2 mM DTT. HisUsp4 and HisSart3 were also purified from baculovirus-infected insect cells on NiNTA-agarose (Qiagen) as described above. HisE1, His-tagged E2 proteins, Hisubiquitin, and ubiquitin mutants were prepared as described (Jin et al. 2008). Recombinant ubiquitin and ubiquitin mutants were obtained from Boston Biochem.

Identification of Usp4-binding partners

MBP and MBPUsp4-NT were coupled to amylose beads and incubated with extracts of mitotic HeLa S3 cells with rocking for 3 h at 4°C. Amylose beads were washed five times with 1 mL of immunoprecipitation buffer (25 mM HEPES at pH 7.5, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM KCl, 150 mM NaCl) containing 0.1% Tween 20, and then were washed once with 1 mL of immunoprecipitation buffer without Tween. Beads were eluted in SDS buffer, and binding reactions were analyzed by Coomassie staining. Proteins specifically retained by the MBPUsp4-NT were excised, in-gel-digested with trypsin, and analyzed by mass spectrometry at the HHMI mass spectrometry facility.

MBP pull-down of 35S-labeled substrates

MBP and MBP-tagged proteins were coupled to amylose beads, and were incubated with in vitro transcribed and translated 35S substrates for 3 h at 4°C. Beads were washed and eluted in SDS–gel buffer. Samples were resolved by Coomassie staining of SDS-PAGE gels, as well as by autoradiography.

Immunoprecipitation

HeLa cells were collected and lysed in immuoprecipitation buffer (50 mM HEPES at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM KCl, 0.1% Tween 20, 2 mM DTT, protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche]). Precleared lysates were incubated with rabbit IgG, primary antibody, myc-agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Flag-agarose (Sigma), or HA-matrix (Roche) for 4 h at 4°C. When required, protein G-agarose (Roche) was added for 60 min. Beads were washed and eluted in SDS–gel buffer. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot.

In vitro ubiquitination

For approximately five ubiquitination reactions, human Prp19 and associated proteins were affinity-purified from 1-mL extracts of mitotic HeLa S3 cells by using 20 μL of the specific αPrp19 or CDC5 antibody (Bethyl) and 80 μL of protein G-agarose (Roche). Washed beads were incubated for 30 min at 30°C under constant shaking with 50 nM human E1, 100 nM E2, 1 mg/mL ubiquitin, energy mix (20 mM ATP, 15 mM creatine phosphate, creatine phosphokinase), 1 mM DTT, and 35S-Prp3 synthesized by IVT/T (Promega). Reactions were analyzed by SDS–gel electrophoresis and autoradiography.

His-ubiquitin pull-down assay

HeLa cells were transfected with pCS2-tagged constructs as indicated. Nocodazole was added to cells 24 h after transfection to a concentration of 100 ng/mL. Twenty-four hours after nocodazole treatment, cells were resuspended in Buffer A (6 M guanidine-HCl, 0.1 M Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4, 10 mM imidazole at pH 8.0) and sonicated. Cell lysates were added to 50 μL of equilibrated Ni-NTA agarose and were allowed to incubate for 3 h at room temperature. Beads were then washed one time with Buffer A, followed by two washes with Buffer A/TI (1 vol of Buffer A, 3 vol of Buffer TI [25 mM Tris-Cl, 20 mM imidazole at pH 6.8]), and one wash with Buffer TI; all washes were 1 mL. The protein conjugates were eluted in 50 mL of 2× laemmli/imidazole (200 mM imidazole) and boiled. Eluates were analyzed by Western blotting.

Deubiquitination assays

The DUB activity of Usp4 was tested using recombinant Lys48- and Lys63-linked chains (Boston Biochem). Both pentaubiquitin chains and chains of mixed length containing three to seven ubiquitin molecules were assayed. The reactions were incubated in DUB buffer (25 mM Tris/HCl at pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 15 mM creatine phosphate, 2 mM ATP) for 1 h at 30°C. Recombinant Usp4, Sart3, Usp4Sart3, or NEM-inactivated Usp4Sart3 was added as indicated. Reactions were stopped by boiling for 5 min, and were analyzed by Western blot against ubiquitin. Alternatively, ubiquitin-AMC (Boston Biochem) was incubated in DUB buffer with recombinant Usp4, Sart3, Usp4Sart3, or NEM-inactivated Usp4Sart3, and deubiquitination was analyzed in a spectrophotometer using the increase in fluorescence at 469 nm observed upon release of AMC.

To measure the activity of Usp4 toward Prp3, 35S-labeled Prp3 was ubiquitinated with Prp19 for 30 min at 30°C. Usp4 or Usp4Sart3 in DUB buffer (25 mM Tris/HCl at pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 15 mM creatine phosphate, 2 mM ATP) was added for 1 h at 23°C. As a control, Usp4Sart3 was inactivated with NEM before being added to the reaction. These reactions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

Immunofluorescence analysis

HeLa cells were grown to 80% confluence on glass coverslips. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde, and were incubated with αHA or αMyc antibody, followed by secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody coupled to Alexa488 (Molecular Probes). Tubulin was stained with Cy3–α-tubulin antibody (Sigma), and DNA was detected with DAPI (Sigma). Cells were visualized using 60× magnification on an Olympus IX71 microscope, and pictures were analyzed using ImageJ.

In vitro splicing assays

Splicing reactions were performed in HeLa cell nuclear extract in a volume of 25 μL. The splicing reactions included 7 μL of HeLa extract, 12% glycerol, 12 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 4 mM MgCl2, 0.3 mM DTT, 10 U of RNasin, 60 mM KCl, 2% PEG, 3 mM ATP, 5 mM creatine phosphate, and 25 fmol/μL 32P-labeled Ftz pre-mRNA substrate, and were incubated for 2 h at 30°C. Extract was preincubated with either 5 μL of Buffer D (20 mM HEPES at pH 7.9, 20% glycerol, 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA) or Usp4Sart3 (10 μM final concentration) for 15 min at 30°C before the addition of splicing buffer and pre-mRNA. Splicing products were subject to proteinase K treatment for 30 min at 37°C. After phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, splicing products were resuspended in formamide dyes, and one-third of the reaction was resolved on a 12% polyacrylamide urea denaturing gel and analyzed by autoradiography.

Native gels and Northern blotting

Splicing reactions (10 μL) were performed as above, with the modification of using 0.18 pmol of cold Ftz as a pre-mRNA substrate. Reactions were terminated with heparin (5 mg/mL final concentration) for 10 min at 30°C, samples were resolved on a 4% tris-glycine (pH 8.8) native gel for 5 h at 4°C, and the RNA was transferred to nylon membrane using a Tris-Acetate-EDTA (TAE, pH 7.8) buffering system as described previously (Konarska 1989). The membrane was then air-dried, UV-cross-linked, and prehybridized for 4 h with Hybridization Buffer (50% formamide, 0.1% Denhardt's solution, 5× SSC, 50 mM sodium phosphate at pH 6.5, 1% SDS, 2.5% dextran sulfate, 0.1 mg/mL salmon sperm DNA) at 42°C. Hybridization was carried out for at least 16 h at 42°C in 15 mL of the same buffer containing 2 × 105 cpm/mL labeled U6 RNA probe. U6-specific RNA probe was transcribed with T3 RNA polymerase from EcoRI-cleaved plasmid pBSU6a as described previously (Konarska and Sharp 1987). The membrane was washed three times for 30 min with 0.5× SSC and 0.1% SDS at room temperature, and was analyzed by autoradiography.

qPCR analysis

RNA was isolated from both asynchronous and nocodozole-arrested HeLa cells in the presence or absence of Usp4 siRNA knockdown (oligofectamine reverse transfection). cDNA was synthesized using the Fermentas First Strand cDNA synthesis kit. qPCR reactions were carried out using 2× SYBR Green/Rox Master Mix (Fermentas), 100 nM primers, and 75 ng of RNA, and were analyzed using a Stratagene MX3000 thermocycler. All reactions were carried out with –RT control and in triplicate. Primers were designed so as to span exon junctions, with the exception of H2AX, which does not possess introns. Primer sequences are as follows: α-tubulin-F, CCGCCTAAGAGTCGCGCTG; α-tubulin-R, GCACTCACGCATGGTTGCTG; Usp4-F, ACCTTGCAGTCAAATGGATCTGG; Usp4-R, TCCAAGTCCACAGAGCCCAGG; Bub1-F, AAAGGTCCGAGGTTAATCCA; Bub1-R, AGGAGGAACAACAGGAGGTG; GAPDH-F, GGCTGGGGCTCATTTGCAGG; GAPDH-R, CCCATGACGAACATGGGGGC; H2AX-F, AAGGTGAGTGAGGCCCTCGG; and H2AX-R, GGCCGCGTCTGAAAGTCCTG. In a control qPCR experiment, primers were designed to anneal to an exon and neighboring intron, using the following sequences: α-tubulin-F(Ex), CTGGAACACGGCATCCAGCC; α-tubulin-R(In), GCCAATGGTGTAGTGCCCTCG; Usp4-F(Ex), TGTGGTCTGGAAGGGACGCC; Usp4-R(In), GCCGCCCATTGGCATCCTTC; Bub1-F(Ex), GGCAGAGTTGGGCGTTGAGG; Bub1-R(In), AGTCTTGGGCTTGATGGCTGGA; GAPDH-F(Ex), ACCCCTGGCCAAGGTCATCC; GAPDH-R(In), GACACGGAAGGCCATGCCAG.

Acknowledgments

We thank Madga Konarska for sharing plasmids. We are very grateful to Julia Schaletzky for many inspiring discussions, and for carefully reading the manuscript. We thank Sharleen Zhou (University of California at Berkeley) for performing mass spectrometry experiments, and Andreas Martin for providing help with the fluorescence analysis of Usp4 activity. This work is supported by a grant from the NIH to S.J.E., GM054137 to J.W.H., AG011085 to J.W.H. and S.J.E., GM61987 to D.R., GM39023 to M.W.K., and GM083064 and a March of Dimes Grant to M.R. E.J.S. was supported by the Korea Research Foundation Grant (KRF-2007-033-E0002). S.J..E is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator, and M.R. is a Pew Scholar.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1925010.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

References

- Aravind L, Koonin EV 2000. The U box is a modified RING finger—A common domain in ubiquitination. Curr Biol 10: R132–R134 doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00398-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell M, Schreiner S, Damianov A, Reddy R, Bindereif A 2002. p110, a novel human U6 snRNP protein and U4/U6 snRNP recycling factor. EMBO J 21: 2724–2735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellare P, Kutach AK, Rines AK, Guthrie C, Sontheimer EJ 2006. Ubiquitin binding by a variant Jab1/MPN domain in the essential pre-mRNA splicing factor Prp8p. RNA 12: 292–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellare P, Small EC, Huang X, Wohlschlegel JA, Staley JP, Sontheimer EJ 2008. A role for ubiquitin in the spliceosome assembly pathway. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15: 444–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns CG, Ohi R, Mehta S, O'Toole ET, Winey M, Clark TA, Sugnet CW, Ares M Jr, Gould KL 2002. Removal of a single α-tubulin gene intron suppresses cell cycle arrest phenotypes of splicing factor mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 22: 801–815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SP, Kao DI, Tsai WY, Cheng SC 2003. The Prp19p-associated complex in spliceosome activation. Science 302: 279–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZJ, Sun LJ 2009. Nonproteolytic functions of ubiquitin in cell signaling. Mol Cell 33: 275–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Kao DI, Chan SP, Kao TC, Lin JY, Cheng SC 2006. Functional links between the Prp19-associated complex, U4/U6 biogenesis, and spliceosome recycling. RNA 12: 765–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn MA, Kowal P, Yang K, Haas W, Huang TT, Gygi SP, D'Andrea AD 2007. A UAF1-containing multisubunit protein complex regulates the Fanconi anemia pathway. Mol Cell 28: 786–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Confalonieri S, Quarto M, Goisis G, Nuciforo P, Donzelli M, Jodice G, Pelosi G, Viale G, Pece S, Di Fiore PP 2009. Alterations of ubiquitin ligases in human cancer and their association with the natural history of the tumor. Oncogene 28: 2959–2968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper EM, Cutcliffe C, Kristiansen TZ, Pandey A, Pickart CM, Cohen RE 2009. K63-specific deubiquitination by two JAMM/MPN+ complexes: BRISC-associated Brcc36 and proteasomal Poh1. EMBO J 28: 621–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper TA, Wan L, Dreyfuss G 2009. RNA and disease. Cell 136: 777–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois G, Gilmore TD 2006. Mutations in the NF-κB signaling pathway: Implications for human disease. Oncogene 25: 6831–6843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshaies RJ, Joazeiro CA 2009. RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu Rev Biochem 78: 399–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick A, Rolfe M, Chiu MI 1998. The human UNP locus at 3p21.31 encodes two tissue-selective, cytoplasmic isoforms with deubiquitinating activity that have reduced expression in small cell lung carcinoma cell lines. Oncogene 16: 153–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabbe C, Dikic I 2009. Functional roles of ubiquitin-like domain (ULD) and ubiquitin-binding domain (UBD) containing proteins. Chem Rev 109: 1481–1494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann CL, Rudin CM 2007. Fast, hungry and unstable: Finding the Achilles' heel of small-cell lung cancer. Trends Mol Med 13: 150–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L, Williamson A, Banerjee S, Philipp I, Rape M 2008. Mechanism of ubiquitin-chain formation by the human anaphase-promoting complex. Cell 133: 653–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurica MS, Moore MJ 2003. Pre-mRNA splicing: Awash in a sea of proteins. Mol Cell 12: 5–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerscher O, Felberbaum R, Hochstrasser M 2006. Modification of proteins by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 22: 159–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittler R, Putz G, Pelletier L, Poser I, Heninger AK, Drechsel D, Fischer S, Konstantinova I, Habermann B, Grabner H, et al. 2004. An endoribonuclease-prepared siRNA screen in human cells identifies genes essential for cell division. Nature 432: 1036–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittler R, Surendranath V, Heninger AK, Slabicki M, Theis M, Putz G, Franke K, Caldarelli A, Grabner H, Kozak K, et al. 2007. Genome-wide resources of endoribonuclease-prepared short interfering RNAs for specific loss-of-function studies. Nat Methods 4: 337–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegl M, Hoppe T, Schlenker S, Ulrich HD, Mayer TU, Jentsch S 1999. A novel ubiquitination factor, E4, is involved in multiubiquitin chain assembly. Cell 96: 635–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komander D, Lord CJ, Scheel H, Swift S, Hofmann K, Ashworth A, Barford D 2008. The structure of the CYLD USP domain explains its specificity for Lys63-linked polyubiquitin and reveals a B box module. Mol Cell 29: 451–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konarska MM 1989. Analysis of splicing complexes and small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles by native gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol 180: 442–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konarska MM, Sharp PA 1987. Interactions between small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles in formation of spliceosomes. Cell 49: 763–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lygerou Z, Christophides G, Séraphin B 1999. A novel genetic screen for snRNP assembly factors in yeast identifies a conserved protein, Sad1p, also required for pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell Biol 19: 2008–2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeder C, Guthrie C 2008. Modifications target spliceosome dynamics. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15: 426–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WF 2008. The cell biological basis of ciliary disease. J Cell Biol 180: 17–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medenbach J, Schreiner S, Liu S, Lührmann R, Bindereif A 2004. Human U4/U6 snRNP recycling factor p110: Mutational analysis reveals the function of the tetratricopeptide repeat domain in recycling. Mol Cell Biol 24: 7392–7401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montembault E, Dutertre S, Prigent C, Giet R 2007. PRP4 is a spindle assembly checkpoint protein required for MPS1, MAD1, and MAD2 localization to the kinetochores. J Cell Biol 179: 601–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijman SM, Luna-Vargas MP, Velds A, Brummelkamp TR, Dirac AM, Sixma TK, Bernards R 2005. A genomic and functional inventory of deubiquitinating enzymes. Cell 123: 773–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nottrott S, Urlaub H, Lührmann R 2002. Hierarchical, clustered protein interactions with U4/U6 snRNA: A biochemical role for U4/U6 proteins. EMBO J 21: 5527–5538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohi MD, Vander Kooi CW, Rosenberg JA, Chazin WJ, Gould KL 2003. Structural insights into the U-box, a domain associated with multi-ubiquitination. Nat Struct Biol 10: 250–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohi MD, Vander Kooi CW, Rosenberg JA, Ren L, Hirsch JP, Chazin WJ, Walz T, Gould KL 2005. Structural and functional analysis of essential pre-mRNA splicing factor Prp19p. Mol Cell Biol 25: 451–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco TR, Moita LF, Gomes AQ, Hacohen N, Carmo-Fonseca M 2006. RNA interference knockdown of hU2AF35 impairs cell cycle progression and modulates alternative splicing of Cdc25 transcripts. Mol Biol Cell 17: 4187–4199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson C 2002. A new gun in town: The U box is a ubiquitin ligase domain. Sci STKE 2002:pe4 doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.116.pe4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Turcu FE, Ventii KH, Wilkinson KD 2009. Regulation and cellular roles of ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinating enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem 78: 363–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Yoshikawa A, Yamagata A, Mimura H, Yamashita M, Ookata K, Nureki O, Iwai K, Komada M, Fukai S 2008. Structural basis for specific cleavage of Lys 63-linked polyubiquitin chains. Nature 455: 358–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seet BT, Dikic I, Zhou MM, Pawson T 2006. Reading protein modifications with interaction domains. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 473–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Rape M 2007. Reverse the curse—The role of deubiquitination in cell cycle control. Curr Opin Cell Biol 20: 156–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowa ME, Bennett EJ, Gygi SP, Harper JW 2009. Defining the human deubiquitinating enzyme interaction landscape. Cell 138: 389–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanĕk D, Rader SD, Klingauf M, Neugebauer KM 2003. Targeting of U4/U6 small nuclear RNP assembly factor SART3/p110 to Cajal bodies. J Cell Biol 160: 505–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegmeier F, Rape M, Draviam VM, Nalepa G, Sowa ME, Ang XL, McDonald ER III, Li MZ, Hannon GJ, Sorger PK, et al. 2007. Anaphase initiation is regulated by antagonistic ubiquitination and deubiquitination activities. Nature 446: 876–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trede NS, Medenbach J, Damianov A, Hung LH, Weber GJ, Paw BH, Zhou Y, Hersey C, Zapata A, Keefe M, et al. 2007. Network of coregulated spliceosome components revealed by zebrafish mutant in recycling factor p110. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 6608–6613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Kooi CW, Ohi MD, Rosenberg JA, Oldham ML, Newcomer ME, Gould KL, Chazin WJ 2006. The Prp19 U-box crystal structure suggests a common dimeric architecture for a class of oligomeric E3 ubiquitin ligases. Biochemistry 45: 121–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leuken RJ, Luna-Vargas MP, Sixma TK, Wolthuis RM, Medema RH 2008. Usp39 is essential for mitotic spindle checkpoint integrity and controls mRNA-levels of aurora B. Cell Cycle 7: 2710–2719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada K, Tanji K, Kamitani T 2006. Oncogenic protein UnpEL/Usp4 deubiquitinates Ro52 by its isopeptidase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 339: 731–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl MC, Will CL, Luhrmann R 2009. The spliceosome: Design principles of a dynamic RNP machine. Cell 136: 701–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver BA, Cleveland DW 2009. The role of aneuploidy in promoting and suppressing tumors. J Cell Biol 185: 935–937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson A, Wickliffe KE, Mellone BG, Song L, Karpen GH, Rape M 2009. Identification of a physiological E2 module for the human anaphase-promoting complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 18213–18218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J, Fang G 2006. HURP controls spindle dynamics to promote proper interkinetochore tension and efficient kinetochore capture. J Cell Biol 173: 879–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao R, Sun Y, Ding JH, Lin S, Rose DW, Rosenfeld MG, Fu XD, Li X 2007. Splicing regulator SC35 is essential for genomic stability and cell proliferation during mammalian organogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 27: 5393–5402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, Rape M 2009. Building ubiquitin chains: E2 enzymes at work. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 755–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Lotti F, Dittmar K, Younis I, Wan L, Kasim M, Dreyfuss G 2008. SMN deficiency causes tissue-specific perturbations in the repertoire of snRNAs and widespread defects in splicing. Cell 133: 585–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]